Abstract

Here, we provide a case-report of an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) patient with cognitive deficits best defined as posterior cortical atrophy (PCA). This is an unusual finding as ALS forms a spectrum with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), whereas PCA is predominantly associated with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. We hypothesize on whether ALS with PCA might be an under recognized phenotype considering multiple imaging studies in ALS have also reported (asymptomatic) parietal atrophy.

Introduction

Cognitive and behavioral changes in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are now recognized to occur in up to 50% of ALS patients. The current consensus is that ALS and frontotemporal dementia (FTD) form the phenotypic extremes of the same syndrome, the MND-FTD continuum (Citation1).

Here, we report an ALS patient with unusual cognitive deficits, which would meet the diagnostic criteria for the posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) clinicoradiologic syndrome. PCA is a syndrome characterized by deficits in higher-order visual processing and features consistent with aspects of Gerstmann and Balint syndromes but with relatively preserved episodic memory in the early stages. The most common pathology underlying PCA is Alzheimer Disease (AD) and is therefore also considered an atypical form of AD (Citation2). Although rare alternative underlying pathologies such as corticobasal degeneration, Lewy body disease, and prion disease have been reported (Citation3). To our knowledge, this is the first report of PCA in ALS.

Materials and methods

For this case report, data from the patients electronical medical record was used. Consent was provided for the use of clinical data for research purposes.

Results

Case history

The patient was a 74-year-old woman who had developed progressive clumsiness of her left hand over the course of 18 months. Three months later she also noticed weakness in her legs, which was initially left sided but had become symmetrical. In the weeks prior to her visit, she also found that speaking had become more difficult. She had to speak very deliberately and slowly in order to pronounce words correctly. She also had pseudobulbar affect. Swallowing was normal. She did not have weight loss or signs of (nocturnal) hypoventilation. She had frequent cramps, but had not noticed fasciculations.

She had undergone curative treatment for breast cancer >10 years ago. Otherwise her medical history was unremarkable. She was not taking medication and had no relevant intoxications. The family history was positive for cancer, but not for neuromuscular, neurodegenerative or psychiatric disorders.

On neurological examination the patient was alert and oriented. Speech and language seemed intact. Cranial nerve examination was unremarkable. We did not observe atrophy or fasciculation in the tongue. We were able to elicit several pseudobulbar reflexes.

Fasciculations were seen in her arms and there was atrophy of the left dorsal interossei. Sensory examination was normal. She had weakness of the neck flexors (MRC 4+), deltoids bilaterally (MRC 4), left biceps (MRC 4) and left intrinsic hand muscles (MRC 4), proximal leg muscles and ankle dorsiflexion bilaterally (MRC 4).

There was left-sided hyperreflexia of the triceps and biceps jerk as well as trapezius and pectoral reflexes, superficial abdominal reflexes were absent, the knee jerk was pathologically elevated bilaterally, but more on the left. There was sustained ankle clonus and a left-sided Babinski. She could walk on her heels and toes. She had a positive Gower’s sign. The Romberg was negative and she could tandem walk.

Laboratory studies (including Borrelia, syphilis, and HIV serology) did not reveal any relevant abnormalities. We did not perform a lumbar puncture. Cervical and lumbar spine MRI scans showed age-related degeneration, but no compression of the cord or roots. Brain MRI (one year prior to presentation) showed some generalized atrophy (GCA 1) but was considered normal for her age. Needle-EMG showed extensive denervation and re-innervation in the lumbosacral region that fulfilled the revised El Escorial criteria. Re-innervation signs were also seen in the cervical and thoracic region. Genetic testing for C9orf72 was negative.

Considering there was focal onset of weakness (left hand) with progression to other regions of the body (bulbar and legs) with both upper (4 regions) and lower motor neuron signs (2 regions) with exclusion of other causes, we diagnosed her with ALS. Over the next year, progression of motor symptoms led to increased disability causing her to move into a nursing home.

Neuropsychological assessment

She initially underwent a brief neuropsychological assessment (ECAS, ALS-FTD-Q, and FAB). She scored just above cutoff on the ECAS total score, ALS-specific, and nonspecific parts. On the ECAS-visuospatial component she scored at the cutoff value. The FAB and ALS-FTD-Q scores were 17 and 9, respectively.

The interview with a knowledgeable proxy revealed that she seemed to be struggling with simple everyday tasks. For instance, she seemed to be unable to set the table and she struggled to get dressed.

When confronted with these observations the patient indeed acknowledged that she was struggling with relatively simple tasks. She was completely capable explaining how the table should be set. However, when she had to actually do it, arranging the objects in the right configuration was extremely challenging to her. If her attention was directed toward a spoon, she seemed to be unable to observe the plate. However, when pointed to the plate, it seemed she was no longer able to see the spoon (simultanagnosia). She also had problems getting dressed. After the neurological examination she struggled to put her sweater back on. In the end she did not succeed, finally saying she did not understand her sweater (dressing apraxia). She also said she did not feel things the way she used to. For example, she could not tell if she was wearing her watch around her wrist. Reading had also become problematic. She easily lost on which line she was, but experienced fewer problems when letters were bigger or when there was less text (visual crowding). Her handwriting had become less legible and she often did not know which letter should come next in a word. She could no longer type with two hands and she had also noticed her math skills, which used to be very good, had deteriorated considerably (acalculia). She was receiving additional care from nurses that visited her house twice a day. She was unable to recognize the nurses by face, but could do so based on their voices (prosopagnosia). She did not have an alien limb phenomenon, limb apraxia, myoclonus, oculomotor apraxia, or optic ataxia.

She had not noticed any significant changes in language, memory, or behavior, which was confirmed by the proxy. She did not express feelings of anxiety or depression. The cognitive complaints did not seem to be in-keeping with FTD. A full neuro-psychological assessment (NPA) and brain MRI were therefore ordered.

