Abstract

The question of “who is a journalist?” has animated much discussion in journalism scholarship. Such discussions generally stem from the intersecting technological, economic, and social transformations journalism has faced in the twenty-first century. An equally relevant aspect, albeit one that has hitherto been less studied, is what a journalist looks like. Some studies have tackled this through, for example, examining depictions of journalists in popular culture, but artificial intelligence understandings of what a journalist is and what they look like have yet to receive research attention. While AI-enabled generative art has existed since the late 1990s, the ease and accessibility of these processes has greatly been boosted by providers like Midjourney which emerged since the 2020s and allow those without programming skills to easily create algorithmic images from text prompts. This study analyzes 84 images generated by AI from four “generic” keywords (“journalist,” “reporter,” “correspondent,” and “the press”) and three “specialized” ones (“news analyst,” “news commentator,” and “fact-checker”) over a six-month period. The results reveal an uneven distribution of gender and digital technology between the generic and specialized roles and prompt reflection on how AI perpetuates extant biases in the social world.

An oft-discussed topic in the digital journalism age is “Who is a journalist?” (see, e.g., Johnston and Wallace Citation2017; Ugland and Henderson Citation2007). Discussions within journalism studies on this matter have tended to focus around the “democratization of media production” that has been the purported consequence of the diffusion to mass publics of content creation technologies once restricted to journalists (Lewis, Kaufhold, and Lasorsa Citation2010, 164). However, there is a visual aspect to this question that is frequently overlooked. We know relatively little, for example, of the images that people (or technologies) recall (and create) when prompted to visualize a journalist. This is despite the persuasive power of images both generally (Coleman Citation2010) and in shaping understandings about journalism and how it ought to be practiced (Peters Citation2015).

This study explores how innovations in Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning – defined here as “the training of a machine to learn from data, recognize patterns, and make subsequent judgments, with little to no human intervention” (Broussard et al. Citation2019, 673) – can reveal subconscious understandings of what it means to be a journalist. Specifically, we do this through examining browser-based, algorithmic image-generating platforms to explore how four seemingly “generic” keywords (journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press) and three “specialized” ones (news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker) are depicted across image sets and, thus, how collective consciousness “sees” these words and visualizes their properties and relationships.

Literature Review

The literature review that follows introduces the study’s theoretical framework of metajournalistic discourse, discusses scholarship on visual representations of journalists, and provides an overview of AI, generative art and synthetic media. Context about the visual social semiotics elements that inform this study’s analysis are presented in the methods section.

Metajournalistic Discourse and the Social Construction of Journalism

The label metajournalistic discourse pertains to “public expressions evaluating news texts, the practices that produce them, or the conditions of their reception” (Carlson Citation2016, 353). Broadly, metajournalistic discourse can mean any discourse about or pertaining to journalism. Metajournalistic discourse matters because it shapes what journalism means to those who practice and consume it. It consequently not only reflects but constructs journalism’s authority and legitimacy, which do not simply “emerge” but must be discursively formalized and buttressed (Carlson Citation2016, Vos and Thomas Citation2018).

As a theoretical and methodological strategy, the analysis of metajournalistic discourse is premised on an understanding of discourse as organized language (visual or verbal) in service of meaning or, more simply, as active and “doing” something. As Carlson (Citation2016) puts it, “it is through metajournalistic discourse that the meanings of journalism are formed and transformed by actors inside and outside of journalism” (350). It follows that different actors use metajournalistic discourse for different purposes. It can be a discourse of insiders for insiders, such as can be found in trade publications like Columbia Journalism Review (see, e.g., Vos and Thomas Citation2018) or a discourse of insiders for outsiders, such as can be found in public-facing editorials and opinion columns when journalism is confronted with ethical crises and challenges to its legitimacy (see, e.g., Hindman and Thomas Citation2013). Such discourses tend to demonstrate how journalists police the boundaries and practices of their own field. However, it can also occur as a discourse of outsiders for insiders, such as in audience members’ evaluative online comments on journalistic practice (see, e.g., Craft, Vos, and Wolfgang Citation2016), or a discourse of outsiders for outsiders - that is, produced by people generally with no ties to journalism for an audience of people generally with no ties to journalism, as can be found in depictions of journalism in popular culture (see, e.g., Ehrlich and Saltzman Citation2015).

Visualizing Journalism and Journalists

In a visual context, we understand discourse to include both the site for social action and interaction as well as “a social construction of reality, a form of knowledge” (Fairclough Citation1995, 17-18). It can include a wide array of representations, such as photographs, title sequences in television, graphics for social causes, and, in this case, synthetic media. The investigation of these discourses ought to go beyond “identifying certain features or characteristics” to explore why these features exist, how they are produced, and what ideologies they advance (Aiello and Parry Citation2020, 11).

Much of the literature on metajournalistic discourse has focused on the construction of journalism and journalists via the written or spoken word, as found in news reporting, opinion columns, and the like. Journalism can also be visually constructed, of course. A particularly important body of work in this vein has been scholarship looking at the representation of journalists in popular culture. Scholars in this area emphasize the persuasive power of visual representations as “powerful tool[s] for thinking about what journalism is and should be” (Ehrlich and Saltzman Citation2015, 1). Popular culture portrayals of both journalistic virtue and journalistic vice reinforce notions of how journalism ought to be practiced, serving as teaching tools that encourage reflection on journalism’s role in society and on the efficacy and ethics of its practices (Ehrlich Citation2006, Citation2010; Ehrlich and Saltzman Citation2015; Feng Citation2022; Ferrucci Citation2018; McNair Citation2009).

Evaluations of popular culture depictions of journalism ought to attend to matters of professionalism, difference, power, and visuality itself (Ehrlich and Saltzman Citation2015). Regarding professionalism, scholars should examine the degree to which journalists are shown as seedy peddlers of sensationalized gossip or shown as more respectable professionals with training, credentials, and adherence to accepted ethical norms. Regarding the second consideration, difference, scholars should concern themselves with whether journalists are shown as aloof, elite, and disconnected from ordinary citizens or whether they are seen as blending into the crowd and being no different to anyone else. Regarding the third consideration, power, scholars should be attentive to journalists’ relationship to power and whether they are shown as holding power to account for the public good or are instead using power for personal gain. Regarding the fourth and final consideration, visuality itself, scholars should note the degree to which visual media (such as television news) focuses on infotainment and diversion at the expense of information and civic journalism. Here, the aspects of authenticity or accuracy, trivialization, and dehumanization are most salient (Thomson et al. Citation2022b).

