Abstract

Despite it being somewhat of a niche project back in 2009, at this stage of its evolution, data journalism has gained significant traction to grow into a maturing field. However, little is known about the intersection of data journalism and collaboration in the news organizations’ business models from an infrastructure perspective, that is, key activities, key resources, and partner networks. These elements play an important role in the business model as they outline how an organization can optimize the efficiency within the business to provide the public with the best value proposition, in this case, data storytelling. Therefore, through a systematic literature review, this study aims to identify research trends and gaps in the field, conceptualize current paradigmatic views and therein provide clear propositions to guide future research in the entanglements of data journalism, collaboration, and business models. The originality of this study is rooted in the comprehensive search and systematic review of studies in the discourse around data and collaborative journalisms as part of the news organizations’ business models, which have not been unified to date, although both practices became popularized with the digitization of news organizations.

Introduction

In recent years, data journalism has attracted significant attention from scholars in different fields and produced an increasing number of publications in various areas (Mutsvairo Citation2019). Although data journalism was not widely popular in 2009, it has now become a well-established field with significant growth. This development can be attributed to the success of the Panama Papers investigation, a joint effort by over 370 journalists from 100 media outlets in 80 countries, which exposed the secretive operations of the unstructured data in the offshore economy (Lück and Schultz Citation2019). Journalists, designers, and technologists from different news outlets around the world worked collaboratively to bring this story to light in an engaging way. This project still serves as an important reminder of how collaborative journalism and data analytics can aid the news work process (Carson and Farhall Citation2018).

However, little is known about the intersection between data journalism and collaboration in news organizations’ business models from an infrastructure perspective, that is, key activities and key resources, and partner networks (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010). These elements play an important role in the business model because they outline how an organization can optimize efficiency within the business to provide the best value to the public: data-backed storytelling. Through a systematic literature review, this study aims to identify research trends and gaps in the field, and conceptualize current paradigmatic views, thereby providing clear propositions to guide future research regarding the entanglements between data journalism, collaboration, and business models.

Based on a systematic review of 55 peer-reviewed articles, taken from the Scopus® and Web of Science® databases, this study provides a descriptive analysis, with results that synthesize current research trends and account for gaps in the literature. To my knowledge, this study is original because of the comprehensiveness of the search conducted and the systematic review of studies creating the discourse around news organizations that use data and collaborative journalism as part of their business models, which to date have not been unified, though both practices have become popular with the digitization of news.

The aim of this systematic literature review, accordingly, is threefold. Using inclusion-exclusion criteria (Higgins et al. Citation2011; Mohamed Shaffril, Samsuddin, and Abu Samah Citation2021), the first goal is to identify the general trends observed in the rapidly growing research on data journalism and collaboration. Second, this review looks at data journalism scholarship through the lens of business infrastructure, as proposed in the Business Model Canvas (BMC) by Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010). The BMC describes the rationale for how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value under nine building blocks that are somehow interconnected. These building blocks cover four main areas: customers, infrastructure, financial viability, and offering (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010). Infrastructure is the focus here due to its importance to the business models of news media organizations: it describes the key activities (understood as journalistic norms and routines), key resources (what is necessary to create value to the public), and partner network (found in collaborative journalism in the strategic alliances that news outlets adopt to deploy cooperative projects as well as other relationships that optimize operations and reduce business risks). Lastly, this study provides clear information about current scholarship on data journalism, collaboration, and business models, which consequently reveals research gaps and helps generate propositions for future research.

Method

Through a systematic literature review, this paper aims to locate and synthesize related research through organized, transparent, and replicable processes that include predefined search strings as well as standard inclusion and exclusion criteria (Higgins et al. Citation2011; Mohamed Shaffril, Samsuddin, and Abu Samah Citation2021). This methodology is built on existing evidence, which allows researchers to identify gaps and directions for future research. In order to do so, qualitative techniques of pattern matching and explanation building have been employed to descriptively categorize published, peer-reviewed studies, highlighting commonalities and disparities using the eyeballing technique (Bhimani, Mention, and Barlatier Citation2019). Therefore, a descriptive, rather than a statistical, analysis of results is presented here.

Tranfield, Denyer, and Smart (Citation2003) laid out a three-stage procedure for producing a systematic literature review: planning, execution, and guided reporting. The first step is to set the research objectives that support a broad scan of articles. This study focuses on peer-reviewed journal articles, as they are considered to have the greatest impact on research integrity and retention (Podsakoff et al. Citation2005). To best capture the entanglements between data journalism, collaboration, and business models, this study uses predefined selection categorization driven by previous studies (Bhimani, Mention, and Barlatier Citation2019; Iden, Methlie, and Christensen Citation2017; Mohamed Shaffril, Samsuddin, and Abu Samah Citation2021).

In order to assess the range of paradigms, definitions, and operationalizations related to data journalism, as seen under the collaboration and business model lens, I adopted one of the four main areas of a business according to Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010) BMC. In it, business model patterns can be described in terms of the most important activities a company must perform (key activities), the most important assets required to perform these activities (key resources), and the partner network that makes the strategy work (key partnerships). This provides a framework for understanding how news media companies capture value by collaborating systematically with internal and external partners (Heft and Baack Citation2022; Westlund, Krumsvik, and Lewis Citation2021; Westlund and Ekström Citation2021). This reveals the conceptual and empirical evidence through a cross-disciplinary synthesis of data, which addresses the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the entanglements between data journalism, collaboration, and business models?

RQ2. How has current data journalism scholarship posed collaborative journalism in the news industry’s business models?

RQ3. From a collaborative perspective, what are the avenues of research for the future development of data journalism in the news industry?

This study relied on a combination of keywords to search for relevant primary studies. In order to include only journal articles that covered “data journalism,” from the perspectives of “collaboration” and “business model,” terms such as “data-driven journalism” and “collaborative,” as well as similar terms, were used. Thus, the final search strings included:

“data journalism” AND “collaboration”;

“data journalism” AND “collaborative”;

“data-driven journalism” AND “collaboration”;

“data-driven journalism” AND “collaborative”;

“data journalism” AND “business model”;

“data-driven journalism” AND “business model.”

English-language, peer-reviewed articles were searched for these terms within their titles, abstracts, keywords, and body text. The collected database consists of 354 materials from Scopus® and 31 from Web of Science®. Collected data covers the period up until July 2021 (no time restrictions for the earliest publication). This means that the review includes all relevant publications were available up until that date. Any developments or new research published after July 2021 may not be included in the review, but they can be considered in future updates or revisions of this review.

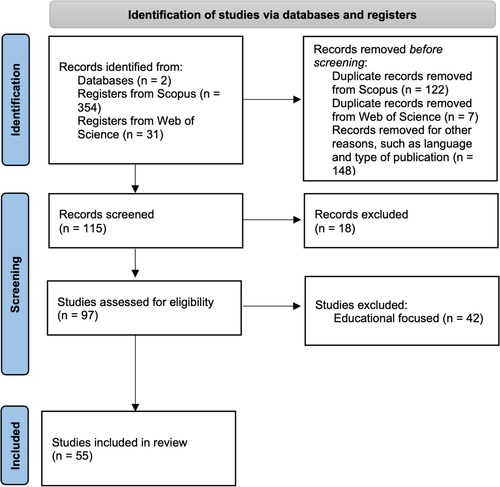

Articles without the terms “collaboration,” “collaborative,” or “business model” in the title, abstract, and keywords were excluded. Duplicate articles were also excluded. Another exclusion criterion was articles not written in English (n = 18). If an article was educational and not practical, it was also excluded from our final dataset, as this study seeks to understand the strategic value of data journalism from the practitioner’s viewpoint (n = 42). describes these steps in detail.

