Abstract

Purpose

To address the high rates of sickness absence due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders in Western countries, this study assessed the measurement properties of six standardised physical assessments to aid in treatment planning and provide guidance in work participation decisions.

Materials and methods

Two expert panels of physiotherapists evaluated the assessments for content validity, while three physiotherapists evaluated inter-tester reliability. The assessments’ normative data from healthy participants were collected and compared to data from individuals on full sick leave due to MSK disorders. The participants on full sick leave included employees from healthcare, primary schools, and kindergartens.

Results

The expert panels considered the assessments as easy to administer, score, and relevant for their patients, aside from the ACR tender points test. Inter-tester reliability was high, with ICC2.1 values between 0.80 and 0.94, although two assessments showed high measurement error. Healthy participants performed significantly better on all assessments compared to those on full sick leave.

Conclusion

The assessments were generally considered relevant and beneficial in clinical practice when used for patients with MSK disorders. Five of the six assessments are valid and reliable for evaluating physical function in these patients and showed an excellent ability to discriminate between healthy individuals and those with MSK disorders on sick leave. These assessments have the potential to be useful in clinical practice, complementing a holistic evaluation of function and the ability to work. More research is needed to further explore their potential for assessing work participation and their applicability to different occupational groups.

Introduction

Work is considered a cornerstone of welfare in society and for individuals [Citation1,Citation2]. High rates of sickness absence due to musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders in Norway and other Western countries have driven a shift from diagnosing and pain relief towards improving function and work participation [Citation3,Citation4]. Functional assessments are valuable for informing treatment plans and assist in work participation decisions in patients with MSK disorders. The use of both standardised questionnaires and physical tests is advised, as they assess different but related aspects of function [Citation5–7]. The significance of physical function is highlighted within the International Classification of Function (ICF) framework [Citation8]. However, in the last decade, functional assessments have often been overlooked as outcome measures in studies involving patients with MSK disorders [Citation5].

Standardised physical assessments involve individuals performing tasks which typically mimic everyday activities and/or work-related tasks. Functional capacity evaluations (FCEs) are the primary tools used to assess an individual’s capacity to perform specific job-related tasks. They are commonly used in specialist clinics, workers’ compensation organisations, and insurance companies [Citation9,Citation10] and are often time-consuming, and require expensive equipment. However, there is a lack of validated physical assessments for patients with MSK disorders in primary healthcare.

In the Function, Activity, and Work (FAktA) project, a set of six standardised physical assessments were utilised to assist in treatment planning and work participation decisions. The assessments included the Back Performance Scale (BPS), Global Body Examination (GBE)- Flexibility, back endurance test, abdominal endurance test, high lift test, and test of ACR tender points [Citation11]. The assessments were chosen because they measure muscular strength/endurance, bodily flexibility and relaxation, and activities like lifting and picking up subjects from the floor and reflect the bodily function and activity dimensions of the ICF model [Citation8]. Moreover, a study by Strand et al. [Citation12] illuminated the participation aspect, as it demonstrated that scores on the BPS could differentiate between individuals with MSK pain who resumed work from those who did not. Similarly, Kvåle et al. [Citation13] reported enhanced movement, including scores on GBE-Flexibility, in patients who returned to work compared to those on sick leave.

Results from a cross-sectional study within the FAktA-project indicated that individuals on full sick leave exhibited significantly lower physical function, reflected by five of the six physical assessments, compared to those who continued working despite MSK disorders [Citation11]. A qualitative study found that both employees and managers appreciate the assessments’ ability to clarify physical function, leading to positive impacts on health and work participation [Citation14]. Validity and reliability have previously been examined for some of the assessments. However, the measurement properties have been examined in other contexts, with a different population and in some cases with smaller samples, and they have not been examined collectively as a set of assessments.

This study aimed to further evaluate the measurement properties of the proposed set of six physical assessments in individuals with MSK disorders, including content validity, inter-tester reliability, and discriminative validity between those on full sick leave and healthy participants. Additionally, the study sought to gather normative data from healthy participants for these assessments.

Materials and methods

Setting

This project is an offshoot of the FAktA-study, conducted at the University of Bergen from 2012 to 2017. The inter-tester reliability of the six physical assessments was assessed during the project period, while the content validity was explored in 2019. Normative data for the assessments were collected from 2016 to 2022, and discriminative ability was examined in 2023.

