Abstract

Objectives

The PainDETECT Questionnaire (PD-Q) is a self-reported questionnaire aiming to assist in detecting neuropathic pain in individual patients. However, measurement properties of the Norwegian translated version should be examined, and the aim of the present study was to examine its test-retest reliability.

Methods

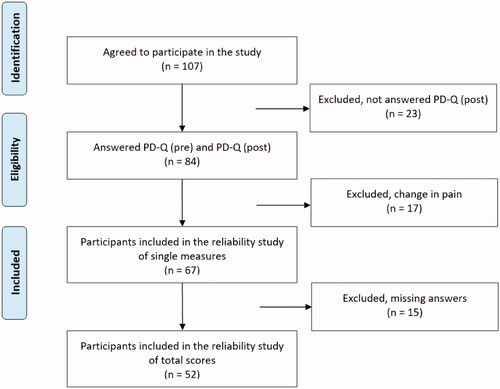

A total of 107 patients were initially recruited to the study from physiotherapy clinics. After screening for inclusion- and exclusion criteria, 67 participants remained for examining reliability of separate items. They were to fill out the PD-Q twice at an interval of 14 days. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and standard error of measurement (SEM) of total scores, and Kappa statistics and percentage of agreement of separate items and screening data were used in the analysis.

Results

Fifty-two participants filled out all items correctly, a prerequisite for determining the reliability of the total score and screening category. The ICC for the total score was 0.84 (95% confidence interval 0.73–0.91), SEM 2.5. The Kappa value for the screening category was 0.50 (95% confidence interval 0.31–0.69), and percentage of agreement 69%. Single items were found with reasonable to substantial reliability.

Conclusion

The Norwegian version of the PD-Q showed good test-retest reliability for the total score, but only moderate reliability of the screening category classifying the likelihood of neuropathic pain. The high number of missing answers indicates that some guidance from a health care professional is needed when filling out the questionnaire.

Introduction

Neuropathic pain is associated with injury or disease of the nervous system [Citation1,Citation2] and is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain as ‘pain arising as a direct consequence of a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory system’ [Citation3]. Several diseases have a neuropathic pain component, such as radiculopathy, diabetic neuropathy, multiple sclerosis, cancer and stroke [Citation1,Citation4,Citation5]. Trauma resulting in nerve injury can also cause neuropathic pain [Citation6,Citation7].

There is a wide range of signs and symptoms indicating neuropathic pain, such as spontaneous pain, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and dysesthesia [Citation2,Citation6–8]. Patients describe the pain as shooting, burning or stabbing, and they often report a feeling of tingling, electric shock and numbness [Citation2,Citation4,Citation6,Citation9]. As the lesion can be localised in the central or peripheral nervous system patients can present with hypo- or hyperreflexia, and the pain distribution will vary accordingly [Citation6,Citation10].

Patients with neuropathic pain also report lower quality of life than patients with other chronic illnesses and they typically describe their pain as more intense [Citation6,Citation11]. In addition, these patients seek more health care services and retire earlier than the average population resulting in increased cost to society [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation12]. Early diagnosis and thereby early treatment have shown to improve the prognosis [Citation12,Citation13]. At present there is no gold standard for diagnosing neuropathic pain [Citation1,Citation2,Citation6,Citation10], but several screening questionnaires have been developed to assist the clinician in detecting neuropathic pain in a primary care setting [Citation2,Citation6].

The PainDETECT questionnaire (PD-Q) was originally developed in Germany with the aim of detecting neuropathic pain in patients with low back pain [Citation12]. A test-retest reliability study of the German PD-Q was later conducted, finding excellent reliability for the total score, intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) being 0.93 [Citation14]. This screening tool has been translated into 38 languages, including Norwegian [Citation15].

Several studies of PD-Q translations have shown excellent reliability for patients with a wide variety of diagnosis recruited from pain clinics, finding ICCs of 0.97, 0.94, and 0.93 for the total score in the Arabic [Citation16], Japanese [Citation17], and Spanish [Citation18] versions, respectively. However, a Swedish study demonstrated moderate test-retest short-term reliability for the total score of patients with central neuropathic pain [Citation19]. The studies of the English [Citation11] and German [Citation14] PD-Q are the only examining reliability of the screening category as well as the individual items of the questionnaire, Kappa ranging from 0.29 to 0.89. The time interval between PD-Q (pre) and PD-Q (post) varied in the different studies from one hour in the Arabic [Citation16], English [Citation11] and Swedish [Citation19] studies to three months in the Dutch [Citation20].

