Abstract

Introduction

Numerous studies have explored the interaction between physical activity (PA) and sleep quality illustrating the effect of physical exercise on sleep, yet previous researches have not investigated the relationship between physical exercise intensity and sleep quality.

Aim

This systematic review aims to examine the effect PA intensity on sleep quality in healthy populations.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review by searching latest 8 years publications. PubMed and Scopus were used to identify eligible studies with the searching terms, ‘sleep quality’ AND ‘physical activity’, within the timeframe between January 2010 and June 2018. All the included articles were systematically reviewed and analysed. The comparison of physical intensity and sleep quality was conducted based on the threshold of moderate PA and vigorous PA.

Results

Fourteen studies were included in the review. Analyses revealed that moderate PA seems to be more effective than vigorous activity in improving sleep quality. Furthermore, moderate physical exercise is beneficial to sleep quality in both young and old populations.

Conclusions

Moderate exercise showed more promising outcome on sleep quality than vigorous exercise. Future studies are suggested to elaborate detailed exercise suggestions by considering age groups in order to make accurate recommendations for health promotion.

Introduction

Sleep quality has a critical role in promoting health since researches over the past decade has documented that sleep disturbance has a powerful influence on the risk of medical illnesses including cardiovascular disease and cancer, and the incidence of depression [Citation1]. Even though the term ‘sleep quality’ has been commonly used in sleep medicine, the term ‘sleep quality’ has not been clearly defined. The National Sleep Foundation (NSF) reported the key determinants (sleep latency, number of awakenings >5 minutes, wake after sleep onset and sleep efficiency) of quality sleep among healthy individuals without regarding sleep architecture or nap-related variables [Citation2]. Previous study demonstrated that the meaning of sleep quality among individuals with insomnia and normal sleepers was broadly similar by comparing between individuals with and without insomnia, given that poor sleep quality is a key feature of insomnia [Citation3]. Nevertheless, the NSF defined the key indicators of good sleep quality, which include: sleeping more time while in bed (at least 85% of the total time), falling asleep in 30 minutes or less, waking up no more than once per night and being awake for 20 minutes or less after initially falling asleep [Citation4].

It is essential to clearly understand the relationship PA has with sleep quality, accurate and detailed PA intensity classification. The intensity of physical activity (PA) is related to how hard our body works while doing that activity. In accordance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines, moderate activity is defined as below 3.0–6.0 exercise metabolic rates (METs) (3.5–7 kcal/min), and vigorous activity is defined as greater than 6.0 METs (more than 7 kcal/min) [Citation5]. To benefit health, CDC recommend a variety of moderate and vigorous intensity physical activities. Physical activity is considered an effective, non-pharmacological approach to improve sleep. In addition, physical exercise is recommended as an alternative or complementary approach to existing therapies for sleep problems [Citation6]. Evidence from cross-sectional studies indicated that physically active adolescents have more favourable sleep quality than those physically inactive [Citation7,Citation8]. A recent systematic review revealed that evening exercise may positively affect sleep, but vigorous exercise might impair sleep-onset latency, total sleep time [Citation9]. The relationship between PA intensity (i.e. moderate exercise, vigorous exercise) and sleep quality needs to be specified even though the benefits of physical exercise and sleep quality has been highly regarded.

According to present knowledge, good sleep quality is fundamental to wellbeing and known to be influenced by biological factors and lifestyle. The benefits of physical exercise have been examined from both biological and physiological perspective. However, the prevalence of sleep loss is increasing nowadays [Citation10]. Insufficient sleep and irregular sleep–wake patterns documented in younger adolescents, presented alarming in college population [Citation11]. Impaired sleep quality is adversely associated with neurocognitive and academic performance [Citation12]. Poor sleep quality is negatively associated with academic performance in adolescents from middle school through the college years [Citation13]. Despite the biological necessity of sleep, it has been traded off in modern societies to accommodate social and work schedules. Additionally, sufficient sleep is important to personal achievements [Citation14].

It is generally thought that physical exercise constitutes a therapeutic behaviour which promotes sleep [Citation6,Citation15]. We now know that the quantity and/or quality of sleep is involved in the manifestation of various alterations in physical exercise functions. Leisure time physical exercise contributes to increased total energy expenditure [Citation16]. Moreover, it was demonstrated that activity can improve neuropsychological performance and subjective sleep quality in older adults [Citation17]. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep is considered a sensitive marker of the exercise effects on sleep. Exercise is significantly correlated with the decrease of REM sleep [Citation18], which explained the mechanism of PA effect on sleep.

