Abstract

Introduction

Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) often require treatment from different healthcare professionals at different levels of care. Previous research indicates shortcomings in interprofessional collaboration and rocky transitions between primary care, specialised care and long-term care.

Aim

The aim was to explore how nurses and physical therapists experience their role in interprofessional collaboration and the care delivery pathway for patients with COPD.

Methods

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with nurses (n = 4) and physical therapists (n = 7) from different levels of care between October 2020 and January 2021 and analysed using qualitative content analysis.

Results

Insufficient time and continuity along with unclear routines were perceived as inhibiting interprofessional collaboration and transitions within the care delivery pathway. Dialogue between healthcare professionals was considered important to increase familiarisation with other professional roles and to enhance mutual support. Insufficient competence and low priority in healthcare was perceived as placing responsibility on the silent patient group to contact healthcare for follow-ups.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the experiences of nurses and physical therapists regarding several insufficiencies in interprofessional collaboration and the care delivery pathway. It is necessary to increase COPD-related competence among healthcare professionals, develop and clarify routines and provide conditions for dialogue between healthcare professionals.

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a complex condition, characterised by chronic respiratory symptoms such as dyspnoea and cough [Citation1,Citation2]. In addition to respiratory symptoms, manifestations beyond the lungs are also present such as skeletal muscle dysfunction and reduced physical capacity and physical activity [Citation2–5]. Patients with COPD can also suffer from exacerbations, acute deterioration of respiratory symptoms, which result in further reductions in muscle strength and physical activity [Citation6]. Furthermore, comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases, osteoporosis, anxiety and depression are more common in patients with COPD than in the general population [Citation7,Citation8]. Altogether, these symptoms and comorbidities lead to a decrease in quality of life and increase the risk of morbidity and mortality [Citation2–5,Citation9]. Since the disease is heterogeneous, patients have different needs for healthcare support depending on the current state of their disease, which may fluctuate repeatedly over time [Citation2,Citation10]. Pulmonary rehabilitation – comprehensive, patient-tailored intervention including, but not limited to, exercise training, education and behaviour change – is a core component in the management of patients with COPD [Citation4]. To meet each patients’ unique needs, the intervention should be implemented by an interprofessional team [Citation4], meaning that several healthcare professionals of different occupations work together to achieve common treatment goals [Citation2,Citation11]. Multiple interventions involving interprofessional collaboration can improve disease-specific quality of life and exercise capacity and decrease the number of hospital admissions and hospital days for patients with COPD [Citation12].

Due to the complex nature of COPD, healthcare interventions at different levels of the care delivery pathway (such as specialised care, primary care and long-term care) are often needed [Citation11]. Inspired by Kayyali et al. [Citation13], we define ‘care delivery pathway’ as the coordination of healthcare services provided to patients with COPD in specialised care, primary care and long-term care. Over time, patients with COPD may move several times between different levels of care and healthcare providers, which demands smooth transitions and continuity of care [Citation10]. To achieve comprehensive COPD management, it is therefore important that healthcare services are well coordinated within the care delivery pathway as well as between healthcare professionals. The aim of the guidelines from the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare is to achieve a smooth transition within the care delivery pathway so patients do not perceive that there are different care providers [Citation11]. However, patients with COPD sometimes lack such a smooth transition, stopping the care process; e.g. when being discharged from the hospital [Citation14]. Therefore, communication between healthcare professionals at different levels of care is deemed important by patients with COPD, especially for patients with more severe disease who are in need of more comprehensive services in several levels of care [Citation14]. Continuity of care is especially important for patients with COPD, since being known to their healthcare provider can have a positive impact on their sense of security and experienced quality of care as well as contribute to reflection among healthcare professionals on the bigger picture [Citation10,Citation14,Citation15].

The perception of healthcare professionals regarding care delivery pathways for patients with COPD have been explored by Kayyali et al. [Citation13] in England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Greece and Germany. Several challenges were emphasised, such as a lack of communication, limited resources and difficulties with engaging the patients. Additionally, care delivery pathways differed somewhat between countries, where only England and Ireland provided home-based interventions. However, it is unclear which levels of care the healthcare professionals included in the study worked in [Citation13]. Previous Swedish studies also indicate shortcomings in care delivery pathway transition and interprofessional collaboration, but the aim of these studies have not been to study the care pathway or interprofessional collaboration specifically, and they have only explored each level of care independently [Citation16–18].

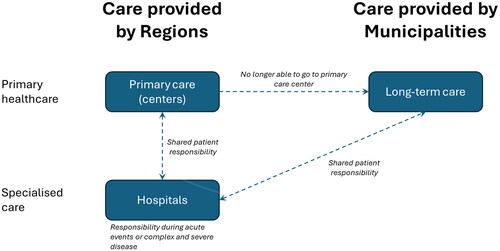

The healthcare system in Sweden differs from healthcare systems in many other countries. Most Swedish healthcare services are publicly funded, and the responsibility is divided between 21 regions and 290 municipalities. Below is a description of the context relevant for this study, as illustrated in . Licenced staff providing care in both regions and municipalities include nurses, physical therapists and occupational therapists. However, municipalities cannot employ physicians; therefore regions organises and provide physicians for municipalities [Citation19].

