Abstract

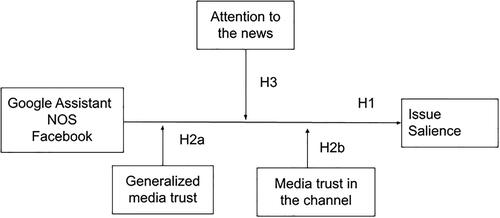

The emerging use of Conversational Agents (CAs), such as Google Assistant, highlights the role of algorithmic gatekeeping power in news consumption. However, our knowledge of the effects of CAs on shaping the public’s perception of the most important topics (issue salience) is limited. To investigate this, we conducted a seven-day longitudinal survey in the Netherlands, comparing the most important issues reported by users (N = 352) across various channels, including CAs, social media, and news websites. Our aim was to analyze how CAs influence the transfer of issue salience from the channel to the user. While our hypotheses were not supported, different patterns emerged. Users consuming news through CAs exhibited a have a lower probability of agreeing on the most important issues in the Netherlands compared to participants consuming information on social media and news websites. This suggests that news consumption through CAs may offer less shared context compared to other channels. Furthermore, trust in the channel and attention to the news were found to be significant predictors of agreement on issue salience. These findings raise important questions for further research, particularly regarding the impact and democratic role of CAs within the broader news ecosystem.

Introduction

The shift to audio news consumption has been mainly driven by the popularity of conversational agents (CAs) at home, such as Google Assistant, Alexa, and Siri (Newman Citation2022). Although news consumption via CAs is still emerging, one in every five users asks CAs for news regularly, and the numbers are expected to rise in the upcoming years (Newman Citation2018). In countries where there is a high level of technology adoption, such as the Netherlands, the developments of voice technologies are continuously evolving suggesting a boost for more audio-based interfaces in the near future (NPO Citation2021). However, the adoption of CAs for news consumption can amplify the challenges within the media ecosystem such as the control of algorithms over information flows that shape our social realities (Diakopoulos Citation2019).

Traditionally, news organizations were known as news gatekeepers, as they had control over the information flows that reached the public. However, in today’s complex media diets, individuals encounter multiple information sources, such as news websites, social media and CAs (Vermeer et al. Citation2020). The access to some of these information flows (e.g., social media and CAs) is mostly dominated by algorithms and the institutions behind them with worldwide companies such as Meta, Google (Google Assistant), Amazon (Alexa), and Apple (Siri) (Diakopoulos Citation2019). The control over information flows represents a political power that can influence the opinion formation process (Helberger Citation2020), because news coverage can affect public issue salience (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Trenaman and McQuail Citation1961). Public issue salience is a relevant notion for societies, as it helps to shape public policies to address the most important problems (Paul and Fitzgerald Citation2021). The transference of issue salience is contingent on two important variables: media trust and attention. Media trust increases exposure and acceptance of information (Kalogeropoulos, Suiter, and Eisenegger Citation2019), while attention is a critical variable that can influence the processing of information (Chaffee and Schleuder Citation1986).

CAs, in particular, extend the possibilities of news consumption by offering voice interactions, making it important to understand their role in relation to issue salience, trust, and attention. When asking CAs for news, the system providers have knowledge of the individual to recommend the information that should be consumed (Gannes Citation2019). This situation can potentially worsen the conditions for sharing a common context. If the public does not share the same information; it is challenging to find a shared knowledge agreeing on important societal topics for addressing them with public policies (Bodó et al. Citation2019).

Emerging research has examined the quality of the information provided by CAs, such as Amazon’s Alexa (Dambanemuya and Diakopoulos Citation2020). Others have tested the effects on opinion ambivalence and positive journalism of news distributed through chatbots and smart speakers (Jones and Jones Citation2019; Zarouali et al. Citation2021). However, until now, there is a lack of empirical evidence on the perceptions of individuals in public issue salience when using a CA for news consumption. By theorizing the influence of a CA (Google Assistant) on public issue salience, we extend research on news aggregators and public issue salience (Dennison Citation2019; Paul and Fitzgerald Citation2021; Shehata and Strömbäck Citation2013). To do so, we compare the influence of Google Assistant with two of the most common channels for news consumption in the Netherlands: social media (Facebook) and a regular Dutch news site (NOS). Our approach relies on a seven-day longitudinal survey asking users about the most important issue found in the news. To guide the research, focusing on identifying the influence of CAs, we propose the following question:

RQ: How do conversational agents influence issue salience?

Public Issue Salience Transference

The conceptualization of public issue salience varies, but it mainly refers to "the degree to which a person is passionately concerned about and personally invested in an attitude" (Krosnick Citation1990). Individuals can differ on the degree of importance of each issue (Paul and Fitzgerald Citation2021). As everyone has their own prioritized events or topics, we conceptualize issue sets as the current events and topics that create an agenda for each individual (Wanta and Ghanem Citation2007). In the context of this study, we define public issue salience as the set of topics that an individual considers important in the present, while we call issue salience agreement to the alignment of issues sets between the individual and other news consumers (i.e., the consensus of issue salience).

A central assumption for issue salience is that individuals learn from the media to acquire a shared knowledge of the events happening around them (Shehata and Strömbäck Citation2013; Su and Li Citation2021). However, since each channel differs in the selection of prominent topics (Shehata and Strömbäck Citation2013), individuals may also have different prioritization of issues according to their preferred channel for news consumption.

In today’s fragmented media environment, individuals access information through multiple means such as CAs, news websites, and social media (Vermeer et al. Citation2020). Additionally, since news organizations are pressed to capture new audiences, multiple media companies rely on social media and CAs as new ways of interacting with their public. However, many of these channels have algorithmically curated information flows driven by third-party platforms. Thus, as individuals learn from the news (McCombs and Shaw Citation1972; Trenaman and McQuail Citation1961; Wanta and Ghanem Citation2007), algorithmically driven channels could have the capacity to shape users’ public issue salience having important implications for democracy (Dodds et al. Citation2023; Seipp et al. Citation2023).

