Abstract

Objective: To determine the current practice in genetic testing for patients with apparently sporadic motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MND/ALS) and asymptomatic at-risk relatives of familial MND/ALS patients seen in specialized care centers in the UK. Methods: An online survey with 10 questions distributed to specialist healthcare professionals with a role in requesting genetic testing working at MND/ALS care centers. Results: Considerable variation in practice was found. Almost 30% of respondents reported some discomfort in discussing genetic testing with MND/ALS patients and a majority (77%) did not think that all patients with apparently sporadic disease should be routinely offered genetic testing at present. Particular concerns were identified in relation to testing asymptomatic at-risk individuals and the majority view was that clinical genetics services should have a role in supporting genetic testing in MND/ALS, especially in asymptomatic individuals at-risk of carrying pathogenic variants. Conclusions: Variation in practice in genetic testing among MND/ALS clinics may be driven by differences in experience and perceived competence, compounded by the increasing complexity of the genetic underpinnings of MND/ALS. Clear and accessible guidelines for referral pathways between MND/ALS clinics and clinical genetics may be the best way to standardize and improve current practice, ensuring that patients and relatives receive optimal and geographically equitable support.

Introduction

Since the discovery of pathogenic variants in superoxide dismutase-1 (SOD1) in familial motor neurone disease/amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (MND/ALS) (Citation1), there has been an exponential increase in the number of monogenic causes of ALS. Currently, variants in over 20 genes have strong evidence for pathogenicity (Citation2–5), with an even greater number of genes in which variants are proposed to act as risk factors, accounting for some of the estimated heritability of ALS (Citation6). Moreover, pathogenic variants in more than one gene, which are individually sufficient to cause ALS, have been found to co-occur more frequently than expected by chance, further broadening the genetic etiology to include so-called oligogenic disease (Citation7).

Accompanying this evolving landscape of ALS genetics, the provision of optimal patient care must include an adequate discussion of disease etiology, counseling for patients and relatives regarding genetic testing, and knowledge of the appropriate pathways for molecular testing. Furthermore, the role of genetic testing in ALS is becoming increasingly relevant given that, despite our limited understanding of the pathophysiology, clinical trials with targeted genetic therapies for patients with monogenic disease are already taking place (Citation8,Citation9).

We conducted a survey of genetic testing in specialist ALS centers in the UK and the Republic of Ireland (ROI) to understand if ALS clinicians working in specialist centers feel appropriately skilled to include a full discussion of ALS genetics in their practice.

Methods

An ethically approved (Newcastle University ref. no. 9643/2020) 10-question online survey (Jisc, Bristol United Kingdom; Supplementary File 1) was disseminated through the UK ALS care center network and ROI via email, with support from the UK ALS Clinical Studies Group and the Motor Neurone Disease Association and remained open for 6 months. All members of ALS teams with a role in requesting genetic testing were invited to participate. Analysis and graphical representations were performed using Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Publisher and Prism/GraphPad.

Results

A total of 30 respondents from 21 ALS care centers completed the survey, 57% (17/30) of whom had both an academic and clinical appointment and the remainder an exclusively clinical role (43%;13/30). The majority (67%; 20/30) were accredited neurological specialists; 45% held professorships. One respondent was an ALS care coordinator.

Most respondents described their specialty as neurology with a subspecialty interest in ALS (27/30), two as neurology without subspecialty in ALS and one as clinical genetics.

Genetic testing in apparently sporadic ALS

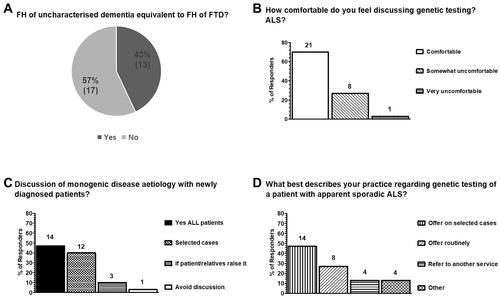

Seven questions aimed to determine individual practice and opinions regarding genetic testing in apparently sporadic disease (, Supplementary File 1), including views on whether a family history of “uncharacterised dementia” was equivalent to that of frontotemporal dementia (FTD), which might influence classification of disease as sporadic or familial.