Primary healthcare is provided by both regions and municipalities, but the care pathway begins at regional primary care centres for most people, including patients with COPD. Municipalities take over the responsibility and provide long-term care for patients who are no longer able to travel to their primary care centre or are no longer able to live independently. Long-term care includes both home healthcare (i.e. care provided in the patient’s ordinary home) and nursing homes (i.e. care provided in the patient’s private room of a residence with attending staff) [Citation19].

Specialised care, in hospitals is provided by regions. Consequently, during acute events, such as exacerbations that requires hospital care, specialised care temporarily takes over responsibility for the patients’ healthcare [Citation19]. For some of patients with more severe COPD, specialised care takes over the main responsibility of their COPD care from primary care or long-term care.

Previous research has shown low access to healthcare interventions performed by interprofessional teams, such as pulmonary rehabilitation [Citation20]. Interprofessional collaboration can contribute to a higher quality of care including a decreased burden on the healthcare system [Citation21]. To facilitate a successful implementation of guidelines for interprofessional collaboration in COPD care, it is important to be armed with knowledge about the current prerequisites [Citation22]. However, due to a lack of existing evidence, it is important to further explore interprofessional collaboration in the care delivery pathway and to include multiple levels of care. Nurses and physical therapists are two professions with important roles in the management of COPD [Citation2,Citation4,Citation11]. In previous studies that investigated Swedish primary care and long-term care, nurses were described as having a central role and as coordinating COPD management [Citation16,Citation17]. The role of physical therapists, on the other hand, is to promote increased physical activity and exercise – something that is highly recommended in treatment guidelines [Citation2,Citation4,Citation11]. However, in clinical everyday life, this is not offered to patients with COPD enough [Citation20]. Therefore, the perspectives of nurses and physical therapists are specifically important to explore.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore how nurses and physical therapists experience their role in interprofessional collaboration and the care delivery pathway for patients with COPD.

Materials and methods

This is a qualitative inductive interview study with a phenomenological approach [Citation23,Citation24]. Qualitative content analysis [Citation25] was used as an analytic tool in order to gain an understanding of the participants’ experiences.

Settings

This study was conducted in several cities in a healthcare region in Northern Sweden. It included both specialised care in hospitals, primary care in regional primary care centres and long-term care in the municipalities.

Recruitment and participants

Convenience sampling was applied in the study [Citation25]. Inclusion criteria for participants were: (i) nurse or physical therapist from specialised care, primary care, or long-term care; (ii) someone who recurrently cares for patients with COPD; (iii) and who understands and speaks Swedish. To achieve a variety of experiences, we strived for a variation regarding gender, age and experience in the profession.

Information and invitations to the study were sent to 33 unit managers at workplaces in specialised care, primary care and long-term care in all municipalities in the healthcare region. This was intended to capture a spread of participants from rural areas, small towns and medium-sized cities, since variation in multiplicity is emphasised in qualitative content analysis [Citation24]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic made it difficult to recruit participants, contacts were made with unit managers at more hospital wards, primary care centres and municipalities than was first planned, and several reminders were sent to the managers who did not answer. Out of the 33 unit managers, 11 did not answer the invitation, 3 announced that they could not ask their staff due to the current situation regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and 19 answered that they had informed their staff about the study. In total, 19 suitable participants agreed to be contacted by the research group, either by e-mail or telephone. Fourteen persons requested additional written information. In the end, five persons had no interest participating in the study and three denied participation because of their high workload related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, 11 participants (8 women, 3 men) agreed to participate and were included. They worked at eight different units in specialised care, primary care and long-term care. Three units contributed two participants each who had different perspectives, either related to having different professions or previous experience from different levels of care. Overall, several participants had working experience from more than one level of care. Background data are provided in .

Table 1. Background information of study participants.

Data collection

The first author (ÅW) created a semi structured interview guide with open-ended questions [Citation26]. The questions focused on interprofessional collaboration within each participants’ own level of care and in the care delivery pathway between specialised care, primary care and long-term care for patients with COPD. A pilot test of the interview guide, meant to improve the quality of data collection [Citation26], was conducted with a physical therapist who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A few changes were made after the pilot interview; e.g. some questions were modified to be open-ended (Box 1).

Because of the prevailing pandemic, all interviews were conducted by the first author (ÅW) individually by telephone. She had no previous relationship with the participants, except one. The participants were informed that she was a registered physical therapist and master’s student. However, a few participants were aware that she also was hired as a physical therapist in long-term care. At the end of each interview, ÅW summarised what the participants had talked about to give them the opportunity to clarify or add more information. All interviews were audio recorded and lasted between 39 and 68 min and no field notes were made. The interviews were transcribed verbatim by the first author and a professional transcriber. Data collection was conducted between October 2020 and January 2021.

