Physiotherapy research is a complicated process. In most research that focuses on treatment efficacy, a single intervention is tested on a discrete, highly controlled group of research participants. This is necessary for clarity, because it helps us understand whether each intervention is beneficial, harmful or neutral, when delivered in isolation and compared to sensible and realistic control/sham interventions.

However, this pared-down, simplified approach seems a far cry from the reality of clinical physiotherapy – for two reasons. First, the efficacy of an intervention for such a ‘clean’ group of participants may have limited relevance to real-life clinical practice, where people seeking care often have more complex features such as comorbidities, subclinical mental health concerns, and psychological characteristics that are known to be less common amongst people who volunteer as research participants [Citation1]. Second, clinical physiotherapists rarely offer a single intervention in isolation; we typically use multimodal strategies. We often combine therapeutic relationship and education with other interventions such as exercise, goal-setting, or manual therapies, because a clinical assessment that reveals multiple targets for intervention calls for multiple strategies to achieve the desired clinical benefit.

As we acknowledge the mismatch between the controlled context of randomised controlled trials and everyday clinical practice, we must also acknowledge that our multimodal treatment strategies are hard to refine. There is a need to optimise our clinical approach by offering the right intervention(s) to the right person at the right time – and, simultaneously, to avoid offering interventions that might be either superfluous or harmful. Identifying low-risk, high-return interventions is the first step. Identifying which of these interventions is right for which person is an equally important second step, and arguably more challenging. Essentially, clinical physiotherapists need to know which interventions will help whom.

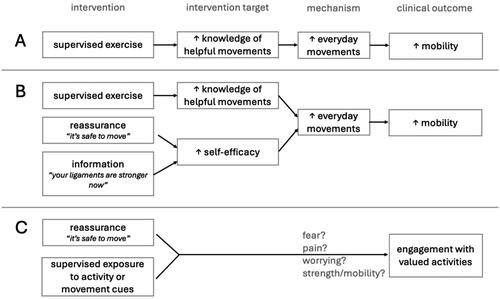

One way to assess the match between a certain intervention and a person seeking care is to consider whether the mechanisms that underlie the person’s health concern match the mechanisms that the intervention is thought to influence. provides a simplified example: when a person seeks care for stiffness twelve weeks after an ankle sprain, we might hypothesise that part of the mechanism underlying the lack of ankle mobility is a shortage of everyday movement (mechanism; we have observed that the person is avoiding plantarflexion). On speaking with the person, we learn that they are reticent to plantarflex because they are concerned that the ankle still needs to be protected after the sprain; they do not know which movements are safe and helpful. It is clear that the intervention needs to address this lack of knowledge (the intervention target). It is on these grounds that we choose an intervention: supervised ankle mobility exercises. uses the same framework with a multimodal approach that, although still simplified, gets closer to real clinical treatment: alongside the supervised exercise, we might also use reassurance and information to address the target of self-efficacy, which we also expect to increase the everyday movement that should improve mobility.

This simple example may seem too straightforward to warrant careful study. However, if we are to make progress towards more efficient, more effective treatments, we must achieve clarity about these intervention–target–mechanism–outcome paths. Our starting point will vary depending which relationships we already have data on. One topical example is the case of a person who seeks care for back pain because they are unable to engage in certain activities that are important to them (). Interventions consisting of reassurance alongside guided exposure/exercise are thought to improve function and promote re-engagement with valued life activities in people with pain [Citation2–4] (see a conflicting perspective at Devonshire et al. [Citation5]). However, there is uncertainty about the path between this intervention strategy and the clinical outcome [Citation6]. Can the benefit of this intervention be attributed to a change in fear? A change in pain? A change in worrying? Improved strength or mobility? Or all of them? And, equally important: could the path from intervention to clinical benefit differ for different people? Answering these questions would allow us to refine and optimise the intervention by refining its component parts. If the path does differ across people, more knowledge would allow us to offer the right version of the component to each person, depending on the mechanisms that are most prominent in them. With respect to this particular example, there has been some progress: some evidence supports that altering learned fear to reduce avoidance of feared activities is a path by which exposure interventions can improve function and support re-engagement. However, fear is not reported as a dominant feature by every patient who benefits from an exposure intervention. A second possible path is that an exposure intervention could alter learned pain to reduce avoidance of painful activities and improve function. The difference between these two paths may seem trivial, but it is not: the first is supported by a considerable body of evidence [Citation7]; the second, although popular amongst clinicians [Citation8] and theoretically plausible, has (at best) tenuous support from quality evidence [Citation9]. Clarity about these and other possible mechanistic pathways could provide a springboard for more effective, efficient interventions and better matching of intervention to care-seeker.

Physiotherapy is well positioned to follow the lead of our colleagues in mental health research, who have been using this intervention–target–mechanism–outcome framework for some time. Mental health also has a plethora of multimodal treatments, each showing their own combination of benefit for some people and no benefit for others. The need for greater clarity has been raised by many in that field [Citation10,Citation11]. The Wellcome Trust recently took on this challenge. Using the metaphor of searching for ‘active ingredients’ in adolescent mental health, this major funder commissioned a series of high-quality reviews to investigate the relationships between intervention, presumed mechanism and clinical outcome, across 46 different potentially active ingredients thought to address mechanisms spanning behaviours to socioeconomic influences [Citation12]. The initial findings of this structured review exercise are already showing signs of coherence: it seems that several diverse interventions (that have previously been assumed to address different mechanisms) actually all alter the same mechanisms to achieve their clinical benefits – a finding that lines up with other, similar analyses [Citation13].