Table 1 Seven questions in the survey were aimed at determining individual practice in genetic testing in patients with apparently sporadic disease.

The responses to these questions are summarized graphically in and . Whilst the majority (57%; 17/30) did not consider “uncharacterised dementia” equivalent to FTD in the family history, 43% (13/30) considered it equivalent to FTD, highlighting the difficulty in classifying ALS as sporadic or familial (). The majority (70%; 21/30) was comfortable discussing genetic testing in ALS () and 47% (14/30) routinely discuss the possibility of monogenic disease etiology and inheritance with newly diagnosed patients, whilst 40% (12/30) do so only if there are specific factors suggesting a genetic etiology (). 30% (9/30) reported some level of discomfort in discussing genetic testing in patients diagnosed with ALS ().

Figure 1 Current practice in genetic testing of apparently sporadic ALS in the UK as surveyed from 30 clinicians in 21 ALS care centers. (A) Classification of ALS into familial or sporadic disease remains variable with 57% (17/30) of clinicians considering that a family history (FH) of ‘uncharacterised dementia’ is not equivalent to a FH of FTD, whilst 43% (13/30) considered it equivalent. Additional comments, provided in Supplementary File 2, further highlight the lack of consensus and inherent variability in the classification of ALS into apparently sporadic or familial. (B) The majority of clinicians feel comfortable discussing genetic testing in ALS 70% (21/30); 27% (8/30) feel somewhat uncomfortable and 3% (1/30) very uncomfortable. (C) 47% (14/30) of clinicians discuss monogenic disease etiology with all newly diagnosed patients, 40% (12/30) do so on selected cases when certain factors suggest possible genetic etiology, 10% (3/30) only when the patient or relatives raise the topic and 3% (1/10) avoid the discussion. (D) The majority of clinicians (47%; 14/30) offer genetic testing to patients on selected cases when monogenic disease etiology is suspected, 27% (8/30) offer testing routinely to patients diagnosed with apparently sporadic disease and 13% (4/30) refer the patient to a different service, even if they had a discussion on the genetic etiology of ALS. Of the 13% (4/30) of respondents who took alternative action ("other"), 2/4 clarified that they do not refer as this would be a decision for the consultant in clinic, 1/4 commented that their practice in regard to accessing genetic testing was constrained due to commissioning arrangements and 1/4 reported that they would perform the test but subsequently refer to local or regional genetics services if the genetic test was positive (see free text comments Supplementary File 2).

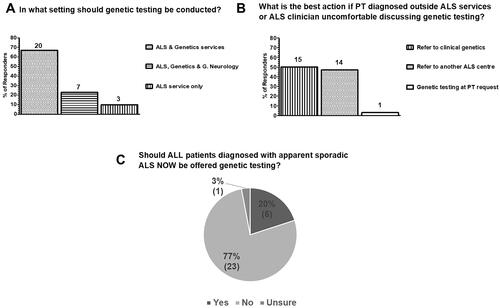

Figure 2 Current views on which setting genetic testing for ALS should be conducted and whether it is now time to test all patients with apparently sporadic disease in the UK as surveyed from 30 clinicians in 21 ALS care centers. (A) 67% (20/30) of clinicians considered that testing should be performed in the ALS services and, additionally, clinical genetics services. 23% (7/30) were of the opinion that genetic testing can be performed in the context of a general neurology clinic, or an ALS or clinical genetics service and 10% (3/30) considered that testing should only take place in the ALS services. (B) In regard to genetic testing, when a patient is diagnosed outside the ALS services or the ALS clinician is uncomfortable discussing genetic testing, 50% (15/30) of respondents considered that the best action is to refer patients to clinical genetics, 47% (14/30) to a different ALS care centre with expertise in genetics and 3% (1/10) considered that sending the genetic test at the patient’s request is the most appropriate action. (C) The majority of clinicians (77%; 23/30) considered that, at present, it is not appropriate to offer genetic testing to all patients diagnosed as apparently sporadic ALS routinely. 20% (6/30) considered that all patients diagnosed with apparently sporadic disease should now be offered testing and 3% (1/30) were unsure.