It has been reported that participants often fail to answer all the PD-Q questions, preventing calculation of the total PD-Q score [Citation11,Citation17]. The prevalence of missing answers has varied between 12 and 35% [Citation18,Citation20–22]. Missing answers are mainly found for the question; ‘Does your pain radiate to other regions of your body?’ [Citation11,Citation17,Citation18]. In the English reliability study this question was responsible for 80% of the missing answers [Citation11]. In the German reliability study, however, the participants filled in the answers on a handheld computer and were required to answer all questions, avoiding missing answers [Citation14]. Another problem encountered was scoring on the body chart. Although the participants are asked to only mark their main area of pain on the body chart, 42–56% of them marked more areas [Citation11,Citation23]. These shortcomings may influence the scoring of separate items, affecting sum scores.

The PD-Q has been translated into Norwegian (by MAPITM) [Citation15], but the translated questionnaire has not been examined for reliability. The aim of the present study was to examine test-retest reliability and measurement error or percentage of agreement of all aspects of the questionnaire; the separate items, the total score, and the screening category.

Methods

A test-retest design, with repeated testing 14 days apart, was used. The Regional Committees for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) approved the study (2018/911). It was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

To ensure sufficient valid data for the test-retest reliability study, 107 participants were recruited from patients presenting at two physiotherapy clinics from August 2018 to July 2020. To secure generalisability, the following inclusion criteria were used: patients older than 18 years with pain lasting more than three months, regardless of diagnosis or pain localisation. They had to be able to write and speak Norwegian and give written consent to participate in the study. As the patients in a test-retest study are assumed to be rather stable on the construct to be measured, exclusion criteria was Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) ≤2 or ≥6 at re-test, implying major changes in their perceived pain. The physiotherapist diagnosed the patient based on information from the first consultation. For patients with for example neurological disorders the patients had been diagnosed before by their general practitioner or a specialist in neurology.

Sample size

A sample of at least 50 patients was required to examine test-retest reliability of the different parts of the questionnaire, as recommended by de Vet et al. [Citation24]. According to COSMIN guidelines regarding design requirements for studies of reliability, a total of 50–99 patients are considered adequate [Citation25]. A power calculation performed in a previous Swedish study [Citation19], using an alpha-level of 0.05, revealed that 40 individuals would give a power of at least 80% to detect a true kappa coefficient of 0.75 or more as statistically different from 0.20 (fair). A sample of at least 50 patients was accordingly considered sufficient in our study.

Study protocol

Patients were asked to participate in the study at their first appointment with the physiotherapist. If they agreed to participate, they signed a written consent form and filled out the PD-Q (pre), on paper, alone without any help from the physiotherapist. After the consultation, the patients received a prepaid envelope with PD-Q (post) and Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC), a self-report measure to report whether their painful condition had changed to the better or worse since the first assessment. They were asked to fill out the questionnaires 14 days after the consultation and send the envelope back by mail.

Measurement tools

PainDETECT (PD-Q)

The PD-Q [Citation12] is a self-reported questionnaire that consists of four sections. The first part describes pain intensity by using three 11-point numeric rating scales (NRS) measuring the patient’s current, average, and strongest pain for the last 4 weeks. Part two consists of a body chart where the patient is to mark only the main area of pain and to answer a ‘yes/no’ question regarding radiating pain. Part one is not included in the total PD-Q score, while answering ‘yes’ to radiating pain in part two adds two points to the total PD-Q score.

Part three relates to the course of pain asking the participant to choose one of four pictures with the descriptions ‘Persistent pain with slight fluctuations’ (0 point), ‘Persistent pain with pain attacks’ (-1 point), ‘Pain attacks without pain between them’ (1 point) and ‘Pain attacks with pain between them’ (1 point).

Part four consists of seven descriptive symptoms (burning sensation, tingling/prickling sensation, sensitivity for light touch, sudden pain attacks like electric shocks, cold/heat sensitivity, numbness, and pressure-evoked pain), each scored from 0 (never) to 5 (very strongly).

The total score of the PD-Q ranges from 0 to 38 and is divided into the three categories ‘unlikely’ neuropathic pain (0–12), ‘ambiguous’ neuropathic pain [Citation13–18], and ‘likely’ neuropathic pain [Citation19–38].

