Abstract

News organisations are growing increasingly dependent on digital infrastructures for the distribution of news, AI implementation, and management of data. In this article, we argue that this dependency goes beyond the level of platforms, reaching into the internet backbone infrastructures that transmit, peer, deliver and host data on which journalism relies. Using Norway as a case, we map the actors involved in the subsea cable sectors, internet exchange points, content delivery networks and the data centres and cloud services that traffic, store and process digital journalism. Given the private, foreign nature of most of the actors involved in these infrastructures, we ask how these backbone infrastructures create interdependencies for the news industries in terms of data sovereignty, distribution control and regulatory jurisdiction. We discuss journalism’s dependency on each of these infrastructural sectors using sociotechnical theory, the contribution to which is to extend the range at which platform capture is considered in journalism scholarship.

Introduction

The growing importance of artificial intelligence in the processing and distribution of digital journalism has drawn increasing attention to journalism’s dependence on platforms (Nielsen and Ganter Citation2022; Simon Citation2022), to the point where journalism is seen to experience a form of ‘capture’ (Nechushtai Citation2018) whereby news organisations become more and more reliant on technology giants like Meta, Google, and Amazon in their ability to reach audiences. Scholars have considered the role of platforms from a range of perspectives, including in assessing the opinion power of social media platforms (Helberger Citation2020), how they shape information ecosystems (Thorson et al. Citation2020), and how they gatekeep the news (Wallace Citation2018). Researchers have also investigated how platforms have become crucial in the production (e.g., Chua and Westlund Citation2022), circulation (Ratner, Dvir Gvirsman, and Ben-David Citation2023), and discoverability (Ivancsics et al. Citation2023) of news. This ‘platformisation’ of journalism (e.g., Hase, Boczek, and Scharkow Citation2023) has led some scholars to argue that we should pay more attention to the materiality of platforms (e.g., Chua Citation2023), as well as their infrastructural role (Pickard Citation2020), in considering the independence and autonomy of journalism (Kristensen and Hartley Citation2023) in the platform era.

While this attention to platforms sheds important light on the dependencies shaping news organisations, we argue that journalism scholarship does not go far enough in considering the range of infrastructure dependencies that concern journalism. The ‘infrastructure turn’ (Hesmondhalgh Citation2022), or the “infrastructuralism” (Peters Citation2015) of media and communication, has so far attracted little attention in journalism scholarship. However, the distribution of news relies on a host of infrastructure actors, beyond the platforms, that control the material resources for AI implementation and editorial decision-making. Digital infrastructures include the subsea fibre cables that traffic web content from news sites to audiences (e.g., enabling The Guardian to link to a New York Times story or a foreign .gov or .org website); the content delivery networks (CDNs) that are necessary for streaming live coverage, for instance from BBC World Service or CNN to users’ devices; the Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) that peer content between websites; and the data centres that house the cloud services that store, process, and manage the applications journalists use to produce the news, and that host the personal data of news users. These backbone services constitute the infrastructure for communication on which digital journalism relies – services that create interdependencies along the material, protocol, and application layers of journalism’s digital ecosystem.

Many of these core functions are controlled by the same actors that engage journalism in platform capture (Partin Citation2020). Hence, journalism’s dependency on Meta, Google and Microsoft reaches far beyond the platforms themselves and into the digital infrastructures that support communication on a critical scale – infrastructures that societies rely on for the free exchange of information (Fischli Citation2022). Meta owns data centres and subsea fibre cables that enable data flow and connectivity. Google alone controls 8,5% of subsea cables globally (Ball Citation2021). Furthermore, Google dominates the cloud market (together with Amazon Web Services) that offers the data processing and operability necessary to run newsroom applications and audience analytics (Kristensen and Hartley Citation2023). The global market leaders in content delivery networking services, Akamai, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon’s CloudFront, carry over 70% of internet traffic around the world (Ghaznavi et al. Citation2021), most of which is streamed video content – including live news and dynamic web content from news organisations. These infrastructure actors set the protocols for how news organisations’ data are managed and how journalistic content is distributed. Behind the ‘platforms’, these actors control key resources in the internet infrastructure that societies rely on for the exchange of information.

Investigating these infrastructures entails that we look beyond the familiar spaces of news production, distribution, and consumption that journalism scholarship typically engages with. Doing so has the potential to identify ongoing power struggles shaping the relationship between journalism and technology (Eldridge et al. Citation2021). Infrastructures are relevant to the study of digital journalism not least because internet backbone structures extend beyond borders (Flensburg and Lai Citation2020), and they are essentially unregulated in many countries. Here, scholars have encouraged more political economic investigations of infrastructure alignment in the journalism industries (e.g., Hesmondhalgh and Lotz Citation2020; Pickard Citation2022). This analysis thus aims to make a conceptual contribution to digital journalism studies by considering internet backbone structures as part of the infrastructure for news, thereby strengthening the political economic framework with which journalism can be studied. Key to this aim is to highlight how material power translates into political and social power (McChesney Citation2013), and how concentration within the communication industries (Winseck Citation2017) and the abuse of market power (Pickard Citation2013) may impact on democracy (Mosco Citation2009). The research questions informing this research are, RQ1: how do the backbone infrastructures of journalism create interdependencies; and RQ2: how do they shape data sovereignty, distribution control, and regulatory jurisdictions in the journalism industries?

We approach these questions through an actor-oriented study of the digital communication infrastructure in Norway, a country with near universal broadband access (93,6%) (Nkom Citation2023), extensive 5G rollout, and a digitally innovative journalism sector (Olsen, Kalsnes, and Barland Citation2021) whose data processing and distribution rely heavily on content delivery networks (e.g., Akamai), cloud services (e.g., Google Cloud), social media platforms (e.g., Facebook), and third-party services offering content management, distribution, and personalisation (Sjøvaag, Olsen, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024). At the same time, the backbone infrastructure of the internet in Norway is limited in scale and scope, enabling a comprehensive mapping. While the backbone markets are developing so quickly that it is impossible to establish more than a snapshot of developments (Sjøvaag and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024), such an infrastructure mapping (Flensburg and Lai Citation2020), can provide a fruitful entry point to extend the scope of dependencies that journalism faces in the digital communication ecosystem, operationalised here as data sovereignty, distribution control, and jurisdiction. The contribution here lies with embedding infrastructure dependencies into digital journalism – an overlooked aspect that serves to illuminate the political economic mechanisms that shape the autonomy of the news industries (Hesmondhalgh and Lotz Citation2020). Important here in particular is the lack of regulation (Just Citation2022) that allows the backbone communication infrastructure to evolve interdependent structures on which journalism relies for distribution and data processing.

