Abstract

Aim

To compare the effectiveness of a biopsychosocial primary care intervention (Back on Track) with primary care physiotherapy as usual in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) experiencing low complex psychosocial complaints.

Method

A double-blind multicentre pilot-randomised controlled trial. Twenty-five patients (≥18 years) with non-specific CLBP (≥12 weeks) experience low psychosocial complaints and a low to moderate level of disability. The Back on Track intervention (four individual and eight group sessions) versus physiotherapy as usual (maximally 12 individual sessions). Primary outcome: functional disability (Quebec Back Pain Disability Score) at post-treatment and 3 months follow-up.

Secondary measures

Anxiety, depression, catastrophizing, pain intensity, kinesiophobia, self-efficacy, global perceived effect. Effects were analysed using linear mixed model analysis.

Results

No significant differences in functional disability were found between interventions at post-treatment (mean difference 0.10, 95% CI: −12.9 to 13.1) and 3 months follow-up (mean difference −5.4, 95% CI −19.1 to 8.3). Secondary outcomes also showed no significant differences.

Conclusions

No differences in effects were found between patients with CLBP experiencing low complex psychosocial complaints who receive the Back on Track intervention compared to patients receiving primary care physiotherapy as usual. Well-powered studies of sufficient methodological quality are needed to detect differences in effects.

Introduction

Back pain has the highest incidence rate of all health-related problems in the Netherlands [Citation1]. For low back pain (LBP) specifically, a lifetime prevalence of even up to 84% has been reported [Citation2,Citation3]. Therefore, LBP is considered as a common health problem. LBP can be classified as acute (<6 weeks of duration), subacute (6–12 weeks of duration) or chronic (CLBP, ≥12 weeks of duration). Although physical or biomedical factors are suggested to trigger the onset of LBP in the acute phase [Citation4], psychosocial factors have been found to influence the persistence of pain and disability [Citation5].

Due to the role of psychosocial factors, therapy recommendations for patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) are directed towards a biopsychosocial approach [Citation6]. The beneficial effects of therapies with a biopsychosocial approach in multidisciplinary care settings have been confirmed by several systematic reviews [Citation7–9]. A multidisciplinary intervention is however not indicated and needed for every patient with CLBP. In the Netherlands, e.g. only patients who experience moderate to complex psychosocial complaints and who are, due to these complaints, at least moderately disabled at functional level, are referred to a multidisciplinary intervention (often provided in a secondary or tertiary care setting) [Citation10]. Patients in which psychosocial complaints are present but influence daily life functioning to a lesser extent are referred to physiotherapy interventions in primary care. Physiotherapy interventions however include exercise therapy and manual therapy (i.e. manipulations and massage) [Citation11] and therefore not a specific biopsychosocial intervention.

To what extent a biopsychosocial approach would also be valuable in a primary care physiotherapy programme is inconclusive. To date, few studies investigated the differences in effects between a biopsychosocial primary care intervention and a (more biomedically oriented) physiotherapy programme, reporting mixed results [Citation11]. Some studies found significant beneficial effects in favour of the biopsychosocial intervention [Citation12,Citation13], while others reported no differences in effectiveness [Citation14,Citation15]. The varying findings could be a result of the selection procedure (patients not specifically selected on psychosocial complaints), the content of the intervention (different cognitive-behavioural elements used), physiotherapist’s competence and adherence to the biopsychosocial protocol (including amount of cognitive-behavioural training and support). For this reason, a new biopsychosocial primary care intervention ‘Back on Track’ has been developed based on existing multidisciplinary biopsychosocial interventions (secondary care) but specifically adapted to match the patient’s needs and the competence of trained physiotherapists in a primary care physiotherapy setting [Citation16].

The aim of this study was to compare the effects of the Back on Track intervention with primary care physiotherapy as usual. The research question for this study included: What is the difference in treatment effect (change in functional disability) between the Back on Track intervention and primary care physiotherapy as usual at post-treatment and 3 months post-treatment in a subgroup of patients with CLBP who experience psychosocial complaints that influences daily life functioning minimally?

Materials and methods

Design

This study is a pragmatic multicentre double-blind pilot Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) and is registered at ClinicaTrials.gov (NCT02220543). Ethical approval was provided by the Medical Ethics committee of the University Hospital of Maastricht and Maastricht University (METC azM/UM; METC143019). The study was monitored by the Clinical Trial Centre Maastricht (CTCM), the Netherlands. An extensive description of the study protocol has been published previously [Citation17].