Data analysis

Inductive qualitative content analysis as described by Graneheim and Lundman [Citation25] was used, to identify patterns in the data material. Initially, the recorded interviews were listened to and read through to get a sense of the whole. Sentence units were identified that responded to the purpose of the study. These sentence units were condensed, abstracted and labelled with a code. The codes were compared for similarities and differences and were sorted into subcategories and categories. The coding process was done using Open Code 4.03 software [Citation27]. An example of the analysis process is shown in .

Table 2. Examples of the analysis.

The analysis was performed by ÅW in close collaboration with SL, both of whom were involved in all steps of the analysis. Researcher triangulation with all researchers in the research group was used regularly in the analysis process to discuss and revise the emerging analysis and to verify that it was based on collected data. Participants were not asked to comment on neither interview transcripts or on the findings. To enhance credibility, the COREQ checklist was used when reporting the study [Citation28].

Research team and reflexivity

ÅW, who conducted the interviews and performed the data analysis, is a registered physical therapist (RPT) with a MSc in physiotherapy. She has extensive experience in clinical work in long-term care.

GS, who was involved in interpretation of the data analysis, is a RPT with a PhD in physiotherapy. She has extensive experience in qualitative research within physical therapy and clinical work in primary care.

SL, who supervised ÅW during the interviews and was involved in the data analysis, is a RPT with a PhD in physiotherapy. She has experience in qualitative research pertaining to the management of COPD in primary care and long-term care.

Altogether, the researchers contributed to the interpretation of the analysis with somewhat different perspectives from their clinical and research experiences, which was important for dependability [Citation24,Citation25].

Results

The inductive qualitative content analysis resulted in three categories: ‘inadequate organisational support’, ‘desired collaboration to boost competence’ and ‘patients left to cope by themselves’. Each category consisted of three to four subcategories (). The categories and subcategories are presented together with selected quotes from participants.

Table 3. Categories and subcategories developed in the analysis.

Inadequate organisational support

This category reflects how participants experienced organisational barriers such as insufficient resources and routines. These barriers led to a lack of collaboration within and between levels of care and contributed to healthcare professionals working from different perspectives and missing a comprehensive picture of the patients.

Insufficient time and continuity

Participants experienced that interprofessional collaboration was negatively affected by insufficient time and access to other healthcare professionals. In addition, there was no time for team meetings and development work had to become less prioritised. Lack of continuity among staff was also highlighted as a barrier for interprofessional collaboration and participants experienced high staff turnover, especially among physicians and nurses.

I think that everyone wants to have that closeness and that good teamwork…but because there isn’t continuity in the roles and that the workload is high…it puts a spoke in the wheel…/…/…where there had been vacant roles or rotation of a lot of people. That causes the teamwork to fail… (Physical therapist, long-term care)

Unclear routines

Unclear or even non-existent routines were pointed out as a problem, both within and between levels of care. When the responsibilities between healthcare professionals within the organisation were unclear, it was seen as important and desirable to structure interventions based on current national guidelines. Furthermore, routines for contacts between healthcare professionals at different levels of care were experienced by participants as unclear and could end up in one-way communication, while others felt that routines existed and worked well. It was considered important to have several means of overreporting, such as written referrals, overreporting systems and phone calls, but at the same time this was expressed as difficult to keep track of.

It’s a lot of people to keep track of, but we usually try and collate telephone contact lists…and then you kind of have to cope as best you can…it’s like that in all of the cases, that it’s not always easy to make contact with the person you want…but, as I said, you usually get there in the end! (Physical therapist, specialized care)

Participants perceived a lack of clarity about which level of care (specialised care or primary care) was responsible for patients with more severe stages of the disease. In addition, if routines were unclear at one level of care, it also affected overreporting to and collaboration with other levels of care. Accordingly, the development of clear routines and structures for collaboration between levels of care was requested.

Disrupted process

Participants believed that good collaboration is cost effective and can increase knowledge of available interventions, but the collaboration between levels of care was considered inadequate. Because of rare reports from specialised care, it was difficult for participants in primary care and long-term care to support patients after inpatient care due to exacerbations.

A need for communication about responsibilities between healthcare professionals at all levels of care was considered crucial to ensure that the patient would reach the most appropriate level of care – e.g. it was expressed as important to have a more patient-centred approach when deciding on where physical exercise should be conducted.

If you are going to think energy-saving…it’s more than just a little effort for them many times to get themselves to the primary care center for their training…you maybe need to reason about it both internally and in some working group. That it’s going to be a sustainable effort that they will be able to do and not that they’ll be completely exhausted by…Then you’ve lost the effect of it a little bit… (Physical therapist, long-term care)

Participants emphasised the importance of a cohesive link throughout the whole care delivery pathway to make transitions between levels of care smooth for patients. This was considered especially crucial for older and frail patients with more complex needs. It was considered desirable to intervene with patients in earlier stages of the disease and work with a more preventive focus in collaboration between the levels of care.

