ABSTRACT

Urban issues have been under the policy attention of the European Union (EU) from the late 1980s. Its influence has been particularly significant in countries that had not developed an explicit urban national policy. This is the case of Spain, in which specific instruments aimed to address urban challenges co-funded by the Structural Funds have been developed over the last four programming periods of the Cohesion Policy. These instruments have been the following: URBAN (1994–99); URBAN II (2000–06); the Iniciativa Urbana (IU) (2007–13); and the Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (ISUDS/EDUSI) (2014–20). So far they have been the only explicit initiatives of urban regeneration that have operated at a national scale in the country. This fact, together with the sustained experience in implementing these kinds of instruments, points to Spain being an interesting case study in which to understand the evolution and contribution of the urban dimension of Cohesion Policy from 1994 to the present. In this context, the IU emerges as particularly relevant because it has worked as a nexus between the two rounds of URBAN and the ISUDS that are currently being implemented. It is also relevant because it continued the implementation of the URBAN method in Spain explicitly through 46 programmes of urban regeneration that were developed in all the regions (Autonomous Communities), something that did not happen in any other member states in the period 2007–13. Building on the literature on the contribution of URBAN to the practice of urban regeneration in the country, this study develops an in-depth analysis of the IU. The research has allowed the identification of the relevant lessons aimed to inform the implementation of the 173 ISUDS that are being developed at present in Spanish cities. These lessons can also contribute to the Spanish Urban Agenda (in progress) and, at the EU level, to the definition of the urban dimension of Cohesion Policy for the post-2020 period and its implementation in the member states.

JEL CLASSIFICATIONS:

INTRODUCTION

Urban issues have been subject of policy attention by European Union (EU) institutions from the end of the 1980s. In that period the dimension of urban decay in the neighbourhoods of many cities led to the review of the effect that the action implemented with the support of the Structural Funds was having in urban areas. This new concern, along with the increased demands on the part of cities and cities’ associations, and the publication of two key reports (the Cheshire Report of Citation1988 and the Parkinson Report of Citation1992) raised an awareness about the necessity of putting into place specific instruments (Hall, Citation1987) to support municipalities in fighting urban decay through a vision aimed to overcome sectoriality. This idea was present in the Fourth Environmental Action Programme (1987–92) of the European Economic Community (EEC) that stated that ‘one priority will be to consider to what extent the Community’s existing Structural Funds (and notably the European Regional Fund) could be directed to comprehensive environmental programmes in inner city areas’ (European Commission (EC), Citation1990, p. 2). It was further developed through the Green Paper on the Urban Environment published by the EC (Citation1990), acknowledging that also other areas of European cities needed the ECC’s support to fight urban decline. One result of this policy attention was the launch in 1989 of the Urban Pilot Programmes (UPP) that can be considered the instrument that anticipated and tested the method of urban regeneration that was finally embedded in the URBAN Community Initiative (launched by the EC in 1994). It was deployed through two consecutive rounds: URBAN (1994–99) and URBAN II (2000–06). With the UPP and URBAN, the Cohesion Policy allocated for the first time specific funds to tackle urban decline through urban regeneration programmes. From that moment the EU has developed a policy action shaped by the definition and deployment of instruments of different nature. They have consisted mainly of programmes for urban regeneration, studies and research, dissemination of good practices, and supporting innovative projects (Atkinson, Citation2007, p. 2), policy documents, and the construction of networks of cities around different urban challenges (the URBACT programme) (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2017b). Note that this activity has taken place in a policy field in which, under the EU Treaty, the EU has no formal responsibility (Parkinson, Citation2005).

There is consensus to point out that URBAN has been the more explicit and specific urban tool launched and developed so far or, as Van den Berg, Braun, and Van der Meer (Citation2007) expressed it: it has been ‘probably the most city-oriented programme of the European Commission’ (p. 51). Its effect has been considered positive by many and different stakeholders: EU institutions (e.g., EC, Citation2006,Footnote1 2009;Footnote2 European Parliament, Citation2009Footnote3), the Informal Meeting of Ministers on Urban Development of the EU (Citation2010, pp. 4–5); the Academia (e.g., Carpenter, Citation2011; Frank, Holm, Kreinsen, & Birkholz, Citation2006Footnote4), and other actors (Urban Future, Citation2005Footnote5). At the level of the EU, it has contributed importantly to the Urban AcquisFootnote6 of the EU and the ‘urban mainstreaming’ adopted in the framework of the Cohesion Policy for the period 2007–13 (EC, Citation2008a). It can also be considered that URBAN has been instrumental in achieving the current level of commitment of the EU institutions and member states (MS) with urban matters. It has contributed to constructing the path that has led to the signature of the Pact of Amsterdam in 2016 for the advancement towards the Urban Agenda for the European Union (currently in progress). Also, the literature that analyzes Europeanization in the context of urban matters mentions URBAN as a relevant instrument (Carpenter, Citation2013; Dukes, Citation2008; González Medina & Fedeli, Citation2015; Tortola, Citation2016).

The influence of URBAN has also been considered positive in the MS,Footnote7 particularly in those that had not developed an explicit urban national policy (Carpenter, Citation2013). The literature has demonstrated its capacity to introduce innovation into the field of urban regeneration in those countries, impacting particularly the modes of urban governance of the participating cities (Frank et al., Citation2006, p. 134) and the partnership working (Carpenter, Citation2011). This is because the so-called URBAN method (EC, Citation2003, p. 7), or ‘URBAN approach’ (Atkinson, Citation2014), is based on a vision of urban regeneration that integrates the following main elements/aspects:

Area-based approach.

Strategic character implemented through the definition of clear objectives to be achieved in a seven- to eight-year horizon.

Integrated approach that addresses the physical, environmental, social, economic and governance dimensions of urban decline.

Partnership vision in which institutions, business, the entities of civil society and the citizens contribute with their ideas and capacity to the process of regeneration.

Collaborative approach between the different areas of local government and between government levels (so that the EU, national, regional and local actions are aligned).

