Despite being a complex area for pharmaceutical and biotech companies to navigate from an ethical and practical perspective, having a well thought through, workable and organizationally aligned policy in place on how to respond to requests for innovative treatments in development can have benefits across stakeholders and ultimately for patients often in desperate need.

The debate surrounding access to investigational treatments rages on, involving patients and patient’s families, healthcare providers, regulators, and industry, and is of particular relevance to the orphan disease space.

As of May 2016, 28 [Citation1] states in the U.S. have passed ‘right to try’ laws that permit pharmaceutical and biotech companies to provide terminally-ill patients with investigational drugs without going through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s expanded access process [Citation2]. These new laws, however, do not require manufacturers who own these drugs to provide access and though they are unlikely to provide an effective mechanism by which patients may access investigational drugs, they do serve to shine a brighter spotlight on an already fiercely debated area.

The benefits and risks of providing access to medicines still in development to patients in need will continue to be the subject of much controversy as the demand from patients and their caregivers appears to be increasing, with high-profile cases in the press and social media having gained huge attention over recent years [Citation3].

This trend is likely to continue as pharmaceutical and biotech companies focus on developing medicines in areas of high unmet need and as patients and families of the sick monitor Pharma pipelines and developments more closely.

The necessity for manufacturers to have a robust strategy and policy in place to deal with requests from patients and healthcare providers in a clear and transparent manner is hard to deny.

‘Managed Access Programs’ (MAPs) allow access to medicinal products that are not commercially available in a patient’s country, either because they are in clinical development, are licensed but not commercially available in the patient’s country, are unlicensed in the patient’s country although licensed elsewhere, or have been withdrawn. The use of various other nomenclature at both a country, health authority, and company level is a frequent cause of confusion, with programs often also referred to as ‘Named Patient’, ‘Compassionate Use,’ ‘Early Access,’ ‘Pre-Approval Access,’ and ‘Expanded Access’ [Citation4]. Indeed, an Expanded Access Program (EAP) and an Early Access Program (EAP) are not to be confused with an Expedited Access Pathway (EAP) recently introduced by the FDA! [Citation5]. The confusion is heightened further as the same terms can mean different things in different countries and settings, e.g. what ‘Compassionate Use’ means in Germany is very different to what the term means in Brazil in terms of the regulatory pathways, funding routes, and ultimately what this means for patient access to treatment.

Providing access to investigational medicines can be challenging for pharmaceutical and biotech companies, with much confusion and many misconceptions about what is and is not possible. MAPs differ fundamentally from clinical trials. The primary focus of a clinical trial is demonstration of safety and efficacy, whereas a MAP is focused upon treating an unmet patient need. That’s not to say that important real-world data cannot be collected with the right planning and system support (as reinforced in the following) but patient access to treatment should always remain the fundamental driver. Given the differences between the two, it is not surprising that the skills, experience, and infrastructure necessary to implement and manage a successful MAP vary significantly from those required for clinical trial execution. This is particularly true when a pharmaceutical or biotech company is approaching the issue on a global scale, where differences in regulations, logistical challenges, and reimbursement mechanisms are multiple and complex.

As mentioned earlier, the primary objective for implementing such programs must always be to provide access for patients with unmet medical need. However, these programs also provide opportunities for pharmaceutical and biotech companies to

Ensure all requests for access for both ‘eligible’ and ‘non-eligible’ patients are responded to in a compliant, consistent, and timely manner;

Ensure treating physicians are correctly educated about appropriate use of the product; and

Gather ‘real-world’ data about the use of a drug in a wider population that better reflect the patient groups in which the product will eventually be utilized in the event the drug receives regulatory approval.

Real-world data generation during a MAP can be a very strong tool when collected and used appropriately. For example, in the orphan disease setting, where patient numbers in clinical trials may be relatively low, a MAP presents an ideal opportunity to gather crucial information. Such data could assist in demonstrating product value, potentially be utilized in Health Technology Assessments, supplement market access submissions, and may even play a role in adaptive licensing or managed entry agreements. Compliant, prospective data capture during a MAP is an enormous, and as yet relatively untapped resource, which has the potential to deliver significant benefits for pharmaceutical and biotech companies, regulators, and ultimately Health Care Professionals and patients.

Many pharmaceutical and biotech companies have placed or are currently putting plans in place to establish a transparent and clear policy to be able to deal with requests for their innovative products, from both an internal and external perspective. The companies that do this most successfully have understood that a complete organizational alignment is required involving multiple stakeholders and innovative thinking. The policy should always reflect the company’s corporate ethos and be supported by appropriate governance and infrastructure across the business. At the same time, practical implementation of any policy is a surprisingly often overlooked fundamental aspect. Demand for access can come at a time when other activities are consuming internal resources such as execution of pivotal clinical trials or gaining of marketing approval.

Various pilot projects across industry are underway to establish fair and transparent mechanisms and recommendations on extremely difficult ethical decisions related to early access including J&J’s independent review panel model coming to the end of its initial pilot [Citation6].

