Abstract

Purpose

Literature shows promising effects for interdisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation programs in patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP). Not every patient needs an interdisciplinary rehabilitation trajectory provided in a secondary care setting. Patients with moderate complex psychosocial complaints might benefit from biopsychosocial interventions offered in primary care under supervision of a physician in rehabilitation medicine (i.e. biopsychosocial integrated care intervention). This study investigated the feasibility and effectiveness of such intervention in patients with CLBP with moderate complex psychosocial complaints.

Methods

mixed-method. Patients (aged 18–65 years, low back pain ≥12 weeks, moderate complex psychosocial complaints) received the intervention (4 individual sessions, 8 group sessions) provided by trained primary care physiotherapists. Physicians in rehabilitation medicine provided one consultation afterwards. Data from patients (n = 18), physicians (n = 4) and physiotherapists (n = 12) were used.

Results

Physiotherapists were satisfied with the training. Patient attendance was good for individual sessions, less for groups. Physiotherapists sufficiently delivered the intervention, although recruitment and contextual factors influenced delivery. Patients reported significantly reduced functional disability (Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale) post-treatment (−8.3, 95% CI −13.3 to −2.7) and at 3 months follow-up (−7.6, 95% CI −12.9 to −2.2).

Conclusions

A biopsychosocial integrated intervention is feasible and potentially effective in patients with CLBP.

Introduction

For patients with chronic low back pain (CLBP) interdisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation programs (IBRPs) have been developed showing moderate but promising effects [Citation1,Citation2]. The general aim of IBRPs is to modify pain cognitions, stimulate active coping behaviour, and improve the level of functioning despite pain. IBRPs are often protocolled and extensive. Patients with CLBP however differ in biopsychosocial profiles. One patient might become fearful for experiencing pain, avoids daily activities, and in turn becomes disabled (e.g. fear-avoidance behaviour), while another patient copes well with pain and remains active [Citation3]. It is therefore suggested that patients’ treatment should match his/her biopsychosocial profile [Citation4–6].

In the Netherlands, the Task force Pain Rehabilitation of the Dutch Association for Rehabilitation Physicians (WPN-VRA) developed a classification system based on the complexity of the patient’s psychosocial complaints. The classification is applied by physicians to refer patients to the appropriate therapy setting [Citation7]. Mainly patients with moderate to high complex psychosocial complaints are referred to IBRPs in secondary or tertiary settings (i.e. hospitals, rehabilitation centres). Patients with low complex psychosocial complaints are referred to physiotherapy in primary care setting. The direct medical costs of IBRPs in secondary and tertiary care settings are high, placing a significant burden on the healthcare system [Citation8]. In addition, the number of patients treated in these settings has increased during the past years and is expected to increase even further [Citation9–11].

A potential solution for the increase of costs is to move IBRPs from secondary to primary care physiotherapy settings [Citation8]. In the Netherlands, direct medical costs of primary care physiotherapy treatments are lower. Further advantages are shorter waiting lists compared to secondary care treatments and treatment can be delivered closer to the patient’s home reducing travel time. To what extent patients who usually receive IBRPs in secondary care settings will benefit from biopsychosocial interventions provided in primary care, remains to be investigated. To date, no studies have been performed on this.

A biopsychosocial primary care physiotherapy intervention (‘Back on Track’) has therefore been developed for a specific subgroup of patients with CLBP, i.e. patients with moderate complex psychosocial complaints who would usually be referred to an IBRP in a secondary care setting. Physiotherapists are trained to provide this treatment. Patients are referred by a physician in rehabilitation medicine. This physician remains involved in the treatment and provides a final consultation at the end of the intervention. This results in an integrated care intervention.

Before evaluating the effectiveness of a newly developed intervention, it is important to investigate to what extent the intervention would be feasible, e.g. in terms of expectancies, fidelity (quality), dose delivered (completeness), dose received (exposure), reach (participation rate), recruitment, and context (environmental factors) [Citation12]. This information might, if desired or necessary, be useful to optimise the intervention for implementation, and will be useful for other researchers and clinicians who aim to develop, evaluate and/or implement a new biopsychosocial intervention.

The first aim of this study was to investigate to what extent Back on Track is feasible, in terms of expectancies, fidelity (quality), dose delivered (completeness), dose received (exposure), reach (participation rate), recruitment, and context (environmental factors) [Citation12] in patients with CLBP who experience moderate complex biopsychosocial complaints, and whether it is feasible to be provided by trained primary care physiotherapists. The second aim was to investigate to what extent patients would benefit from Back on Track (i.e. reduce the level of functional disability).

Materials and methods

This study included a mixed-methods design (e.g. questionnaires, focus groups, audio recordings), taking patients’ and healthcare providers’ perspectives into account. The Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC+, the Netherlands) approved the study (METC143024), and the Clinical Trial Centre Maastricht monitored the study. The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02245919) and has been carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki, 64th WMA General Assembly, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) for experiments involving humans.