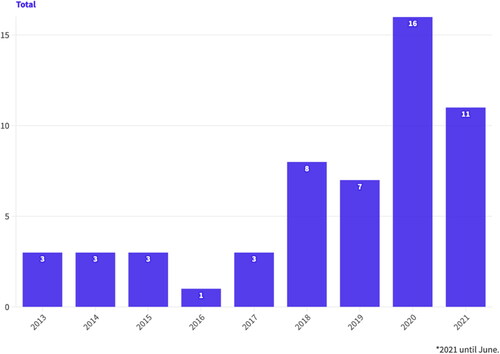

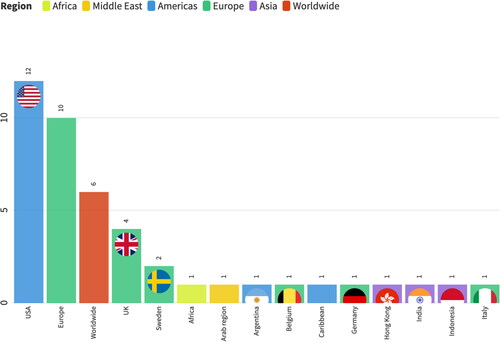

The inclusion criteria were articles that included the above-mentioned terms or discussed the collaboration and business model aspects of data journalism. The final dataset consisted of 55 peer-reviewed articles, which covered a range of countries and regions, with the majority being from the United States and Europe (about 41%; ). In the case of Europe, it was considered articles that cover more than one European country. Similarly, Worldwide data journalism research refers to studies that encompass more than one country in different continents. Additionally, our dataset shows that most of these articles were published in recent years. In 2018, there was a significant increase to eight publications, followed by a slight decrease to seven in 2019. The most recent years, 2020 and 2021 (until June), saw the highest values with 16 and 11, respectively. This information is presented in .

Figure 2. The countries and regions included in the studies about data journalism. Only studies covering a region or country were included in this chart (n = 44).

Most of these articles took a qualitative approach to developing an understanding of the different perspectives on data journalism. Interviews were the most common method, followed by survey (13.64%), content analysis (13.64%), and case study (12.12%). summarizes the main methodological designs these studies used.

Table 1. Methodological approaches and study designs of the examined empirical studies.

In order to achieve this paper’s aim of systematically identifying the breadth of literature about data journalism, which specifically pertains to collaboration and business models, the results are presented according to Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010) infrastructure categorization: key resources, key activities, and partner network.

For the analysis, thematic analysis was used (Braun and Clarke Citation2006, Citation2019). This is a commonly used method to analyze qualitative data in humanities and social sciences research. According to Braun and Clarke (Citation2012), thematic analysis is a useful tool for conducting a systematic and comprehensive review of the literature. The authors suggest that using thematic analysis allows researchers to identify key themes and patterns in the data. Furthermore, the thematic analysis used a deductive approach, which involves coming to the data with some preconceived themes. In this study, themes were conceived from Osterwalder and Pigneur (Citation2010) infrastructure categorization. Thus, it is expected to find reflected these themes in the data, based on this existing knowledge. It was also adopted the latent approach, that is, reading into the subtext and assumptions underlying the data. This means that implicit meanings were analyzed in addition to the explicit ones of the data. It is required because in this analysis is necessary to look beyond what is explicitly stated in the articles and identify any hidden or implicit meanings that may be present and may not provide a complete understanding of the themes being analyzed. Overall, the use of thematic analysis in this literature review provides a rigorous and structured approach to analyzing and synthesizing the existing research on data journalism, business models, and collaboration. Additionally, thematic analysis can help to identify gaps in the literature and highlight areas for further investigation.

The next section presents a descriptive analysis of the emerging trends and addresses each of the proposed research questions.

Findings and Discussion

Data Journalism as a News Company’s Business Model

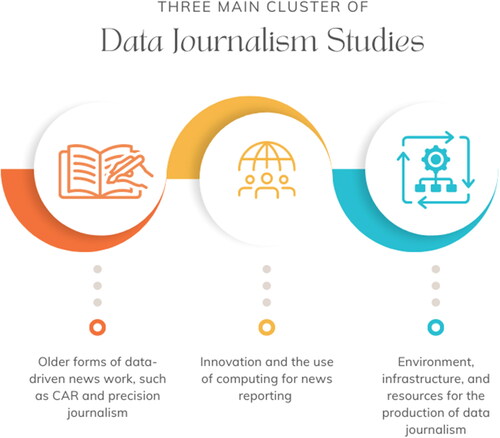

The scholarly literature describes data journalism as a practice that democratizes data literacy and provides tools that enable individual critical thinking (Gray, Gerlitz, and Bounegru Citation2018), which is in line with the mission of journalism as a fourth power (Larrondo-Ureta and Ferreras-Rodríguez Citation2021). In recent years, data journalism scholarship has witnessed a massive spike in production. These studies can be viewed in three major clusters (Jamil Citation2021).

The first cluster includes studies demonstrating the relationship between older forms of data-driven news work, such as computer-assisted reporting (CAR) and precision journalism, and the early phase of data journalism (Coddington Citation2015; Parasie and Dagiral Citation2013; Royal Citation2010). The second cluster is centered on innovation and the use of computing for news reporting (Anderson Citation2013; Flew et al. Citation2012; Gynnild Citation2014; Karlsen and Stavelin Citation2014). Finally, the third cluster takes into consideration the environment, infrastructure, and resources for the production of data journalism (Borges-Rey Citation2016; Fink and Anderson Citation2015; Knight Citation2015; Lewis and Usher Citation2013; Tabary, Provost, and Trottier Citation2016). provides a summary of them.

These clusters of studies are relevant to journalistic business models and collaborations as they provide insights into the different approaches and strategies that news organizations can adopt to produce data-driven storytelling. For example, news outlets may need to invest in computing and technological resources (e.g., tools and specialized staff) to enable data journalism, or collaborate with other organizations to access data sources and expertise. Additionally, understanding the relationship between different forms of data-driven news work can inform business models that combine different approaches for optimal impact.

In accordance with this, data journalism serves not only to increase the use and uptake of data that new technologies bring about and the opening up of public data (Weber, Engebretsen, and Kennedy Citation2018), but also to increase the number of people who are able to understand data and visual information (Gray, Gerlitz, and Bounegru Citation2018). More recently, studies on data journalism were expanded beyond the Western context (Mutsvairo, Bebawi, and Borges-Rey Citation2019), in defense of the idea that the practice is not restricted to wealthy countries and organizations. Therefore, data journalism is described as an asset in modernizing journalism and finding “new stories that could not be told without the analysis and visualization of data” (Weber, Engebretsen, and Kennedy Citation2018, 197). This has resulted in an amplification of data journalism in some news outlets’ organizational structures worldwide from a niche practice to a mainstream one (Rogers Citation2021).

In recent years, there has been growing concern about the credibility of news media, with many people expressing skepticism about the accuracy and impartiality of news reporting. Data journalism, therefore, brings the promise of increased transparency and openness by providing readers with access to the data sources and methods used in their reporting as a way for news organizations to regain the public’s trust and maintain their crucial societal role in society (Lesage and Hackett Citation2014; Lewis and Usher Citation2013; Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019).

Practitioners are also motivated to create new content to address some of the longstanding concerns about journalism’s failures and shed light on stories that people would otherwise be left without adequate information to make informed decisions about. By doing so, news organizations can ultimately lead to increased engagement and loyalty among readers, which can translate into greater revenue opportunities for news organizations (Howard Citation2014). This is also associated with the value proposition of news organizations, as it suggests that data journalism can help them to differentiate themselves from competitors by offering a more transparent and trustworthy approach to news reporting (Diakopoulos and Koliska, Citation2017).

However, in the studies included in this review, a common theme that emerged was the challenges that news organizations faced in incorporating data journalism into their business models. From the perspective of practitioners, facilitating the production of data journalism is seen as expensive and requires inter-institution-level factors (Zhang and Chen Citation2022), which include time, technological tools, manpower, and legal resources (Fink and Anderson Citation2015).

Furthermore, to achieve this engagement and loyalty among readers, organizations must understand the value of data journalism in producing quality content that meets public interests (Usher Citation2017). In other words, the collection of products and services that a news organization offers should meet the needs of its audiences (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010). Thus, data journalism often requires collaboration with the public. In fact, audience collaboration has become increasingly important for data-driven investigations, as it allows journalists to tap into the expertise and resources of people with diverse skills and knowledge. For example, news outlets collaborate with their audience is by using crowdsourcing techniques to collect and analyze data (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019). For example, a news organization may ask its readers to contribute information or share their personal experiences related to a particular analysis, which can then be used to inform illustrate data-driven reporting (Howard Citation2014).