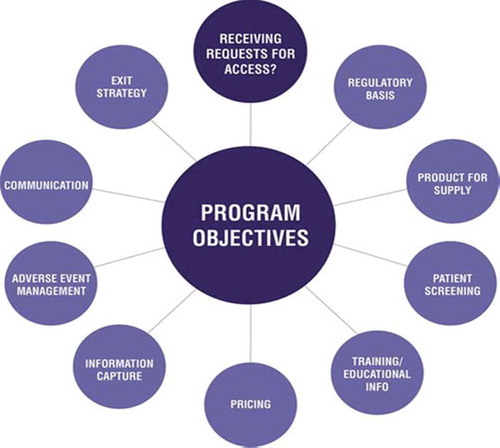

In order to ensure the successful development and implementation of a program, safeguard patients, and mitigate risk, a number of factors must be considered. . summarizes the range of considerations that must be taken into account to help ensure a successful access program.

The exact design and scope of any access program will depend on expected demand, regulatory feasibility, the license status of the product, necessary drug pricing structure, as well as company strategy, costs, and product supply.

Whilst there are numerous considerations and complexities in setting up and implementing a successful MAP, it is perfectly possible to do so given the right planning, collaboration, and focus.

The priority for all stakeholders remains the research and subsequent provision of safe and effective approved treatments for patients in need as quickly as possible. However, regardless of recent efforts such as the Right to Try movement, there is also no doubt that patients and healthcare providers facing limited options who are demanding access to treatments in development are frustrated as they try to navigate their way to access.

Delivering the right medicine, to the right patient, at the right time is wholly appropriate in this context, and whilst this concept fundamentally acknowledges that it is not always in the patient’s best interest to have access to an unapproved medication, pharmaceutical and biotech companies with promising products in their pipeline will be well advised to have a clear and workable strategy in place to deal with requests for these treatments.

The debate on patient access to unapproved treatments is set to continue.

While the initiation and management of an access program can be challenging and requires careful assessment and planning, the benefits to patients, healthcare providers, and sponsoring companies are immeasurable. Well-run programs provide an ethical and regulatory-compliant pathway for access to new treatments by patients with serious conditions and unmet medical needs. These programs also enable the building of relationships with prescribers, provide the opportunity to gather valuable real-world data, and can help address any challenges prior to the product being commercially launched. MAPs can vary considerably in scope and include anything from a handful to many thousands of patients and should be viewed with a global perspective in mind.

As more and more companies are realizing, dealing with requests from patients and healthcare providers should be considered early on in development planning in order that robust plans are put in place to address these needs and avoid challenges further down the pathway.

Whilst opinion is often divided in this highly emotive area, continued multi stakeholder collaboration is needed in order to provide patients with orphan diseases safe and effective treatments both in the long and in the short term.

There is no doubt that pharmaceutical and biotech companies are taking their responsibilities within the area of Early Access very seriously indeed. This is illustrated through their continued efforts to design and align organizational structure and culture to strategies and policies that are clear, transparent, and fair to patients.

Having worked in this space for many years, I am constantly reminded of the dramatic positive impact early access to critical treatments can have on the lives of patients and their families. I am also well aware of the potential risks that need to be well thought through and managed in order to provide access in a timely and compliant manner to the right patients and to compliment and support, rather than disrupt, development pathways.

The ethical and practical considerations in this area are complex and wide reaching, particularly when dealt with on a global scale. As of April 2016, I am not aware (having sought evidence) of a single patient who has received a treatment utilizing high-profile Right to Try laws in the U.S. This statement somewhat speaks for itself.

I am a member of the New York University Langone Medical Center Working Group on Compassionate Use and Pre-Approval Access in order to further understand the complexities of pre-approval access from an ethical and practical perspective with a view to helping more patients and families often in desperate situations.

I predict that it won’t be very long before Early Access is considered as a fundamental element of all early routine planning alongside clinical trial development, a shift in thinking and practice I (alongside I suspect the Orphan disease community) will welcome.

Declaration of interest

Tom works for Idis Managed Access, a part of the Clinigen Group. The Company partners with Pharmaceutical and Biotech Companies in devising early access strategy and implementing global programs. The author has no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Additional information

Funding

References

- US senator introduces a ‘Right to Try’ bill for desperate. By Ed Silverman (Pharmalot). [ cited 2016 May 10]. Available from: patientswww.https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2016/05/10/fda-experimental-drugs-right-to-try/.

- Expanded Access to Investigational Drugs. What physicians and the public need to know about FDA and corporate processes. Paige E. Finkelstein. [ cited 2015 Dec]. Available from: www.http://www.fda.gov/ForPatients/Other/ExpandedAccess/ucm20041768.htm.

- The hidden cost of crowd-sourcing a cure. Helen Ouyang. [ cited 2016 Jun]. Available from: www.http://harpers.org/archive/2016/06/hashtag-prescription/http://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12916-016-0568-8.

- Global access programs: a collaborative approach for effective implementation and management. Debra Ainge, Suzanne Aitken, Mark Corbett, David De-Keyzer in Pharmaceutical Medicine. 2015;29(2):79–85. [cited 2016 July 22]. Available from: http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40290-015-0091-9.

- Lungpacer Medical, Inc. Receives expedited access pathway designation from FDA for the Lungpacer diaphragm pacing system. [ cited 2016 May 11]. Available from: http://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/lungpacer-medical-inc-receives-expedited-access-pathway-designation-from-fda-for-the-lungpacer-diaphragm-pacing-system-300266364.html.

- J&J hopes to change the paradigm on compassionate use review. Ed Miseta. [cited 2016 Jan]. Available from: https://www.lifescienceleader.com/doc/j-j-hopes-to-change-the-paradigm-on-compassionate-use-review-0001.