Almost a third (27%; 8/30) of respondents offered genetic testing to patients with apparently sporadic disease routinely, 47% (14/30) on a case-by-case basis, 13% (4/30) refer to local clinical genetics services and a further 13% (4/30) another service or colleague for consideration of genetic testing (). Free text comments (Supplementary File 2) provide further insight into factors that influence an individual’s approach to genetic testing in apparently sporadic disease. These included the fact that some only commonly performed genetic testing in familial disease, and thus were less comfortable doing so in apparently sporadic cases, and the increasing complexity of ALS genetics, including incomplete penetrance and variants of unknown significance (VUS), which add to the challenge of communicating results to patients, given the limited level of understanding of genetic concepts, in general, in the patient population (Citation10).

The majority (67%; 20/30) considered that genetic testing in ALS should be conducted in specialist ALS clinics or clinical genetics services, 23% (7/30) viewed a general neurology clinic as an acceptable setting for conducting genetic testing (in addition to ALS and clinical genetics services), and 10% of those who responded (3/30) considered that genetic testing should only be offered in the context of an ALS clinic (). When a diagnosis is achieved outside the setting of an ALS clinic, or if the ALS clinician feels uncomfortable discussing genetic testing, there was an almost even split with 50% (15/30) reporting that the best action is to refer to clinical genetics and 46% (14/30) to another ALS care center. A single respondent considered it is appropriate to proceed to genetic testing solely on the basis of the patient’s request ().

The majority 77% (23/30) of respondents did not consider that, presently, genetic testing should be offered to all patients diagnosed with apparently sporadic ALS ().

Genetic testing in at-risk individuals for monogenic ALS

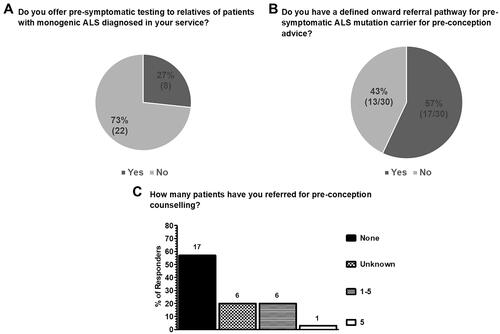

Three questions () were aimed at determining practice regarding predictive testing, specifically in relatives of ALS patients in whom a monogenic etiology is confirmed, and whether pre-conception counseling services are available for asymptomatic pathogenic variant carriers.

Table 2 Three questions were aimed at determining individual practice in genetic testing in asymptomatic/pre-symptomatic at-risk relatives of patients with monogenic MND/ALS.

A minority (27%; 8/30) offered pre-symptomatic testing for relatives of patients with monogenic ALS (), despite the majority reporting that they have an onward referral pathway for pre-conception advice for those carrying pathogenic variants (57%; 17/30 – ). When the answers to the question on whether pre-symptomatic testing was offered and whether there was a defined pathway for pre-conception advice are analyzed by center (), discordance between respondents at the same center () suggests individual variation in practice both with respect to pre-conception testing and interpretation of whether a referral pathway has been defined by respondents from the same center.

Figure 3 Current practice in genetic testing and counseling services for pre-symptomatic relatives of patients with monogenic ALS (at-risk individuals) and pre-symptomatic carriers in the UK as surveyed from 30 clinicians in 21 ALS care centers. (A) Genetic testing for asymptomatic/pre-symptomatic relatives of patients with monogenic disease is only offered by 27% (8/30) clinicians, whilst 73% (22/30) do not offer this service. (B) 57% (17/30) of respondents reported having an onward referral pathway for pre-symptomatic pathogenic variant carriers for pre-conception advice whilst 43% (13/30) reported not having an onward referral pathway for this purpose. (C) Most clinicians have never referred a patient carrying an ALS pathogenic variant for pre-conception counseling (57%; 17/30), 20% (6/30) were not able to answer and only 23% (7/30) have referred patients for pre-conception counselling (6/7 between 1 and 5 patients and 1/7 5 patients).

Table 3 Tabulated answers for each respondent, in each care centre (care centre 1-21; CC1-CC21) to the question “Do you have a defined onward referral pathway (even if not written as a protocol) for pre-symptomatic MND/ALS pathogenic variant carriers for pre-conception advice?”.

Clinicians working in ALS care centers have limited experience in referring patients for pre-conception counseling, with 57% (17/30) having never made a referral. The highest number of patients referred by an individual respondent was 5 ().