Patient global impression of change scale

Patients should not experience a marked change between test and retest in reliability studies. The Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) scale is a questionnaire with a 7-point numerical rating scale developed to detect changes in a patient’s experience of a symptom [Citation26,Citation27]. It is considered the gold standard for measuring a person’s perception of change over time [Citation27,Citation28]. The patients rate their experience of change as ‘very much improved’, ‘much improved’, ‘minimally improved’, ‘no change’, ‘minimally worse’, ‘much worse’, or ‘very, much worse’ [Citation5,Citation27]. A score ≤2 and ≥6 is considered a significant change in symptoms, while they are considered rather unchanged if the score is between 3 and 5. The PGIC was used to ensure that no major changes in the patients’ symptoms occurred between PD-Q (pre) and PD-Q (post) [Citation26,Citation27].

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed by SPSS (version 25). Descriptive data was presented as n (%), mean (SD), and minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance, p < 0.05.

ICC statistics, two-way random, absolute agreement, was used for examining test-retest reliability of the 11-point numerical rating scales (part 1), as well as the PD-Q total score. An ICC score <0.50 is considered ‘poor’, 0.50–0.74 ‘moderate’, 0.75–0.89 ‘good’, and ≥0.90 ‘excellent’ [Citation29]. Standard error of measurement (SEM) was calculated in the ICC analysis, based on the information from the analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the following formula: Sw=√total mean square [Citation24].

Kappa statistics and percentage of agreement was used for examining reliability of the questions regarding radiating pain (yes/no, part 2), pain pattern (score −1 to 1, part 3), the seven pain descriptors (score 0–5, part 4) and the three-point classification regarding certainty of neuropathic pain based on the total score. A Kappa score <0.20 is considered ‘weak’, 0.21–0.39 ‘reasonable’, 0.40–0.59 ‘moderate’, 0.60–0.79 ‘substantial’, and ≥0.80 as ‘almost perfect’ [Citation30]. 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated for both ICC and Kappa values. Cut-off values for the screening category ‘negative’ to ‘ambiguous’ was set to 12 points and 18 points for ‘ambiguous’ to ‘positive’ in the Norwegian PD-Q [Citation15]. This is in line with the English version [Citation11].

Results

A total of 107 participants agreed to take part in the study. All filled out the first questionnaire, PD-Q (pre), and 84 (78%) returned the second questionnaire, PD-Q (post), as well as the PGIC. illustrates the process of inclusion and exclusion. Due to missing data, reliability of the separate items was calculated in 55–67 participants, while the total score and screening category were calculated in 52 participants.

Participant characteristics

The different parts of the study included a maximum of 67 participants, 69% women, mean age 57 years (SD 14.3), ranging from 18 to 84. The mean duration of symptoms was 127 months (SD 171), ranging from 3 to 684 months. There was a great variation in diagnosis (), the majority having musculoskeletal pain (79%). Neurological disorders included cerebral palsy, neuropathy, Parkinson’s disease, syringomyelia, and stroke.

Table 1. Overview of the participants’ characteristics, N = 67.

Most participants (78%) used one or more medications in the subgroups [Citation31] listed in . One or more analgesics, such as Paracetamol, Paralgin Forte, or Tramadol, was used by 43%. Medication recommended for treatment of neuropathic pain, such as Lyrica and Neurontin [Citation32,Citation33] was used by 13%.

Missing answers

From the group of 67 participants 15 (22%) failed to answer one or more questions of the PD-Q. The questions regarding radiating pain and pain patterns were most often missed (). Three participants informed that none of the pain pattern options corresponded with their pain experience which was the reason why they did not respond.

Table 2. Missing answers PD-Q, N = 67.

Reliability

Part 1 – pain intensity

Test-retest reliability for the pain intensity scales variated from ICC = 0.70 (95% CI 0.55-0.80), SEM 1.02. (average pain the past four weeks) to ICC = 0.78 (95% CI 0.67–0.86), SEM 0.90. (maximum pain the past four weeks) ().

Table 3. Test-retest reliability of pain intensity, N = 67.

Part 2 – body chart and radiating pain

All but one of the 67 participants filled in the body chart, but approximately one third marked more than one pain area on the chart.

The Kappa value for the question regarding radiating pain (yes/no) was 0.71 (95% CI 0.51–0.91) (). The majority (69%) answered yes, implying that they had radiating pain. Percentage of agreement was 91% ().