Both vigorous and moderate activities may be beneficial to metabolic issue among middle-aged populations [Citation19]. The intensities of activity need to be taken into consideration when elaborating the relationship between PA and sleep quality. Low to moderate intensity Tai Chi program was demonstrated to be beneficial in improving self-rated sleep quality [Citation20]. It revealed that participating in an exercise training programme has positive effects on sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults [Citation6]. In this regards, this would indicate that physical exercise may elicits larger changes in sleep.

Given that age is likely an important mediating factor influencing the intensity of physical exercise, it is important to examine the incidental effect of age. The aging population is faced with a high prevalence of physical disability. It has been examined that poor physical function is associated with sleep fragmentation and hypoxia in older men [Citation21]. However, it was suggested that vigorous exercise is positively related to adolescents' sleep, in which the adolescents are athletes. The interaction of age in the functioning of physical intensities on sleep requests more exploration.

As reported, physical inactivity is prominent in the causal constellation for factors predisposing to cardiovascular disease [Citation22]. What kind of intensities of PA is recommended for the general population? It is consequential to address a common conclusion for general population. Thus, the aim of the present review is twofold. First, to reveal the association between PA intensity and sleep quality in general population. Second, to explore the interaction of age as a mediator of the exercise effects on sleep quality.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Two search engines, PubMed and Scopus, were used to identify studies for inclusion from January 2010 to June 2018. The two databases were search separately. In PubMed, we used the term ‘sleep quality’ AND ‘physical activity’ OR ‘sleep quality’ AND ‘exercise’ to search for the studies. Whereas, in Scopus, due to the searching box in Scopus is different from PubMed, we manually typed in our searching terms by selecting proper connections on the webpage. In both databases, only English articles were taken into consideration. Additionally, the available studies related to PA (e.g. Taichi, Baduanjin, etc.) with sleep quality were manually screened for any additional possibly relevant studies.

Study selection

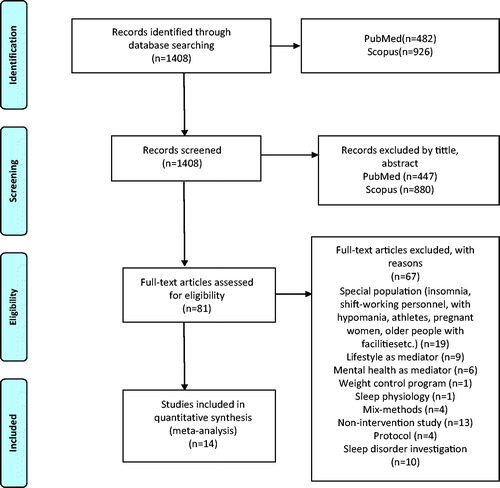

Articles from PubMed (n = 482) and Scopus (n = 926) online went into selection process. According to the search strategy, a total of 81 articles went through full-text check from 1408 retrieved records after titles and abstracts screening. Followed by careful full-text examination, 67 articles were excluded due to multiple reasons (listed in ).

The database search was conducted in one week in November 2018. With the search results listed on computer screen, the studies conducted with non-eligible participants were kicked out by screening the title and abstract. Those studies that were potentially relevant to the inclusion criteria were selected and waited for the second-round check. After screening by title and abstract, all selected studies from the two databases were pooled together for full-text check. Articles that retrieved on the basis of the tittle and abstract or when the decision could not be made based on the inapparent abstract, were gone through full-text assessment. After full-text check, studies have been included into the systematic review. The duplication check was performed manually within the eligible studies after full-text check. Mendeley (version: 1.19.2) was used to store and manage the included studies. The librarian helped with full-text access.

The PRISMA flow diagram [Citation23] was used to elaborate the study selection process.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) observational studies, including randomised control trial, longitudinal, cross-sectional, pre-post and case-control studies. (2) Participants were neither hospitalised patients, nor people with medical assistance (e.g. pregnant women, people with facilities, etc.). (3) Studies were not included if participants suffered with psychiatric disorders (e.g. hypomania, etc.). (4) Shift working personnel were also not included, since it has already disrupted. (5) Study protocols were excluded. (6) Studies illustrated non-relevant factors (e.g. mental health, life style) on sleep or taken sleep as risk factor. All the other studies were excluded if they could not meet the inclusion criteria.