Work from different angles

Insufficient interprofessional collaboration within the organisation resulted in a sense of professionals working from different angles. Even when participants expressed satisfaction with and routines for collaborations, these collaborations were mainly described as consulting colleagues or transferring cases to each other rather than working together as a team. A few examples of working in a team were reported, mainly in specialised care. Nurses, regardless of the level of care, were often described as a ‘spider in the web’ – coordinators who took on the responsibility of connecting other professions when needed.

Working in interprofessional teams was expressed as desirable for participants, to get a better overall picture of the patients, to share knowledge with each other and to discuss specific issues.

But I know that these patients are supposed to meet teams as well and then…yes, I wish that they would get…a well-oiled Asthma-COPD team. (Physical therapist, specialized care)

Including all professions in the team to provide interventions based on the patients’ many different needs was considered central. Primary care centres with perceived well-functioning asthma/COPD clinics and ‘driven’ physicians were considered to have better potential for good interprofessional collaboration.

Desired collaboration to boost competence

This category captures the need for dialogue and increased knowledge about the roles and interventions by different professions. Increased awareness facilitated collaboration and vice versa, which could lead to increased support between healthcare professionals.

Unclear physiotherapeutic role

Physical therapists expressed that their role in the COPD team was sometimes perceived as unclear among other professions and patients and was therefore important to clarify. The role was described as being under development and patients with COPD only met the physical therapist sporadically, based on the judgements of other professions.

Since many patients end up at the primary care center…it’s really important that they come to us [physical therapists]. Otherwise, we don’t have many opportunities to influence patients. (Physical therapist, primary care)

Patients mainly met with physical therapists at later stages of the disease for assessment and interventions for decreased physical functions rather than because of the COPD diagnosis. Consequently, this affected physical therapists’ ability to provide preventive interventions, which was expressed as a serious problem.

It was seen as positive to have certain physical therapists with responsibility for COPD management. Physical therapists also expressed that they then could share the coordinating role with the nurses. When the role of the physical therapist was clear, often in specialised care, interprofessional collaboration and collaboration between physical therapists at different levels of care were believed to be facilitated, and participants experienced obvious health benefits for the patients.

Important professional dialogue and familiarity

Regular network meetings within the professions, both within and between levels of care, were advocated as important. This gave healthcare professionals the opportunity to share knowledge and to discuss routines and working procedures related to specific diseases and care management.

We usually have some form of network meeting with specialised care and long-term care at regular intervals, so that could maybe be a point on the agenda. How are the transitions between us, the different levels of care? And which people do we have at each respective place who work actively with this category of patient so that you know which contact routes [exist] and you know what is offered at each level of care? (Physical therapist, primary care)

Participants described how dialogue and development work between levels of care had strengthened them in their work. This also clarified COPD management in the care delivery pathway, which improved patients’ transition between levels of care. Experiences working in several levels of care and working in smaller communities were also expressed as beneficial to enhancing collaboration and increasing familiarity with other professionals.

Interprofessional support

Increased interprofessional collaboration between as well as within levels of care was highlighted as important and desirable to strengthening each other and thereby increasing the quality of care. This could consist of knowledge support between professions within and between levels of care – something that was considered valuable in the mutual strengthening of roles within COPD management. For instance, participants described how they could consult colleagues at other levels of care about difficult issues related to COPD or support each other’s interventions.

COPD patient educations were emphasised as highly valuable for interprofessional collaboration. Having several professions involved in the programs facilitated the coordination of interventions and healthcare professionals could utilise each other’s competencies.

I think a type of COPD patient education more regularly would be really good to make use of each other’s competencies. I mean it can be occupational therapists, it can be dieticians…not to forget. And you could benefit from that… (Nurse, primary care)

Several conditions that could ensure good collaborations were mentioned, such as available systems for overreporting, an open communication climate at the workplace and the ambition and will to collaborate.

Patients left to cope by themselves

This category portrayed participants’ notion that this patient group is often forgotten and disregarded by the healthcare system and that responsibility for COPD management is often put on the patients themselves.

Insufficient COPD competence

According to the participants, a lack of competence regarding COPD and related interventions led to insufficient care for patients.

…many referrals are very broad in their question. And then you can interpret… maybe the competence within this area…there is a certain amount of room for improvement, if I read how the referrals are formulated. (Nurse, primary care and long-term care)

Varying COPD-related competence among physicians resulted in greater responsibility for nurses. In addition, insufficient knowledge about the roles of other professions made it impossible to identify the need for interventions. However, it was believed that increased knowledge could be facilitated by team meetings and discussions about routines for COPD management.

Low priority

Participants experienced that diagnoses like diabetes received more attention and had a higher status in healthcare than COPD. Patients with COPD were considered a ‘forgotten group’ who often were overlooked in the healthcare system. Shifting interest in structuring the work around the patient group, both within and between levels of care, was experienced as inhibiting patients’ transition between levels of care. In addition, nonchalant attitudes by healthcare professionals were reported.

