Abstract

Purpose

Vulvodynia is considered to be a common cause of sexual pain in women of reproductive age and has a significant negative impact on their psycho-sexual health and quality of life. This study aimed to investigate the felt and known experience of living with provoked vulvodynia (PVD) in a group of women in Sweden and to explore the support, information, and treatment perceived to be important based on experienced symptoms.

Methods

Ten women recruited by staff, from the vulva clinic at two hospitals in Sweden, participated in individual interviews. The results were analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

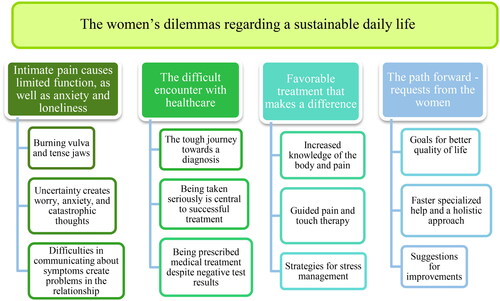

The analysis resulted in the overarching theme ‘The women’s dilemmas regarding a sustainable daily life’. This theme is based on the difficulties the women experienced in being listened to and getting information and treatment to have the quality of life they want. Most important was understanding their own body, understanding the purpose of the treatment, and getting manual guidance to break the fear of pain.

Conclusion

The results give a detailed picture of women’s experiences of PVD and delineate components of treatment perceived as important. This interview study is significant for healthcare professionals involved as the knowledge can contribute to faster diagnosis and better patient-specific treatment. The study may also guide future healthcare-related political decisions and the patient flow for these patients.

Introduction

Vulvodynia is considered to be a common cause of sexual pain in women of reproductive age [Citation1]. The pain is localised to the mucous membrane around the opening of the vagina and touch triggers an intense burning pain. The current classification of vulvodynia was established in 2015 and involves pain in the vulva for at least 3 months without any identifiable cause [Citation2]. Provoked vulvodynia (PVD) was previously referred to as ‘vulvar vestibulitis syndrome’ because it was considered an inflammatory reaction in the mucous membrane [Citation3]. During the 2000s, this was questioned, leading to a need to change the definition [Citation2]. Continuing further, the classification of vulvodynia is based on the description of symptoms [Citation4]. PVD occurs upon provocation, i.e. during intercourse or when an object is inserted into the vagina, while unprovoked vulvodynia occurs spontaneously. A combination of these conditions can also exist. Vulvodynia can also be classified as ‘primary’ or ‘secondary’ depending on when the symptoms occur [Citation2,Citation4,Citation5]. Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (GPPPD), previously termed dyspareunia and/or vaginismus first debuted in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013. The definition of GPPPD differs slightly from vulvodynia as it includes marked fear and muscle tension specifically involved in intercourse [Citation6].

The diagnosis is made based on the patient’s medical history and a gynecological examination, is performed to exclude medical causes for the pain. The causes of vulvodynia are not clear, but the condition is likely due to a combination of physiological and psychological factors [Citation7].

Several studies [Citation1,Citation8–11] report an increased tendency towards dysfunctional cognitive, emotional pain behaviour including avoidance patterns, such as fear of movement, hypervigilance, catastrophic thinking, and low self-esteem.

Vulvodynia affects women of all ages, regardless of ethnicity and reproductive stage. The prevalence of sexual pain is higher among younger women; in a Swedish study, sexual pain in a young, non-clinical population was reported to be as high as 29% [Citation12]. The typical patient is a woman in a stable relationship who has had sexual pain for several years and has visited several healthcare providers, such as a general practitioner, gynaecologist, dermatologist, and urologist, before finally receiving the correct diagnosis [Citation13]. Even when the diagnosis is established, it is a challenge for specialist healthcare to rehabilitate the condition. Vulvodynia has a significant negative impact on the patient’s psycho-sexual health and quality of life.

Multidisciplinary treatment is recommended for women with vulvodynia as the nature of the condition is complex and the evidence for a certain treatment modality is poor [Citation4,Citation13]. There is some evidence that combination physiotherapy can significantly reduce sexual pain and improve sexual function [Citation14]. Combination physiotherapy includes manual treatment, such as vulvar desensitisation, pelvic floor muscle stretching, myofascial release, conjunctive tissue manipulation, and neuromuscular re-education, pain education, pelvic floor muscle training, and relaxation. This is more effective than just a lubrication regimen with xylocaine ointment or similar [Citation14]. The complexities of pain sensation require research beyond the benefits and harms of an intervention as demonstrated by clinical trials. The evidence supporting the current regimen is derived from quantitative research, while qualitative research is needed to get a deeper picture of the patient group’s experiences, beliefs, and priorities for healthcare including both primary care and specialised care [Citation10].