The inclusion period lasted from August 2014 to May 2016. Recruitment was conducted by physicians specialised in pain rehabilitation, working at the Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC+), the Netherlands. In case patients indicated to be interested in study participation, patients were invited for an intake at Maastricht University (UM) where they received additional information regarding the study. They provided written consent to participate and agreed that previously collected questionnaires in daily care were used for this study (i.e. questionnaires completed prior to the consultation with the physician). In addition, patients completed baseline questionnaires at the intake session. Patients were centrally randomised to either the Back on Track intervention or primary care physiotherapy as usual using block randomisations via a computerised random number generator. The allocation sequence was accessible for the research assistant only and concealed for patients, physicians (recruiter), physiotherapists, researchers and data analysts. Researchers, data analysts, and patients remained blinded for treatment allocation. The research assistant, physiotherapists and physicians could not be blinded during treatment since they were involved in the intervention/logistics of the study.

Participants, therapists, centres

Adult patients (18–65 years) were eligible for inclusion if they had CLBP for ≥12 weeks, psychosocial were present but not complex, and functional disability was low to moderate. An upper age limit was included as we expected that patients over 65 years would have increased risk for comorbidity and may not be able to perform physical activities as intended during the treatment. The classification ‘low psychosocial complaints’ and ‘a low to moderate level of disability’ was based on the expert opinion of the referring physicians in rehabilitation medicine. To support the classification, physicians had the ability to use the outcome of questionnaires which patients completed prior to the consultation [i.e. Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS; range score ≥18–20), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; range score 8–11), RAND-36 item Health Survey (RAND-36; score >42), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS; score >4)]. Patients needed to speak and read Dutch sufficiently, and to be willing to receive a biopsychosocial treatment approach. Patients were excluded in case of specific CLBP (e.g. infection, tumour, osteoporosis, fracture, structural deformation, inflammatory process, radicular syndrome or cauda equina syndrome), pregnancy and/or suspicion of an (underlying) psychiatric disease.

Physiotherapy treatments were provided by physiotherapists working in primary care practices located in Maastricht, the Netherlands and the surrounding area. Four practices provided the Back on Track intervention, four practices primary care physiotherapy as usual. Practices were selected on appropriate facilities, willingness and motivation to participate. Each practice designated own physiotherapist(s) to provide the treatment. No specific criteria for physiotherapists were formulated, except that physiotherapists providing the Back on Track intervention should be motivated to provide a protocolled biopsychosocial oriented intervention and to receive a training programme.

Interventions

All patients received medical education from the referring physician prior to recruitment. This included information about pain physiology and the difference between acute and chronic pain. Physicians reassured that patients could improve the level of daily activities despite pain and explained that hurt would not equal harm.

Patients randomised to the Back on Track intervention received four individual sessions (30 minutes) and eight group sessions (60 minutes). The Back on Track intervention stimulated patients to gain insight in pain mechanisms, behaviour and beliefs, coping styles, goal-setting and self-management strategies. The intervention included elements of cognitive behavioural approaches such as Graded Activity and Exposure in vivo. Patients furthermore received a workbook with basic information about the treatment and homework assignments . A detailed description of the Back on Track intervention is described in detail elsewhere [Citation16]. Compliance threshold with the Back on Track intervention was reached if a patient attended at least three individual sessions and at least half of the group sessions. Although no literature is available to define an appropriate compliance threshold, we expected this combination of individual and group sessions to be sufficient to comprehend the discussed cognitive-behavioural topics and to apply them into practice. Physiotherapists received a manual with standardised treatment sessions prior to the start. Physiotherapists were trained to deliver the Back on Track intervention according to the protocol and to deliver cognitive behavioural elements (three meetings of 4 h). Two booster sessions were offered to physiotherapists during the study. Behavioural therapists and physiotherapists having more than 5 years of experience with cognitive-behavioural treatment for patients with CLBP offered the training and booster sessions.

Table 1. Content of the back on track intervention.