Collaboration can take other forms, such as partnerships between newsrooms, joint investigations between journalists and experts, and collaborations with other industries and organizations (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2021; Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019; Lück and Schultz Citation2019). Moreover, collaboration can be particularly important in data journalism, as it often requires specialized skills and resources that are not available within a single organization. This lack of resources is the result of an absence of revenue streams that would ensure funds and long-term investments for creating powerful data journalism stories, streamlining business processes, and identifying new products and services for audiences (De Maeyer et al. Citation2015). While some argue that organizations are investing in expensive and investigative beats despite lacking resources, philanthropic foundations play a significant role in providing hundreds of thousands of dollars annually to specific organizations to promote particular news agendas (Wright, Scott, and Bunce Citation2019). Additionally, large and well-resourced news outlets also invest in specialized beats to produce high-quality news and earn recognition for their organizations. Despite these circumstances, many organizations fail to recognize the potential of data-driven stories for their business models. Consequently, the lack of interest affects practitioner efficiency and the frequency with which data stories are produced (Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020), which reveals that there are key activities that should be undertaken to develop data journalism projects.

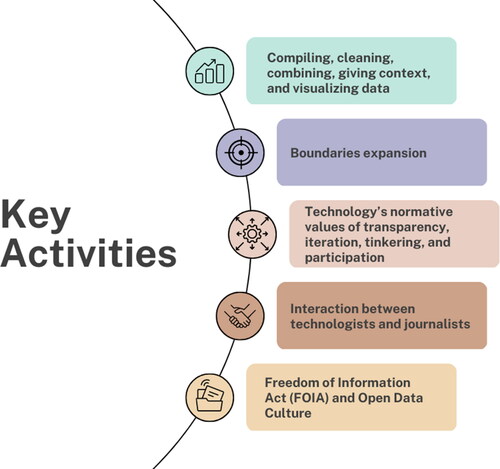

Revealing the Key Activities That Pushed Databases from Being a Novel to an Essential Resource for News Organizations

Although data journalism does not necessarily have visual information, data visualization is used to visually represent empirical evidence, which became a driving force of data-driven storytelling. According to practitioners that Weber, Engebretsen, and Kennedy (Citation2018) interviewed, “visual data stories are more attractive than text-based stories” (199) based on their click-through rates. However, these aesthetics are followed by multimodal artifacts that in general transgress the normal boundaries of journalism (Usher Citation2017). The tasks of compiling, cleaning, combining, and giving context for data were not part of the normal scope of the work of journalists. These activities now play an important role in the ad hoc construction of data stories and have become integrated into the practice. To achieve this, data journalists expanded their boundaries under the influence of stakeholders who were not previously a part of news production (Lewis and Usher Citation2013). This means that journalists have also had to shift their image from that of lone wolves to collaborators (Heft Citation2021).

Lewis and Usher (Citation2014) draw on Galison’s (Citation1997) trading zone concept to examine how the global network Hacks/Hackers serves as a space for interaction between technologists and journalists. The authors define technologists as professionals with expertise in technology, including software developers, computer programmers, and other professions often referred to as “hackers” (p. 385). In their study, the authors showed how the institutional support that Hacks/Hackers provided has led to the formation of relationships between different actors. However, these activities appear to be “dependent in part on the commitment and social connections of key individuals who orchestrate meetings and encourage these two groups to coordinate” (Lewis and Usher Citation2014, 390). Through working collaboratively, journalists learned to embrace the open-source culture—“as a structural framework of distributed development and a cultural framework”—carried by these technologists (Lewis and Usher Citation2013, 602).

Technologists produce source code that is freely distributed, as well as tools that can be accessed and modified, which allows it to scale quickly through copying or building upon others’ work. This is an essential component of data journalism, which relies on technology’s normative values of transparency, iteration, tinkering, and participation to produce and tell data-driven stories. In other words, data presents opportunities for reconsidering the epistemologies of journalism, ultimately influencing the production and distribution of news (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015). In particular, some of these values were not widely adopted in traditional journalism, as the industry suffered financially from the lack of a clear business model, which left little room for trial and error (Lewis and Usher Citation2013). Thus, open-source journalism came to be considered by many as a strategy for accomplishing innovation.

This journalism transparency and openness, in turn, inspired the open-source culture to make publicly available its sources, interests, and methods, which might influence not only the information presented, but also how the public interprets and perceives potential bias in the analysis (Lesage and Hackett Citation2014). For this reason, practitioners encouraged readers to explore the data themselves by providing a link to the raw data used in the article and describing the methodology used (Tandoc and Oh Citation2017).

On the other hand, some concerns are surrounding open-source journalism. Lewis and Usher (Citation2013) point out its lack of scalability, re-creation of hierarchies, and unclear relationship with corporate entities (613). Lesage and Hackett (Citation2014) argue that the collection and interpretation of data, as well as the provision of user-friendly platforms for the production of news, represent an interesting business proposition, which has the potential to be monetized both in terms of databases and data applications. Thus, journalists are adapting to the information flows of global capitalism. Appelgren and Lindén (Citation2020) described two Swedish digital native data journalism startups, which could be described as service oriented, selling products to legacy media outlets that did not have competencies and experience with the deployment of data stories. However, these organizations had to offer alternative products, such as event organizing, consultancy work, and content syndication, and seek out non-journalistic customers, due to the lack of commercial interest among Swedish newsrooms (Appelgren and Lindén Citation2020). In fact, Dick (Citation2014) found that the availability of data does not drive decision-making in interactive data stories, but budgetary constraints affect practice and limit the potential of the field.

In regards to the openness of data, this is a scenario that also influences the key activities of data journalism. Some data are considered more newsworthy than others, requiring data journalists to decide which is more relevant (Dick Citation2014). However, this is not a global scenario. While some countries have a wide range of open datasets and legislations such as Freedom of Information Acts (FOIA) have come into existence, others struggle to access data (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021; Jamil Citation2021; Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019). Data is the raw material of data journalism, and in places where it does not exist, practitioners have to construct their own datasets. Scholars reported the strong influence of data journalism on the open data movement in many countries, such as Argentina (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019) and Italy (Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019). Data journalists are a part of these efforts to re-figure the field by advocating and working with public institutions to promote general access to public data. Again, Hacks/Hackers was at the core of the journalism-related open data community, and sought new forms of government that could make data available through open data portals and application programming interfaces (APIs), as well as by pushing for better Freedom of Information (FOI) laws and enforcement (Lewis and Usher Citation2014). To some extent, these practitioners act to incorporate new organizational forms and experimental practice in their pursuit to shift the field’s organizational foundations, whom Hepp and Loosen (Citation2021) have defined as “pioneer journalists.”

Ultimately, budgetary constraints are one of the greatest impediments to the implementation of visual impact through interactives, infographics, charts, and maps. However, access to datasets has influenced the selection of visuals (Dick Citation2014; Stalph Citation2018; Tabary, Provost, and Trottier Citation2016; Young, Hermida, and Fulda Citation2018; Zamith Citation2019). In Cuba and the Dominican Republic, data journalists are creating their own databases due to the lack of open data portals and FOI laws (Trinidad Citation2020). A similar situation can be found in the Arab world, where “data are often not available or hard to access” (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021, 15). In India, as well, “open data requires [a] lot of processing before it can be used for analysis and interpretation” (Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020, 128). The low availability and inefficiency of accessing quality open data hinders the development of data journalism, making practitioners have to work together with their governments to promote open data and, where appropriate, to develop applications with re-used data and open government (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019; Tabary, Provost, and Trottier Citation2016; Zhang Citation2018). However, this is not the reality across the entire industry; previous studies have pointed out that elite media outlets in Western democracies did little original data collection (Knight Citation2015; Stalph Citation2018; Young, Hermida, and Fulda Citation2018; Zamith Citation2019), relying much more on governmental bodies and open data sources. As a result, most of their stories were about policy and political topics (Knight Citation2015; Stalph Citation2018; Zamith Citation2019).

