Abstract

Previous research on the platformization of news has mostly been devoted to considering the effects of social media on the news industry. The current study focuses on Taboola and Outbrain, two leading content recommendation platforms. The companies form “partnerships” with news organizations, through which they take over a designated space on news websites and curate news, sponsored content, and advertisements, creating a blend that—the companies claim—maximizes monetization. We argue that the unique business model and distribution mechanism of these companies has a distinct effect on news sites, their audiences, and ultimately the journalism profession. An empirical analysis of 97,499 recommended content items, scraped from nine Israeli news sites, suggests that the spaces created by these partnerships blur the distinction between editorial and monetization logics. In addition, we find the creation of indirect network effects: while large media groups benefit from the circulation of sponsored content across their websites, smaller publishers pay Taboola and Outbrain as advertisers to drive traffic to their websites. Thus, even though these companies discursively position themselves as "gallants of the open web"—freeing publishers from the grip of walled-garden platforms—they de facto expose the news industry to the influence of the platform economy.

Introduction

We are the Robin Hood of the open and free Internet against the giants of Google, Facebook and Amazon.

Adam Singolda, Taboola’s CEO and founder. (Habib-Valdhorn Citation2021)

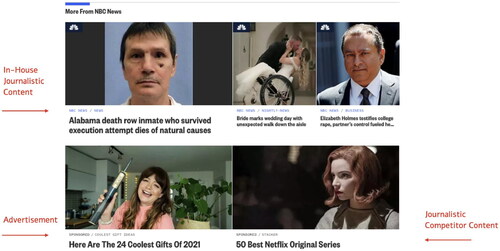

On Oct 5, 2021 an article describing the losses of one of Israel’s largest investment firms, AS Investments, was published on a leading financial news site themarker.com. The very next day, directly beneath the article and under the header: “From around the Web,” another article appeared, glorifying AS Investments’ consumer service. What might have looked to the average reader as a link to a related but positive article, published by the same news site that they were browsing (The Marker), was actually news content originally published three months earlier by The Marker’s rival, Globes—and repurposed and redistributed as an advertisement.

The transformation of news to ads, together with the blurring of the boundaries between different types of content, and between news brands, was made possible due to the services provided by content recommendation platforms. Content recommendation platforms present themselves as a means for news organizations to “save journalism from Facebook’s death grip” (Fiegerman Citation2016), by “enabling publishers to compete with walled garden behemoths” (CitationTaboola 2021a); this article suggests that the result is somewhat different.

Content recommendation platforms are part of the hyper-connected world of the present day, described by Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal (Citation2018) as a “platform society.” Platforms are a technological construct and economic model for the social web. Their programmability and informational architecture facilitate connecting and exchanging data with external applications (Helmond Citation2015, Gillespie Citation2010). More specifically, in the context of cultural production, Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy (Citation2021) define platforms “as data infrastructures that facilitate, aggregate, monetize, and govern interactions between end-users and content and service providers” (p. 17).

Examples of such platforms include Google (Alphabet, Inc.) and Facebook (Meta, Inc.)—companies which exercise significant control over the online flow of information. Like other types of information, the distribution of news is also moderated by platforms (Shearer and Mitchell Citation2021). Given the influence of these platforms on access and distribution, scholars have argued that news publishers have become platform-dependent (Meese and Hurcombe Citation2021, Nielsen and Ganter Citation2017). This process is often described as “the platformization of news” (Nieborg and Poell Citation2018, Nielsen and Ganter Citation2017).

Nieborg and Poell (Citation2018) conceptualize the platformization of cultural industries as the intertwined penetration of the platforms’ economic models, modes of governance, and data infrastructures into the Web and app ecosystems. This encroachment by the platforms’ economic framework is evident in the evolution of a multisided market where different actors meet to communicate, interact, and sell industry-related “goods”—in this case, advertising (Helmond Citation2015, Gillespie Citation2010; Rochet and Tirole Citation2003). In the process of platformization, the news industry has moved from a historically two-sided mass-media market, in which news organizations and audiences interacted directly (Anderson and Gabszewicz Citation2006), to a multisided market in which news competes with all types of content for the audience’s attention. Since "social media and mobile media are general-purpose platforms" (Nieborg and Poell Citation2018, 4283), in such a market structure the news is just another commodity—and thus dispensable.

The platforms’ distinctive mode of governance, sharpened through corporate ownership, terms of service, and content moderation policies, also affects the regulation of public spaces, by structuring “how content can be created, distributed, marketed, and monetized online” (Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy Citation2021, 81). For instance, since social media platforms are for many consumers the principal main gateway to news reports, platforms now control the visibility of news stories and the size of the audiences that these stories will reach. Thus, they can determine the traffic that a news organization will garner, as well as its revenues (Nielsen and Ganter Citation2018).

Finally, the infrastructural framework of platforms links cultural production and its distribution on platforms through its material and computational elements, such as interfaces, algorithms, and data services (Nieborg and Poell Citation2018). Examples of the penetration of this infrastructural framework into news organizations are manifold: from the incorporation of the “like” and “share” buttons into the websites of news organization (Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013), through the construction of audience engagement through audience metrics (Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018) to the use of tools such as Google Analytics to generate insights and shape (even possibly drive) editorial decisions.

A review of the empirical evidence of the platformization of news suggests that thus far, scholarly attention has mainly been directed to social media platforms (e.g. Ferrer-Conill and Tandoc Citation2018), reflecting their dominance as content curators. This article discusses the platformization of news by drawing attention to content recommendation platforms, and to two companies specifically—Taboola and Outbrain (henceforth T/O). As described below, T/O are not general-purpose platforms that build on a different business model than that of social media platforms. T/O’s model is based on sharing advertising revenues with publishers, which has a marked bearing on their relationship with news organizations.

In order to explicate the role that content-recommendation platforms play in the platformization of news, this article is structured as follows. First, we review T/O’s business models. We then demonstrate the implications of the embedding of content-recommendation platforms in the websites of news organizations both within and across the main news organizations in Israel, by focusing on the distribution of sponsored content produced by publishers, and the display of the content of competing publishers on news websites. We discuss our findings through an analysis of the possible implications of T/O’s distribution model for journalism, and for their audiences.

