Abstract

The global field of fact-checking organizations has experienced a dramatic shift in focus since 2016, from checking claims by politicians and other public figures to policing viral misinformation on social networks. What practitioners call “debunking,” once a minor focus, now dominates the agenda of leading outlets and accounts for the bulk of fact-checks produced worldwide, driven in part by commercial partnerships between fact-checkers and platform companies. This study investigates what this sudden realignment means for fact-checkers themselves, drawing on interviews and meta-journalistic discourse to examine the impact on how these organizations assign value and draw boundaries in their growing transnational field. We highlight different discursive strategies fact-checkers use to explain the debunking turn, depending on their own field position, and show how shifting boundaries reflect wider concerns about autonomy from platform partners. We suggest that debunking discourse illustrates an incipient shift away from the “public reason” model implicit in journalism’s professional logic, to a more instrumental, “public health” model of newswork adapted to a digital media environment dominated by platform companies.

Introduction

The global field of fact-checking organizations has expanded rapidly in recent years, with nearly 400 nonpartisan fact-checkers operating in 108 countries in 2021—a 2.5-fold increase from 2016 (Stencel, Ryan, and Luther Citation2022). About half of outlets today are based in Africa, Asia, and South America, a dramatic increase from five years ago. Total global output has grown even more quickly, seeing a five-fold rise between 2018 and 2020 (Van Damme Citation2021).

These trends are tied to a more profound change for fact-checkers: A rapid shift in the field’s center of gravity from checking claims by politicians and other public figures, to policing viral misinformation on social networks—what practitioners call “debunking.” As alarm mounted over “fake news” after 2016, leading fact-checkers began to shift attention from elite political discourse to debunking viral hoaxes, fakes, and conspiracy theories (Graves and Mantzarlis Citation2020; Mantzarlis Citation2018). Newer outlets focus overwhelmingly on such social media content, which as of 2020 accounts for the lion’s share of fact-checks produced worldwide (Van Damme Citation2021). One driver of this shift is partnerships between fact-checkers and social media firms—particularly Meta, whose third-party fact-checking program (or “3PFC”) pays fact-checking partners in 119 countries to debunk misinformation on Facebook and Instagram.

This study investigates what the rise of debunking means for fact-checkers. We ask how practitioners talk about the differences between checking politicians and policing social media, and what this reveals about the way these organizations assign value and status in their evolving transnational field. We find that despite similarities in these forms of fact-checking, practitioners assign lower status to debunking work—or perceive that others do—because of associations with outlandish and unserious content. This gives rise to internal boundary work which, we argue, reflects larger concerns about the field’s autonomy from outside stakeholders like governments and major tech firms. Finally, we identify a new strategic rhetoric that elevates protecting audiences over informing them, raising basic questions about fact-checkers’ relationship with the public.

The next section offers an overview of the global fact-checking movement. We draw on recent scholarship but also practitioners’ efforts to define “debunking” as against political fact-checking; such metajournalistic discourse (Carlson Citation2016) has been a key site for identifying and negotiating new practices among fact-checkers (e.g. Cheruiyot and Ferrer-Conill Citation2018; Graves Citation2016; Luengo and García-Marín Citation2020). Introducing the study’s main theoretical framework, we then suggest that the turn to debunking should be approached through the literature on professional boundaries (Gieryn Citation1983). After reviewing data and methods, we present the study’s findings, organized according to discourse about the objects, methods, and strategic concerns of debunking work. Our discussion argues that debunking discourse signals a shift away from the “public reason” model implicit in journalism’s professional logic, to a more instrumental, “public health” model of newswork mediated by platform partnerships—one in which “the goal is for people not to read the story.”

The Global Fact-Checking Movement

The organizations studied here practice “external” or ex post fact-checking, producing evidence-based assessments of the veracity of public texts such as political claims, news reports, and social media posts (Graves and Amazeen Citation2019; Mantzarlis Citation2018). (Internal or ex ante fact-checking as practiced in journalism and publishing seeks to eliminate errors before publication.) Some of the earliest external fact-checking sites, like Snopes.com (1995) in the US and E-farsas (2002) in Brazil, specialized in debunking email hoaxes and urban legends circulating online. However, the fact-checking movement which took shape in the US from the mid-2000s, grounded in professional journalism, centered on what practitioners refer to as “political fact-checking”: holding politicians and other public figures to account for false statements, especially during elections (Graves Citation2016).

This political focus persisted as fact-checking spread globally, with waves of new outlets modeled directly after US sites such as FactCheck.org and PolitiFact. Studies highlight the diversity of organizations in the global fact-checking movement (Graves Citation2018; Lauer Citation2021; Moreno-Gil, Ramon, and Rodríguez-Martínez Citation2021; Singer Citation2021). Some fact-checkers do not identify as journalists, and many operate from civil society groups or universities; worldwide, about 60% of fact-checking outlets are based in media organizations (Stencel, Ryan, and Luther Citation2022). Despite this diversity, scholars chart growing collaboration, standardization, and professionalization in the field (e.g. Graves and Lauer Citation2020; Mare and Munoriyarwa Citation2022; Moreno-Gil, Ramon, and Rodríguez-Martínez Citation2021). Fact-checkers launched the annual Global Fact conference in 2014; they formed an association, the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), in 2015; and in 2016 they produced a Code of Principles (henceforth “IFCN Code”), with over 130 accredited signatories today.

The Turn to “Debunking”

Fighting viral online misinformation remained a secondary focus for most fact-checkers through 2016, rarely discussed on the IFCN mailing list or at Global Fact conferences (see Graves and Lauer Citation2020). However, the emphasis began shifting as global concern grew over what scholars call “information disorder” (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). The 2017 Global Fact conference included the first panels focused explicitly on “fake news.” A Washington Post report on that meeting reflected the continued dominance of political fact-checking, while pointing to signs of change where “newer fact-checking groups are dedicated to debunking manipulated images and video, often using sophisticated forensic tools to spot suspicious content that turns out to be fake” (Lee Citation2017).