Generally speaking, when the government provides data in the Global South, practitioners do not receive it in a machine-readable format, such as PDF or printed documents. A considerable amount of time and resources are devoted to converting such reports into a machine-readable format. Additionally, this process requires computational methods that are not always easily available to newsrooms (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021). Thus, building their own data or transforming non-machine-readable text into data have become necessary key activities and core competencies for producing data stories.

These activities, to a certain degree, contribute to the development of distinct epistemologies in data journalism. This is because they enhance data journalists’ skills in independently generating data, cultivate skepticism towards open data, and, as noted, motivate these practitioners to act as activists for open data movements (Cheruiyot and Ferrer-Conill Citation2018).

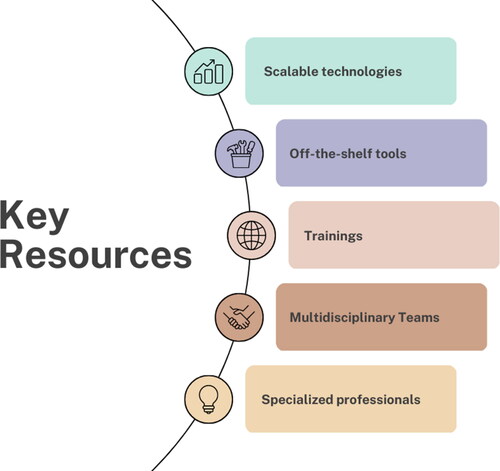

In summary, key activities for practitioners working on the production of data stories includes not only compiling, cleaning, combining, and giving context to data, but also working with other new actors, building datasets from scratch, or non-machine-readable text, and promoting the values of open-source culture in newsrooms. summarizes the key activities described in these articles. To achieve this, it is necessary to have available key resources (people and/or tools) in-house or to engage with reliable partners to manage the operations and complement these internal resources. Next, I discuss the tools and capabilities discussed in the literature that allow for the production of data stories at news outlets.

Key Resources: The Tools and Capabilities That Support the Sustainability and Longevity of the Production of Data Stories

Producing interactives can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, which usually requires contributions from subject-specialist journalists on large data projects. Due to the budgetary constraints the news industry faces, the “development and use of templates serve to despecialise the specialist” (Dick Citation2014, 495). This means the development of scalable technology, such as data visualization platforms (Usher Citation2017). Most newsrooms lack in-house tools for creating visuals to support the writing of data-driven stories (Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020). The absence of these skills in newsrooms has resulted in the creation of service-oriented, digital native sites that focus on selling news products to legacy media companies, which have also attracted non-journalistic customers (Appelgren and Lindén Citation2020).

In a different manner, some “news startups focus on creating products that they can then resell to other types of companies” (Usher Citation2017, 1126). In the data journalism field, a number of non-journalistic startups emerged to create easy-to-use tools that help practitioners create visuals that boost efficiency and help with their daily operations. These third-party tools, such as Carto, Flourish, Mapbox, and Tableau (de-Lima-Santos, Schapals, and Bruns Citation2021; Heravi et al. Citation2022), are usually referred to as out-of-the-box solutions, as they provide users with sophisticated capabilities designed to build effective, robust visualizations. These tools are intended to assist data journalists in their analysis, such as DocumentCloud, Tabula, and OpenRefine (Stray Citation2019). These companies act as pioneer journalism institutions that are helping to “realign or entangle journalistic practice with new media technologies” (Hepp and Loosen Citation2021, 578).

Smaller news outlets are more dependent on these tools, as they offer free trials or free versions, many of which can be set up quickly and are easy to use (Fink and Anderson Citation2015). Furthermore, in smaller news outlets it is common to find hybrid practitioners (Borges-Rey Citation2016), known as journo-coders, journo-devs, journalist-programmers, and programmer-journalists (Beiler, Irmer, and Breda Citation2020; Hannaford Citation2015; Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020; Parasie and Dagiral Citation2013), who are individual journalists who are responsible for more than one activity in the production of data-driven stories. In general, these professionals cannot specialize in one area because they have to carry out different tasks (Stalph Citation2020). This means that they have less time to dedicate to creating visuals or conducting in-depth analyses, but they have tools to help in these processes.

However, these practitioners have ended up “playing in someone else’s sandbox, according to their rules and whims” (Young, Hermida, and Fulda Citation2018, 127). In other words, these startups have their own business models, which include different value propositions and customer segments (de-Lima-Santos, Schapals, and Bruns Citation2021). In addition, many of these platforms do not offer ways to preserve data-driven stories, which poses risks to their long-term availability to the public (Broussard and Boss Citation2018). Furthermore, practitioners have mentioned that, in many cases, these “free tools restricted the scope of the stories they were producing” (Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020, 130). Thus, “[s]maller organizations were more susceptible to the limitations of third-party tools” (Fink and Anderson Citation2015, 477–478).

In contrast, larger organizations “had a greater ability to develop their own data tools, which they could improve and customize over time” (Fink and Anderson Citation2015, 477). In accordance with this, Weber, Engebretsen, and Kennedy (Citation2018) were able to identify some European newsrooms that were setting up their own system that allowed them to “employ narrative, explanatory, and argumentative techniques” (198), such as the scrollytelling format, that tends to follow a “Martini glass structure, first to tell the basic story in a linear way and then to open up the data visualization for exploration” (200). Consequently, these scalable products can be in-house solutions that are made available to professionals in these news organizations, allowing any individual to accurately produce data visuals for stories.

Thus, data journalism has brought new actors to the fore who have often taken on tasks and responsibilities that go beyond the traditional boundaries of journalism. Described as “news nerds” (Kosterich Citation2020), these new actors represent “new forms of professional journalists working in jobs at the intersection of traditional journalist positions and technologically-intensive positions” (p. 52). Multidisciplinary teams in newsrooms share a common organizational goal that tends to foster innovation (Westlund, Krumsvik, and Lewis Citation2021).

In a study by Hannaford (Citation2015), two legacy UK news organizations—the BBC and the Financial Times—were shown to rely on multidisciplinary teams composed of programmers, journalists, and designers who worked together to produce interactive data stories. Ananny and Crawford (Citation2015) identified these field-level institutional relationships that involve new actors as the “liminal press,” in which app designers “are working in a space between technology design and journalism, influenced by both but not entirely beholden to either as they create systems that gather, sort, rank, and circulate news” (Ananny and Crawford Citation2015, 204). Through multidisciplinary teamwork, these professionals can create architectures that use “crowd-sourced, participatory labor to do the work of news professionals” (Ananny and Crawford Citation2015, 204). Zhang and Chen (Citation2022), in regards to Hong Kong news outlets, have indicated that when more designers are involved in the news production process, there is a greater likelihood for organizations to adopt data-driven storytelling in their routine. However, this occurs most commonly in large, elite news outlets that can afford this division of labor through multidisciplinary teams (Fink and Anderson Citation2015).

These differing dynamics can result in new tensions in newsrooms caused by the interplay of data journalism between organizational structure and professional culture (Stalph Citation2020). Due to the highly stratified nature of data journalism, the necessary resources are segmented between resource-rich and resource-poor organizations (Fink and Anderson Citation2015). In this respect, the support, or “ancillary,” organizations, such as professional associations, training centers, foundations, and labs, have played a fundamental role in the dissemination of data journalism practices, with regards to cutting-edge training, and increasingly playing a supporting role in helping smaller news organizations to increase their competitiveness (Lowrey, Sherrill, and Broussard Citation2019). summarizes the key resources described in these articles.

Additionally, these collaborations play a major role not only in developing new skills but also in producing data-driven stories. Recent investigative projects have shed light on data journalism acting as a societal watchdog through collaborative efforts, such as the Panama Papers, Car Wash investigation (also known as Lava Jato in Latin America), Migrants Files investigation, and Lux Leaks (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2021; Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019; Lück and Schultz Citation2019). These projects relied on collaborative work to advance their goals, which constitutes another key aspect of the business model that should be considered when developing data journalism projects: the partner network. These emerging trends in the literature are discussed in detail in the next section.

