Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to examine perceptions of work readiness from Australian physiotherapy graduates and employers. Recent research has described four domains of work readiness: Interpersonal Capabilities, Practical Wisdom, Personal Attributes and Organisational Acumen. Methods: Responses regarding the challenges and facilitatory strategies during the transition from student to physiotherapist were collected using graduate and employer surveys and were thematically analysed using a qualitative, iterative approach. Responses were initially deductively themed using domains derived from prior research and further themes were identified inductively during analysis. Results: A total of 87 graduates and 174 employers participated. Thematic analysis supported the four existing domains of work readiness and an additional two themes (proposed domains) Profession Specific Knowledge and Skills and Professionally Relevant Experiences were identified. Overall, the six domains aligned amongst graduates and employers with nuanced differences. Graduates used an individual, short-term lens and employers with a team-based, long-term view. Conclusion: There was broad alignment between graduates and employers of challenges and faciliatory strategies within the six domains. The domains identified in this study provide a holistic view of work readiness and may be used as a framework to better prepare and support graduates, and to direct learning and development to enhance the transition into the healthcare workforce.

Introduction

The transition from student to working physiotherapist is challenging. Upon entering a rapidly changing modern healthcare system graduates must practice autonomously, taking on an increased responsibility for patient care [Citation1]. Physiotherapy graduates are expected to contribute as successful team members, advocating for their patients within complex healthcare systems and communicating effectively in dynamic multidisciplinary healthcare teams [Citation2]. Further, in order to continue meeting professional standards, graduates must engage in lifelong learning, and ongoing professional development [Citation3]. While university programmes are required to develop capabilities (knowledge, skills and attributes) required to meet the standards for registration [Citation4], the limited research exploring the challenges physiotherapy graduates face as they enter the workforce have found stress, complex decision making, increasing workload, decreasing support and a lack of confidence to be major factors contributing to feeling inadequately prepared for commencing work [Citation5–10]. These challenges possibly contribute to high levels of burnout and attrition seen amongst newly qualified physiotherapists [Citation11]. Therefore, understanding the domains of work readiness may be beneficial to facilitate successful transition from student to physiotherapist.

Measurement of work readiness is in its infancy. Four distinct but interrelated domains of work readiness, Interpersonal Capabilities, Practical Wisdom, Personal Attributes and Organisational Acumen, have been identified through validation of the Work Readiness Scale for Allied Health Professionals (WRS-AH32) [Citation12]. Briefly, Interpersonal Capabilities are defined as the ability to communicate with major stakeholders within the workplace and includes communication with multidisciplinary team members, patients and their carers. Practical Wisdom is the ability to make deliberate, effective and appropriate decisions within the workplace for both individual and common good. It includes capabilities such as managing complexity in patient care, and recognising scope and expertise of practice. This domain also encompasses the understanding of opportunities for future growth and development within one’s career given such individual development may improve healthcare of others [Citation13] and/or health systems. Personal Attributes are specific characteristics that an individual brings to the workplace that allow them to successfully navigate the challenges of a fast-paced and ever-changing healthcare landscape such as confidence, time management, managing mental health, stress, and work-life balance. Finally, Organisational Acumen is the ability to understand and operate in complex health systems. Full definitions of these domains can be found in . Using the WRS-AH32, in contrast to previous research, it was found that overall allied health and physiotherapy graduates perceive themselves to be work ready, with highest scores in the Practical Wisdom domain, and lowest in the Personal Attributes domain [Citation12,Citation14]. However, while shown to be a reliable scale, items within the WRS-AH32 account for only 38% of the total variance in work readiness [Citation12], suggesting there are other domains of work readiness not captured within this scale.

Table 1. Domain definitions from the WRS-AH32 (from Lawton et al. 2023 [Citation12]).