Added value of the measures proposed, so that they deliver demonstrative results (to be replicated in the same local context, but also to be transposed to other local realities).

Competitive call that promotes, among other issues, the quality of the strategy of urban regeneration, the adequateness to the eligibility criteria and the funding complementarity.

In Spain, the literature has shed a light on the positive contribution of the two rounds of URBAN. It worked as a transformation driver of urban regeneration in the country, introducing an innovative approach that was able to transform the national and local policy discourse in this regard. It also influenced the policy action of some regions (Autonomous Communities) (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2012a). Moreover, the lack of a national policy on urban regeneration encouraged the perception of URBAN as a reference to be followed by cities ‘given the lack of a methodological approach … of urban regeneration provided by the upper levels of government’ (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2017a, p. 405).

Even if, as mentioned, the results of the two rounds of URBAN were considered positive, the Cohesion Policy adopted the ‘urban mainstreaming’ vision for the period 2007–13 (EC, Citation2008a), and URBAN disappeared. In that period the ‘guiding principles of the URBAN programme’ had to be integrated into the Operational Programmes proposed by the MS and co-financed by the Structural Funds (EC, Citation2008b, p. 12; Citation2009a). Beyond this, the approach included the incorporation of a regulatory provision in the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) regulation (Article 8) that allowed MS to fund the development of initiatives of urban regeneration taking URBAN as a reference to continue its experience. It was set as a non-mandatory provision.

As a result of the finalization of URBAN and also of the way in which the MS implemented the ‘urban mainstreaming’ envisaged by the EC, as many had feared (Atkinson, Citation2007), the urban dimension of EU policy lost visibility in the different national contexts (Atkinson, Citation2014). This was because ‘in some MS, perhaps the majority, the approach implemented by the URBAN Initiatives was lost or became blurred’ (Atkinson, Citation2014, p. 6). One reason that explains this is the insufficient use by MS of Article 8 of the ERDF regulation for the continuation of the URBAN experience. In fact, the EC (Citation2008a) identified that only five of the 119 Operational Programmes under the Convergence Objective of Cohesion PolicyFootnote8 used that regulatory provision, while 40 of 115 Operational Programmes under the Regional Competitiveness and Employment ObjectiveFootnote9 referred to it. The document also mentioned that ‘URBAN-type’ actions were mostly programmed at the regional level, which also explains why the urban dimension of EU policy lost visibility at the national level during that period. Nevertheless, a minority of MS ‘chose to introduce a stronger national approach’ (EC, Citation2008a, p. 20). In this regard, the document pointed out the development of a national initiative in Spain, called Iniciativa Urbana (IU) and the Urban Priority Axis formalized in the Romanian Regional Development Operational Programme. The Spanish case was the only one in which the Operative Programmes of all the regions made use of Article 8 under the umbrella of the mentioned national initiative giving continuity to the URBAN method (De Santiago, Citation2017, p. 30). Because of all this, the Spanish case emerges as particularly relevant. Its interest also relies on the fact that the IU allowed a continuation of the experience of URBAN and URBAN II in the country, and the development of the knowledge on which the government has based the definition of the so-called Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (ISUDS) for the period 2014–20. In fact, the IU has been crucial for the continuation of the implementation of specific urban programmes funded along four consecutive programming periods of the Cohesion Policy:

1994–99: URBAN Community Initiative.

2000–06: URBAN II Community Initiative.

2007–13: Iniciativa Urbana (IU).

2014–20: Estrategias de Desarrollo Urbano Sostenible Integrado (EDUSI)/Integrated Sustainable Urban Development Strategies (ISUDS).

This continuity has not taken place in other MS and makes the Spanish a significant case in which to understand the impact of EU urban policy and to bring about conclusions on how it has worked. The continuity of the implementation of the ‘URBAN principles’ for almost 25 years through the mentioned instruments explains the transformative capacity of the urban policy of the EU in Spain (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2017a). It can also be explained because these have been the only instruments of urban regeneration launched at the national level so far (as the country does not have an explicit national urban policy). In this framework, the IU emerges as particularly relevant because it has contributed importantly to root the URBAN approach, and has worked as a nexus between the URBAN Community Initiative and the current ISUDS approach. All this, along with the lack of similar experiences in other MS during the period 2007–14, shows the relevance of focusing on this instrument to understand how the vision enshrined in the urban dimension of Cohesion Policy for the period 2007–14 was implemented and what lessons emerge from it. In Spain, these lessons will be relevant in the framework of the development of the 173 ISUDS (EDUSI) that are currently in progress. The knowledge achieved can also contribute to informing the decisions that will be taken regarding urban matters at the EU level for the post-2020 period as well as regarding the process of construction of the Urban Agenda for the EU.

From all these considerations, this work has the objective of analyzing the IU to shed a light on how it embedded the main principles of the URBAN method. For that, the study has addressed the process of definition of the call of the IU (developed by the Spanish government) and the definition of the programmes of urban regeneration selected under the two IU calls.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section explains the methodology. The third section presents and analyzes the scenario in which the urban policy framework of the EU for the period 2007–13, combined with the specific interest on urban issues of the Spanish government at that time, made possible the launch of the IU. The fourth section focuses on the programmes selected within the IU and presents the results of the analysis. The fifth section concludes.

METHODOLOGY

The analysis of the IU has been developed through a qualitative mixed approach that integrates in an iterative way the review of the literature and other relevant sources (mainly primary sources and grey literature) with the consultation to public servants (who work in the institutions responsible for managing the IU), and the attendance at relevant events in which the managing authority of the IU at a national level (the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios of the Ministry of Finance) informed yearly some specific stakeholders about the advancement of this instrument and presented and introduced the ISUDS/EDUSI callsFootnote10 at the beginning of the period 2014–20. The objective of this mixed approach was aimed: (1) to setting the basis for the construction of a protocol for the study the of all the IU programmes – the protocol had to be able to analyze homogeneously how the IU introduced and adopted the URBAN approach in all the programmes; and (2) gathering the necessary information to understand the process of construction of the IU call, and the approach of the strategies prepared by the cities that were selected in the framework of the two calls of the IU. This had to be done taking into account that the process under study was an ‘ongoing’ policy process.