Literature Review

Infrastructures are generally thought of as robust and reliable systems that are centrally controlled, widely accessible and ubiquitous, constituting essential services (Plantin et al. Citation2018) that are sometimes thought of as ‘invisible’ until they break down (Furlong Citation2021). In the digital realm, infrastructures include computing networks that allow a multitude of actors to organise their services, enabled by the ability of digital infrastructures to “collect, store, and make digital data available across a number of systems and devices” (Constantinides, Henfridsson, and Parker Citation2018, p. 382). Included in definitions of digital infrastructure are physical components like data warehouses, fibreoptic cables, server and computing facilities; digital components like software, operating systems and algorithms; human labour; and organisational structures that maintain and develop the infrastructures (Simon Citation2022). Shared standards and protocols also form infrastructures as they constitute technical power (Munn Citation2023) that mediate action (Bowker and Star Citation2000). While the concept of infrastructures relevant to media industries can carry some ‘definitional looseness’ (Hesmondhalgh Citation2022), journalism’s technical infrastructures can be thought of as “the material basis for communication [that] make up the underlying resources that communication markets and policies revolve around” (Flensburg and Lai Citation2020, p 695). We thus apply a material approach (see Frischmann Citation2012) whereby infrastructures are considered physical resources that enable and constrain critical functions in society. As journalism’s infrastructures consist of interdependent networks of modular technological architectures whose services are offered by a multitude of actors (Sjøvaag, Olsen, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024), this can be thought of as an ecosystem (see BEREC Citation2022). This ecosystem embodies the essential infrastructures that store, process and deliver the data that constitute journalistic products and services.

These dependencies entail distributed, technological infrastructures that introduce new actors into journalism’s ecosystem, shaping the autonomy of the networked press (e.g., Ananny Citation2018). At a macro level, beyond the basic notion that infrastructures determine how the public may access the news (Pickard Citation2020), public open data infrastructures shape national data journalism practices, widening the gap between information-rich and information-poor countries (Camaj, Martin, and Lanosga Citation2022). At the meso level, journalistic infrastructures are understood as sources located within a community (Napoli et al. Citation2017); as collaborative infrastructures that allow journalism to be shared in local communities (Wenzel and Crittenden Citation2023); as organisational frameworks for structured and data-driven journalism (Graves and Anderson Citation2020); and as the trust-building infrastructures news organisations set up to promote transparency, innovation and collaboration (Zamith Citation2023). At the micro level, newsroom infrastructures shape journalists’ daily practices (Chiumbu and Munoriyarwa Citation2023). Whereas Moran and Nechushtai (Citation2023) have suggested that notions such as trust should be considered a foundational infrastructure of journalism, we argue that an awareness of the material infrastructure that supports digital news circulation will help strengthen trust in its epistemic power (Carlson Citation2020).

Theoretical Framework

A dominant paradigm for understanding what infrastructures are is the sociotechnical perspective that considers the interplay between the norms and cultures of organisations on the social side and the mechanical, electric, and computational on the technical side. Sociotechnical theory thus accounts for the impact of infrastructure on organisational routines (Edwards et al. Citation2009), including how technical standards influence practice, binding media companies to data protocols, data compatibility requirements and governance rules (Bowker and Star Citation2000; Constantinides, Henfridsson, and Parker Citation2018). In digital journalism studies, sociotechnical theory has been used to understand technology changes in journalism, including cross-media news work (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015), computational journalism (Lischka, Schaetz, and Oltersdorf Citation2023), news discovery (Diakopoulos Citation2020), personalisation (Schjøtt Hansen and Hartley Citation2023), and AI integration (Gutierrez Lopez et al. Citation2023). The sociotechnical framework has thus primarily been mobilised to understand technology impacts on news work, while research has largely ignored the political economic aspects of infrastructure alignment.

Containing forms of power and authority (Winner Citation1980), infrastructures can be seen to possess agency, and can structure political constellations and enable autonomy (Huang and Mayer Citation2022). As more aspects of life become mediated by data, the capacities that communication infrastructures afford become strategic systems, making them political (Munn Citation2023). Data power is primarily distributed among the backbone infrastructures that enable data packet flows and the data centres and cloud services that provide storage. The actors in this infrastructure gain institutional power in the sense that they have regulatory control over data resources through governance rules of access, protocols, and functions (Huang and Mayer Citation2022). When the ‘infrastructural data power’ that this entails becomes intrinsic to decision-making, it subsequently becomes a factor in power distribution (Sjøvaag and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024), promoting questions as to the jurisdiction of states to ensure these critical infrastructures benefit citizens (Pickard Citation2020). Journalism’s material infrastructures thus make up the ecosystem within which news is circulated and received, conditioned by the infrastructure actors that shape the organisation of journalistic production.

The critical nature of communication infrastructures creates dependencies (Plantin et al. Citation2018). Because every part of society relies on these services (Nechushtai Citation2018), infrastructures have power – the power to set the conditions under which others operate (Winseck Citation2017), to implement actions across territories (Mann Citation2008) – resulting in technological enclosure (Sadowski Citation2020). When hardware and software are widely shared, it also creates path dependent continuities in norms and practices (Simon Citation2022) through computational and organisational integration (Helmond, Nieborg, and van der Vlist Citation2019). Dependencies can occur at all levels of journalism’s infrastructure: At the physical level of networked hardware such as cables, routers, and data centres; at the level of data transmission where standards and protocols dictate how data is stored and transported, and at the application layer where platforms operate (Hesmondhalgh et al. Citation2023). While data sovereignty “can apply to a range of agents across the spectrum from individual consumers to entire societies and countries” (Hummel et al. Citation2021, p.15), journalism’s data sovereignty concerns the ability to control the infrastructure where data is located, influence its development, and shape its dynamics (e.g., Floridi Citation2020). Moreover, beyond the question of where infrastructure power resides, data sovereignty also is also a question of “how such power is exercised” (Rone Citation2023, p. 1).

A key aspect of infrastructural dependence thus concerns their lack of regulation, as it can exclude people from universal service (Plantin et al. Citation2018), can abuse market power (Hintz, Dencik, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2017), and is difficult to oversee through the usual means of accountability (Rahman Citation2017). Moreover, because automatic systems of optimisation constantly shift data around the globe to balance the load of various infrastructure services, it is not always possible to pinpoint the exact location of data. Data infrastructures thus not only involve jurisdictional questions (Constantinides, Henfridsson, and Parker Citation2018), sovereignty issues also arise because surveillance laws often kick in once data cross borders, threatening news organisations’ ability to protect their own data, and ultimately, their sources (Liu and Wang Citation2022). The infrastructure dependencies that journalism face thus include data – being able to store, process, access and protect information; distribution – being able to transmit content to reach audiences; and regulatory jurisdiction – the extent to which authorities are able to place regulatory demands on these essential services.

As Plantin et al. (Citation2018) have argued, platforms are starting to operate as infrastructures in their own right – becoming critical infrastructures that societies rely on for work, commerce, and daily life. Beyond this level of platform infrastructurisation, the digital backbone is also host to a range of other players, including governments, energy companies, primary industries, telecoms, technology companies and investment firms. The private actors operating in these realms own subsea fibre cables, internet exchange points and data centres, as well as broadband and mobile infrastructure at the access level. The network of actors involved in the ownership of these backbones suggests that the notion of dependency (Plantin and Punathambekar Citation2019) or capture (Nechushtai Citation2018) is not taken far enough in considering how power is distributed in journalism’s ecosystem.