Making Money from News: Taboola and Outbrain’s Business Mode

Selling “eyeballs” and consumer attention to advertisers has always been a key source of income in the news publishing industry (Nelson and Webster Citation2016). Even though cracks have been forced into this model during the digital age, it remains a dominant source of income (Newman Citation2021). A relatively new take on this model was developed by Taboola and Outbrain, two major global content recommendation companiesFootnote1specializing in advertisement placement on news websites. Outbrain was founded in 2006, as a startup offering an RSS recommendation widget for blogs and websites. Taboola was founded in 2007 as a Video-over-IP solution startup. In 2010, Taboola pivoted its business model to video discovery and distribution; (Internet Archive Citation2022a) as did Outbrain (Internet Archive Citation2022b). Today, Outbrain’s news recommendation widget is embedded in 485,209 websites worldwide. Of these, 24,080 are news and media websites, including the BBC, CNN, The Washington Post, and Buzzfeed. Taboola is embedded in 482,479 websites worldwide; 24,364 of these are news and media sites, including The Independent, NBC News, FOX News Network, and Business Insider (SimilarTech Citation2022).

T/O’s current business model relies on matchmaking between advertisers, publishers, and data brokers. Advertisers and marketers purchase the right to place ads on a network of widgets, hosted across the websites of a range of publishers. The content of the widget is personalized based on user-tracking data, collected through planting third and first-party cookies on the publishers’ websites. Advertisers submit bids for programmatic auctions through the platforms’ campaign dashboards, which grants them access to the platform’s targeting based on data gained from user traces and data brokers. The advertisements are then displayed in the platform’s widget, which is embedded in the publishers’ website code. The widgets display to the website audience an algorithmically curated blend of advertisements, sponsored content, and news stories.

On the publisher side, T/O offer multiple monetization venues, anchored by two factors: a) traffic redirection across sites—A news organization can sell “attention” when users on their website click on an ad or sponsored content, and can also benefit from attention directed to their website; b) monetization of content created by the publishers. More specifically, news organizations “lease” their advertisement space. T/O sign exclusive, long-term partnership agreements with publishers, to embed their widgets on the publisher’s websites and mobile apps. In these widgets, the platforms serve up advertisements in video format. The videos are paid for by impression and box ads formats, according to a pay-per-click (PPC) model. The platforms collect the payment for the advertisements, and “share” this with the publisher after deducting a commission (of up to 30%) under the specific terms of the agreement between the parties. Second, publishers benefit from the retargeting and distribution capabilities of the platforms. As a result, the targeted editorial content promoted in the widget is viewed by audiences who are likely to engage with it. Third, the publishers can use the widget space (on their own site, or on other news sites) to promote sponsored content that they themselves created, enhancing its visibility and the monetization prospects of such pages. In this capacity, publishers are acting as advertisers. Lastly, the widget enables the publisher to benefit from e-commerce opportunities promoted on the platform widget (Goetzen Citation2021). In 2021, this monetization program yielded substantial earnings for news organizations: Taboola paid publishers $859,595 M, and Outbrain paid $743,579 M (SEC Citation2022a; SEC Citation2022b).

Two caveats should be noted here. First, the barriers to entry into publisher partnerships with Taboola and Outbrain are high. While the official literature of both companies claims that they work with publishers of all sizes, a range of reports from the advertising industry indicate that the platforms require minimum traffic requirements from prospective publisher partners—ranging from 500k to 1 M monthly page views for Taboola, and 10 M for Outbrain (Monetizepros Citation2022). Second, while they claim to increase traffic to news websites, the platforms also encourage publishers to reinvest up to 25% of their earnings into the platform’s Traffic Acquisition systems, through which they have access to new audiences (CitationTaboola 2022a).

Beyond the direct financial benefits that publishers gain through their cooperation with the two platforms, both platforms provide the publishers with data analytics, user behavior analytics services, and internal content recommendation algorithms, all geared to increasing publishers’ monetization prospects for the entire website, without charge (Outbrain Citation2021b). This also includes free access to “Engage” (Outbrain) and “Newsroom” (Taboola). These are algorithms and AI recommendation tools designed to maximize the monetization potential of every article outside of the widget area (Taboola Citation2022b).

As outlined above, both companies offer similar models, with no distinct differences in technology or services provided to publishers and advertisers. The companies are so alike that in 2019 they signed a preliminary merger agreement (Hanley, Citation2020), eventually aborted in 2020. The official reason given was a disagreement regarding their net worth post-COVID 19. What is interesting here for our case study is the regulators’ approach to this merger, as this sheds light on the companies’ business model, market position, and possible competition. While the U.S. and German regulatory bodies cleared the deal, the U.K.'s Competition and Market Authority (CMA) called for an in-depth investigation. CMA called attention to the fact that the companies constitute a duopoly in the content-recommendation market, which is a distinct segment of the digital advertising market. As such, Facebook and Google could not be considered competitors of T/O. This informed the concerns voiced that if the merger were to go through, it will create a barrier that would prevent publishers from easily switching between platforms. In 2021, the companies initiated separate market floatations. Outbrain became a public company through an IPO, with a market cap of $1.12B. Taboola became a public company through a Special Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC), valued at $2.6B (Taboola Citation2021b).

Taboola and Outbrain’s News Distribution Model: A Recursive Space

As noted above, one major concern that has resulted from the platformization of news is the diminishing degree of control that news organizations have over their content distribution. Indeed, Nieborg and Poell (Citation2018) argue that the ultimate aim of the platforms is to completely take over the distribution infrastructure of news organizations, and to “decontextualize and unbundle news content even further, and potentially reduce news organizations to mere content developers” (p. 4288). While this argument can be applied to both social media and T/O, this section demonstrates how T/O’s distribution model differs from the dominant model of social media. Social media platforms offer what Nieborg and Poell (Citation2018) called “native hosting and monetization programs.” What this means is that “rather than drawing audiences to their own websites, news organizations hand over their content to platforms, where it can be consumed, bought, and connected to advertisements (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018, 53). By way of contrast, T/O’s main product aims to “unbundle” and “rebundle” content within and across news organizations’ websites: News pieces and audiences are first taken out of their original website context and recirculated (unbundling); they are then aggregated in an assemblage of news content drawn from various sources, alongside advertisements and sponsored content, all tied together in a specific space (rebundling). Since each new partnership expands the space through which content recommendations are rebundled, the platforms’ network of publishers constitute its distribution interface. Importantly, while in the case of social media, news organizations are the entities being hosted in a centralized interface, here the tables are turned somewhat: news organizations host the widget, in addition to being content providers. Therefore, the structural space created is a recursive one: much like a matryoshka doll, news websites present their own content that envelopes and hosts T/O’s widget, which in turn hosts the news organizations’ content.