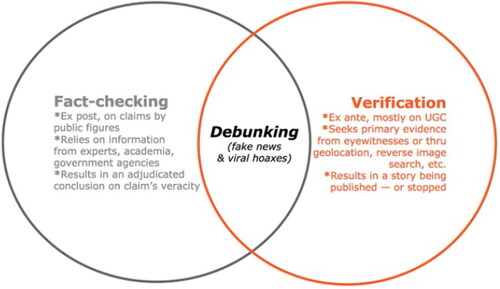

The choice of the term “debunking” reflected a growing association, among journalists, with specific targets (“manipulated images and video”) and methods (“sophisticated forensic tools”) of fact-checking. As early as 2014 the label was being applied to efforts to combat a rising tide of fake stories and images on social media (e.g. Silverman Citation2014). A 2014 Buzzfeed report defined the “viral debunk” as a “form-fitting response to a new style of hoax, much in same the way that Snopes and Hoax-Slayer were an answer to ungoverned email hoaxes, or that Politifact and FactCheck.org arose in response to…false statements by public figures” (Warzel Citation2014). Asked to define debunking, the then-director of the IFCN tweeted a Venn diagram placing it at the intersection of political fact-checking and internal verification of eyewitness evidence; he explained, “Debunking is a subset of fact-checking and requires a specific set of skills that are in common with verification,” such as determining whether an image has been doctored (Mantzarlis Citation2017, Citation2018) (). The association with special skills becomes salient in this study, although in practice much debunking work relies on basic reporting methods.

Figure 1. This Venn diagram, produced by the IFCN director in 2017, shows how practitioners distinguish debunking of viral content from fact checks of political claims.

A “second wave” (Mantzarlis Citation2018) of fact-checking projects launched after 2016 focus mainly or exclusively on debunking. These include AFP Fact Check, the “digital verification service” launched in 2017 that has become the largest fact-checker in the world, covering more than 80 countries from six regional bureaus. Established fact-checkers have also focused more on debunking (Graves and Mantzarlis Citation2020; Siwakoti et al. Citation2021); fact-checks targeting social media content surged from 5% to about two-thirds of global output between 2016 and 2020 (Van Damme Citation2021).Footnote1 The debunking turn has been accelerated by alarm about the “infodemic” of online COVID-19 misinformation, the dominant priority for fact-checkers globally during the pandemic (see e.g. Suárez Citation2020).

The field’s realignment has become a point of discussion among fact-checkers. One concern is whether the two styles of fact-checking require distinct skills and resources; some organizations segregate them into separate editorial operations (see e.g. Mantas Citation2020; Funke Citation2017). Another question is whether policing social media has pulled some organizations away from what they see as their core mission of keeping politicians honest (Graves and Mantzarlis Citation2020; Full Fact Citation2020).

More fundamentally, the debunking turn is tightly tied to fact-checkers’ partnerships with platform companies. Meta’s 3PFC, the largest program, launched in late 2016 in response to an open letter “from the world’s fact-checkers” (IFCN Citation2016). As of mid-2022 the program includes more than 80 fact-checking partners—who must be signatories of the IFCN Code—paid to debunk misinformation circulated by Facebook and Instagram users (exempting politicians and party organizations) according to a six-part rating system. The 3PFC has become the primary funding source for many outlets and fueled the spread of fact-checking globally (see Van Damme Citation2021, 51–52), inviting questions about Meta’s influence over the field (e.g. Pasternack Citation2020; Silverman and Mac Citation2020). Other paid partnerships involve WhatsApp, TikTok, and Twitter. Less has been documented publicly about the TikTok and Twitter initiatives, which do not involve the IFCN and may include private consulting work in addition to fact-checking (see Bélair-Gagnon et al. Citation2023).

Debunking as Boundary Work and Boundary Object

Professional discourses are sites for building, tending, and sometimes shifting the boundaries that define and delimit authority over particular spheres of knowledge production. This basic tenet of the sociology of scientific and professional disciplines proceeds from a view of status or legitimacy as fundamentally relational, both within and between fields (Abbott Citation1988; Bourdieu Citation1993; Gieryn Citation1983). This study draws mainly on Gieryn’s (Citation1983) notion of “boundary work,” originally applied to the discursive strategies scientists employ to reinforce their own epistemic authority—typically, by marking knowledge-producing practices of rival groups as illegitimate. In addition to expulsion of rivals, as Lamont and Molnár (Citation2002) note, boundary work encompasses expansion to incorporate new actors and practices as well as protection of autonomy from powerful interests outside the field.

In journalism studies, scholars have used ‘boundary work’ to understand how journalists reproduce status distinctions within the field (e.g. Maares and Hanusch Citation2022; Nygaard Citation2021) and navigate outside jurisdictional challenges (e.g. Cheruiyot et al. Citation2021; Bélair-Gagnon and Holton Citation2018; Eldridge Citation2018) at a moment when “economic, technological, and cultural changes … make boundary work explicit and inescapable” (Carlson Citation2015, 9). A crucial dynamic here is that boundaries marking what’s outside a field typically are reinforced by hierarchies within the field, and vice versa. Thus, Sjøvaag (Citation2015, 101) argues that the boundary between hard and soft news—”one of the strongest dichotomies of news production”—transforms concerns about autonomy from outside commercial influence into an internal value scheme for judging newswork. Revers (Citation2014) shows how internal struggles for status among statehouse reporters involved performing autonomy from external political sources. Similarly, Graves (Citation2016, 52) highlights efforts by leading US fact-checkers to “reinforce their own claim to journalistic legitimacy” by delegitimizing partisan counterparts, for instance by refusing to cite or appear at events with them.

Globally, a challenge has been how to draw a boundary around legitimate fact-checking in a movement that spans many different kinds of organizations, including non-journalistic ones, working in diverse political contexts. The IFCN Code, which emerged from discussions at the 2016 Global Fact conference, requires signatories to be evaluated annually by outside assessors for compliance to five core “commitments” centered on transparency and nonpartisanship. Beyond promoting common standards, this professionalizing initiative has increased the authority of the IFCN as the institutional home of fact-checkers; invited new forms of governance, such as the IFCN Advisory Board (established 2016) and IFCN Bylaws (published in 2020); and helped pave the way for platform partnerships, which in turn enhance IFCN’s gatekeeping role. However, the existence of multiple forms of attachment to the fact-checking community keeps boundaries somewhat permeable and flexible (Graves and Lauer Citation2020). While certain IFCN programs are restricted to Code signatories, a wider sphere of fact-checkers attends Global Fact and participates in IFCN discussions and collaborations. Broadly, the diversity of the fact-checking movement can be read as boundary expansion (Graves Citation2018; Graves and Lauer Citation2020; Lauer Citation2021; Singer Citation2021) where “individuals, practices, norms, or organizations initially located outside the boundaries of journalism get brought in” (Carlson Citation2018, 3).