The literature on depictions of journalists in popular culture skews significantly toward the study of visual media. The majority of this work has focused on how journalists have been rendered in movies (see, e.g., Ehrlich Citation2006, Citation2010; Feng Citation2022; McNair Citation2009) and on television shows (see, e.g., Ferrucci Citation2018; Ferrucci and Painter Citation2016, Citation2017; Painter Citation2017; Painter and Ferrucci Citation2017; Peters Citation2015), for example, with other visual forms such as comic books, cartoons, and advertisements attracting far less attention. AI-generated images provide an alternative and conceptually innovative way of studying the visual representation of journalists, not least because of how they complicate the notion of authorship in terms of who (or what) is doing the work of representing.

AI, Authorship, and Agency

A central assumption of metajournalistic discourse analysis, that discourse is active, draws our attention to the different actors involved and the motivations that drive their discourse. For example, a news organization’s ombudsman investigating reader complaints, an audience member commenting on a social media post of a news story, and a movie director making a film about journalistic malpractice will all, clearly, have different motivations and goals.

In this regard, the existing research on metajournalistic discourse can be said to represent the “key theoretical constant” in journalism studies (and communication studies generally) that “scholars have primarily defined communication as an activity between and among humans” (Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt Citation2019, 411). Artificial intelligence questions this understanding of communication because it removes the human-as-messenger framework that has been the foundation of communication research, complicating notions of agency and authorship (Guzman Citation2018; Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt Citation2019).

How, then, do we situate AI-generated images (or AI-generated content, broadly, for that matter) within the framework of metajournalistic discourse? One approach to this question is to note the human hand, so to speak, behind AI processes. This approach emphasizes how AI processes “are built through choices” (Culver and Minocher Citation2021, 328) as the algorithms that drive AI are, after all, “designed by people, and people embed their unconscious biases in algorithms” (Broussard Citation2018, 150). Overall, this perspective queries the notion that AI-generated images are truly without an “author.” A second approach would be to hold that the question of authorship is of less relevance than the question of how meaning is created in the interaction among humans and machines (Guzman Citation2018; Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt Citation2019). Scholars in this vein have argued that communication ought to be conceptualized holistically as the creation of meaning rather than being seen as synonymous with actor-centric human communication (Guzman Citation2018; Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt Citation2019). Without disagreeing with the first view, we believe the second provides the impetus for the investigation of interesting empirical questions. This is to say that taking the perspective of communication as the creation of meaning trains our attention on what meanings are made in AI-generated images, making them ripe for being read as “texts.”

Generative Art

Many people associate AI with “thinking” robots or computers capable of mimicking human reasoning and behavior, but this understanding is not entirely accurate. AI is a term that is often “haphazardly” invoked (Broussard et al. Citation2019, 673) but narrowly refers to a subfield of computer science that itself contains other subfields such as machine learning, expert systems, and natural language processing. AI is not capable of sentience but is “merely complex and beautiful mathematics” (Broussard et al. Citation2019, 677). Lewis defines machine learning within the AI field as “the training of a machine to learn from data, recognize patterns, and make subsequent judgments, with little to no human intervention” (in Broussard et al. Citation2019, 673).

Generative art refers to art “created when an artist cedes some degree of control to an autonomous system that creates, or is, the art” (Galanter Citation2019, 112). The history of generative and computer art began in the mid-1960s in Germany (Boden and Edmonds Citation2009). The evolution of computers in the subsequent decades and their increased processing power contributed to the development of generative art and the possibilities for what could be created and how. These forces were further enhanced through networked computers and Internet-connected devices which broadened the scope of what computers could do and how they function. Generative art, however, does not necessarily have to include a computer or digital technology, even though such features are common in today’s landscape. In this study, we operationalize “generative” art as images that are produced at least partly automatically by a piece of computer software. Boden and Edmonds (Citation2009) note that many terms such as generative art, computer art, digital art, computational art, and electronic art are used interchangeably and synonymously. However, others have tried to draw distinctions around these terms. For example, some scholars distinguish among interaction art, generative art, and robotic art though they also admit that these definitions are not fixed (see, e.g., Leggett Citation2000; Popper Citation2007). Notably, the above-mentioned problems of authorship and intent that span discussions about artificial intelligence are also germane concerns within debates about generative art (Galanter Citation2019).

We use generative art and synthetic media in this study to denote the partly automatic process of creation coupled with the acknowledgement that the creation is informed by a combination of components or elements (in this case, often-online image databases and corpora that the software draws on to respond to a text prompt). This study is concerned with Midjourney, one type of text-to-image software that is based on deep learning generative models (Oppenlaender Citation2022). Technical expertise is not a requirement to use this software and, as a result, this democratization of usage has led to an increase of users and outputs from Midjourney and similar platforms in recent years.

Making “art” or generating synthetic images in this case, is an iterative process. The user can tweak the command - known as “prompt engineering,” “prompt programming,” or “prompting” (Liu and Chilton Citation2022) and receive a subtly or markedly different result. The Midjourney interface itself also supports and enables this iterative process through providing users with an option to “upscale” the result in greater fidelity or to “remix” it and return additional variations without adjusting the text prompt.

Synthesis and Research Questions

The above research leads us to an understanding of metajournalistic discourse as spaces where meanings about journalism are constructed. One aspect of metajournalistic discourse analysis entails the examination of discourse that constructs the boundaries of who a journalist is, and what they do. Such boundaries can be shaped visually, as in the case of images of journalists in popular culture. Generative art – a form of art that draws on an algorithm to create images in response to user prompting – is an arena of discourse where meanings about what a journalist looks like may circulate, and is a hitherto unstudied area of metajournalistic discourse.

Understandings of journalism are typically examined in narrow and discrete ways, such as how specific types of journalists see themselves (Moon Citation2021; Willis Citation2009), how audience members perceive journalists (Rauch Citation2019), or how journalists are represented in a specific medium, such as film or television (Feng Citation2022; Ferrucci Citation2018). Exploring how AI “sees” journalism provides a unique perspective by combining genres, media, and conventions to present a composite view. This unique perspective is informed by a variety of sources, from movie frame grabs and cartoons to photojournalism and stock photography. By broadening the parameters we use to examine what is journalism and what a journalist looks like, we are treated to a rich thought experiment about who journalists are, how they work, and what relationships they have to others and to their environment. Doing so allows an examination of the convergence or divergence between AI vision and other social actors’ perceptions about journalism. Musing about how journalists and journalism are represented through AI can also provide insight on the blindspots and biases that journalists will encounter and potentially reproduce without awareness and conscientious control. This is increasingly important as news organizations and journalists begin integrating AI-generated images into their reporting processes (Grut Citation2022).

Our preliminary investigation into these images began with an examination of broad, “generic” terms that capture generic journalistic labels. Accordingly, we ask:

RQ1:How does the AI-enabled image generator Midjourney, as a proxy for broader collective consciousness, “see” the “generic” terms journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press?

RQ2:How does the AI-enabled image generator Midjourney, as a proxy for broader collective consciousness, “see” the “specialized” terms news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker?

RQ3:How stable or variable are the results (both in terms of what is represented and how) for the same keywords from RQs 1 and 2 when the generation process is repeated six months later?