Therefore, this study explored the perceptions of graduate physiotherapists and employers regarding the challenges and supportive strategies during the transition from student to physiotherapist. The primary aim was to determine the domains of work readiness. Firstly, by confirming the alignment of identified challenges with the four domains of the WRS-AH32, and secondly identifying any other domains of work readiness. The secondary aims were to assess if the supportive strategies mapped to the domains, and to evaluate the alignment of graduates and employer perceptions.

Methods

Design

Two separate prospective, cross-sectional surveys (graduate and employer) were distributed nationally to potential participants collecting information regarding their perspectives on work readiness and transitioning into the workforce. Ethical approval was obtained from the Macquarie University Human Research Ethics Committee (ethics number 520211034632272 and 520211038032368, respectively).

Participation and recruitment

Physiotherapy graduates were invited to participate if they had completed their accredited entry-level physiotherapy degree in Australia, were registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Authority (AHPRA) and had worked for 6 weeks to 3 years. Employers were invited to participate if they had employed or supervised one or more physiotherapy graduates in the past three years. Participants were recruited for the survey by purposive and passive snowballing techniques to maximise the representation and quantity of responses [Citation16,Citation17].

Potential participants were identified through academic faculty colleagues of the research team, clinical partners of the participating higher education institutions, as well as searching publicly available directories and websites such as the Australian Physiotherapy Association’s ‘Find a Physio’ website, and job websites seeking graduate physiotherapists. Participation was promoted through advertisements with the Australian Physiotherapy Association, and social media sites frequented by physiotherapy graduates. Participation in the survey was voluntary, and anonymous [Citation12]. Once submitted, survey responses were unable to be excluded from the study due to anonymity.

Surveys

Both surveys were purpose built and hosted on Qualtrics (Provo, UT) licenced to Macquarie University. Each purpose-built survey included a combination of multiple-choice questions regarding demographic and work information and open-ended questions regarding challenges and facilitatory strategies during the transition from university to the workplace. Prior to distribution, surveys were piloted on nine graduates and two employers to ensure appropriateness, relevance, clarity of questions, and survey flow. Minor amendments were made based on comments prior to distribution and data collection. Both surveys included demographic data including age and gender, which state in Australia participants completed their degree, and which type of entry-level degree they had completed (such as Bachelors, Masters, or extended Masters). Current work information gathered included the number of years participants had worked, and the state, sector and setting of their current positions. Within the graduate survey, participants were asked to identify up to three challenges they faced during their transition to physiotherapist, and any strategies they perceive may have helped overcome each challenge identified. Employers were asked to identify up to three difficulties they believed new graduates faced, and up to three facilitators they have found helpful in managing new graduate physiotherapists. Online surveys were open between October 2021 to May 2022 to allow sufficient time and opportunity to complete the survey.