LePage et al. [Citation15], examined the needs of eight women with PVD in Canada. The patient-focused needs assessment revealed that the women required better-educated doctors and desired treatment in the form of multidisciplinary teams, preferably in one location. A study by Ayling et al. [Citation16], investigated women’s subjective experience of vulvodynia within the context of a heterosexual relation. The article highlights how heterosexual norms impact Australian women with PVD. Danielsen et al. [Citation1] provided somatocognitive physiotherapy to six Scandinavian women with PVD and examined their experience of the therapy. The results indicate that the method helped the women view their pelvic region as part of their body, providing a sense of wholeness. A recent qualitative study [Citation17] was conducted on 14 Swedish women with vulvodynia regarding their experiences and perceptions of physiotherapy. The women found that physical therapy treatment allows reconnecting with the body and vulva in a new way and helps manage pain and muscle tension [Citation17].

There are few qualitative studies, investigating women’s experience of PVD and their experience of healthcare. The results of this study can increase the knowledge about how the healthcare chain can best assist the women.

This study aimed to investigate the felt and known experience of living with PVD in a group of women in Sweden and to explore the support, information, and healthcare perceived to be important based on experienced symptoms.

Methods

Design

To meet the aim of the study, a qualitative method with an inductive approach was chosen to gain deeper insight into participants’ individual experiences and analysing participants narratives in an open way searching for patterns [Citation18–21]. Individual interviews were conducted with ten women to investigate the experience of PVD. The results were analysed using qualitative content analysis [Citation19–21].

Participants

Convenience sampling was used. Recruited participants with PVD, available at a given time and willingness to participate in the study, were asked by staff from the vulva clinic at two hospitals in Sweden. The purpose of recruiting from different institutions was to consider that team treatment may differ between hospitals. The number of potential participants who were approached about, but not interested in, participating in the study is not known. All participants who showed an interest participated in the study and none chose to discontinue during the study.

Inclusion criteria were: women with a diagnosis of PVD. Exclusion criteria were: women with serious mental illness, malignancy, pregnancy or childbirth in the last 12 months, drug abuse, previous treatment by the researcher (J.H.), surgery in the pelvic region in the last 12 months, or a botulinum toxin (Botox) injection in the pelvic region in the last 4 months.

Data collection and procedure

Patients who met the inclusion criteria were invited orally to participate, during a visit to one of the clinics. Interested patients received a letter with information about the study and contact information to the researcher (J.H.). It was difficult to recruit participants when the onus was on the participant herself to contact the researcher (J.H.), which is why about half of the participants were instead asked if it was okay to be contacted by the researcher (J.H.). The interviews were conducted digitally via Microsoft Teams (Microsoft, Seattle, WA, USA) and recorded on two different voice recording apps on iPhone (Dictaphone App—Dorada Software Ltd and Voice Recorder—iTunes Apple software). Face-to-face sessions were not possible due to the ongoing pandemic. The interviews were held between 1 March and 1 July 2022, lasted 45–60 min, and were conducted by the first author (J.H.). The first author (J.H.) has several years of experience as a physiotherapist treating women with vulvodynia. The author (J.H.) had no prior relationship with the participants and was not involved in any treatment of the participants before, during, or after the interviews. The second author (R.S.) is a physiotherapist and researcher with experience in pain rehabilitation.

After an initial phone call or email to confirm participation and verify that the participant met the inclusion criteria, a time for the interview was scheduled via Teams. The participants received a consent form by post, along with questions about background information and a prepaid envelope to return the signed consent form.

The interviews were conducted using a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended and follow-up questions to achieve in-depth knowledge about the women’s experience of living with PVD. The interview questions included experiences of the healthcare process and requests for treatment based on perceived needs. Participants were asked about their opinion about what could be improved, as well as about aspects they needed help with most, and about their needs to achieve set goals. The interview guide was emailed to the participants before the interview to prepare them as best as possible. To ensure their relevance and appropriateness, several members of a vulva team at another hospital in southern Sweden were asked to give feedback on the interview questions [Citation22]. Also, pilot testing was conducted with a potential participant in the study. This pilot interview has not been included in the analysis of the study.

Data analysis

The interview material was analysed using qualitative content analysis [Citation19–21]. The interviews were recorded digitally, and transcription was done using the NCH Express Scribe Transcription Software Pro v 10.13 transcription software, Canberra, Australia. Data was analysed and interpreted using an inductive approach, which meant that the material was analysed without preconceptions [Citation18]. The analysis started with repeated readings of the material to get a sense of its entirety and content. After reading and listening to the interviews, meaning units were identified and condensed to shorten the content but maintain the essence. The condensed units were coded and then grouped and abstracted into categories and sub-categories by their commonalities on a manifest level. Further interpretation and abstraction resulted in a theme that exposes the latent content in the material. Quotations clarified and confirmed the findings [Citation19–21]. All steps of the analysis process were managed manually. For an example of the analysis process, see . To ensure dependability, the authors coded the material separately, compared their results, and then discussed the differences until a consensus was reached. Categories and sub-categories were discussed, then adjusted and developed separately, and the final versions were settled through discussion until consensus.