During the NPA she had trouble finding items on a piece of paper and would often get lost on pages. The NPA demonstrated marked deficits in visuospatial perception and visuoconstruction. The deficits in visuoconstruction caused problems in writing and drawing, and also affected the performance on tasks with visual components designed to assess other cognitive domains (e.g. trail making and Stroop test). Recognition of visual material (words and objects) was intact. No deficits were observed in language (working) memory, attention, executive functions, and praxis (full results in ). The cognitive profile was not considered to be compatible with FTD or typical AD (Citation2).

Table 1 Summary of findings on full neuropsychological evaluation.

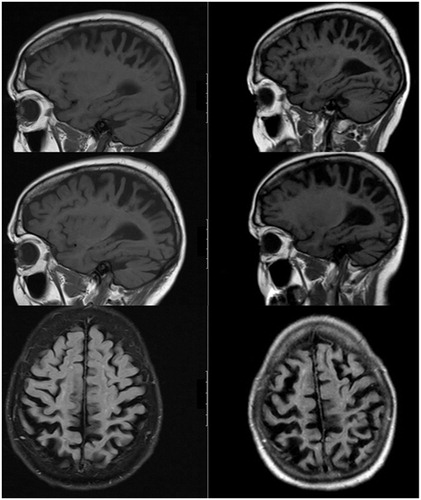

The MRI showed severe bilateral progressive atrophy of the parietal lobe (to some extent in the adjacent frontal and occipital regions; ).

Figure 1 Two MRI scans of the brain were performed with an interval of one year. The figure shows 3T T1weighted images of (A) the left hemisphere, (B) the right hemisphere, and (C) transverse slices. The initial scan shows some generalized atrophy, perhaps more prominently of the parietal lobe, but which was considered to be within the range of normal for her age. The follow-up MRI (at time of second opinion) showed progressive bilateral atrophy of the parietal lobes in particular (Koedam score grade 3) and to some extent in the adjacent frontal and occipital regions. The hippocampus did not appear atrophic (MTA grade 1). There some white matter changes (Fazekas grade 2). There were no mass lesions and there was no enhancement after the administration of gadolinium.

As diagnostic criteria were met we diagnosed her with PCA syndrome (Citation3):

There was an insidious onset, with gradual progression and prominent early disturbance of visual with or without other posterior cognitive functions

≥3 of the required features; prosopagnosia, dressing apraxia, simultanagnosia, and acalculia.

There was relative sparing of behavior and personality, speech and nonvisual language functions, anterograde memory function, and executive functions.

Neuroimaging showed predominant occipito-parietal atrophy.

There was no evidence for an alternative identifiable cause for cognitive impairment such as a brain tumor, mass lesion, vascular disease, afferent visual cause, psychiatric disease, or metabolic disorder.

Discussion

While cognitive deficits within the FTD-spectrum are common in ALS, this is to our knowledge the first case of ALS-PCA. Although the etiology of PCA is unclear, it is generally considered related to AD and tau-pathology (Citation2,Citation3). Therefore a relation to ALS seems unlikely given its association with FTD and TDP-43-pathology (Citation1). As we are a large ALS clinic (>300 new referrals annually), we acknowledge the possibility that the co-occurrence with PCA could be coincidental.

However, we also hypothesize that ALS-PCA might be a novel phenotype. Multiple imaging studies show profound (asymptomatic) parietal atrophy in ALS (with and without C9orf72 repeat expansions) (Citation4,Citation5). It seems reasonable to assume that severe parietal atrophy would have neuropsychological consequences, especially for visuospatial processing. In most imaging studies, however, neuropsychological testing was not extensive and limited to screeners. Although these screeners (ECAS, ALS-CBS) (Citation6,Citation7) are very useful, also in the clinic, they are designed to give a quick overview across multiple domains and encompass only one or two tests per domain. Subtle deficits may therefore be missed. In particular, in the visuospatial domain as most ALS-screeners understandably focus on frontotemporal functions. As seems to be the case here, where the three visuospatial tests in the screener came back normal, but severe quite deficits were missed (patients JOLO score is at the first percentile).

We feel that a single (and perhaps unusual) case does not warrant the coining of a new phenotype. With this case report, we aim to encourage others to report similar cases and perform more extensive neuropsychological evaluation of parietal functions, in particular in cases with parietal atrophy. Whether ALS-PCA is indeed a novel or under-recognized (endo)phenotype requires additional research.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Burrell JR, Halliday GM, Kril JJ, Ittner LM, Götz J, Kiernan MC, et al. The frontotemporal dementia-motor neuron disease continuum. Lancet. 2016;388:919–31.

- Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, et al. Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: the IWG-2 criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2014;6:614–29.

- Schott JM, Crutch SJ. Posterior cortical atrophy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2019;25:52–75.

- Walhout R, Schmidt R, Westeneng HJ, Verstraete E, Seelen M, van Rheenen W, et al. Brain morphologic changes in asymptomatic C9orf72 repeat expansion carriers. Neurology. 2015;85:1780–8.

- Westeneng HJ, Walhout R, Straathof M, Schmidt R, Hendrikse J, Veldink JH, et al. Widespread structural brain involvement in ALS is not limited to the C9orf72 repeat expansion. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1354–60.

- Abrahams S, Newton J, Niven E, Foley J, Bak TH. Screening for cognition and behaviour changes in ALS. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2014;5:9–14.

- Woolley SC, York MK, Moore DH, Strutt AM, Murphy J, Schulz PE, et al. Detecting frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS: utility of the ALS Cognitive Behavioral Screen (ALS-CBS). Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2010;11:303–11.