Currently, news websites and social media are common channels for news consumption (Vermeer et al. Citation2020). However, news websites such as NOS and BBC, are part of media organizations, specifically public service media. These organizations have the duty to provide relevant news to the public with a diversity of subjects and perspectives, while promoting a shared public sphere (Nielsen et al. Citation2016). News websites, as part of public service news organizations, are also driven by this mission. Since the goal of news websites is to reflect society and create a shared public sphere, on an aggregated level individuals can get to see similar content when consuming information through news websites.

Differently from news websites, social media prioritizes individuals’ own news feed. Social media’s news feed is largely determined by algorithms, mixing several sources of information for the user (e.g., personal news, information from news organizations, advertisements, and other topics). The way that algorithms rank, organize and present information is largely unknown to the public (Thorson et al. Citation2021). Since the news feed is a combination of individuals’ preferences, their network, and other considerations that algorithms can optimize for (e.g., economic interests), each individual can be exposed to different information (Thorson et al. Citation2021). Exposure to different information can influence the diversity of the prioritized issue sets at the aggregated level, decreasing issue salience agreement across individuals.

Now, with the innovations in audio interfaces, the usage of CAs for news consumption is expected to rise in the upcoming years (NPO Citation2021; Weidmüller et al. Citation2021), becoming potential important gatekeepers of information (Weidmüller et al. Citation2021). Moreover, since CAs can act as media intermediaries it is important to understand their potential democratic implications in the media environment (Seipp et al. Citation2023). We refer to conversational agents as “software that accepts natural language as input and generates natural language as output, engaging in a conversation with the user” (Griol, Carbó, and Molina Citation2013, 760). This study focuses on a type of conversational agent: voice assistants. The usage of these types of CAs (i.e., voice assistants) varies but when asking for news individuals can: (1) decide the news sources of their preference or (2) let the algorithm decide the news outlets and, in many cases, the snippets of information they will hear (Doward, Salinas, and Sharpley Citation2019). However, in most interactions, users decide not to customize their information sources, letting algorithms select the content (Newman Citation2018). Algorithmic recommendations are based on prior knowledge from the users such as their location and language (Gannes Citation2019). Algorithmic decisions are also prioritized according to economic considerations (Ojeda Citation2021). Thus, individuals get exposed to news content from particular sources at the content visibility cost of other news publishers (Newman Citation2018). This way CAs can influence users’ shared knowledge by deciding the news sources and sets of information that individuals consume. The multiple news sources the algorithm optimizes for in CAs can lead to more diverse issue sets for the public than news websites. However, since social media is optimized with multiple inputs for news distribution (e.g., individuals’ preferences, networks, and other economic interests), we expect more diversity in individuals actively interacting with social media to access information. Thus, examining closely the differences in public issue salience between channels is key to understanding the dynamics of information and their influence on common knowledge.

To summarize, the selection processes on news websites as part of news organizations are driven by a shared set of journalistic values of a small number of editors. In contrast, the selection decisions behind CAs, as a direct medium for accessing news, are potentially driven by the different information needs and interests of a heterogeneous audience, which gives reason to assume that taken together those selections are more diverse. However, since social media mostly operates through inferred data from their users, at an aggregated level the selection and prioritization of information is more diverse (e.g., personal news, national news, global news, etc.) decreasing issue salience agreement across the users. Thus, we hypothesize:

H1: The issue sets prioritized by CA users will be more diverse than the issue sets prioritized by news website users, but less diverse than the issue sets by social media users.

The Conditioning Role of Media Trust

A key component for the transference of issue salience is media trust since it increases exposure and acceptance of information (Kalogeropoulos and Newman Citation2017). In general terms, trust refers to “a psychological state comprising the intention to accept vulnerability based upon positive expectations of the intentions or behavior of another” (van Duyn and Collier Citation2019, 33). Media trust is a multidimensional concept related to institutional trust, which refers to “the expected utility of institutions performing satisfactorily” (Mishler and Rose Citation2001, 31). In the media context, it explains individuals’ willingness to accept information that due to their limited resources are not able to verify (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020).

Trust has been considered a crucial variable for behavioral consequences and media effects such as political knowledge and participation (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020; Tsfati and Cappella Citation2005). In today’s complex media ecology, with a combination of news organizations and other media players (e.g., technological organizations), it has become more challenging to identify the relationship between media trust and its behavioral effects. Thus, investigating trust as a general concept would not be sufficient to capture the way that it works when individuals consume news through social media (e.g., Facebook) or news aggregators (e.g., Google Assistant). To capture some singularities in its relationship with media use, we propose to conceptualize media trust at two levels (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020).

The first level is generalized media trust, which refers to trust in news institutions or the press (Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). At this general level, trust is an important predictor of media use (Kalogeropoulos, Suiter, and Eisenegger Citation2019). Recent studies argue that high generalized media trust is associated with a wider media use of mainstream outlets, while lower levels are related to the usage of non-mainstream news sources, such as social media or news aggregators (Kalogeropoulos, Suiter, and Eisenegger Citation2019; Strömbäck et al. Citation2020). In addition, generalized media trust is related to confidence in public institutions, public engagement, and social trust (Hanitzsch, van Dalen, and Steindl Citation2018; Livio and Cohen Citation2018; Mishler and Rose Citation2001). Individuals with higher generalized media trust have a higher engagement with their communities, thus, learning about societal matters and having shared knowledge is key for their participation (Kim and Nelson Citation2021). News organizations and public service media (e.g., NOS) serve these audiences by informing them about societal relevant issues and fostering social cohesion (Nielsen et al. Citation2016). Thus, we argue that individuals with higher generalized media trust have higher news consumption through news websites tied to mainstream news organizations or public service media, as it is a direct source of information in comparison to social media or news aggregators. Consequently, more transference of the prominent issues discussed on the news websites will be transferred to the user. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H2a: Generalized media trust will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from general news websites.