Participants & settings

Physicians in rehabilitation medicine working at MUMC + referred patients with moderate complex biopsychosocial complaints to Back on Track (August 2014–May 2016). Patients fulfilled the following criteria were eligible; age between 18–65 years, LBP for ≥12 weeks, sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language, no specific cause for CLBP, no (underlying) psychiatric disease, and not pregnant. Physicians used the classification system developed by WPN-VRA. The complexity of the biopsychosocial complaints was determined by history taking and physical examination. If desirable, physicians used scores on multiple questionnaires although their own clinical opinion remained leading. Range scores for questionnaires that could be used as guidance were determined based on clinical data (MUMC+) and existing datasets from previous conducted studies [Citation13,Citation14]. Range scores for a moderate complex biopsychosocial profile included: Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) between 21–23, Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HADS, each subscale) between 8 and 11, RAND-36 item Health Survey (RAND-36, physical functioning subscale) of >35–42, and Pain Intensity Numeric Rating Scale (NRS, average pain last week) of >4. The physician provided pain education, prepared eligible patients for a biopsychosocial intervention and informed (oral and written information) patients about study participation. If patients were willing to participate, patients gave written consent to be contacted by the research team.

The research team invited patients for an intake at MUMC+. After study information was provided, patients gave written consent for study participation and completed baseline questionnaires. Patients gave written consent for the use of data from the questionnaires they completed prior to the first consultation with the physician. After intake, patients were referred to one of the participating physiotherapy practices.

In total four physiotherapy practices in the surroundings of Maastricht provided Back on Track. Practices were selected based on appropriate facilities (having a group therapy room), motivation and willingness to provide a biopsychosocial (group) therapy, as well as to participate in a scientific study and to receive a training program. Each practice assigned two physiotherapists to deliver Back on Track so that the second physiotherapist could act as back-up for the first one, e.g. during holidays or sick leave. Physiotherapists were trained during 3 sessions (4 h each) and received a treatment manual (for details of the training program, see elsewhere[Citation15]).

Back on Track consisted of 12 sessions; 3 individual educative sessions (30 min each), 8 group sessions (60 min each), and an individual evaluation session (30 min). The intervention ended with a final consultation of the referring physician. Back on Track aimed to improve the level of functional disability and to stimulate active coping behaviour. Reducing pain was not a direct goal. The role of the first individual sessions was to specify the individual pain problem (using the pain-consequence model) [Citation15], to educate about pain physiology and to define patient-specific goals. These individual sessions prepared patients for group sessions in which different cognitive-behavioural strategies were offered to stimulate active behaviour. Group sessions consisted of an educative part and a functional exercise part. Educative parts discussed dysfunctional beliefs, behaviour and strategies to improve the level of activities. In the functional exercise parts patients were stimulated to become physically active, to discuss patient’s behaviour while being active, and to improve self-confidence. The group sessions were structured around four themes (pain & physical activity, pain & social network, pain & cognitions, fact or myth?). A detailed description is provided elsewhere [Citation15]. Patients received a workbook including e.g. topics discussed during each session, assignments to reconsider own beliefs and behaviour, and self-management strategies to improve the level of activities at home. As described, Back on Track ended with a final consultation of the referring physician. The physician evaluated the progress, reinforced behaviour change and provided information for long-term adherence to active lifestyle.

Variables and data collection

Several measurement instruments, derived from patient, physicians and physiotherapists were used (). This triangulation approach gives a comprehensive overview and detailed understanding of the feasibility of Back on Track.

Table 1. Overview of measurement instruments used to assess the feasibility and effect evaluation elements.

Credibility and expectancy questionnaire

Patients and physiotherapists completed an adapted version of the Dutch Credibility and Expectancy questionnaire (CEQ) after the first individual treatment session to assess credibility and expectancy of Back on Track (i.e. ‘rehabilitation treatment was adapted to “treatment”’) [Citation16]. The questionnaire has good content validity, is easy to understand [Citation16], and scales have high internal consistency [Citation17]. The questionnaire included 5 questions for credibility and 6 for expectancy. Each item was answered with a 9-point rating scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much). Total score ranged from 5–45 for credibility and 6–54 for expectancy. A higher total score indicates a higher credibility or expectancy.

Attendance list: intervention (patients)

Attendance lists assessed attendance of patients during Back on Track and the final consultation with the physician. To our knowledge, no guidelines are available to define sufficient compliance for cognitive behavioural interventions. Therefore, a cut-off of having attended (at least) three individual sessions (session 1–3) and half of the group sessions (n = 4) was chosen, as we expected this number to be sufficient to understand and generalise learned cognitive behavioural principles.

