ABSTRACT

Background: Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) is a disease caused by impaired lipoprotein lipase function and characterized by chylomicronemia, reduced quality of life (QoL) and risk of pancreatitis. The aim of the current study is to assess if QoL can be improved by patients being connected to other patients.

Methods: Respondents (N = 50) categorized into 3 groups (actively connected, passively connected and non-connected) self-reported their current or comparative assessments of QoL before and after connection with FCS-focused support organizations using a customized retrospective web-based survey.

Results: Connected respondents showed significantly improved perceptions of overall health, disease severity, motivation to take care of health and emotional well-being (p ≤ 0.05). Any level of connection produced noticeable benefits, but active connection in the form of regular interaction with other patients reported the greatest improvements. Additionally, respondents reported higher levels of satisfaction with their primary treating physician after being connected. The majority of patients (62%) reported joining support groups following referrals from their physicians.

Conclusions: Similar to other disease states, connecting with other patients with FCS had a positive impact on aspects of quality of life. Physicians may play a central role in referring their patients with FCS to support groups.

1. Introduction

Familial chylomicronemia syndrome (FCS) is a disease caused by impaired lipoprotein lipase (LPL) function and characterized by chylomicronemia, and increased risk for recurrent episodes of acute, potentially fatal, pancreatitis. LPL is the enzyme that helps to break down chylomicrons, through hydrolysis of plasma triglycerides (TG) [Citation1]. Because 90% of chylomicron particles consists of TG, the inherited deficiency in LPL or the proteins needed for LPL function in FCS results in extremely high (> 880 mg/dL) plasma TG levels [Citation1].

FCS, formerly referred to as lipoprotein lipase deficiency (LPLD) in some literature, is accompanied by significant disease burden, including acute pancreatitis, recurrent abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, eruptive xanthomas, lipemia retinalis, and fatigue [Citation2]. Acute pancreatitis presents the most significant risk in patients with FCS, with significant complications including potentially fatal acute pancreatitis [Citation3]. Approximately 67% [Citation4] to 76% [Citation5] of patients with FCS have experienced acute pancreatitis. In a large prospective study [Citation6] conducted in a cohort of 201 patients with acute pancreatitis, researchers showed that outcomes for patients with hypertriglyceridemia-induced acute pancreatitis are more severe with worse outcomes than pancreatitis of other etiologies. This study [Citation6] demonstrated that compared to acute pancreatitis in patients with normal TG levels (< 150 mg/dL), the acute pancreatitis in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia (TG > 1000 mg/dL) resulted in longer median hospital stays, increased need for intensive care, a higher rate of pancreatic necrosis, more frequent persistent organ failure, and higher rates of mortality [Citation6]. Further, patients with LPLD may be at enhanced risk of pancreatitis compared to patients with moderately high TG (~440–800 mg/dL), and certainly in comparison with patients with normal TG levels. According to one study, in comparison with patients with normal TG levels, patients with LPLD with TG > 800 mg/dL had a 360-fold greater risk of acute pancreatitis, and a greater risk compared to patients with TG values of ~440–800 mg/dL, underscoring the need to reduce TG in this population [Citation7]. Long-term complications of FCS as a result of acute pancreatitis may include chronic pancreatitis, pancreatogenic (Type 3c) diabetes, and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, with their attendant complications.

Quality of life (QoL) is compromised in patients with rare diseases. A recent study in patients with FCS (N = 166) documented the significant burden of illness and reduced QoL [Citation3]. Patients with FCS reported cognitive and emotional symptoms such as difficulty concentrating (16%), impaired judgment (11%), anxiety/fear/worry about pain or an attack of acute pancreatitis (34%), their health (26%), food (20%), and feeling out of control or helpless due to FCS (17%). These symptoms were experienced daily to monthly [Citation3], many with a high magnitude of severity. FCS also had substantial impact on the patients’ professional lives with only 23% reporting current full-time employment [Citation3]. Forty percent of patients with FCS reported being unemployed and a majority (94%) of unemployed or part-time employed patients with FCS attributed their employment status to the disease [Citation3].