Partner Network: Collaboration as an Essential Part of Data Journalism

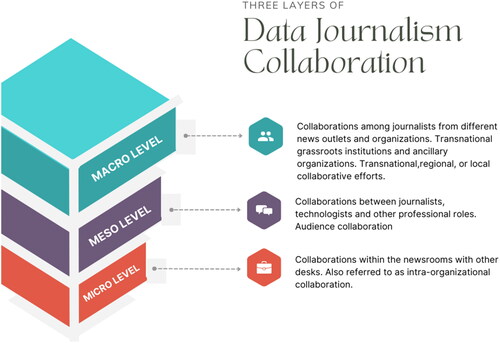

Therefore, this socio-discursive practice influences data journalism by increasing interaction among small groups and different actors to produce and promote data journalism pieces (De Maeyer et al. Citation2015). By doing so, data journalism has built its own collaborative infrastructures in some cases (Gray, Gerlitz, and Bounegru Citation2018), which has resulted in a change in the media ecology. Thus, intra- and inter-organizational interrelationships were created to stimulate collaboration between actors inside and outside the field (Hermida and Young Citation2017). The academic literature has examined the ways in which these collaborations have resonated within the field.

First, at a macro level, data journalism has resulted in continuous exchanges and collaborations between different news outlets and journalists (Trinidad Citation2020). Recent transnational collaborative efforts, such as the Football Leaks, Migrant Files, Lava Jato, Medicamentalia, NarcoData, and Panama Papers, have demonstrated a way for these at-times competing constituencies to find a middle ground (Larrondo-Ureta and Ferreras-Rodríguez Citation2021). These collaborative projects are distinct from “mere exchange arrangements through mutual and direct collaboration, shared interests and aims and mutual trust and consideration among members of the research team” (Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019, 1197). Through cooperation, these organizations have strengthened investigative journalism by overcoming their own difficulties, such as the lack of funding and appropriate tools for conducting these investigations. These joint efforts have also broadened the impact of their work by reaching a wider audience (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2021).

In general, these transnational journalism projects require massive amounts of computing power for data processing and sophisticated data analysis, which, consequently, demand professionals with considerable specialized skill sets, which are not commonly found in newsrooms (Larrondo-Ureta and Ferreras-Rodríguez Citation2021). Nevertheless, “highly institutionalized and integrated large-scale examples of cross-border collaborations, such as the Panama Papers, provide pioneering role models that can only partly be transferred to the broader field” (Heft and Baack Citation2022, 14). These extensive resources for the infrastructures required to maintain and coordinate collaboration are not easy to deploy on the organizational side, but provide considerable practical experience to practitioners taking this to other cross-national collaborations, for instance (Heft and Baack Citation2022). In addition, “frequent collaboration across countries can be read as a tendency toward internationalization” of the practice (Ausserhofer et al. Citation2020, 966).

Collaborations between newsrooms from countries can be viewed as both a trend toward internationalization and as a response to the global nature of the issues being studied. For instance, when investigating topics such as money laundering or tax evasion, the investigations are inherently international in scope (Larrondo-Ureta and Ferreras-Rodríguez Citation2021).

In this sense, collaborative efforts can also occur in other contexts, such as on a regional or local level. Cueva Chacón and Saldaña (Citation2021) examined the motivations for Latin American journalists to cooperate on investigative projects and found that, while safety is an important incentive to collaborate at the national level, it was not mentioned by practitioners who worked at the transnational level. Arias-Robles and López López (Citation2021) found that the UK local media compensate for the lack of resources by working in collaborative networks. These findings suggest that social, cultural, and economic differences in the various organizations and their countries affect collaborative efforts in journalism. These characteristics also impact the types of alliances formed between these organizations (Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019).

Traditionally, collaborative journalism has been perceived as cooperation between news organizations and journalists (Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019); however, these alliances are also formed among other types of organizations. (Baack Citation2018) revealed that data journalism triggered collaboration between civic tech institutions and news outlets. For example, the German Open Knowledge chapter has worked on several projects with the local newspaper Heilbronn Stimme. In Africa, these civic tech organizations are credited with “promoting and helping to establish data journalism in newsrooms through training, fellowships, and the development of flagship projects” (Cheruiyot, Baack, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2019, 1123).

In the United States, Lowrey, Sherrill, and Broussard (Citation2019) pointed out that, for the development of data journalism skills, ancillary organizations are important, such as “professional membership associations, trade groups, professional training centers, labs, foundations and academic programs” (2131). Ancillary organizations are involved in governing and implementing change within the social space. In the realm of data journalism, there is a negotiation of boundaries with other adjacent spaces, including computer science, academic research, government offices, and philanthropic foundations. The category of ancillary organizations in Western journalism industry encompasses notable examples, such as the Online News Association, WAN-IFRA, Investigative Reporters and Editors (IRE), and certain journalism schools. This aid also comes in the form of capital from foundations and tech companies, which invest in the development of data journalism tools and training for these professionals, such as the European Journalism Centre, Google News Labs, and the Knight Foundation. In the Arab region, ancillary organizations—such as the Access to Knowledge for Development Center (A2K4D), the Global Investigative Journalism Network, and the United Nations Development Programme (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021)—conducted the first data journalism conference.

From a second perspective, at the meso level, the transnational grassroots organization of Hacks/Hackers was instrumental in the facilitation of collaborative projects and activities that helped to disseminate this model (Lewis and Usher Citation2014). Even this level of cross-understanding appears to be dependent in part on the commitment and social connections of key individuals who orchestrate meetings and encourage collaboration; Hacks/Hackers proposed that cooperative works can overstep the boundaries of journalism by introducing technologists to the news industry. In a way, “collaborations between journalists, technologists and other professional roles are challenging or perhaps stretching existing journalistic norms” (Appelgren Citation2018, 308–309) and values. For example, data journalists from the United Kingdom work with programmers or graphic designers from outside the newsroom to make up for “the absence of certain advanced computational skills” (Borges-Rey Citation2016, 12).

Technologists reinvigorated “newswork in a way that moves beyond merely thinking about newsroom economics and gets to the heart of newsroom philosophy” (Lewis and Usher Citation2013, 614–615) by exposing news media practitioners to the “values of iteration, tinkering, transparency, and participation” (615). These new actors, commonly referred to as “news nerds,” reshaped the profession’s culture and values by introducing to newsrooms professionals who work at the intersection of traditional journalism and technologically intensive sectors (Kosterich Citation2020). Technologists espouse this collaborative mindset, which underpins much of the open-source culture (Lewis and Usher Citation2013, 602) that has become an essential part of newsrooms all over the world. Thus, these actors brought to the fore questions of what journalism is and how it should be developed in the digital age (Carlson Citation2018). That is why many saw these actors as a threat to journalism (Usher Citation2017).

Similarly, the audience collaboration has grown in significance for data-driven investigations, as it offers journalists access to a broader range of skills and knowledge. For example, the Argentine legacy news organization La Nación experimented with civic journalism using a public-oriented model in which audience participation occurred during the pre-production and production stages. For instance, “volunteers released and published 4,800 verified public documents in real-time” (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019, 1281) via a platform the data team developed. As official data is scarce about the marginalized people living in the favelas, and its use (and non-use) often serves to perpetuate historical inequities, digital news outlets based in these neighborhoods in Brazil work with non-profit organizations and the public to produce their own data to fill the gaps in official data (de-Lima-Santos and Mesquita Citation2023). Apart from collaborating with their audiences via crowdsourcing, where public data is collected and analyzed, news organizations can also involve the public in their stories by requesting them to submit information or share their personal experiences relevant to a particular analysis (Howard Citation2014).