Audio recordings: intervention

Physiotherapists audio recorded Back on Track sessions which were used to investigate to what extent physiotherapists delivered protocol elements as intended. A checklist based on the Method of Assessing Treatment Delivery was used [Citation18]. The checklist included four types of elements; i.e. essential and unique (EU), essential but not unique (E), unique but not essential (U), and prohibited (P). Each element was rated as ‘satisfactorily achieved’, ‘partially achieved’ or ‘not achieved’. Sufficient treatment delivery was defined as having on average ≥70% of the EU and E elements satisfactorily achieved [Citation18]. Furthermore, less than 10% of the P elements delivered during therapy was allowed. To select audio recordings for evaluation, first we gathered all available audio recordings and defined to which patient is belonged, and whether it was an individual or group session. Next, we randomly selected all recordings of three patients who completed the intervention (individual and group sessions), and all recordings of five patients who completed at least the first individual sessions (session 1–3). This resulted in a total of 50 from the 127 available audio recordings (39%) that were used to assess treatment delivery. This number is sufficient to calculate interrater reliability as stated by COSMIN criteria [Citation19]. A trainee and physiotherapist in chronic pain (CK and JN) who were not involved in the study but experienced in applying cognitive-behavioural treatment principles independently rated the audio recordings. Raters were trained using audio recordings not selected for the final assessment.

Evaluation form: intervention

A self-constructed evaluation form was completed by patients directly after the last session with the physician. This form investigated patient’s perceived knowledge, experiences and opinions about the intervention (per session), the physiotherapist and physician, and the workbook. The questionnaire included qualitative open-ended questions and quantitative questions, 48 in total. Quantitative questions used 5-point rating scales, ranging from totally agree to totally not agree, or very good to very bad. Patients also had to rate their general satisfaction with the intervention, physiotherapist, physician and the workbook on a scale from 0–10.

Focus groups

Focus groups were organised at the end of the study. One focus group was organised for participating physicians who referred patients to the study (2 h) and one for participating physiotherapists who delivered Back on Track (2 h). Both the focus groups were conducted by a male senior (AJAK) and student researcher. A semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions regarding pre-specified themes (e.g. expectancy, credibility, dose delivered, dose received and practical issues) was used to investigate experiences during the intervention. Both the focus groups were audio recorded.

Quebec back pain disability scale

Patients completed the Dutch version of the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS) at baseline, directly post-treatment and at 3 months follow-up to investigate changes in functional disability [Citation20]. Psychometric characteristics of the QBPDS are good [Citation20–22]. The QBPDS is a 20-itemed questionnaire with answering scale from 0 (not difficult at all) to 5 (unable to perform). A higher score indicates a higher functional disability level.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 22. Normality of baseline data was assessed with the Shapiro-Wilk test. Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for normally distributed continuous baseline variables. Otherwise, medians and range scores were reported. Frequencies were calculated for nominal and ordinal baseline variables. Differences in baseline characteristics between patients who continued or discontinued the intervention were compared with a Chi-square test and Mann-Whitney test (non-parametric).

Descriptive analysis (frequencies, means and SD, and medians and ranges) were performed for physiotherapists’ attendance and ratings regarding the training sessions, and patients’ attendance and ratings regarding Back on Track. Credibility and expectancy of patients and physiotherapists were compared (per item and total score) using the Mann-Whitney U test, and reported as median, range. CEQ scores of patients and physiotherapists were separately added as covariate to the final multilevel model (described below) to determine their potentially influential role on the QBPDS.

Ratings from the audio recordings of the Back on Track sessions were digitalised. Elements that could not be rated or were rated only once (such as sports activities), were deleted from the analysis. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using weighted Cohen’s kappa. The average score of EU, E, U and P elements delivered by physiotherapists was calculated as the mean proportion achieved over all rated sessions. Qualitative open-ended questions from the intervention evaluation form were gathered by one researcher (RMAVE). All identified experiences were reported in the manuscript. Reported results were reviewed by other co-authors. Focus group audio recordings were transcribed by a student researcher and checked by a second researcher (RMAVE). The transcript was independently coded and thematised by both researchers, taking into account pre-defined themes. Final codes and themes were discussed with a third researcher (AJAK) and chosen consensus-based. Data was analysed descriptively by thematic analysis. We aimed to report both positive and negative experiences. Findings were eventually checked by members for correct interpretation. Multilevel analysis (Linear mixed model analysis) was used to investigate improvements in QBPDS over time (repeated measures, time as fixed factor and patient as random factor) using the identity covariance structure. Age, sex, duration and intensity of low back pain were considered as covariates. Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