Method

On August 14, 2022, we created a Midjourney account and began developing text prompts to create generative images through the software’s capabilities. To do this, the user joins a Discord server and enters a slash command in a bot channel (e.g.,/imagine prompt [text here]). For each text prompt, Midjourney, over the span of roughly 30-60 seconds, generates a series of four images in a 2 × 2 grid based on that prompt. Users then have the option of upscaling the image (increasing its resolution) or creating additional variations (that are “similar in overall style and composition to the image you selected”). Each generative prompt (including upscaling or creating variations) uses one of 25 free “jobs” for new accounts that, as of June 2023, do not expire but also do not renew. Midjourney also offers paid plans for those wishing additional features (such as renders that are privately rather than publicly visible) or additional “jobs” (that are used to create new renders, upscale them, or iterate on them through variations).

Midjourney allows users much flexibility in their commands, which then influences the resulting visual output. For example, a user could enter a generic and simple, one-word prompt like “flower” or a highly detailed and specific, multi-word prompt, like “a sunflower atop a hill in London amidst blowing snow at night with a dragon in the background.” However, this study is interested in seeing how AI “sees” a journalist and represents what they look like. As such, the text prompts for RQ1 were kept as generic as possible. We decided on four prompts: journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press.

The text prompts for RQ2 were developed with an intent to study the changing nature of specialized journalistic roles in the digital age. To identify the key words for this research question, we referred to five journalistic roles proposed by Weaver, Willnat, and Wilhoit (Citation2019). These include:

“Provide analysis of complex problems”

“Avoid stories with unverified content”

“Discuss national policy”

“Let people express their views”

“Provide entertainment”

We distilled each of these into a single keyword. For example, “Provide analysis of complex problems” became news analyst; “avoid stories with unverified content” became fact-checker; and “discuss national policy,” “let people express their views,” and “provide entertainment” became news commentator.

In order to study the stability or variability of results over time (for RQ3), as suggested by a peer reviewer, we generated in Midjourney an additional two rounds of image sets for the same seven keywords six months after generating the first. During this time, without warning and while the original study was under peer review, Midjourney released an upgrade to its algorithm (from v 3.0 to v 4.0).

Visual Social Semiotics

Visual social semiotics is a theoretical and analytical framework for “examining how images convey meaning” (Harrison Citation2003, 47). Its proponents argue that an image is a social process where meaning is negotiated between the creator and the viewer, and where social, cultural, political beliefs, values, and attitudes can influence the meaning that is made. Indeed, semiotic modes are shaped both by intrinsic qualities of the medium, the nature of machine learning and algorithmic vision, in this case, as well as by “histories and values of societies and their cultures” (Kress and van Leeuwen Citation2021, 20).

Kress and van Leeuwen (Citation2021) argue that an image performs three meta-semiotic tasks to create meaning. These include the representational metafunction, interpersonal metafunction, and compositional metafunction. They describe the interpersonal metafunction as about the actions among all the participants involved in creating and viewing an image. This includes the creator, those depicted, and the viewer. This metafunction answers the overall question, “How does the picture engage the viewer?”. It operates specifically through four features and processes, including image act and gaze; social distance and intimacy; and horizontal and vertical perspective.

Image act and gaze refers to the gaze of the person(s) depicted in relation to the viewer. A “demand” image act and gaze occurs when the person(s) depicted look directly at the viewer. Conversely, an “offer” image act and gaze occurs when the person(s) depicted look outside the frame or at someone or something within the image. The person(s) are shown more passively with this image act and are presented as an object of contemplation, leading to less engagement than with a “demand” image act.

Social distance and intimacy refers to how close the person(s) depicted are to the viewer, which connotes feelings of intimacy or distance. Harrison (Citation2003) defines six potential social distances, including intimate (where the head and face only are seen), close personal (where the head and shoulders are seen), far personal (where the figure[s] are seen from the waist up), close social (where the whole figure is seen), far social (where the whole figure with space around it is seen), and public (where torsos of several people are seen).

Horizontal perspective refers to the parallel or non-parallel positioning of the subject(s) in the frame relative to the viewer. When those who are observed are shown frontally to the viewer, this angle creates stronger engagement with the viewer and implies that the person(s) depicted are “one of us.” Conversely, when an oblique angle is used, this creates a sense of detachment and implies that the person(s) depicted are “one of them.”

Vertical perspective refers to either the vertical relationship between the person(s) depicted and the viewer or between or among the people depicted in the frame. The consideration here is of the meaning of angles, such as high viewing angles where the depicted person(s) are “looking up” which tend to show the person(s) depicted with less power. Medium-angle perspectives where the person(s) depicted are looking “horizontally” tend to show them with equal power to the viewer. Low-angle perspectives, where the person(s) depicted are looking down, tend to show them with greater power.

Process of Analysis

Analysis for the images generated in August 2022 (for RQ1 and 2) began in an inductive fashion through an open coding process (Parmeggiani Citation2009) where both members of the research team viewed the images generated from the defined prompts and noted salient aspects. Analysis continued in a deductive fashion informed by visual social semiotics (specifically the semiotic resources of image act/gaze, distance, and vertical and horizontal points of view) and previous literature about representations of journalists/journalism (specifically the sites of professionalism, difference, power, and visuality that Ehrlich and Saltzman [Citation2015] suggested). Each set of four images was analyzed individually and then all four image sets were also analyzed as a composite. In instances where potential ambiguity existed, the research team re-rendered specific prompts by “upscaling” them (which added both resolution and additional detail/clarity) so this ambiguity could be resolvedFootnote1.

Analysis for the images generated in February 2023 (for RQ3) began by placing the images (84) from all three generations onto a single screen, divided into columns by keyword, so that an appreciation could be achieved for how similar or dissimilar the results were over time. The images were then assessed column-by-column for what was depicted and then for how they were depicted to assess the stability or variability of algorithmic vision related to these terms.

Findings

Our analysis of the 16 images visualizing the four “generic” terms (journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press) identified certain consistent attributes. In nearly all of the images, the algorithm associated these terms with being a light-skinned, conservatively attired woman. Traces of digital technology were remarkably absent throughout these images. By contrast, the 12 images visualizing the three “specialized” terms (news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker) highlighted digital technologies much more prevalently and featured (older, light-skinned) men to a much greater degree. Overall, these images provide a rich foundation for analyzing and reflecting on who gets to be (or should be) a journalist doing which role(s), where, for whom, and with which tools. The sections that follow report our findings for the two research questions in turn.

Visualizing the Generic Journalist: Isolated, Female, and Urban

Our first research question probed how AI visualizes four seemingly generic terms: journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press. These are each analyzed and critically interpreted separately using a mix of visual social semiotic attributes and literature from the journalism studies canon.