The literature reviewed was the following:

Literature and primary sources in which EU institutions and academics defined the main elements of the URBAN method and the Urban Acquis of the EU.

The scientific literature in which different authors analyze the development of the urban policy of the EU in Spain (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2009, Citation2012a, Citation2017a; García Jaén, Citation1998; Gutierrez Palomero, Citation2009, Citation2010; Huete, Merinero, & Muñoz, Citation2014; Rodriguez Álvarez, Citation2005).

Primary sources in which the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios (Ministry of Finance)Footnote11 defined the IU call and set the guidelines for the implementation of the IU programmes of urban regeneration.

Proposals developed by cities to access the IU through the two calls (2007 and 2008). These documents were provided by the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios. The programmes of Ceuta and Melilla could not be analyzed as they could not be accessed by the research. In total, the study addressed 44 of the 46 programmes developed under the IU.

Presentations and discursive information provided in the context of the events attended and mentioned above. The attendance at the mentioned events permitted one to put in place the observatory participation method. It, together with the conversations with the officials of the ministry, permitted one to fill information gaps on the ongoing policy process. The observatory participation consisted of registering the information and categorizing it according to its relevance for the study.

The review undertaken provided a solid knowledge of the IU and the analytical framework that allowed the establishment of the protocol for the analysis of the IU programmes. Note that this study is framed in the context of a wider research work that proposed an initial protocol to address in-depth case studies of IU programmes (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2017a). That can be considered a previous step of this research that has led to the protocol presented here. This instrument evolved had to be able to address the high number of programmes that entered the IU systematically and be based on the definition of five analytical categories that address five key aspects of the so-called URBAN method or URBAN approach that characterized the IU and that are considered particularly relevant because of the potential contribution that they can make to the Spanish scenario:

Coherence of the IU programmes with the regional development priorities and strategies. This category was introduced in the study in order to analyze the multilevel governance of the IU, particularly to study the regional/municipal interface that is crucial in the context of urban policies in Spain. This is because regions and cities have most of the competences on urban matters.

Municipal interdepartmental governance. This category addressed explicitly the level of coordination and collaboration among the municipal departments responsible for managing different measures of the IU programmes in order to make possible the integrated approach of the URBAN method.

Intersectoriality of the strategies. This category has the objective of understanding the level of integration of environmental, social, economic and governance measures within the strategy of urban regeneration of each IU programme. Categories 2 and 3 together provide a good insight into the integrated approach adopted by the programmes of the IU.

Participation processes and mechanisms. This category studies the dimension of participation in the governance model applied by the programmes, aiming to understand to what extent a sustained and solid participative process was included in the programmes. It looks at the provision of arenas of participation, a method of participation based on clear rules, as well as funds and technical resources for the same.

Innovative approach of the programmes. This category builds on the previous categories and aims to understand the level of innovation assumed by the programmes. It looks particularly at the discourse on innovation assumed by the documents prepared by cities to access the IU, and the approach they adopted in a specific part of such documents entitled ‘Innovative character of the project’ (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007b, p. 8).

The analysis of the proposal of the IU consisted mainly of an in-depth analysis of the document presented by each selected city to access the IU. These documents were considered crucial to the study because they described in detail the strategy of urban regeneration designed by each city. This strategy had embedded in it the adoption (or not) of the URBAN principles. Because the study aimed to understand how these had been integrated into the IU (and not how they had been implemented), it was decided to focus only on the proposals and not on the documents that could provide information on their results.

THE DEFINITION AND LAUNCH OF THE URBANA INICIATIVA (2007–13) IN THE GENERAL SPANISH SCENARIO

One objective of the Cohesion Policy for the 2007–13 period was to enhance its urban dimension (EC, Citation2006, p. 3). On this basis, significant changes were introduced. The main one was the adoption of the ‘urban mainstreaming’ (EC, Citation2008a) into the Cohesion Policy. This entailed that the URBAN Community Initiative had to be mainstreamed in the Operational Programmes of the Member States and the regions (EC, Citation2008a). According to Atkinson (Citation2014, p. 6), ‘the intention was that all European cities would benefit from the lessons derived from URBAN and apply them to develop an integrated approach to urban areas’. As a consequence of the urban mainstreaming, the URBAN Community Initiative disappeared. This situation led many people to express concern regarding the ‘potential loss of a small (in terms of funds) initiative that had the advantage of explicitly concerning itself with urban areas and their problems’ (Atkinson, Citation2007, p. 4) and to point out the difficulties of mainstreaming the urban dimension of EU policy, underlying that few European countries had been successful in that in the past (Parkinson, Citation2005). Perhaps because of this, it was decided to include in the regulation of the ERDF (Regulation EC 1080/2006) Article 8 which allowed the MS continuing the implementation of urban regeneration programmes based explicitly on URBAN to access the financial support of this Structural Fund. This article, entitled ‘Sustainable Urban Development’, stated that the ERDF could support ‘the development of participative, integrated and sustainable strategies to tackle the high concentration of economic, environmental and social problems affecting urban areas’ (Official Journal of the EU, Citation2006, L210, p. 6). It is important to clarify that MS could use Article 8 voluntarily because it was not mandatory.