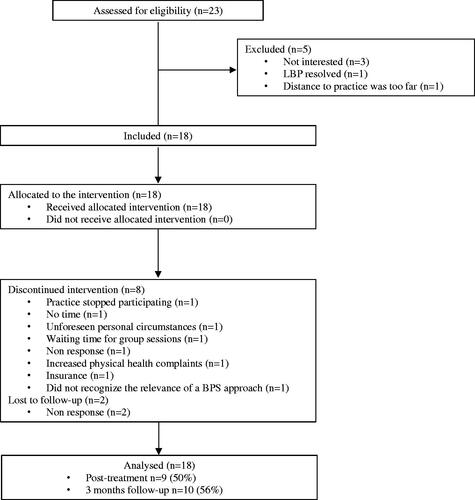

Eighteen of the 23 eligible patients participated in the study and received Back on Track (). Patients were mainly women with a mean age of 45 years (range 18–59) (). At group level, patients experienced moderate complex biopsychosocial complaints. At individual level, one patient seemed to experience less complex biopsychosocial complaints than expected by the physician (NRS score 2, PCS score 16, RAND-36 physical functioning score 80, HADS anxiety score 3, HADS depression score 2). Other patients had at least a pain score of >4 (NRS) and mostly one or more additional psychosocial complaints. Eight patients discontinued the intervention. They had significantly lower median pain intensity at baseline than patients who continued the intervention, i.e. 6 (range 2–8) versus 7 (range 6–10). Two of the 18 patients were lost to follow-up.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of study participants (patients).

Four physicians in rehabilitation medicine recruited patients for the study with a professional experience in CLBP rehabilitation ranging from 5–19 years. All four physicians attended the focus group.

The study started with the education of two physiotherapists per practice (n = 8). Four extra physiotherapists were educated since two physiotherapists quitted their job, one went on maternity leave and one seemed less available to deliver treatment. Four (three male and one female) physiotherapists eventually delivered Back on Track. The others acted as back-up and have not delivered Back on Track. Of the physiotherapists who delivered the intervention, one was graduated recently, two had 4 years of experience, and one had 31 years of experience. Three physiotherapists (75%) attended the focus group.

Credibility and expectancy

During the focus groups, physiotherapists as well as physicians reported that they considered the Back on Track intervention, prior to the start a credible and all-embracing intervention. One physiotherapist was concerned whether there would be sufficient time during individual session 2 (pain-education) to anticipate on the individual’s situation and questions. Another questioned whether it would be feasible to provide exposure in vivo elements and thought it would better fit psychologists.

Patients and physiotherapists did not differ in credibility and expectancy scores (p > 0.05), except that patients had significantly greater expectations that Back on Track would reduce the level of pain than physiotherapists (median 5.0, range 1–8 versus 2.5, 2–7, respectively).

Reach

The mean number of sessions patients attended during Back on Track was 8.3 ± 4.1 (range 2–12). In total, 67% of the patients met the compliance threshold. The attendance was higher during individual sessions (session 1–3) than during group sessions (). Lower attendance was due to discontinuance of the intervention (n = 6), holiday (n = 1), or unknown reasons (n = 4). Reasons for discontinuing the intervention are listed in . Eleven patients attended the final physician consultation. No session was planned for two patients (unknown reason), four did not show up (unknown reason), and one cancelled (patient reported not needing it).

Table 3. Attendance rates and mean satisfaction by patients per session of the Back on Track intervention.

Fidelity and dose delivered

Physiotherapists who delivered the intervention confirmed during the focus group that they were satisfied with the training program prior to the study, although implementation still seemed challenging as they were confronted with new complex situations. This was particularly the case when patients asked critical questions beyond the scope of the intervention. One physiotherapist noticed that experience is needed to manage complex situations (and interactions) more easily.

Physiotherapists reported that deviations from the protocol only occurred occasionally in case e.g. groups could not be formed. Two physiotherapists reported they had once merged two sessions into one because the group was small. According to the audio recordings, EU and E elements were on average satisfactorily achieved in 80% (±16.7), indicating sufficient protocol adherence (). Interrater reliability was fair (weighted Cohen’s kappa = 0.489). Those EU elements that were <70% satisfactorily achieved were mainly group session elements. One prohibited element occurred in 15% of the rated sessions (i.e. using medical diagnosis to explain the decreased level of daily life functioning’). This mostly occurred during theme 4 in which facts and myths about low back pain were discussed. It is unclear how the prohibited element was used; i.e. with a biomedical approach (indicating contamination), or to confirm the need for a biopsychosocial approach (indicating no contamination).

Table 4. Percentage of elements achieved during therapy sessions according to the ratings of audio recordings.

Considering specific protocol elements, physiotherapists seemed to be able to optimally discuss the patient’s LBP history, to define important functional activities and set a specific plan to enhance daily activity levels (Graded Activity; mean 100%, ). During the focus group, physiotherapists reported that Graded Activity elements had a clear structure and therefore went well. They mentioned that as soon as the topic became more personal and patients needed to speak about unpleasant situations, emotions or cognitions, patients waited for other group members to respond. According to the audio recordings, discussions about the vicious circle of negative thoughts and consequences of pain-behaviour were elements that were occasionally not addressed. Most patients however still reported that they learned how thoughts and emotions can influence coping behaviour (8/10), and that physiotherapists gave the opportunity to discuss their cognitions and emotions (9/11).