The following section of this article argues that although T/O can be seen as another example of news platformization, their specific distribution (and platformization) model brings with it a different set of challenges for both the news industry and its audiences. To explore the possible implications of such a model, we begin by presenting a data analysis of this space, mapping the content served by T/O across the websites of their publisher clients in Israel. We then discuss the findings of this analysis in light of the companies’ business models, using data drawn from their websites and IPO filing documents.

Case study

Our analysis presents a case study of the circulation of content types by Taboola and Outbrain in Israel. We focus on two spatial aspects of the collaboration between publishers and platforms: the curation of content types within news websites, and the circulation of content types across publisher websites.

Data Collection

We collected articles recommended by Taboola and Outbrain across the Israeli news sphere using Webtrack, a research extension for the Chrome browser that tracks users’ web-surfing activity (Christner et al. Citation2022). The extension was installed by a sample of 230 consenting participants.

Webtrack records when a user enters and leaves a website, creating three files: a HTML file with the page content; a JSON file containing the metadata, (such as a hashed user ID, entry and exit timestamps, domain name, URL, page title, and page meta-description); and a record in a MySQL database containing the domain name, time stamps, and hashed user IDs. It should be stressed that user IDs are anonymized, and no personal information about the users was collected.

User Sample

Participants were recruited by iPanel, a large online research company that maintains a large panel of survey participants in Israel. They were recruited via ads on Google, Facebook, and other popular sites. Panelists are asked to take part in periodic surveys in exchange for incentives (gift cards). We sampled 230 participants who regularly consume news online from leading Israeli news websites (Ynet, Calcalist, N12, Mako, Maariv, and Makor Rishon). The sample resembled a representative Israeli sample in terms of demographics (61% male; age: 38% between the ages 18-29, 21% between ages 30-39, 15% between 40-49, 19% between 50-59 and 6% above 60; education: 6% finished high school, 22% completed high school with diploma, 25% had non-academic higher education and 47% had an academic degree; income: 33% had below average income, 35% reported an average income and 32% reported above average income).

Procedure

Participants were instructed to log online each day for a period of one week using Google Chrome on a desktop computer, and to visit the news websites that they regularly read. Once on the news website, they were asked to click on at least 10 news articles. To ensure the full loading of all recommended content, we asked participants to scroll down until the end of each article page, and then to wait for at least 10 s before moving on to the next article. We used this method to collect the data in batches of seven consecutive days per participant. Data collection took place for three weeks in total between 2-23 March 2021.

Overall, we collected 222,888 content items, from nine websites, served by Taboola and Outbrain to our participants (see ; this covers close to 70% of traffic to Israeli news sites according to simillarweb.com).Footnote2

Table 1. An overview of the Israeli news publishers included in the study.

Classification of Content Types

We used a manual coding schema to classify the types of content circulated by Taboola and Outbrain within and across publishers’ websites. Each news website included in our sample displayed content recommendations. We relied on the following three parameters to determine the classification of the content in accordance with T/O content production and distribution processes: Who produced the content and where is the content displayed? Is the content journalistic or sponsored? And, who promoted its distribution on T/O? It should be noted that the last two are not necessarily aligned.

Who Produced the Content (Content Creators), and Where is the Content Displayed (Content Hosts)?

Source domain: the website that created the recommended content.

Target domain: the website on which the recommended content was displayed.

We use the term in-house content to refer to cases where the content displayed in the widget on Publisher X’s website was also produced by Publisher X [source domain = target domain]. We use the term competitor content to refer to instances where the source and target domains are different, such as when the widget on Publisher X’s website presents content produced by Publisher Y. Later in the study, we created an additional distinction, which sorted content according to media ownership. Items in which the source domain and the target domain were owned by publishers from the same media group were categorized as “Ingroup”; items where different media groups owned the source and target domains were classified as “Cross-group.”

Is the Content Journalistic or Sponsored?

We first distinguished between advertisements and content produced by publishers. We defined advertisements as all cases in which the target domain is not a publisher: for instance, recommended content that points to a landing page of a real estate company. 50% of the items were commercial ads. This type of content did not form part of our analysis.

The remaining content (97,499 items) was analyzed further. We categorized each article according to the three following parameters:

Journalistic content: news content (e.g. a news article, a magazine article, or an interview).

Sponsored content: content designed to look like journalistic content but incorporating a disclosure stating that the content was sponsored by a commercial entity (Hardy Citation2021) (e.g. an article promoting financial services, indicating that a bank had paid the publisher to publish it).

Who Sponsored Content Distribution?

T/O’s widgets rebundle in-house journalistic content alongside sponsored content. With sponsored distribution, the widgets display the identity of the content’s promoter (i.e. who is T/O’s client-advertiser). Similar to the difficulty in discerning between journalistic and sponsored content, it was also difficult to determine the identity of the content promoter, and to distinguish it from content creators (our first category) or the sponsors of the content (our second category). Given the complexity of T/O’s multisided market, the client-advertiser could be one of three entities: a) the publisher itself, promoting either journalistic or sponsored content; b) an advertiser, who directly paid a publisher for sponsored content on their website and has also paid T/O to circulate that content; c) any other interested third party using Taboola or Outbrain to circulate content (commercial or journalistic) on their network (i.e. a political party running a campaign on Taboola to push positive journalistic coverage of their candidate). We use the term Third-Party Sponsor when Taboola or Outbrain tagged the sponsor as a commercial entity (e.g. Domino’s Pizza). In all other cases, the client-advertisers were the publishers (for examples of categories see Table 2, Online Appendix).

Findings

The data collected through Webtrack confirm T/O’s claims that 50% of the content recommendations they serve are commercial ads (as noted previously, this content type is not included in the analysis reported below). The data also resonates with the relative market share of each platform in Israel, as Taboola contributes 68% of the content items and Outbrain 32%.

The Blurring of Journalistic and Promotional Content within Publisher’s Websites

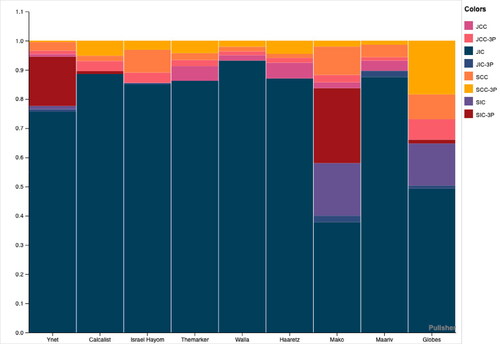

We found that on each publisher’s website, the most dominant content is journalistic in-house content (JIC, Average = 76.70%, StD==.0195) followed by sponsored in-house content (SIC, SIC-3P. Average = 9.49%, STD=.0165; see ). These proportions hold both in the case of Outbrain (93.56%) and Taboola (87.85%). The similar proportions suggest that the process of algorithmic curation identified this blend of content as optimal for monetization.