Spain demonstrated a committed interest to explore and implement that possibility. In fact, finally, it was one of the few MS that integrated this funding line in the so-called Marco Estratégico Nacional de Referencia 2007–2013 (MENR), the financial and strategic framework agreed with the EC in May 2007 (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007a). As a result, it was also integrated into the Operational Programmes of all the regions. This fact is very relevant, mainly because the analysis of the mainstreaming of the urban dimension in the period studied shows that in the majority of the countries the urban dimension of Cohesion Policy was implemented in a sectoral manner, resulting in the loss of visibility of the urban dimension. It was partly because cities had to apply for funds in the same way as other potential beneficiaries, without any guarantee that they would receive specific funds to address their problems in an integrated way (Atkinson, Citation2014, pp. 6–7). Nevertheless, in Spain, the implementation of Article 8 allowed the putting into place a specific urban initiative aimed at supporting cities to regenerate their most vulnerable areas through holistic strategies. It was called Iniciativa Urbana and was launched by the Ministry of Economy at the end of 2007 as an instrument that explicitly aimed to ‘continue the valuable experience obtained through the development of the URBAN Community Initiative’Footnote12 in the country (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007b, p. 1). As mentioned above, in the general EU framework described, the IU was an exception, only comparable with a few instruments launched by other MS.

To understand the contribution of the launch of the IU in the Spanish framework, it is essential to take into account that the Socialist Party, in government from 2004, had started an activity specifically aimed at redirecting urban policies. It was an attempt to introduce a new paradigm on urban development, able to face pressing environmental and social problems (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, Citation2004). This attention contrasted with the lack of interest on the matter that had characterized the period 1996–2004, giving place to a relevant and unusual policy activity by the Spanish government. It consisted mainly in the development of a relevant number of urban strategies and guideline documents, the introduction of the integrated approach of urban regeneration that characterized URBAN in the National Housing Plan, and also in the definition of the IU using the possibility offered by Article 8 of the ERDF (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2012b; De Gregorio Hurtado & González Medina, Citation2017). It is possible to affirm that this specific interest to urban policies was crucial for the definition of the IU.

The IU was launched through two calls: the first at the end of 2007 and the second at the end of 2008. The calls consisted of two main documents (a letter addressed to all the eligible cities and a document of guidelines). The second was aimed to support the municipalities in the process of preparation of their candidate programmes. Both documents were prepared by the body responsible for the management of the instrument at the national level (the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios of the Ministry of Finance). The IU was restricted to cities with a population over 50,000 inhabitants and to the provincial capitals (even if they were less populated). The document of guidelines mentioned precisely the aim of continuing the experience of URBAN, explaining that the strategies of urban regeneration had to adopt

an integrated approach regarding the development of a multidisciplinary set of actions (environmental, social, urban, economic, tourist, cultural, heritage, new technologies, information society, etc.) to address the problems of an urban area selected within the municipality and with a clear social and economic disadvantage compared to the rest of the city.Footnote13 (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citationundated, p. 1)

The call established the number of programmes to be financed in each region, defining a distribution of the economic resources that used as criteria the population and the Cohesion Policy objectives in which the Spanish regions were integrated for the period 2007–13. As a result, to access the IU, cities competed only with those of their regional framework, not with all the cities of the national territory as under URBAN and URBAN II.Footnote14 Consequently, all the regions and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla could develop at least one programme of the IU.

The call announced that the total number of programmes to be financed was 43, but finally, this was increased to 46. The programmes were selected by a mixed commission in which were represented all the ministries with relevant competences on the matter (Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Environment, Ministry of Public Works and Ministry of Housing) and the Spanish Federation of Municipalities and Provinces. The regions were consulted on the programmes to be selected in their territory, but they could not vote in the commission. This shows that the IU worked very similarly to URBAN in this regard, limiting the role developed by the regions, even if under the Spanish constitution they have relevant competences on urban regeneration. As in URBAN, better integration of the regions in the policy development process would have allowed them developing ‘in-house’ learning.

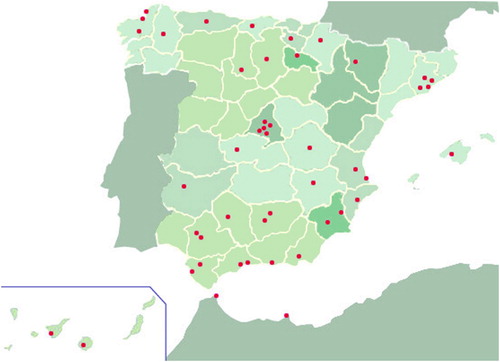

The IU calls took explicitly into account the EU guidelines of the Cohesion Policy for the period 2007–13 (European Council, Citation2006), and the recommendations of the Communication of the EC entitled Cohesion Policy and Cities: The Urban Contribution to Growth and Jobs in the Regions (EC, Citation2006; Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007a). As mentioned, 46 programmes were selected ().Footnote15

As established by the document of guidelines, the cities had to present to the call a strategy of urban regeneration based on a sound analysis and diagnosis of the vulnerable area they aimed to regenerate. It had to include a strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis. The strategy had to be integrated (putting into place social, economic and physical measures) and participative, involving the relevant stakeholders of the local community in the definition of the strategy and the implementation of the programme. The strategies to be developed had to take into account a set of priorities. Regarding that the document of guidelines mentioned that the programmes of the IU had to include specific parts explaining the following:

The strategy and the objectives of the programme.

How the programme would make possible the coordination with the local stakeholders.

The innovative character.

How the equal opportunities dimension was taken into account in the strategy.

The relationship of the programme with the strategy of regional development of its territory.

The structure and mechanisms for the management and monitoring of the programmes (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007b).

Figure 1. Distribution of the 46 programmes of the Iniciativa Urbana (IU) in Spanish provinces and regions (Autonomous Communities).

Source: Author.

The discourse adopted by the document of guidelines, as well as the issues to be addressed by the strategies, demonstrate that the IU was consistent with the URBAN method as well as with the Urban Acquis of the EU. The next section analyzes how the most relevant methodological elements of this method of urban regeneration were integrated into the 44 programmes of the IU:

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The results of the analysis are discussed here to grasp the level of uptake and understanding of the IU strategies according to the objective mentioned above in the introduction. This is done by addressing the five analytical categories defined in the methodology.