In addition to the significant burden of illness of FCS due to the symptom profile, patients also face a challenging path to diagnosis that included seeing multiple health-care specialists (an average of 5) prior to receiving a diagnosis [Citation3]. Even though FCS can be diagnosed clinically, many health-care providers may not be familiar with the disease which adds to the challenge. However, a diagnosis of FCS may only provide limited relief as there is currently no approved treatment option. Currently, TG levels in patients are managed by following an extremely restrictive very low-fat diet (≤ 15–20 g of fat daily) [Citation8]. Patients report this diet is challenging to adhere to and requires much of their time and energy to maintain [Citation3]. Despite rigorous adherence to the diet, fasting TG can remain above the threshold for the risk of acute pancreatitis [Citation5]. Fifty-three percent of patients report still experiencing symptoms suggesting diet alone is not effective in controlling many of the symptoms of FCS [Citation3].

Being connected to peer support groups has been shown to positively impact patients with breast cancer [Citation9] and HIV [Citation10]. In lieu of treatment options for patients with FCS, connecting to other patients can provide the means to improve their QoL. In rare diseases, deficits in QoL are common [Citation11] including feelings of isolation and anxiety. Indeed, a case report of a patient with FCS demonstrates that attending a single FCS-support group meeting reduced his disease-related anxiety and stress. The patient also reported feeling more empowered about his ability to manage FCS [Citation12].

Based on the experience of patients with other diseases, and the FCS-specific case study, we hypothesized that connection of patients with FCS to disease specific communities or websites could have a positive impact on their QoL and improve their ability to manage their disease. The CONNECT study examined how connection to these resources impacted patients’ QoL using a retrospective patient-reported, web-based survey as a tool.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Defining social connections

Connectedness was categorized based on previous studies [Citation13,Citation14]. Patients in this study were grouped based on their connectedness in one of three categories. Patients categorized as actively connected regularly take part in ongoing conversations with members of the websites or groups (i.e. at least once every 2 weeks). Patients categorized as passively connected have joined, followed, or read a forum or channel, but will less frequently actively take part in any ongoing conversations (i.e. less often than once every 2 weeks, or never take part in ongoing conversations). Non-connected patients were never connected to FCS websites or groups.

2.2. Survey design and testing

A customized 30-minute web-based retrospective survey was designed [Citation14] to reflect the level of social involvement of patients with FCS. A beta-test version of the survey was used to conduct cognitive interviews among four patients with FCS. These interviews identified potential sources of response error in the survey. Responses from these patients and an external physician were incorporated into the final version of the survey and constituted the evaluable data.

2.3. Sample and data collection

Data were collected from patients with FCS and caregivers (N = 50), who responded on behalf of the patient with FCS, from 2 countries (United States, Canada). Participants were identified as having FCS or caring for patients who have FCS if they indicated the patient had one or more of the following: familial LPLD, FCS, Fredrickson’s type 1 hyperlipoproteinemia, high TG levels with a history of pancreatitis, or high TG levels with a history of severe abdominal pain that required hospitalization not due to a readily identifiable cause.

Data were collected anonymously via an online survey link between December 2017 and February 2018.

Participants were found through health-care professionals who treat patients with FCS, as well as FCS patient support groups and institutions. Potential participants were directed to the survey via a flyer, which informed them about the study. The flyer was also posted on community FCS Facebook pages by patient moderators. Patients who had previously attended patient advisory boards also received the flyer via email.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and ethics committees in the participating countries or institutions.

2.4. Measures

A detailed description of each respondent and caregiver’s engagement with FCS-specific resources was obtained to determine the level of connectedness. Analysis of engagement included the type of connection (in-person, online, etc.), level of identification/association with each FCS-related group, frequency of contact, time spent with each FCS-related group, and the duration of connection. Connectedness was measured by asking about ways of being connected, the time spent on each means of connection, the length of time of connection, and the association with each related group [Citation14]. The impact of connectedness was assessed based on similar methodologies in other studies with questions about overall health, level of anxiety and depression, social isolation, relationship with disease state, self-worth [Citation15], relationship with family and colleagues, impact on work productivity, and overall FCS symptom severity. FCS symptom severity was measured on a 7-point Likert-like scale with 1 − extremely mild, 2 − very mild, 3 − mild, 4 − moderate, 5 − slightly severe, 6 − severe, and 7 − extremely severe. QoL changes were measured before and after ‘being connected’ for actively and passively connected respondents while non-connected respondents were solely asked about their current QoL.