Data analysis

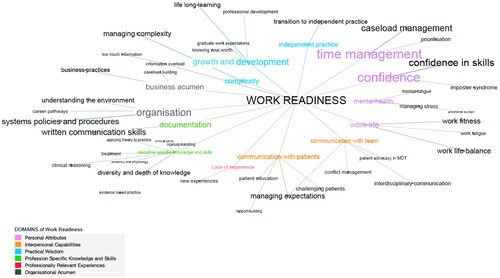

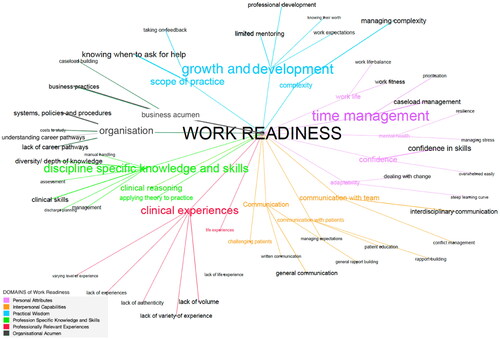

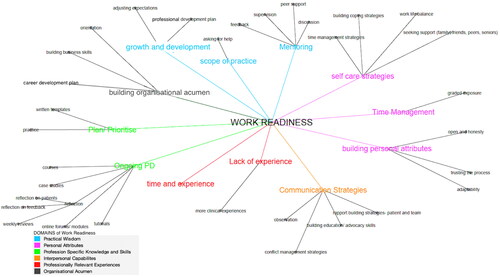

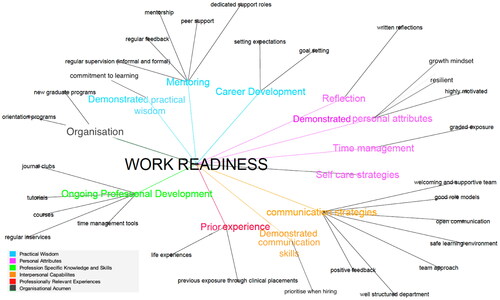

Both quantitative and qualitive analyses were undertaken. Descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations and ranges) were used to summarise the demographics of participant populations using IBM SPSS Statistics for Mac, version 27.0. Surveys that provided at least one challenge to work readiness were included in the qualitative analysis. A visual representation of the domains, identifying challenges (), and strategies () aided in the integration and analysis of responses between graduate and employer groups. Figures for analysis of graduate and employer challenges and strategies were created by Gephi 0.10.1.

Figure 1A. Graduate challenges in work readiness. Challenges (coloured by Domains and label weighted by number of times mentioned by participants) and examples (labels weighted by number of times mentioned by participants).

Figure 1B. Employer challenges in work readiness. Challenges (coloured by Domains and label weighted by number of times mentioned by participants) and examples (labels weighted by number of times mentioned by participants).

Figure 2A. Graduate strategies to overcome challenges in work readiness. Identified strategies (coloured by Domains) and examples.

Figure 2B. Employer strategies to overcome challenges in work readiness. Identified strategies (coloured by Domains) and examples.

An adaptation of Charmaz’s constructivist grounded theory [Citation18] was used in a qualitative, iterative approach using both deductive and inductive analysis. Open-ended questions regarding perceived barriers to work readiness identified by graduates and employers were initially analysed independently by three academic physiotherapy researchers (VL, CD and CC). At the time of the study, two researchers, CD and CC, were senior university academics with extensive education research and qualitative research experience respectively. Both VL and CD had content knowledge expertise and were involved with the development of the survey along with refinement of the WRS-AH32 scale and its derived domains. The third researcher, CC, was chosen to minimise any bias as he had not been involved in any prior development or research within the work readiness field. Each team member assigned codes to the open-ended responses. These codes were brought together in a meeting where they were deductively grouped into themes using the four domains of the WRS-AH32 (12) where appropriate. New domains were then inductively identified based on responses that did not fit into these four domains.

A final consensus meeting was held where deductive and inductive analyses were presented to an independent observer (VP), a senior academic physiotherapist with expertise in qualitative research and prior involvement in the refinement of the WRS-AH32. Themes using the domains from the WRS-AH32 were confirmed and resolution of the new themes, proposed as domains, were facilitated. Analysis of the responses within domains between graduates and employer participant groups was also conducted. In her role as observer, VP ensured data supported domains, and where divergences from alignment occurred between groups within domains.

Once the domains were established through analysis of the reported challenges, analysis of the strategies provided to overcome perceived challenges was undertaken. Responses were grouped by one team member (VL) to appropriate domains separately for graduates and employers, and then integrated. The grouping of strategies was discussed by members of the research team (VL, CD, CC and VP) during the final consensus meeting, and any differences or conflicts resolved. Analysis of alignment and nuanced differences of strategies were confirmed through iterative discussion. Once collated, a further investigation of strategies was conducted with consideration of those strategies that could be demonstrated during the employment process and those implemented once employed. This was discussed and finalised with members of the research team (VL, CD and VP).