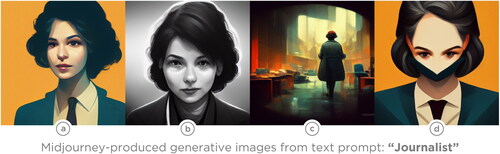

Algorithmically Seeing the “Journalist”

The first prompt, “journalist,” portrays the profession as an independent and isolating one (see ). The journalist is shown alone in each of the four renderings the AI process produced. Nowhere to be seen are the colleagues, such as camera operators, editors, or fixers, that are essential to the journalistic production process across outlets, contexts, and markets. Nowhere to be seen, either, are the sources on whom journalists rely for quotes, commentary, and expertise. In this view, the idea of the journalist as a one-person band is highlighted. The three head-on and tight head-and-shoulder shots (with even and flattering light against a plain background) in this grid are reminiscent of social media profile pictures and speak to how digital platforms have become essential to journalistic identity and to reporting practices (see Lough, Molyneux, and Holton Citation2018).

The journalist is shown as what appears to be a woman in all four images. When her face can be seen, she appears to be wearing lipstick and other makeup and to have medium-length, brushed hair. She is conventionally attractive and largely conservative in appearance. For example, there are no visible tattoos or piercings on what little of her (fair) skin can be seen. She wears full-length sleeves and a high-fitting (often collared) shirt that is sometimes accompanied by a necktie. While a woman wearing a necktie is not conventional - neckties are stereotypically and heteronormatively associated with a particular kind of conservative, conformist, white-collar masculinity (see Harris Citation2002) - it perhaps speaks to a vision of a professionalized journalist and as a white-collar worker who is comfortable in the echelons of power and comfortable interacting with elite sources that many Western news outlets (over)rely on (see Carlson Citation2009). The lighting in 1C suggests early morning or late evening and nods to the 24-hour nature of the job. What is most striking and perhaps disturbing is frame 1D, which appears to show the journalist without a mouth. The journalist’s nose is replaced with a beak-like point and, below this, a gaping black void. In this frame, the journalist appears to be looking down somewhat menacingly or at least in a determined fashion, at whatever lies in front of her.

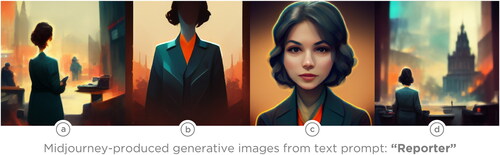

Algorithmically Seeing the “Reporter”

The second prompt, reporter, portrays the profession in a more collectivist and situated manner. The reporter figure, who still appears, as in , as a conventionally attractive, fair-skinned, and conservatively dressed woman, for the first time is shown interacting with people, or, at least, observing them (see ). In 2A, the reporter watches two other indistinct figures in the distance (the figures are in too great proximity to one another to have a conversation unless it was being shouted) and it appears that she has some sort of notebook in her hands she is using to document her observations.

The reporter appears to be outside or at least situated in proximity to an outdoor (urban) environment in three of the four renderings. In each of these three renderings, tall buildings with spires indicate that the reporter is based in an urban core within easy access to sources and sites of power. Indeed, the final rendering (2D) with its grand stature and stories of columned facades suggests a government building, such as a parliament or state house. The reporter is oriented toward this building, suggesting that she is engaging in the watchdog function of journalism and, by her presence, proactively keeping government (and power, more broadly) to account. Her business clothes in these renderings are typical in an urban environment; however, she is wearing a distinctive shade of orange underneath her jacket, which is visible in the two frames (2B and 2C) where she is facing the viewer. This shade of orange is reminiscent of safety vests that are worn in highly regulated professions such as law enforcement and construction. Visually invoking a safety vest using this color invites multiple interpretations. On one hand, it could be that the reporter - by virtue of their accountability function - is a symbol and personification of safety and good governance. Conversely, needing to wear highly visible colors associated with safety can speak to the vulnerabilities that journalists face as targets for harassment, abuse, and violence, a problem that is particularly chronic for women journalists (see Chen et al. Citation2020; Miller and Lewis Citation2022).

In contrast to (of the journalist), the audience only sees the reporter’s face in one of the four frames. AI showed the journalist as being more public-facing in the bulk of the renderings, while it rendered the reporter as being oriented away from the viewer and toward power more often.

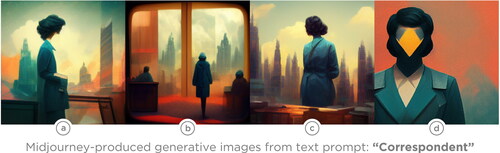

Algorithmically Seeing the “Correspondent”

The third prompt, correspondent, continues the trend started in of showing the figure, who throughout all the renders so far, appears to be wearing the same blue jacket and to have the same dark and wavy hair, situated in an urban location (see ). She is once again shown in the bulk of the renders amidst towering skyscrapers and appears in frame 3A to once again hold either some sort of notebook or book. The beak-like facial feature from 1D (of the journalist) returns in frame 3D but this time, and across all four renders, the figure’s facial features are completely obscured. She appears to be facing away from the viewer in two frames, facing to the side in one frame, and, in the one frame where she is facing the viewer, appears to be wearing an orange covering that shields her facial features. This mask or visor suggests protection from a harsh environment or a nod to a post-human future where some sort of stylized virtual or augmented mask can enhance the wearer’s vision and abilities. If this latter interpretation is correct, it would be the first instance of digital technology represented in the sample so far. Reflecting upon all four frames, the figure is largely shown as isolated in the perhaps foreign environment. In only one frame is the correspondent shown with others and, even then, they are shown at a distance rather than being engaged in conversation at close proximity. The figure’s horizontal positioning in the bulk of these frames suggests the correspondent is “one of them” rather than “one of us,” further reinforcing the notion of difference and otherness.

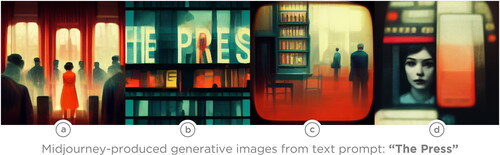

Algorithmically Seeing “the Press”

The fourth and final of the prompts analyzed for RQ1, “the press,” bucks previous trends as these are the first renders to, in some instances, not show people, or to show them in mediated fashion only (see ). In the first frame (4A), the journalist is either shown as being hyper-visible in a striking red dress surrounded by a sea of drably attired figures or the sea of shadowy figures is instead the press and the hyper-visible character in the center is some high-status individual that contrasts markedly with those around her. In either case, this frame is the first to show a more dynamic interaction between the press and those it covers. In contrast to earlier renderings that showed the journalist primarily observing others from the periphery, it appears in this frame that a verbal exchange is taking place, perhaps through the form of a press conference. In the second frame (4B), large letters appear that spell out “the press” but the letters aren’t rendered crisply. They are somewhat hazy and appear in places to be duplicated and overlaid on top of one another, similar to how someone who is intoxicated might see the letterforms. The letterforms themselves are nearly all uniformly pure cream-colored except for the letter “R” which appears to be discolored with streaks of red. This marked shift in color hints at the “If it bleeds, it leads” mantra that is frequently associated with the “conflict” news value in journalism (see Miller and Albert Citation2015).