2.5. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 (Armonk, NY). Sample characteristics, including the level of connectedness, were assessed by calculating means for continuous variables, and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Responses obtained before being connected to a FCS-specific website or group were compared to those after being connected using paired t-tests for continuous variables, and Wilcoxon signed rank tests for categorical variables. Differences between respondents who were actively involved with FCS-specific groups and those who were passively involved were tested using t-tests for continuous variables and z-tests for categorical variables. The Bonferroni correction was applied to control for multiple comparisons. A p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3. Results

Any level of connection provided positive benefits in multiple areas of respondents’ lives. Respondents reporting a higher level of connection resulted in greater improvements in the areas assessed with the actively connected respondents experiencing the greatest benefits.

3.1. Respondents demographics

Key demographic information for the 50 respondents that completed the survey are found in . Of note, the majority of respondents were actively connected (56%, n = 28), 28% (n = 14) were passively connected, and 16% (n = 8) non-connected. Connected patients, both actively and passively, were also younger and began experiencing symptoms related to their FCS at an earlier age which corresponded to an earlier age of diagnosis.

Table 1. Respondent demographics and characteristics.

3.2. Overall health

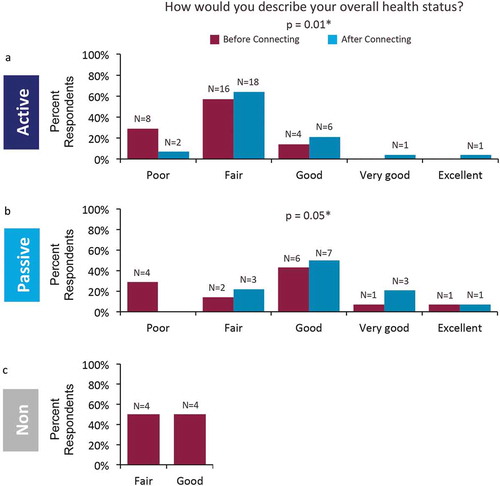

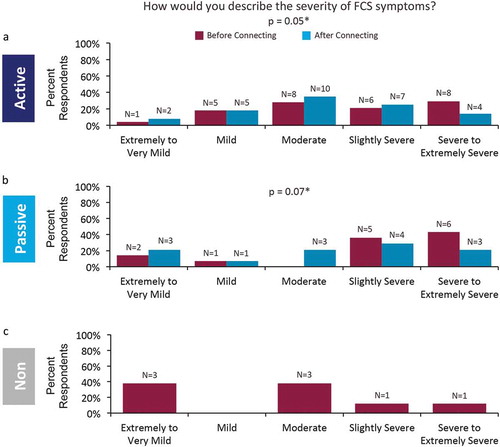

Connected respondents reported a significant (p = 0.01) increase in the perception of their overall health (). After connection, there was a 107% increase in actively connected respondents reporting good to excellent level of overall health. Passively connected respondents also reported a significant increase in perceived level of overall health. After connection, respondents reporting an overall health level of good, very good, or excellent increased by 37% (p ≤ 0.05). Non-connected respondents’ perception of their current health paralleled pre-connection values reported by connected respondents, with no respondent reporting very good or excellent health and 50% (n = 4) each reporting good or fair. Respondents also reported reduced perception of symptom severity after connecting (). Non-connected respondents reported a lower level of symptom severity compared to connected respondents, prior to connecting, despite having very similar perceptions of their overall health.

Figure 1. Impact of connecting on overall health perception. Respondents reported perception of their overall health before and after connecting for (a) actively connected and (b) passively connected respondents. (c) Non-connected respondents reported only their current perception of overall health. *p values are based on comparison of mean rating of 5-point Likert-like scale before and after connecting.

Figure 2. Impact of connecting on perception of FCS symptom severity. Respondents reported severity of FCS symptoms before and after connecting in (a) actively connected and (b) passively connected respondents. (c) Non-connected respondents reported their current level of symptom severity. *p values are based on comparison of mean rating of 5-point Likert-like scale before and after connecting.

3.3. Disease management

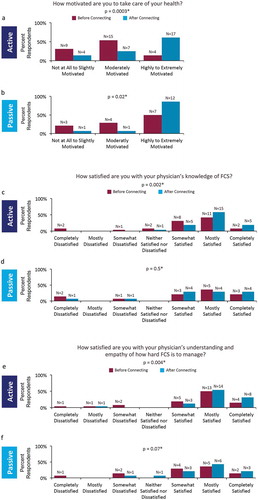

Respondents were more motivated to manage their disease, and take care of their health, after being connected (, ). Actively connected respondents who reported being highly to extremely motivated to take care of their health increased (p = 0.0003) over 3 times, from 14% (n = 4) to 61% (n = 17), after connecting (). The trend was also observed in passively connected respondents, with highly to extremely motivated respondents increasing (p = 0.02) from 50% (n = 7) to 86% (n = 12) after connecting ().