Subjects

The participants in the FAktA-project were employees from healthcare, primary schools, and kindergartens, all with MSK disorders. Two expert panels, comprising clinical practice and education physiotherapists, evaluated the content validity. For the normative data, healthy men and women, aged between 18 and 70, were recruited.

Study design and procedures

Evaluation of content validity

Two expert panel meetings took place from March to May 2019. Each panel consisted of six experienced physiotherapists from both clinical practice and physiotherapy education, with a range of 3 to 35 years of clinical experience, including two of the authors in each group. During these meetings, the panels discussed the usefulness of the six physical assessments regarding specific questions from the COSMIN checklist [Citation15]. These questions guided the evaluation of the assessments’ comprehensibility, relevance for the intended population, ease of scoring, overall appropriateness, and potential for clinical application. The participants received information about the assessments before the meetings, and the meetings commenced with a practical demonstration of the assessments. Most participants were familiar with some of the assessments, and a few had used all of them in their clinical practice. Each meeting lasted about one hour.

Inter-tester reliability

The reliability of six physical assessments was assessed from February to August 2014 on 48 healthcare workers with MSK disorders. They were examined with the set of assessments twice. Each examination lasted 15–20 min, with approximately a 30-minute break between them. Two different physiotherapists independently conducted the first and the second examination. To mitigate the impact of fatigue and pain on the test results, participants performed the assessments requiring the least effort first. Participants rated their pain using the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS) before each test; an increase of more than one level led to exclusion. Three experienced physiotherapists collaborated in practice sessions before commencing the study and jointly examined the first 10 participants. Each physiotherapist examined approximately 20 participants.

Normative data

A convenience sample of 152 healthy men and women, aged between 18-70, was recruited for testing from April 2016 to August 2022. The participants should be free from MSK disorders at the testing point. They were excluded if they had been on sick leave for MSK disorders in the past year or had experienced significant MSK pain in the preceding three months.

Discriminative ability

The results of the assessments conducted on 152 healthy participants in the normative data were compared to the results of 77 participants (from the FAktA-study) who were on full sick leave due to MSK disorders. Those who had been on sick leave for more than 4 months were excluded from the study.

The physical assessments

The selection of the six physical assessments was based on a comprehensive literature review and consultations with researchers and experienced clinicians. The assessments took 15–20 min to complete.

The Back Performance Scale (BPS) comprises five tests; the sock test, the pick-up test, the roll-up test, the fingertip-floor distance test, and the lifting test, and they capture flexibility in the back. Each test has a score from 0 to 3, giving a total score of 0–15, where higher scores indicate greater functional limitation. The BPS has demonstrated acceptable test-retest reliability in individuals with long-lasting low back pain [Citation16,Citation17]. Normative data (N = 150) showed an average score (mean) of 0.8 [Citation18].

Global Body Examination (GBE)-Flexibility includes six tests that evaluate trunk flexibility and relaxation during passive movements, each having a score from 0 to 7, and a sum score from 0 to 42, with 0 as the best score. Previous studies have shown good reliability between testers, and that GBE-Flexibility can distinguish between healthy individuals and different patient groups. Healthy individuals, (N = 34) had a sum GBE-Flexibility sum score of 7.2 [Citation19,Citation20].

The back endurance test (modified Biering–Sørensen test) evaluates the static endurance of the back extensors, measured in 0–240 s. It has demonstrated satisfactory test-retest reliability [Citation21,Citation22] and the ability to discriminate between individuals with and without low back pain [Citation23]. Healthy individuals (N = 475) scored a median of 97 s for men and 86 s for women [Citation21].

Endurance of abdominal muscles is evaluated using a three-level dynamic sit-up test with increasing demands at each level, with a score ranging from 0 (worst) to 15 (best) [Citation24]. To our knowledge, measurement properties have not been evaluated earlier.

A high lift test, modified from BPS, measures the number of craft lifts for 1 min, lifting a box (1.3 kilos) of weights of 2 kilos for women and 3 for men from waist to shoulder height. A reduced level of the high lift test has been related to full sick leave [Citation11].