Table 1. Example of a meaning unit, condensed meaning unit, and code.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the Swedish Ethical Review Authority, Dnr 2021-06270-01, and written consent forms were obtained from all participants before the study.

Results

Ten women with PVD were included. Their average age was 30.4 years (range 27–39 years). They had had symptoms for an average of 7.3 years (3–20 years) and the average length of time to diagnosis was 5.2 years (1–19 years).

The analysis resulted in four categories, twelve subcategories, and an overarching theme (see ). The categories, subcategories, and themes, each supported by quotes, are presented below. Quotes are marked with the participant’s number. Based on the categories and subcategories, the theme ‘The women’s dilemmas regarding a sustainable daily life’ was formulated. The theme is based on the women’s stories of how they had unsuccessfully sought healthcare for years before finally ending up with the ‘right treatment’ and how they considered knowledge of their body and training in pain management important and helpful. The women expressed the importance of receiving support from someone who could answer their questions about how to behave and who could relate to the pain. In this study, it was primarily a physiotherapist who offered support and treatment to the women. Some women received treatment from both a physiotherapist and a psychologist concurrently. They were very satisfied with their treatment and felt strong support. Those who occasionally saw the physiotherapist in a group context did not experience such strong support. They requested to meet more healthcare professionals in the team and also asked to meet the physiotherapist individually.

Intimate pain causes limited function, as well as anxiety and loneliness

It became clear that the physical symptoms created psychological symptoms and that physical and psychological symptoms together negatively impacted the perceived quality of life on several levels.

Burning vulva and tense jaws

The participants described a wide range of coexisting physical symptoms. Common to all of them were increased muscle tension in the pelvis and pain on touching the genitals, particularly inside, and at the opening of, the vagina. The pain was often described as stinging, burning, and stabbing. Increased muscle tension in other parts of the body was common, particularly in the jaws and neck, as well as the shoulders. Some participants experienced needing to urinate more often and burning when urinating without a diagnosis of urinary tract infection. Many felt they had cracks in the vaginal opening, and these in turn led to recurrent fungal infections.

Uncertainty creates worry, anxiety, and catastrophic thoughts

The participants often talked about feelings of sadness, despair, and uncertainty. All the participants described a high degree of stress. The stress was caused by catastrophic thoughts, such as fear and worry about what could be causing the pain but also what it meant for the future, e.g. the possibility of having or staying in a relationship, having children, etc. The stress was exacerbated when healthcare professionals could not explain or help them understand the symptoms. They were uncertain whether the pain would get worse if they provoked it, which is why they avoided things that felt uncomfortable. The uncertainty about what was causing the pain led the participants into a circle of avoidance behaviour.

Just getting help with it, no matter how difficult it is. Confronting the pain because you don’t do that. You shut off. Because I know that. The physiotherapist asked me to draw myself the first time. I came back and I had only drawn my upper body. Participant #4

Many talked about how their symptoms had worsened because it had taken several years to get help from someone who could provide information about the pain. They described how difficult rehabilitation was when they had avoided provoking the pain for so long.

Uncertainty plays a role, but also avoiding touching the genitals. If you never put anything inside your vagina for many years, you become very inexperienced. It is difficult to know what to feel and not feel and the only memory you have is associated with pain. #3

Several participants even expressed fear of failure: Despite being advised to challenge the pain through touch, they avoided doing so because of fear of failing and thus took a step back in the rehabilitation process. For some, the fear was about becoming tense and anxious in intimate relationships, rather than provoking pain.

Difficulties in communicating about symptoms create problems in the relationship

The participants described difficulties initiating, maintaining, or being in a relationship. Those in a relationship often experienced a sense of guilt towards their partner that they were not delivering sexually.

I have the world’s best partner; we’ve been together for 11 years. He has been with me the whole time on this journey but at the same time, there’s always that sense of guilt that you can’t give or want to give the sexual part of the relationship. Which is also quite stressful to think about. Because it feels like you’re underperforming in the relationship. And I’ve noticed that it plagues me a lot. #2

Many described difficulties with boundary setting with their partner or potential partner. These were likely rooted in the fact that they did not know their bodies, their sexual needs, and their desires. Those who did not have a stable partner often had anxiety about explaining their problem with painful intercourse to a potential new partner. Those in long-term relationships where intercourse had once been problem-free felt sadness that their sex life had changed. Explaining their problems to their partner was difficult. The importance of a partner who was involved in the rehabilitation process and attended sessions was emphasised here.