This raises the important point that professional discourses also work to efface the boundaries that separate domains of knowledge or practice. “Boundary objects” (Star and Griesemer Citation1989) refer to common reference points—material and discursive—which help to coordinate action and meaning among groups with different understandings of a common project. Several studies examine “news” itself as a boundary object in projects where reporters, programmers, and data specialists work together (e.g. Lewis and Usher Citation2016). Similarly, the term “fact-checking” has been seen as a “discursive boundary object” (Dunbar-Hester Citation2013), easing discourse by toggling between a looser common meaning and more precise definitions among different groups of specialists (Graves Citation2018).

Data Collection and Analysis

This study employs a mix of qualitative methods and inductive analysis well suited to studying boundaries that define and maintain occupational fields (Lamont and Molnár Citation2002). To examine how fact-checkers make sense of the field’s rapid turn to debunking, we rely on 1) qualitative interviews with fact-checkers and 2) metajournalistic discourse (including published accounts and conference transcripts), as informed by 3) observation of Global Fact meetings.

Interviews were conducted between October 2020 and July 2021 as part of a larger global research project focused on misinformation and technological change. This project used interviews with journalists, fact-checkers, platform executives, and other stakeholders to study how emerging technologies affect the distribution of misinformation and journalistic responses to the same. This paper draws on a subset of 39 semi-structured interviews conducted with fact-checkers globally, recruited from IFCN members and by snowball sampling. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, interviews were conducted online, and lasted between 45 and 90 min; interviewees gave written or recorded consent under study protocols approved by two university ethics boards.

Interviews focused on fact-checking practices, technologies used, funding models, platform partnerships, collaborations, and views of current challenges in the misinformation landscape. We used a grounded approach (Corbin and Strauss Citation2014) to analyze interview transcripts with the qualitative analysis tool NVivo; researchers collaborated to identify recurring themes and refine codes through multiple rounds of coding across several related papers. Once the dichotomy of debunking and political fact-checking emerged as significant, subsequent coding focused on how informants defined each practice. This led to the insight that debunking discourse centered on objects, methods, and strategy in fact-checking; these codes then helped to highlight patterns based on organizational differences. Interview guides were also adjusted iteratively to develop emerging findings. For instance, later interviews with organizations practicing political fact-checking and debunking included questions about how they compare.

A secondary data source is virtual and archived conference sessions from Global Fact in 2020 and 2021. The decision to consider this material was guided by participation in previous Global Fact meetings, where the shift in the agenda from political fact-checking to debunking has been an explicit point of discussion (see Graves and Lauer Citation2020). Although 14 conference sessions were analyzed based on potential relevance, discourse quoted directly comes from three sessions held at Global Fact 7. These included a panel discussion focused on the turn toward debunking, where the lead author served as invited moderator.Footnote2

We note that while this analysis benefits from researchers’ participation in the global fact-checking milieu, such involvement can also be limiting, for instance by potentially highlighting practitioner views at the expense of an outside perspective. The three authors had varying levels of experience with fact-checking: one was completely new to the field, one has been a long-time participant-observer, and all helped organize the academic track at Global Fact 2021 and 2022. Maintaining critical distance speaks to an ongoing tension in journalism studies (Carlson Citation2018). We found that varying degrees of researchers’ proximity benefited coding and analysis, in surfacing a variety of themes. Panel discussions and interviews all took place in English, another potential limitation. While English is the default language of the fact-checking movement, it is likely that studying debunking discourse in specific languages and regions would offer new insights.

Finally, while themes developed below recur widely across these sources, we quote directly from a subset of 19 informants whose engagement typifies discourse around the “debunking turn.” We label these informants according to the focus of their organization: 1) DEB for outlets which exclusively or mainly debunk social media content; 2) POL for outlets which exclusively or mainly check claims by politicians and other public figures; and 3) MIX for organizations which engage substantially in both, either under a single brand or through separate operations (). Informants are identified according to region and organization type in order to preserve anonymity for interview subjects; one informant appears in interview as well as conference material, but is identified separately.

Table 1. Anonymized list of informants cited.

Results

Informants share the perception of a pronounced turn toward debunking across the fact-checking field, although they view this shift and the concerns it raises in different ways. Direct references to “debunking” and its variants came up in more than half of the 39 fact-checker interviews, often unprompted. This discourse reflected a broad sense that debunking is defined by 1) a focus on viral, anonymous, and often ridiculous content on social media (as opposed to more serious claims by politicians), and also by 2) forensic techniques such as image verification and network analysis (as opposed to conventional reporting methods, although in practice these prove important). Informants also highlighted 3) basic strategic concerns which govern debunking work but are absent from political fact-checking.

Our analysis considers each of these themes in turn, highlighting how perceptions of debunking vary for differently situated organizations—with a notable divide between newer outlets whose only mission is to police social media, and established ones that try to balance debunking with an original focus on checking political figures. These findings lay the ground for our discussion of how the debunking turn has unsettled boundaries in this young field, revealing deep concerns about platform influence—while highlighting a new model of impact that depends on that influence.

Objects of Debunking

Across various fact-checking outlets, we find wide consensus that “debunking” refers to exposing viral misinformation circulating on social media, typically with no clear origin or author. Informants also agree that this viral content is typically more outlandish and less serious than falsehoods in the political world, even as the two increasingly overlap. Organizations assign status in this new arena differently depending on their orientation: While pure debunkers defend the democratic value of their efforts generally, political fact-checkers draw lines between more and less legitimate debunking, and between mission- and profit-driven outlets doing this work.

For organizations that focus mainly on viral misinformation, “debunking” and “fact-checking” appear to be interchangeable. “My primary focus is to debunk misinformation that circulates online that may cause anxiety, harm, confusion … We try to fact-check things that are both very newsworthy or debunkable,” explained one editor (DEB1, Asia). A journalist with a debunking-focused project based in an investigative newsroom described its origins this way:

DEB3 (Europe): After a while we notice that one of the biggest threats to society are disinformation campaigns. We saw that by our work as investigative reporters, and we understood that this threat must be countered…. We need to debunk this disinformation, and this is the reason we started a fact-checking operation.