Discussion

Our survey demonstrates significant variation in genetic testing in apparently sporadic ALS. The interpretation of a family history of “uncharacterised dementia” and whether this is equivalent to that of FTD diverged significantly between ALS specialists (), in agreement with the lack of consensus in classifying disease as familial or sporadic reported in 2017 (Citation11). In the UK, clinical services are organized regionally; hence, the skill mix of clinicians at ALS care centers will vary according to the region. Thus, the different degrees of expertise between regional clinicians and the time available in clinic to discuss complex issues may influence how a family history is taken, whether a pedigree is carefully drawn, and how “uncharacterised dementia” is interpreted and considered in categorizing ALS. Furthermore, consideration of this complex matter should be taken into account in future guidelines and regional service development. Only one respondent described their specialty as clinical genetics, suggesting these specialists are not commonly part of multidisciplinary ALS clinics. Therefore, the practice of clinical geneticists is not reflected in this study. Whilst almost one in three respondents reported some discomfort in discussing genetic testing in ALS (), this may reflect variation in expertise within clinical teams, together with the changing landscape of ALS genetics. The latter is likely to be the most significant factor underpinning the observation that less than half of those who responded to the survey discuss monogenic disease etiology routinely with newly diagnosed patients.

A majority of respondents in this study did not consider that all patients diagnosed with apparently sporadic ALS should be offered testing (), which may be in contrast to the increasing expectations of patients, who have been previously shown to hold stronger views than clinicians that genetic test results are likely to bring useful information (Citation12).

Genetic testing in apparently sporadic ALS: considerations for future practice

Despite the pitfalls in classifying ALS as sporadic or familial disease, approximately 7–15% (Citation13,Citation14) of patients with apparently sporadic disease have been reported to have a definite pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant, and almost a further 24% a VUS in the absence of a pathogenic variant (Citation14). At present, the published data suggest that younger age of onset (younger than 50) increases the probability of monogenic disease etiology (Citation13); therefore, genetic testing of younger patients is more likely to identify apparently sporadic disease of monogenic etiology. Whilst the relationship between age of onset and probability of carrying a pathogenic variant remains uncertain, useful novel data will hopefully emerge from the large scale whole genome sequencing study in ALS (Citation15). However, studies based on samples from younger patients (Citation14) may be less representative of the patient cohort in ALS care centers (mean age at diagnosis was 67.91 ± 1.45 years at the Newcastle ALS care and research center in 2020). While we did not ask ALS clinicians specifically about factors that would influence their decision in offering genetic testing on a case-by-case basis, it is reasonable to infer age would be a factor, reflecting evidence in the literature and, possibly, individual experience.

Presently, disease etiology does not influence clinical management but increasingly influences participation in clinical trials, particularly those that are specific for monogenic ALS (Citation8,Citation9). Moreover, stratifying patients by genotype for therapeutic trials, even if therapy is not gene specific, may have advantages (Citation16). On that basis, more widespread testing in apparently sporadic disease might be indicated, in the interests of patient autonomy. However, there are significant workload implications to such an approach, including a requirement for a clear understanding of the role of the test itself and a discussion of VUS and the penetrance of individual pathogenic variants, all of which are relevant both for the patient and at-risk relatives. These will influence not only factors associated with family planning, but also possibly decisions regarding employment and personal finances; despite the current code of conduct for taking life insurance in the UK not requiring disclosure of predictive testing results in asymptomatic individuals at-risk of ALS (Citation17), patients have been shown to often misinterpret the significance of VUS (Citation18). The duty of counseling patients, using the best available evidence at the time, supporting them through the entire process and dealing with the results, lies with the clinician (Citation19).

In practice, although ancillary investigations contribute to the diagnostic process, ALS remains in essence a clinical diagnosis (Citation20). Formal diagnostic criteria have been formulated and revised, in the main aimed at simplifying and broadening access to therapeutic trials (Citation21).