I experience that, above all, COPD patients are met quite nonchalantly. This is because COPD has most often been caused itself through smoking and then it’s just like the patient has only themselves to blame… (Nurse, primary care)

Because of a high workload, participants could not allocate sufficient time for appointments with patients with COPD, often due to their comprehensive and complex needs. Participants emphasised the importance of acknowledging patients with COPD and their healthcare needs by structuring interventions focused on COPD.

Individual professional responsibility

Interprofessional collaboration and COPD management was believed to largely rely on the interest and motivation of individual healthcare professionals. For instance, participants expressed that further education was not prioritised by their managers despite the identified need for more COPD-related competence among healthcare professionals. Support from management was also experienced as missing concerning possibilities for developing routines for interprofessional collaboration.

The employer does not have the opinion that we should cooperate here…but (they believe that) you help them [patients] in the acute phases…and that it will be somehow good with that… (Nurse, primary care)

Consequently, the responsibility for increased competence and developing own routines was perceived to be placed on the individuals themselves. It was considered crucial that enthusiastic individuals were driving forces in developing and facilitating COPD-related collaboration with other healthcare professionals. Individual interest and commitment were seen as important cornerstones, but support from employers was desirable to have the strength to continue to make improvements. It was considered hard work to influence the development of routines and the organisation itself could be an obstacle.

Responsibility placed on a silent patient group

Patients with COPD were described as a ‘silent’ patient group who rarely contacted healthcare other than in cases of clear deterioration. Often, they also made contact for reasons other than their COPD, which led to healthcare professionals failing to capture information about the COPD disease and its impact on the patients. Patients with COPD were described as patients with low confidence in their own ability, who place few requirements on healthcare and who are used to being reprimanded for their smoking.

Many [patients with COPD] think that the shame is on them …and they don’t want to complain that much. (Nurse, primary care)

Still, participants described how responsibility was often placed on patients to contact healthcare themselves. For instance, after inpatient exacerbation care, the patients had the responsibility themselves to contact primary care for follow-up. This was confirmed by the perceived low numbers of referrals and overreporting between different levels of care.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first study to explore how nurses and physical therapists experience their role in interprofessional collaboration in the care delivery pathway between specialised care, primary care and long-term care. The results highlighted engaged nurses and physical therapists who were interested in working with patients with COPD. However, they experienced several insufficiencies that became barriers to interprofessional collaboration and smooth transitions in the care delivery pathway. Insufficient resources, routines, support and competence led to a care delivery pathway that was experienced as fragmented to a large extent. The nurses and physical therapists had a desire to work on interprofessional collaboration, since it was perceived to facilitate a holistic view of the patient and provide a more preventive focus in healthcare services.

Participants in the present study emphasised the importance of collaboration within and between levels of care to provide individualised interventions for people with COPD to prevent deterioration. Individualised assessment and interventions are recommended in treatment guidelines for COPD [Citation2,Citation4,Citation11] and important in the collaboration between different professions and levels of care [Citation29]. The holistic view of the patient that could come from interprofessional collaborations was reported by participating healthcare professional in the present study as especially important in older, frail patients with COPD with multimorbidity. Sandelowsky et al. [Citation18] concluded that physicians’ management of COPD patients with multimorbidity in primary care is insufficient and that there is a need for interprofessional collaboration to support these patients. Interprofessional collaboration has been stated as a key component in the management of frail patients, along with a close collaboration between different levels of care [Citation30]. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a comprehensive individualised intervention based on patient assessment and provided by an interprofessional team [Citation4]. However, since access to pulmonary rehabilitation for patients with COPD is low [Citation20,Citation31], several strategies are needed to enhance implementation in clinical care [Citation32].

Inadequate communication was revealed in the present study as a barrier to the collaboration desired within and between levels of care – something which has also been indicated in previous studies [Citation13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation33]. Karam et al. [Citation29] identified communication as a key component for collaboration within and between different healthcare organisations. Shared goals and a common purpose have been emphasised as essential for a successful collaboration between different organisations [Citation29]. Participants in the present study described unclear routines for communication between levels of care, leading to a large variation in how contact was made, which has also been reported in previous research [Citation33]. A common infrastructure for exchanging information has been suggested to improve communication and thereby enhance trust, clarify professional roles and support shared values among those involved [Citation29]. In addition to inadequate communication, limited competence was raised as a barrier to collaboration. Previous studies have also reported how limited knowledge about the disease and the contributions of other professions inhibit interprofessional collaboration in COPD management [Citation16–18]. Educating healthcare professionals is essential in enhancing implementation of pulmonary rehabilitation and interprofessional collaboration [Citation32]. COPD education programs for healthcare professionals can increase knowledge about the contributions of other professions and facilitate discussions about COPD between professions [Citation34]. Further studies are needed to develop and evaluate strategies for successful implementation of guidelines for collaboration within the care delivery pathway.