Quality assessment

Incorporating with the study inclusion criteria that the current review is not only limited to RCTs, but also put eyes on other study designs (e.g. cross-over study, pre-post study, longitude study, etc.), we used the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool (MMAT-version 2011), which was developed for the quality appraisal of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods reviews [Citation24,Citation25]. The MMAT was designed for the appraisal stage of complex systematic literature reviews. There are five domains following with five scoring metrics individually, four items in each domain in qualitative, quantitative randomised controlled, quantitative non-randomised, quantitative descriptive studies, three items in the domain of mixed methods.

For each retained study, an overall quality score will be calculated by using the MMAT. The score can be presented using quartile descriptors. The questions in each domain in the appraisal are answered by ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘can’t tell’, since there are four questions in each domain (except mixed methods domain), the score varies from 1 (one criteria met) to 4 (all criteria met). For qualitative and quantitative studies, this final score (score of quality) was calculated from the number of criteria met. For mixed methods research studies, the overall quality score takes the lowest score of the study components. For example, the score is 1 when QUAL = 1 or QUAN = 1 or MM = 0; it is 2 when QUAL = 2 or QUAN = 2 or MM = 1; it is 3 when QUAL = 3 or QUAN = 3 or MM = 2; and it is 4 when QUAL = 4 and QUAN = 4 and MM = 3 (QUAL being the score of the qualitative component; QUAN the score of the quantitative component; and MM the score of the mixed methods component) [Citation24].

The questions in each domain were coded by Q1–Q4 based on the sequence from the original scale. We code 1 if the answer is ‘yes’, 0 if the answer is ‘no’, and CT if the answer is ‘cannot tell’. A summary of the number of ‘yes’ was made to show the proportion of study quality in different strata.

Data extraction

We redefined the study by the following standards: (1) is the study a randomised control trial? (2) Did the study use PSQI as the measurement for sleep quality? (3) Are there complete outcome data? (4) Are the samples properly selected? (5) Are there case and control groups? These questions were taken as risk factors when investigating the relationship between PA and sleep quality.

Results and discussion

Summary of the studies

Finally, 14 studies including RCTs and non-RCTs were included in the systematic review. The extracted standardised headings include: authors, publication years, number of participants, age range, interventions, study design, measures for sleep, and results (). The intervention duration of the included studies ranges from 35 minutes to 24 weeks conducted in vigorous physical exercise and moderate exercise among different age groups. Moderate physical exercise was more frequently launched (e.g. walking, Tai chi, daily home exercise, Pilates, etc.). Half of the participants were young adults (18–45 years old), 36% of the participants were elderly people above 45 years old, while 14% of the participants were under 18 years old. Most of the studies showed positive results toward global sleep score by PSQI. The two studies that worked on vigorous PA demonstrated that vigorous physical exercise does not affect sleep quality, of which the two studies were qualitative and cross-sectional study.

Table 1. The details of included studies.

Quality appraisal

The quality appraisal presents three quantitative descriptive study (cross-sectional studies) and one qualitative study. Ten articles were experimental studies organised either RCT or non-RCT. The non-RCT studies were all pre-post studies except one prospective study. The result of quality assessment is listed in . In the selected studies, only ‘quantitative non-randomized control trail’, ‘quantitative randomized control trail’, ‘quantitative descriptive’ and ‘qualitative’ study domains were found. In total, 43% of the included articles met three criteria. The number of studies identified by meeting four criteria (29%) was slightly higher than the number of studies met two criteria (21%). Only 7% study (n = 1) met only one criteria.

Table 2. The quality assessment of selected articles.