Coherence of the IU programmes with the regional development priorities and strategies

This aspect throws a light on the coherence between territorial priorities and strategies at a regional level and the proposals put forward by cities in the framework of the IU. It was a relevant issue within the general context of the urban policy of the EU 2007–13, as the multilevel governance approach had been explicitly reinforced by the Leipzig Charter: ‘Every level of government – local, regional and European – has a responsibility for the future of our cities’ (Meeting of Ministers on Urban Development of the EU, Citation2007, p.2). Consequently, it had also been addressed specifically as a priority by the document of guidelines for the preparation of IU programmes. It set that the candidate proposals had to explain how the strategy developed by the municipality addressed the relationship between such a strategy and the ‘strategy of regional development’ (Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007a, p. 7). The review undertaken by this study takes all this into account and aims to understand the level of coordination of the regional strategies with those of the IU prepared by the municipalities. This is considered an issue that presented an interesting potential, as Spanish regions can set legal and financial frameworks to foster urban regeneration in their territories. Nevertheless, few of them have developed specific policies, which explains why cities and regions do not have a ‘coordinated tradition’ of policy action on urban regeneration. As a result, the IU provided a scenario with the capacity of making regions and cities more aware of their interdependence in this regard.

The study has identified three different ways in which cities addressed this issue:

Municipalities that did not describe how their strategies were integrated or complementary with the regional development strategy, even if this was something requested by the IU’s call. This was the case for 18 of 43 programmes analyzed.

Municipalities that pointed out that their strategies were coherent with their respective Regional Operative Programmes,Footnote16 but did not mention the level of coordination with their respective regional development strategies (eight programmes). These cases are similar regarding the impact to the previous ones, as they do not look for concrete and specific ways to create synergies with the regional policy priorities.

Municipalities that integrated their strategies in their respective regional development strategies. This is the case for 17 IU programmes. In these cases the coherence with the regional strategies ranges from a good level of consistency to a superficial description on how the measures included in the programmes aligned with the main development priorities of the regional strategies.

The scenario of coordination between cities and regions described in the proposals also shows a low level of integration of upper levels of government in the process of design of the IU strategies. In a few cases it is mentioned that regions and provinces were invited to take part in it or are considered actors to be integrated in the future. The documents expressed that the regions participated in the definition of the strategy in the case of the programmes of Torrent and Murcia, and that they would be invited to participate during the lifespan of the programme in the case of the Hospitalet de Llobregat, Pamplona. The programme of Lugo mentioned that the province would play a relevant role within its strategy, as it would co-finance some of the measures to be implemented. Considering all this, it can be said that the IU was not successful in complementing ERDF funding with regional financial resources.

Municipal interdepartmental governance

The analysis of the IU proposals presented by the cities shows that the programmes were in all cases managed within the municipalities (not by external entities) and that all of them proposed a management structure aimed to sustain sound mechanisms of coordination among the different government areas involved in the implementation of the various measures. In all the cases the programmes identified a municipal department or body (in general an existing one) responsible for the coordination of the measures to be implemented. In this regard, this study has identified a relevant level of homogeneity in the relevance that the municipalities assigned to this issue and the level of definition of the managing structure and mechanisms, which in most cases is very detailed. As a result, this was an aspect widely addressed by the participant cities, revealing that they did not find limitations to give place to coordinating frameworks for the management of the programmes within the municipality and that they were successful in proposing consistent mechanisms to improve the horizontal dimension of governance (interdepartmental) within their proposals. The management of the programmes by the municipalities shed a light on the potential capacity of the IU to generate in-house learning.

Intersectoriality of the strategies

Cities participating in the IU foresaw the integration of a wide range of measures in different areas of action. The review of the programmes has allowed the identification of the following: improvement of the urban environment; new public facilities; waste reduction and management; universal accessibility; urban mobility and public transport; efficient use of energy and water; entrepreneurial activity and employment; commerce; tourism; research, culture/education; professional training; equal opportunities; social integration; urban safety; rehousing of citizens; information society; participation; management, control and monitoring; and information and advertising.

The analysis shows that all the programmes included measures of improvement of the urban environment and the construction of new public facilities, as well as measures of management, control and monitoring (). A relevant number of programmes included measures of waste reduction and management (24); entrepreneurial activity and employment (37); professional training (28), social integration (38) and equal opportunities (36). All this shows few differences if compared with the two rounds of URBAN analyzed by De Gregorio (2012). One relevant difference has to do with the inclusion of measures in some areas, particularly the one that deals with the integration of measures of energy efficiency, the introduction of renewable energy systems, consumption reduction and efficiency of water management. The same can be observed in the case of the measures regarding urban mobility, and gender equality (in the broader context of equal opportunities). Looking at the introduction of urban mobility, energy efficiency and the reduction of water consumption in some programmes (), it is possible to state that the proposals of some cities introduced in the integrated approach adopted the environmental vision that the URBAN and URBAN II programmes had not been able to develop. The observation of the integration of the gender perspective in the equal opportunities vision in some programmes also shows an advancement in the integrated approach, as from the Treaty of Amsterdam of the EU the gender perspective has to be mainstreamed in all EU policies (De Gregorio Hurtado, Citation2017b).

Regarding the inclusion of measures connected to the management of the programmes and their capacity to transform local governance, almost all the programmes (41) included measures for management, control and monitoring, and for the dissemination of their activity inside and outside their respective municipalities (measures of information and advertising (39)). Nevertheless, less than half introduced measures to implement a participation process (16). This is further analyzed below.

Note that an in-depth review of the measures introduced by most programmes in the mentioned ‘new’ fields shows that few of them were able to create synergies with other ‘sectoral’ measures. In fact, regarding the integration among measures, the review (undertaken by an analysis of the discourse developed in the documents and the measures included) allows one to state that the IU programmes did not advance in this regard if compared with URBAN II programmes. Municipalities continued fostering the measures of physical improvement and construction of new public facilities that were allocated a relevant amount of the total financial resources.