Defining the level of perceived threat value of daily activities was one element occasionally not addressed during therapy. One physiotherapist addressed that some patients did not recognise themselves in having fearful thoughts and avoidance behaviour.

Physical active sessions were largely not recorded due to practical reasons. These could therefore not be assessed by the raters. Physiotherapists mentioned it was not always possible to actually improve the level of the activity due to the limited time available. One physiotherapist explained his patients that physical active sessions were meant to improve the quality of activities and to reinforce behaviour. Patients needed to improve the level of activity (intensity/duration) themselves in their home situations. This was in line with the protocol.

Physiotherapists reported that few patients deviated from the protocol as they did not perform homework assignments in the workbook. Physiotherapists considered it however more important that patients would understand the information in the workbook and explain it themselves (realizing what they were doing), rather than just completing assignments. Over half of the patients (6/11) agreed at the end of the intervention that they would be able to improve their activity level themselves. Four patients responded neutral, and one patient disagreed.

Dose received

According to the evaluation form, patients reported general positive experiences with Back on Track. For example, good conversations with a laugh and a tear, understanding and humanity, focus on both physical and mental factors and thereby learning a lot about pain and themselves. Physiotherapists were also generally positive about Back on Track. Negative experiences of patients were the time for talking (too long) and active treatment (too short). Groups were too small and the time between the sessions was too long. Both physiotherapists and physicians agreed on this.

Patients valued the individual sessions on average higher (7.5 ± 1.0) than the group sessions (6.8 ± 2.1). Physiotherapists specifically addressed that pain education provided in individual sessions was most valuable and acted as the foundation for the intervention. They mentioned that the pain-consequence model was a valuable tool to define and understand a patient’s situation. Physiotherapists stressed however that sufficient understanding by patients is necessary to achieve improvements during therapy. Physiotherapists reported that patients who were aware of the situation and were willing to change, responded best to the intervention. Two physiotherapists argued that educative discussions within group sessions are more important than performing physical activities for which often less time was available. Patients however, expected more physical activities and confirmed that physical activities were not always performed during these sessions. This might have caused patients to value the physical active group session slightly lower than the educative group sessions (6.5 ± 2.6 and 7.1 ± 1.5, respectively).

Patients rated the final consultation with the physician as unsatisfactory (5.4 ± 4.0), but they rated the physician in person on average as satisfactory (7.9 ± 2.2).

Recruitment

Physicians and physiotherapists agreed during the focus groups, that the recruitment rate was disappointing. Patients were often too old, did not live in the surrounding or experienced too complex psychosocial factors. Due to this, patients reported that they needed to wait too long before a group could be formed and treatment started. They reported that this negatively influenced their motivation. Physiotherapists agreed and reported that groups were occasionally started with only two patients (with approval from the study team). Physiotherapists found it however challenging to stimulate interactive group discussions within such small groups. One physician stressed his concerns and questioned whether group sessions actually had achieved their maximal quality.

Context

During the focus group, physicians noticed that they managed the first consultation differently. Although physicians used similar pain-education elements, one physician provided pain-education as one package after history taking and physical examination, while others mixed these elements and started pain-education directly, based on what the patient reported.

Physicians and physiotherapists mentioned that communication between them occurred few times by email and never by phone. It often included logistic questions. Physicians would have appreciated more contacts as well as more in-depth reports from physiotherapists. This would have provided more insight in the type of therapy patients received. Physiotherapists mentioned it was unclear what they should have reported to the physicians as this was not protocolled and suggested guidelines for reporting in future. Physiotherapists furthermore reported that interim contacts with the physician might be ideal in future although they questioned the feasibility.

Physiotherapist mentioned that a protocolled intervention requires certain planning. They sometimes felt pressure to discuss all relevant topics in the specified timeframe for example in pain education in individual session 2. They also mentioned that planning group sessions was challenging. Physiotherapists had to deal with the low recruitment rate, working patients, and (in-)flexibility of the practice.

Effectiveness

Of the considered covariates, only low back pain intensity was of significant influence and was included in the final model. Mixed model analyses showed that patients reported a statically significantly decreased level of functional disability with on average 8.3 points (95% CI −13.9 to −2.7) (). At 3 months follow-up, the reduction remained constant and also statistically significant as compared to baseline.

Table 5. Estimates of improvements in functional disability at post-treatment and 3 months post-treatment.