Figure 2. Content type distribution within each of the studied publishers’ websites (by percentage).

News publishers constantly compete against each other for the attention of a shared audience and advertising revenue. This is particularly relevant in a small market such as Israel. Historically, this competition has encouraged publishers to refrain from linking to their competitors’ websites (Chang et al. Citation2012), and to employ a minimalist approach to mentions of credits and attributions on their websites. Our findings indicate that partnership with Taboola and Outbrain has an impact on these norms. 13.81% of the displayed articles are produced by competitors (sum of the following categories: JCC, JCC-3P, SCC, SCC-3P, StD = 0.0163). It is important to note here that T/O allow publishers to control the types of content displayed on their website. Taboola, for instance, tells potential advertisers: “Your campaign items will only have the chance to appear on publishers that accept your specific type of content.” (Taboola Citation2023a). In light of this, the findings here indicate that the publishers did not prohibit Taboola and Outbrain from displaying competitor content on their websites.

Lastly, while the literature has traditionally distinguished between sponsored and journalistic content, it seems that this distinction is lacking at the present time, in the sense that journalistic content is utilized for commercial purposes and other third-party interests. For example: our data collection took place ahead of a general election in Israel; political parties promoted many news articles on Taboola and Outbrain as part of their campaigning.

The Creation of Indirect Network Effects

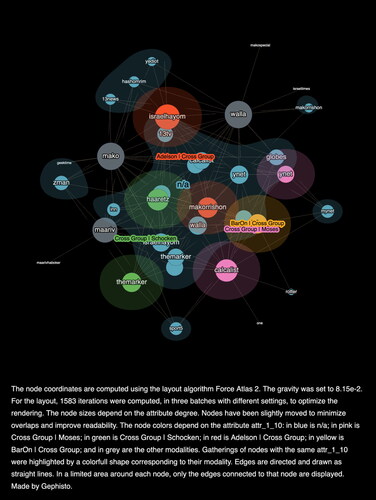

We now turn to look at the network formed by the hyperlinks connecting the widgets. is a bipartite network of all the publishers’ content displayed in the source domains in the dataset, showing the content flows from source domains, colored according to media group, to target domains, which are colored blue.

Figure 3. A bipartite network of hyperlinks from source domains to target domains in the studied data set.

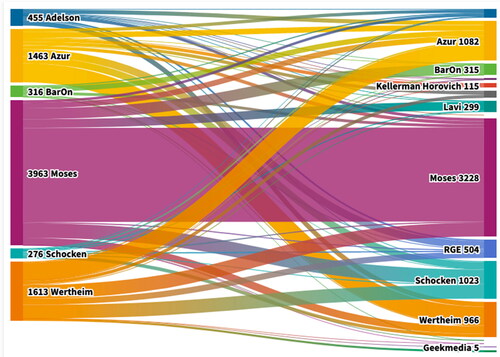

The network view allows us to examine how recommended content travels across media groups. The Israeli news ecosystem consists of a few large media groups that own several publisher websites (Mozes, Wertheim, Azur); smaller media groups that own two or three different publisher websites (Schocken, Adelson); and individual publisher websites of different sizes and audience reach. Aggregation of the circulation of content according to the media group demonstrates how large media groups benefit from the T/O distribution model. As we can see in , more than 90% of the content produced by the largest media groups—Mozes (99%), Wertheim (90%), and Azure (94%)—circulates within the media group, thereby increasing the group owners’ revenues across their websites. In comparison, the in-group display rate of the smaller media groups is about 65%. Thus, in contrast to T/O’s portrayal of their business model as a “win-win” partnership (SEC Citation2021a, 89), not all partners are equal; the competition that small networks create between publishers gives way to rich publishers getting richer.

Figure 4. An alluvial diagram showing content flows within and across source and target domains, aggregated by media groups.

We also found that small independent journalism websites, who themselves are not partners of Taboola and Outbrain, use these platforms as clients for increasing the distribution of their journalistic content. As can be seen in , these publishers (Zman and Hashomrim) are located at the periphery of the network, as they are only target domains. Although one could argue that small publishers have always had to fight for audience attention, T/O’s business model pushes market forces to the extreme. Alongside the fact that large media groups acquire more power than smaller groups (as demonstrated previously), we also see that marginalized players must assume an advertiser’s role, and pay T/O for the opportunity to present their news content to potential audiences.

The network structure that emerged in our analysis is a classic example of indirect network effects, which is a result of the platform economy. “Network effects” refers to the cycle through which: “the more numerous the users who use a platform, the more valuable that platform becomes for everyone else” (Srnicek Citation2017, p. 24). As mentioned above, the British CMA report noted that the merged T/O’s market share would create a strong network effect. Yet, when platforms achieve this status, an indirect network effect also becomes likely. When a platform reaches a sizable audience, dominant content creators also enjoy exponential growth. As Poell et al. note:

Direct network effects and economies of scale are leveraged by both platform companies and complementors…. complementors are poised to take advantage of a platform’s winner-take-all dynamics [and] …the distribution of transactions in platform markets is highly skewed as a very small percentage of complementors is responsible for capturing the majority of downloads, views, likes, revenue, and, ultimately, profit (p. 43).

The Possible Implications of New Platformization by Content Recommendation Platforms

Thus far, we have described the differences between T/O’s content distribution model and that of social media platforms. We then examined the circulation of content types within and across publisher websites in a national context. In this section, we discuss the possible implications of T/O’s distribution model on journalism and on news audiences. Our discussion is normatively informed by the vast body of literature in journalism studies documenting the importance of an independent press, free to fulfill its role as the Fourth Estate of viable democracies without commercial pressure (e.g. Artemas, Vos, and Duffy Citation2018; Poell and van Dijck, Citation2014).