H2b: Trust in the channel will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from news websites, CAs, and social media.

The Moderating Role of Attention

The relationships above are general expectations regarding trust, however, there are reasons to believe other factors play a role. Particularly, prior studies pointed out the influence of attention on issue salience (Chaffee and Schleuder Citation1986). News attention refers to a process of “increase in mental effort” for news consumption (Chaffee and Schleuder Citation1986, 3). Previous research argues that a difference exists between exposure and attention (Chaffee and Schleuder Citation1986; Strömbäck and Kiousis Citation2010). Although exposure to news is necessary to generate attention, individuals can be exposed to content without processing the information. Attention refers to an increase in mental effort, increasing the media’s impact (Jeong and Hwang Citation2012). Moreover, attention also influences recall of the information, thus individuals can learn and express the information that is relevant to them (Eveland Citation2003). Since attention to news drives learning and media impact, it is an important predictor of issue salience, while it is also connected to political knowledge and political socialization (Camaj Citation2014; Kiousis, McDevitt, and Wu Citation2005). In other words, attention encourages people to increase their knowledge about important topics and discuss it with others to prioritized them (Kiousis, McDevitt, and Wu Citation2005). Thus, drawing on the literature on issue salience, we expect that individuals with higher attention to the news in the channel used for news consumption will have higher transference of issue salience from the topics discussed in the channel. This leads to the following hypothesis:

H3: Attention to news will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from new websites, CAs, and social media to the individual.

Methodology

Design and Procedure

Recruitment

To answer the research question, a seven-day online panel survey among Google Assistant, Facebook, and NOS users in the Netherlands was conducted in October 2021. The selection of the Netherlands as a case study was mainly driven by two factors. Firstly, the country stands out for its advanced technological infrastructure and widespread adoption of new technologies (van Deursen et al. Citation2021). Secondly, the Netherlands benefits from a multiparty system and a Dutch public broadcaster that fosters discussions on less polarized issues, promoting social cohesion and aligning with community values (van der Goot et al. Citation2022; van Es and Poell Citation2020). This study expands upon previous research by considering the role of conversational agents, going beyond the focus on public service media and selected news intermediaries (e.g., social media). We pre-registered this study on the Open Science Framework.

Participants were recruited by an ISO-certified public opinion research company (Panel Inzicht) and first responded to an initial survey regarding channel usage and news consumption on Google Assistant, Facebook, and NOS. The survey helped to select the participants into one of the groups (Google Assistant, Facebook, NOS) based on the channel mostly used for news consumption. The final sample was composed of primary 352 news consumers, from which 112 were Google Assistant users, 126 were Facebook users, and 114 were NOS users. All participants provided informed consent. The age was between 18 and 90 (M = 56.5, SD = 16.7), 55% were male, and the average level of education was secondary vocational education (MBO).

Daily Questionnaire

The daily survey contained two questions: (1) What are the most important issues facing the country today? And (2) What are the most important issues in the news today? We refer to these two questions as issues in the country and issues in the news. These questions were asked in an open format and required participants to list five issues in a ranked manner. Around 4% of the reported issues were left blank or indicated as none. In addition, the first daily survey included the moderators (generalized media trust, trust in the channel and attention to the news) and the control variables (perceived lack of diversity, political orientation, political interest, and customization).

Content Analysis

Derived by the questions issues in the country and issues in the news we conducted a quantitative content analysis of 3965 issues to determine the dependent variable: issue salience agreement. The statements reported by the users were considered as the unit of analysis. The coding variables were events and issue topics. Events refer to the daily affairs happening in the world covered by the media (Lawrence Citation2000), while issue topics refer to the social problems that received coverage from news organizations (Dearing and Rogers Citation1996). To provide an example of both coding variables, a commonly mentioned issue was “Ajax”. At the issue topic level, the issue was coded as “Sports”. At event level, the issue was coded as “Ajax football game”. The coding instructions and codebook can be found in the OSF: tiny.cc/6xs3vz.

The codebook follows the instructions from the Manifesto Project and Comparative Agendas Project (Baumgartner, Breunig, and Grossman Citation2019; Wüst and Volkens Citation2003) for categorizing issue topics and events. To determine the events and issue topics, two bachelor students of Communication Science familiar with the Dutch media landscape were trained in December 2021 and January 2022. The categories used for the analysis of issue topics ranged between Krippendorff’s α ≥ .98 and α ≥ .66. The most common categories used to determine issue salience agreement scored above α ≥ .71 (e.g., General health issue α = .83, General housing issue α = .85, General education issues α = .71). However, to determine the reliability of the events we evaluated the agreement made between the two coders. The results showed a Krippendorff’s α ≥ .67 for the events.

Measures

Dependent Variable

Our main dependent variable is issue salience agreement a dichotomous variable (1 and 0) computed with 4 levels of analysis: (a) issues topics or (b) events arising across all participants (I) or within the channel (II). The variable is informed by the two questions: what are the most important (1) issues in the country and the (2) issues in the news. To determine issue salience agreement, after each day, we created a list of the top five issues mentioned across all channels (among all participants) and a list of the top five issues mentioned by participants of each channel (within channels). Then, to create the dichotomous variable we scored the issues whenever participants mentioned the topics from the lists (among all the participants, and within the channel).

Independent Variable

The main independent variable was the group to which the participant was assigned during the recruitment (Google Assistant, NOS, or Facebook, for details: OSF tiny.cc/6xs3vz). The exact questions to determine channel usage was “How often in the past week do you use Google Assistant/Facebook/NOS.nl” and for news consumption was “How often in the past week do you consume through Google Assistant/Facebook/NOS.nl”. In both questions, respondents indicated the frequency of news exposure on each of the channels. The response categories ranged from 1 (never), 2 (1–2 days a week), 3 (3–4 days a week), 4 (5–6 days a week), 5 (daily).