Testing of 18 tender points by criteria from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR-18) was included to gain an overview of pain distribution [Citation25]. More tender points represent higher symptom pressure. The tender point scores have demonstrated good reliability [Citation26].

More information about the physical tests can be found in the previous article [Citation11].

Analyses

The qualitative data from the expert panel meetings were analysed by the authors (TA, LHM, TD) who were present in the panel discussion and took notes by hand. Together they discussed, summarised, and validated what was recorded.

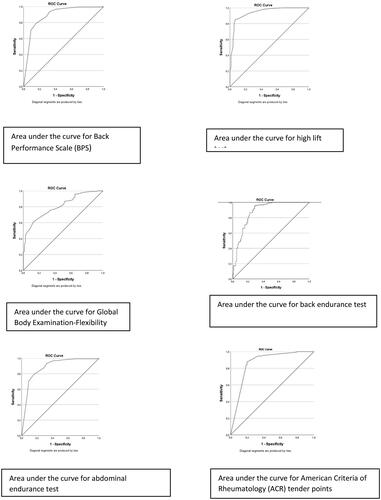

Descriptive analyses were used to describe demographic variables and normative data. Demographic variables included gender, age, education, smoking, exercise, pain intensity, and Body Mass Index (BMI). Data are presented as means with standard deviations (SD), or frequencies (n) and percentages (%), as appropriate. IBM SPSS Statistics, version 29; (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, 2022) was used for statistical analysis. Inter-tester reliability was examined with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC2.1) with a 95% confidence interval, within-subject standard deviation (Sw), and smallest detectable change (SDC). ICC from 0.7 to 0.89 is considered high intertester reliability and 0.90–1.0 is very high ([Citation27], p. 323). The student’s t-test was used to compare scores on the physical assessments between participants from the FAktA-project on full sick leave and healthy participants (normative data). Receiving Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) were used for contrasting scores of the two groups, with healthy participants as reference line 0. The greater the AUC, the better the variable discriminates. The AUC must be at least 0.70 to reach appropriate discriminative ability ([Citation28], p.208). Cut-off values, based on sensitivity and specificity estimations, were determined for all six assessments.

Results

Demographic variables for the participants in the inter-tester reliability study, the healthy participants, and those on full sick leave are listed in .

Table 1. Demographic variables.

Evaluation of content validity

The expert panels found the assessments easy to understand, learn and score, and relevant for their patients. The ACR tender points test was challenging to standardise and deemed less relevant due to its emphasis on pain rather than function. Moreover, proficiency in administering the GBE-Flexibility test, which evaluates relaxation and physical flexibility, necessitated some training. They suggested including assessments for neck and shoulder function but also stressed a limited set of assessments to get a general impression of the total function. Overall, they believed that the assessment battery was structured and simple enough to be used in clinical practice for patients with MSK disorders, especially for those with subacute and long-lasting low back pain.

Inter-tester reliability

The inter-tester reliability was found to be high for all assessments with ICC2.1 values ranging from 0.80 to 0.94 (). The absolute reliability expressed as measurement error had a moderate degree of measurement error for four of the assessments and a high degree of measurement error for two assessments (abdominal endurance test and ACR-tender points).

Table 2. Intertester reliability and measurement error between three testers for six physical tests N = 48. Mean score for each test is listed for test time 1 and 2*.

Normative data

Characteristics are listed in and results in . There was an increased likelihood of higher (worse) scores for GBE-Flexibility and the BPS scores and lower (worse) scores for endurance of back muscles in the eldest groups and for men.

Table 3. Normative data from healthy participants, scores on the physical tests.

Discriminative ability

The included material consisted of healthy workers of comparable age as those on full sick leave in the FAktA-project, but they differed regarding education level, smoking and exercise habits. Healthy participants performed significantly better on all physical assessments compared to those on full sick leave (p < .001) (). AUC ranged from 0.81 to 0.94, with scores above 0.90 for BPS (0.92, cut-off 3.5, sensitivity 0.93, specificity 0.74) and the high lift test (0.94, cut-off 15.5, sensitivity 0.90, specificity 0.83) ().

Table 4. Ability to discriminate between participants on full sick leave and healthy participants.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the measurement properties of a set of six physical assessments. The assessments were generally considered relevant and useful in clinical practice, except for the ACR tender points. All six assessments demonstrated good inter-tester reliability, but the abdominal endurance test and the ACR tender points had high measurement errors. Healthy participants outperformed those on full sick leave in all physical assessments.