Materials and Methods

Our infrastructure mapping is based on the methodology developed by Flensburg and Lai (Citation2020) to focus on actors and data streams involved in the digital communication infrastructure. As our interest is in physical backbone structures and their data practices and jurisdictions, our mapping concerns ownership of subsea fibre cables, internet exchange points (IXPs), content delivery networks (CDNs), cloud providers, and data centres; their position in journalism’s ecosystem for news production and distribution; and their regulation. The motivation for mapping these infrastructures is to highlight the range of actors that should be considered within the parameters of infrastructure power and control over essential data services that influence journalism’s autonomy.

Our primary method is document analysis – a procedure that includes finding, selecting, appraising, and synthesising data found in documents (Bowen Citation2009). We mobilised three types of document searches to obtain data. First, we searched the government databases for relevant regulatory reports, white papers, and legal documents to map key sectoral players, the responsible agencies and oversight bodies involved, and relevant policies. Incidentally, the only regulation pertaining to all sectors of the backbone infrastructure is general competition law. Providers of open internet traffic are, furthermore, subject to the Electronic Communications Act (E-com Act, 2022), which stipulates universality of service, fair competition, and security regulations.

This document search revealed not only a lack of official policy; it also showed that infrastructural oversight is spread across a range of ministries – from the Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development (responsible for the national data centre strategy), to the Ministry of Transport (to which the Norwegian Communications Authority reports) and the Ministry of Justice and Public Security (responsible for the safety of critical infrastructures). We searched the databases of these Ministries as well as the databases of the Norwegian Digitalisation Agency and the Ministry of Culture and Equality (responsible for the media sector) revealing that only the national data centre strategy contained any mapping of actors (KDD. Citation2021), while the Norwegian Communications Authority also keeps track of key actors in the backbone structure (e.g., Nkom Citation2023).

Second, we performed a general web search to map actors in the CDN, IXP, data centre and cloud sectors not tracked by government reports. We established a basic Excel spreadsheet to systematise the data. Third, we used database search (regnskapstall.no) to source ownership control over each company listed in the database. Foreign ownership was ascertained through financial news sites and stock trading sites. Finally, we surveyed the industry trade press to track ownership and policy developments since 2020. We then used the database to analyse the ecosystem of backbone technology players relevant to the news industries, including ownership (foreign or domestic and private or public ownership), and legal jurisdiction. Cloud services were traced by surveying the data protection policies of major media companies in NorwayFootnote1. As not all publishers’ official data protection policies were transparent about the cloud services used, we contacted their data protection officers directly via email (13 in total). Only 5 companies responded to our inquiries, but these corporations together control 65% of the newspapers in Norway (encompassing 148 outlets). Among respondents is also the public service broadcaster NRK, reaching 91% of the population daily (NRK. Citation2022)Footnote2.

There are inherent limitations to these data collection procedures, the most significant of which is the rapidly shifting ecology under investigation. However, the overall structures captured by this mapping highlight important dependencies that are likely to persist even if the composition of service providers change. Public information about certain sectors is also relatively patchy (e.g., the data centre and cloud services sectors), not least because service definitions tend to vary (e.g., a data centre can range from large hyperscale warehouses to a few servers in a basement). Substantial cross-referencing of various lists of providers was thus necessary to substantiate the database. The fact that most media companies contacted about their cloud providers did not respond to our inquiries also limits the extent to which we can draw exhaustive conclusions about Norwegian media’s use of cloud providers. We were, however, able to establish the cloud infrastructures used by most journalistic organisations, who were all using a combination of the main leaders in the cloud market. We also left satellite transmission out of our investigation. Satellite transmission has been an important infrastructure for broadcasting and cable TV delivery (see Youmans and Powers Citation2012), but despite the growth of low-orbit systems such as Elon Musk’s Starlink, satellites are, as of yet, marginal as internet infrastructure (Graydon and Parks Citation2020).

Analysis

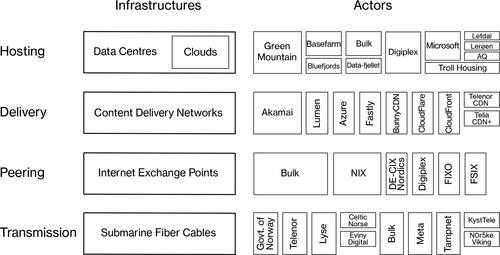

In the following, we outline the technologies involved in the backbone infrastructure of the internet and how they create interdependencies in the data management, news distribution, and jurisdiction for the journalism industries in Norway. Overall, the ecosystem encompasses 12 submarine fibre cables, 11 internet exchange points, nine content delivery network providers, 30 data centres, and three main cloud services. These constitute the actors in the ecosystem on which news organisations rely.

Subsea cables

Submarine fibre cables carry 99% of internet traffic around the world (Munn Citation2023), linking users with content worldwide (see Starosielski Citation2015). Subsea cables are essential for information sharing and access across continents, manifested at its most basic level with the hyperlink, which journalists use in digital publishing on a daily basis, the primary function of which is to be transparent about sources and pointing users to further information (Sjøvaag et al. Citation2019). There is growing investment in submarine infrastructure across the globe, particularly by Meta and Google (Ball Citation2021). This leads to stronger interdependencies between the subsea sector and the data centre sector as fibre operators seek to stretch their cables directly into data centres for decreased latency (Hillman Citation2021) and enhanced security.

Two of 12 submarine cables that connect Norway to the global internet are directly controlled by the Government of Norway through their ownership of Space Norway (the Svalbard Undersea Cable connecting the mainland to the arctic islands of Svalbard), and Statnett who owns and operates the national electric grid (Skagerrak 4 connecting Norway with Denmark). The telecom Telenor (majority owned by the Government of Norway at 53,96%) owns the Bodo-Rost Cable (connecting the mainland to the coastal islands of Lofoten) and operates the Svalbard Undersea Cable. Public ownership is secured through a further four networks, through municipality owned energy companies controlling the Celtic Norse Cable connecting Norway to Ireland (NTE Market, Eidsiva Energi and TrønderEnergi own 1/3 each); the UK-NO Cable connecting Norway and the UK, and Skagenfiber West linking Norway with Denmark (both owned by the energy company Lyse); and the Eviny Digital Cable that runs down the coast connecting the cities of Bergen and Stavanger (owned by the state-controlled energy company Statkraft and six municipalities). Private ownership includes the Havfrue Cable connecting Norway with the US (owned by Bulk, Aqua Comms, Google and Meta); Havsil linking Norway and Denmark (owned by the technology company Bulk); N0r5ke Viking which runs along the coast of Norway (owned by N0r5ke Fibre); the Polar Circle Cable which links the northern coast (owned by KystTele); and the Tampnet Offshore FOC Network which connects Norway with the UK (owned 50/50 by the investment firm 3i Infrastructure and the Danish pension fund APC). Of all these ownerships, only two are based outside of Norway, the Tampnet and Havfrue cables. These cables are essential for news organisations to reach national audiences along the expansive coastline of a geographically dispersed country such as Norway.