Moderators

Generalized Media Trust

The first moderator was generalized media trust, measured using an adjusted version of Newman et al. (Citation2016) scale. The scale asked to indicate the level of agreement to 7 different statements through a 7 Likert scale from strongly disagree − 1 to strongly agree − 7. Some of the statements included were “I think I can trust the news most of the time” and “I think I can trust journalists most of the time”. After following a confirmatory factor analysis, we created a scale for generalized media trust based on the average of all the items (M = 4.6, SD = 0.61, Cronbach’s α = .86). The complete scales used can be found here: tiny.cc/6xs3vz.

Media Trust in the Channel

The variable was measured using five statements (Newman et al. Citation2016). An example of the exact wording included “I think you can trust news on Facebook most of the time”. The complete scales used can be found here. The items were averaged to create scale ranging from 0 to 7 for each channel (M = 4.04, SD = 0.76, Cronbach’s α = .72).

Attention to the News

The variable was measured depending on the channel the participants were invited to. For example, Google Assistant participants only responded about attention on Google Assistant. We used a single item from Chaffee and Schleuder (Citation1986) scale, the exact wording was “When I use Google Assistant in my Google home/Facebook/NOS I do it with” (Far too little attention − 1 to Far too much attention − 7) (M = 4.03, SD = 1.07). The complete scales used can be found in tiny.cc/6xs3vz. In , we present the means and standard deviations of each moderator for every channel.

Table 1. Means and stand deviations of moderators per channel.

Control Variables

We controlled for perceived lack of diversity, political interest, political orientation, and customization. First, perceived lack of diversity (M = 4.42, SD = 0.95, Cronbach’s α = 0.74) was selected as a control because empirical research suggests that the perceptions of diversity can vary across channels and users (Bodó et al. Citation2019; van der Wurff Citation2011). Second, political interest (M = 3.23, SD = 1.04) was selected as it is also a strong predictor of exposure to political information and a known moderator of media effects resulting from such exposure. Third, we control for political orientation (M = 5.72, SD = 2.14) as it is also related to issue perceptions (Kiousis, McDevitt, and Wu Citation2005). Fourth, we control for customization (M = 2.69, SD = 1.61) as all of the channels offer features to prioritize content or limit the exposure of certain topics (Wells and Thorson Citation2017). Finally, we controlled for demographics such as age, gender, and education. The following link: tiny.cc/6xs3vz provides a complete overview of the scales.

Results

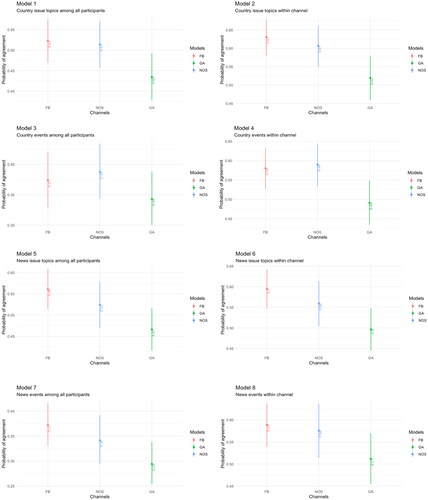

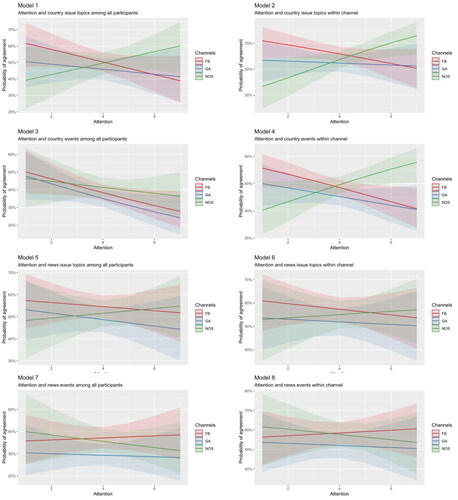

We present the overall results in . The models are based on a dichotomous variable (1/0), where 1 indicates the reported issue is in the list of top five issue topics or events. Since we had four dependent variables (agreement level: within channel vs. among all participants; issue level: events vs. issue topics) tested among two issue types (i.e., in the country vs. in the news), we created eight models using a multilevel analysis to test the hypotheses. The multilevel models were used since the unit of analysis, (issue salience agreement) could be clustered into days and participants. The models are outlined in .

Table 2. Model outline overview.

Table 3. Model comparisons.

Results are graphically shown in presenting the estimated probability of issue salience agreement across the eight models described in .

Figure 2. Estimated probabilities of issue salience agreement across models.Footnote1

Issue Salience Agreement across Channels

Our first hypothesis, the issue sets prioritized by CA users will be more diverse than the issue sets prioritized by news website users, but less diverse than the issue sets by social media users is not supported (). Social media and news websites do not show statistical differences. However, the models suggest participants consuming information through CAs have lower probabilities of issue salience agreement for country issue topics, news issue topics and news events (Model 1, Model 2, Model 5, Model 6, Model 7, Model 8). Additionally, some patterns in the models emerged during the analysis. shows participants consuming news from CAs (Google Assistant) tend to have lower levels of agreement on the events and issue topics mentioned among all participants for the issues in the country and issues in the news compared to news websites and social media. In addition, news websites users have a higher probability of issue salience agreement in Model 3 and Model 4, while social media news consumers have a higher probability of issue salience agreement for news issue topics and events among all participants (Model 1, Model 2, Model 5, Model 6, Model 7 and Model 8). Importantly, in most scenarios, the difference between social media and news websites falls within the confidence interval levels and the differences tend to be small.