Positive results of moderate exercise

Physical activity was popular in scientific research in promoting health conditions. Sleep quality and sleep health draw a lot of attention among health professions and researchers. The trials of physical exercise on sleep quality were diverse. But, more positive results received from previous studies despite the types and dedicated samples. Physical exercise is supposed to benefit sleep quality in a wide spectrum of exercise types. An increase of walking distance by 500 steps per week showed positive effect in improving sleep quality on menopausal women [Citation33]. Not only in menopausal women, but also in secondary school students, walking exercise showed significant improvement of subjective sleep quality [Citation31]. Moreover, in a real-world study added additional evidence that daily walking exercise is beneficial to improve subjective sleep quality in people both physically active and non-active [Citation28]. Aerobic exercises, such as Tai Chi and home exercise, were examined within community-dwelling elderly in a randomised controlled trial, and exercisers reported better sleep quality than non-exercisers [Citation26,Citation27,Citation32]. Rather than slow movement exercise, participation of moderate-intensity physical activities (e.g. included roller skating, bicycling, baseball and walking/running) launched in college students (nine exercisers and 10 non-exercisers), indicated that participation in such a programme improves sleep [Citation30]. Physical exercise may partially improve sleep components. As evidence showed that home-based 30-min Pilate’s exercises also showed significant improvement in subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, daytime dysfunction and global PSQI score, but not in sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency and sleep disturbance [Citation34]. Physical activity interventions that showed positive results were mostly moderate exercise or moderate to vigorous exercise. The implementation of physical exercise need to take into participants’ age and health status into consideration. Intensity and duration of PA for sleep benefits are under discussion.

Negative/novel results of moderate exercise

Even though more positive results were found in the included articles, negative or novel results are still existed. A floor-seated exercise programme conducted in 77 old participants (between 71 and 85 years old) found no significant effect on sleep quality [Citation36]. As illustrated from a cross-sectional study launched in low socioeconomic status urban area, decreased PA may be associated with poor sleep [Citation35,Citation37]. It was recommended that PA may be modifiable risk factors to improve sleep [Citation35].

Vigorous exercise and sleep quality

In a cross-sectional study, covered participants from 23 countries, it was demonstrated that there was no association between vigorous PA and sleep quality and quantity [Citation38]. A qualitative study examined the effects of acute exercise on sleep; however, it found no effect of vigorous PA on sleep quality [Citation29]. Nevertheless, there were findings that did not support the result. Among people with insomnia, acute morning exercise turned out to improve nocturnal sleep quality in individuals with difficulty initiating sleep [Citation39]. In addition, it was indicated that increased PA is favourably associated with restoring sleep and vigorous PA levels tend to be a better predictor for good sleep than moderate PA [Citation40]. To our best acknowledgement, the number of studies defining the effect of vigorous PA on sleep quality is limited.

Analysis of physical activity and sleep quality

Moderate physical activities were more popular in scientific research as physiotherapy method to improve sleep quality. It is a good idea to discuss the effects of physical intensity and duration on sleep quality. A cross-sectional study showed that neither intensity, nor duration of PA was associated with sleep quality or quantity [Citation41]. It was highly suggested that regular moderate-intensity exercise programme improves self-rated sleep quality in older adults with moderate sleep complaints [Citation42]. According to the results illustrated above, it is reasonable to assume that physical intensity may be related to sleep quality, which still needs more evidence [Citation43].

Sleepiness was suggested to associated with age in daytime workers [Citation44]. Age, as a moderator of PA, did not show enough clue moderating the relationship between PA and sleep quality in this review.

Risk of bias

The examination of home exercise on sleep quality and daytime sleepiness of elderly people consisted 88% females [Citation28], in which a gender bias may not be avoided. Gender difference in motivation of physical exercise is dominant in sports participation [Citation45]. In the case control study, a 12-week physical activities programme on sleep [Citation30], involved 19 participants (10 participants in intervention group, nine participants in control group), the sample size is small to receive confidential results, which could lead to a potential risk to bias the extracted results. In the cross-sectional study, which analysed the vigorous PA, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low- and middle-income countries, it may be helpful to take regional difference in sleep habits into consideration.

Limitations

Although all of the studies were strictly selected by the inclusion criteria, limitations exist. First, the classification of physical activity levels are poorly defined and not specify explained in scientific research. We classified the term ‘moderate physical activity’ and ‘vigorous physical activity’ figuring out the exercise examples from the CDC recommendations. Second, obesity was indicated as moderate factor between PA and sleep quality [Citation46]. In this review, bodyweight of the participants was not taken into consideration. In the study selection, we only considered the English language articles, which technically narrowed down the selection scope.