Table 4. – Test-retest reliability of separate items in part 2, 3 and 4, N total = 67.

Table 5. Overview of percentage of agreement of separate items in part 2, 3 and 4, N total = 67.

Part 3 – pain patterns

The participants were to choose one of four pain patterns depending on which pattern that best described his or her pain. Two failed to answer the question. The kappa value was 0.59 (95% CI 0.43–0.74) (), and percentage of agreement 69% ().

Part 4 – descriptive symptoms

The questions regarding four of the seven descriptive pain characteristics were answered by all participants, while the question of ‘burning sensation’, ‘sudden pain attacks’ and ‘pain with light touch’, where not scored by 1–3 participants. Kappa for the seven symptoms ranged from 0.35 (95% CI 0.20–0.50) to 0.50 (95% CI 0.33–0.67) (). describe the percentage of agreement for each pain descriptor, ranging from 47% (pressure evoked pain) to 73% (sensitivity to heat or cold).

Total score

The average total score for PD-Q (pre) and PD-Q (post) was 12.4 (SD 6.4) and 12.6 (SD 6.1), respectively, and the difference was not statistically significant, p = 0.70. Test-retest reliability was good, ICC = 0.84 (95% CI 0.73–0.91), SEM 2.5.

Screening category

The Kappa value for the screening category was 0.50 (95% CI 0.31–0.69) (), and percentage of agreement was 69% ().

Table 6. Overview of the PD-Q screening data, N = 52, Kappa = 0.50 (95% CI 0.31–0.69).

Discussion

This study aimed to examine test-retest reliability of the Norwegian PD-Q. Reliability of the separate test items varied between reasonable and substantial, while it was good for the total score and moderate for the screening category. Fifty-two participants answered all required items of the questionnaire, allowing for reliability analysis of the total score and screening category. The number of participants included in these two important parts of the questionnaire became lower than what was aimed for at study start but is still in line with the COSMIN guidelines [Citation25], recommending at least 50 participants in reliability studies, and is above the sample size of 40 calculated in a Swedish study [Citation19].

Several studies have documented excellent reliability for the total score at their respective language versions. The Arabic version had the highest reliability score with ICC = 0.97 [Citation16]. This study had, in line with the studies of the Swedish and English versions, a test-retest time interval of only one hour [Citation11]. Studies with a time interval of one week to three months demonstrated good, but lower reliability, ranging from ICC = 0.79–0.87 [Citation11]. This indicates that the short-term interval (one day to one week) may cause recall bias leading to an artificially high reliability [Citation24]. There is, however, no consensus on the optimal time interval between assessments [Citation24,Citation34,Citation35]. Fourteen days was chosen as it is described to be long enough to reduce the risk of recall bias, and at the same time reduces the chance of changes in the participants’ symptoms [Citation24]. The test-retest reliability of the total score of the Norwegian PD-Q is in line with the Dutch [Citation20] version, both having a two-weeks interval, with ICC = 0.84 and 0.83, respectively.

Test-retest reliability of the PD-Q screening category, was previously only examined in the English [Citation11], German [Citation14], and Swedish [Citation19] versions. When interpreting the Kappa value for these three studies, the reliability was considered moderate to almost perfect [Citation24,Citation30,Citation36], ranging from 0.50 to 0.82. The Norwegian PD-Q had the lowest reliability even though this version used the same cut-off value as the English and German versions. The choice of cut-off values may have a great influence on the test-retest reliability of the screening tool [Citation24]. In studies examining the PD-Q discriminating ability, different cut-off values have been found. The lowest cut-off score (≥8) for distinguishing neuropathic pain from non-neuropathic pain was found for the Swedish translated version [Citation19]. In comparison, the Spanish version of PD-Q had the highest cut-off score, ≥17 [Citation18]. In the Norwegian PD-Q 31% of the participants changed screening category from PD-Q (pre) to PD-Q (post). The average total score was 12.4 (SD 6.4) and 12.6 (SD 6.1) for PD-Q (pre) and PD-Q (post), respectively. The cut-off score for ‘ambiguous’ neuropathic pain is set to 13-18. A change in total score by one point can therefore result in a change of screening group. Whether a more favourable cut-off value should be used in the Norwegian version to improve discriminative ability, remains to be seen.