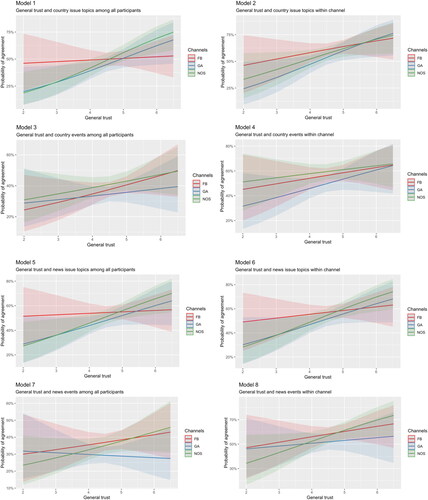

The Conditioning Role of Media Trust

In addition, we tested whether generalized media trust and trust in the specific channel influence the transference of salience. The lack of statistical significance between generalized media trust and the channels (see ) does not provide support to H2a, which predicted generalized media trust will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from news websites (NOS).

However, when looking at the general patterns, demonstrates higher levels of general trust increase issue salience agreement. We also see a higher probability of issue salience agreement for news websites participants with high levels of trust, compared to social media and CAs. In addition, Model 4 describes country events within channel and Model 7 shows news events among all participants have lower issue salience agreement for CA users.

Figure 3. Estimated probabilities of generalized media trust across models.Footnote2

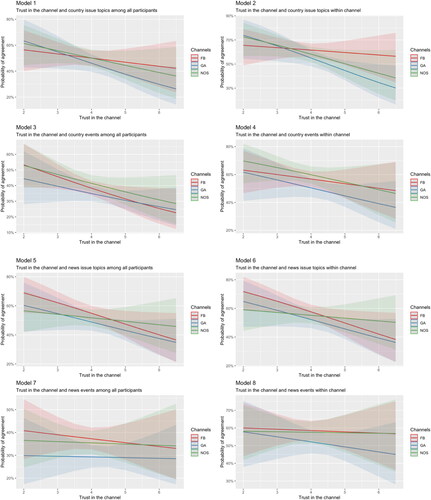

H2b theorized trust in the channel will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from news websites (NOS), CAs (Google Assistant), and social media (Facebook). The interaction effects in the models are not statically significant (). Thus, hypothesis H2b is not supported.

However, trust in the channel is a significant predictor of issue salience agreement for country events among all participants and news issue topics (Model 3, Model 5 and Model 6). We also observe less issue salience agreement for issues in the country in all channels for participants with high levels of trust in the channel (Model 1, Model 2, Model 3, and Model 4), while for issues in the news (Model 5, Model 6, Model 7, and Model 8) we observe different patterns. First, individuals trusting social media have a lower probability of issue salience agreement in most models (Model 5, Model 6, Model 7), an exception is Model 8, where users maintain similar levels of issue salience agreement. Second, individuals trusting CAs have lower probabilities of issue salience agreement in most models (Model 5, Model 6, Model 8), Model 7 regarding news events among all participants are an exception where users also have similar levels of issue salience agreement. Third, have individuals trusting news websites have similar probabilities issue salience agreement across all models analyzing issues in the news (Model 5, Model 6, Model 7, and Model 8) ().

Figure 4. Estimated probabilities of trust in the channel across models.Footnote3

The Interaction between Attention to the News and Channel

It is interesting to note similar patterns in attention to the news as moderator. Attention is a significant predictor of issue salience agreement for country events among all participants and within channel (Model 3 and Model 4). Additionally, the interaction effects between attention to the news and NOS are significant () for the issue topics in the country within channel (Model 2). However, since H3 predicted attention to the news will positively moderate the transference of issue salience from new websites (NOS), CAs (Google Assistant), and social media (Facebook) and most of the models lack statistical significance H3 is not supported ().

We thus proceed to analyze each of the models. First, participants paying attention to the information on news websites have higher probabilities of issue salience agreements for issues topics in the country among all participants and within the channel, (Model 1 and Model 2). Additionally, in Model 4 describing country events within channels we see participants with a higher attention to news in news websites have higher probability of issue salience agreement.

In contrast, participants paying attention to the news on social media have fewer probabilities of issue salience agreement at various levels of analysis (events and issue topics) (Model 1, Model 2, Model 3, Model 4, Model 5, and Model 6). As an exception, Model 7 and Model 8 suggest no changes in issue salience agreement for social media news consumers. Similarly, for CA users, we see participants with higher attention to news in CAs have lower probabilities of issue salience agreement for country issue topics among all participants (Model 1), country events among all participants (Model 3), country events within channel (Model 4) and news issue topics among all participants and within channel (Model 5 and Model 6 However, Model 7, and Model 8 describing news events indicate no changes of issue salience agreement for CA users ().

Figure 5. Estimated probabilities of attention to the news across models.Footnote4

Control Variables

shows that several control variables are significant predictors of issue salience agreement. Age is a positive predictor of issue salience agreement for country issue topics and events among all participants, as well as within channel, for news issue topics among all participants and within channel, and for news events within channel (as shown in Model 1, Model 2, Model 3, Model 4, Model 5, Model 6, and Model 8). Education is also a significant predictor of issue salience agreement for country events among all participants and within channel (as shown in Model 3 and Model 4). Gender is significant for country issue topics and events within channel (as shown in Model 2 and Model 4). Perceived lack of diversity is also an important factor increasing issue salience agreement for news issue topics among all participants and within the channel (as shown in Model 5 and Model 6). Customization, political orientation, and political interests were not found to be significant variables for issue salience agreement.

Discussion

We ran a seven-day longitudinal survey in the Netherlands, comparing three channels for news consumption: CAs (Google Assistant), social media (Facebook), and news websites (NOS) to understand how conversational agents influence public issue salience in a complex media landscape. While our hypotheses are not supported, our study provides empirical evidence on how different channels may influence issue salience agreement.