Audiences

Both Taboola and Outbrain define their business model as operating a two-sided market – mediating between advertisers and publishers (the UK CMA report subsequently reiterated this description). However, such a framing leaves out one key side of the market—the end user. T/O’s use of first-party cookies allows them to directly trace and profile the publishers’ audiences. These platforms do not have subscribers, and there is no requirement to log in to their services. Nevertheless, it could be argued that a de facto relationship is created between the two sides, whereby user data is collected and personalized recommendations are served. While this relationship re-enacts the “classic transaction” of the platform economy, our point here is that the transaction is built on misleading elements.

First, news organization audiences are “forced” to become T/O users. T/O’s infrastructural embedding in the code of publishers’ websites is also reflected in their intertwined interfaces: users consume the rebundled content directly on the publishers’ websites. Consequently, opt-in user agreements are not required. Instead: “You are a User when you visit a page of a website or application of one of Outbrain’s partners where the Outbrain widget is installed or our recommendations are placed” (Outbrain.com, Citation2021a). Because no overt login mechanism is engaged, users will not know that any interaction with the content displayed in the widget has legally binding force, transforming them from “readers of a news website” to users of an algorithmic service.

This infrastructural entanglement also translates into thrusting liability upon the publishers. T/O’s code, embedded within their publishers’ websites, allows the platforms to directly track the publishers’ audiences—while complying with the letter, if not the spirit, of the European General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR)—by relying on the publishers’ cookies and beacons policies (Taboola Citation2020a; Outbrain Citation2022). Since it is the publisher who is required to secure consent from their users with regard to the use of data, T/O’s compliance is a derivative of the publisher’s own compliance.

This model serves both T/O and publishers. Unlike Facebook and Google, which build rich profiles of identified users, T/O claim that they can create similar reader profiles based on their behavior across websites and devices. Thus, their business model rests on the “userification” of unidentified users. This would not be possible without the publishers’ cooperation, via the planting of first-party cookies on their websites; or without reliance on users’ trust in the publisher’s website. In the face of rapidly evolving conceptualizations of online privacy and surveillance (Olds Citation2022), first-party cookies are more sustainable than third-party cookies and other trackers. Facing a reality made up of publishes with varying levels of use of third-party cookies, and of compliance with GDPR guidelines (Libert, Graves, and Nielsen, Citation2018; Sørensen and Kosta, Citation2019), T/O state that thanks to their first-party access (Taboola, Citation2023b), algorithms, and AI capabilities they are “well positioned to adapt and continue to provide key data insights to our media partners without cookies” (Outbrain Citation2021b: 19). From the publisher’s perspective, T/O offer optimization models that are based on tracking user behavior across the network of publishers—meaning that it is based on data that far exceeds the data available to a single publisher.

Second, the literature expresses some concerns about the ways in which sponsored content makes use of the audiences’ inability to identify it as such (Hardy Citation2021). This also harms the integrity of communication channels; it is “parasitic, destroying what it feeds on; advertisers want to harness reader trust but in doing so undermine it” (Hardy Citation2021, p. 875). We have shown that T/O intensify these processes, by creating an architecture based on various forms of subterfuge. For users to understand that they are consuming advertisements (and not objective news content), they need to engage the following mechanisms. First, to understand that although the widget does contain news content, it is actually a commercial space in which news, sponsored content and advertisements are designed to look alike. Second, to understand that the tags marking sponsored content can be confusing, and publishers may be tagged as sponsors of content. Lastly, since this space uses first-party cookies, they still present widget content even if the users use ad blockers, which often give users the illusion of protection. The need for such a complex process of deconstruction and decoding results directly from platformization. The specific form of content-bundling that these platforms offer serves as the first layer of disguise; the location of the space they occupy serves as the second layer.

Third, the ubiquity of T/O’s interfaces, which are distributed across its partner-publishers’ websites and not through a defined entry point, can lead users to assume they are freely surfing the Web while in fact, they have been blinkered and set onto a limited track directed by an algorithm that personalizes content for monetization reasons. Thus, although T/O use the rhetoric of the open web to offer publishers an alternative to walled-gardened social media, the size of their open web is in fact determined by the number of publishers who chose to exclusively contract with each platform.

News Organizations

Looking at this type of platformization from the perspective of news organizations, we would like to echo Lynch, who argued that “although native advertising serves as a temporary (and partial) solution to the crisis in the news industry, it might also—paradoxically—disrupt the core functions of journalism in order to ensure the news industry’s survival” (Lynch Citation2018, 5). As we intended to demonstrate, T/O’s models are hardly a sustainable standalone financial solution, and they disrupt core journalistic values. First, T/O frame their model as a remedy for the crisis in the news industry, stressing the alignment in business interests between them and the news industry. For example, Taboola declares: “We do not compete with our digital property partners for users’ attention. Our motivations are aligned: when our partners win, we win, and we grow together.” (SEC Citation2021a, 89). This rhetoric is also evident in their self-definition. Outbrain describes itself as “a leading recommendation platform powering the open web” (SEC Citation2021b); Taboola self-identifies as a “a technology company that powers recommendations across the Open Web” (taboola.com, 2021). The heavy reliance of both platforms on the ethos of the open web facilitates a favorable contrast between their business model and that of dominant Internet platforms like Google and Facebook, whose closed, “walled-garden” architectures are proprietary.

The juxtaposition between T/O and Facebook/Google is deliberate, of course. As noted above, because T/O rely on first-party cookies, their dependence on news organizations (as of now) is stronger than that of social media companies. But rhetoric is not enough. To allow infrastructural expansion and use of content, they offer publishers a different monetization model, and sign “partnership agreements.” The definition of publishers as partners—in contrast to the term “clients,” used to refer to advertisers—is consistent across all the companies’ documentation. It is also evident in the structure of the Taboola and Outbrain websites, which presents a clear distinction between the sections aimed at their “clients,” advertisers, and their “partners,” publishers. In this, it reflects Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal (Citation2018) claim regarding the relationship between business models and website architecture.

Business Model

A closer look at the partnership between T/O and publishers reveals that it is mostly based on binding contracts that demand exclusivity. Exclusivity is not only achieved legally, but also through infrastructuralization, given that the embedding of the platform’s code in the publishers’ website creates high switching costs. The British CMA report refers to this exclusivity as one of the concerns expressed by publishers. These concerns materialized in 2021, when the Israeli Competition Authority fined Taboola and Ynet—Israel’s most prominent news website—for coordinating a letter sent by Ynet to the Competition Authority, supporting the merger with Outbrain. Taken as a whole, what is framed as partnership is far from egalitarian.