The subtle reference to alcohol that is present in 4B is repeated more explicitly in 4C. In this frame, bottles (presumably of alcohol) sit in rows on shelves next to two figures. This might again be an attempt to associate journalists with alcoholism or, more generously, as a nod to the public spaces, such as cafes and pubs, at which journalists frequently meet their sources or find story ideas. In the final frame of this render, we see presumably the same woman’s face as from previous renders but here she appears to be mediated by some digital technology. It appears that the woman’s face appears on the rear viewfinder of a digital camera or on some other digital interface, such as a screen within a television control room. In contrast to other renders where the figure’s facial features are identifiable (1A, 1B, 1D, and 2C), the woman’s features here appear dark, and the lighting makes her features look foreboding.

Visualizing the Specialized Journalist: Older, Male, and Digital

The second research question probed how AI visualizes three “specialized” journalistic roles: news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker. Like with the first research question, these terms, too, are each analyzed and critically interpreted separately using a mix of visual social semiotic attributes and literature from the journalism studies canon.

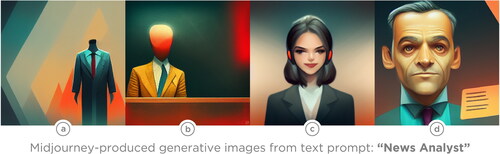

Algorithmically Seeing the “News Analyst”

The first prompt of the specialized roles, news analyst, uniformly shows this as a white-collar profession (see ). Indeed, each of the four people who are shown as news analysts wear a white-collared shirt, three with accompanying necktie, and all four also wear a sports jacket or blazer. We are treated in the final frame (5D) to the first image of a man in the sample. Interestingly, the AI algorithm rendered all the non-specialised roles as being occupied by women, but the first of the specialized roles is shown being occupied by both women and men. In contrast to the early renderings which also featured a jacket but one that was more military style, the sports jackets here are all more business in style and reflect a perhaps more affluent and professional vibe. Two of the four figures in this render are either missing their head entirely or are shown with a smooth orb for a head that lacks identifying features or common landmarks, such as eyes, a nose, or a mouth. This perhaps speaks to the impersonal and behind-the-scenes nature of analysis. The people here are not necessarily the presenters and broadcasters who are reporting the news directly to audiences; rather, they are tucked away in offices crunching data and trying to make sense of it. For these reasons, the facial features of the figures are perhaps not as prominent as they represent often-invisible labor.

Algorithmically Seeing the “News Commentator”

The second prompt of the specialized roles, news commentator, continues the trend started with the news analyst role in depicting this occupation as white collar and sports jacket-wearing (see ). With this specialized role, there is finally some digital technology more overtly present in the form of two microphones that the figures in frames 6C and 6D wear or sit in front of. The idea of spectacle is present across all four renders. In the first frame (6A), the figure appears grotesque and surrealist with oversized ears, deep-set eyes, and impossibly high eyebrows. The eyes, the so-called windows into the soul, appear shut indicating that the person is of questionable character and is not making a direct connection with the audience through gaze. In the second frame (6B), the figure has bug eyes that seem to indicate a thirst for sensational content and for the infotainment that has come to be associated with television (see Brants Citation2008). Indeed, the figure here appears to be seen through a grainy screen (grain being an indication of the fuzziness of truth or the blending of truth and fiction) and shown in black and white as a nod to a distant past. This perhaps indicates that news commentary is better seen as a relic from a far-gone time than a practice that should be continued in the digital era.

In frames 6C and 6D, we see a silver-haired man in studio lighting with lower-thirds on the bottom of the frame to indicate personal or organizational branding and context. It is interesting to reflect that the news commentator appears wrinkled in all four renders and to ponder the implicit assumption that only older (white) men have thoughts worth sharing in public. Interesting, too, is that only the men are “allowed” to have wrinkles and be in front of cameras. None of the previous renderings of women show them with wrinkles, which speaks to the double standard related to gender and age that exists in the real world (see Harrison Citation2019) and is replicated through algorithmic vision.

Algorithmically Seeing the “Fact-Checker”

The third and final prompt of the specialized roles, fact-checker, is interesting for its almost complete lack of human presence (see ). Much of real-time content moderation is performed by algorithms and computer vision (Gorwa, Binns, and Katzenbach Citation2020) but it is interesting to see this interpretation carried through to fact-checking, as well. Journalism has been described as a discipline of verification (Kovach and Rosenstiel Citation2014) and while computers can assist with these efforts, the way this concept is algorithmically portrayed is striking. In the first frame (7A), the viewer is treated to a grayscale image which shows the sole human element of these renders, indicating perhaps that human fact-checking is in the minority or at least is incomplete without tools and (digital) technologies. Here, the person’s identity is less important than their role in the process. They often represent some organization which takes center stage in arbitrating whether a claim is “true” or “false.” Indeed, in the second frame (7B), the viewer appears to be presented with some sort of fact-checking display which presumably will flash red when a false claim is detected and blue-green when a true claim is detected. The underlying logic that truth is a binary true-false dichotomy is, however, disrupted in the adjacent frame (7 C) where black and white are shown next to a gradient from light to dark. As Wardle (Citation2018) and others have argued, truth exists on a continuum where misleading or false claims can exist alongside truthful or accurate elements. This render appears to represent that reality. The final rendering (7D) seems to represent, with hundreds or thousands of boxes, the number of truth claims that one encounters every day. The rendering appears to be a stylized data visualization showing some kind of bar chart representing volume and time, which are two key contributing factors to mis- and disinformation’s spread (Thomson et al. Citation2022a).

Visualizing Similarities and Differences over Time

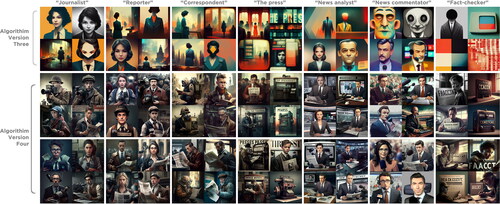

The study’s third research question explored how enduring or variable is algorithmic vision over a six-month period of time. As can be seen in , the visual style of the second and third round of image generations for these seven keywords is markedly different to the style employed in the first generations. This difference is likely due to the algorithmic upgrade that occurred between version 3.0 that was used in August 2022 to generate the initial images and version 4.0 that was used in February 2023 to generate the second and third sets of images.