Results

Participants

Of the 109 graduate surveys and 192 employer surveys submitted, 40 were excluded as no challenges were identified within the survey. A total of 87 physiotherapy graduates (80%) and 174 employers (91%) responded to the open-ended questions in each respective survey and were included in the analysis (). More than half the physiotherapy graduate respondents were female (62%) and working in the private sector (55%), and most states and territories of Australia were represented. The majority of responses were from New South Wales (70%), then Queensland (17%). Almost half of graduate respondents had completed a graduate entry masters extended degree (46%). Just over half the employer respondents were female (55%) with 50% working in the hospital setting. Employer respondents had worked for an average of 17 years (SD 10). Of those who had answered questions on their education qualifications, most had completed an entry-level bachelor degree in physiotherapy (). The majority of responses were from employers in New South Wales (77%), then Queensland (14%); however, most states and territories of Australia were represented.

Table 2. Summary of participant characteristics.

Qualitative analysis of challenges and facilitatory strategies

Of the 87 graduate physiotherapist surveys included in the analysis, most (86%) provided three unique challenges, with a total of 239 unique challenges and 234 strategies analysed. Of the 174 employer participants whose survey responses were analysed, 161 (94%) provided three unique challenges, with a total of 502 unique challenges and 493 strategies analysed.

Through deductive analysis, challenges reported by graduate physiotherapists and employers confirmed themes aligned to the four domains of the WRS-AH32. Inductive analyses identified two further themes (proposed domains) which were interpreted as impacting graduate work readiness. Analysis of open-ended survey responses identified that the challenges graduates identified during transition into the workforce, and the associated strategies to overcome these challenges, could be encompassed within the six broad domains: Interpersonal Capabilities, Practical Wisdom, Personal Attributes, Organisational Acumen, Profession Specific Knowledge and Skills, and Professionally Relevant Experiences. Examples of Illustrated quotes in each domain can be seen in .

Table 3. Perceived challenges: Themes and quotes.

Theme 1: (WRS-AH32 domain 1) Interpersonal capabilities

Responses grouped within this theme fit within the first domain in the WRS-AH32. Alignment in responses was noted between graduates and employers, and sectors (public and private). Communication with patients, such as rapport building and managing patient expectations were identified as challenges and was especially noted with more complex patients and situations. Communication with the wider multidisciplinary team was also mentioned, particularly conflict management and patient advocacy. Employers noted the lack of understanding of new graduates in the differing roles of multidisciplinary team (MDT) members, viewing this challenge from an organisational perspective.

Suggested strategies to overcome these challenges generally aligned between graduates and employers. Graduates provided strategies for immediate improvement of performance, including practicing different communication styles, observing other practitioners and building conflict management strategies. Employers focused holistically on the environment of the team, noting successful strategies were aimed towards positive team culture, supportive department structures, and safe learning environments. Furthermore, employers preferenced employing graduates who demonstrated some interpersonal capabilities such as strong communication skills.

Theme 2: (WRS-AH32 domain 2) Practical wisdom

Within this theme, both graduates and employers noted the difficulty of managing complexity and knowing when to ask for help. Both graduates and employers also reported that understanding opportunities for growth and development was a major challenge, however, this was viewed from a slightly different lens by graduates and employers. The graduates’ focus was on the individual, stating an increase in expectations of themselves and from others within the healthcare team in making decisions for their patients, and at times for themselves. These challenges were noted in both public sector and private sector graduates. Employers viewed these opportunities more holistically, noting the difference between life as a student, where the focus is on their own learning, to becoming a professional where the primary focus is on the patient. Employers reported graduate expectations of themselves and their roles as new graduates were often unrealistic. Public sector graduate and employer views matched those in the private sector.

Suggested strategies to overcome these barriers were broadly aligned between graduates and employers with some nuanced differences. Both graduates and employers suggested mentorship as a key strategy to overcome challenges within this domain. Graduates were focused on strategies that were personalised, specific and could be implemented in the near future, including asking for help, self-reflection strategies, and managing immediate expectations. Employers applied a broader, future focused lens, with strategies such as establishing expectations and goal setting, and regular and ongoing supervision and feedback sessions. Employers also sought out graduates already demonstrating some capability within this domain such as willingness to ask questions and commitment to self directed learning.