Second, Lynch’s warnings about the disruption of “the core functions of journalism” also come into play with the creep of algorithmic curation into other parts of news websites (Bodó Citation2019). Scholarship addressing the algorithmic curation of news has raised concerns regarding the appropriation of power away from editors, and the possible implications for gate-keeping processes (DeVito Citation2017). While editors presumably make editorial decisions based on journalistic norms, algorithms are black boxes (Van Dijck and Poell Citation2013, Napoli Citation2014). Indeed, the success stories that T/O showcase on their websites suggest that tech companies’ goals may differ from those of traditional journalism. Their way of achieving these goals is by personalized news (in contrast to journalistic norms of newsworthiness). For instance, Taboola offers news-organizations the following service: “Homepage For You supplements editors’ existing ability, as always, to own and curate their homepage experiences with a new A.I. layer that surfaces content readers might find more relevant and personalized to their interests. With it, publishers can continue to maintain their editorial integrity and brand voice, while enabling readers to find more relevant content during every visit, resulting in increased readership and engagement.”

Considering this service through the prism of content rebundling (Van Dijck, Poell, and Waal Citation2018), the focus on the individual user is telling.

T/O’s framework not only entails personalization, but also offers specific interpretation of user engagement (Nelson Citation2018). See, for instance, this quote aimed at publishers: “Outbrain’s algorithms are built to service individual readers. This drives the best experience for audiences and also drives the best results via high CTR and RPM.” (outbrain.com, 2021). The platforms thus translate editorial criteria into advertising terms. Much like the metaphor of a hammer that sees the world as nothing but nails waiting to be hit, the algorithms consider every content item in terms of marketing goals such as RPM (Revenue per Mille) and CTR (Click-Through Rates). This is a clear example of what Bodó described as “third-party personalization technologies [that] arrive with certain values embedded in them” (Citation2019, 1069).

Yet T/O do not only suggest that algorithmic tools be employed outside of their widget. As part of their binding contract, T/O demand that web-crawlers are given unfettered access to the publisher’s entire website content, to track visitors, optimize their services, and drive traffic to the publisher’s news content by recycling articles (Taboola Citation2020b). Moreover, as T/O’s networks of publishers expand to include “publishers of all sizes and categories” these companies have hired several “trust and safety” startups, as well as personnel, to review and monitor publishers’ entire content on an ongoing basis, to assess whether they indeed meet their terms of use. Thus, the infrastructural expansion of T/O, from the widget to the entire website, also expands these companies’ modes of governance—turning them into reviewers of publisher content, de-facto setting criteria for “quality” publishing.

Another threat to journalist norms is more directly related to the fact that the T/O model is based on sponsored content. As such, it changes not only the incentive for their publishers-partners to produce such content, but also for the entire market. Changes in the relationship between newsrooms and their marketing departments have become evident in the last few years, with the two sides working ever more closely together (Artemas, Vos, and Duffy Citation2018; Hardy Citation2021)—replacing what was once described as the separation between Church and State (Cornia, Sehl, and Nielsen Citation2020). Nevertheless, T/O’s business model creates even greater incentives for publishers to dedicate both their websites and marketing departments to creating sponsored content, as the model amplifies the circulation of such content, transferring it to other publishers-partners. Perhaps even more important is the worry expressed by scholars, that “[n]ative advertising violates principles of editorial independence, or artistic integrity, because it creates the risk that “non-advertising” content will be shaped in accordance with advertisers’ wishes” (Hardy Citation2021). Specifically, as was demonstrated in the example that opened the article, this business model allows journalistic content to be repurposed as advertisement, while the original publisher benefits from this unintended use. Although no empirical data that testifies to this was collected, one can speculate that the changing set of incentives may introduce new economic pressures into the newsroom.

Lastly, T/O’s multisided market changes the power dynamics between publishers. As a space within and between publishers, it allows for content flows across competing publishers, and thus creates strange bedfellows. This circulation of content across publishers is profitable. Yet, just as social media content flattens the differences between content types (Kalogeropoulos, Fletcher, and Nielsen Citation2019), the uniform design of the ubiquitous platform underplays publishers’ branding. Alongside this flattening effect, we also see a “winner takes all” effect at work, where three categories can be identified. The strongest are the big media groups who dominate the space and circulate only in-house content. They are followed by small media groups and independent websites, who are still partners (see ). Last, we have small publishers, who are not partners and have to buy audience attention (see ). Thus, in the same way that big platforms drained traffic from publishers’ websites by appropriating attention from publishers to themselves (Gerlitz and Helmond Citation2013), it may be argued that T/O are now doing the same to non-partner publishers. This is another demonstration of the implications of network effects. As Poell, Nieborg, and Duffy (Citation2021), note: “Although relatively open boundaries make platforms economically accessible, such accessibility does not necessarily entail a democratization of the cultural industries. To the contrary, platform- dependent cultural production is riddled with economic inequalities and asymmetries” (p. 43).

Limitations

This research has several limitations. First, it is focused only on two companies and looks at the distribution of content in only one national context. Future research may examine content-recommendation platforms in comparative contexts. Second, while we collected personalized content recommended to individual users, we did not compare the ads served to participants in our sample with their demographic data. We have done so purposefully, in order to refrain from collecting personal data. Nevertheless, future research may also address the effects of personalization on content flows in content-recommendation platforms. Finally, although the data we collected allowed a mapping of content circulation patterns across the studied publishers’ websites, we are unable to explore the reasons behind these patterns. Since the contracts signed between the platforms and each of the publishers are secret and differ from one publisher to another, we are unable to infer whether content circulation patterns are an outcome of differences between publishers’ spending costs, or adjustments of their widgets to allow and exclude certain content. Future research may address this gap by conducting interviews with publishers about their partnership with content recommendation platforms.

Conclusions

Going out from the vast literature on the platformization of news in the past decade, this article has explored the possible implications of the business model of content-recommendation platforms on news publishers and their audiences. In essence, T/O model intensifies two trends characterizing the evolution of the news industry in the past decades (Cornia, Sehl, and Nielsen Citation2020): the blurring boundaries between editorial content and advertising in the form of sponsored content (Hardy Citation2021); and the algorithmic curation of news, which collects indirect user signals to provide personalized recommendations (Bodó Citation2019, Thurman, Lewis, and Kunert Citation2021). Merging these models, T/O creates a unique autonomous space outside the news organizations’ sovereignty. This in-between space is governed by advertising logic disguised as editorial curation – an advertising space curated by algorithms, which auto-displays ads, sponsored content disguised as news, alongside news. The result is a space in which, for the first time, content originally produced as news is being resold and redistributed as advertisements by various stakeholders. Furthermore, this space uniquely exhibits content of other news organizations hosted on a rival organization’s website, thereby resembling news aggregators within the news organizations’ websites.