Firstly, a key finding is that, compared to social media and news websites, CAs news consumers seem have less agreement about the important issues for the country. The pattern was consistent when considering the overall issues for the country provided by the whole sample, and when only considering their channel. Consequently, and aligned with a prior report (Weidmüller et al. Citation2021), our results imply that individuals mainly informing themselves through CAs might have a more diverse view on the relevant issues in the country than individuals using news websites for news consumption. Thus, CAs’ users get exposed to particular sources at the cost of other news publishers (Newman Citation2018). A possible explanation could be that news in CAs differs according to participants’ characteristics and input (e.g., location and language), which may lead to the information provided being targeted to individual preferences (Gannes Citation2019; Ojeda Citation2021). If validated in future research, these trends could suggest CAs could lead to less issue salience agreement, having important democratic implications for shared public sphere (Seipp et al. Citation2023).

Secondly, the results of our study suggest news website users in comparison to CAs have a higher probability of agreeing on the important events that are relevant for the country among all participants and within the channel. Since news organizations are mainly driven by journalistic values, publishers select news stories with diverse subjects and perspectives while promoting a shared public sphere (Deuze Citation2005; Nielsen et al. Citation2016). In this sense, we see users consuming similar news events, following a common agenda at country level.

Thirdly, surprisingly, and contrary to our expectations, our results indicate social media users in comparison to those consuming news via CAs have a significantly higher probability of agreeing on the important issues and events. This novel finding suggests that although social media can create unique news feeds for every user (Thorson et al. Citation2021), social media news consumers can have a shared understanding of the relevant topics in the country. Possibly, social media’s algorithm can be also optimized for distributing popular news (e.g., public health threats, safety, and political debates), together with personalized content (Meta Citation2022). However, we emphasize the overlap in the confidence intervals when comparing the channels. Thus, we recommend future work to examine the degree of news personalization in social media and compare it with issue salience agreement among users in different channels.

Regarding our moderators, we see the interactions between generalized trust and the channels were not significant. Nevertheless, our findings suggest that compared to social media and CAs, individuals with more generalized media trust consuming information through news websites have higher issue salience agreement for issues topics. Thus, traditional news sources play an important role in creating social cohesion at issue topics level compared to algorithmic channels. Since general trust is related to news consumption through traditional media and public knowledge (Kalogeropoulos, Suiter, and Eisenegger Citation2019), news websites can help to create a shared public sphere for relevant issues in the country.

Moreover, we see that trust in the channel was a predicting variable of issue salience agreement for news issue topics. Since confidence in a channel influence the acceptance of the information distributed in the channel (Martens et al. Citation2018), in the context of algorithmically driven platforms it is highly relevant to hold CAs and social media accountable to prevent unintended consequences for democracy (Weidmüller et al. Citation2021). Although, the interaction between trust in the channel and the channels (e.g., CAs, social media and news websites) was not significant, the models pointed out lower probabilities of issue salience agreement with higher trust in the channel, especially for algorithmically driven channels (i.e., CAs and social media). In the context of CAs, asking for news is an efficient way for news consumption (Martens et al. Citation2018), however, the mode of the interaction could also have implications on the acceptance of the information (Foehr and Germelmann Citation2020). Thus, further research should address in-depth the impact of media trust in algorithmically driven channels (e.g., CAs and social media) examining the interaction from the users with the channels and the content that is distributed in these platforms.

Attention to the news can also act as a mechanism for issue salience agreement, especially when information is consumed through news websites. Individuals consuming information through news websites learn about the distinct issues and daily events occurring in the country. Since attention to news relates to an increased mental effort for information processing (Chaffee and Schleuder Citation1986) and information recall (Eveland Citation2003), our results point out attention to news in news websites allows users to learn and discuss diverse events while reaching mutual understanding of the relevant issues. The contrary pattern emerges for individuals paying attention to news in CAs or social media as users have lower issue salience agreement for issues and events in the country. However, since the interactions were not significant, we recommend future research to evaluate the impact of attention to the news focusing on algorithmically driven channels and to compare (1) the content conveyed by each channel with individual’s perceptions and (2) the level of attention in each of the channels.

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, since the adoption of CAs at home is still an emerging phenomenon, recruiting participants with Google Assistant as their main source for news consumption was challenging. It is important to consider CAs users might also consume news through other sources.

Second, our results point out that some of the users’ characteristics play an important role in issue salience agreement such as age, gender, education, and perceived lack of diversity. Conversely, political orientation, political interests and customization of the source did not predict issue salience agreement. We, therefore, recommend future research to consider other methods for studying CAs’ news consumers such as providing the CA to different types of users and asking them to interact with it.

Third, in the context of CAs, worldwide companies (e.g., Google, Amazon, Apple) have access to information flows that could lead to distinctions in issue salience. In this study, we focus on a specific conversational agent (Google Assistant), however, each CA follows its own logic to interact with the public. Additionally, it is necessary to highlight that Google Assistant is one of the access points for information and news consumption offered by the same organization. The interoperability of companies like Google represents an opinion power that should be undermined. Thus, we recommend future studies to compare the differences between distinct types of CAs as well as different channels from the same institution.

Fourth, it should be acknowledged that selecting the Netherlands as a case study brings limitations on the generalizability of the findings. Despite the Netherlands being advanced in technology adoption, the use of conversational agents for news consumption is still in its early stages. However, we believe that in countries where news consumption through conversational agents is more prevalent and discussions on polarizing topics are more prominent, the effect of issue salience agreement in conversational agents might be heightened. Therefore, future research should replicate this study in other countries to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of conversational agents on issue salience agreement.

This study provides empirical evidence about the impact of news consumption through CAs on issue salience agreement, highlighting the potential democratic implications of different channels. For instance, CAs news consumers could have a different understanding of the relevant issues in the country, affecting shared knowledge among citizens (Bodó et al. Citation2019).