And, third, the collaboration also happens within the newsroom (Appelgren and Salaverría Citation2018; Borges-Rey Citation2016; De Maeyer et al. Citation2015; Kashyap, Bhaskaran, and Mishra Citation2020), the micro level (see ). It can be applied to distinct functions and business units, which is also referred to as intra-organizational collaboration (Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019). Through cooperation, technologists, for instance, “complement the efforts of other newsworkers within their organizations” (Boyles Citation2020, 339). In large news organizations, data journalists tended to work collaboratively in teams with varying formal education, such as “statistics, computer science, and graphic design” (Fink and Anderson Citation2015, 472). As Stalph (Citation2020) argues, “[w]hereas highly professionalised staff does not necessarily require high degrees of formalisation, collaboration came to be a tacitly imposed rule” (7). In contrast, data journalists from smaller new outlets tended to be isolated, or working alone, but working with other business units and news desks (Beiler, Irmer, and Breda Citation2020). For example, African practitioners saw data journalism as a chance to work with their colleagues to uncover stories that are otherwise hidden from the public (Munoriyarwa Citation2022).

In fact, collaborative journalism data-driven stories may not necessarily resemble traditional archetypal data journalism (Stalph Citation2020). By working together with other actors, these stories are multidisciplinary and can cover all kinds of subjects, from health stories to migration ones (Risam Citation2019), prepared without or with minimalist visuals, aiming to simplify complex stories and huge data troves.

At the same time, these structures create additional layers of management in news organizations that become more complex over the course of time, which in some cases results in data teams that are independent from the rest of the newsroom (Boyles and Meyer Citation2017). This poses a potential risk to the cooperative efforts in the news outlets, as peers come to view the data and interactive teams as service desks (Dick Citation2014; Fink and Anderson Citation2015). These internal organizational constraints act as limitations not only to establishing a partner network but also to the production of data stories (Stalph Citation2020).

On the other hand, collaborations have led to major industry recognition. On average, the majority of nominees to the Global Editors Network’s data journalism award for the 2013 and 2014 editions had just over five individuals as authors or contributors, illustrating that cooperation is occurring to produce data stories (Loosen, Reimer, and De Silva-Schmidt Citation2020). However, this is uncommon. In an analysis of Canadian award-winning data journalism projects, Young, Hermida, and Fulda (Citation2018) found that submissions from one or two-person teams were predominant, in contrast with Loosen, Reimer, and De Silva-Schmidt (Citation2020) findings. Stalph (Citation2018), who examined daily data stories, had similar findings. His results suggest that more than half of all stories analyzed were authored by one journalist, and big collaborative data projects edited by large teams were exceptions. These studies indicate that there is no pattern of convergence in collaborative data projects among world news organizations.

Conclusion and Research Agenda

The first aim of this review study was to clarify the entanglements among data journalism, collaboration, and business models (RQ1). In general, data journalism scholarship uses qualitative methods to study these phenomena. There is little evidence of how news outlets are deploying data journalism in their business models. Findings also suggest the importance of collaborative approaches in the production of data journalism. However, there is a gap in the literature on how news organizations integrate cooperative modes of work into their business infrastructure.

The scholarly literature has examined the different activities, resources, and modes of work related to data journalism. In this aspect, much of technologists’ culture is being adopted to create a sharing and collaborative space, allowing news organizations to work with internal and external actors. New values, such as transparency, iteration, tinkering, and participation, emerge in this space to produce and tell data-driven stories. While these new approaches bring new arrangements, scholars draw attention to the fact that open-source journalism lacks scalability, re-creates hierarchies, and has an unclear relationship with corporate entities (Lewis and Usher Citation2013). Thus, key activities include convincing their peers of the importance of data journalism as part of the news outlets’ value proposition to produce quality journalism that meets public interest (Usher Citation2017).

Besides this, practitioners need to work with public entities and non-governmental organizations to obtain information that can serve as necessary input for their data-driven stories. As data is the raw material for data journalism, in order to build their own datasets (Trinidad Citation2020), practitioners have to overcome national and local limitations for open data and FOI requests (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021; Jamil Citation2021; Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019). On the other hand, data journalists have worked with their governments to promote open data, such as in Argentina (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019) and Italy (Porlezza and Splendore Citation2019).

Another key activity the literature revealed is the production of visuals and interactive elements for data stories. While time, technological tools, manpower, and legal resources influence newsroom decisions, datasets and skillsets have also influenced the selection of visuals (Dick Citation2014; Stalph Citation2018; Tabary, Provost, and Trottier Citation2016; Young, Hermida, and Fulda Citation2018; Zamith Citation2019). For example, in places where a considerable amount of time and resources are devoted to the transformation of data to a machine-readable format, there is less time to devote to producing visuals. In addition, whether the visuals require advanced computational skills, not all newsrooms have access (Fahmy and Attia Citation2021; Jamil Citation2021) and practitioners have to find external resources to help them.

This leads to an understanding of the resources required or available to produce data stories. The literature discusses a dichotomous approach to the development of data storytelling skills in newsrooms. While larger and well-resourced news outlets can have multidisciplinary data teams (Fink and Anderson Citation2015; Hannaford Citation2015), smaller organizations tend to have hybrid professionals who are responsible for the entire production pipeline of a data story (Borges-Rey Citation2016; Parasie and Dagiral Citation2013).

Hybrid practitioners do not have time to specialize in one field as they have to carry out different tasks (Stalph Citation2020), requiring them to resort to the use of third-party tools to produce data stories (Fink and Anderson Citation2015), which ranges from those used for analysis, such as DocumentCloud, Tabula, and OpenRefine (Stray Citation2019) to those used for the creation of visuals, such as Carto, Flourish, Mapbox, and Tableau (de-Lima-Santos, Schapals, and Bruns Citation2021; Heravi et al. Citation2022). While these resources are available to journalists, they also have certain limitations (Young, Hermida, and Fulda Citation2018, 127), which include a lack of ways for preserving data stories, endangering the availability of these stories to the public in the long term (Broussard and Boss Citation2018).

Therefore, well-resourced news outlets, that have multidisciplinary teams, offer in-house solutions that adapt to the needs of their organizations and are available to the professionals in these news organizations, allowing any person to produce visuals and guaranteeing the long-term existence and independence of data-driven stories (Ananny and Crawford Citation2015; Usher Citation2017; Weber, Engebretsen, and Kennedy Citation2018).

In another area, collaborative efforts are an integral part of data journalism (RQ2). By bringing together journalists and technologists (Lewis and Usher Citation2013), data journalists are experimenting with new ways of working and breaking down silos in order to collaborate across boundaries and reshape the profession’s culture and values (Lewis and Usher Citation2014). These collaborative networks start to gain form in these organizations through multidisciplinary teams composed of professionals with different backgrounds and that have evolved toward working with different institutions. Therefore, the partner network can consist of internal and external actors (Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019). The latter can be not only news outlets, but also civil society and non-governmental organizations, as well as ancillary institutions that promote data journalism (Baack Citation2018; Cheruiyot, Baack, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2019). The public can also become a part of this network, helping the workflow of data stories at news organizations (Palomo, Teruel, and Blanco-Castilla Citation2019).

Whereas the history and form of collaborative journalism and business models have been studied extensively, their entanglements with data journalism have received much less attention. This review, therefore, contains information accumulated over more than a decade of data journalism scholarship and through an effective logical structure that introduces and gradually builds upon key concepts in order to connect them. This work’s key contribution is providing an overview of these news organizations’ business models from an infrastructure perspective, that is, their key activities and resources, and partner network (Osterwalder and Pigneur Citation2010). In reviewing these articles, it was found that current data journalism scholarship addresses the collaborative and business model of the news organizations in a shallow way. These two topics are very much linked to data journalism and necessary to develop industry practice. From simple networks that exist inside news organizations to large cross-border, data-driven investigative projects, cooperative efforts are necessary to produce data-based products. However, it remains possible if only the key activities are defined and newsrooms offer the resources necessary to perform them.

Finally, from the perspective of collaboration, new research avenues are necessary for the future development of data journalism in the news industry (RQ3). Collaborative journalism and data journalism are two practices in the news industry that have gained traction in the last decades. However, there has been less previous evidence indicating how these two practices are interconnected. Few examples mentioned cross-national collaborations as data journalism projects, such as the Panama Papers, Car Wash investigation (also known as Lava Jato in Latin America), Migrants Files investigation, and Lux Leaks (Cueva Chacón and Saldaña Citation2021; Heft, Alfter, and Pfetsch Citation2019; Lück and Schultz Citation2019). However, smaller-scale collaborative projects might also rely on data and computational approaches to generate news products. Therefore, future research could explore the other nuances of data journalism collaboration.