Figure 3. Disease management. Respondents reported their motivation to take care of their own health before and after connecting in (a) actively connected and (b) passively connected respondents. Respondents also reported their satisfaction with their treating physician’s knowledge of FCS in (c) and (d) and empathy for how hard FCS is to manage in (e) and (f) before and after connecting in actively and passively connected respondents. Improvements in satisfaction were only significant in actively connected respondents. *p values are based on comparison of mean rating of 7-point Likert-like scale before and after connecting.

Connecting to FCS-specific groups improved not only respondents’ personal motivation to manage their disease but also their satisfaction with their primary treating physician. Actively connected respondents reported significant improvements in their satisfaction with their treating physicians’ knowledge (p = 0.002) and their empathy toward the difficultly of managing FCS (p = 0.004) (, ). The percentage of respondents that reported being completely satisfied, after connecting, with both their physicians’ knowledge of and empathy toward FCS more than doubled for actively connected respondents from 8% (n = 2) to 19% (n = 5) and 15% (n = 4) to 31% (n = 8), respectively. Passively connected respondents saw a similar trend with a mean percent increase in satisfaction, but the increases were not statistically significant (, ).

3.4. Mental and emotional well-being

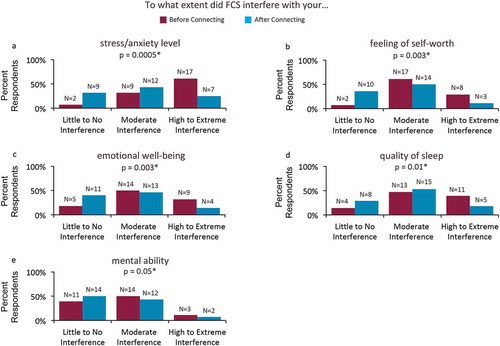

In addition to the improved perception of the physical manifestations of FCS, respondents also reported improvements in their mental and emotional well-being through connecting with FCS-specific resources. Actively connected respondents reported significant reductions in the interference of FCS in all queried categories including stress/anxiety levels, feeling of self-worth, emotional well-being, quality of sleep, and mental ability (). Stress/anxiety level had the greatest reduction in FCS interference factors after connecting; the number of respondents reporting high to extreme interference due to stress/anxiety reduced by 36% (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4. Mental and emotional well being of actively connected respondents. Respondents reported a significant reduction in the perceived interference of FCS in all listed categories of mental and emotional well-being after connecting. *p values are based on comparison of mean rating of 7-point Likert-like scale before and after connecting.

3.5. Social interaction

Being actively connected had positive impacts on respondents’ social activities and relationships (Supplementary Figure 2). Actively connected respondents reported significantly less interference of FCS on their ability to entertain in their homes, plan for activities, or socialize in general after connecting (Supplementary Figure 3). Actively connected respondents reported an increased network of individuals to discuss FCS with as well as reduced stress on their families. Passively connected respondents saw similar trends but improvements in these areas after connecting were not statistically significant (Supplementary Figure 4). Respondents did see significant benefits in one specific social relationship, with reported improvements in actively and passively connected respondents in their relationship with their spouse.

3.6. Barriers to connection

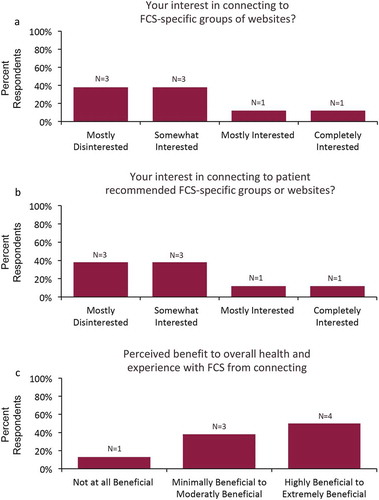

The level of interest of non-connected respondents (n = 8) for joining an FCS-specific website or group was quite low with only 26% (n = 2) of respondents reporting they were completely (13%, n = 1) or mostly (13%, n = 1) interested (). Reported interest levels were not increased even if a group was recommended by a fellow patient with FCS (). Despite this low level of interest, 50% (n = 4) of respondents reported they perceived it would be highly or very highly beneficial to join a FCS group (). Non-connected respondents reported multiple reasons for not connecting to FCS-specific groups. First, primary physicians did not recommend FCS-specific websites or groups to 88% (n = 7) of non-connected respondents. In these 7 patients, individual knowledge of FCS-specific resources was also a factor as 29% (n = 2) of non-connected respondents reported they were unaware of any of these resources. The platform for these resources, predominately social media and websites, was another barrier as 14% (n = 1) of respondents reported they do not use the requisite platform to engage in these groups.