Similar to our study, previous studies have revealed experiences of fragmented COPD management in healthcare [Citation16,Citation17,Citation33], where the lack of routines and structure, together with unclear responsibility distribution both within and between levels of care, were presented as barriers to interprofessional collaboration. People with COPD and their relatives have advocated for introducing coordinators in COPD care, a contact person who can request and coordinate healthcare services from different levels of care [Citation14]. In the present and previous studies, the COPD nurse has been described as an important coordinator within COPD care, a person who takes responsibility for contacts with the patient and other professions [Citation16,Citation17,Citation35–37]. In other studies, the family physician has been described the same way [Citation33]. At the same time, the role of the physical therapist in COPD care was partly experienced as unclear by participants in the present study. In a previous study, it was reported that physical therapists were mainly contacted based on assessments of other professions [Citation16]. Thus, if other professions are unsure of the contributions of physical therapists, this will be a barrier for them when it comes to involving physical therapists in interprofessional collaboration and patients may not receive the support for physical activity and exercise that is recommended in treatment guidelines [Citation4,Citation11].

Local routines and structures have been shown to influence the availability of physiotherapeutic interventions in COPD care [Citation37–39]. A previous study in Swedish primary care reported high availability of healthcare professionals. At the same time, almost one quarter of the primary care centres had no access to evidence-based interprofessional rehabilitation for patients with COPD [Citation31]. Formalising collaboration and clarifying responsibilities, as well as allocating adequate resource support is important for interprofessional collaboration [Citation29,Citation34,Citation40]. In fact, interprofessional collaboration has been indicated to improve healthcare professionals’ adherence to treatment guidelines [Citation41].

Cultural status beliefs about social differences can lead to inequalities in society and in healthcare; so called ‘status bias’ [Citation42]. In the present study, participants reported that patients with COPD had low status in healthcare in favour of other diagnoses such as diabetes. This has also been reported in other studies among patients with COPD and healthcare professionals [Citation15,Citation16]. When healthcare professionals ranked diseases according to prestige, the result showed that low prestige diseases and specialties were associated with chronic conditions and elderly patients [Citation43,Citation44]. However, COPD was not an option in those lists. Furthermore, low ranking of conditions was associated with shame and blame [Citation44]. There is a risk that if patients with COPD perceive others as treating them according to low status, they will take this into account in their own behaviour [Citation42], and as described in the present study, remain silent. There is reason to consider status bias in the future, in the same way that gender bias, socio-economic status and ethnicity are considered today, with the goal of reducing or removing inequalities in healthcare [Citation45].

Methodological considerations

When conducting this study, we have strived to achieve trustworthiness [Citation25] in several ways. First, to achieve credibility [Citation25], we included participants from various settings with large variations in experiences and from both larger and smaller hospitals and cities. A weakness in the study is that, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, we had difficulties recruiting nurses from specialised care. Nonetheless, since several of the participants had experience from several levels of care, we believe that the interviews covered the perspectives of both nurses and physical therapists, as well as all three levels of care. It could be argued that eleven interviews were too small a sample to cover the aim of the study. In qualitative content analysis, it is important to achieve variation in content and multiplicity, which makes the selection of participants important [Citation24]. Considering the participants’ experiences from several levels of care and that the last interviews did not add any major new information to the analysis we determined that eleven interviews were enough. The aim of this study was to explore the perspectives of nurses and physical therapists, since they have such central roles in COPD care [Citation2,Citation4,Citation11,Citation16,Citation17]. Still, findings from our study are similar to findings in previous studies about COPD care in general, which included also other professions [Citation13,Citation16,Citation17,Citation33,Citation38]. However, future studies should also in depth highlight experiences from other professions such as dieticians, occupational therapists and physicians, as well as nurses and physical therapists in other contexts.

All interviews in the present study were conducted via telephone, which was chosen due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the geographical distance between participants. Telephone interviews have been suggested to be as valuable as face-to-face interviews [Citation46,Citation47]. Using telephone interviews can facilitate participation and the method is simple and relaxed when the focus is on the voice and the participant is not influenced by faces or gestures by the interviewer [Citation46,Citation47].

To avoid increasing the participants’ already heavy workload due to the COVID-19 pandemic, participants were not asked to comment on neither interview transcripts nor the findings. Member-checks – i.e. sharing transcriptions or findings with participants – have also been discussed as complex and controversial in previous literature. The discussion concerns what the actual benefit of member-check is versus its potential harm and how to handle the potential feedback the researcher receives from the participants. Instead, other procedures to attain credibility could be used, such as the triangulation between researchers within the research group that was used in this study [Citation48].

Dependability [Citation25] was strived for by using an interview guide for all interviews and by conducting the interviews for a limited period of time. ÅW, who conducted all interviews, has extensive experience as a physical therapist in long-term care. To ensure that her experience did not influence the data collection and analysis, frequent and regular discussions were performed between the three researchers who have various backgrounds and perspectives: both insider and outsider perspectives. To achieve transferability [Citation25], guidelines for reporting qualitative research have been followed [Citation28].