Discussion

Summary of main outcomes

This study evaluated the integrated care intervention Back on Track. The intervention was applied to patients with moderate complex CLBP who were normally treated in secondary care. This study showed that with training, Back on Track seemed to be overall feasible in primary care physiotherapy practices for patients with moderate complex psychosocial complaints., and also resulted, although the number of patients was small in significant reduction of functional disabilities at group level, at short and medium term.

The process evaluation showed that the training program for primary care physiotherapists with different levels of professional experience was feasible and resulted in sufficient delivery of essential protocol elements during therapy. Our findings are in line with results of a recently published systematic review revealing that physiotherapists, if specifically trained and having resources available, can effectively deliver a biopsychosocial intervention [Citation24]. Although no guidelines are available for optimal training, it may be recommended discussing multiple cases and using role playing during the training program. Physiotherapists in our study mentioned that it was sometimes challenging to respond to new situations. Simulation of different situations might stimulate physiotherapist’s confidence in handling new situations. Furthermore, booster sessions and providing feedback during the intervention (coaching on the job) may further improve cognitive-behavioural skills and confidence of physiotherapists [Citation25,Citation26].

Both patients and physiotherapists were generally positive about the Back on Track intervention. Of all sessions, the individual sessions were appreciated most by patients and physiotherapists, and especially session 2 (by physiotherapists) in which pain education was provided. The pain-consequence model was considered a powerful tool to tackle biomedical beliefs and to direct into a biopsychosocial orientation. Changing the function of beliefs by challenging them (i.e. exposure in vivo elements), on the other hand, was sometimes difficult and/or less applicable. Exposure in vivo focuses on catastrophizing thoughts, pain-related fear and avoidance behaviour [Citation27]. Some patients however, reported low levels of catastrophizing thoughts at baseline (PCS range score 6–37), and furthermore did not recognise themselves in having pain-related fear or avoidance behaviour.

Previous studies showed that group therapy favours individual therapy as it can be cost-effective [Citation28] and stimulates patient interaction and societal integration [Citation29]. Despite the potential advantages, practical difficulties with generating groups were encountered, resulting in lower patient satisfaction. For example, patients attended the first individual sessions of the Back on Track intervention sufficiently, but their attendance dropped as soon as the group sessions started. The lower attendance was likely a consequence of the low recruitment rate causing an impaired group formation and increased waiting time to continue the program. The waiting time decreased motivation and eventually the attendance rate during groups. It should be stressed that, although group therapy is preferred, group therapy should be provided only if recruitment is appropriate and groups can be generated in time.

Our findings regarding effectiveness are in line with results from the Back Skills Training Trial. Although this study did not evaluate an integrated care approach, but rather a biopsychosocial primary care intervention, patients with chronic low back pain (and comparable biopsychosocial profiles) also reported significantly reduced levels of disability at post-treatment and follow-up [Citation30]. No causality could be established with our used pre-post-test design without a control group. Nevertheless, it was a first study to identify the potency of a new biopsychosocial integrated care approach eventually showing positive effects.

Implications for future

Back on Track may need some slight adaptations. First, more time should be incorporated for pain education. Devoting two individual sessions to pain education would be in line with a scientifically published practice guideline for pain (physiology) education [Citation31]. Second, whether an exposure session (theme 3, session 2) needs to be provided in the protocolled format, should be dependent on the patient’s psychosocial complaints. If a patient has less or no dysfunctional beliefs about pain and daily activities, a regular Back on Track physical active session may suffice. Third, physiotherapists should be encouraged to stick to the pre-specified time to perform physical activities as performing physical activities have significant benefits when added to education alone (i.e. significant reductions in pain) [Citation32], and this is in line with patients’ expectations what might increase therapy satisfaction. Fourth, communication and collaboration between physiotherapists and physicians in rehabilitation medicine need to be improved to ensure an integrated care approach. A contact moment could be added halfway; e.g. to discuss the applied therapy, define the future approach and integrate the physician’s knowledge into primary practice. A reporting format could furthermore be developed for physiotherapists with essential topics based on the expert opinion of physiotherapists and physicians. Finally, a long-term follow-up session might be beneficial to maintain or improve activity levels of patients. This booster session could be used to define the level of improvement/deterioration, to rehearse approaches learnt, and if necessary, to refer to a secondary care intervention. It should be noted that a considerable number of patients did not attend the final consultation with the physician. Therefore, it should be determined to what extent patients consider a follow-up session valuable and which health care professional should be involved.

Based on the promising findings of Back on Track, a future study to evaluate the cost-effectiveness between a biopsychosocial primary care intervention and IBRPs is needed. Therapy sessions of a primary care physiotherapy are less expensive compared to IBRPs. A cost-effectiveness study will give direction to whether care for this subgroup should be substituted to primary care.