MIX4 (Europe): We used to only do fact checks, you know, very rigorous and very clear set of rules, but when covid started, we started seeing a lot more misinformation being shared on social media, and then again we wanted to be nimble, we wanted to be fast, so we started doing debunks as well, and a debunk is different to a fact check, because a debunk looks at something that’s gone viral on social media or being shared on social media, but we can’t find where the claim originally came from. So the fact check would say, you know, a politician said this in the parliament, is he right? While a debunk would say: This meme is being shared on Facebook and it says that it’s going to be a lockdown tomorrow, is it right?

Fact-checkers focused on debunking acknowledged that the work can seem less important than checking politicians, and offered various rationales for their efforts. “I do feel there is a certain feeling that debunking is seen as somehow inferior,” an editor explained at Global Fact 7, before countering that “little debunks” in the aggregate reveal organized disinformation networks (DEB2, Europe). Others noted that the line has blurred between the two, as politicians move from “normal fudging” to repeating “crazy rumors that somebody heard on Twitter” (DEB7, North America). The editor of an outlet with roots in political fact-checking made this argument:

MIX5 (North America): Yeah, what’s different is not what we’re writing about or the approach that we’re taking. It is that some of this stuff that was previously made by some no-named individuals who are running websites or sending out viral emails, that information is now being repeated or even sometimes created by political figures, mainstream political figures.

How fact-checkers view debunking work is colored by their participation in platform partnerships. Various informants acknowledged concerns that Meta’s 3PFC program has drawn attention away from checking political claims. “I’m sure we would be doing more misinformation even if there wasn’t the Facebook program. But I don’t think we’d be doing nearly as much as we’re doing,” one 3PFC partner stated (MIX6, North America). However, those who had not participated framed this issue most sharply. “Any fact-checking is good fact-checking in my view, but I think we also have to assess the reach of these things,” argued one former political fact-checker:

POL1 (North America): What I worry about are the ones that are being done because Facebook’s paying, but the reach isn’t that big. And what’s being missed is some claim that’s being said by a politician in the United States or France or wherever, and that’s a claim that’s reaching millions of people. And that’s not getting fact-checked because the fact-checkers are getting paid to check some silly claims about a horse dewormer on Facebook.

POL2 (North America): There’s a lot of repetitive stuff out there. If suddenly I got into the debunking business, what value added am I going to be bringing that is not already provided by [six other outlets]? Right? … There are other things out there to expose and fact check … than just debunking the latest stupid thing that appeared on Facebook.

In emphasizing their own rigorous standards, however, some 3PFC participants drew a sharp line between mission- and profit-driven outlets in the program. One Meta partner criticized debunking outlets which don’t do “any kind of fact check of ambition or substance” but instead pursue “the lowest hanging fruit to make a buck,” by picking “the easiest stuff that they can do the fastest, and that they can bill Facebook for” (MIX6, North America). Such comments echo broader concerns expressed at Global Fact conferences about outlets operating with lower standards in countries, such as India, that have experienced rapid booms in for-profit fact-checking since the 3PFC program was established.

Methods of Debunking

A second defining feature of debunking regards the methods involved: within the fact-checking community, debunking is commonly associated with specialized tools and techniques for identifying fake, manipulated, or out-of-context viral content. These sophisticated methods appear to be the domain of specialists within each outlet; our informants noted that in practice much or most debunking work relies on basic reporting skills, such as interviewing authoritative sources. As one summarized, online hoaxes “need to be either visually debunkable, or we need to use sources and comments from officials to debunk something” (DEB1, Asia).

Interviews highlighted a range of specialized tools and techniques associated with debunking. Three broad categories mentioned were technologies for identifying material taken out of context (e.g. geolocation and reverse image search), discovering manipulated or distorted content (e.g. doctored images), and tracing organized networks that distribute fake content. Recent Global Fact meetings have included workshops for applying such technologies (Graves and Lauer Citation2020).

Expertise in these techniques is typically limited to specific staff. When prompted, fact-checkers responded that “we have a couple of people who specialize in that … who are really good at searching to see if something’s real or not” (DEB7); “people wind up specializing” (MIX6); “people who are working with Facebook are more familiar with those tools” (MIX5). An informant whose organization operates separate debunking and political fact-checking sites said, “We have the strong belief that those are actually two very different kinds of fact-checking … in terms of names, instruments, tools, audiences, they are very different” (MIX3). Another fact-checker, experienced in sophisticated debunking methods, explained that journalism education rarely covers advanced verification: “It is not something I was taught at university for example 10 years ago, but I have learned it in the course of this job and my last job, how to go about debunking misinformation” (DEB1).

Informants involved in debunking work also stressed that many or most fact-checks of viral misinformation do not require specialized tools or techniques. In several interviews focusing on the 2020 US presidential election, fact-checkers highlighted the role of basic reporting skills. One fact-checker listed officials and experts interviewed to debunk a viral election fraud video, beginning with a call to an official “I’ve known for 45 years … who told people, ‘Hey, this is a good guy. Talk to him.’ And so that’s what opened the doors for me” (DEB7, North America). Another explained that debunking often consists of “false frame” fact-checks in which genuine evidence is used to support a false conclusion that only “officials” and “experts” can refute (MIX6, North America). A different informant gave the example of conspiracy theories around an authentic video from a ballot-counting station—”It was just people watching a video and saying that things were happening in that video that the video wasn’t necessarily showing, or wasn’t showing, according to election officials.” The fact-checker added,

DEB4 (North America): It’s pretty rare that we come across manipulated—I mean, not that it doesn’t happen, but I would say like the vast, vast majority of stuff that I check, isn’t manipulated. Particularly around the election stuff, it’s people who are misunderstanding the process or who are seeing something and intentionally sort of ascribing things that are happening that aren’t happening.

Despite overlaps between debunking and political fact-checking, informants highlighted practical differences arising from viral misinformation typically having no clear origin. “With a [political] fact check, we can ask the politician who made the claim, and say, you know, is this true? What evidence do you have to back it up? With a debunk you can’t do that,” one fact-checker noted (MIX4, Europe). Other debunks simply require no interviews. Many online hoaxes—e.g. recurring rumors that particular celebrities have died—are quickly debunked by linking to published evidence.