Patients randomised to primary care as usual received individual physiotherapy sessions according to physiotherapists’ best practice and the Dutch profession-specific guideline for LBP [Citation18]. The number of sessions was at the discretion of the physiotherapists, but to a maximum of twelve sessions to keep the length comparable to the Back on Track intervention. A log was kept regarding the content, frequency and duration of the therapy. Physiotherapists received no treatment manual or training for treatment delivery. Physiotherapists only received one meeting to be informed about the study logistics. They were not informed about the content of the Back on Track intervention to prevent cross-contamination.

Outcome measures

Patients completed questionnaires at baseline, directly post-treatment and at 3 months post-treatment. The primary outcome was functional disability using the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS, 0–100) [Citation19–21]. Secondary outcomes were: (1) pain intensity, measured with the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) ranging from 0 (no pain) to 10 (worst pain); (2) pain catastrophizing, measured with the PCS (0–52) [Citation22,Citation23]; (3) anxiety and depression, measured with the HADS (0–21 per subscale) [Citation24]; (4) pain-related fear, measured with the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK, 17–68) [Citation25,Citation26]; (5) Self-efficacy, measured with 10-itemed Pain Self Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ, 0–60) [Citation27]; and (6) global perceived effect (GPE), measured with a seven-point Likert scale ranging from ‘completely recovered’ to ‘worse than ever’, and ‘satisfied’ to ‘very dissatisfied’ [Citation28]. Patients furthermore completed the Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ) [Citation29,Citation30] directly after the first individual session to investigate the credibility and expectancy related to the treatment (credibility score 5–45, expectancy score 6–54). Directly after having received the entire intervention, patients were asked which intervention they thought to have received.

Data analysis

Baseline scores of Smeets et al. [Citation31] were used to calculate the sample size for this study. We aimed to detect a between-group difference of at least 15% on the QBPDS, which equals to 7 points in the study of Smeets et al. A two-tailed test with a significance level of 0.05, a power of 80%, and a dropout rate of 20% was used. In order to take the longitudinal design of the study into account, sample size calculation was adjusted for repeated measures. Sample size calculation resulted in 43 patients per group.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise baseline characteristics of patients. Frequencies are presented for categorical variables, means and standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed continuous variables, and medians and ranges for not normally distributed continuous data (i.e. baseline pain, anxiety and physical functioning). Baseline similarity was determined using chi-square tests for categorical variables, and independent t-tests or Mann–Whitney U (non-parametric) tests for continuous variables.

Linear mixed model analysis was used to determine between and within group differences over time, using the 3 × 3 identity covariance structure. No imputation strategy was needed since mixed model analysis allows for missing data. Patient was included as random factor. For each patient, there are three measurements: pre, post and 3 months after end of treatment. Treatment, time (three categories), and time × treatment were included as fixed factors. Baseline age, duration of LBP and sex were also considered in the model, but apart from duration of LBP in modelling HADS subscale depression and in modelling TSK, none of these were significant and therefore not included in the final model. The influence of credibility and expectancy on QBPDS outcome was determined by adding credibility and expectancy separately to the model. An interaction term (credibility × treatment or expectancy × treatment) was subsequently added to determine differences between treatment groups. Analysis was by intention-to-treat. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Flow of patients, therapists and centres

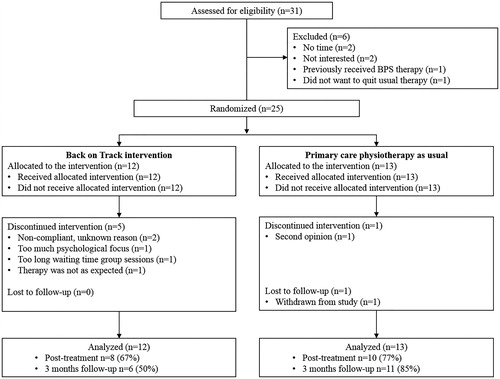

Thirty-one eligible patients were referred to the Back on Track study (). Twenty-five patients gave written consent and were randomised. provides baseline characteristics of randomised patients per intervention. The mean age of participating patients was 44 years (SD 12.2, range 18–62). Fifty-six percent was female (14 of 25). The level of psychosocial complaints was at group low as patients experienced a mean level of catastrophizing of 15 (SD 9.6), a median level of anxiety of 4 (range 0–18), a mean level of depression of 3.9 (SD 3.0), a mean level of kinesiophobia of 33 (SD 6.6), and a median level of physical functioning of 70 (range 20–95). There were no significant differences at baseline between the two groups, as well as between patients who discontinued or continued the intervention ().