According to the ICF model, physical, mental, and social aspects of functioning, as well as environmental work demands, and personal factors should be considered when assessing work participation [Citation8]. In our study, the main focus was on physical function, and we selected feasible assessment tools related to MSK health and disorders that easily could be used, without expensive equipment, by clinicians in primary care in planning of treatment and advising on work participation. Other assessments such as FCE tools, provide a more comprehensive measure of an individual’s ability to perform various work-related activities such as overhead working, bending forward, and carrying [Citation29,Citation30]. However, they are more costly and time-consuming and are not as suitable for use in primary health care.

To ensure the usefulness of the six physical assessments for patients with musculoskeletal (MSK) disorders, they need to demonstrate high-quality measurement properties. As part of the validation process, the content validity of the set of physical assessments was evaluated. According to the COSMIN checklist [Citation15] content validity concerns the relevance, comprehensiveness and comprehensibility of the assessments. We invited physiotherapists with experience in the assessment and treatment of patients with MSK disorders to evaluate the content validity.

They confirmed that the set of assessments displayed good content validity, except for the ACR tender points, which they found emphasised pain rather than function. Following the COSMIN guidelines [Citation15], the assessments were deemed easy to understand, relevant, and simple to learn and score. We propose excluding the ACR tender points from the set due to their pain-focused nature. The expert panels identified the set as most suitable for patients with subacute or long-lasting low back pain. However, a previous study conducted by Ask et al. [Citation14] found that other stakeholders, including employees with MSK disorders and their supervisors, found the assessments to be valuable in clarifying the level of function and promoting improved health and work participation, regardless of the specific ailments.

A crucial aspect of the quality of a test is its reliability and validity. We found high inter-tester reliability in all six assessments but with a high measurement error for the abdominal endurance test and the ACR tender points. As De Vet suggests ([Citation28], p. 120), reliability and validity should be tested in the target population. Prior validation studies have focused on long-term MSK disorders [Citation17,Citation20,Citation26] while our study also included short-term cases. Although past research used different populations and often small numbers, the ICC-values are comparable for the tests GBE-Flexibility, BPS, and ACR tender points [Citation17,Citation20,Citation31]. Alaranta et al. [Citation21] found somewhat lower values (worse) for the back endurance test, but the reproducibility was tested with a one-year interval.

In clinical practice, it is essential to have normative data that can be used to compare patients’ health and functional status with that of healthy individuals who are similar in terms of age and sex. Consequently, reference data were collected for all six physical assessments. The results from the collection of normative data align with previous reference materials for BPS [Citation18] and represent enhancements for the back endurance test [Citation21]. However, Alaranta et al. [Citation21] also included persons with low back pain during the last 12 months. Surprisingly, the back endurance test results showed a trend where women outperformed men. This could be explained by the use of a standardised bench, which may have favoured women because they are shorter and therefore have more bodily support from the bench compared to men. Our study revealed a higher (worse) sum score (11.8) for GBE-Flexibility compared to Kvåle et al.’ study [Citation19], which reported a sum score of 7.2, albeit with a smaller sample size of 34 participants.

In our study, all six physical assessments were excellent at distinguishing between healthy individuals and those on full-time sick leave, underscoring their relevance in evaluating work participation. Our findings are consistent with the systematic review by Hurri et al. [Citation5], who identified the BPS and a back endurance test as promising indicators for predicting return-to-work (RTW) for patients with low back pain. Further, Kvåle et al. [Citation13] reported improvement in movements, including the GBE-Flexibility score, in patients who returned to work compared to those who remained on sick leave following rehabilitation. Moreover, these findings align with the study by Soer et al. [Citation30], which revealed lower functional capacity, measured by the FCE-tool, in employees with MSK disorders on sick leave compared to a healthy group.

In addition to physical assessments, it is important to consider other factors when evaluating work participation. Combining validated questionnaires about psychosocial factors and work demands with physical assessments may hold promise [Citation5–7,Citation32,Citation33]. Further research is needed to explore the potential advantages of this integration.