That platforms such as Taboola and Outbrain portray their business models as a solution to the demise of news publishing in face of Internet giants, is only one narrative that fuels the architecture of this space. Our findings have demonstrated that such processes create a ubiquitous platform distributed across a network of publisher websites, in which platform logic determines and optimizes the curation of news content, while constantly blurring the boundaries between advertising, sponsored-content and journalism. T/O leverage the credibility, audiences, and reputation of news publishers, and promote the logic of surveillance capitalism—fueled by insincere tracking, profiling and grouping of news audiences to serve them personalized ads—as the business model that would save online journalism from the firm grip of giant platforms.

In the last few years, T/O’s growth has positioned them as leading actors in the advertising and publishing industries, to the extent that their possible merger was weighed in terms of antitrust and competition. As these companies continue to grow, so too their business model evolves (Nieborg and Helmond Citation2019). Our analysis has focused on the post-merger period, with the two companies “going public” separately. At this point in time, we noted how the two companies emphasized that the success of their business model was dependent upon premium, high-quality publishers. However, it may be argued—as the lifecycle of other platforms suggests (Poell et al. Citation2021)—that as T/O continue to grow, their dependence on quality journalism will decline, allowing them to capitalize on their network effect. The fact that both platforms currently partner with tens of thousands of websites takes them further from their self-portrayed marriage of content recommendation and quality journalism, and closer to the relationship between platforms and any other content producer

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Table_2_Content_type_categories.docx

Download MS Word (15.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In terms of global reach: while the founders of both companies are Israeli, both are headquartered in New York. Outbrain is incorporated in the US State of Delaware, but has offices in 18 cities around the world and operates in 55 countries. Taboola has 24 offices worldwide, and operates (under US and Israeli law) in 80 countries. 64% of Taboola’s traffic share comes from the USA, Germany, Brazil, France, and Japan. Outbrain leads the recommendation market in the USA, Taiwan, Russia, Italy, and other countries. Taboola is a market leader in France, India, Brazil, Poland, and other countries. (Similartech, Citation2022).

2 It should be noted that we ran a separate crawl, automatically collecting recommended content served by Taboola and Outbrain from the same news websites during the same period. The findings from the data collected from the crawl are similar to that collected by the user panel. Thus, while this article focuses only on the findings collected from the browser add-on, we can confirm that potential biases or personalization effects were controlled for in advance.

References

- Anderson, S. P., and J. J. Gabszewicz. 2006. “The Media and Advertising: A Tale of Two-Sided Markets.” Handbook of the Economics of Art and Culture 1: 567–614.

- Artemas, Katie, Tim P. Vos, and Margaret Duffy. 2018. “Journalism Hits a Wall: Rhetorical Construction of Newspapers’ Editorial and Advertising Relationship.” Journalism Studies 19 (7): 1004–1020.

- Bodó, Balázs. 2019. “Selling News to Audiences–a Qualitative Inquiry into the Emerging Logics of Algorithmic News Personalization in European Quality News Media.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 1054–1075.

- Chang, Tsan-Kuo, Brian G. Southwell, Hyung-Min Lee, and Yejin Hong. 2012. “Jurisdictional Protectionism in Online News: American Journalists and Their Perceptions of Hyperlinks.” New Media & Society 14 (4): 684–700.

- Christner, Clara, Aleksandra Urman, Silke Adam, and Michaela Maier. 2022. “Automated Tracking Approaches for Studying Online Media Use: A Critical Review and Recommendations.” Communication Methods and Measures 16 (2): 79–95.

- Cornia, Alessio, Annika Sehl, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2020. “We No Longer Live in a Time of Separation’: A Comparative Analysis of How Editorial and Commercial Integration Became a Norm.” Journalism 21 (2): 172–190.

- DeVito, Michael A. 2017. “From Editors to Algorithms: A Values-Based Approach to Understanding Story Selection in the Facebook News Feed.” Digital Journalism 5 (6): 753–773.

- Ferrer-Conill, Raul, and Edson C. Tandoc. Jr. 2018. “The Audience-Oriented Editor: Making Sense of the Audience in the Newsroom.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 436–453.

- Fiegerman, Seth. 2016. “The New Media Startup Pitch: Save Journalism From Facebook’s Death Grip.” Mashable. Accessed May 25, 2016. https://mashable.com/article/facebook-winter-is-coming

- Gerlitz, Carolin, and Anne Helmond. 2013. “The Like Economy: Social Buttons and the Data-Intensive Web.” New Media & Society 15 (8): 1348–1365.

- Gillespie, Tarleton. 2010. “The Politics of ‘Platforms.” New Media & Society 12 (3): 347–364.

- Goetzen, Nina. 2021. “Taboola Acquires Connexity to Help Publishers Push into Ecommerce.” emarketer. Accessed July 26, 2021. https://www.emarketer.com/content/taboola-acquires-connexity-help-publishers-push-ecommerce

- Habib-Valdhorn, Shiri. 2021. “We are the Robin Hood of the Internet.” Globes. Accessed January 28, 2021. https://en.globes.co.il/en/article-we-are-the-robin-hood-of-the-internet-1001358790

- Hanley, Daniel. 2020. “Ad Mergers Won’t Save Journalism. Strict Merger Rules Would.” Wired. Accessed September 10, 2022. https://www.wired.com/story/opinion-ad-mergers-wont-save-journalism-strict-merger-rules-would/

- Hardy, Jonathan. 2021. “Sponsored Editorial Content in Digital Journalism: Mapping the Merging of Media and Marketing.” Digital Journalism 9 (7): 865–886.

- Helmond, Anne. 2015. “The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready.” Social Media + Society 1 (2). doi: 10.1177/2056305115603080.

- Internet Archive. 2022a. “Taboola” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20101231062546/http:/taboola.com:80/

- Internet Archive. 2022b. “Outbrain” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://web.archive.org/web/20100401223329/http:/www.outbrain.com/

- Rochet, Jean-Charles, and Jean Tirole. 2003. “Platform Competition in Two-Sided Markets.” Journal of the European Economic Association 1 (4): 990–1029.