Strategy and Mission in Debunking Work

While fact-checkers define debunking in terms of particular targets or tools, the most significant departure from political fact-checking emerges in what might be called strategic concerns around each area of practice. A basic principle in debunking work is harm reduction: Fact-checkers express deep concern about amplifying misinformation on social media, and use “virality” as the main criterion in choosing what to debunk. For fact-checkers in platform partnerships, such strategic considerations promote a new understanding of the audience and mission of journalism.

Across our interviews, fact-checkers involved in debunking stressed how they decide whether a particular hoax has enough exposure that the benefits of debunking outweigh the risks of amplification. “Something we thought about a lot going back to 2016 and further back was, when is it worthwhile to debunk something, and when should we just leave it alone at the risk of giving it more oxygen?” a misinformation reporter explained (DEB5, North America). Some rely on tools such as Crowdtangle to measure misinformation spread. “We have discussions between the editors, but our general standard … would be we want something to have been shared or viewed thousands of times ideally,” noted an editor with a major debunking operation, adding later that “we don’t want to sort of amplify misinformation that has had three shares in two posts or something” (DEB1, Asia). At a different debunking outlet, an in-house tool is used to measure social-media engagement and create assignments—”I actually don’t generally choose what I fact check” (DEB4, North America). Another described how their organization shifted to cross-platform exposure as a litmus test:

MIX8 (South America): When I was starting fact-checking, you would say, “Oh, this is really viral on Facebook,” and you’d just have to write about it…. Something deserves to be fact checked now when it’s cross-platform. If something is just trending on Twitter, leave it there. It’s going to die. … It’s almost like an everyday discussion. Fact-checking can do harm if you don’t choose well what to fact check.

DEB6 (North America): There’s so much that we see and we don’t report on because we don’t want to amplify that messaging. But with the Trump campaign, there’s no way we can amplify further comments and claims by the President of the United States. So it was just like every single thing, you had to hit.

MIX2 (Europe): You have to be very careful where you intervene … It is not, I think, our mission to in any way censor what a politician can or cannot say. And then it’s up to the common discussion of the public forum, so to say, to decide [whether] that politician has to be listened to or not.

The tension between informing audiences and limiting their exposure to misinformation becomes clearest in fact-checkers’ work for social-media platforms, which rely on that work to delete or downrank content. For outlets with origins in political fact-checking, these partnerships offer an entirely new model of impact—one with no parallel in traditional journalism, and which fact-checkers have embraced widely despite concerns about suppressing speech. “Let’s just take shit down,” argued the editor of one 3PFC partner (MIX6, North America). Another fact-checker stressed that the Facebook partnership achieves real results:

MIX1 (Africa): It’s a really invaluable way for us to reduce the spread of false information on a social platform, because in our normal work, if a minister makes a false claim and it’s reported in the newspaper … suddenly it has just spread through society, whether online or offline… But with Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program, if we have a very dangerous claim, we know if we rate it, there will be a real-world reduction in how far that spreads and how many people are misled.

DEB 4 (North America): That’s a major difference between what I was doing before [as a journalist] and now. Before, you want as many people as possible to read your story, that’s a definition of success, right? You have a wide reach of people reading your story. In fact-checking, really the goal is for people not to read the story.

Discussion

This study examines how fact-checking organizations, as an increasingly well-defined, transnational professional field, have navigated the turn to debunking—a rapid, field-wide shift in the work defining this community. The broad picture is one of practitioners embracing new priorities and opportunities occasioned by mounting worldwide concern over viral online misinformation. However, the way different fact-checkers understand and approach this shift points to underlying concerns about their field’s autonomy. These tensions highlight the pressures and opportunities facing institutional journalism in a digital media environment dominated by platform companies. Our discussion focuses first on normative implications of these findings—the rise of an ethic of harm reduction—and then on the boundary work taking place as different organizations reconcile themselves to this shifting value scheme.

“Public Reason” vs. “Public Health”

The most far-reaching result of this study concerns how ties to platform companies may change fact-checkers’ conception of, and relationship to, their audiences. Our data show how debunking tends to decenter the core mission of informing a democratic public that has anchored journalism’s normative scheme in the era of professional news, providing a taken-for-granted rationale for conventional newswork routines (Gans Citation2003; Maras Citation2013; Schudson Citation1999). A tension between informing audiences, and protecting or even managing them, emerges in the strategic concerns around amplification and online backlash which attend debunking work, superseding traditional news values to a degree. Debunkers balance the traditional imperative to inform against a heightened sense of responsibility to minimize the potential harms of information, based on the understanding that “fact-checking can do harm if you don’t choose well what to fact check” (MIX8).

This emphasis on harm reduction does not exist in the same way in checking major public figures. Our informants understood this in both practical and normative terms: Fact-checkers cannot effectively suppress false claims by public officials, and doing so would raise censorship worries. Crucially, this harm-reduction ethic aligns with a new model of impact tied to platform partnerships, where accountability depends on private action rather than public exposure. Meta’s fact-checking partners celebrate that the platform actively reduces debunked content’s visibility, leading to “a real-world reduction in how far that spreads and how many people are misled” (MIX1). These arrangements effectively detach the “watchdog” role of journalism from the mechanism of publicity, allowing fact-checkers to identify serving the public interest with reporting directly to platform partners, who can “just take shit down” (MIX6). Some partners in Meta’s 3PFC program disavow any need to cultivate audiences, arguing that they succeed precisely when nobody sees their work.

The debunking turn highlights the dichotomy between what might be called a “public reason” mode of journalism, premised on the ‘informed citizen’ ideal (Schudson Citation1999), and a newer “public health” mode that attends explicitly to audience behaviors as a democratic concern. A wide literature addresses inadequacies of the “public reason” view, which rests on an idealized, Habermasian public sphere in which information-hungry citizens rely on news accounts for reasoned discussions and informed political choices (e.g. Achen and Bartels Citation2016; Kreiss Citation2018; Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2019). What Gans (Citation2003) calls “journalism’s theory of democracy”—that journalists’ core duty is to inform citizens, and that by reading news citizens become well-informed—places unrealistic demands on citizens, marginalizes traditions of activist or advocacy journalism, and allows reporters to disavow responsibility for the outcomes of their work. The fact that professional journalists historically have known little about their audience, writing instead for an imagined public much like themselves, reinforces the field’s pro-establishment biases and exclusions along lines of race, class, and gender (Callison and Young Citation2019, Gans Citation2004[1979]).