In addition, very little is known about data journalism outside of the news desks of early-adopter organizations. Many researchers have studied award-winning news organizations by analyzing the content of their data projects. It would be interesting to conduct ethnographic studies and in-depth interviews with professionals that work in these organizations to better understand their best practices and find out what lessons they have learned. In particular, that would make it easier for small and medium-sized news organizations to adopt these approaches on a small scale and in their own contexts. Nowadays, one of the journalists’ key activities is the production of content for social media platforms, but little is known about how these practitioners are adapting data stories to these environments, where the economy of attention reigns supreme. Thus, research about mobile and social media data journalism is welcomed. Furthermore, it would be interesting to understand how the public views data journalism as part of the value that news organizations offer in terms of producing quality journalism that meets its interests.

Another issue this study raised is the dichotomy between multidisciplinary data teams and hybrid professionals. As Ausserhofer et al. (Citation2020) stressed, in journalism research, “there is a strong connection between the research interest, the chosen theory, the methods of data collection and analysis, and the reporting of results” (967). Instead of adopting one of these approaches, are news outlets adopting a combination of them? Further research could explore this possibility.

While several articles have analyzed the epistemology of data journalism, few have specifically focused on the epistemological challenges related to collaboration. To gain a better understanding, future research could investigate this. Additionally, it would be valuable to explore how data journalists navigate the cultural differences between themselves and technologists, and how this impacts their ability to collaborate effectively. It would also be interesting to investigate how external factors such as limitations imposed by news organizations or the absence of FOI laws may affect the practice of data journalism.

In addition to the above-mentioned research gaps, data journalism research currently has little to say about media management. It is important to understand how data journalism can be integrated into the different layers of news organizations’ business models. Who are the main partners in collaborative, data-driven projects? How can data journalism become sustainable in newsrooms? It is important to continue investigating how data journalism combines these aspects in a systematic way.

This review was limited to articles in which data journalism was associated with “collaborative” and “business models.” However, researchers could refer to these terms with other labels, which were out of the scope of this review, such as “networks” and “strategies.” Since these terms are infrequently employed in data journalism literature, they were not included in the literature review. Future systematic reviews could focus on one of these aspects and include more labels to better understand the nuances of how data journalism is studied across the globe.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ananny, M., and K. Crawford. 2015. “A Liminal Press: Situating News App Designers within a Field of Networked News Production.” Digital Journalism 3 (2): 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.922322

- Anderson, C. W. 2013. “Towards a Sociology of Computational and Algorithmic Journalism.” New Media & Society 15 (7): 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812465137

- Appelgren, E. 2018. “An Illusion of Interactivity.” Journalism Practice 12 (3): 308–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1299032

- Appelgren, E., and C. G. Lindén. 2020. “Data Journalism as a Service: Digital Native Data Journalism Expertise and Product Development.” Media and Communication 8 (2): 62–72. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v8i2.2757

- Appelgren, E., and R. Salaverría. 2018. “The Promise of the Transparency Culture: A Comparative Study of Access to Public Data in Spanish and Swedish Newsrooms.” Journalism Practice 12 (8): 986–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2018.1511823

- Arias-Robles, F., and P. J. López López. 2021. “Driving the Closest Information. Local Data Journalism in the UK.” Journalism Practice 15 (5): 638–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2020.1749109

- Ausserhofer, J., R. Gutounig, M. Oppermann, S. Matiasek, and E. Goldgruber. 2020. “The Datafication of Data Journalism Scholarship: Focal Points, Methods, and Research Propositions for the Investigation of Data-Intensive Newswork.” Journalism 21 (7): 950–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917700667

- Baack, S. 2018. “Practically Engaged: The Entanglements between Data Journalism and Civic Tech.” Digital Journalism 6 (6): 673–692. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1375382

- Beiler, M., F. Irmer, and A. Breda. 2020. “Data Journalism at German Newspapers and Public Broadcasters: A Quantitative Survey of Structures, Contents and Perceptions.” Journalism Studies 21 (11): 1571–1589. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2020.1772855

- Bhimani, H., A. L. Mention, and P. J. Barlatier. 2019. “Social Media and Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Directions.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 144: 251–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.10.007

- Borges-Rey, E. 2016. “Unravelling Data Journalism: A Study of Data Journalism Practice in British Newsrooms.” Journalism Practice 10 (7): 833–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1159921

- Boyles, J. L. 2020. “Deciphering Code: How Newsroom Developers Communicate Journalistic Labor.” Journalism Studies 21 (3): 336–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1653218

- Boyles, J. L., and E. Meyer. 2017. “Newsrooms Accommodate Data-Based News Work.” Newspaper Research Journal 38 (4): 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739532917739870

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2012. “Thematic Analysis.” In APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological, edited by H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher, 57–71. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Broussard, M., and K. Boss. 2018. “Saving Data Journalism.” Digital Journalism 6 (9): 1206–1221. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1505437

- Carlson, M. 2018. “Boundary Work.” In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, edited by T. P. Vos, F. Hanusch, D. Dimitrakopoulou, M. Geertsema-Sligh, & A. Sehl, 1–6. Hoboken: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0035

- Carson, A., and K. Farhall. 2018. “Understanding Collaborative Investigative Journalism in a “Post-Truth” Age.” Journalism Studies 19 (13): 1899–1911. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2018.1494515

- Cheruiyot, D., S. Baack, and R. Ferrer-Conill. 2019. “Data Journalism beyond Legacy Media: The Case of African and European Civic Technology Organizations.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1215–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1591166

- Cheruiyot, D., and R. Ferrer-Conill. 2018. “Fact-Checking Africa”: Epistemologies, Data and the Expansion of Journalistic Discourse.” Digital Journalism 6 (8): 964–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1493940

- Coddington, M. 2015. “Clarifying Journalism’s Quantitative Turn.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976400

- Cueva Chacón, L. M., and M. Saldaña. 2021. “Stronger and Safer Together: Motivations for and Challenges of (Trans)National Collaboration in Investigative Reporting in Latin America.” Digital Journalism 9 (2): 196–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1775103

- de-Lima-Santos, M. F., and L. Mesquita. 2023. “Data Journalism in Favela: Made by, for, and about Forgotten and Marginalized Communities.” Journalism Practice 17 (1): 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1922301

- de-Lima-Santos, M. F., A. K. Schapals, and A. Bruns. 2021. “Out-of-the-Box versus in-House Tools: How Are They Affecting Data Journalism in Australia?” Media International Australia 181 (1): 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X20961569

- Diakopoulos, N., and M. Koliska. 2017. “Algorithmic Transparency in the News Media.” Digital Journalism 5 (7): 809–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1208053.

- De Maeyer, J., M. Libert, D. Domingo, F. Heinderyckx, and F. Le Cam. 2015. “Waiting for Data Journalism.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 432–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976415

- Dick, M. 2014. “Interactive Infographics and News Values.” Digital Journalism 2 (4): 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2013.841368

- Fahmy, N., and M. A. majeed Attia. 2021. “A Field Study of Arab Data Journalism Practices in the Digital Era.” Journalism Practice 15 (2): 170–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1709532

- Fink, K., and C. W. Anderson. 2015. “Data Journalism in the United States: Beyond the “Usual Suspects.” Journalism Studies 16 (4): 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2014.939852

- Flew, T., C. Spurgeon, A. Daniel, and A. Swift. 2012. “The Promise of Computational Journalism.” Journalism Practice 6 (2): 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2011.616655

- Galison, P. 1997. Image and logic : a material culture of microphysics. 1st ed. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/I/bo3710110.html

- Gray, J., C. Gerlitz, and L. Bounegru. 2018. “Data Infrastructure Literacy.” Big Data & Society 5 (2): 205395171878631. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951718786316

- Gynnild, A. 2014. “Journalism Innovation Leads to Innovation Journalism: The Impact of Computational Exploration on Changing Mindsets.” Journalism 15 (6): 713–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884913486393

- Hannaford, L. 2015. “Computational Journalism in the UK Newsroom.” Journalism Education 4 (1): 6–24.