- Kalogeropoulos, Antonis, Richard Fletcher, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2019. “News Brand Attribution in Distributed Environments: Do People Know Where They Get Their News?” New Media & Society 21 (3): 583–601.

- Libert, Timothy, Lucas Graves, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen. 2018. “Changes in Third-Party Content on European News Websites after GDPR.” In Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reports: Factsheet, 1–7. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

- Lynch, Lisa. 2018. Native Advertising: Advertorial Disruption in the 21st-Century News Feed. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Meese, James, and Edward Hurcombe. 2021. “Facebook, News Media and Platform Dependency: The Institutional Impacts of News Distribution on Social Platforms.” New Media & Society 23 (8): 2367–2384.

- Monetizepros. 2022. “Taboola Review for Publishers” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://monetizepros.com/ad-network-reviews/taboola/

- Napoli, Philip M. 2014. “Automated Media: An Institutional Theory Perspective on Algorithmic Media Production and Consumption.” Communication Theory 24 (3): 340–360.

- Nelson, Jacob L. 2018. “The Elusive Engagement Metric.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 528–544.

- Nelson, Jacob L., and James G. Webster. 2016. “Audience Currencies in the Age of Big Data.” International Journal on Media Management 18 (1): 9–24.

- Newman, Nic. 2021. “Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends and Predictions 2021.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/journalism-media-and-technology-trends-and-predictions-2021

- Nieborg, David B., and Anne Helmond. 2019. “The Political Economy of Facebook’s Platformization in the Mobile Ecosystem: Facebook Messenger as a Platform Instance.” Media, Culture, and Society 41 (2): 196–218.

- Nieborg, David B., and Thomas Poell. 2018. “The Platformization of Cultural Production: Theorizing the Contingent Cultural Commodity.” New Media & Society 20 (11): 4275–4292.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, and Sarah Anne Ganter. 2018. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617.

- Nielsen, Rasmus Kleis, and Sarah Anne Ganter. 2017. “Dealing with Digital Intermediaries: A Case Study of the Relations between Publishers and Platforms.” New Media & Society 20 (4): 1600–1617.

- Olds, D. 2022. “What Do Those Pesky “Cookie Preferences” Pop-Ups Really Mean?” Wired. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.wired.com/story/what-do-cookie-preferences-pop-ups-mean/.

- Outbrain. 2021a. “Privacy Center”. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.outbrain.com/privacy/

- Outbrain. 2021b. “Euronews Increases RPM by 34% with Outbrain Smartlogic” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.outbrain.com/case-studies/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/77617_CaseStudy_Euronews_Superside_FV-2.pdf

- Outbrain. 2022. “Can I Control What Shows Up on My Widget?” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.outbrain.com/help/publishers/can-control-shows-widget/

- Poell, Thomas, David B. Nieborg, and Brooke Erin Duffy. 2021. Platforms and Cultural Production. Oxford, UK: Polity Press.

- Poell, Thomas, and José Van Dijck. 2014. “Social Media and Journalistic Independence.” In Media Independence: Working with Freedom or Working for Free? edited by J. Bennett and N. Strange. London: Routledge.

- SEC. 2021a. “F-1 Foreign Private Issuer Registration.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1840502/000114036121024263/nt10026806x1_f1.htm

- SEC. 2021b. “Form S-1 Outbrain Inc.” Accessed Febuary 17, 2023. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1454938/000110465921086945/tm2113258-10_s1.htm

- SEC. 2022a. “Form 10-K Outbrain Inc.” Accessed Febuary 17, 2023. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1454938/000145493822000003/outbrain-20211231.htm

- SEC. 2022b. “Form 20-F Taboola.com Ltd.” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1840502/000114036122010978/brhc10035439_20f.htm

- Shearer, Elisa, and Amy Mitchell. 2021. “News Use Across Social Media Platforms in 2020” Pew Research Center, January 2021. Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2021/01/PJ_2021.01.12_News-and-Social-Media_FINAL.pdf

- SimilarTech. 2022. “Outbrain-vs-taboola” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.similartech.com/compare/outbrain-vs-taboola

- Sørensen, Jannick, and Sokol Kosta. 2019. “Before and After GDP R: The Changes in Third Party Presence at Public and Private European Websites.” In The World Wide Web Conference, 1590–1600. San Francisco, CA: ACM.

- Srnicek, Nick. 2017. Platform Capitalism. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Taboola. 2020a. “Consent Management Technical Integration Guidelines for Publishers” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.taboola.com//wp-content/uploads/2020/07/consent-management-technical-integration-guidelines-publishers.pdf

- Taboola. 2020b. “TABOOLA.COM LTD. DIGITAL PROPERTY SERVICES AGREEMENT TERMS AND CONDITIONS” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.taboola.com//wp-content/uploads/2020/09/taboola-israel-publisher-agreement-3.0d-2.pdf

- Taboola. 2021a. “Analyst Day Presentation” Last modified March 30, 2021. https://www.taboola.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/taboola-analyst-day-presentation_033021.pdf

- Taboola. 2021b. “Taboola, a Global Leader In Powering Recommendations for the Open Web, to Become NYSE Listed at an Implied $2.6 Billion Valuation via a Merger with ION Acquisition Corp. 1 Ltd.” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://www.taboola.com/press-release/taboola-goes-public

- Taboola. 2022a. “Traffic Acquisition.” Accessed June 26, 2022. https://pubhelp.taboola.com/hc/en-us/articles/360003181434-Traffic-Acquisition

- Taboola. 2022b. “Taboola Launches “Homepage For You” Artificial Intelligence Technology, Empowering Editors To Make Homepages as Personalized and Engaging as the World’s Top Social Apps; Offering Drives More Than 30% Increase in CTRs.” Accessed June 26, 2022. taboola.com/press-release/taboola-launches-homepage-for-you

- Taboola. 2023a. “How Taboola Works” Accessed February 17, 2023. https://help.taboola.com/hc/en-us/articles/115006597307-How-Taboola-Works

- Taboola. 2023b. “Taboola Privacy Policy”. Accessed February 17, 2023. https://www.taboola.com/policies/privacy-policy#users

- Thurman, N., S. C. Lewis, and J. Kunert. eds. 2021. Algorithms, Automation, and News: New Directions in the Study of Computation and Journalism. London: Routledge.

- Van Dijck, José, and Thomas Poell. 2013. “Understanding Social Media Logic.” Media and Communication 1 (1): 2–14.

- Van Dijck, José, Thomas Poell, and Martijn De Waal. 2018. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.