Different to prior research, our study also provides a new way of analyzing issue salience agreement within different online channels by addressing issue salience at different levels of analysis (issue topics and events). Altogether, we show patterns of the impact that different online channels have on issue salience. The emerging adoption of CAs shows the complexity of the current media environment, which can further exacerbate differences between public issue salience. CAs adoption at home for news consumption is increasing, and despite their relevance, we have limited knowledge of their effects. Our research poses new questions on the democratic implications that CAs bring to the media and democracy, such as the extent to which these technologies will affect shared knowledge when adoption is higher.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The figure shows the estimated means ranging from 30% to 60% on issue salience agreement for each of the channels. The channels are abbreviated as followed: Facebook (FB), NOS (NOS), Google Assistant (GA).

2 The figure shows the estimated means ranging from 20% to 75% on issue salience agreement in interaction with general trust, for each of the channels. The channels are abbreviated as followed: Facebook (FB), NOS (NOS), Google Assistant (GA).

3 The figure shows the estimated means ranging from 20% to 70% on issue salience agreement in interaction with trust in the channel, for each of the channels. The channels are abbreviated as followed: Facebook (FB), NOS (NOS), Google Assistant (GA).

4 The figure shows the estimated means ranging from 20% to 70% on issue salience agreement in interaction with attention, for each of the channels. The channels are abbreviated as followed: Facebook (FB), NOS (NOS), Google Assistant (GA).

References

- Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., and Grossman, E., eds. 2019. Comparative Policy Agendas: Theory, Tools, Data. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198835332.001.0001

- Bodó, B., N. Helberger, S. Eskens, and J. Möller. 2019. “Interested in Diversity: The Role of User Attitudes, Algorithmic Feedback Loops, and Policy in News Personalization.” Digital Journalism 7 (2): 206–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1521292

- Camaj, L. 2014. “Need for Orientation, Selective Exposure, and Attribute Agenda-Setting Effects.” Mass Communication and Society 17 (5): 689–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2013.835424

- Chaffee, S., and J. Schleuder. 1986. “Measurement and Effects of Attention to Media News.” Human Communication Research 13 (1): 76–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1986.tb00096.x

- Dambanemuya, H. K., and N. Diakopoulos. 2020. “Alexa, What is Going on with the Impeachment? Evaluating Smart Speakers for News Quality.” Proc. Computation + Journalism Symposium, 5.

- Dearing, J. W., and E. M. Rogers. 1996. Agenda-Setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452243283

- Dennison, J. 2019. “A Review of Public Issue Salience: Concepts, Determinants and Effects on Voting.” Political Studies Review 17 (4): 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929918819264

- Deuze, M. 2005. “What is Journalism?” “Professional Identity and Ideology of Journalists Reconsidered.” Journalism 6 (4): 442–464. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884905056815

- Diakopoulos, N. 2019. Automating the News: How Algorithms Are Rewriting the Media. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Dodds, T., C. de Vreese, N. Helberger, V. Resendez, and T. Seipp. 2023. “Popularity-Driven Metrics: Audience Analytics and Shifting Opinion Power to Digital Platforms.” Journalism Studies 24 (3): 403–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2167104

- Doward, L., B. Salinas, and A. Sharpley. 2019. “News on assistant and experiments in voice journalism.” International journalism festival. https://www.journalismfestival.com/programme/2019/news-on-assistant-experiments-in-voice-journalism

- Eveland, W. P. 2003. “A “Mix of Attributes” Approach to the Study of Media Effects and New Communication Technologies.” Journal of Communication 53 (3): 395–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02598.x

- Foehr, J., and C. C. Germelmann. 2020. “Alexa, Can I Trust You? Exploring Consumer Paths to Trust in Smart Voice-Interaction Technologies.” Journal of the Association for Consumer Research 5 (2): 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1086/707731

- Gannes, L. 2019. “Hey Google, play me the news.” Google. https://blog.google/products/news/your-news-update/

- Griol, D., J. Carbó, and J. M. Molina. 2013. “An Automatic Dialog Simulation Technique to Develop and Evaluate Interactive Conversational Agents.” Applied Artificial Intelligence 27 (9): 759–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/08839514.2013.835230

- Hanitzsch, T., A. van Dalen, and N. Steindl. 2018. “Caught in the Nexus: A Comparative and Longitudinal Analysis of Public Trust in the Press.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 23 (1): 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740695

- Helberger, N. 2020. “The Political Power of Platforms: How Current Attempts to Regulate Misinformation Amplify Opinion Power.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888

- Jeong, S. H., and Y. Hwang. 2012. “Does Multitasking Increase or Decrease Persuasion? Effects of Multitasking on Comprehension and Counterarguing.” Journal of Communication 62 (4): 571–587. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01659.x

- Jones, B., and R. Jones. 2019. “Public Service Chatbots: Automating Conversation with BBC News.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 1032–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1609371

- Kalogeropoulos, A., and N. Newman. 2017. ‘I saw the news on Facebook’ : brand attribution when accessing news from distributed environments. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3005412

- Kalogeropoulos, A., J. Suiter, and M. Eisenegger. 2019. “News Media Trust and News Consumption: Factors Related to Trust in News in 35 Countries.” International Journal of Communication 13: 22.