What would it look like to take an ‘active ingredients’ approach to studying the interventions that physiotherapists commonly use? In research, we need to study each element and relationship in the interventional path shown in : the intervention, target, mechanism, the clinical outcome(s) of interest and the relationships between them. At the early stages of this approach, it may be most productive to study multiple potential mechanisms. We may need to use diverse approaches ranging from observational (including qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods) to experimental methods. We can expect complexity: certain targets may relate to more than one mechanism–outcome path, and we will need to study and understand this complexity. We will need to carefully distinguish between causative relationships and non-causative associations. Controlled experimental studies – particularly, those that directly manipulate the proposed mechanism – will be useful for this distinction. The concept of moderation will also be relevant [Citation11]. For example, baseline features of an individual seeking care (e.g. psychological flexibility) may moderate the relationships along the path from intervention to outcome. In the context of multimodal interventions, some components of an intervention may not directly relate to the intervention-to-outcome path, but may be supportive of other, active components – a valuable nuance that would provide the rationale to retain the supportive component as we refine the intervention.

Is this way of thinking about physiotherapy interventions relevant to current clinical practice? I believe it offers a useful framework for careful clinical reasoning, and could guide reassessment-based adjustments of individual treatment programmes. We typically monitor outcomes, and many of us monitor the implementation of our interventions (‘How many times this week did you do your exercises?’), with each person seeking care. We could also monitor mechanisms, to understand the levels at which changes are happening or seem to be blocked. For example, if we hypothesise a causal pathway from the belief that pain indicates catastrophic tissue damage, through fear of pain, to avoidance of activities, it would be sensible to (repeatedly) reassess beliefs about pain, fear of pain, and activity avoidance, as we implement an intervention to address the beliefs about pain. In this case, if there is no change in the outcome, we will have enough information to identify the point of breakdown in the hypothesised path from intervention to outcome, and to change the strategy and/or hypothesis. In this way, this framework has the potential to facilitate more systematic adjustment of individual treatment programmes based on response – or lack of response – in the target, mechanism or outcome. The framework also has the potential to improve communication between clinician and the person seeking care, and between clinical professionals. For example, the primary purpose of grading exercises after an ankle sprain can be either to protect a fragile ligament or to increase confidence. Twelve weeks after an ankle sprain, clearly framing the grading of exercises as a strategy to foster confidence, not to protect a ligament, would better position the person seeking care to implement the graded exercise strategy in a way that actually fosters their confidence and improves the outcome. Thus, openly discussing the hypothesised mechanisms along the intervention-to-outcome pathway stands improve transparency, agency, and – I postulate – may also enhance engagement and collaboration for the person seeking care and their clinical team.

This framework is not my own, and it is not new. However, I see its potential to support our transition into the next ‘era’ of physiotherapy research. We need clinicians and researchers to think and work together, using common frameworks. We need refined, efficient interventions. We need to understand the effects of our interventions – both intended and unintended effects. We need to understand who will benefit most from each intervention, and how to appropriately modify our interventions for optimal results for each person. Careful, structured testing of these intervention–target–mechanism–outcome paths has the potential to give us this information, and thus to equip us to do better for those who seek our care.

Disclosure statement

VJM has received payments for lectures on pain and rehabilitation, and is an associate director of the not-for-profit organisation, Train Pain Academy.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Karos K, Alleva JM, Peters ML. Pain, please: an investigation of sampling bias in pain research. J Pain. 2018;19(7):787–796. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.02.011.

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, et al. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4(4):CD011279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3.

- Kent P, Haines T, O’Sullivan P, et al. Cognitive functional therapy with or without movement sensor biofeedback versus usual care for chronic, disabling low back pain (RESTORE): a randomised, controlled, three-arm, parallel group, phase 3, clinical trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10391):1866–1877. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00441-5.

- Martinez-Calderon J, García-Muñoz C, Rufo-Barbero C, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain: an overview of systematic reviews with meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Pain. 2024;25(3):595–617. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2023.09.013.

- Devonshire JJ, Wewege MA, Hansford HJ, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive functional therapy for reducing pain and disability in chronic low back pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2023;53(5):244–285–285. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2023.11447.

- de Jong JR, Vlaeyen JW, Onghena P, et al. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain: education or exposure in vivo as mediator to fear reduction? Clin J Pain. 2005;21(1):9–17, discussion 69–72. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200501000-00002.

- Meulders A. Fear in the context of pain: lessons learned from 100 years of fear conditioning research. Behav Res Ther. 2020;131:103635. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103635.

- Madden VJ, Moseley GL. Do clinicians think that pain can be a classically conditioned response to a non-noxious stimulus? Man Ther. 2016;22:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.12.003.

- Madden VJ, Harvie DS, Parker R, et al. Can pain or hyperalgesia be a classically conditioned response in humans? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med. 2016;17(6):1094–1111. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv044.

- Holmes EA, Ghaderi A, Harmer CJ, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on psychological treatments research in tomorrow’s science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(3):237–286. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30513-8.

- Kazdin AE. Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3(1):1–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432.

- Wolpert M, Pote I, Sebastian CL. Identifying and integrating active ingredients for mental health. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(9):741–743. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00283-2.

- Schemer L, Schroeder A, Ørnbøl E, et al. Exposure and cognitive-behavioural therapy for chronic back pain: an RCT on treatment processes. Eur J Pain. 2019;23(3):526–538. doi: 10.1002/ejp.1326.