Participation process and mechanisms

The analysis reveals that most municipalities developed a process of dialogue between the different relevant stakeholders in the framework of the design of the strategy of the IU programmes. This shows the continuation of a positive trend that was incipient in URBAN II. It can be explained because the IU rules established as compulsory the local consensus on the strategy through the adoption of the programme by the political representatives of the municipalities (this had to be clearly stated in the letter presented by each municipality to access the IU; Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda, Citation2007b) and the explanation about how the local community would be involved in the programme. The first required a process of dialogue before the submission of the programme to the IU’s call. To give place to it, many cities used undergoing participative processes or existing participative arenas. This is something that did not happen in the framework of URBAN II and shows that participation was being adopted as a working method by Spanish cities. The processes or arenas used to create a consensus on the IU strategies were: the strategic plans of the cities (five cities), their neighbour councils (three cities),Footnote17 their Local Agenda 21 (two cities) or previous processes of urban regeneration (three cities). Some programmes mentioned that the experience achieved through the development of its Local Agenda 21 had been crucial to include the participative dimension in the programme (e.g., Burgos). In other cases, the municipalities mention in their documents that participation at that stage took place, but they did not explain how (10 cities). Some other cities did not mention this issue at all (six cities). At the other extreme, other cities put into place a specific process of dialogue to build a consensus (14 cities). In any case, the development of specific activities to promote dialogue among different stakeholders was not a guarantee of a robust participative process for the design of the strategy, as some cities mentioned that it consisted only of one participative meeting (e.g., Arona, Talavera de la Reina).

This analysis has also tried to understand if the strategies of the programmes included the definition of sustained areas of participation, their mechanisms and rules, and if they allocated economic resources within their budgets. The study has identified five different cases:

Programmes that integrated into their strategy the explanation of the process of participation to be undertaken, together with the definition of the arenas for participation, the frequency of the participative meetings, the rules for participation and (in most cases) the allocation of resources (10 cities). In general, these programmes were committed to understanding how local governance could be improved by applying a participative approach to the implementation and monitoring of the strategies. In some cases, participation was pointed out as a driver of innovation.

Programmes that defined the arenas for participation but did not explain how they would function and did not allocate specific economic resources to finance the participative mechanisms. Some created new arenas of participation (11 cities), while a minority used existing participative forums to implement participation within their programmes (two cities).

Programmes that seemed to understand participation as information to the local community and expressed that it would be developed along the lifetime of the programme (two cities).

Programmes that did not mention the way in which they intended to implement participation within their strategies (11 cities). Interestingly, most indicated in different parts of the document that participation is appreciated and considered, but it seems to be mentioned only as a means to enter the IU.

Just in few cases the programmes did not refer to participation (eight cities).

The review of the document of guidelines prepared by the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios allows one to identify that only the first group adopted the concept of participation embedded in the IU’s call. It was a concept of participation that understood it as a means to construct local capacity in the eligible area, and also in the broader context of the municipality. The analysis of this issue allows one to understand that the IU tried to foster the participative approach, taking into account the lessons showed by URBAN and URBAN II at the low level of adoption of this vision in the programmes. As a result, the IU introduced the obligation to adopt it. It is interesting to observe that the municipalities that ignored this were selected to access the IU’s funding.

Innovative approach in the programmes

This category aims to understand the level of innovation embedded in the programmes. Innovation is understood as the introduction in the strategies developed by cities of new approaches, as well as new areas of policy action, that were not present in the practice of urban regeneration previously.

This category has been addressed analyzing the part entitled ‘innovative character’ in the documents that cities presented to access the IU. That part was established by the IU’s call as compulsory, showing that the innovative capacity of the programmes was as relevant in the IU as it had been in the URBAN and URBAN II calls.

The review reveals that cities faced the definition of the innovative dimension of their strategies with different levels of commitment. It is possible to find documents in which this dimension was well explained and coherently integrated into the strategy (Palencia) and, on the contrary, cities that addressed it in a very general way, without providing concrete ideas on how innovation was present in their strategies (Hospitalet de Llobregat, Getafe, Mérida, Ferrol). There were also cities that did not include this compulsory part in the documents they developed to access the call (Cerdanyola del Vallès, Logroño). The rest of the documents developed this part pointing out in most cases that the innovative character of the strategy they proposed consisted in the participative and/or integrated approach that they adopted as recommended by the call. Cities extensively identified these two methodological elements of the URBAN method with innovative drivers within their proposals. In some cases, they also mentioned that innovation would take place if the method or urban regeneration they were putting into place (as recommended by the call) could be transferred to the policies and management practices within the municipality. In this regard, a minority of the documents mentioned the capacity of the approach adopted to transform local governance. The innovative value that the documents reviewed gave to participation is contradictory in many cases with the rest of the discourse embedded in their proposal, as in many cases they did not mention the creation of specific arenas of participation or other mechanisms to make it possible during the lifespan of the programme.

Regarding the review of the areas in which the documents developed by cities proposed to act (), it is relevant to point out again that many programmes proposed to act in fields in which they were not used to doing in the context of urban regeneration strategies. Particularly relevant are the number of cities (22) that decided to propose the implementation of measures consisting of the reduction of energy consumption and the reduction of water consumption, and sustainable mobility (32). These all are fields in which URBAN II programmes have not proposed to act, and reveal that cities are more aware of the necessity to decrease greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and manage better natural resources if they aim to advance towards more sustainable scenarios. In any case, even if this has to be considered an advancement, the review of the measures proposed revealed that frequently they consisted of small and disconnected actions that could not have the capacity to act as demonstrative experiences within the municipalities.

Table 1. Areas of action addressed by the different programmes of the Iniciativa Urbana (IU).