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of study participants.

The Back on Track intervention was provided by four physiotherapists. Professional experience of physiotherapists ranged from no experience (just graduated) to 31 years of experience as physiotherapist. All four physiotherapists attended the three training sessions prior to the study.

Adherence to the study protocol

The average number of therapy sessions attended by patients in the Back on Track intervention was 7.9 (range 2–12). Over half of the patients met the compliance threshold (58%). Only patients who discontinued the intervention did not meet the compliance threshold (reasons are listed in ). Of the patients who did continue the intervention, three patients missed one session only. Reasons for non-attendance were: forgot to join the therapy session (n = 1), and unknown reasons (n = 2).

The average number of therapy sessions in the physiotherapy as usual intervention was 8.2 (range 3–12). The content of the physiotherapy as usual sessions mainly comprised of mobilisation techniques, core stability training, specific lower back exercises, massages and manual therapy. Directly after the intervention, one of the 19 patients who responded to the question to which intervention he or she was allocated to, did not know the allocation (Back on Track). Five patients indicated the allocation wrong and 13 patients the right intervention.

Effects of the interventions

Mixed model analyses showed no significant differences in functional disability between the Back on Track intervention and primary care physiotherapy as usual directly after treatment and at 3 months follow-up (). Mixed model analyses furthermore showed no significant between-group difference on other secondary outcomes at both time points. In addition, higher scores on credibility and expectancy did not significantly result in improvements in functional disability. Also its influence did not significantly differ between the intervention groups (p > 0.05). GPE scores at both time points also did not differ significantly between interventions (p > 0.05).

Table 3. Estimates of clinical effectiveness at post-treatment and 3 months follow-up.

During the study, no serious adverse events were reported. One adverse event was reported in the physiotherapy as usual group, but this was not related to the therapy (i.e. LBP due to fall from stairs at home).

Discussion

This pilot RCT investigated the difference in effectiveness between a biopsychosocial primary care intervention and primary care physiotherapy as usual in a subgroup of patients with CLBP. Patients included in this study experienced psychosocial complaints of low complexity which influence daily life functioning minimally. In the Netherlands, this subgroup of patients is usually referred to primary care physiotherapy treatments. The improvements in functional disability, as well as in other secondary outcomes, were not significantly different between the two interventions at post-treatment and 3 months follow-up. Based on these findings it can be suggested that none of the two therapies is better than the other in patients with CLBP in which psychosocial factors are only of minimal influence.

Participating physiotherapists who provided primary care physiotherapy as usual kept a log to get insight in the approach used. From the log it became clear that they provided mainly mobilisation techniques, core stability training, specific lower back exercises, massages and manual therapy. We considered this rather a biomedical approach than a biopsychosocial approach and, due to this, we do not think this has influenced the results.

Findings of this study are in line with findings of van der Roer et al. [Citation15] and Macedo et al. [Citation14] who both compared a Graded Activity intervention with another, more biomedically oriented, physiotherapy programme (guideline physiotherapy as usual and motor control exercises, respectively). These studies also found no differences in improvements in the level of functional disability between the interventions at short, medium and long term. Although the Back on Track intervention design differed from the Graded Activity interventions as it also included other cognitive-behavioural elements (e.g. exposure in vivo), these studies confirm the assumption that the type of therapy makes little difference for patients referred to a physiotherapy treatment in primary care.

Of notice is, however, that our study only included 25 patients in total, while it was powered at 86 patients. The lack of power makes interpretation of our results difficult and limits the comparison with other studies. It is possible that there were differences in effects, but the study was unable to detect them (type II error). Drawing conclusions and a direct comparison with mentioned studies should therefore be made with caution.

The inability to achieve the desired sample size was caused by the recruitment approach used. We considered recruitment via physicians important since physicians were specialised in chronic pain rehabilitation treatments, experienced in identifying psychosocial complaints and experienced in delivering pain education. We expected this would lead to the referral of a homogeneous group of patients, well-prepared for a biopsychosocial approach. In the time of receiving medical ethical approval for the study, Dutch legislation changed. Secondary care for patients with non-complex psychosocial complaints was discouraged and fewer patients were referred to physicians. Despite extra efforts to stimulate recruitment (i.e. by contacting general practitioners (GPs), physiotherapists and other health care specialists), the desired number of patients could by far not be achieved.