Conclusions

From the present review, the relationship between physical intensity and sleep quality is lack of experimental evidence. The aspects discussed in this review were important in improving sleep quality. In addition, no exhaustive data were available about the possible age factors in interacting between PA and sleep quality. There were ambiguous data illustrating the effect of acute exercise on sleep and sleep disorders [Citation39,Citation47]. Little evidence supports the vigorous PA benefit sleep quality. Cultural and religious beliefs may influence beliefs of sleep since it was predicted that spiritual and religious activity associate with different components of sleep quality [Citation48]. This review demonstrates that moderate physical exercise benefits sleep quality in all age groups in healthy population, given that physical intensity is well acknowledged. However, the data available do not really support the gender interaction when conducting physical exercise. There were few scientific data addressed how physical exercise duration is sufficient in terms of moderate activity, which was a specific aspect has not yet been explicitly investigated in scientific research. Physical exercise is subjective and individual, in this context, people are free to carry out any kinds of activities. Qualitative recommendations, guidelines are essential.

The present study demonstrated that moderate PA is impactful in sleep quality; however, specified suggestions of structured physical exercise types are lack of experimental verification. Future studies are suggested to clarify the proper amount of moderate physical exercise in improving sleep quality and elaborate the relationship between physical intensity and sleep quality. Further studies also suggested to explore detailed exercise suggestions by considering different age groups in order to make accurate evidence-based recommendations for health promotion.

| Abbreviations | ||

| NSF | = | National Sleep Foundation |

| PA | = | Physical Activity |

| CDC | = | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |

| ACSM | = | American College of Sports Medicine |

| METs | = | Metabolic rates |

| REM | = | Rapid Eye Movement |

| PRISMA | = | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RCTs | = | Randomized Control Trials |

| MMAT | = | Mixed Method Appraisal Tool |

| QUAL | = | Qualitative |

| QUAN | = | Quantitative |

| MM | = | Mixed Methods |

| PSQI | = | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Irwin MR. Why sleep is important for health: a psychoneuroimmunology perspective. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:143–172.

- Ohayon M, Wickwire EM, Hirshkowitz M, et al. National Sleep Foundation's sleep quality recommendations: first report. Sleep Health. 2017;3:6–19.

- Harvey AG, Stinson K, Whitaker KL, et al. The subjective meaning of sleep quality: a comparison of individuals with and without insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:383–393.

- National Sleep Foundation. What is good quality sleep? [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/press-release/what-good-quality-sleep

- CDC. General physical activities definition by level of intensity. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/pdf/PA_Intensity_table_2_1.pdf

- Yang PY, Ho KH, Chen HC, et al. Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2012;58:157–163.

- Park S. Associations of physical activity with sleep satisfaction, perceived stress, and problematic Internet use in Korean adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1143.

- King A, Pruitt L, Woo S, et al. Effects of moderate-intensity exercise on polysomnographic and subjective sleep quality in older adults with mild to moderate sleep complaints. J Gerontol A: Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:997–1004.

- Stutz J, Eiholzer R, Spengler CM. Effects of evening exercise on sleep in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2018;49:1–19.

- Ferrie JE, Kumari M, Salo P, et al. Sleep epidemiology—a rapidly growing field. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40:1431–1437.

- Lund H, Reider B, Whiting A, et al. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46:124–132.

- Curcio G, Ferrara M, Degennaro L. Sleep loss, learning capacity and academic performance. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:323–337.

- Wolfson A, Carskadon M. Understanding adolescent's sleep patterns and school performance: a critical appraisal. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:491–506.

- Ahrberg K, Dresler M, Niedermaier S, et al. The interaction between sleep quality and academic performance. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:1618–1622.

- Youngstedt SD. Effects of exercise on sleep. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:355–365.

- Tremblay MS, Esliger DW, Tremblay A, et al. Incidental movement, lifestyle-embedded activity and sleep: new frontiers in physical activity assessment. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32:S208–S217.

- Benloucif S, Orbeta L, Ortiz R, et al. Morning or evening activity improves neuropsychological performance and subjective sleep quality in older adults. Sleep. 2004;27:1542–1551.

- Oda S, Shirakawa K. Sleep onset is disrupted following pre-sleep exercise that causes large physiological excitement at bedtime. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:1789–1799.

- Rennie K, McCarthy N, Yazdgerdi S, et al. Association of the metabolic syndrome with both vigorous and moderate physical activity. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:600–606.

- Li F, Fisher K, Harmer P, et al. Tai Chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:892–900.

- Dam T, Ewing S, Ancoli-Israel S, et al. Association between sleep and physical function in older men: the osteoporotic fractures in men sleep study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1665–1673.

- Kohl H. Physical activity and cardiovascular disease: evidence for a dose response. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:S472–S483.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012.