For most ALS patients, who have apparently sporadic disease, etiology is not monogenic and even in those with familial disease, a monogenic cause is still not identified in approximately 30% (Citation22). This is pivotal to any discussion when counseling patients regarding genetic testing. In spite of this, it is clear that some clinicians use genetic testing as a diagnostic tool (Citation23), highlighting the need for clear guidance regarding the role and value of such testing. This is particularly important given the wide variation in expertise demonstrated by our survey. Even for the expert, a discussion on VUS or variable gene penetrance with patients or relatives is not straightforward. It is the view of the authors, in agreement with the previously expressed views of a group of experts (Citation24), that genetic testing has no role in ALS diagnosis, despite the suggestion that it might provide supportive information for an ALS diagnosis in recently proposed diagnostic criteria (Citation21).

Genetic testing in at-risk individuals for monogenic ALS: considerations for future practice

In contrast to testing patients with an established clinical diagnosis, predictive testing in ALS carries much higher uncertainty given the variable and age-dependent penetrance of gene variants associated with monogenic disease (e.g. the hexanucleotide expansion in C9orf72) (Citation25,Citation26). This may explain why, at present, most respondents do not offer genetic testing for asymptomatic relatives of patients with monogenic disease. However, the possibility of genetic testing for unaffected relatives of ALS patients has been offered in the UK through clinical genetics services. A summary of practice encompassing a 5-year period, involving 10 clinical genetics centers and 301 referrals (70 affected patients and 231 unaffected relatives) has been published (Citation27). Over 60% of referrals for genetic testing originated from primary care directly to clinical genetics services and only 9% of unaffected individuals were referred to neurology (Citation27). Therefore, despite a small number of unaffected individuals being assessed by a neurologist prior to referral (28/231), it can be inferred that some patients found to carry a pathogenic variant went through the entire process without any discussion involving an ALS-focused neurologist. If this inference is correct, these patients did not have the opportunity to hold an expert discussion about the clinical aspects of the disease for which they are atrisk, including its probable clinical evolution and management, which would be considered suboptimal, both in terms of the counseling and the informed consent process.

Discussing a VUS is an extremely challenging area, particularly in the setting of clinicians with a diverse range of knowledge and skills. Suboptimal counseling can lead to unnecessary anxiety, anguish and have a negative impact on healthy individuals who may never develop ALS. One such example of this complexity is with the D91A variant of SOD1, which has recently been shown unambiguously not to cause SOD1-related ALS when heterozygous through a clinical and neuropathological case study (Citation28). Despite the evidence to the contrary, when this variant is identified in ALS patients, it continues to be proposed as pathogenic and leading to a monogenic dominant form of the disease (Citation29) rather than being acknowledged as a VUS.

The implications for reproductive planning are a further critical area of discussion in predictive testing. Thus, formal onward referral pathways for pre-conception advice should be accessible to ALS care centers, given the relative inexperience of ALS clinicians in referring patients for pre-conception advice (). Another emerging consideration for predictive testing is in facilitating recruitment to trials of genetic therapies offered during the pre-symptomatic stage. A trial involving pre-symptomatic carriers of pathogenic variants in SOD1 (Citation30), which may lead to increasing demand, is already at an advanced stage of set-up, thereby emphasizing the need to address the current gaps in service provision.

Whilst this survey did not assess opinion on the preferred setting for predictive testing, it is clear that much of the expertise in this area resides in clinical genetics services and is, at present, limited in ALS care centers. Integrated referral pathways, where there is an ability to accommodate multiple visits for counseling in genetics clinics, incorporating ALS clinicians better equipped to discuss the clinical course of ALS and the role of clinical trials and future therapies, may represent the best model. Additionally, in many cases, ALS clinicians may also be better prepared for more nuanced discussions regarding penetrance, avoiding the temptation to utilize well established frameworks (such as that in counseling for Huntington’s disease, a fully penetrant disease), which has been advocated by genetics services (Citation27).

Genetic testing in ALS: planning future practice

Recent changes to genetic testing in the UK National Health Service (NHS) are an attempt to standardize the process and widen access (Citation31) and are likely to lead to more frequent testing in symptomatic patients, with the downstream effect of increasing demand for predictive testing in relatives of patients with monogenic ALS. The substantial variation in attitude and practice in testing patients with apparently sporadic disease and at-risk relatives reported here, together with the limited experience of referring patients for pre-conception counseling, may reflect differing expertise in genetics amongst ALS clinicians and the increasing complexity of ALS genetics.