- Heft, A. 2021. “Transnational Journalism Networks “from below”. Cross-Border Journalistic Collaboration in Individualized Newswork.” Journalism Studies 22 (4): 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2021.1882876

- Heft, A., B. Alfter, and B. Pfetsch. 2019. “Transnational Journalism Networks as Drivers of Europeanisation.” Journalism 20 (9): 1183–1202. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917707675

- Heft, A., and S. Baack. 2022. “Cross-Bordering Journalism: How Intermediaries of Change Drive the Adoption of New Practices.” Journalism 23 (11): 2328–2346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884921999540

- Hepp, A., and W. Loosen. 2021. “Pioneer Journalism: Conceptualizing the Role of Pioneer Journalists and Pioneer Communities in the Organizational Re-Figuration of Journalism.” Journalism 22 (3): 577–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884919829277

- Heravi, B., K. Cassidy, E. Davis, and N. Harrower. 2022. “Preserving Data Journalism: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journalism Practice 16 (10): 2083–2105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1903972

- Hermida, A., and M. L. Young. 2017. “Finding the Data Unicorn.” Digital Journalism 5 (2): 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2016.1162663

- Higgins, J. P. T., D. G. Altman, P. C. Gotzsche, P. Juni, D. Moher, A. D. Oxman, J. Savovic, K. F. Schulz, L. Weeks, and J. A. C. Sterne, Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. 2011. “The Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for Assessing Risk of Bias in Randomised Trials.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 343 oct18 (2): D 5928. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Howard, A. B. 2014. The Art and Science of Data-Driven Journalism. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University. https://doi.org/10.1360/zd-2013-43-6-1064

- Iden, J., L. B. Methlie, and G. E. Christensen. 2017. “The Nature of Strategic Foresight Research: A Systematic Literature Review.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 116: 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.002

- Jamil, S. 2021. “Increasing Accountability Using Data Journalism: Challenges for the Pakistani Journalists.” Journalism Practice 15 (1): 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2019.1697956

- Karlsen, J., and E. Stavelin. 2014. “Computational Journalism in Norwegian Newsrooms.” Journalism Practice 8 (1): 34–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2013.813190

- Kashyap, G., H. Bhaskaran, and H. Mishra. 2020. “We Need to Find a Revenue Model”: Data Journalists’ Perceptions on the Challenges of Practicing Data Journalism in India.” Observatorio (OBS*) 14 (2): 121–136. https://doi.org/10.15847/obsOBS14220201552

- Knight, M. 2015. “Data Journalism in the UK: A Preliminary Analysis of Form and Content.” Journal of Media Practice 16 (1): 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682753.2015.1015801

- Kosterich, A. 2020. “Managing News Nerds: Strategizing about Institutional Change in the News Industry.” Journal of Media Business Studies 17 (1): 51–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1639890

- Larrondo-Ureta, A., and E.-M. Ferreras-Rodríguez. 2021. “The Potential of Investigative Data Journalism to Reshape Professional Culture and Values. A Study of Bellwether Transnational Projects.” Communication & Society 34 (1): 41–56. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.34.1.41-56

- Lesage, F., and R. A. Hackett. 2014. “Between Objectivity and Openness—the Mediality of Data for Journalism.” Media and Communication 2 (2): 42–54. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v2i2.128

- Lewis, S. C., and N. Usher. 2013. “Open Source and Journalism: Toward New Frameworks for Imagining News Innovation.” Media, Culture and Society 35 (5): 602–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443713485494

- Lewis, S. C., and N. Usher. 2014. “Code, Collaboration, and the Future of Journalism: A Case Study of the Hacks/Hackers Global Network.” Digital Journalism 2 (3): 383–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.895504

- Lewis, S. C., and O. Westlund. 2015. “Big Data and Journalism: Epistemology, Expertise, Economics, and Ethics.” Digital Journalism 3 (3): 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.976418

- Loosen, W., J. Reimer, and F. De Silva-Schmidt. 2020. “Data-Driven Reporting: An on-Going (r)Evolution? An Analysis of Projects Nominated for the Data Journalism Awards 2013–2016.” Journalism 21 (9): 1246–1263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917735691

- Lowrey, W., L. Sherrill, and R. Broussard. 2019. “Field and Ecology Approaches to Journalism Innovation: The Role of Ancillary Organizations.” Journalism Studies 20 (15): 2131–2149. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2019.1568904

- Lück, J., and T. Schultz. 2019. “Investigative Data Journalism in a Globalized World.” Journalism Research 2 (2): 93–114. https://doi.org/10.1453/2569-152X-22019-9858-en

- Mohamed Shaffril, H. A., S. F. Samsuddin, and A. Abu Samah. 2021. “The ABC of Systematic Literature Review: The Basic Methodological Guidance for Beginners.” Quality & Quantity 55 (4): 1319–1346. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01059-6

- Mongeon, P., and A. Paul-Hus. 2016. “The Journal Coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A Comparative Analysis.” Scientometrics 106 (1): 213–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Munoriyarwa, A. 2022. “Data Journalism Uptake in South Africa’s Mainstream Quotidian Business News Reporting Practices.” Journalism 23 (5): 1097–1113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884920951386

- Mutsvairo, B. 2019. “Challenges Facing Development of Data Journalism in Non-Western Societies.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1289–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1691927

- Mutsvairo, B., S. Bebawi, and E. Borges-Rey. 2019. Data Journalism in the Global South, edited by B. Mutsvairo, S. Bebawi, & E. Borges-Rey, 1st ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25177-2

- Osterwalder, A., and Y. Pigneur. 2010. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers. 1st ed. Wiley.

- Palomo, B., L. Teruel, and E. Blanco-Castilla. 2019. “Data Journalism Projects Based on User-Generated Content. How La Nacion Data Transforms Active Audience into Staff.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1270–1288. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1626257

- Parasie, S., and E. Dagiral. 2013. “Data-Driven Journalism and the Public Good: “Computer-Assisted-Reporters” and “Programmer-Journalists” in Chicago.” New Media & Society 15 (6): 853–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812463345

- Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. Mackenzie, D. G. Bachrach, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2005. “The Influence of Management Journals in the 1980s and 1990s.” Strategic Management Journal 26 (5): 473–488. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.454

- Porlezza, C., and S. Splendore. 2019. “From Open Journalism to Closed Data: Data Journalism in Italy.” Digital Journalism 7 (9): 1230–1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1657778

- Risam, R. 2019. “Beyond the Migrant “Problem”: Visualizing Global Migration.” Television & New Media 20 (6): 566–580. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476419857679

- Rogers, S. 2021. “From the Guardian to Google News Lab: A Decade of Working in Data Journalism.” In The Data Journalism Handbook, edited by L. Bounegru & J. Gray, 2nd ed., 279–285. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048542079-039

- Royal, C. 2010. “The Journalist as Programmer: A Case Study of the New York Times Interactive News Technology Department.” In International Symposium in Online Journalism.

- Stalph, F. 2018. “Classifying Data Journalism: A Content Analysis of Daily Data-Driven Stories.” Journalism Practice 12 (10): 1332–1350. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1386583

- Stalph, F. 2020. “Evolving Data Teams: Tensions between Organisational Structure and Professional Subculture.” Big Data & Society 7 (1): 205395172091996. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720919964

- Stray, J. 2019. “Making Artificial Intelligence Work for Investigative Journalism.” Digital Journalism 7 (8): 1076–1097. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2019.1630289

- Tabary, C., A.-M. Provost, and A. Trottier. 2016. “Data Journalism’s Actors, Practices and Skills: A Case Study from Quebec.” Journalism 17 (1): 66–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884915593245

- Tandoc, E. C., and S. K. Oh. 2017. “Small Departures, Big Continuities?: Norms, Values, and Routines in the Guardian’s Big Data Journalism.” Journalism Studies 18 (8): 997–1015. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2015.1104260