Previous studies have not reported reliability values for each item of the PD-Q, except for the English [Citation11] and German [Citation14] studies. In general, the English study demonstrated similar or better reliability values for the individual items than our study. An exception was pain patterns (part 3) where Kappa was 0.29 in the English [Citation11] study and 0.59 in the Norwegian. The shorter time interval of one week in the English study is hypothesised to be a reason for finding this version more reliable. The German [Citation14] version showed higher test-retest reliability for all 7 pain descriptors than both the English [Citation11] and Norwegian versions. The former had the same time interval as our study, but the participants got specific instructions on a handheld computer to answer the questions in relation to their main pain area. Instructions on the paper form do not specify this, and it is uncertain if the given information was understood.

When comparing the reliability values for the individual items of the PD-Q in our study, ‘radiating pain’ (part 2) and ‘pain patterns’ (part 3) demonstrated substantial (Kappa = 0.71) and moderate (Kappa = 0.59) test-retest reliability, respectively. However, reliability of the descriptive symptoms in part 4 range from weak to moderate (Kappa = 0.36–0.50), percentage of agreement ranging from 47 to 73%. This is in line with the findings in the English study [Citation11]. The different number of answering options in individual items of the PD-Q can contribute to differences in reliability values between them [Citation24].

In this study the participants filled out the PD-Q (pre) and PQ-Q (post) alone as the questionnaire is designed to be used without further guidance [Citation37]. The information given to the participant in advance can, however, affect the participants’ answers and thereby affect reliability of the questionnaire [Citation24]. Other study reports have not described whether the participants were given additional information before filling out the questionnaire, or not. A comparison between the applied study protocols in the different studies is therefore not possible.

Little information is available regarding the development and validation of the questions included in the PD-Q. The developers of the German PD-Q [Citation12] described conducting a literature search and interviews to decide which words that best describe neuropathic pain. Then a validation study of the screening category was conducted including 411 patients with low back pain where the diagnosis was determined by two independent pain specialists. Examination of content validity was, however, not carried out, exploring comprehensiveness, comprehensibility, and relevance. Comprehension of items of the questionnaire is important to avoid missing, and to derive valid answers [Citation24].

Authors of the English [Citation11] and Dutch [Citation20] studies have reported challenges with filling out the questionnaire in regard to missing answers and interpretation of questions. In the original German study [Citation12] 20% of the participants had difficulties answering the questionnaire. However, a solution to this problem was not suggested. Several other studies [Citation11,Citation16,Citation18,Citation22] also report similar problems with missing values. Three participants in our study wrote on the form, at their own initiative, that they chose not to answer ‘pain patterns’ (part 3), as none of the illustrations described their pain experience. This could also be the reason why other participants did not answer this question. The same reason for not answering the question has been reported in the English and Dutch studies [Citation11,Citation20]. The question regarding ‘radiating pain’ (part 2) was the most frequent missing item in our study (19.4%). The reason for the low response is not known, but an unfavourable location of the question on the form is suggested.

The written instruction, informing that only the main area of pain shall be marked on the body chart (part 2), might be difficult to see on the paper form by the participants and can explain why more than one area was marked by many. In addition, patients with long-lasting pain often present with widespread pain [Citation38]. In our cohort several of the diagnosis, such as central sensitisation, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid arthritis present with multiple pain sites [Citation9]. This is also hypothesised to explain why participants marked more than one area of pain. As the questions in the PD-Q are related to the marked localisation of pain on the drawing, marking several areas make it difficult to determine which pain location the participants based their answers upon. This weakens the estimate of the test-retest reliability as the participant might refer to different localizations when answering the PD-Q at different time points.

The patient characteristics in the previous studies of the PD-Q was described to be similar to those included in the study of the Norwegian PD-Q, with average age between 48 and 57 years, predominantly women, and with symptom duration in average 8-12 years [Citation11,Citation14,Citation16–18,Citation20,Citation39]. In addition, similar inclusion- and exclusion criteria were used for the Norwegian PD-Q and the similar studies [Citation11,Citation16–18,Citation20,Citation39]. Our study included patients with a great variety of diagnosis and with long-lasting pain reflecting a broad spectrum of patients seeking physical treatment. This was in line with the Arabic [Citation16], English [Citation11], Dutch [Citation20], Hindi [Citation39] and Spanish [Citation18] studies. However, the PD-Q was originally developed and validated for patients with low back pain [Citation12]. The use of the questionnaire on a broader patient cohort, aiming to increases the generalisability of the questionnaire, will therefore require a thorough exploration of the PD-Q in terms of validity [Citation24].