Despite the differences in visual style for the same keywords without any additional “prompt engineering” (Liu and Chilton Citation2022), several content features and attributes remain constant. For example, all the images across the three iterations exclusively feature light-skinned people. Gender disparities persisted, too, across the renderings for the more specialised terms (news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker), which featured men in 89% of all cases. Gender diversity, however, was more equal for the generic terms across the three iterations. Here, men accounted for 57.5% of the main subjects represented. The figures throughout the sample remain conservatively attired, wear and color their hair in conventional ways, and display no sign of tattoos or piercings. The gender-age disparity also persists. No older women are shown and only men are shown with wrinkles and other signs of age (such as graying, receding, or white hair). The figures shown are also nearly uniformly serious or neutral in their expressions. Only three journalists (two women and one man, out of more than 60 individuals) are shown smiling.

Despite the above persistent features and attributes, the newer iterations also display interesting differences. For example, the generations from February 2023 are the first in the sample to depict youth. These two youths (both boys) are depicted in the fact-checker column and interestingly, both appear to have bruised and or bloodied faces. This may suggest a conflict or war over truth and that the effects of mis/disinformation can be physically harmful. It interestingly also shows the recipients of this harm as being the next generation in the form of two young males. Visual depictions of legacy print media are also more pronounced in the newer images from the generic keywords (journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press). Figures holding printed newspapers abound and there are no fewer than five printing presses shown in addition to a typewriter.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study looks at a novel site of visual metajournalistic discourse: AI-generated images of a variety of different journalistic roles. Following others (see Guzman Citation2018; Lewis, Guzman, and Schmidt Citation2019), we see AI content as an important and burgeoning source of meaning-making ripe for scholarly analysis, thus connecting this area of literature to two others, namely the study of metajournalistic discourse generally and the literature on visual depictions of journalism, hitherto dominated by studies looking at how journalists have been represented in movies and on television shows. AI-generated images provide insight into questions around the sociocultural construction of journalism because of the unique way they reveal biases and implicit assumptions of and by those who capture or commission images and those who decide which images and processes inform machine learning and machine vision, thereby influencing the resulting generative images that AI produces. Our study focused on the analysis of two distinct groups of terms: (1) A set of “generic” terms, namely journalist, reporter, correspondent, and the press; and (2) A set of “specialized” terms of growing interest to journalism studies scholars, namely news analyst, news commentator, and fact-checker.

Agency, Awareness, and Encoding

Many images in popular culture are the result of conscientious decisions. Some decisions are made through intuition or without advanced planning but others, especially by professionals, are strategically made for aesthetic, storytelling, or ideological reasons (Kobré Citation2017). With AI-generated imagery, however, the user is partly removed from this encoding process when generic terms are used and AI is left to fill in the blanks. For example, when a user inputs a generic command like “imagine/person on a hill,” AI is left to determine the person’s age, ethnic background, gender, class, attire, and other attributes. This can perpetuate or disrupt stereotypes and can do so in confounding ways due to the lack of transparency around how the algorithms regulating text-to-image generators work.

Reproducing and Disrupting Biases

In some ways, AI reinforces existing biases and inequities present in journalism and its representation in popular culture: for example, in the double standards applied to women that are not applied to men in newsrooms (Harrison Citation2019) and in the lack of racial diversity and the ageism reflected in who AI suggests is fit to be a journalist. In other ways, AI provides food for thought in reflecting on the social construction of journalism. For example, the extreme ages shown in the fact-checker prompt provide fascinating provocations about the realities of fact-checking in the digital environment. Two older men with pure white hair are seen here engaged in the act of fact-checking, which suggests that one could spend a lifetime trying to evaluate and counter the myriad claims, half-truths, and downright lies one encounters online. It also, by showing the opposite end of this age spectrum, makes us aware of how susceptible youth are to the influence of truth claims online and how these claims have the potential to inflict real and lasting damage.

Implications and Directions for Further Study

These AI-generated visions of journalism, and others like them, risk perpetuating existing inequalities related to gender, ethnic background, and age. Across global contexts, women are overrepresented in university journalism courses and in rank-and-file journalism positions but are under-represented in management and senior roles (see, e.g., Boateng Citation2017; Steiner Citation2020). They are also more likely to have their emotional displays policed compared to men (Thomson Citation2021). Likewise, journalists tend to under-represent, trivialize, or condemn older people in their coverage and are also at-risk of incorporating racial biases into their reporting (Marotta, Howard, and Sommers Citation2019; Thomson et al. Citation2022b). These same disparities and biases seem to sadly be reflected in AI visualizations of journalism. It is particularly interesting to note the lack of older women compared to older men and to compare the gender distribution between the “generic” and “specialized” roles. The uneven representation of women in the ranks of more specialized and tech-driven areas of journalism (see Usher Citation2019), as illustrated (literally) here, warrants further analysis.

Relatedly, the dominance of men in the AI renders of “analysts” and “commentators” should cause some reflection. The algorithmic visions studied here suggest that men have the status that comes with a license to “analyze” and “comment” (in other words, to opine), while distinctly analog women are relegated to more routine forms of journalism. The role of opinion in journalism, and opinion journalism roles (e.g., analyst, commentator, columnist) particularly, remain under-studied in journalism scholarship (Kelling and Thomas Citation2018) so the gendered dimensions of these roles and the apparent dominance of “mansplainers” in this subfield (see Koc-Michalska et al. Citation2021) warrant further study.

This study analyzed four “generic” terms and three “specialized” ones but there are obviously more ways to describe journalism and journalists that aren’t captured by these terms. Future research could expand on these initial terms by comparing and contrasting them with other ones. Alternatively, this analysis could be done longitudinally to see how AI understandings of these terms change or evolve over longer periods of time. Another approach that should be investigated is the degree to which the same terms produce similar or dissimilar results from different AI generation sites, like DALL-E 2 or NightCafe Creator. Additional attributes beyond the nouns used in this study could also be used to see how AI visualizes journalists and journalism in different national-global contexts (e.g., Chinese journalists compared to American journalists). Subsequent studies should continue to explore the role of AI and other automatic decision-making processes in helping to shape the discourse around journalism and journalists so that a robust and evolving conversation around this important institution can continue into the future.

It is worth pondering what happens to AI-generated image sets after being generated and what implications this has for journalism practice and scholarship. Midjourney defines itself as an “open-by-default” community. This means that, for most users, the images they generate—including those using private Discord servers or via direct messages—are visible at midjourney.com (Midjourney does, however, offer a “stealth mode” for the highest subscription tier ($60/month, as at March 2023, which provides privacy for generated images). This open-by-default approach, however, means that the vast majority of the images generated are publicly viewable (and also able to be remixed and adapted by others). Images generated during the Midjourney free trial bear a CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which allows the images to be freely shared and transformed. All of Midjourney’s paid options allow for commercial use of the resulting generations. Thus the images generated on sites like Midjourney have high visibility within the site-specific community and also can enjoy greater visibility when they are circulated in the public sphere. This is the case for news organizations and journalists who are already using services like Midjourney to illustrate their news products and articles (The Economist Citation2022; Warzel Citation2022). Along with this greater visibility is the necessity for scholarly study and industry guidance to ensure that these practices are appropriately used. Indeed, The Nieman Journalism Lab, funded by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, identified in 2023 a “pressing need” for both “rules and guidelines for creating or using AI-generated content” and “a broader review of how images are treated by the news media” (Grut Citation2022). Newsrooms would do well to consider and provide guidance on the use of AI-generated images in their news products. Likewise, researchers would be wise to study existing practices, attitudes, and effects related to AI imagery in news.