Though never an accurate picture, however, the “public reason” view anchors journalism’s professional norms and underpins a wider ethical system centered on the duty to readers. The imagined audience helps reporters to act as if serious, in-depth public affairs reporting matters. Studying the first generation of political fact-checkers, Graves (Citation2016) found they studiously ignored evidence that most traffic came from partisans unlikely to be persuaded by fact-checking. Much recent scholarship investigates challenges to journalism’s idealized public posed by quantified views of the digital audience (Anderson Citation2011), with the adoption of newsroom metrics that undercut assumptions of newsworthiness and threaten to erode commitment to public affairs reporting (Bélair-Gagnon et al. Citation2020; Christin Citation2020; Petre Citation2021).

The “public health” approach documented here also understands audiences algorithmically, attending to patterns of downstream interaction as input for future editorial decisions. It is deeply concerned with virality. But in contrast to metrics-driven journalism, the goal is to constrain engagement by strategically withholding information. The emphasis on harm reduction reflects a more general concern among journalists and scholars with the way that traditional news values—in a dynamic digital news ecosystem where the press no longer acts as gatekeeper—have been exploited by bad actors (Marwick and Lewis Citation2017; Donovan and boyd Citation2021). For instance, Phillips (Citation2018, 7) notes the distress experienced by journalists covering the “far-right fringe” who “just by showing up for work and doing their jobs as assigned … played directly into these groups’ public relations interests.” McClure Haughey et al. (Citation2020) find reporters on the “misinformation beat” agonizing about the unintended consequences of their work; as one laments, “I’m super concerned about [media manipulation]. …. I’ve also told other news organizations, ‘Hey, maybe don’t cover Q-Anon so fucking much.’” The new model of impact in platform partnerships avoids the professional tension that comes with recognizing the potential harms of reporting.

Boundary Work and Professional Autonomy

This rising model of impact tied to platform partnerships raises concerns about professional autonomy, giving rise to various forms of boundary work among differently positioned fact-checkers. The turn from political fact-checking to debunking can be characterized as a story of widening professional boundaries, but one in which the specific challenge is to accommodate a formerly marginal practice rising to dominance in terms of numbers, resources, and attention. This amounts to a collective redefinition of fact-checking around two distinct sets of practices; it requires cognitive, discursive, and affective effort to elaborate a shared schema that distinguishes the two forms while highlighting their commonality and protecting community ideals. Our analysis highlighted fact-checkers’ various rationales to resolve this tension: Viral hoaxes may be absurd, but debunking them is democratically important work; “mainstream political figures’’ now traffic in this material; fact-checking needed to become “nimble” to keep up with misinformation; paid debunking work subsidizes political fact-checking; and finally, working for platforms yields tangible results.

Still, clear professional divides surface in the shift from holding political actors accountable to policing anonymous, outlandish, and often trivial social media misinformation. Organizations that mainly practice debunking acknowledged that this work is seen as inferior, but stressed the harm viral rumors can do. Concerns are sharper for established political fact-checkers, who responded with three different forms of boundary-building, drawing lines within organizations, between organizations, or between subfields:

Some organizations segregate debunking and political fact-checking operationally, arguing that they involve different methods, require different expertise, and face distinct strategic challenges.

Other fact-checkers practice both genres under one roof, claiming to apply the same rigor to checking politicians and debunking viral hoaxes, but take pains to distinguish their own mission-driven work from commercially oriented rivals only going after “the lowest hanging fruit to make a buck” (MIX6).

Finally, some established political fact-checkers dismiss online hoaxes altogether as “stupid” and not worth their attention, and suggest that paid debunking may be distracting their peers from more important work.

It is vital to see that these internal status lines drawn among fact-checkers reflect their concerns about autonomy from external commercial or political influences. While our informants clearly value platform partnerships as vehicles for funding and impact (see also Full Fact Citation2020), many recognize the potential for falling standards if commercial incentives prevail—i.e. not doing work “of substance” (MIX6) or “getting paid to check some silly claims … on Facebook” (POL1). Fact-checkers thus draw lines between good and bad ways to work with platform companies, just as online journalists differentiate between degrees of “click-driven” reporting (e.g. Christin Citation2020; Moyo, Mare, and Matsilele Citation2019). Petre (Citation2021) shows writers for the blog network Gawker, which pioneered incentives for viral content, rationalizing their own “traffic whoring” posts that subsidized more substantial work—while dismissing rivals as truly “cynical” and lacking journalistic merit.

Such internal distinctions help reconcile professional and commercial imperatives in journalism, elevating work that embodies its democratic mission while also accommodating revenue needs. This logic becomes explicit in the repeated defense that paid debunking work subsidizes political fact-checking, “boosting our ability” (MIX7) rather than “taking away” (DEB2). The older divide between hard and soft news (Sjøvaag Citation2015) finds a clear echo in status distinctions between “rigorous” fact-checks of serious political claims and paid debunks targeting ridiculous hoaxes. This value scheme may not prove as durable, however; fact-checking is a young and organizationally diverse field that overlaps only partly with professional journalism. Rather than pandering to popular tastes, debunking (arguably) protects audiences by deprioritizing harmful traffic.

Finally, the ambiguity we note in debunking discourse may help to maintain community ties as this field changes. While not fully fledged boundary objects (Star and Griesemer Citation1989), terms like “fact-checking” and “debunking” do become highly specific in some contexts—e.g. a conference panel about advanced debunking techniques—while remaining quite flexible in general usage. Practitioners variously highlight contrasts or commonalities, as when organizations balancing the two styles reassure themselves that the core methods are “very consistent” (MIX5), “almost like breathing” (MIX6). Similarly, forensic tools and techniques have come to stand for debunking work even if most debunks don’t rely on them. The association is a useful one: It offers an easy and uncontentious distinction between debunking and political fact-checking, and, as a highly technical practice, it may also reflect aspirations among debunkers. Journalists strive for “the most attainable version” of the work their profession elevates, and find ways to affirm core values even if their own assignments don’t epitomize those values (Powers and Vera-Zambrano Citation2020, 74).