He had a hard time understanding. He thought he would hurt me when we did those exercises. She [the physiotherapist] explained how it worked and that it could not get worse if you did this or that. Then he probably became less afraid as well. #9

The difficult encounter with healthcare

It became clear from the women’s stories that healthcare professionals, especially physicians, do not have sufficient knowledge about vulvodynia. They described the treatment they had received, in primary care, as very poor, characterised by mistrust and nonchalance.

The tough journey towards a diagnosis

All participants expressed that primary care professionals even gynaecologists, lack knowledge about the diagnosis of PVD and therefore are unable to make the correct diagnosis and take the necessary measures. They related how this had led to anxiety and burnout syndrome, sometimes even resulting in sick leave.

My energy ran out and I felt mentally exhausted by this. It feels pointless to go to a gynecologist when it doesn’t help anyway. I became anxious about seeking help in the end, so I gave up and let it go. #1

The participants’ quality of life was greatly affected, as was the relationship with their partner, and their studies and work. Hopes of getting help from a gynaecologist turned into disappointment and resignation as in some cases even the ‘specialist’ did not know what their problem was.

It needs to be taken more seriously and not just thought of as a fungal infection, urinary tract infection, or sexually transmitted disease. I would have appreciated if they had thought outside the box and asked questions and had done a thorough examination. #2

Throughout the interviews, the experience was that it was very difficult to get a referral to specialist care. It was the quest to find the right physician, someone who listened and took their problems seriously, which led to so-called ‘doctor shopping’. The participants told how not getting the ‘right’ help for a long time had negatively affected their mental well-being and quality of life.

Being taken seriously is central to successful treatment

The interviews revealed that the interaction in healthcare played a significant role in the development of pain. The most important thing was to be listened to and taken seriously. The participants described how devastating it is not to be believed or to be taken seriously. How lonely it feels when the physician says nothing is wrong despite the feeling that something is wrong. There were many descriptions of gynaecologists responding with ‘We all have our worries’ #8 or ‘He’s probably just too big for you’ #5.

Being prescribed medical treatment despite negative test results

All participants said that physicians often focused on taking samples and treating fungal or other conditions and lacked a holistic approach. The most common experience by far was being prescribed antifungal medication despite negative test results. This happened first at the youth clinic, where the participant received one or two antifungal treatments; later, further attempts at antifungal treatment were made at the specialist clinic, despite uncertain fungal test results. After this, care ended for most participants, and they had to continue searching for help themselves.

This isn’t unusual. I feel like because there are quite a few people who suffer from it … you should be able to understand, like, that if you don’t find anything in the samples… no, but then maybe you shouldn’t press a lot of medication on me; maybe there’s something else that you need to start working on. #8

The participants reported that, once they were in specialist care, the physician prescribed one medication after another in an attempt to relieve the pain. Some experienced a certain pain-relieving effect from medication but many experienced strong side effects. Many described a lack of continuity in treatment, physicians being changed, and receiving treatment at different places for different, related symptoms. Several participants had a physician who treated menstrual pain (with medication) in one place, another physician in the vulva team at the hospital who treated the vulvodynia (with medication), and a physician at a primary care centre who prescribed sick leave. Often this physician also prescribed medication, such as sleeping pills or/and antidepressants for exhaustion and depression, which was largely caused by the prolonged pain problem.

Favourable treatment that makes a difference

There was overwhelming consensus among the participants on what was considered helpful. Knowledge of their own body and training in pain management made a difference. A clear rehabilitation plan helped reduce anxiety and stress.

Increased knowledge of the body and pain

All participants described the importance of understanding their bodies and understanding how the muscles work and how the body reacts to pain. Some experienced pain relief from relaxation exercises given by the midwife in the team, but it was only when the women understood the purpose of the exercises and how they could affect the pain that they became effective. Acupuncture was sometimes offered as pain relief; the same applied here; it gave temporary relief, but for a deeper effect, the participants needed training in pain management and knowledge of their bodies. All participants also stressed that it was necessary to get to know their body to know when it was tense and when it was relaxed. One participant mentioned that it was easier to get to know the muscles through manual guidance in the form of vaginal palpation by the physiotherapist than only through verbal instruction.

I feel like the physiotherapist has been very important to me. It was only when I came to her that I felt like, now I’m really getting help. Because you can be sent home with xylocaine and medications - but it was only when I came to the physiotherapist that I got this better understanding of how everything is connected. #4

Guided pain and touch therapy

The importance of regular manual guidance was strongly emphasised, largely because the participants were unable to provoke the pain on their own and thus break the ingrained avoidance behaviour.