Limitations

At face value, selecting 84 “texts” for analysis might seem like a small sample size. However, visuals are incredibly rich sites for analysis and entire journal articles and books (see, e.g., Albee and Freeman Citation1995; Hariman and Lucaites Citation2002) have been written on single images. We therefore argue that, for a nascent topic like understanding journalistic roles through AI-generated imagery, the sample is more than sufficient. Our shared theoretical and epistemological orientation is interpretivist and thus, inherently subjective. However, despite the subjectivity of our positioning, the systematic method of coding and analysis we deployed, informed by a deep engagement with the relevant literature, makes a contribution to understanding how visual discourse can contribute to our understanding of what journalism is and who is (or should be) a journalist, as well as to how metajournalistic discourse can operate with varying degrees of agency. There is an inherent opaqueness to many digital processes and platforms (Suzor Citation2019) and Midjourney is no exception. It lacks published documentation about the source of the image libraries its software uses to create images and without it, a sense of how national or international these sources are, as well as context about their other attributes.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 For example, 3A was upscaled to provide clarity on what the figure was holding, 3D was upscaled to provide more clarity on the face area and whether this was, in fact, a mask or visor, and 4C was upscaled to provide more clarity on whether the objects on the shelves were books or bottles.

References

- Aiello, G., and K. Parry. 2020. Visual Communication: Understanding Images in Media Culture. London: Sage.

- Albee, P. B., and K. C. Freeman. 1995. Shadow of Suribachi: Raising the Flags on Iwo Jima. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Boateng, K. J. 2017. “Reversal of Gender Disparity in Journalism Education-Study of Ghana Institute of Journalism.” Observatorio (OBS*) 11 (2): 118–135. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS11220171019

- Boden, M. A., and E. A. Edmonds. 2009. “What is Generative Art?” Digital Creativity 20 (1-2): 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626260902867915

- Brants, K. 2008. “Infotainment.” In Encyclopedia of Political Communication, edited by L. L. Kaid and C. Holtz-Bacha, 336). Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Sage.

- Broussard, M. 2018. Artificial Unintelligence: How Computers Misunderstand the World. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Broussard, M., N. Diakopoulos, A. L. Guzman, R. Abebe, M. Dupagne, and C. H. Chuan. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence and Journalism.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (3): 673–695. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019859901

- Carlson, M. 2009. “Dueling, Dancing, or Dominating? Journalists and Their Sources.” Sociology Compass 3 (4): 526–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00219.x

- Carlson, M. 2016. “Metajournalistic Discourse and the Meanings of Journalism: Definitional Control, Boundary Work, and Legitimation.” Communication Theory 26 (4): 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12088

- Chen, G. M., P. Pain, V. Y. Chen, M. Mekelburg, N. Springer, and F. Troger. 2020. “You Really Have to Have a Thick Skin”: a Cross-Cultural Perspective on How Online Harassment Influences Female Journalists.” Journalism 21 (7): 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918768500

- Coleman, R. 2010. “Framing the Pictures in Our Heads: Exploring the Framing and Agenda-Setting Effects of Visual Images.” In Doing Frame Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives, edited by P. D’Angelo and J. A. Kuypers, 233–261. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Craft, S., T. P. Vos, and J. D. Wolfgang. 2016. “Reader Comments as Press Criticism: Implications for the Journalistic Field.” Journalism 17 (6): 677–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915579332

- Culver, K. B., and X. Minocher. 2021. “Algorithmic News: Ethical Implications of Bias in Artificial Intelligence in Journalism.” In The Routledge Companion to Journalism Ethics, edited by L. T. Price, K. Sanders, and W. N. Wyatt, 328–336. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- The Economist. 2022. How a computer designed this week’s cover. https://www.economist.com/news/2022/06/11/how-a-computer-designed-this-weeks-cover

- Ehrlich, M. C. 2006. “Facts, Truth, and Bad Journalists in the Movies.” Journalism 7 (4): 501–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884906068364

- Ehrlich, M. C. 2010. Journalism in the Movies. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Ehrlich, M. C., and J. Saltzman. 2015. Heroes and Scoundrels: The Image of the Journalist in Popular Culture. Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Fairclough, N. 1995. Media Discourse. London: Arnold.

- Feng, Y. 2022. “Spotlight”: Virtuous Journalism in Practice.” Journal of Media Ethics 37 (2): 93–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/23736992.2022.2057996

- Ferrucci, P. 2018. “Mo “Meta” Blues: How Popular Culture Can Act as Metajournalistic Discourse.” International Journal of Communication 12: 4821–4838. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/8550.

- Ferrucci, P., and C. Painter. 2016. “Market Matters: How Market Driven is the Newsroom?” Critical Studies in Television: The International Journal of Television Studies 11 (1): 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749602015618633

- Ferrucci, P., and C. Painter. 2017. “Print versus Digital: How Medium Matters on House of Cards.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 41 (2): 124–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0196859917690533

- Galanter, P. 2019. “Artificial Intelligence and Problems in Generative Art Theory.” Proceedings of EVA London 2019. https://doi.org/10.14236/ewic/EVA2019.22

- Gorwa, R., R. Binns, and C. Katzenbach. 2020. “Algorithmic Content Moderation: Technical and Political Challenges in the Automation of Platform Governance.” Big Data & Society 7 (1): 205395171989794. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951719897945

- Grut, S. 2022. “Your Newsroom Experiences a Midjourney-Gate, Too.” NeimanLab niemanlab.org/2022/12/your-newsroom-experiences-a-midjourney-gate-too/.

- Guzman, A. L. 2018. “What is Human-Machine Communication, Anyway?.” In Human-Machine Communication: Rethinking Communication, Technology, and Ourselves, edited by A. L. Guzman, 1–28. New York, USA: Peter Lang.

- Hariman, R., and J. L. Lucaites. 2002. “Performing Civic Identity: The Iconic Photograph of the Flag Raising on Iwo Jima.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 88 (4): 363–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630209384385

- Harris, D. 2002. “Neckties.” The American Scholar 71 (2): 79–84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41213296.

- Harrison, C. 2003. “Visual Social Semiotics: Understanding How Still Images Make Meaning.” Technical Communication 50 (1): 46–60. https://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/stc/tc/2003/00000050/00000001/art00007.