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs)

Content delivery networks, responsible for over 70% of internet traffic worldwide (Ghaznavi et al. Citation2021), are networks of servers that act as caches to speed up delivery of content close to the end user, most of which is video content (Li et al. Citation2021). News media rely on these services to stream live coverage and to run dynamic websites with interactive features. Most media companies use a general purpose CDN such as Akamai, Lumen or Cloudflare, but major platforms tend to run on their own internal CDNs. Amazon, Netflix, Apple, YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok all run on their own CDNs (Sowell Citation2020). Due to their size and resources these global actors command considerable power over this component of the digital infrastructure compared to Norwegian news providers. Media companies need CDNs partly because peak traffic is too demanding for their own origin servers to deliver quality content to users, and partly because outsourcing content delivery is cheaper than building in-house capacity (Sjøvaag, Olsen, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024). For instance, traffic to the BBC website during the 2020 US election peaked around 41.000 requests per second – traffic that is too high for BBC’s servers to handle on their own (Ishmael Citation2021). BBC has used Akamai and Limelight to traffic content to users internationally and has its own CDN, BBC Internet Distribution Infrastructure (BIDI), delivering directly to users in the UK (Benedetto Citation2016). This market is growing increasingly concentrated (e.g., Winseck Citation2017), the top providers being Amazon Web Services (AWS), Akamai, Google, Fastly and Edgio. As most CDNs are located in data centres, their operations are also interdependent.

There are nine CDN providers offering services in the Norwegian media marketplace. All but one (Telenor CDN) are foreign owned, six of which are listed on the US stock exchange: Akamai, Microsoft’s Azure, Amazon’s Cloudfront, CloudFlare, Fastly and Lumen. One CDN, BunnyCDN is privately owned by Dejan Pelzel and registered in Slovenia. The Swedish/Finnish owned telecom Telia provides local CDN connector services. Among the providers, Telenor CDN and Telia CDN + are the only CDNs with any public ownership attached. Akamai is the primary provider of CDN services to Norwegian public service broadcasters (Sjøvaag, Olsen, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024). Reliance on a single CDN can entail a risk. When Fastly experienced a configuration problem in 2021, all of its client websites went down, including Bloomberg, the New York Times, the Norwegian media company Schibsted’s newspapers, as well as sites on the gov.uk domain, demonstrating the dependency of news media on CDN services (The Guardian Citation2021). Furthermore, Norwegian broadcasters use cloud services such as Google Cloud for back catalogue storage, illustrating the interdependencies between the storage and delivery sectors in the communication backbone infrastructure.

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs)

Internet Exchange Points (IXPs) are important in the ecosystem because they route traffic between operators. IXPs are peering facilities where autonomous systems can connect with multiple peers at once through switches. The University of Oslo (public and government owned and funded) owns and operates the IXP backbone in Norway, Norway Internet Exchange (distributed across six IXPs housed by the University of Oslo and four other universities), while a further five IXPs are privately owned, two of which are based in Norway (Blix Group and Bulk) and three are owned by actors based in Germany (Deutche Commercial Internet Exchange), Luxemburg (Infrastructure Norway) and the US (Terrahost). Most internet traffic in Norway is peered through private IXP infrastructure (Nkom Citation2023), Bulk being the main provider. As IXPs are key in networking traffic, they provide interdependencies between content providers like news media and internet service providers, linking content across the backbone and access level of the internet, and exchanging traffic between internet service providers (ISPs) and CDNs.

Cloud Services

Cloud infrastructures are centralised, networked, and widely distributed services (Furlong Citation2021) that host data. Cloud services are not only crucial for content storage and backup; they are also key for configuration of on-demand usage of computer resources (Narayan Citation2022). Publishers use cloud services for various functions within their commercial and editorial operations. These services include storing and processing customer and content data, which serve essential roles in news content production and customer management (e.g., analytics, back catalogue filing, personalisation of content and programmatic advertising). For example, the BBC outsources authentication processes through Google Cloud and website rendering through Amazon Web Services (AWS) (Clark Citation2020). This combination of providers is seen also in the Norwegian context. Among the companies that disclosed their cloud service provides, most rely on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP), while a few combine Google Cloud with either AWS or Microsoft’s Azure. Cloud services are also important for content flow between networks (Arsenault Citation2017), enabled by the data transfer and processing ability of major actors. Media companies are therefore becoming increasingly reliant on cloud services (Simon Citation2022) for data management and processing. As cloud reliance not only pertains to content but extends to user data, this has an impact on data privacy (Monzer et al. Citation2020). Cloud providers are interdependent with data centres as they tend to host cloud services.

Data Centres

Data centres are physical structures that provide networking, computing, and storage (Munn Citation2023). Most data centres in Norway are colocation facilities that rent out server space, rather than hyperscale data centres that can facilitate heavy processes such as crypto-mining. The data centre sector in Norway is dominated in its totality by private actors. Among the 30 established data centres in Norway, 18 are owned by foreign-based companies, either stock listed (such as Microsoft) or owned by investment firms (e.g., Azreli Group who owns the dominant actor Green Mountain and their six data centres). Domestic ownership is spread among private individuals and families who are also invested in the primary industries (e.g., mining and fishing). Data centres typically hold both cloud and CDN services that host and stream traffic, and the IXPs that route traffic. Increasingly, data centres are also landing sites for subsea internet cables, creating interdependencies along the entire backbone infrastructure. For the news industries, this adds another layer of dependency on external structures that holds the power to make or break their connection with audience and advertising markets as well as the dataflows that power news production.

The overall infrastructure is mapped out in .

In summary, the backbone infrastructure consists of technologies and actors that shape the data sovereignty, distribution control, and jurisdiction of the media industries in Norway. Media distribution is thus dependent on a technology dominated by a handful of foreign-owned, stock-listed providers of content delivery services, whose infrastructures in turn rely on the internet access provided by internet service providers (licenced telecoms) whose peering is provided primarily through private internet exchange points (IXPs). As the news media outsource their data management to cloud services, provided predominantly by Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure, and Amazon Web Services, journalism is dependent on a concentrated industry of storage and streaming providers, who are in turn reliant on an increasingly foreign-owned data centre sector, whose algorithms move data around global networks, challenging journalism’s data sovereignty. The jurisdiction that authorities have over most of these infrastructures is restricted to general competition law, and thus devoid of regulation beyond those pertaining to net neutrality and GDPR. Moreover, whereas television distribution is secured through must-carry obligations for digital terrestrial transmission and through the cable system, CDNs and cloud services have no such obligations. This has implications for the reach of public service broadcasting, particularly during times of crisis, challenging their societal preparedness obligations. The infrastructures on which the media rely thus lie outside the reach of the governance system established to ensure universal communication services. Hence, while journalism is considered an important element in this democratic infrastructure, the backbone infrastructures that news media need to actually reach audiences, feature in regulation as well as in industry perceptions (see Sjøvaag, Olsen, and Ferrer-Conill Citation2024) as ‘just technology’. Whereas regulators have been eager to check the power of actors that dominate the platform landscape (e.g., COM Citation2020); consideration for the dependencies created by the backbone layer seems to fly under the radar of both media regulators and news industry stakeholders.