Previous studies examining test-retest reliability of the PD-Q have all a low number of participants, ranging from 11 to 40 for the Japanese [Citation17], Spanish [Citation18] and Swedish [Citation19] study. Tampin et al. [Citation11] had the highest reported number of participants, 129 and 66 for the long- and short-term reliability, respectively. The studies of the Arabic [Citation16], Dutch [Citation20] and Hindi [Citation39] versions do not explicitly mention the number of participants. They only describe the overall number in the validation study. Except for the English [Citation11] version with a 60.5% response rate for PD-Q (post), this information was also not found in other studies. Our study had a response rate of 78%, while >60% is described as satisfactory [Citation24].

Missing answers and difficulties understanding the questions and information on the form indicates that the PD-Q is not optimal for use without follow-up information from health professionals. Tampin et al. [Citation11] have suggested to use an electronic version of the questionnaire to reduce the risk of missing answers. Such a version can ensure that it’s not possible to complete without answering all questions, thereby removing the issue of missing answers as seen in the German study [Citation14]. We can, however, not know whether the questions have been correctly understood. Future studies with a qualitative study design focussing on the participants understanding of each item and the questionnaire in total is also recommended to ensure applicability and validity of the PD-Q.

Limitations

The participants were asked to fill out the PD-Q a second time after 14 days and return it by mail. Some wrote the date on the form, but else we cannot be sure that the time interval for the individual participants was exact.

Future research

Content validity of the PD-Q should be examined with a qualitative design exploring interpretation of the specific items as well as understanding why some questions have a higher prevalence of missing answers, and lower reliability. The best cut-off points for classifying neuropathic pain as unlikely, ambiguous, and likely should also be examined.

Conclusion

Test-retest reliability of the total score of the Norwegian translation of the PD-Q is considered good, and in line with previous reliability studies of PD-Q in different languages. Single items were found with reasonable to substantial reliability, but it was realised that users of the questionnaire may need guidance when filling out the questionnaire the first time to avoid missing data and misunderstanding of questions. The screening of neuropathic pain in the Norwegian version has only moderate test-retest reliability which calls for exploring the best cut-off points for classifying the condition as unlikely, ambiguous, and likely neuropathic pain.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee (REK) (registration number 2018/911). The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki (as amended in 2013) and national regulations and institutional policies. Informed consent has been obtained from all participants in this study.

Author contributions

Both authors have accepted responsibility for the entire content of this manuscript and approved its submission.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Mitchell T, Beales D, Slater H, et al. Musculoskeletal clinical translation framework: from knowing to doing. Perth: Curtin University; 2017.

- Timmerman H, Wilder-Smith O, van Weel C, et al. Detecting the neuropathic pain component in the clinical setting: a study protocol for validation of screening instruments for the presence of a neuropathic pain component. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:94.

- IASP taxonomy: International Association for the Study of Pain; 2012 [updated 22.05.1228.07.19]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698&navItemNumber=576#Pain.

- Haanpää M, Treede R-D. Diagnosis and classification of neuropathic pain: IASP; 2010 [cited 2017 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsletterIssue.aspx?ItemNumber=2083.

- Doth A, Hansson P, Jensen MP, et al. The burden of neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of health utilities. Pain. 2010;149(2):338–344.

- Magrinelli F, Zanette G, Tamburin S. Neuropathic pain: diagnosis and treatment. Pract Neurol. 2013;13(5):292–307.

- Gilron I, Watson CPN, Cahill CM, et al. Neuropathic pain: a practical guide for the clinician. CMAJ. 2006;175(3):265–275.

- Haanpaa M, Attal N, Backonja M, et al. NeuPSIG guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment. Pain. 2011;152(1):14–27.

- Khan KAA, Jull GA. Grieve's modern musculoskeletal physiotherapy. 4th ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2015.

- Finnerup NB, Haroutounian S, Kamerman P, et al. Neuropathic pain: an updated grading system for research and clinical practice. Pain. 2016;157(8):1599–1606.

- Tampin B, Bohne T, Callan M, et al. Reliability of the english version of the painDETECT questionnaire. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33(4):741–748.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911–1920.