She [the physiotherapist] started by putting her hand on my thigh, then in the groin, then a finger on the outside of the vulva. Now she can put a finger in, and it feels okay. In the beginning, it felt very scary because it is so intimate, but I feel that this is what is needed. You can’t do it yourself. #5

Breathing exercises were reported to be central to the treatment regimen. They reduced pain and muscle tension in the body and were used frequently by all participants. Two participants had tried Botox injections for the pelvic floor, and both had experienced some effect, but they felt that it was not worth the money (part of the cost had to be paid by the patient) and that basic exercises, such as relaxation and touch/stretching were more important. Acceptance of their condition was mentioned by some as necessary to be able to take part in the treatment.

Strategies for stress management

The ability to manage stress and set boundaries was considered important and many said they wished they had received more help with this from the vulva team. Another important aspect was that the care professionals should not be stressed but should be calm and pedagogical. Also, there must be room to ask questions and get explanations.

The physiotherapist confirms without downplay it and then you understand that, okay, I think this is difficult and it’s related to avoidance. She has been of great help in explaining and understanding that – okay, it is a symptom of this behavior. #7

In addition to specific relaxation exercises for the pelvic floor, several participants had started using other general relaxation techniques, such as yoga, mindfulness, and acupressure mat, often after advice from the physiotherapist. Participation in such training was experienced as very helpful.

The path forward—requests from the women

This category describes the women’s experiences in the health care chain, with requests for improvement, as well as their own goals for achieving improved quality of life.

Goals for better quality of life

The goals that were set depended on the women’s degree of discomfort. The goal set by those who only had pain during intercourse was to be able to have pain-free intercourse or at least sexual functioning from time to time. For couples, the goal was to explore each other’s sexuality or to be able to have children naturally. Those who had pain even in everyday activities wanted to be able to wear whatever clothes they wanted and to be able to ride a bike, sit without discomfort, etc. It was very inconvenient to always have to think about which activities to avoid to avoid pain. As one participant said, ‘I wish that my vagina should not control my everyday life.’ #1.

For one participant, the goal was to be able to undergo a gynecological examination and take a Pap smear test. Another woman set herself the goal of daring to talk about her discomfort and touch her own body. For some, the first and foremost goal was to feel better and to be able to work. Many also had a subgoal, which was to do the exercises they had been given by the vulva team every day or a certain number of times a week and to learn to manage the pain.

Of course, I want to be completely healthy – I want to, really feel that this pain disappears. That would be so good. I think I have come a long way since the pain was at its worst. Because then I could hardly sit. So it has gotten better and we have still been able to have sex, even if it takes a very long time. But my goal is to try to do them [the exercises] a little every day. #6

Faster specialised help and a holistic approach

A regret expressed by all participants was that they had not received specialised rehabilitation earlier. They felt they could have been spared much suffering over many years had they received information and knowledge about PVD from the start instead of being prescribed medication, often with strong side effects.

Information and knowledge and knowing that there is a very good chance of getting better. A good prognosis. Because it is so easy to think, well now it’s like this and, well, it’s too bad. I end up like that a lot. Catastrophic thoughts. It’s hard to see because the exercises can feel so simple. And it can feel like, how can it help that I lie here and breathe and that I use this little vibrator a little. #10

Painful medical treatment for urethritis was mentioned as a contributing factor to the worsening of symptoms, as were other painful tests, such as a biopsy of vaginal tissue.

All participants stressed the importance of feeling supported and feeling that someone is taking responsibility and is guiding the rehabilitation process forward. Most felt that their responsibility was too great and that they could not manage the rehabilitation on their own. All participants emphasised the importance of competence among healthcare professionals in outpatient care. They wished that more physicians would, during the examination, consider the possibility that their patient might have PVD and would not merely focus on taking samples. Several women suggested that a more holistic approach in medicine was needed.

Suggestions for improvement

Several women suggested that there should be more information at youth and women’s clinics about PVD so that the condition would be recognised and more easily diagnosed. Some suggested that students should learn about PVD and related conditions in school. It was suggested that there should be a Swedish PVD website with information about where to turn for help depending on the region of residence and which interventions are offered. Several participants thought it would be good to have special women’s health centres combining all health care competences and all parts of rehabilitation. Here team treatment and group activities, such as yoga and meditation could be offered to groups of women with the same diagnosis. This would contribute to feeling less alone because others have the same diagnosis. Several participants expressed that yoga, meditation, or mindfulness should be included in the treatment regimen and should not have to be paid for out of pocket. One participant felt that healthcare was too routine and not open to alternative treatments. Those who had been on sick leave for a while all had in common a combination of long-term pain and a high degree of inner stress due to classic factors, such as high demands on self and difficulties in saying no. These participants expressed a desire for training in stress management and recuperation.