Variation in the use of predictive genetic testing is not restricted to the UK. A survey of ALS-based practice in Canada revealed similar variance (Citation32). Certain aspects of practice are applicable across all healthcare systems.

A pivotal and universal principle supported by current evidence is that genetic testing in ALS does not have a role in diagnosis and, therefore, should not be conducted as part of a diagnostic work-up, but instead to determine disease etiology. Taking this principle as a starting point, a framework has been proposed which can be used to support individual practice in the UK (Citation24). Nevertheless, applying the proposed framework requires adequate clinical knowledge and experience. Specific guidelines that support clinicians across all levels of experience are not presently available. Moreover, guidelines should take into account the penetrance of pathogenic variants in different genes and the process to recall patients and discuss classification changes in VUS, important issues which were not addressed by the present survey and need consideration.

With emerging trials of specific therapies for monogenic ALS, widespread access to genetic testing in the NHS, and increasing interest from patients and relatives on genetics, discussions surrounding testing and the number of patients being tested is set to rise sharply. Developing specific guidelines to support clinicians and patients in decision making, based on a cooperative approach between neurologists and clinical geneticists, accompanied by the development of accessible pre-conception services appears a sensible way of addressing current and future needs of ALS patients and their relatives, concomitantly supporting clinicians in applying best practice. Guidelines should be specific to UK and ALS genetic testing, thus acknowledging the organization of the NHS and supporting the role of the relevant specialists (neurologists, genetics counselors, and clinical geneticists). Developing consensus guidelines will support doctors in following appropriate pathways so that patients and relatives can have access to an accurate and comprehensive discussion about testing. Moreover, consensus guidelines will also support those healthcare professionals who are uncomfortable in the field of ALS genetics from feeling that they ought to proceed to testing at the patient’s request, given that testing is now available through the NHS to all doctors and other practitioners (Citation31).

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (96.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21 KB)Declaration of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in this article and its supplementary files in an anonymised format. Individualized data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy and anonymity of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rosen DR, Siddique T, Patterson D, Figlewicz DA, Sapp P, Hentati A, et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 1993;362:59–62.

- Chia R, Chiò A, Traynor BJ. Novel genes associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: diagnostic and clinical implications. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17:94–102.

- Renton AE, Chiò A, Traynor BJ. State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:17–23.

- Lill CM, Abel O, Bertram L, Al-Chalabi A. Keeping up with genetic discoveries in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: the ALSoD and ALSGene databases. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12:238–49.

- Abel O, Powell JF, Andersen PM, Al-Chalabi A. ALSoD: a user-friendly online bioinformatics tool for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1345–51.

- Al-Chalabi A, Fang F, Hanby MF, Leigh PN, Shaw CE, Ye W, et al. An estimate of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis heritability using twin data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1324–6.

- Van Blitterswijk M, Van Es MA, Hennekam EAM, Dooijes D, Van Rheenen W, Medic J, et al. Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:3776–84.

- US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Identifier: NCT03070119, an extension study to assess the long-term safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and effect on disease progression of BIIB067 administered to previously treated adults with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis caused by superoxide dism. Bethesda (MD): NIH; 2017. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03070119?recrs=d&type=Intr&cond=ALS&draw=3&rank=14

- US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Identifier: NCT03626012. A phase 1 multiple-ascending-dose study to assess the safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of BIIB078 administered intrathecally to adults with C9ORF72-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Bethesda (MD): NIH; 2018. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03626012?recrs=d&type=Intr&cond=ALS&draw=3&rank=15

- Condit CM. Public understandings of genetics and health. Clin Genet. 2010;77:1–9.

- Vajda A, McLaughlin RL, Heverin M, Thorpe O, Abrahams S, Al-Chalabi A, et al. Genetic testing in ALS: a survey of current practices. Neurology 2017;88:991–9.

- Klepek H, Nagaraja H, Goutman SA, Quick A, Kolb SJ, Roggenbuck J. Lack of consensus in ALS genetic testing practices and divergent views between ALS clinicians and patients. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2019;20:216–21.

- Roggenbuck J, Palettas M, Vicini L, Patel R, Quick A, Kolb SJ. Incidence of pathogenic, likely pathogenic, and uncertain ALS variants in a clinic cohort. Neurol Genet. 2020;6:e390–7.