Figure 5. Non-connected respondents interest in joining FCS-specific groups. Non-connected respondents reported (a) their interest in connecting to an FCS-specific website or group and (b) their interest if the group was recommended by another FCS patient. (c) Non-connected respondents were also asked the perceived benefit to their overall health and experience with FCS from connecting.

4. Discussion

The CONNECT study showed that connections to other FCS-related support groups improved the QoL of patients with this rare disease. Connected respondents experienced improvements in many areas of their lives including perceptions of overall health, mental and emotional well-being, and increased social interactions after connecting. In addition, being connected to other FCS patients increased participants’ motivation to take care of their own health. Any level of connection produced noticeable benefits, but active connection in the form of regular interaction with other patients reported the greatest improvements.

The results from the study are supported by similar reports in other rare and/or chronic diseases [Citation10,Citation16]. A recent case study described the positive impact of connection on disease-related anxiety and psychological distress experienced by a patient with FCS after attending a single FCS patient/caregiver support group meeting [Citation12]. The present study extends this report to a larger population of patients and provides an understanding of the impact of being connected to other patients with FCS.

Improved QoL in terms of significantly reduced stress/anxiety levels, improved feelings of self-worth, quality of sleep, emotional well-being, and mental ability was reported in actively connected patients with FCS. This study indicated that being connected to patient support groups was instrumental in making patients with FCS feel a sense of community and the participants reported improved social interactions, both within and outside the support groups.

Recommendations and referrals by physicians to specific support groups was the primary reason reported by many patients in this study as their motivation for joining patient support groups. In addition to improving their QoL, connecting FCS patients with one another affected the level of satisfaction with their primary treating physician. As the level of connectedness increased, patients with FCS had higher approval ratings of their primary treating physician’s knowledge of FCS and empathy toward the difficulty of managing FCS. The lack of effective treatment options and the improvements in QoL reported with connection to FCS-specific support groups combined with the above findings, lend support to physicians actively referring patients to support networks, potentially offering patients with FCS a promising strategy to help them lead healthier fuller lives. In this study, non-connected patients reported the primary barrier to connecting was the lack of referral to a specific group from a physician and lack of awareness of such resources. Since any level of connection led to perceived positive changes in areas of respondents’ lives, the allocation of additional time by physicians to encourage their patients to become actively connected with FCS support groups has the potential to yield more pronounced improvements.

The most common primary treating physicians in this study were lipidologists and pancreatologists. Other physician specialties known to diagnose FCS are endocrinologists, pediatricians [Citation3], and cardiologists [Citation17]. As FCS is a metabolic lipid disorder with gastrointestinal, nutritional, and psychological aspects, effective management of patients ideally comprises a multidisciplinary team. Any education designed for health-care professional should reach across multiple specialties and include recommendations to patient support groups such as the FCS Foundation (www.livingwithfcs.org; www.facebook.com/livingwithfcs), LPLD Alliance (www.lpldalliance.org), and Association de l’hyperchylomicroné (https://www.facebook.com/ahcmn/). Social connections in general have been linked to health behaviors [Citation18] including greater patient participation in health care [Citation10]. Motivating patients to adhere to lifestyle and dietary modifications remains a challenge for busy health-care professionals [Citation19,Citation20]. This current study showed that connecting to other patients with FCS reduced patients’ perceptions of symptom severity and motivated patients to manage their disease and take care of their health. Challenges in diagnosing FCS patients and the benefits of a timely diagnosis have been documented earlier [Citation3]. The results from this study potentially provide added motivations for physicians to diagnose and recommend connection to disease-specific support groups for patients with FCS, where they can get the psychosocial support they need to improve QoL and health outcomes.