- Kim, S. J., and J. L. Nelson. 2021. “Improve Trust, Increase Loyalty? Analyzing the Relationship between News Credibility and Consumption.” Journalism Practice 15 (3): 348–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1719874

- Kiousis, S., M. McDevitt, and X. Wu. 2005. “The Genesis of Civic Awareness: Agenda Setting in Political Socialization.” Journal of Communication 55 (4): 756–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb03021.x

- Krosnick, J. A. 1990. “Government Policy and Citizen Passion: A Study of Issue Publics in Contemporary America.” Political Behavior 12 (1): 59–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00992332

- Lawrence, R. G. 2000. “Game-Framing the Issues: Tracking the Strategy Frame in Public Policy News.” Political Communication 17 (2): 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/105846000198422

- Livio, O., and J. Cohen. 2018. “Fool Me Once, Shame on You”: Direct Personal Experience and Media Trust.” Journalism 19 (5): 684–698. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884916671331

- Martens, Bertin, Luis Aguiar, Estrella Gomez, and Frank Mueller-Langer. 2018. “The Digital Transformation of News Media and the Rise of Disinformation and Fake News.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3164170

- McCombs, M. E., and D. L. Shaw. 1972. “The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media.” Public Opinion Quarterly 36 (2): 176–187. https://www.jstor.org.proxy.uba.uva.nl:2048/stable/2747787. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

- Meta. 2022. “Approach to newsworthy content.” https://transparency.fb.com/features/approach-to-newsworthy-content/

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34 (1): 30–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414001034001002

- Newman, N. 2018. “The future of voice and the implications for news.” https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/our-research/future-voice-and-implications-news

- Newman, N. 2022. Journalism, media, and technology trends and predictions 2022.

- Newman, N., R. Fletcher, D. Levy, and R. K. Nielsen. 2016. Reuters institute digital news report 2016.

- Nielsen, R. K., R. Fletcher, A. Sehl, and D. Levy. 2016. Analysis of the relation between and impact of public service media and private media.

- NPO. 2021. Technologische ontwikkelingen in het mediadomein.

- Ojeda, C. 2021. “The Political Responses of Virtual Assistants.” Social Science Computer Review 39 (5): 884–902. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439319886844

- Paul, H. L., and J. Fitzgerald. 2021. “The Dynamics of Issue Salience: Immigration and Public Opinion.” Polity 53 (3): 370–393. https://doi.org/10.1086/714144/SUPPL_FILE/21018APPENDIX.PDF

- Seipp, T. J., N. Helberger, C. De Vreese, and J. Ausloos. 2023. “Dealing with Opinion Power in the Platform World: Why We Really Have to Rethink Media Concentration Law.” Digital Journalism 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2161924

- Shehata, A., and J. Strömbäck. 2013. “Not (yet) a New Era of Minimal Effects: A Study of Agenda Setting at the Aggregate and Individual Levels.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 18 (2): 234–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161212473831

- Strömbäck, J., and S. Kiousis. 2010. “A New Look at Agenda-Setting Effects—Comparing the Predictive Power of Overall Political News Consumption and Specific News Media Consumption across Different Media Channels and Media Types.” Journal of Communication 60 (2): 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2010.01482.x

- Strömbäck, J., Y. Tsfati, H. Boomgaarden, A. Damstra, E. Lindgren, R. Vliegenthart, and T. Lindholm. 2020. “News Media Trust and Its Impact on Media Use: Toward a Framework for Future Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 44 (2): 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2020.1755338

- Su, L., and X. Li. 2021. “Perceived Agenda-Setting Effect in International Context: Impact of Media Coverage on American Audience’s Perception of China.” International Communication Gazette 83 (7): 708–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748048520984029

- Thorson, K., K. Cotter, M. Medeiros, and C. Pak. 2021. “Algorithmic Inference, Political Interest, and Exposure to News and Politics on Facebook.” Information, Communication & Society 24 (2): 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1642934,

- Trenaman, J., and D. McQuail. 1961. Television and the political image: A study of the impact of television on the 1959 general election.

- Tsfati, Y., and J. N. Cappella. 2005. “Why Do People Watch News They Do Not Trust? The Need for Cognition as a Moderator in the Association between News Media Skepticism and Exposure.” Media Psychology 7 (3): 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0703_2

- van der Goot, E., S. Kruikemeier, J. de Ridder, and R. Vliegenthart. 2022. “Online and Offline Battles: Usage of Different Political Conflict Frames.” The International Journal of Press/Politics. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/19401612221096633

- van der Wurff, R. 2011. “Do Audiences Receive Diverse Ideas from News Media? Exposure to a Variety of News Media and Personal Characteristics as Determinants of Diversity as Received.” European Journal of Communication 26 (4): 328–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323111423377

- van Deursen, A. J. A. M., A. van der Zeeuw, P. de Boer, G. Jansen, and T. van Rompay. 2021. “Digital Inequalities in the Internet of Things: Differences in Attitudes, Material Access, Skills, and Usage.” Information Communication and Society 24 (2): 258–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1646777

- van Duyn, E., and J. Collier. 2019. “Mass Communication and Society Priming and Fake News: The Effects of Elite Discourse on Evaluations of News Media.” Mass Communication and Society 22 (1): 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2018.1511807

- van Es, K., and T. Poell. 2020. “Platform Imaginaries and Dutch Public Service Media.” Social Media + Society 6 (2): 205630512093328. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933289

- Vermeer, S., D. Trilling, S. Kruikemeier, and C. de Vreese. 2020. “Online News User Journeys: The Role of Social Media, News Websites, and Topics.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1114–1141. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1767509

- Wanta, W., and S. Ghanem. 2007. “Effects of agenda setting.” In Mass Media Effects Research: Advances Through Meta-Analysis, 37–51.

- Weidmüller, L., K. Etzrodt, F. Löcherbach, and J. Möller. 2021. Ich höre was, was du nicht hörst auf einen blick: Warum eine studie?

- Wells, C., and K. Thorson. 2017. “Combining Big Data and Survey Techniques to Model Effects of Political Content Flows in Facebook.” Social Science Computer Review 35 (1): 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439315609528

- Wüst, A., and A. Volkens. 2003. Euromanifesto coding instructions.

- Zarouali, B., M. Makhortykh, M. Bastian, and T. Araujo. 2021. “Overcoming Polarization with Chatbot News? Investigating the Impact of News Content Containing Opposing Views on Agreement and Credibility.” European Journal of Communication 36 (1): 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267323120940908