Limitations

The present study is subject to several limitations. The FAktA-project primarily included workers in healthcare, primary schools, and kindergartens, potentially limiting generalisability to other occupational groups, such as office workers or occupations predominately comprised of male workers. Still, the results align with previous studies conducted by Soer et al. [Citation30] and the systematic review by Hurri et al. [Citation5], both of which included a higher proportion of men and participants engaged in sedentary work. These consistent findings across different studies add significance to the results.

It is important to consider the potential selection bias in the healthy reference group. This group exhibited higher levels of education, engaged in more physical exercise, and had lower rates of smoking compared to individuals on sick leave. Unfortunately, we were unable to recruit participants with more diverse educational levels and a higher number of non-exercisers in the healthy group. These factors, and particularly the exercise level, may have influenced the observed differences in the physical assessments between the two groups. However, it is noteworthy that the normative data obtained for the BPS were in line with findings from previous research. The expert panels of physiotherapists primarily emphasised the evaluation of physical function and daily living activities when evaluating the effectiveness of the set of assessments. Incorporating feedback from physiotherapists on using these assessments for advising on work participation could have provided valuable insights. Additionally, including other professions like physicians and occupational therapists may have offered broader perspectives on the applicability of the assessments.

Conclusion

The assessments were generally considered relevant and beneficial in clinical practice when used for patients with MSK disorders. Five of the six assessments are valid and reliable for evaluating physical function in these patients and showed an excellent ability to discriminate between healthy individuals and those with MSK disorders on sick leave. These assessment tests have the potential to be useful in clinical practice, complementing a holistic evaluation of function and the ability to work.

While some assessments were originally developed in Norway, they have been widely published and recognised internationally. More research is needed to further explore their potential for assessing work participation and their applicability to different occupational groups.

Ethics statement

The FAktA-project has been conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK 2011/2264). All participants received written and oral information about the project prior to the study, before signing informed consent. There are no conflicts of interest in the project.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants who used their time to join the project and the Norwegian Fund for Post-Graduate Training for Physiotherapy for funding the FAktA-project. We will also thank physiotherapist, MSc. Lise Krohn Knudsen for her contribution to this work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Helsedirektoratet. Tilstand og utfordringer på arbeid-helseområdet; 2019 [cited 2024 February 14]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/rapporter/tilstand-og-utfordringer-pa-arbeid-helseomradet/Tilstand%20og%20utfordringer%20på%20arbeid%20-%20helseområdet.pdf

- Waddell GBA. Is work good for your health and well-being? London: Stationery Office; 2006.

- Costa-Black KM, Loisel P, Anema JR, et al. Back pain and work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24(2):227–240. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.11.007.

- Helsedirektoratet & Velferdsdirektoratet. Strategi for fagfeltet Arbeid og Helse; 2021 [cited 2024 February 14]. https://www.helsedirektoratet.no/tema/arbeid-og-helse/Strategi%202021%20–%20Strategi%20for%20fagfeltet%20arbeid%20og%20helse.pdf

- Hurri H, Vänni T, Muttonen E, et al. Functional tests predicting return to work of workers with non-specific low back pain: are there any validated and usable functional tests for occupational health services in everyday practice? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(6):5188. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20065188.

- Wand BM, Chiffelle LA, O’Connell NE, et al. Self-reported assessment of disability and performance-based assessment of disability are influenced by different patient characteristics in acute low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2010;19(4):633–640. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-1180-9.

- Wind H, Gouttebarge V, Kuijer PP, et al. Assessment of functional capacity of the musculoskeletal system in the context of work, daily living, and sport: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(2):253–272. doi: 10.1007/s10926-005-1223-y.

- World Health Organization. The International classification of function, disability and health:ICF; Geneva,Switzerland: WHO; 2001.

- De Baets S, Calders P, Schalley N, et al. Updating the evidence on functional capacity evaluation methods: a systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(3):418–428. doi: 10.1007/s10926-017-9734-x.

- Strong S, Baptiste S, Clarke J, et al. Use of functional capacity evaluations in workplaces and the compensation system: a report on workers’ and report users’ perceptions. Work. 2004;23(1):67–77. https://content.iospress.com/articles/work/wor00370

- Ask T, Skouen JS, Assmus J, et al. Functional evaluation of health care workers with musculoskeletal disorders on full, partial or not on sick leave. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:eS93. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2015.03.225.

- Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Ljunggren AE. Back performance scale for the assessment of mobility-related activities in people with back pain. Phys Ther. 2002;82(12):1213–1223. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.12.1213.

- Kvåle A, Skouen JS, Ljunggren AE. Sensitivity to change and responsiveness of the global physiotherapy examination (GPE-52) in patients with long-lasting musculoskeletal pain. Phys Ther. 2005;85(8):712–726. doi: 10.1093/ptj/85.8.712.

- Ask T, Magnussen LH, Skouen JS, et al. Experiences with a brief functional evaluation for employees with musculoskeletal disorders as perceived by the employees and their supervisors. Eur J Physiother. 2015;17(4):166–175. doi: 10.3109/21679169.2015.1061594.

- Terwee C, Prinsen C, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: A Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(5):1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0.

- Engh L, Strand LI, Robinson H, et al. Back performance scale (BPS): Funksjonsvurdering av pasienter med ryggplager i primærhelsetjenesten. Fysioterapeuten. 2015;82:22–27. https://www.fysioterapeuten.no/fagfellevurdert-rygg/back-performance-scale-bps-funksjonsvurdering-av-pasienter-med-ryggplager-i-primaerhelsetjenesten/123308

- Magnussen L, Strand LI, Lygren H. Reliability and validity of the back performance scale: observing activity limitation in patients with back pain. Spine. 2004;29(8):903–907. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00017.

- Myklebust M, Magnussen L, Strand L. Back performance scale scores in people without back pain: normative data. Adv Physiother. 2007;9(1):2–9. doi: 10.1080/14038190601090794.

- Kvåle A, Bunkan BH, Opjordsmoen S, et al. Development of the movement domain in the global body examination. Physiother Theory Pract. 2012;28(1):41–49. doi: 10.3109/09593985.2011.561419.

- Kvåle A, Ljunggren AE, Johnsen TB. Examination of movement in patients with long-lasting musculoskeletal pain: reliability and validity. Physiother Res Int. 2003;8(1):36–52. doi: 10.1002/pri.270.

- Alaranta H, Hurri H, Heliövaara M, et al. Non-dynamometric trunk performance tests: reliability and normative data. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1994;26(4):211–215.

- Biering-Sørensen F. Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine. 1984;9(2):106–119. doi: 10.1097/00007632-198403000-00002.

- Latimer J, Maher CG, Refshauge K, et al. The reliability and validity of the Biering-Sorensen test in asymptomatic subjects and subjects reporting current or previous nonspecific low back pain. Spine. 1999;24(20):2085–2089; discussion 2090. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199910150-00004.

- Suni J, Husu P, Rinne M. Fitness for health: the ALPHA-FIT test battery for adults aged 18-69. Finland: European Union; 2009.

- Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Report of the multicenter criteria committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(2):160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203.

- Ahmed S, Aggarwal A, Lawrence A. Performance of the American College of Rheumatology 2016 criteria for fibromyalgia in a referral care setting. Rheumatol Int. 2019;39(8):1397–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00296-019-04323-7.

- Carter R, Lubinsky J. Rehabilitaion research. Priciples and applications. United States of America: Elsevier; 2016.

- De Vet HC, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Practical guides to biostatistics and epidemiology. Measurement in medicine. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2011.

- Lakke SE, Soer R, Geertzen JH, et al. Construct validity of functional capacity tests in healthy workers. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2013;14(1):180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-180.

- Soer R, De Vries HJ, Brouwer S, et al. Do workers with chronic nonspecific musculoskeletal pain, with and without sick leave, have lower functional capacity compared with healthy workers? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012;93(12):2216–2222. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.06.023.

- Weiner DK, Sakamoto S, Perera S, et al. Chronic low back pain in older adults: prevalence, reliability, and validity of physical examination findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):11–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00534.x.

- Cronin S, Curran J, Iantorno J, et al. Work capacity assessment and return to work: a scoping review. Work. 2013;44(1):37–55. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed14&NEWS=N&AN=366403998. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2012-01560.

- Steenstra IA, Munhall C, Irvin E, et al. Systematic Review of Prognostic Factors for Return to Work in Workers with Sub Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(3):369–381. doi: 10.1007/s10926-016-9666-x.