Higher QoL is associated with higher levels of employment in patients with rare diseases [Citation11]. As reported earlier, patients with FCS have previously reported the disease to be a major contributor to their unemployed or underemployed status [Citation3,Citation17]. Only 28% of CONNECT respondents reported full-time employment aligning with previous reported values from a previous study of 23% [Citation3]. The CONNECT study did not show a trend between being connected and career choice of patients. Fifty percent of actively connected respondents reported strong to extreme interference of FCS on their career choice both before and after connecting. This is not surprising given the duration of connection reported in the study (approximately 18–22 months). It is likely that connection may have a more significant impact on the career choice of younger patients who would benefit from connecting earlier in their lives following a timely diagnosis.

The study was designed to be conducted online and inherent with such design was the challenge to recruit non-connected patients. Despite challenges, eight non-connected patients successfully completed the study. These patients reported experiencing less severe symptoms which they first experienced later in life. Perhaps these participants had milder cases of FCS and therefore were not concerned about being connected to other people with FCS or FCS-related resources. Nevertheless, the non-connected group indicated they believed they would benefit from being connected suggesting openness to join patient support groups with appropriate recommendations.

There were other limitations to this study. First, all data were retrospectively self-reported by patients and caregivers on behalf of patients, and the facts and experiences reported could not be independently verified. Second, this study was not longitudinal, and hence the evolution of symptoms over time and with experience of the disease could not be evaluated. Third, the sample sizes of the subgroups were low, with the non-connected subgroup having the smallest number of participants (n = 8). Nevertheless, we believe the data collected are representative of the FCS population. Lastly, participants were recruited through health-care professionals and patient support groups and institutions contributing to a possible selection bias.

Being connected to other patients with FCS did not change the long-term disease outlook of participants, who stated they continued to worry that their FCS would worsen as they aged. Despite the benefits seen with being actively connected patients, the serious, potentially life-threatening consequences of FCS highlight the critical need for treatment options for patients with FCS.

Our data support the current literature which shows social relationships have a positive impact on health [Citation21–Citation23] and QoL [Citation9]. Connecting patients with FCS through disease-specific resources expands their network of support and allows them to share their experiences. Patients and their families feel a sense of belonging and support and a reduced level of stress through connection with the larger FCS community. As one patient said ‘this group allows me a voice and freedom to know it’s not just me, I’m not alone. This has incentivized me to take an active role in my health again.’

5. Conclusions

FCS is a rare debilitating disorder that is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed. Even with strict adherence as the only available management option to an extremely restrictive very low-fat diet, patients continue to experience symptoms and feel socially isolated and report a decreased QoL. This study examined the impact of FCS-specific patient support resources on the QoL of patients with FCS. The results demonstrated that connecting patients with FCS to FCS-specific support groups and resources improved the QoL of patients in several areas, including health and motivation to take care of health, mental and emotional well-being, and physician satisfaction. As no treatment is currently available, the benefits in QoL reported with connection provide a valid reason for physicians to diagnose patients with FCS and all health-care professionals to connect these patients and their families to FCS-related groups to improve patient care and outcomes for both patients and their families.

Declaration of interest

V Salvatore, A Gilstrap, KR Williams, B Hubbard, S Thorat, M Stevenson and A Hsieh are employees of Akcea Therapeutics, Inc. AR Gwosdow received compensation for writing services by Akcea Therapeutics Inc. D Davidson is on the Speaker’s Bureau for Akcea Therapeutics, Inc., Amgen, Sanofi, Regeneron; and a consultant for Akcea Therapeutics, Inc. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

Reviewer Disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial relationships or otherwise to disclose.

CONNECT_manuscript_supplementary_figure_4.tif

Download TIFF Image (2.2 MB)CONNECT_manuscript_supplementary_figure_3.tif

Download TIFF Image (2.1 MB)CONNECT_manuscript_supplementary_figure_2.tif

Download TIFF Image (1.8 MB)CONNECT_manuscript_supplementary_figure_1.tif

Download TIFF Image (1.2 MB)Acknowledgments

First and foremost, the authors acknowledge and thank the patients and caregivers who participated in this survey. The authors would like to thank Trinity Partners, LLC for assistance with the survey design, data collection and interpretation. Authors would also like to thank Molly Harper, Francois Denis, Nelly Komari, and Stefan Zeitler for their thoughtful comments and guidance.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for the article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Brahm AJ, Hegele RA. Chylomicronaemia–current diagnosis and future therapies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015 Jun;11(6):352–362. PubMed PMID: 25732519.