I think relaxation is very important for the body. I didn’t get much effect from Botox and I’ve noticed that a lot is mental. Not that the pain is not physical, because it is, but I think a lot sits in tension throughout the body. I think everything is connected and that non-traditional care can help a lot. It’s a high cost that one has to bear oneself, and I don’t think one should have to pay for it. #3

Some of those who received help from the vulva team explained that they did not feel they were in a group. They mentioned that it was unclear who was included and whom they would meet in the group. One participant said she had wanted to meet all team members at the first opportunity and receive information about the treatment offered by each one. Afterwards, the participants wanted to be able to use different competencies depending on their own needs. One of the participants suggested that it would be good to be able to request a male or a female gynaecologist; she saw this as a simple issue but said it would make a big difference to many women.

Discussion

The participants in this study found physiotherapy more helpful than a lubrication regimen and medication, which is in accordance with several other studies [Citation9,Citation11,Citation15,Citation23]. Its effect is to alleviate pain, reduce anxiety and catastrophizing, increase self-confidence, and improve quality of life. This study also describes the importance of the caregiver having the ability to communicate knowledge to the patient and explain the purpose of the treatment, for the treatment to be successful. Physiotherapists are suited for this role, but it still requires experience and high competence of the individual physiotherapist as well as the ability to create an alliance with the patient.

According to Berghmans [Citation24], physiotherapy is an underutilised resource for this patient group and should be included in all vulva teams. Receiving help to confront the pain was considered very important by the participants and something many could not do on their own because of fear of pain and long-term avoidance behaviour. Through manual touch therapy, a physiotherapist guided the women through the task of accepting, approaching, and daring to allow touch of the genital area. They would then practice touching their genital area on their own or with their partner. Like the participants in this study, the women in the study by Danielsen et al. [Citation1] described how they initially experienced such exercises as strange, uncomfortable, and scary. But later they realised that it was necessary to challenge their fear and the pain they had avoided for so long and when they did, they discovered that it was not as scary as they had thought. This balance is also discussed by Engman [Citation25] in her dissertation Vulvodynia: understanding the role of pain-related behaviour. Engman identified two models of behaviour. One is avoidance behaviour and the other is endurance behaviour. Both behaviours lead to long-term pain, and it is up to the therapist to find a suitable strategy regarding the balance between challenging and avoiding the pain [Citation25].

Many participants in this study said they wished they had met the physiotherapist in the first stage of the condition. In Sweden, a physician usually needs to exclude other medical causes of PVD, before the patient is recommended physiotherapy. This patient flow across the health care system creates long queues at vulva clinics and a delayed rehabilitation process. Physicians in primary care can refer patients directly to a specialised physiotherapist for quicker treatment if suspected of the diagnosis, but for this to happen, knowledge among the physicians at primary care centres is required, as is the presence of specialised physiotherapists. Referring to a physiotherapist without specialised knowledge in the subject would not be meaningful as the women, in this study, require healthcare professionals who know their conditions and have competence to deliver the treatment needs. It would be useful for the patient to start with specialised physiotherapy to gain knowledge about the body and pain management strategies before or at the same time as starting the process of excluding other medical causes. It would likely improve the women’s experience of care and prevent the condition from worsening.

Several participants asked for support in the form of a patient group where they could meet other women in the same situation. The value of sharing experiences has also been described in the study by LePage and Selk [Citation15]. Offering information and education about the body and providing pain training in a group instead of individually could potentially streamline the work of the vulva team and reduce waiting times. This would also satisfy the need to meet other women in the same situation. However, the results of this study also show that group treatment needs to be combined with individual treatment where the woman receives help to apply the general knowledge about pain to her own situation. Individual sessions are also needed to set individually designed goals and develop strategies to achieve these.

The study by LePage and Selk [Citation15] emphasised the importance of physicians excluding other medical conditions. At the same time, negative test results contributed to patients feeling disregarded and they risked being misdiagnosed with a psychiatric condition. This was reflected in the interviews in this patient population and is a clear reason why the participants wanted physicians, gynaecologists, and midwives to keep the diagnosis of PVD in mind when tests were negative, and to refer women with these symptoms to a specialised physiotherapist or a vulva clinic.

As in several other studies, the participants in this study expressed a desire for treatment from a multidisciplinary team [Citation8,Citation10,Citation15,Citation24]. The need for a multi-disciplinary team is linked to the complexity of the condition of PVD, as affected women need help from a sexologist, psychologist, physiotherapist, midwife, and physician. In this study, all participants were recruited from two different vulva teams that included several professions, but where the physiotherapist acted as both psychologist and sexologist because neither of these professions was represented. However, the participants did not see this as a major problem as long as they received help from the physiotherapist to handle issues related to sexuality and behaviour.