CONCLUSIONS

The analysis undertaken suggests that even if the IU has found limitations to embed all its potential into the strategies developed by cities, it has played a crucial role in continuing the consolidation of the experience introduced in Spain by URBAN and URBAN II. This is because it has been the first initiative of urban regeneration completely launched and designed by the Spanish government (URBAN and URBAN II were designed and launched by the EC, while the IU’s call was prepared by the Ministry of Finance with the support from other ministries). This is a fundamental innovation driver in a country that does not have an explicit urban policy. Moreover, this instrument was defined and launched in a policy context in which the implementation of explicit instruments for sustainable urban development was not mandatory under the Cohesion Policy 2007–13. As mentioned, the IU was launched in the framework of Article 8 of the ERDF regulation. This fact assured the impact of the urban dimension of the Cohesion Policy in the country, while in many other MS it lost visibility and contributed to improving cities mainly through sectoral approaches and instruments. On the contrary, the IU was able to enhance the importance of addressing the problems of urban decline in Spanish cities using URBAN as a reference. It was done by launching 46 programmes of urban regeneration with a territorial distribution that involved all the regions. All this identifies the importance of the inclusion of Article 8 in the ERDF regulation in the period 2007–13 of the Cohesion Policy, and also the importance of the decision taken by the Spanish government to use it. Adopting a temporal perspective, it is possible to observe that the mentioned decision has been crucial to advance towards a more ambitious scenario in the period 2014–20. In fact, in the current context, the experience of the IU has provided crucial knowledge in which to launch and define the ISUDS/EDUSI approach (under which 173 programmes are currently being developed). As a result, it can be considered that at the national level the IU has played an essential role in implementing the urban vision advised by the EC within the ‘urban mainstreaming’ approach (2007–13), and in allowing a smooth transition from URBAN to the ISUDS vision in the period 2014–20. The fact that similar instruments were not launched in most of the MS underlines the weakness of the EU policy in fields in which the decision on the implementation of the instruments available depends upon the priorities and interest of the MS.

Regarding the analysis of the programmes, it reveals that the IU has made little progress if compared with the URBAN II Community Initiative, as municipalities met difficulties in designing urban regeneration strategies according to the URBAN method. The following have been found:

Most cities had problems in integrating its strategy with the regional policy priorities and, generally, regions and provinces were not involved in the process of design of the strategy of urban regeneration.

Cities were successful in creating stable mechanisms for the coordination of the programmes, giving place to management practices aimed to facilitate the collaboration among different municipal areas involved in the implementation of the specific measures.

Cities were able of integrating into their programmes measures that tackled the social, physical and economic dimensions of urban decline. In a relevant number of cases they introduced measures aimed at introducing an environmental aspect (by addressing the energy and water consumption, and urban mobility).

Only some proposals were constructed on the basis of real participation, and few devised from the beginning a strategy to allow the development of a sustained process of dialogue and agreement between all the relevant stakeholders in the context of the implementation and monitoring of the programmes. In fact, few described the structures and rules for real participation and allocated funds for this.

In general, the proposals selected for the IU were not successful in presenting clear and consistent ideas on how their programmes were addressing innovation. Most identified the innovative dimension of their strategies with the adoption of the integrated and participative approach, but in many cases the review of the proposals reveals that it was only done to develop a discourse in line with the call.

The reality observed suggests that Spanish cities are still facing limitations when designing urban regeneration strategies that put into place the URBAN method, revealing at the same time that they are progressing in the integration of some of them. Mainly they show good results in the field of interdepartmental governance. The outcomes of the study demonstrate the relevance of the role played by the IU, even regarding the issues in which the programmes did not show a significant advance if compared with URBAN II. This is because the IU’s calls led cities to reflect on how to develop integrated regeneration strategies for their vulnerable areas. As a result, it has contributed to the continued developing of in-house knowledge at the local level.

This study shows that the most critical limitations of the IU have to do with those aspects less developed by cities under the URBAN and URBAN II Community Initiatives. This can be explained because the design of the IU was not based on an evaluation of those initiatives and because the Spanish scenario is characterized by significant inertias associated with the introduction of the integrated and participative approaches in urban policies. Regarding this, it would have been important to adapt the definition of the IU to the specific necessities and problems of the Spanish scenario, also taking into account regional and local characteristics (e.g., it would have been relevant to introduce a mechanism aimed to improve regional–local collaboration). This lesson can also be relevant in the context of other MS, showing the necessity to adapt EU instruments to the specific national and regional scenarios where they operate, transposing them on the basis of accurate analysis and diagnosis. It is something relevant to be taken into account in the current framework of negotiations for the definition of the urban dimension of the Cohesion Policy post-2020.

ORCID

Sonia De Gregorio Hurtado http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4654-5386

Notes

1. ‘The success of the URBAN Community Initiative is in no small measure due to the integrated approach. URBAN has targeted social and economic cohesion removing barriers to employability and investment at the same time as promoting social and environmental goals. The mobilization of a broad range of partners with different skills has underpinned this approach’ (European Commission, Citation2006, p. 12).

2. ‘Two generations of URBAN Community Initiative programmes have demonstrated the value of this integrated approach in around 200 cities across Europe’ (European Commission, Citation2009a, p. 5).

3. In this document, the European Parliament ‘highlights the positive experience of the URBAN Community Initiative concerning partnership, the integrated approach and the bottom-up principle … ’ (European Parliament, Citation2009, p. 7).

4. ‘Almost all of the case and comparative studies on the European Community Initiative URBAN as being evaluated for this investigation confirm an enormous effect of the programme’. The study mentioned analyzed the URBAN Community Initiative through the contributions of the Academia, reviewing the relevant literature in English, French and German available in 2005.

5. ‘The ten years experiences within the Community Initiative URBAN I and II has demonstrated all over Europe that the successfully tested integrated, cross-sector and participative urban development approach contributes effectively to stabilize distressed urban neigbourhoods’ (Urban Future, Citation2005, p. 1).

6. The Urban Acquis, also called Acquis Urbaine, is the set of common principles that guides sustainable urban development in the EU. The document Promoting Sustainable Development in Europe. Achievements and Opportunities (European Commission, Citation2009) recognizes that the Urban Acquis ‘builds on the experience gained while supporting integrated and sustainable urban development’ in the EU and mentions that it is based on: ‘(i) The integrated and cross-sector approach of the URBAN Community Initiatives; (ii) The new instruments of urban governance, administration and management … successfully tested by the URBAN Community Initiatives; (iii) A targeted selection of towns, cities and eligible areas and the concentration of funding; (iv) Networking, benchmarking and the exchange of knowledge and know-how, building on the positive experience and results of the URBACT I Programme (p. 25).