Another limitation was that more patients discontinued the Back on Track intervention than physiotherapy as usual. One reason was that the waiting time for group sessions was too long. The study had difficulties with generating groups, caused by the slow study recruitment. Patients therefore had to wait for group sessions to start. This was not an issue in the physiotherapy as usual intervention as it comprised of individual sessions only. An additional reason was that patients had different expectations about the Back on Track intervention. Physicians reported in focus group interview that, due to the allocation concealment, they could not properly prepare patients for a biopsychosocial intervention as they would usually do [Citation32]. So, the study procedures seem to have restricted physician’s usual care. To what extent this has influenced study outcomes is unknown.

A priori, we published our study protocol and considered this, in combination with the study design (a double-blinded RCT), a strength of the study [Citation17]. Randomisation seemed successful since baseline characteristics were equally distributed over interventions. We expected that patient blinding would be affected as patients might recognise the allocated therapy. Six patients either did not know or thought they were allocated to the other therapy. This indicates that blinding was maintained to some extent. An additional strength was that physiotherapists who provided the Back on Track intervention were satisfied with the training and could sufficiently deliver cognitive behavioural protocol elements [Citation32]. It is therefore assumed that the Back on Track intervention was provided as intended and delivery did not influence therapy outcomes.

For future studies, it can be recommended to reconsider the recruitment strategy, the biopsychosocial intervention design, and if desirable, the study design. Alternative recruitment strategies are via GPs or primary care physiotherapist. These are more frequently consulted by patients with low complex psychosocial complaints than physicians in secondary care nowadays. Additional screening tools might be helpful to ensure correct identification of patient’s psychosocial complaints [Citation33,Citation34] as previous studies have shown that GPs and physiotherapists seem not or only partially able to correctly identify psychosocial complaints [Citation35,Citation36]. As soon as the patient is allocated to the biopsychosocial intervention, the patient should be well-prepared for a biopsychosocial approach. Being well-prepared and satisfied with the therapy likely improves therapy compliance. Compliance in turn has been shown to optimise therapy effects [Citation37]. As therapy expectations did not always match and compliance was not optimal in our study, devoting an additional session to provide pain education and to discuss patient’s expectations might be required in future. Furthermore, group therapy should be considered only if recruitment or referral is sufficient to generated groups in time. An alternative study design could furthermore be recommended such as a single-case design in which a patient acts as its own control. This design requires less patients, although more frequent measurements and different logistics need to be performed [Citation38]. Overall, we expect that the discussed findings and recommendations will likely be helpful for developing future feasible, high-quality studies, which remain required to determine the difference in effectiveness between a biopsychosocial intervention in a primary care physiotherapy setting and primary care as usual for patients with CLBP.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Marion de Mooij for her assistance during the study; the Department of Rehabilitation in medicine MUMC + and physicians for the recruitment of patients; Dr. Paul Willems and members of the Spine Centre MUMC + and department of Anaesthesiology for referring patients; Fy’net Collaboration, dr. Frans Abbink (Fysiotherapiepraktijk Abbink), Tom Hameleers (ICL Fysio), Remco Reijnders & Germaine Neumann (Fysiohof), Yvonne Janss (Fysiotherapiepraktijk Yvonne Janss), Rick Kessels (Fysio Zuyd Caberg), Judith Giessen-Ploemen (Fysiotherapiepraktijk Giessen-Ploemen) for providing treatments to patients in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- RIVM. Ranglijst ziekten op basis van incidentie 2011. 2017. Available from: https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/ranglijst/ranglijst-ziekten-op-basis-van-incidentie

- Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, et al. Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:S192–S300.

- Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F, et al. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet. 2012;379:482–491.

- Stevens ML, Steffens D, Ferreira ML, et al. Patients' and physiotherapists' views on triggers for low back pain. Spine. 2016;41:E218–E224.

- Chou R, Shekelle P. Will this patient develop persistent disabling low back pain? JAMA. 2010;303:1295–1302.

- Koes BW, van Tulder M, Lin CW, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for the management of non-specific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:2075–2094.

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD000963.

- Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:CD002014.