- Harrison, G. 2019. “We Want to See You Sex It up and Be Slutty:” Post-Feminism and Sports Media’s Appearance Double Standard.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 36 (2): 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2019.1566628

- Hindman, E. B., and R. J. Thomas. 2013. “Journalism’s “Crazy Old Aunt”: Helen Thomas and Paradigm Repair.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 90 (2): 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699013482909

- Johnston, J., and A. Wallace. 2017. “Who is a Journalist? Changing Legal Definitions in a Deterritorialized Media Space.” Digital Journalism 5 (7): 850–867. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1196592

- Kelling, K., and R. J. Thomas. 2018. “The Roles and Functions of Opinion Journalists.” Newspaper Research Journal 39 (4): 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532918806899

- Kobré, K. 2017. Photojournalism: The Professionals’ Approach. 7th ed. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Koc-Michalska, K., A. Schiffrin, A. Lopez, S. Boulianne, and B. Bimber. 2021. “From Online Political Posting to Mansplaining: The Gender Gap and Social Media in Political Discussion.” Social Science Computer Review 39 (2): 197–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319870259

- Kovach, B., and T. Rosenstiel. 2014. The Elements of Journalism: What Newspeople Should Know and the Public Should Expect. 3rd ed. New York, USA: Three Rivers Press.

- Kress, G., and T. van Leeuwen. 2021. Reading Images: The Grammar of Visual Design. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Leggett, M. 2000. “Thinking Imaging Software.” Photofile 60: 26–29. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.200100603.

- Lewis, S. C., K. Kaufhold, and D. L. Lasorsa. 2010. “Thinking about Citizen Journalism: The Philosophical and Practical Challenges of User-Generated Content for Community Newspapers.” Journalism Practice 4 (2): 163–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700903156919

- Lewis, S. C., A. L. Guzman, and T. R. Schmidt. 2019. “Automation, Journalism, and Human–Machine Communication: Rethinking Roles and Relationships of Humans and Machines in News.” Digital Journalism 7 (4): 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1577147

- Liu, V., and L. B. Chilton. 2022. “Design Guidelines for Prompt Engineering Text-to-Image Generative Models.” Proceedings of the 2022 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1145/3491102.3501825

- Lough, K., L. Molyneux, and A. E. Holton. 2018. “A Clearer Picture: Journalistic Identity Practices in Words and Images on Twitter.” Journalism Practice 12 (10): 1277–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1389292

- Marotta, S. A., S. Howard, and S. R. Sommers. 2019. “Examining Implicit Racial Bias in Journalism.” In Reporting Inequality: Tools and Methods for Covering Race and Ethnicity, edited by S. Lehrman and V. Wagner, 66–81). Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- McNair, B. 2009. Journalists in Film: Heroes and Villains. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

- Miller, K. C., and S. C. Lewis. 2022. “Journalists, Harassment, and Emotional Labor: The Case of Women in on-Air Roles at U.S. local Television Stations.” Journalism 23 (1): 79–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919899016

- Miller, R. A., and Albert, K. 2015. “If It Leads, It Bleeds (and If It Bleeds, It Leads): Media Coverage and Fatalities in Militarized Interstate Disputes.” Political Communication 32 (1): 61–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.880976

- Moon, R. 2021. “When Journalists See Themselves as Villains: The Power of Negative Discourse.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 98 (3): 790–807. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699020985465

- Oppenlaender, J. 2022. The creativity of text-to-image generation. ArXiv. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2206.02904.pdf https://doi.org/10.1145/3569219.3569352

- Painter, C. 2017. “All in the Game: Communitarianism and the Wire.” Journalism Studies 18 (1): 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2016.1215253

- Painter, C., and P. Ferrucci. 2017. “Gender Games: The Portrayal of Female Journalists on House of Cards.” Journalism Practice 11 (4): 493–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1133251

- Parmeggiani, P. 2009. “Going Digital: Using New Technologies in Visual Sociology.” Visual Studies 24 (1): 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14725860902732991

- Peters, C. 2015. “Evaluating Journalism through Popular Culture: HBO’s the Newsroom and Public Reflections on the State of the News Media.” Media, Culture, & Society 37 (4): 602–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443714566902

- Popper, F. 2007. From Technological to Virtual Art. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Rauch, J. 2019. “Comparing Progressive and Conservative Audiences for Alternative Media and Their Attitudes towards Journalism.” In Alternative Media Meets Mainstream Politics: Activist Nation Rising, edited by J. D. Atkinson and L. Kenix, 19–38. Blue Ridge Summit, PA: Lexington.

- Steiner, L. 2020. “Gender, Sex, and Newsroom Culture.” In The Handbook of Journalism Studies, edited by K. Wahl-Jorgensen and T. Hanitzsch, 2nd ed., 452–468). Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Suzor, N. P. 2019. Lawless: The Secret Rules That Govern Our Digital Lives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomson, T. J. 2021. “Mapping the Emotional Labor and Work of Visual Journalism.” Journalism 22 (4): 956–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918799227

- Thomson, T. J., D. Angus, P. Dootson, E. Hurcombe, and A. Smith. 2022a. “Visual Mis/Disinformation in Journalism and Public Communications: Current Verification Practices, Challenges, and Future Opportunities.” Journalism Practice 16 (5): 938–962. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1832139

- Thomson, T. J., E. Miller, S. Holland-Batt, J. Seevinck, and S. Regi. 2022b. “Visibility and Invisibility in the Aged Care Sector: Visual Representation in Australian News from 2018–2021.” Media International Australia. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X221094374

- Ugland, E., and J. Henderson. 2007. “Who is a Journalist and Why Does It Matter? Disentangling the Legal and Ethical Arguments.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 22 (4): 241–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/08900520701583511

- Usher, N. 2019. “Women and Technology in the Newsroom: Vision or Reality from Data Journalism to the News Startup Era.” In Journalism, Gender, and Power, edited by C. Carter, L. Steiner, and S. Allan, 18–32. Milton Park, UK: Routledge.

- Vos, T. P., and R. J. Thomas. 2018. “The Discursive Construction of Journalistic Authority in a Post-Truth Age.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 2001–2010. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1492879

- Wardle, C. 2018. “The Need for Smarter Definitions and Practical, Timely Empirical Research on Information Disorder.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 951–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1502047

- Warzel, C. 2022. Where does Alex Jones go from here? The Atlantic. https://newsletters.theatlantic.com/galaxy-brain/62f28a6bbcbd490021af2db4/where-does-alex-jones-go-from-here/

- Weaver, D. H., L. Willnat, and G. C. Wilhoit. 2019. “The American Journalist in the Digital Age: Another Look at U.S. news People.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96 (1): 101–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699018778242

- Willis, J. 2009. The Mind of a Journalist: How Reporters View Themselves, Their World, and Their Craft. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Sage.