The study by Nygaard et al. [Citation9] compared team treatment with individual, specialised physiotherapy in primary care. Team treatment in their study consisted of pain education, body awareness, and cognitive techniques, and the specialised physiotherapist offered combination physiotherapy, including manual treatment (touch therapy and pain management), patient education, pelvic floor training, and home exercises. The results showed that patients who received team treatment experienced a greater reduction in pelvic floor pain, but no other parameters differed in terms of quality of life and function. The results of this study also suggest that it may not matter whether treatment is given in a team or individually as long as the patient’s needs for help are met [Citation9].

This suggests that the entire healthcare chain would gain valuable time and spare these women a lot of suffering if competence existed in primary care. A physiotherapist in primary care can more easily meet women’s needs for regular group treatment sessions in general relaxation training, in the form of basic body awareness, mindfulness, as well as pain management, and education in anatomy and physiology. The present study describes that treatment for this condition takes a long time at the beginning, but once the patient has received the tools to manage her situation, she can manage on her own with shorter follow-ups. The first couple of sessions, which involve education and the establishment of individual goals and strategies, together take 45–60 min. Specialised services in primary care that allow longer treatment times with higher compensation would be a solution that makes it worth it for physiotherapists in primary healthcare to further educate themselves on women’s health.

Strengths and limitations

Individual interviews allow for a deeper understanding of a subject than group interviews [Citation26]. Individual interviews are appropriate when seeking to delve into patients’ experiences and experiences of an intimate sensitive subject, such as PVD. The author (J.H.) used Teams to conduct the interviews. Face-to-face sessions were not possible due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic when physical contact needed to be limited. The advantages of conducting interviews via Teams are numerous [Citation27]. Teams allowed the interviews to be held despite a 200–600 km distance between participants and the researcher. This was advantageous both from an environmental and a time perspective. Another major advantage was that the participants could be interviewed in a private and secure environment (their own homes) which was especially important given the sensitive subject of this study. As the author (J.H.) has background knowledge in the subject, this may have contributed to good contact during the interview and, therefore, to the detailed answers received from the participants. However, it can also be a risk with digital interviews compared to face-to-face interviews. A risk with digital interviews is that the sound quality of the recording may be poorer and that the internet connection will not work optimally. These factors are much less evident in face-to-face interviews [Citation18]. Another risk is difficulty in confidence in the interview situation. However, studies have shown that digital interviews via Teams, or similar communication tools, provide an equivalent researcher—participant connection/contact to face-to-face interviews [Citation27].

The optimal size of the sample in interview studies is debated. According to Vasileiou [Citation28], an author needs to evaluate and report the adequacy of his or her sample. Researchers are recommended to look at previous studies to calculate how much data is needed to achieve a credible result. Furthermore, it is argued that data adequacy is best assessed by referring to the parameters measured in the specific study. Sandelowski [Citation29] recommends that the size of the sample in qualitative research should be large enough to discover a new and rich understanding of the phenomenon under study, but small enough for the deep case-oriented analysis of qualitative data not to be excluded. Previous studies have presented interesting and informative results from interviews with fewer than ten participants [Citation15,Citation16,Citation30]. Therefore, ten participants were deemed enough to achieve the purpose of this study [Citation31].

The credibility of a study is reinforced when the data analysis is openly described so that the reader can form his or her own picture of the results. The analysis process is described in detail throughout this study so that the reader can assess the consistency between the data presented and the study results [Citation32]. Furthermore, the credibility is strengthened when the spread of the collected analysis material is sufficient to give a robust picture of the phenomenon [Citation20]. It is argued that there should be sufficient data to cover significant variations. With this in mind, participants have been included from two different vulva groups in Sweden to get a wide range of experiences of care.

The analysis was performed in specific steps and with discussions, cooperation, and consensus between the authors. The first author has treated women with vulvodynia, which can be an advantage in the interviews but also influence the analysis. The authors have strived to be objective.

Transferability is another aspect of credibility. It is important to give a clear description of the selection criteria of the study, and of participants’ personal characteristics, as well as of the data collection and analysis [Citation19]. To strengthen transferability, the authors (J.H. and R.S.) have described the method in great detail and have strived for openness in the entire analysis work.

Conclusion

This study describes detailed feedback from the participants regarding which type of treatment makes the most difference for their condition and also their suggestions for improvements in health care. For the women, the most important aspect of the treatment was understanding their own bodies, understanding the purpose of the treatment, and getting manual guidance to break their fear of pain. A healthcare professional who can educate the patient and clearly explain the purpose of treatment should therefore be involved in the first stage. This finding is likely important to primary care providers as it may contribute to faster diagnosis and management. The information may also guide future political decisions and impact the patient flow for this patient category.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (482.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the participants in this study. Special thanks also to Åsa Rikner and Elin Werius, for excellent support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Danielsen KG, Dahl-Michelsen T, Håkonsen E, et al. Recovering from provoked vestibulodynia: experiences from encounters with somatocognitive therapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(3):1–10. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1442540.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein AT, Stockdale CK, et al. 2015 ISSVD, ISSWSH and IPPS consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain and vulvodynia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(4):745–751. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001359.