- Hall A, Richmond H, Copsey B, et al. Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;21:1–9.

- Boonstra AM, Bühring M, Brouwers M, et al. Patiënten met chronische pijnklachten op het grensvlak van revalidatiegeneeskunde en psychiatrie. Ned Tijdschr Pijn Bestr. 2008;27:5–9.

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, et al. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Pract. 2019;19:224–241.

- Walti P, Kool J, Luomajoki H. Short-term effect on pain and function of neurophysiological education and sensorimotor retraining compared to usual physiotherapy in patients with chronic or recurrent non-specific low back pain, a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16:83.

- Vibe Fersum K, O'Sullivan P, Skouen JS, et al. Efficacy of classification-based cognitive functional therapy in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Pain. 2013;17:916–928.

- Macedo LG, Latimer J, Maher CG, et al. Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Therapy. 2012;92:363–377.

- van der Roer N, van Tulder M, Barendse J, et al. Intensive group training protocol versus guideline physiotherapy for patients with chronic low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:1193–1200.

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Koke AJA, et al. Development and content of the biopsychosocial primary care intervention 'Back on Track' for a subgroup of people with chronic low back pain. Physiotherapy. 2017;103:160–166.

- van Erp RM, Huijnen IP, Verbunt JA, et al. A biopsychosocial primary care intervention (Back on Track) versus primary care as usual in a subgroup of people with chronic low back pain: protocol for a randomised, controlled trial. J Physiother. 2015;61:155.

- Staal JB, Hendriks EJM, Heijmans M, et al. KNGF-richtlijn Lage-rugpijn. Amersfoort: Drukkerij De Gans; 2013.

- Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, et al. The Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Measurement properties. Spine. 1995;20:341–352.

- Schoppink LE, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, et al. Reliability and validity of the Dutch adaptation of the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Therapy. 1996;76:268–275.

- Smeets R, Koke A, Lin CW, et al. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ). Arthritis Care Res. 2011;63:S158–S173.

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–532.

- Van Damme S, Crombez G, Vlaeyen J. De Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Psychometrische karakteristieken en normering. Gedragstherapie. 2000;33:209–220.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370.

- Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Boeren RG, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363–372.

- Goubert L, Crombez G, Vlaeyen J, et al. De Tampa Schaal voor Kinesiofobie: Psychometrische karakteristieken en normering (The Tampa scale Kinesiophobia: psychometric properties and norms. Gedrag Gezond. 2000;28:54–62.

- Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11:153–163.

- Kamper SJ, Ostelo RW, Knol DL, et al. Global Perceived Effect scales provided reliable assessments of health transition in people with musculoskeletal disorders, but ratings are strongly influenced by current status. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:760–766 e1.

- Mertens VC, Moser A, Verbunt J, et al. Content validity of the credibility and expectancy questionnaire in a pain rehabilitation setting. Pain Practice. 2017;17:902–913.

- Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, et al. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:305–315.

- Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Hidding A, et al. Active rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: cognitive-behavioral, physical, or both? First direct post-treatment results from a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2006;7:5.

- Van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Köke AJA, et al. Feasibility of the biopsychosocial primary care intervention ‘Back on Track’ for patients with chronic low back pain: a process and effect-evaluation. J Physiother. 2015;61:155.

- Hill JC, Dunn KM, Lewis M, et al. A primary care back pain screening tool: identifying patient subgroups for initial treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:632–641.

- Linton SJ, Nicholas M, MacDonald S. Development of a short form of the Orebro Musculoskeletal Pain Screening Questionnaire. Spine. 2011;36:1891–1895.

- Jellema P, van der Windt DA, van der Horst HE, et al. Why is a treatment aimed at psychosocial factors not effective in patients with (sub)acute low back pain? Pain. 2005;118:3509.

- Synnott A, O’Keeffe M, Bunzli S, et al. Physiotherapists may stigmatise or feel unprepared to treat people with low back pain and psychosocial factors that influence recovery: a systematic review. J Physiother. 2015;61:68–76.

- Knox CR, Lall R, Hansen Z, et al. Treatment compliance and effectiveness of a cognitive behavioural intervention for low back pain: a complier average causal effect approach to the BeST data set. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:17.

- Onghena P, Edgington ES. Customization of pain treatments: single-case design and analysis. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:56–68.