Theme 3: (WRS-AH32 domain 3) Personal attributes

Personal Attributes was the third domain within the WRS-AH32, and responses aligned closely between graduates and employers. Challenges such as time management, workload management and prioritisation, along with the completion of both clinical and non-clinical tasks efficiently were reported. The same themes were noted regardless of the sector in which respondents worked. Other common responses between graduates and employers included work “fitness” and the ability to manage full time work both physically and mentally. While both graduates and employers noted confidence to be the primary decision maker as a challenge, graduates spoke of “imposter syndrome” and a lack of confidence as the challenge to being a primary decision maker, whereas employers identified graduates varied between under confident and overconfident in their practice. Graduates also reported an increase in mental fatigue and stress associated with the transition to full time work, balancing both work and life. Employers noted graduates were more rigid in their approach to work roles, and there was a need to master adaptability and flexibility required to work successfully and stay resilient within the healthcare system.

Strategies suggested to overcome challenges within this domain were thematically aligned. Graduate strategies were specific, immediate and individualised, whereas employers considered a more holistic employment strategy. Graduates noted relaxation and coping strategies, seeking support from family and friends, exercise, sleep and developing templates for time management tools. Employers however focused more on preferencing candidates during the employment process with demonstrated personal attributes for work such as high motivation, resilience, and growth mindset. Some strategies noted to improve time management such as graded exposure were more developmental in nature, and “self-care strategies” was noted, however minimal details as to what these entailed were provided in survey responses.

Theme 4: (WRS-AH32 domain 4) Organisational acumen

Organisational acumen contained identified responses such as understanding specific and contextual rules and regulations, from administrative processes to complex procedures such as navigating national funding agencies. Business acumen and understanding organisations were identified by both graduates and employers as challenges during the transition to work. Respondents working in the private sector reported challenges with caseload building and patient retention, and in understanding the commercial realities of business. Graduates and employers in both sectors identified further challenges in understanding the environment of the organisation they worked in, such as systems, policies and procedures, and healthcare structures, roles and responsibilities.

Suggested strategies to overcome this challenge aligned closely between graduates and employers regardless of sector. Clear orientation programs and building and understanding of processes and procedures were recommended.

Theme 5: (proposed domain) Profession specific knowledge and skills

This theme and proposed domain was defined as the set of discipline specific knowledge and skills required to practice as a health professional. It includes depth and breadth of knowledge of theoretical concepts and principles relevant to physiotherapy practice, and is underpinned by knowledge of anatomy, physiology and pathology related to human health and function. Profession specific skills include assessment and management of common conditions encompassing musculoskeletal, cardiorespiratory, neurological and other body systems, with patients across the lifespan.

Graduates and employers in both sectors reported the depth and breadth of discipline-specific knowledge and skills required for different areas of practice was a challenge to successfully transitioning to practice. Graduate physiotherapists nominated documentation and report writing as a challenge when commencing work as a physiotherapist. Conversely, employers spoke more holistically of applying theory to real-world scenarios and the ability to individualise management plans through the identification of patient-centred risks, needs and goals.

Strategies mentioned by graduates remained focused on the immediate future and were targeted more as pragmatic tasks that could improve readiness within this domain including using templates, reflection, and ongoing professional development to fill gaps in knowledge and skills. Employers focused on broad strategies that were aligned with the challenges they described. These strategies contribute to the sustainability and improvement of the team as a whole, including journal clubs, complex case analysis, and regular inservices for graduates.

Theme 6: (proposed domain) Professionally relevant experiences

This theme and proposed domain were defined as activities that influence a student’s professional practice to enhance successful transition into the workplace. In the context of work readiness, professionally relevant experiences include clinical experiences gained within university programs but can also include any activities known to contribute to the perception of work readiness. For example, extracurricular paid and unpaid roles and experiences such as teaching sports or music, leadership roles within university societies, and part-time allied health assistant positions [Citation19]. Co-curricular activities that may contribute to this domain include Professional Development evenings organised by student or professional bodies such as the Australian Physiotherapy Association.