The backbone infrastructure of the media ecosystem in Norway not only creates dependencies in the distribution and data sovereignty of media companies; its sectors are also interdependent to such an extent that the dominance of foreign, private actors assumes more and more power over the infrastructure. While public ownership is present in the transmission and peering sectors, controlling around half of each of these infrastructures, the private hosting, peering and delivery services on which journalism depends for data management and distribution are out of reach of regulation. The extent to which the media ecosystem is able to provide universal communication services thus rests primarily on the ability of competition law to oversee the operations of highly varied backbone actors whose interests and actions are interdependent of each other.

Discussion

Journalism relies on the backbone communication infrastructure for distribution through the transmission layer (subsea cables delivering content from foreign-based providers, or transmitting data along the coast); peering at IXPs connecting content providers (e.g., government services, online library services, and other media); CDN services for delivering streaming and dynamic web content; and cloud services housed at data centres for data storage and processing. This communication infrastructure operates in both directions. First, news organisations need cloud services and CDNs for news production and dissemination, and then they rely on IXPs and subsea cables for the public to access relevant information. Hence, journalism is dependent on every layer of the infrastructure for content distribution and data processing. This dependency has so far been overlooked in digital journalism research – even here considered primarily as “just technology”, when in fact they perform core functions needed for a well-functioning democratic infrastructure in which news media play an essential role.

Together, the backbone infrastructures that enable data packet flow and the data centres and clouds that provide storage and processing (Huang and Mayer Citation2022), influence journalism organisations in two ways. They inform make-or-buy decisions (Constantinides, Henfridsson, and Parker Citation2018; Narayan Citation2022) about technology acquisitions that influence the level of control that media companies have over their data; and they influence the level of distribution control that media have over their products. The backbone infrastructure thus constitutes the material condition for media distribution and data management. Beyond these material dependencies, the ecosystem consists of a network of actors that operate across sectors. Their ownership interests collectively set the conditions for the media industries. As the sectors are interdependent, developments in one sector affects another, influencing how stakeholders act. CDNs are moving into the cloud market to utilise off-peak capacity (e.g., Akamai Citation2023), and platform operators (e.g., Meta, Google) are building data centres and subsea fibre cables to increase their control over traffic flow (Ball Citation2021). Furthermore, the range of actors involved in the ecosystem (telecoms, energy companies, investment firms, primary industries, technology companies), suggests that the financial relationships that condition how digital journalism evolves and survives, create networked dependencies where foreign, privately owned operators assume greater control over the infrastructure.

The interdependencies of this ecosystem amount to 1) the infrastructurisation of ownership across the layers that condition power relations within the infrastructure, and 2) the increasing overlap between business interests and technological dependencies spanning multiple sectors. To the first point, platforms are becoming infrastructures in their own right (Plantin et al. Citation2018), seen in how companies like Meta, Google and Amazon venture into subsea cable consortia, in how they establish cloud services and content delivery networks, and the rate at which they build data centres. Moreover, foreign tech giants are assuming control over larger and larger sections of the transmission, peering, delivery and hosting services on which journalism relies. As for the second point, the sectors that make up the internet infrastructure are becoming increasingly intertwined and co-dependent, whereby the transmission and hosting services in particular are concentrating in power. More and more of the data reliant on this infrastructure travel through closed networks out of the reach of national regulatory jurisdictions, to which issues of transparency, security, privacy, and fair competition remain unresolved. Together, the interdependencies of the digital infrastructures that support journalism point towards a concentration of power beyond the platforms and further away from journalistic actors. This suggests that as news organisations become more reliant on these third-party infrastructures, their autonomy and sovereignty are diminished.

The sociotechnical perspective brings to digital journalism studies a material conceptualisation of what dependencies mean in the context of journalism’s relationship with the platforms (Nechushtai Citation2018; Simon Citation2022). Not only do the data protocols, data compatibility requirements, and governance rules (Bowker and Star Citation2000; Constantinides, Henfridsson, and Parker Citation2018) that administer CDN distribution and cloud storage condition data and distribution practices in journalism organisations; the power of these increasingly interdependent internet stakeholders (Winner Citation1980) also restrict and enable autonomy (Huang and Mayer Citation2022), as they set the conditions under which others operate (Winseck Citation2017). Akamai, Amazon, and Google thus become so big that their power, reaching across the platform layer and into the backbone infrastructure, threatens technological enclosure (Sadowski Citation2020). The market dominance of these actors is also growing so extensive that their actions seem beyond the reach of regulatory reaction. Meta has not only threatened to withdraw Facebook from Europe and Canada (Meta Citation2023; The Guardian Citation2020), they have worked to stall or oppose legal procedures, seen for instance in their countersuit against the Norwegian Data Protection Authority’s ruling against Meta’s use of personal data for personalised advertising (Datatilsynet Citation2023). Alphabet has also actively opposed Bill 2630, known as the Fake News Law in Brazil (Vilasboas Citation2023). These actions mobilise power at the platform level. Who is to say they will not do the same in the cable and cloud sectors. The dependencies that journalism faces as they grow more reliant on these infrastructures thus effectively amount to the ‘threat of exit’ that these actors can mount if at all faced with what they perceive as unfavourable regulatory conditions, to which neither the media nor the state seem to have much recourse for action. Hence, as the material power of these infrastructure actors can be translated into political and social power (McChesney Citation2013), concentration in these markets increases the threat of abuse of such power (Pickard Citation2013). These risks constitute an understudied area, beyond the scope of this study, that call for further research.

What this study uncovers is how the backbone infrastructure of communication shapes the material conditions of digital journalism beyond the platform level, introducing interdependencies in the data, distribution and jurisdiction that condition the autonomy of journalism institutions to operate independently and autonomously. As the sociotechnical perspective highlights, technology is not just technology, but shapes the culture and practice of journalism (Lewis and Westlund Citation2015; Lischka, Schaetz, and Oltersdorf Citation2023). The contribution of this study is thus to increase sensitivity to the issues of infrastructure interdependencies, as it raises the question of what happens if these dominant players retract from the market, exclude certain actors from services, or abuse their market power (Hintz, Dencik, and Wahl-Jorgensen Citation2017; Plantin et al. Citation2018; Rahman Citation2017).

Conclusion

The role of the internet backbone in shaping distribution suggests that the notion of capture extends well beyond the platforms. Platforms like Meta, Google and Microsoft may be becoming infrastructures in their own right, but this infrastructurisation of platform power is enabled first and foremost by their material control over the backbone structures that transmit, peer, deliver, and store the data upon which journalism relies. As this analysis shows, the backbone of the internet in Norway is owned and operated by a host of actors, many of which are foreign owned and commercially motivated. The majority of these sectors have low levels of public oversight and minimal or no regulation. Moreover, their functions are becoming increasingly intertwined, creating interdependencies along the backbone infrastructure that creates new levels of capture for the news industries. While this study focuses on the Norwegian context, the global presence of the actors and the nature of the technologies suggest that our findings could reflect multiple national journalistic contexts. Major platforms like Google, Meta and Amazon are key in creating these interdependencies, as their interests extend sectoral boundaries, acting as key resources in data management and distribution for the media industries. The presence of few-to-no alternatives aside from these players thus puts a strain on journalism’s data sovereignty and distribution autonomy, to which there are few regulatory options to ensure the fairness and transparency of these infrastructural players.