- Burnett JR, Hooper AJ, Hegele RA. Familial lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Seattle: University of Washington. 2017 June 22.

- Davidson M, Stevenson M, Hsieh A, et al. The burden of familial chylomicronemia syndrome: results from the global IN-FOCUS study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018 Apr 26. DOI:10.1016/j.jacl.2018.04.009. PubMed PMID: 29784572.

- Gaudet D, Blom D, Bruckert E, et al. Acute pancreatitis is highly prevalent and complications can be fatal in patients with familial chylomicronemia: results from a survey of lipidologist. J Clin Lipidol. 2016;10(3):680–681.

- Blom DJ, O’Dea L, Digenio A, et al. Characterizing familial chylomicronemia syndrome: baseline data of the APPROACH study. J Clin Lipidol. 2018. DOI:10.1016/j.jacl.2018.05.013.

- Nawaz H, Koutroumpakis E, Easler J, et al. Elevated serum triglycerides are independently associated with persistent organ failure in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015 Oct;110(10):1497–1503. PubMed PMID: 26323188.

- Gaudet D, De Wal J, Tremblay K, et al. Review of the clinical development of alipogene tiparvovec gene therapy for lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Atherosclerosis Supplements. 2010 Jun;11(1):55–60. PubMed PMID: 20427244; eng.

- Williams L, Rhodes KS, Karmally W, et al. Familial chylomicronemia syndrome: bringing to life dietary recommendations throughout the life span. J Clin Lipidol. 2018 Apr 27. DOI:10.1016/j.jacl.2018.04.010. PubMed PMID: 29804909.

- Tehrani AM, Farajzadegan Z, Rajabi FM, et al. Belonging to a peer support group enhance the quality of life and adherence rate in patients affected by breast cancer: A non-randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal Research Medical Sciences: Official Journal Isfahan University Medical Sciences. 2011 May;16(5):658–665. PubMed PMID: 22091289; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3214378. eng

- Monroe A, Nakigozi G, Ddaaki W, et al. Qualitative insights into implementation, processes, and outcomes of a randomized trial on peer support and HIV care engagement in Rakai, Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2017 Jan 10;17(1):54. PubMed PMID: 28068935; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5223463.

- Bogart KR, Irvin VL. Health-related quality of life among adults with diverse rare disorders. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017 Dec 7;12(1):177. PubMed PMID: 29212508; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5719717.

- Wilson LM, Cross RR, Duell PB. Reduced psychological distress in familial chylomicronemia syndrome after patient support group intervention. J Clin Lipidol. 2018 Jan-Feb;12(1):240–242. PubMed PMID: 29195809.

- Cruwys T, Alexander Haslam S, Dingle GA, et al. Feeling connected again: interventions that increase social identification reduce depression symptoms in community and clinical settings. J Affect Disord. 2014 Apr;159:139–146. PubMed PMID: 24679402.

- Doosje B, Ellemers N, Spears R. Perceived intragroup variability as a function of group status and identification. J Exp Soc Psychol. 1995;31(5):410–436.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton university press; 1965.

- Doyle M. Peer support and mentorship in a US rare disease community: findings from the cystinosis in emerging adulthood study. Patient. 2015 Feb;8(1):65–73. . PubMed PMID: 25231828.

- Davidson M, Stevenson M, Hsieh A, et al. The burden of familial chylomicronemia syndrome: interim results from the IN-FOCUS study. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2017 May;15(5):415–423. PubMed PMID: 28338353.

- Lauder W, Mummery K, Jones M, et al. A comparison of health behaviours in lonely and non-lonely populations. Psychol Health Med. 2006 May;11(2):233–245. PubMed PMID: 17129911.

- Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, et al. Patient self-management of chronic disease in primary care. Jama. 2002 Nov 20;288(19):2469–2475. PubMed PMID: 12435261; eng.

- Funnell M, Anderson R. Empowerment and self-management of diabetes. Clinical Diabetes. 2004; 22(3):123-127.

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010 Jul 27;7(7):e1000316. PubMed PMID: 20668659; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2910600. eng.

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science (New York, NY). 1988 Jul 29;241(4865):540–545. PubMed PMID: 3399889; eng.

- Rico-Uribe LA, Caballero FF, Olaya B, et al. Loneliness, social networks, and health: a cross-sectional study in three countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0145264. PubMed PMID: 26761205; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4711964