Themes within this domain focused mainly on a lack of experience as they transitioned to areas of practice that had not been encountered as a student physiotherapist. While both graduates and employers mentioned discrete specialised areas of physiotherapy practice, such as Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and private practice, graduates focused on discrete knowledge, skills, and conditions they had not experienced as a student. Employers additionally focused on lack of general work experience and life experience that would contribute to work readiness. These views were the same in graduates and employers working in the public and private sector.

Strategies to overcome these challenges aligned between graduates and employers. Participants reported that a larger variety of clinical placements during university studies would aid in improving experience and skills when commencing work. However, there were subtle differences between graduates and employers that aligned with the challenges they presented. Graduates focused on specific experiences, such as ICU specific courses, and discharge planning, while employers spoke more broadly, prioritising the employment of graduates with both specific clinical experiences, and general life experience.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine the domains of work readiness through the exploration of challenges faced by graduate physiotherapists as they transition into the workforce. The main finding of this study is the identification of six themes, proposed as domains of work readiness, that encompassed survey responses of graduates and employers. Four domains aligned with the established domains of WRS-AH32 [Citation12], and two further domains were identified during the qualitative analysis process. Overall, there was an alignment of responses within each domain between graduates and employers, however each group provided slightly nuanced differences with challenges and strategies seen from different lenses. Graduates viewed challenges from an individual lens, with strategies targeting immediate improvement of their performance as a professional. Employers took a long-term approach, seeing challenges more holistically, and strategies to target the sustainability of their employees, and of the profession. However, employers also reported preferencing graduates demonstrating greater work readiness at the point of recruitment.

This study captured the challenges to work readiness within an Australian setting, in six broad domains, which were context independent. Graduates and employers found similar challenges to work readiness regardless of the setting or sector in which they worked. The challenges found within these domains such as time management, increased complexity, communication with patients and team members, and understanding organisational policies and procedures, were similar to previous research in acute, public settings [Citation5–7] and in private practice settings [Citation9,Citation10] both within Australia and internationally. However, other challenges during work transition found in this study were novel, with broader issues such as work fitness and professional development. Many challenges found within this study also fit within the four domains identified by the recently validated WRS-AH32 [Citation12], such as communication and confidence. However, other challenges such as lack of experience and clinical skills fit within two new domains identified during analysis. The results of this study therefore extend on the four domains of work readiness in the WRS-AH32 [Citation12].

Strategies to improve work readiness were more context specific and considered as a shared responsibility of all stakeholders involved in the transition from student to physiotherapist. Strategies provided in this study by graduates were more individualised and dependant on their own experiences, suggesting that there is not a ‘one size fits all’ strategy. However commonality was found between graduates and employers, and all of the strategies provided by both groups mapped to the six identified domains. Employers also recognised the need to provide strategies for their employees, however these strategies remained more holistic in nature. The framework of six domains established by this study allows for employers to identify specific areas in which their employees might require more support, and for graduates to self-assess their perceptions of work readiness and develop individual strategies within each of the domains, both as a physiotherapy student but also as a graduate transitioning into the workforce.

Work readiness is an expected outcome of any university degree [Citation20–22], and therefore the onus of physiotherapy programs is to incorporate the development of capabilities within these domains that enhance work readiness within its curriculum. Interestingly, a strategy noted by employers was to employ those with demonstrated capabilities within the domains of Interpersonal capabilities, Practical Wisdom, Personal Attributes, and Professionally Relevant Experiences, suggesting that industry believe these should be developed pre-employment. This increases the importance of physiotherapy students, graduates, and university programmes to identify, support and develop aspects of these domains during university studies. University curriculum must prioritise the development of a variety of communication skills, alongside fostering the passion, drive and commitment to learning of its graduates, and the development of personal attributes for work such as resilience, self-care and stress management. This is particularly important as graduates perceive themselves least work ready within the Personal Attributes domain [Citation12], suggesting that more needs to be done by universities in this area. Finally, university clinical programs must continue to partner with willing industry partners to provide quality clinical placements that provide a variety of real world experience. A framework of work readiness also allows for education providers to map curriculum to these domains, to identify strengths and opportunities where knowledge, skills and attributes to enhance work readiness could be included.