The data collection for this study was conducted between October 2020 and January 2021, a period much affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. In Sweden, no lock down was issued, but during this period citizens in Sweden were recommended to avoid public places, such as shopping malls, gyms and take public transportation because of high infection rates. These high infection rates caused a big strain on the healthcare system, which might have influenced participants’ answers during the interviews. Although, considering that many of our findings are consistent with findings from studies from before the pandemic and from other countries, we believe that they are also valid after the pandemic.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the experiences of nurses and physical therapists in Sweden regarding the care delivery pathway between primary care, specialised care and long-term care and the interprofessional collaboration for patients with COPD. Nurses and physical therapists were engaged in the care of patients with COPD and perceived that interprofessional collaboration could improve the quality of care. However, the collaboration between different professions and levels of care in the care delivery pathway showed several insufficiencies, such as the absence of organisational support, insufficient competence and low prioritisation of COPD. It is crucial to improve interprofessional collaboration and provide a smooth transition in the care delivery pathway. Several actions are needed, such as additional education to improve COPD-related competence and attitudes among healthcare professionals, the development and clarification of routines and enhanced conditions and opportunities for improved communication between healthcare professionals.

Ethical approval

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Swedish Ethical Review Authority reviewed the study protocol and had no ethical remarks. The study was deemed not to require any formal ethical approval since it didn’t deal with any sensitive personal data (Dnr 2020-04623). All participants received written and oral information about the study. They were informed that participation was voluntary, that they could choose whether they answered the questions or not, and that they could cease participation in the study at any time without providing a reason. Furthermore, they received information that all interview transcripts were coded and that the code key was kept locked away from the empirical data. All participants sent their signed informed consent by mail to the responsible researcher (SL) before the interviews.

Authors’ contributions

The study was conceived and designed by authors SL and ÅW. ÅW was responsible for data collection and the coding process. All authors were involved in the categorising and interpretation of the results. ÅW wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

| Abbreviations | ||

| COPD: | = | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| M: | = | Man |

| N: | = | Nurse |

| PT: | = | Physical therapist |

| RPT: | = | Registered physical therapist |

| W: | = | Woman |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the nurses and physical therapists who contributed to this study with their valuable time and experiences. Furthermore, we acknowledge Professor Karin Wadell at the Department for Community Medicine and Rehabilitation at Umeå University, Sweden for support funding for the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Box 1. Interview guide used in the individual interviews.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Celli B, Fabbri L, Criner G, et al. Definition and nomenclature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: time for its revision. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;206(11):1317–1325. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202204-0671PP.

- Global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease, global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report; 2024; [accessed 2024 Apr 22]. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

- Agusti A, Soriano JB. COPD as a systemic disease. COPD. 2008;5(2):133–138. doi: 10.1080/15412550801941349.

- Spruit MA, Singh SJ, Garvey C, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: key concepts and advances in pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(8):e13–e64. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1634ST.

- Garcia-Aymerich J, Lange P, Benet M, et al. Regular physical activity reduces hospital admission and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a population based cohort study. Thorax. 2006;61(9):772–778. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.060145.

- MacLeod M, Papi A, Contoli M, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation fundamentals: diagnosis, treatment, prevention and disease impact. Respirology. 2021;26(6):532–551. doi: 10.1111/resp.14041.

- Choudhury G, Rabinovich R, MacNee W. Comorbidities and systemic effects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med. 2014;35(1):101–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2013.10.007.

- Cazzola M, Bettoncelli G, Sessa E, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2010;80(2):112–119. doi: 10.1159/000281880.

- Miller J, Edwards LD, Agustí A, et al. Comorbidity, systemic inflammation and outcomes in the eclipse cohort. Respir Med. 2013;107(9):1376–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.05.001.

- Giacomini M, DeJean D, Simeonov D, et al. Experiences of living and dying with COPD: a systematic review and synthesis of the qualitative empirical literature. Ontario Health Technol Assess Ser. 2012;12:1–47.

- Socialstyrelsen (The National Board of Health and Welfare), Nationella riktlinjer för vård vid astma och kol. Stöd för styrning och ledning. (National guidelines for treatment of asthma and COPD. Support for governance and management.); 2020 [accessed 2023 Oct 9]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/nationella-riktlinjer/2020-12-7135.pdf

- Poot CC, Meijer E, Kruis AL, et al. Integrated disease management interventions for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9(9):Cd009437. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009437.pub3.

- Kayyali R, Odeh B, Frerichs I, et al. COPD care delivery pathways in five European Union countries: mapping and health care professionals’ perceptions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2831–2838. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S104136.

- Wodskou PM, Høst D, Godtfredsen NS, et al. A qualitative study of integrated care from the perspectives of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and their relatives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):471. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-471.

- Lundell S, Wadell K, Wiklund M, et al. Enhancing confidence and coping with stigma in an ambiguous interaction with primary care: a qualitative study of people with COPD. COPD. 2020;17(5):533–542. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2020.1824217.

- Lundell S, Tistad M, Rehn B, et al. Building COPD care on shaky ground: a mixed methods study from Swedish primary care professional perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):467. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2393-y.

- Lundell S, Pesola UM, Nyberg A, et al. Groping around in the dark for adequate COPD management: a qualitative study on experiences in long-term care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1025. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05875-2.