- Shepheard SR, Parker MD, Cooper-Knock J, Verber NS, Tuddenham L, Heath P, et al. Value of systematic genetic screening of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92:510–8.

- Consortium PMAS. Project MinE: study design and pilot analyses of a large-scale whole-genome sequencing study in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Eur J Hum Genet 2018;26:1537–46.

- Van Eijk RPA, Jones AR, Sproviero W, Shatunov A, Shaw PJ, Leigh PN, et al. Meta-analysis of pharmacogenetic interactions in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis clinical trials. Neurology 2017;89:1915–22.

- United Kingdom Government and Association of British Insurers. Code on genetic testing and Insurance: a voluntary code of practice agreed between HM Government and the Association of British Insurers on the role of genetic testing in insurance. 2018. p. 1–18. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/code-on-genetic-testing-and-insurance. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/code-on-genetic-testing-and-insurance

- Clift K, Macklin S, Halverson C, McCormick JB, Abu Dabrh AM, Hines S. Patients’ views on variants of uncertain significance across indications. J Community Genet. 2020;11:139–45.

- Turner MR, Al-Chalabi A, Chio A, Hardiman O, Kiernan MC, Rohrer JD, et al. Genetic screening in sporadic ALS and FTD. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2017;88:1042–4.

- Turner MR, Talbot K. Motor neurone disease is a clinical diagnosis. Pract Neurol. 2012;12:396–7.

- Shefner JM, Al-Chalabi A, Baker MR, Cui LY, de Carvalho M, Eisen A, et al. A proposal for new diagnostic criteria for ALS. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131:1975–8.

- Chio A, Calvo A, Mazzini L, Cantello R, Mora G, Moglia C, et al. Extensive genetics of ALS : a population-based study in Italy. Neurology 2012;79:1983–9.

- Stenson K, Nicholson K, Al-Chalabi A, Mellor J, Wright J, Gibson G, et al. Patterns of genetic testing among patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS): real-world results from the United States and Europe. Platf commun Abstr B - 32nd Int Symp ALS/MND (complete printable file). Amyotroph Lateral Scler Front Degener 2021;22:17–8.

- Dharmadasa T, Scaber J, Edmond E, Marsden R, Thompson A, Talbot K, et al. Genetic testing in motor neurone disease. Pract Neurol. 2022;22:107–16.

- Majounie E, Renton AE, Mok K, Dopper EGP, Waite A, Rollinson S, et al. Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:323–30.

- Murphy NA, Arthur KC, Tienari PJ, Houlden H, Chiò A, Traynor BJ. Age-related penetrance of the C9orf72 repeat expansion. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–7.

- Cairns LM, Rankin J, Hamad A, Cooper N, Merrifield K, Jain V, et al. Genetic testing in motor neuron disease and frontotemporal dementia: a 5-year multicentre evaluation. J Med Genet. 2022;59:544–8.

- Feneberg E, Turner MR, Ansorge O, Talbot K. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with a heterozygous D91A SOD1 variant and classical ALS-TDP neuropathology. Neurology 2020;95:595–6.

- Farrugia Wismayer M, Farrugia Wismayer A, Pace A, Vassallo N, Cauchi RJ. SOD1 D91A variant in the southernmost tip of Europe: a heterozygous ALS patient resident on the island of Gozo. Eur J Hum Genet. 2022;30: 856–9.

- US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Identifier: NCT04856982, a phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a longitudinal natural history run-in and open-label extension to evaluate BIIB067 initiated in clinically presymptomatic adults with a confirmed superoxide dismutase 1 mutation. Bethesda (MD): NIH; 2021. Available from: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/study/NCT04856982?term=SOD1&cond=ALS&draw=2&rank=8

- National Health Service (NHS) England. National genomic test directory testing criteria for rare and inherited disease. 2021; p. 280. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-genomic-test-directories/%0Ahttps://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-genomic-test-directories/%0Ahttps://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Rare_and_Inherited_Disease_Eligibility_Criteria_A

- Salmon K, Anoja N, Breiner A, Chum M, Dionne A, Dupré N, et al. Genetic testing for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis in Canada–an assessment of current practices. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2022;23:305–12.