This study has analyzed “debunking discourse” to understand how fact-checkers are adjusting to the realignment of their field around paid work fighting online hoaxes for social media companies. We argue that this discourse reveals ongoing concerns about autonomy from platform partners, even as it highlights a new journalistic sensibility based on protecting rather than informing audiences—what we call a “public health” approach to newswork. In conclusion, we note that these developments can be read as one sign of professional values and routines adapting to concerns over “information disorder” (Wardle and Derakhshan Citation2017). Recent work highlights the need for journalists to not only give voice, but also create silence—spaces for “listening, observation, and reflection”—within which meaningful democratic publics can cohere (e.g. Ananny Citation2021, 141; Donovan and boyd Citation2021). The rising emphasis on harm reduction among fact-checkers may be understood through the lens of democratic silence. However, the debunking turn exposes unresolved tensions that may not exist in more deliberative silences: It promotes a view of the audience as potential victims of and vectors for misinformation, rather than thinking agents who might learn from journalists’ work. And it comes in the context of novel fee-for-service arrangements in which reporting work is used to drive algorithmic content moderation by private technology firms.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Fact-checkers in Facebook’s 3PFC partnership program are heavily overrepresented in this sample; however, the author reports a comparable increase in fact-checks of social media content among non-3PFC fact-checkers (Van Damme Citation2021: 53).

2 The panel, called “The elephant in the room: Fact-checking vs verification,” was proposed by one of the organizations interviewed for this study. The lead author served as invited moderator.

References

- Abbott, Andrew Delano. 1988. The System of Professions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Achen, Christopher H., and Larry M. Bartels. 2016. Democracy for Realists: Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Ananny, Mike. 2021. “Presence of Absence: Exploring the Democratic Significance of Silence.” In Digital Technology and Democratic Theory, edited by Lucy Bernholz, Hélène Landemore, and Rob Reich, 141–166. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Anderson, C. W. 2011. “Between Creative and Quantified Audiences.” Journalism 12 (5): 550–566.

- Bélair-Gagnon, V., R. Larsen, L. Graves, and O. Westlund. 2023. “Knowledge Work in Platform Fact-Checking Partnerships.” International Journal of Communication 17: 1169–1189.

- Bélair-Gagnon, Valerie, and Avery E. Holton. 2018. “Boundary Work, Interloper Media, and Analytics in Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 6 (4): 492–508.

- Bélair-Gagnon, Valerie, Rodrigo Zamith, and Avery E. Holton. 2020. “Role Orientations and Audience Metrics in Newsrooms.” Digital Journalism 8 (3): 347–366.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. European Perspectives. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Callison, Candis, and Mary Lynn Young. 2019. Reckoning: Journalism’s Limits and Possibilities. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carlson, Matt. 2015. “Introduction: The Many Boundaries of Journalism.” In Boundaries of Journalism, edited by Matt Carlson and Seth C. Lewis, 1–17. New York: Routledge.

- Carlson, Matt. 2016. “Metajournalistic Discourse and the Meanings of Journalism.” Communication Theory 26 (4): 349–368.

- Carlson, Matt. 2018. “Boundary Work.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by Tim P. Vos, M. Meier, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh, and A. Sehl. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cheruiyot, David, and Raul Ferrer-Conill. 2018. “Fact-Checking Africa’: Epistemologies, Data and the Expansion of Journalistic Discourse.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 964–975.

- Cheruiyot, David, J. Siguru Wahutu, Admire Mare, George Ogola, and Hayes Mawindi Mabweazara. 2021. “Making News outside Legacy Media: Peripheral Actors within an African Communication Ecology.” African Journalism Studies 42 (4): 1–14.

- Christin, Angèle. 2020. Metrics at Work. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2014. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 4th ed. London: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Donovan, Joan, and danah m Boyd. 2021. “Stop the Presses? Moving from Strategic Silence to Strategic Amplification in a Networked Media Ecosystem.” American Behavioral Scientist 65 (2): 333–350.

- Dunbar-Hester, Christina. 2013. “What’s Local? Localism as a Discursive Boundary Object in Low-Power Radio Policymaking.” Communication, Culture & Critique 6 (4): 502–524.

- Eldridge, Scott. 2018. Online Journalism from the Periphery. New York: Routledge.

- Full Fact. 2020. The Challenges of Online Fact Checking. London: Full Fact.

- Funke, Daniel. 2017. “This Bosnian Fact-Checking Outlet Launched to Go after Fake News.” Poynter.org. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2017/this-bosnian-fact-checking-outlet-launched-to-go-after-fake-news/.

- Gans, Herbert J. 2003. Democracy and the News. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gans, Herbert J. 2004. Deciding What’s News. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Gieryn, Thomas F. 1983. “Boundary-Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-Science.” American Sociological Review 48 (6): 781–795.

- Graves, Lucas, and Alexios Mantzarlis. 2020. “Amid Political Spin and Online Misinformation, Fact Checking Adapts.” The Political Quarterly 91 (3): 585–591.

- Graves, Lucas, and Laurens Lauer. 2020. “From Movement to Institution: The ‘Global Fact’ Summit as a Field-Configuring Event.” Sociologica 14 (2): 157–174.

- Graves, Lucas, and Michelle A. Amazeen. 2019. “Fact-Checking as Idea and Practice in Journalism.” In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication, edited by Jon F. Nussbaum. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Graves, Lucas. 2016. Deciding What’s True. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Graves, Lucas. 2018. “Boundaries Not Drawn: Mapping the Institutional Roots of the Global Fact-Checking Movement.” Journalism Studies 19 (5): 613–631.

- IFCN. 2016. “An Open Letter to Mark Zuckerberg from the World’s Fact-Checkers.” Poynter.org, November 17. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2016/an-open-letter-to-mark-zuckerberg-from-the-worlds-fact-checkers/.

- Kreiss, Daniel. 2018. “The Media Are about Identity, Not Information.” In Trump and the Media, edited by Pablo J. Boczkowski, and Zizi Papacharissi, 93–101. Cambridge, MA; London: MIT Press.