- Sandelowsky H, Natalishvili N, Krakau I, et al. COPD management by Swedish general practitioners - baseline results of the PRIMAIR study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2018;36(1):5–13. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2018.1426148.

- Janlöv N, Blume S, Glenngård AH, et al. Sweden. Health system review. Health systems in transition; 2023 [accessed 2024 May 3]. Available from: https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/publications/i/sweden-health-system-review-2023

- Desveaux L, Janaudis-Ferreira T, Goldstein R, et al. An international comparison of pulmonary rehabilitation: a systematic review. COPD. 2015;12(2):144–153. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.922066.

- Wei H, Horns P, Sears SF, et al. A systematic meta-review of systematic reviews about interprofessional collaboration: facilitators, barriers, and outcomes. J Interprof Care. 2022;36(5):735–749. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2021.1973975.

- Harvey G, Kitson A. PARIHS revisited: from heuristic to integrated framework for the successful implementation of knowledge into practice. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):33–33. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0398-2.

- Ryan F, Coughlan M, Cronin P. Interviewing in qualitative research: the one-to-one interview. Int J Ther Rehabil. 2009;16(6):309–314. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.6.42433.

- Graneheim UH, Lindgren B-M, Lundman B. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: a discussion paper. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;56:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M, et al. Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi-structured interview guide. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(12):2954–2965. doi: 10.1111/jan.13031.

- ICT services and system development and division of epidemiology and global health; 2015, Opencode 4.03; [accessed 2023 October 9]. Available from: https://www.umu.se/en/department-of-epidemiology-and-global-health/research/open-code2/

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Karam M, Brault I, Van Durme T, et al. Comparing interprofessional and interorganizational collaboration in healthcare: a systematic review of the qualitative research. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;79:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.11.002.

- Harrison JK, Clegg A, Conroy SP, et al. Managing frailty as a long-term condition. Age Ageing. 2015;44(5):732–735. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afv085.

- Arne M, Emtner M, Lisspers K, et al. Availability of pulmonary rehabilitation in primary care for patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study in Sweden. Eur Clin Respir J. 2016;3(1):31601. doi: 10.3402/ecrj.v3.31601.

- Rochester CL, Vogiatzis I, Holland AE, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society policy statement: enhancing implementation, use, and delivery of pulmonary rehabilitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(11):1373–1386. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-1966ST.

- Hartford W, Asgarova S, MacDonald G, et al. Macro and meso level influences on distributed integrated COPD care delivery: a social network perspective. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):491. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06532-y.

- Nyberg A, Lundell S, Pesola U-M, et al. Evaluation of a digital COPD education program for healthcare professionals in long-term care – a mixed methods study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:905–918. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S353187.

- Lisspers K, Johansson G, Jansson C, et al. Improvement in COPD management by access to asthma/COPD clinics in primary care: data from the observational pathos study. Respir Med. 2014;108(9):1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.06.002.

- Weldam SW, Schuurmans MJ, Liu R, et al. Evaluation of quality of life instruments for use in COPD care and research: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(5):688–707. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.07.017.

- Sandelowsky H, Krakau I, Modin S, et al. COPD patients need more information about self-management: a cross-sectional study in Swedish primary care. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2019;37(4):459–467. doi: 10.1080/02813432.2019.1684015.

- Sandelowsky H, Hylander I, Krakau I, et al. Time pressured deprioritization of COPD in primary care: a qualitative study. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2016;34(1):55–65. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2015.1132892.

- Henoch I, Strang S, Löfdahl CG, et al. Management of COPD, equal treatment across age, gender, and social situation? A register study. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2681–2690. doi: 10.2147/copd.S115238.

- Seckler E, Regauer V, Rotter T, et al. Barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of multi-disciplinary care pathways in primary care: a systematic review. BMC Fam Pract. 2020;21(1):113. doi: 10.1186/s12875-020-01179-w.

- Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, et al. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):Cd000072. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3.

- Ridgeway CL. Why status matters for inequality. Am Sociol Rev. 2013;79(1):1–16. doi: 10.1177/0003122413515997.

- Album D, Westin S. Do diseases have a prestige hierarchy? A survey among physicians and medical students. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(1):182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.07.003.

- Grue J, Johannessen LE, Rasmussen EF. Prestige rankings of chronic diseases and disabilities. A survey among professionals in the disability field. Soc Sci Med. 2015;124:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.044.

- Phelan JC, Lucas JW, Ridgeway CL, et al. Stigma, status, and population health. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.004.

- Novick G. Is there a bias against telephone interviews in qualitative research? Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(4):391–398. doi: 10.1002/nur.20259.

- Vogl S. Telephone versus face-to-face interviews: mode effect on semistructured interviews with children. Sociol Methodol. 2013;43(1):133–177. doi: 10.1177/0081175012465967.

- Goldblatt H, Karnieli-Miller O, Neumann M. Sharing qualitative research findings with participants: study experiences of methodological and ethical dilemmas. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(3):389–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.12.016.