- Friedrich EGJr. Vulvar vestibulitis syndrome. J Reprod Med. 1987;32(2):110–114.

- Goldstein AT, Pukall CF, Brown C, et al. Vulvodynia: assessment and treatment. J Sex Med. 2016;13(4):572–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.020.

- Rosen NO, Dawson SJ, Brooks M, et al. Treatment of vulvodynia: pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Drugs. 2019;79(5):483–493. doi: 10.1007/s40265-019-01085-1.

- Uloko M, Rubin R. Managing female sexual pain. Urol Clin North Am. 2021;48(4):487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2021.06.007.

- Vasileva P, Strashilov SA, Yordanov AD. Etiology, diagnosis, and clinical management of vulvodynia. Prz Menopauzalny. 2020;19(1):44–48. doi: 10.5114/pm.2020.95337.

- Klotz SG, Schön M, Ketels G, et al. Physiotherapy management of patients with chronic pelvic pain (CPP): a systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2019;35(6):516–532. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2018.1455251.

- Nygaard AS, Rydningen MB, Stedenfeldt M, et al. Group-based multimodal physical therapy in women with chronic pelvic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2020;99(10):1320–1329. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13896.

- Ghai V, Subramanian V, Jan H, et al. A meta-synthesis of qualitative literature on female chronic pelvic pain for the development of a core outcome set: a systematic review. Int Urogynecol J. 2021;32(5):1187–1194. doi: 10.1007/s00192-021-04713-1.

- Katz L, Fransson A, Patterson L. The development and efficacy of an interdisciplinary chronic pelvic pain program. Can Urol Assoc J. 2020;15(6):E323–E328. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.6842.

- Ekdahl J, Flink I, Engman L, et al. Vulvovaginal pain from a fear-avoidance perspective: a prospective study among female university students in Sweden. Int J Sexual Health. 2018;30(1):49–59. doi: 10.1080/19317611.2017.1404543.

- Bergeron S, Reed BD, Wesselmann U, et al. Vulvodynia. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):36–10. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-0164-2.

- Morin M, Dumoulin C, Bergeron S, et al. Multimodal physical therapy versus topical lidocaine for provoked vestibulodynia: a multicenter, randomized trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;224:189.e1–189.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.08.038.

- LePage K, Selk A. What do patients want? A needs assessment of vulvodynia patients attending a vulvar diseases clinic. Sex Med. 2016;4(4):e242–e248. doi: 10.1016/j.esxm.2016.06.003.

- Ayling K, Ussher JM. “If sex hurts, am I still a woman?” The subjective experience of vulvodynia in hetero-sexual women. Arch Sex Behav. 2008;37(2):294–304. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9204-1.

- Johansson E, Danielsson L. Women’s experiences of physical therapy treatment for vulvodynia. Physiother Theory Pract. 2023;11:1–11. doi: 10.1080/09593985.2023.2233600.

- Bryman A. Social research methods. 5th ed. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2016.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures, and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren BM, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Lindgren BM, Lundman B, Graneheim UH. Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;108:103632. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632.

- Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031.

- Locke L, Neumann P, Thompson J, et al. Management of pelvic floor muscle pain with pelvic floor physiotherapy incorporating neuroscience-based pain education: a prospective case-series report. Aust N Zeal Cont J. 2019;25(2):30–38.

- Berghmans B. Physiotherapy for pelvic pain and female sexual dysfunction: an untapped resource. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29(5):631–638. doi: 10.1007/s00192-017-3536-8.

- Engman L. Vulvodynia: understanding the role of pain-related behavior. Örebro University. DiVA, id: diva2:1596703; 2021. Available from: www.oru.se/publikationer

- Dicicco-Bloom B, Crabtree BF. The qualitative research interview. Med Educ. 2006;40(4):314–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02418.x.

- Oates J. Use of skype in interviews: the impact of the medium in a study of mental health nurses. Nurse Res. 2015;22(4):13–17. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.4.13.e1318.

- Vasileiou K, Barnett J, Thorpe S, et al. Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7.

- Sandelowski M. Sample size in qualitative research. Res Nurs Health. 1995;18(2):179–183. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770180211.

- Hintz EA. The vulvar vernacular: dilemmas experienced and strategies recommended by women with chronic genital pain. Health Commun. 2019;34(14):1721–1730. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1517709.

- Kvale S, Brinkmann S. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [Qualitative research interviewing]. 3rd ed. Lund, Sweden: Studentlitteratur AB; 2014.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.