Our findings uncover how deep journalism’s third-party reliance reaches into the internet backbone. This has implications for journalism’s ability to operate and reach audiences. As the state does not regulate these essential services to ensure universal service, news organisations cannot mount distribution demands on the technologies that stream content or process their data. Must-carry requirements have historically regulated distribution technologies to ensure the infrastructure for the information freedom and public debate that democracy relies on, and that journalism ideally ensures. Public alternatives may provide a solution to ensure both data sovereignty and distribution access for the news industries, but as debates about the appropriateness of a ‘public cloud’ continue – if states will not own such public goods, they should at least regulate them. News industries should thus increase their conscientiousness in technology acquisitions, as well as heighten their attention to the location of their data. As a profession that questions power, journalists should also build their awareness of the democratic implications of whole societies becoming reliant on these unregulated, commercially driven data infrastructures that are largely controlled by multinational technology companies.

Limitations and Further Research

Like all studies this one comes with limitations, the most important one being that a mapping of this kind can only provide a snapshot of developments. Ownership data concerning these sectors is, moreover, relatively tricky to trace. The interdependencies we try to uncover thus reflect the shifting nature of these backbone industries. We also only cover one national territory, while many of these technologies span national borders. It would be useful for future research to investigate where exactly the data that these global networks host are located, what regulations and jurisdictions govern them, and what this means for information security for journalism organisations. Further research is also needed to substantiate the reach of these actors beyond national borders. While infrastructure regulation is a national concern, these networks are global. Comparative research would thus help to establish more substantially the extent of interdependencies along the backbone layers, including the role of emerging low-orbit satellite systems, and what edge computing may bring to debates about journalism’s data sovereignty. Finally, we encourage further research into the ways in which infrastructure actors may exercise their power.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The following companies were contacted: The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), TV 2, Amedia, Schibsted, Polaris, Mentor Medier, DN Media Group, AllerMedia AS, Trønder-Avisa, Egmont, Viaplay Group, Warner Bros Discovery, and Modern Times Group (MTG).

2 The following companies responded: The Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK), Amedia, Schibsted, Polaris, MentorMedier.

References

- Akamai. 2023. “Akamai’s Differentiated Cloud Strategy.” Akamai. February 21. https://www.akamai.com/blog/cloud/akamai-differentiated-cloud-strategy.

- Ananny, M. 2018. Networked Press Freedom: Creating Infrastructures for a Public Right to Hear. Cambridge, MA: MIT press.

- Arsenault, A. H. 2017. “The Datafication of Media: Big Data and the Media Industries.” International Journal of Media & Cultural Politics 13 (1): 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1386/macp.13.1-2.7_1

- Ball, J. 2021. “Facebook and Google’s New Plan? Own the Internet.” Wired. October 7. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/facebook-google-subsea-cables.

- Benedetto, F. 2016. “BIDI: The BBC Internet Distribution Infrastructure explained.” BBC. September 22. https://www.bbc.co.uk/blogs/internet/entries/8c6c2414-df7a-4ad7-bd2e-dbe481da3633

- BEREC. 2022. “Draft BEREC Report on the Internet Ecosystem.” Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications.

- Bowen, G. A. 2009. “Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method.” Qualitative Research Journal 9 (2): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Bowker, G. C., and S. L. Star. 2000. “Invisible Mediators of Action: Classification and the Ubiquity of Standards.” Mind, Culture, and Activity 7 (1-2): 147–163. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327884MCA0701&2_09

- Camaj, L., J. Martin, and G. Lanosga. 2022. “The Impact of Public Transparency Infrastructure on Data Journalism: A Comparative Analysis between Information-Rich and Information-Poor Countries.” Digital Journalism. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2077786

- Carlson, M. 2020. “Journalistic Epistemology and Digital News Circulation: Infrastructure, Circulation Practices, and Epistemic Contests.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 230–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856921

- Chiumbu, S., and A. Munoriyarwa. 2023. “Exploring Data Journalism Practices in Africa: Data Politics, Media Ecosystems and Newsroom Infrastructures.” Media, Culture & Society 45 (4): 841–858. https://doi.org/10.1177/01634437231155341

- Chua, S. 2023. “Platform Configuration and Digital Materiality: How News Publishers Innovate Their Practices Amid Entanglements with the Evolving Technological Infrastructure of Platforms.” Journalism Studies 24 (15): 1857–1876. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461670X.2023.2247494

- Chua, S., and O. Westlund. 2022. “Platform Configuration: A Longitudinal Study and Conceptualization of a Legacy News Publisher’s Platform-Related Innovation Practices.” Online Media and Global Communication 1 (1): 60–89. https://doi.org/10.1515/omgc-2022-0003

- Clark, M. 2020. “Moving BBC Online to the Cloud.” BBC, October 29. https://medium.com/bbc-product-technology/moving-bbc-online-to-the-cloud-afdfb7c072ff

- COM. 2020. “Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market for Digital Services.” (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC.

- Constantinides, P., O. Henfridsson, and G. G. Parker. 2018. “Introduction—Platforms and Infrastructures in the Digital Age.” Information Systems Research 29 (2): 381–400. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.2018.0794

- Datatilsynet. 2023. “The Norwegian Data Protection Authority’s Decision against Meta is Extended to the EU/EEA and Made Permanent.” Datatilsynet. https://www.datatilsynet.no/en/news/aktuelle-nyheter-2023/the-norwegian-data-protection-authoritys-decision-against-meta-is-extended-to-the-eueea-and-made-permanent/

- Diakopoulos, N. 2020. “Computational News Discovery: Towards Design Considerations for Editorial Orientation Algorithms in Journalism.” Digital Journalism 8 (7): 945–967. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1736946

- E-com Act. 2022. “E-com Act [LOV-2003-07-04-83] Act Relating to Electronic Communications (The Electronic Communications Act).” https://lovdata.no/dokument/NLE/lov/2003-07-04-83

- Edwards, P. N., G. C. Bowker, S. J. Jackson, and R. Williams, University of Michigan. 2009. “Introduction: An Agenda for Infrastructure Studies.” Journal of the Association for Information Systems 10 (5): 364–374. https://doi.org/10.17705/1jais.00200

- Eldridge, S. A., K. Hess, E. C. Tandoc, and O. Westlund. 2021. “Navigating the Scholarly Terrain: Introducing the Digital Journalism Studies Compass.” In Definitions of Digital Journalism (Studies), edited by S. EldridgeII, K. Hess, E. TandocJr., O. Westlund, 73–90. Routledge.