This thematic analysis was completed on survey responses from graduates and employers from a range of settings, in both public and private sectors, and represented most states and territories across Australia. While many of the respondents were from one state, and/or graduated from a Doctor of Physiotherapy degree, the challenges and strategies found within this study align with previous research in health professional graduate work readiness [Citation9,Citation12,Citation23]. Importantly, a robust thematic analysis was performed, and data saturation was achieved as all challenges and strategies collected from participants fit within the six domains identified in this study. The surveys were distributed during the second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in Australia in 2021. The rapid increase in hospitalisations, shut down of many small businesses such as private practices, and subsequent strain on healthcare workers contributed to the increase in mental health concerns of both Australian healthcare workers [Citation24] and students [Citation25] and may have influenced the responses in the survey at this time. Limitations were noted with survey methodology, such as the inability to elaborate or clarify statements provided within the survey. However, the anonymity of the surveys may have provided the opportunity for participants to be honest with their responses. Moreover, the fact that Australia offers a range of undergraduate and postgraduate entry-level programmes and all were represented in our sample may enhance the generalisability of our findings.

Quantifying and measuring work readiness may aid in identifying and developing the work readiness of health professions graduates. Previous research through the validation of the WRS-AH32 identified four domains but had only accounted for 38% of the variance explained. The identification of the two additional domains in this study could potentially increase the variance explained within the work readiness model. An extension of prior work on the WRS-AH32 is recommended, where further items within these two domains could be developed and added prior to a revalidation of the scale. Alternatively, the influence of these two domains within work readiness could be assessed in other ways. Profession-specific knowledge and skills, and professionally relevant experiences are both assured within university curriculum to meet professional standards to the threshold level required for registration and further regulated through external accreditation processes by health profession authorities. Measures of graduate outcomes such as weighted average marks (WAM) across the entire program may quantify the Profession Specific Knowledge and Skills domain, and the WAM across clinical placement units may provide a measure of Professionally Relevant Experiences domain. However, the impact of co-curricular and extra-curricular activities on the quantification of Professionally Relevant Experiences warrants further development and investigation. The extent to which university curriculum develops the knowledge, skills and attributes within these six work readiness domains to prepare their graduates for work is also warranted.

The results of this current study establish six domains that encompass work readiness in graduate physiotherapists. Challenges reported within each domain were universal and broadly aligned between employers and graduates, however strategies to overcome challenges remain individualised and dependant on the context. The six domains provide a framework in which all stakeholders can evaluate work readiness, and develop targeted strategies for development of the knowledge, skills and attributes of graduates that support the transition from university to the workforce.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Malau-Aduli BS, Jones K, Alele F, et al. Readiness to enter the workforce: perceptions of health professions students at a regional Australian university. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03120-4.

- World Physiotherapy. Policy statement: relationship with other health professionals. 2023. London, UK: World Physiotherapy. Available at: https://world.physio/policy/ps--otherprofessionals

- Physiotherapy Boards of Australia and Aotearoa NewZealand. Physiotherapy Practice Thresholds in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. 2015. Available at: https://www.physioboard.org.nz/sites/default/files/PhysiotherapyPractice%20Thresholds3.5.16.pdf.

- Australian Physiotherapy Council. Accreditation Standard for entry-level physiotherapy practitioner programs. December 2016. Available at: https://cdn.physiocouncil.com.au/assets/volumes/downloads/Accreditation-Standard.pdf.