- Lamont, Michèle, and Virág Molnár. 2002. “The Study of Boundaries in the Social Sciences.” Annual Review of Sociology 28 (1): 167–195.

- Lauer, Laurens. 2021. “Similar Practice, Different Rationales: Political Fact-Checking around the World.” PhD thesis, University of Duisburg-Essen.

- Lee, Michelle Ye Hee. 2017. “Analysis | Fighting Falsehoods around the World.” Washington Post, July 14. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/fact-checker/wp/2017/07/14/fighting-falsehoods-around-the-world-a-dispatch-on-the-global-fact-checking-movement/.

- Lewis, Seth C., and Nikki Usher. 2016. “Trading Zones, Boundary Objects, and the Pursuit of News Innovation.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 22 (5): 543–560.

- Luengo, Maria, and David García-Marín. 2020. “The Performance of Truth.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 8 (3): 405–427.

- Maares, Phoebe, and Folker Hanusch. 2022. “Understanding Peripheral Journalism from the Boundary.” Digital Journalism. Advance online publication.

- Mantas, Harrison. 2020. “Italian Fact-Checking Organization Bolsters Its Effort to Fight Coronavirus Hoaxes.” Poynter.org, April 7. https://www.poynter.org/fact-checking/2020/italian-fact-checking-organization-bolsters-its-effort-to-fight-coronavirus-hoaxes/.

- Mantzarlis, Alexios. 2017. “What Is the Difference between Fact-Checking and Verification?” Tweet. Twitter, March 15. https://twitter.com/Mantzarlis/status/842028036325298176.

- Mantzarlis, Alexios. 2018. “Fact-Checking 101.” In “Journalism.” Fake News & Disinformation, edited by Cherilyn Ireton and Julie Posetti, 85–100. Paris: UNESCO.

- Maras, Steven. 2013. Objectivity in Journalism. Key Concepts in Journalism. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Mare, Admire, and Allen Munoriyarwa. 2022. “Guardians of Truth? Fact-Checking the ‘Disinfodemic’ in Southern Africa during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Journal of African Media Studies 14 (1): 63–79.

- Marwick, Alice, and Rebecca Lewis. 2017. Media Manipulation and Disinformation Online. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

- McClure Haughey, Melinda, Meena Devii Muralikumar, Cameron A. Wood, and Kate Starbird. 2020. “On the Misinformation Beat.” Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction 4 (CSCW2): 1–22.

- Moreno-Gil, Victoria, Xavier Ramon, and Ruth Rodríguez-Martínez. 2021. “Fact-Checking Interventions as Counteroffensives to Disinformation Growth.” Media and Communication 9 (1): 251–263.

- Moyo, Dumisani, Admire Mare, and Trust Matsilele. 2019. “Analytics-Driven Journalism?” Digital Journalism 7 (4): 490–506.

- Nygaard, Silje. 2021. “On the Mainstream/Alternative Continuum.” Digital Journalism. Advance online publication.

- Pasternack, Alex. 2020. “How Facebook Pressures Its Fact-Checkers.” Fast Company, August 20. https://www.fastcompany.com/90538655/facebook-is-quietly-pressuring-its-independent-fact-checkers-to-change-their-rulings.

- Petre, Caitlin. 2021. All the News That’s Fit to Click. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Phillips, Whitney. 2018. The Oxygen of Amplification. New York: Data & Society Research Institute.

- Powers, Matthew, and Sandra Vera-Zambrano. 2020. “What Are Journalists for Today?” In Rethinking Media Research for Changing Societies, edited by Matthew Powers and Adrienne Russell, 65–77. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Revers, Matthias. 2014. “Journalistic Professionalism as Performance and Boundary Work: Source Relations at the State House.” Journalism 15 (1): 37–52.

- Schudson, Michael. 1999. The Good Citizen: A History of American Civic Life. New York: Martin Kessler Books.

- Silverman, Craig, and Ryan Mac. 2020. “Facebook’s Preferential Treatment Of US Conservatives Puts Its Fact-Checking Program in Danger.” BuzzFeed News, August 13. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/facebook-arbiter-truth-fact-check-mark-zuckerberg.

- Silverman, Craig. 2014. “Publications Aim to Make Debunking as Popular as Fake Images.” Poynter.org, April 8. https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2014/publications-aim-to-make-debunking-as-popular-as-fake-images/.

- Singer, Jane. 2021. “Border Patrol: The Rise and Role of Fact-Checkers and Their Challenge to Journalists’ Normative Boundaries.” Journalism 22 (8): 1929–1946.

- Siwakoti, Samikshya, Kamya Yadav, Nicola Bariletto, Luca Zanotti, Ulaş Erdoğdu, and Jacob N. Shapiro. 2021. “How COVID Drove the Evolution of Fact-Checking.” Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review 2 (3): 1–23.

- Sjøvaag, Helle. 2015. “Hard News/Soft News: The Hierarchy of Genres and the Boundaries of the Profession.” In Boundaries of Journalism: Professionalism, Practices and Participation, edited by Carlson, Matt, and Seth C. Lewis, 101–117. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer. 1989. “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19 (3): 387–420.

- Stencel, Mark, Erica Ryan, and Joel Luther. 2022. “Fact-Checkers Extend Their Global Reach with 391 Outlets, but Growth Has Slowed.” Duke Reporters’ Lab, June 17. https://reporterslab.org/fact-checkers-extend-their-global-reach-with-391-outlets-but-growth-has-slowed/.

- Suárez, Eduardo. 2020. “How Fact-Checkers Are Fighting Coronavirus Misinformation Worldwide.” Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism, March 31. https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/how-fact-checkers-are-fighting-coronavirus-misinformation-worldwide.

- Van Damme, Thomas. 2021. “Global Trends in Fact-Checking: A Data-Driven Analysis of ClaimReview.” Master’s thesis, University of Antwerp.

- Wahl-Jorgensen, K. 2019. Emotions, Media and Politics. Hoboken, NJ: Polity.

- Wardle, Claire, and Hossein Derakhshan. 2017. Information Disorder. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

- Warzel, Charlie. 2014. “2014 Is the Year of the Viral Debunk.” BuzzFeed News, January 23. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/charliewarzel/2014-is-the-year-of-the-viral-debunk.