- Fischli, R. 2022. “Data-Owning Democracy: Citizen Empowerment through Data Ownership.” European Journal of Political Theory 23 (2): 204–223. https://doi.org/10.1177/14748851221110316

- Flensburg, S., and S. S. Lai. 2020. “Mapping Digital Communication Systems: Infrastructures, Markets, and Policies as Regulatory Forces.” Media, Culture & Society 42 (5): 692–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719876533

- Floridi, L. 2020. “The Fight for Digital Sovereignty: What It is, and Why It Matters, Especially for the EU.” Philosophy & Technology 33 (3): 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-020-00423-6

- Frischmann, B. M. 2012. Infrastructure: The Social Value of Shared Resources. Oxford University Press.

- Furlong, K. 2021. “Geographies of Infrastructure II: Concrete, Cloud and Layered (in) Visibilities.” Progress in Human Geography 45 (1): 190–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132520923098

- Ghaznavi, Milad, Elaheh Jalalpour, Mohammad A. Salahuddin, Raouf Boutaba, Daniel Migault, and Stere Preda. 2021. “Content Delivery Network Security: A Survey.” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 23 (4): 2166–2190. https://doi.org/10.1109/COMST.2021.3093492

- Graves, L., and C. W. Anderson. 2020. “Discipline and Promote: Building Infrastructure and Managing Algorithms in a “Structured Journalism” Project by Professional Fact-Checking Groups.” New Media & Society 22 (2): 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819856916

- Graydon, M., and L. Parks. 2020. “Connecting the Unconnected’: A Critical Assessment of US Satellite Internet Services.” Media, Culture & Society 42 (2): 260–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719861835

- Gutierrez Lopez, M., C. Porlezza, G. Cooper, S. Makri, A. MacFarlane, and S. Missaoui. 2023. “A Question of Design: Strategies for Embedding AI-Driven Tools into Journalistic Work Routines.” Digital Journalism 11 (3): 484–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2043759

- Hase, V., K. Boczek, and M. Scharkow. 2023. “Adapting to Affordances and Audiences? A Cross-Platform, Multi-Modal Analysis of the Platformization of News on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter.” Digital Journalism 11 (8): 1499–1520. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2128389

- Helberger, N. 2020. “The Political Power of Platforms: How Current Attempts to Regulate Misinformation Amplify Opinion Power.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 842–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773888

- Hesmondhalgh, D. 2022. “The Infrastructural Turn in Media and Internet Research.” In The Routledge Companion to Media Industries, edited by P. McDonald, 132–142. Routledge.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., and A. Lotz. 2020. “Video Screen Interfaces as New Sites of Media Circulation Power.” International Journal of Communication 14: 386–409.

- Hesmondhalgh, D., R. C. Valverde, D. B. V. Kaye, and Z. Li. 2023. “Digital Platforms and Infrastructure in the Realm of Culture.” Media and Communication 11 (2): 296–306. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6422

- Helmond, A., D. B. Nieborg, and F. N. van der Vlist. 2019. “Facebook’s Evolution: Development of a Platform-as-Infrastructure.” Internet Histories 3 (2): 123–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/24701475.2019.1593667

- Hillman, J. 2021. “Securing the Subsea Network: A Primer for Policymakers.” Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/resrep30032.4.pdf.

- Hintz, A., L. Dencik, and K. Wahl-Jorgensen. 2017. “Digital Citizenship and Surveillance Society: Introduction.” International Journal of Communication 11 (2017): 731–739.

- Huang, Y., and M. Mayer. 2022. “Power in the Age of Datafication: Exploring China’s Global Data Power.” Journal of Chinese Political Science 28 (1): 25–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-022-09816-0

- Hummel, P., M. Braun, M. Tretter, and P. Dabrock. 2021. “Data Sovereignty: A Review.” Big Data & Society 8 (1): 205395172098201. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720982012

- Ishmael, J. 2021. “Delivering BBC Online Using Serverless.” BBC Product and Technology, January 20. https://medium.com/bbc-product-technology/delivering-bbc-online-using-serverless-79d4a9b0da16.

- Ivancsics, Bernat, Eve Washington, Helen Yang, Emily Sidnam-Mauch, Ayana Monroe, Errol Francis, II, Joseph Bonneau, Kelly Caine, and Susan E. McGregor. 2023. “The Invisible Infrastructures of Online Visibility: An Analysis of the Platform-Facing Markup Used by US-Based Digital News Organizations.” Digital Journalism 11 (8): 1432–1455. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2156365

- Just, N. 2022. “Which Is to Be Master? Competition Law or Regulation in Platform Markets.” International Journal of Communication (16): 504–524.

- KDD. 2021. Norske Datasenter – Berekraftige, Digitale Kraftsenter. [Norwegian data centres – Sustainable, digital power centres]. Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development.

- Kristensen, L. M., and J. M. Hartley. 2023. “The Infrastructure of News: Negotiating Infrastructural Capture and Autonomy in Data-Driven News Distribution.” Media and Communication 11 (2) https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6388

- Lewis, S. C., and O. Westlund. 2015. “Actors, Actants, Audiences, and Activities in Cross-Media News Work: A Matrix and a Research Agenda.” Digital Journalism 3 (1): 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2014.927986

- Li, X., M. Darwich, M. A. Salehi, and M. Bayoumi. 2021. A survey on cloud-based video streaming services. In Advances in Computers, 123, 193–244. Elsevier.

- Lischka, J. A., N. Schaetz, and A. L. Oltersdorf. 2023. “Editorial Technologists as Engineers of Journalism’s Future: Exploring the Professional Community of Computational Journalism.” Digital Journalism 11 (6): 1026–1044. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1995456

- Liu, J., and J. Wang. 2022. “Social Data Governance: From Reflective Practices to Comparative Synthesis.” Big Data & Society 9 (2): 205395172211397. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517221139786

- Mann, M. 2008. “Infrastructural Power Revisited.” Studies in Comparative International Development 43 (3-4): 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-008-9027-7

- McChesney, R. W. 2013. “Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet against Democracy.” The New Press.

- Meta. 2023. “Changes to News Availability on our Platforms in Canada.” Meta, June 1. https://about.fb.com/news/2023/06/changes-to-news-availability-on-our-platforms-in-canada/.

- Monzer, C., J. Moeller, N. Helberger, and S. Eskens. 2020. “User Perspectives on the News Personalisation Process: Agency, Trust and Utility as Building Blocks.” Digital Journalism 8 (9): 1142–1162. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1773291

- Moran, R. E., and E. Nechushtai. 2023. “Before Reception: Trust in the News as Infrastructure.” Journalism 24 (3): 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1177/14648849211048961

- Mosco, V. 2009. The Political Economy of Communication. 2nd ed. Sage.

- Munn, L. 2023. “Red Territory: Forging Infrastructural Power.” Territory, Politics, Governance 11 (1): 80–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2020.1805353

- Napoli, P. M., S. Stonbely, K. McCollough, and B. Renninger. 2017. “Local Journalism and the Information Needs of Local Communities: Toward a Scalable Assessment Approach.” Journalism Practice 11 (4): 373–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1146625

- Narayan, D. 2022. “Platform Capitalism and Cloud Infrastructure: Theorizing a Hyper-Scalable Computing Regime.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54 (5): 911–929. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221094028

- Nechushtai, E. 2018. “Could Digital Platforms Capture the Media through Infrastructure?” Journalism 19 (8): 1043–1058. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884917725163

- Nielsen, R. K., and S. A. Ganter. 2022. The Power of Platforms: Shaping Media and Society. Oxford University Press.