- Phan A, Tan S, Martin R, et al. Exploring new-graduate physiotherapists’ preparedness for, and experiences working within, Australian acute hospital settings. Physiother Theory Pract. 2022;39(9):1918–1928.

- Stoikov S, Maxwell L, Butler J, et al. The transition from physiotherapy student to new graduate: are they prepared? Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;38(1):101–111. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2020.1744206.

- Miller PA, Solomon P, Giacomini M, et al. Experiences of novice physiotherapists adapting to their role in acute care hospitals. Physiother Can. 2005;57(02):145. doi: 10.2310/6640.2005.00021.

- Lau B, Skinner EH, Lo K, et al. Experiences of physical therapists working in the acute hospital setting: systematic review. Phys Ther. 2016;96(9):1317–1332. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20150261.

- Wells C, Olson R, Bialocerkowski A, et al. Work-Readiness of new graduate physical therapists for private practice in Australia: academic faculty, employer, and graduate perspectives. Phys Ther. 2021;101(6):1. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzab078.

- Solomon P, Miller PA. Qualitative study of novice physical therapists’ experiences in private practice. Physiotherapy Canada. 2005;57(3):190–198. doi: 10.3138/ptc.57.3.190.

- Scutter S, Goold M. Burnout in recently qualified physiotherapists in South Australia. Aust J Physiother. 1995;41(2):115–118. doi: 10.1016/S0004-9514(14)60425-6.

- Lawton V, Ilhan E, Pacey V, et al. A work readiness scale for allied health graduates. The Int J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2023;22(1):1–9.

- Sholl S, Ajjawi R, Allbutt H, et al. Balancing health care education and patient care in the UK workplace: a realist synthesis. Med Educ. 2017;51(8):787–801. doi: 10.1111/medu.13290.

- Lawton V, Pacey V, Jones TM, et al. The factors affecting work readiness during transition from university student to physiotherapist in Australia. HESWBL. 2024; Jan 5; Vol. ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1108/HESWBL-10-2023-0287.

- University of Florida. Team titles: Organisational acumen. Available from: https://teams-titles.hr.ufl.edu/job-competency/organizational-acumen/#:∼:text=**%20%E2%80%93%20TEAMS%20Titles-,Organizational%20Acumen**,commitment%20to%20the%20organizational%20mission. [AQ]

- Kitto SC, Chesters J, Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust. 2008;188(4):243–246. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01595.x.

- Sargeant J. Qualitative research part II: participants, analysis, and quality assurance. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(1):1–3. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-11-00307.1.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2006. SAGE Publications, London.

- Muldoon R. Recognizing the enhancement of graduate attributes and employability through part-time work while at university. Active Learning High Educ. 2009;10(3):237–252. doi: 10.1177/1469787409343189.

- Cake M, Bell M, Mossop L, et al. Employability as sustainable balance of stakeholder expectations – towards a model for the health professions. High Educ Res Develop. 2021;41(4):1028–1043. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2021.1891025.

- Speight S, Lackovic N, Cooker L. The contested curriculum: academic learning and employability in higher education. Tertiary Educ Manage. 2013;19(2):112–126. doi: 10.1080/13583883.2012.756058.

- Yorke M. Work-Engaged learning: towards a paradigm shift in assessment. Qual High Educ. 2011;17(1):117–130. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2011.554316.

- Opoku EN, Jacobs-Nzuzi Khuabi L-A, Van NiekerkL. Exploring the factors that affect new graduates’ transition from students to health professionals: an Integrative review. BMC Medical Education 2021;21(1):558. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02978-0.

- Smallwood N, Pascoe A, Karimi L, et al. Occupational disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic and their association with healthcare workers’ mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9263. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18179263.

- Koelen JA, Mansueto AC, Finnemann A, et al. COVID-19 and mental health among at-risk university students: a prospective study into risk and protective factors. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2022;31(1):e1901. n/a. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1901.