- Pluye P, Robert E, Cargo M, et al. Proposal: a mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews; 2011. [cited 2019 May 28]. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com

- Pace R, Pluye P, Bartlett G, et al. Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49:47–53.

- Nguyen M, Kruse A. A randomized controlled trial of Tai chi for balance, sleep quality and cognitive performance in elderly Vietnamese. Clin Interv Aging. 2012;7:185–190.

- Brandao G, Callou A, Brandão G, et al. The effect of home-based exercise in sleep quality and excessive daytime sleepiness in elderly people: a protocol of randomized controlled clinical trial. Man Ther Posturol Rehabil J. 2018;16. http://dx.doi.org/10.17784/mtprehabjournal.2018.16.577.

- Hori H, Ikenouchi-Sugita A, Yoshimura R, et al. Does subjective sleep quality improve by a walking intervention? A real-world study in a Japanese workplace. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011055.

- Myllymaki T, Kyrolainen H, Savolainen K, et al. Effects of vigorous late-night exercise on sleep quality and cardiac autonomic activity. J Sleep Res. 2011;20:146–153.

- Hurdiel R, Watier T, Honn K, et al. Effects of a 12-week physical activities programme on sleep in female university students. Res Sports Med. 2017;25:191–196.

- Baldursdottir B, Taehtinen R, Sigfusdottir I, et al. Impact of a physical activity intervention on adolescents’ subjective sleep quality: a pilot study. Glob Health Promot. 2017;24:14–22.

- Kashefi Z, Mirzaei B, Shabani R. The effects of eight weeks selected aerobic exercises on sleep quality of middle-aged non-athlete females. Iran Red Cresc Med J. 2014;16:e16408.

- Najafabadi M, Farshadbakht F, Abedi P. Impact of pedometer-based walking on menopausal women's sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Maturitas. 2017;19:100–196.

- Ashrafinia F, Mirmohammadali M, Rajabi H, et al. The effects of Pilates exercise on sleep quality in postpartum women. J Bodyw Move Ther. 2014;18:190–199.

- Greever C, Ahmadi M, Sirard J, et al. Associations among physical activity, screen time, and sleep in low socioeconomic status urban girls. Prev Med Rep. 2017;5:275–278.

- Choi M, Sohng K. The effects of floor-seated exercise program on physical fitness, depression, and sleep in older adults: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Gerontol. 2018;12:116–121.

- Wu X, Tao S, Zhang Y, et al. Low physical activity and high screen time can increase the risks of mental health problems and poor sleep quality among Chinese college students. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0119607.

- Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Vigorous physical activity, perceived stress, sleep and mental health among university students from 23 low- and middle-income countries. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017. [Epub ahead of print]

- Morita Y, Sasai-Sakuma T, Inoue Y. Effects of acute morning and evening exercise on subjective and objective sleep quality in older individuals with insomnia. Sleep Med. 2017;34:200–208.

- Lang C, Brand S, Feldmeth AK, et al. Increased self-reported and objectively assessed physical activity predict sleep quality among adolescents. Physiol Behav. 2013;120:46–53.

- Kakinami L, O'Loughlin E, Brunet J, et al. Associations between physical activity and sedentary behavior with sleep quality and quantity in young adults. Sleep Health. 2017;3:56–61.

- King AC, Oman RF, Brassington GS, et al. Moderate-intensity exercise and self-rated quality of sleep in older adults. JAMA. 1997;277:32.

- Kredlow M, Capozzoli M, Hearon B, et al. The effects of physical activity on sleep: a meta-analytic review. J Behav Med. 2015;38:427–449.

- Åkerstedt T, Hallvig D, Kecklund G. Normative data on the diurnal pattern of the Karolinska Sleepiness Scale ratings and its relation to age, sex, work, stress, sleep quality and sickness absence/illness in a large sample of daytime workers. J Sleep Res. 2017;26:559–566.

- Kilpatrick M, Hebert E, Bartholomew J. College students' motivation for physical activity: differentiating men's and women's motives for sport participation and exercise. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54:87–94.

- Hargens TA, Kaleth AS, Edwards ES, et al. Association between sleep disorders, obesity, and exercise: a review. Nat Sci Sleep. 2013;5:27–35.

- Passos GS, Poyares D, Santana MG, et al. Effect of acute physical exercise on patients with chronic primary insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:270–275.

- Yang JY, Huang JW, Kao TW, et al. Impact of spiritual and religious activity on quality of sleep in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif. 2008;26:221–225.