- Nkom. 2023. “Internett i Norge: Årsrapport 2023 [Internet in Norway: Annual Report 2023].” The Norwegian Communications Authority. file:///Users/2917924/Downloads/Internet%20in%20Norway%20-%20Annual%20Report%202023.pdf

- NRK. 2022. “NRK i verden: Årsrapport og årsregnskap 2022.” ["NRK in the World: Annual Report 2022”]. https://info.nrk.no/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/nrk_arsrapport_22.pdf.

- Olsen, R. K., B. Kalsnes, and J. Barland. 2021. “Do Small Streams Make a Big River? Detailing the Diversification of Revenue Streams in Newspapers’ Transition to Digital Journalism Businesses.” Digital Journalism 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1973905

- Partin, W. C. 2020. “Bit by (Twitch) Bit: “Platform Capture” and the Evolution of Digital Platforms.” Social Media + Society 6 (3)

- Peters, J. D. 2015. “Infrastructuralism: Media as Traffic between Nature and Culture.” In Traffic: Media as Infrastructures and Cultural Practices, edited by M. Näser-Lather, C. Neubert, 31–49. Brill.

- Pickard, V. 2013. “Social Democracy or Corporate Libertarianism? Conflicting Media Policy Narratives in the Wake of Market Failure.” Communication Theory 23 (4): 336–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/comt.12021

- Pickard, V. 2020. “Restructuring Democratic Infrastructures: A Policy Approach to the Journalism Crisis.” Digital Journalism 8 (6): 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1733433

- Pickard, V. 2022. “Can Journalism Survive in the Age of Platform Monopolies? Confronting Facebook’s Negative Externalities.” In Digital Platform Regulation: Global Perspectives on Internet Governance, T. Flew, F. R. Martin, 23–41. Springer Nature.

- Plantin, J. C., C. Lagoze, P. N. Edwards, and C. Sandvig. 2018. “Infrastructure Studies Meet Platform Studies in the Age of Google and Facebook.” New Media & Society 20 (1): 293–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444816661553

- Plantin, J. C., and A. Punathambekar. 2019. “Digital Media Infrastructures: Pipes, Platforms, and Politics.” Media, Culture & Society 41 (2): 163–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818376

- Rahman, K. S. 2017. “The New Utilities: Private Power, Social Infrastructure, and the Revival of the Public Utility Concept.” Cardozo L. Rev 39: 1621.

- Ratner, Y., S. Dvir Gvirsman, and A. Ben-David. 2023. “Saving Journalism from Facebook’s Death Grip”? The Implications of Content-Recommendation Platforms on Publishers and Their Audiences.” Digital Journalism 11 (8): 1410–1431. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2180403

- Rone, J. 2023. “The Shape of the Cloud: Contesting Data Centre Construction in North Holland.” New Media & Society.Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221145928

- Sadowski, J. 2020. “The Internet of Landlords: Digital Platforms and New Mechanisms of Rentier Capitalism.” Antipode 52 (2): 562–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12595

- Schjøtt Hansen, A., and J. M. Hartley. 2023. “Designing What’s News: An Ethnography of a Personalization Algorithm and the Data-Driven (Re) Assembling of the News.” Digital Journalism 11 (6): 924–942. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2021.1988861

- Simon, F. M. 2022. “Uneasy Bedfellows: AI in the News, Platform Companies and the Issue of Journalistic Autonomy.” Digital Journalism 10 (10): 1832–1854. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2022.2063150

- Sjøvaag, H., and R. Ferrer-Conill. 2024. “Digital Communications Infrastructures and the Principle of Universality: Challenges for Nordic Media Welfare State Jurisdictions.” In The Future of the Nordic Media Model: A Digital Media Welfare State?, edited by P. Jakobsson, F. Stiernstedt. Nordicom.

- Sjøvaag, H., R. K. Olsen, and R. Ferrer-Conill. 2024. “Delivering Content: Modular Broadcasting Technology and the Role of Content Delivery Networks.” Telecommunications Policy 48 (4): 102738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2024.102738

- Sjøvaag, H., E. Stavelin, M. Karlsson, and A. Kammer. 2019. “The Hyperlinked Scandinavian News Ecology: The Unequal Terms Forged by the Structural Properties of Digitalisation.” Digital Journalism 7 (4): 507–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2018.1454335

- Sowell, J. H. 2020. “Evaluating Competition in the Internet’s Infrastructure: A View of GAFAM from the Internet Exchanges.” Journal of Cyber Policy 5 (1): 107–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/23738871.2020.1754443

- Starosielski, N. 2015. The Undersea Network. Duke University Press.

- The Guardian. 2020. “Facebook Says it May Quit Europe Over ban on Sharing Data with US.” The Guardian, September 22. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/sep/22/facebook-says-it-may-quit-europe-over-ban-on-sharing-data-with-us.

- The Guardian. 2021. “What Caused the Internet Outage that Brought Down Amazon, Reddit and Gov.uk?” The Guardian, June 8. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/jun/08/edge-cloud-error-tuesday-internet-outage-fastly-speed

- Thorson, K., M. Medeiros, K. Cotter, Y. Chen, K. Rodgers, A. Bae, and S. Baykaldi. 2020. “Platform Civics: Facebook in the Local Information Infrastructure.” Digital Journalism 8 (10): 1231–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2020.1842776

- Vilasboas, P. 2023. “Google Aims to Avoid ‘Perverse’ Regulation in Brazil, Says Executive.” Reuters, June 28. https://www.reuters.com/technology/google-aims-avoid-perverse-regulation-brazil-says-executive-2023-06-27/

- Wallace, J. 2018. “Modelling Contemporary Gatekeeping: The Rise of Individuals, Algorithms and Platforms in Digital News Dissemination.” Digital Journalism 6 (3): 274–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2017.1343648

- Wenzel, A. D., and L. Crittenden. 2023. “Collaborating in a Pandemic: Adapting Local News Infrastructure to Meet Information Needs.” Journalism Practice 17 (2): 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2021.1910986

- Winner, L. 1980. The Whale and the Reactor: A Search for Limits in an Age of High Technology. University of Chicago Press.

- Winseck, D. 2017. “The Geopolitical Economy of the Global Internet Infrastructure.” Journal of Information Policy 7: 228–267. https://doi.org/10.5325/jinfopoli.7.2017.0228

- Youmans, W. L., and S. Powers. 2012. “Remote Negotiations: International Broadcasting as Bargaining in the Information Age.” International Journal of Communication 6: 24.

- Zamith, R. 2023. “Open-Source Repositories as Trust-Building Journalism Infrastructure: Examining the Use of GitHub by News Outlets to Promote Transparency, Innovation, and Collaboration.” Digital Journalism 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/21670811.2023.2202873