Strengths & limitations

A major strength of this study was the use of multiple quantitative and qualitative measurement methods as well as multiple sources (physicians, physiotherapists and patients). We audio recorded focus groups and used audio recordings from session to evaluated protocol adherence by physiotherapists, what increased the reliability of the study. Furthermore, we asked physiotherapists and physicians to respond to our findings from the focus groups (member check), increasing the internal validity. We believe our study led to detailed insight in the implementation of an integrated primary care program into daily practice. Researchers and health care providers could benefit from such information as it can be useful for replication, improvement, and implementation of a biopsychosocial intervention in routine clinical practice.

One limitation of the study is the selection of physiotherapists. This was not based on their biopsychosocial orientation. Literature showed that therapist’s orientation (biomedical versus biopsychosocial) can influence therapy delivery and the advice they provide [Citation33,Citation34]. Nevertheless, our physiotherapists were motivated to provide a biopsychosocial intervention and were offered a training program. Although not evaluated afterwards, physiotherapists’ orientation was considered sufficient as they delivered biopsychosocial protocol elements sufficiently.

A second limitation was the small sample size (n = 18 patients) in the study, a consequence of having only one centre recruiting patients. This limits the possibility to generalise findings to a larger population (external validity). Extra efforts were taken to increase the sample size such as contacting other health care specialists to refer potential patients to the department of rehabilitation medicine. These efforts however did not have the desired effect. It is recommended for future studies to use multiple centres recruiting patients. These centres should be specified in chronic pain rehabilitation and treat sufficient numbers of patients with CLBP and moderate to complex psychosocial complaints.

Another limitation was the rather low interrater reliability between the two raters of the audio recordings. This was likely a consequence of using a three-point rating scale (instead of two). Three options would give insight to what extent elements were provided. This was considered useful to optimise the intervention and the training program. It however also introduced subjectivity within the ratings. Despite training our raters, it was not sufficient to overcome subjective dissimilarities. Therefore, results from the audio recordings should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, this study demonstrates that an integrated biopsychosocial intervention is feasible and potentially effective in reducing functional disability in patients with CLBP who experience moderate complex psychosocial complaints. The study can act as a preliminary study for high-quality clinical trials in which the cost-effectiveness of an integrated biopsychosocial intervention will be compared with regular secondary care interventions in patients with CLBP.

Acknowledgements

First, the authors thank Marion de Mooij for her support and assistance during study. The authors acknowledge Paul Willems, Frans Abbink and Marlies den Hollander for their help in the development of Back on Track, and thank all participating patients for receiving the intervention and to express their experiences. Thanks to the participating physiotherapists, especially those who delivered Back on Track, audio recorded therapy sessions, and participated in the focus groups (Tom Hameleers, Frans Abbink, Remco Reijnders and Germaine Neumann). The authors thank the Department of Rehabilitation in medicine MUMC+, Spine Center MUMC + and Fy’net Collaboration for facilitating the delivery of the Back on Track intervention, as well as physicians (Marieke van Beugen and Robin Strackke) for delivering the Back on Track consultations and participating in the focus groups. Many thanks to Celine Kieftenburg and Jana Naumann who rated the audio recordings, and Arjan Kooistra who conducted the focus groups and the related analysis. Also, The authors thank Ton Ambergen for his help performing the statistical analyses, and to interpret and report the results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kamper SJ, Apeldoorn AT, Chiarotto A, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. Cochr Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD000963.

- Salathé CR, Melloh M, Crawford R, et al. Treatment efficacy, clinical utility, and cost-effectiveness of multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation treatments for persistent low back pain: a systematic review. Global Spine J. 2018;8(8):872–886.

- den Hollander M, de Jong JR, Volders S, et al. Fear reduction in patients with chronic pain: a learning theory perspective. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(11):1733–1745.

- Scerri M, de Goumoens P, Fritsch C, et al. The INTERMED questionnaire for predicting return to work after a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program for chronic low back pain. Joint Bone Spine. 2006;73(6):736–741.

- George SZ, Fritz JM, Bialosky JE, et al. The effect of a fear-avoidance-based physical therapy intervention for patients with acute low back pain: results of a randomized clinical trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)). 2003;28(23):2551–2560.

- Linton SJ, Nicholas M, Shaw W. Why wait to address high-risk cases of acute low back pain? A comparison of stepped, stratified, and matched care. Pain. 2018;159(12):2437–2441.

- Boonstra AM, Bühring M, Brouwers M, et al. Patiënten met chronische pijnklachten op het grensvlak van revalidatiegeneeskunde en psychiatrie. Nederlands Tijdschrift Voor Pijn en Pijnbestrijding. 2008;27(34):5–9.

- Van Eijndhoven M, Gaasbeek Janzen M, Latta J, et al. Rapport Medisch-specialistische revalidatie: zorg zoals revalidatieartsen plegen te bieden. Zorginstituut Nederland; 2015.

- Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(6):2028–2037.

- Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, et al. Epidemiology of low back pain in adults. Neuromodulation. 2014;17(Suppl 2):3–10.

- Eerste Kamer der Staten-Generaal. Onderhandelaarsresultaat medisch specialistische zorg 2014 t/m 2017. Accessed 5 Sept 2018. Available at https://www.eerstekamer.nl/overig/20130716/onderhandelaarsresultaat_medisch/document.

- Saunders RP, Evans MH, Joshi P. Developing a process-evaluation plan for assessing health promotion program implementation: a how-to guide. Health Promot Pract. 2005;6(2):134–147.

- Leeuw M, Goossens ME, van Breukelen GJ, et al. Exposure in vivo versus operant graded activity in chronic low back pain patients: results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2008;138(1):192–207.

- Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Hidding A, et al. Chronic low back pain: physical training, graded activity with problem solving training, or both? The one-year post-treatment results of a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2008;134(3):263–276.

- van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Koke AJA, et al. Development and content of the biopsychosocial primary care intervention 'Back on Track' for a subgroup of people with chronic low back pain. Physiotherapy. 2017;103(2):160–166.

- Mertens VC, Moser A, Verbunt J, et al. Content validity of the credibility and expectancy questionnaire in a pain rehabilitation setting. Pain Pract. 2017;17(7):902–913.

- Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, et al. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(4):305–315.

- Leeuw M, Goossens ME, de Vet HC, et al. The fidelity of treatment delivery can be assessed in treatment outcome studies: a successful illustration from behavioral medicine. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(1):81–90.

- De Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- Schoppink LE, van Tulder MW, Koes BW, et al. Reliability and validity of the Dutch adaptation of the Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale. Phys Ther. 1996;76(3):268–275.

- Kopec JA, Esdaile JM, Abrahamowicz M, et al. The Quebec back pain disability scale. measurement properties. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)). 1995;20(3):341–352.

- Smeets R, Koke A, Lin CW, et al. Measures of function in low back pain/disorders: Low Back Pain Rating Scale (LBPRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Progressive Isoinertial Lifting Evaluation (PILE), Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), and Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RDQ). ).Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken)). 2011;63 (Suppl 11):S158–S173.

- Leeuw M, Goossens ME, van Breukelen GJ, et al. Measuring perceived harmfulness of physical activities in patients with chronic low back pain: the Photograph Series of Daily Activities–short electronic version. J Pain: 2007;8(11):840–849.

- Hall A, Richmond H, Copsey B, et al. Physiotherapist-delivered cognitive-behavioural interventions are effective for low back pain, but can they be replicated in clinical practice? A systematic review. Disabil Rehabil. 2018;40(1):1–9.

- Van Erp RMA, Huijnen IPJ, Jakobs MLG, et al. Effectiveness of primary care interventions using a biopsychosocial approach in chronic low back pain: a systematic review. Pain Pract. 2019;19(2):224–241.

- Holopainen R, Simpson P, Piirainen A, et al. Physiotherapists' Perceptions of Learning and Implementing a Biopsychosocial Intervention to Treat Musculoskeletal Pain Conditions: A Systematic Review and Metasynthesis of Qualitative Studies. Pain. 2020;161(6):1150–1168.

- Vlaeyen JW, de Jong J, Geilen M, et al. Graded exposure in vivo in the treatment of pain-related fear: a replicated single-case experimental design in four patients with chronic low back pain. Behav Res Ther. 2001;39(2):151–166.

- Critchley DJ, Ratcliffe J, Noonan S, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of three types of physiotherapy used to reduce chronic low back pain disability: a pragmatic randomized trial with economic evaluation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976)). 2007;32(14):1474–1481.

- Carnes D, Homer KE, Miles CL, et al. Effective delivery styles and content for self-management interventions for chronic musculoskeletal pain: a systematic literature review. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(4):344–354.

- Lamb SE, Hansen Z, Lall R, et al. Group cognitive behavioural treatment for low-back pain in primary care: a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9718):916–923.

- Nijs J, Paul van Wilgen C, Van Oosterwijck J, et al. How to explain central sensitization to patients with 'unexplained' chronic musculoskeletal pain: practice guidelines. Man Ther. 2011;16(5):413–418.

- Louw A, Zimney K, Puentedura EJ, et al. The efficacy of pain neuroscience education on musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of the literature. Physiother Theory Pract. 2016;32(5):332–355.

- Bishop A, Foster NE, Thomas E, et al. How does the self-reported clinical management of patients with low back pain relate to the attitudes and beliefs of health care practitioners? A survey of UK general practitioners and physiotherapists. Pain. 2008;135(1-2):187–195.

- Darlow B, Fullen BM, Dean S, et al. The association between health care professional attitudes and beliefs and the attitudes and beliefs, clinical management, and outcomes of patients with low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2012;16(1):3–17.