- Smith B, Torrance N. Epidemiology of neuropathic pain and its impact on quality of life. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16(3):191–198.

- Keller T, Freynhagen R, Tolle TR, et al. A retrospective analysis of the long-term test-retest stability of pain descriptors of the painDETECT questionnaire. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(2):343–349.

- Pfizer. Language versions of the PainDetect questionnaire [01.05.19]. Available from: https://www.pfizerpcoa.com/order-measures.

- Amani A-S, Shehu Y, Muhammad R, et al. Testing the validity and reliability of the arabic version of the painDETECT questionnaire in the assessment of neuropathic pain. PLOS One. 2018;13(4):e0194358.

- Matsubayashi Y, Takeshita K, Sumitani M, et al. Validity and reliability of the japanese version of the painDETECT questionnaire: a multicenter observational study. PLOS One. 2013;8(9):e68013.

- De Andrés J, Lopez-Alarcón MD, Pérez-Cajaraville J, et al. Cultural adaptation and validation of the painDETECT scale into Spanish. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(3):243–253.

- Hallström H, Norrbrink C, Hallstrom H. Screening tools for neuropathic pain: can they be of use in individuals with spinal cord injury? Pain. 2011;152(4):772–779.

- Timmerman H, Wolff AP, Bronkhorst EM, et al. Avoiding catch-22: validating the pain DETECT in a in a population of patients with chronic pain. BMC Neurol. 2018;18(1):91. DOI:10.1186/s12883-018-1094-4

- Timmerman H, Wolff AP, Schreyer T, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation to the Dutch language of the PainDETECT-Questionnaire. Pain Pract. 2013;13(3):206–214.

- Elias LA, Yilmaz Z, Smith JG, et al. PainDETECT: a suitable screening tool for neuropathic pain in patients with painful post-traumatic trigeminal nerve injuries? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;43(1):120–126.

- Tampin B, Briffa NK, Slater H, et al. Identification of neuropathic pain in patients with neck/upper limb pain: application of a grading system and screening tools. Pain. 2013;154(12):2813–2822.

- de Vet HCW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Measurement in medicine: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- Mokkink LB, Prinsen CA, Patrick DL, Vet HCd, et al. COSMIN study design checklist for Patient-reported outcome measurement instruments. Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics. Amsterdam Public Health research institute; 2019 [Revised July 2019; cited 2021 Aug 24]. https://www.cosmin.nl/wp-content/uploads/COSMIN-study-designing-checklist_final.pdf.

- Rampakakis E, Ste-Marie PA, Sampalis JS, et al. Real-life assessment of the validity of patient global impression of change in fibromyalgia. RMD Open. 2015;1(1):e000146. DOI:10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000146

- Jensen MP. The pain stethoscope: a clinician’s guide to measuring pain. Tarporley: Springer Healthcare Ltd.; 2011.

- Bennett MI, Attal N, Backonja MM, et al. Using screening tools to identify neuropathic pain. Pain. 2007;127(3):199–203.

- Koo TK, Li MY. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiroprac Med. 2016;15(2):155–163.

- Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85(3):257–268.

- The United States Pharmacopeial Convention. USP Medicare model guidelines V8.0; 2021 [Revised February 2020; cited 2021 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.usp.org/health-quality-safety/usp-medicare-model-guidelines.

- Pfizer. Neurontin. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website; 2021 [Revised December 2020; cited 2021 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/020235s064_020882s047_021129s046lbl.pdf.

- Pfizer. Lyrica. U.S. Food and Drug Administration website; 2021 [Revised May 2018; cited 2021 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021446s035,022488s013lbl.pdf.

- Tsang S, Royse CF, Terkawi AS. Guidelines for developing, translating, and validating a questionnaire in perioperative and pain medicine. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11(Suppl 1):S80–S89.

- Streiner D, Norman GR, Cairney J. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. New York: Oxford University Press; 2015.

- Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(8):931–936.

- Freynhagen R, Tolle TR, Gockel U, et al. The painDETECT project – far more than a screening tool on neuropathic pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(6):1033–1057.

- Woolf CJ. What is this thing called pain? J Clin Invest. 2010;120(11):3742–3744.

- Gudala K, Ghai B, Bansal D. Neuropathic pain assessment with the PainDETECT questionnaire: cross‐cultural adaptation and psychometric evaluation to Hindi. Pain Pract. 2017;17(8):1042–1049.