7. In Spain this has been expressed by the Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda (Citation2007a, Citation2007b).

8. The Convergence Objective of the Cohesion Policy for the period 2007–13 was aimed to stimulate growth and employment in the least developed regions (threshold: gross domestic product (GDP) per capita of less than 75% of the EU-25 average) (European Commission, Citation2007).

9. The Regional Competitiveness and Employment Objective covered all the areas of the EU not eligible under the Convergence Objective. It aimed to reinforce regions’ competitiveness and attractiveness as well as employment by anticipating economic and social changes (European Commission, Citation2007).

10. They were the plenary meetings of the Red de Iniciativas Urbanas (Urban Initiatives Network), the arena in which the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios is informed yearly about the advancement of the IU. The plenary meetings attended took place on: 17 January 2012, 22 February 2013, 15 July 2014, 6 October 2015 and 3-4 November 2016 in Madrid. The author also attended the meetings in which the Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios presented the call and the results of the different selection processes of the ISUDS/EDUSI programmes. The first of these took place jointly with the meeting of the plenary of the Red the Iniciativas Urbanas of 3-04 November 2016; the second took place on the 16 October 2017.

11. This was the managing authority of the IU.

12. Translation by the author from the original in Spanish.

13. Translation by the author from the original in Spanish.

14. In any case, the observation of the territorial distribution of the URBAN and URBAN II programmes showed that the managing authority (Dirección General de Fondos Comunitarios of the Ministry of Finance) tried to achieve a geographical balance (De Gregorio, 2012).

15. Albacete, Alcalá de Guadaira, Alicante, Almería, Arona, Barcelona, Burgos, Cádiz, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Ceuta, Córdoba, A Coruña, Coslada, Cuenca, Ferrol, Gandia, Getafe, Hospitalet de Llobregat, Huesca, Jaén, Jerez de la Frontera, Leganés, Linares, Logroño, Lorca, Lugo, Madrid, Málaga, Melilla, Mérida, Motril, Murcia, Oviedo, Palencia, Palma de Mallorca, Pamplona, Santa Coloma de Gramenet, Santa Lucía de Tirajana, Santiago de Compostela, Sevilla, Talavera de la Reina, Torrelavega, Torrent, Vitoria and Vélez-Málaga.

16. The Operational Programmes are documents approved by the European Commission for the implementation of a Community Support Framework. They comprise a set of multiannual priorities funded by one or more funds.

17. Mentioned in the programmes as Consejos de barrio, Comisiones Vecinales or Consejo de Participación del Distrito.

REFERENCES

- Atkinson, R. (2007). EU urban policy, European urban policies and the neighbourhood: An overview of concepts, programmes and strategies. Paper presented at the EURA Conference ‘The Vital City’, Glasgow, June 12–14, 2007.

- Atkinson, R. (2014). The urban dimension in Cohesion Policy: Past developments and future prospects. Paper presented at RSA workshop on ‘The New Cycle of the Cohesion Policy in 2014–2020’, Institute for European Studies, Vrije Universitetit Brussels, March 24, 2014.

- Carpenter, J. (2011). Integrated urban regeneration and sustainability: Approaches from the European Union. In A. Colantonio & T. Dixon (Eds.), Urban regeneration and social sustainability: Best practice from European cities (pp. 83–101). Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Carpenter, J. (2013). Sustainable urban regeneration within the European Union. A case of ‘Europeanization’? In E. M. Leary & J. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge companion to urban regeneration (pp. 138–147). London: Routledge.

- Cheshire, P. C., & European Commission. (1988). Urban Problems and Regional Policy in the European Community. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2009). El desarrollo de las Iniciativas Comunitarias URBAN y URBAN II en las periferias degradadas de las ciudades españolas. Una contribución a la práctica de la regeneración urbana en España. Ciudades, 13, 39–59.

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2012a). Políticas urbanas de la Unión Europea desde la perspectiva de la Planificación Colaborativa. Las Iniciativas Comunitarias URBAN y URBAN II en España (PhD Thesis). Departamento de Urbanística y Ordenación del Territorio, Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2012b). La regeneración urbana en la acción estatal en España durante el periodo 2004–2011. Una historia a continuar. Perspectivas, 1, 27–51.

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2017a). Is EU urban policy transforming urban regeneration in Spain? Answers from an analysis of the Iniciativa Urbana (2007–2013). Cities, 60(A), 402–414. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.015

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S. (2017b). A critical approach to EU urban policy from the viewpoint of gender. Journal of Research on Gender Studies, 7(2), 200–217.

- De Gregorio Hurtado, S., & González Medina, M. (2017). Las EDUSI en el contexto de las políticas de regeneración urbana en España. RI-SHUR, 6(2), 54–80.

- De Santiago, E. (2017). Il processo di sviluppo dell’agenda urbana dell’UE: dalla dichiarazione di Toledo al patto di Amsterdam, in TRIA, 18, 23-46..

- Dukes, T. (2008). The URBAN programme and the European urban policy discourse: Successful instruments to Europeanize the urban level? GeoJournal, 72(1–2), 105–119. doi: 10.1007/s10708-008-9168-2

- European Commission (EC). (1990). Green Paper on the urban environment. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- European Commission (EC). (2003). Partnership with the cities. The URBAN Community Initiative. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- European Commission (EC). (2006). Cohesion Policy and cities : The urban contribution to growth and jobs in the regions. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- European Commission (EC). (2007). Cohesion Policy 2007–2013. Commentaries and official texts.

- European Commission (EC). (2008a). Fostering the urban dimension. Analysis of the Operational Programmes co-financed by the European regional development fund (2007–2013). Brussels: Working Document of the Directorate-General for Regional Policy. Commission of the European Communities.

- European Commission (EC). (2008b). Commission staff working document: State aid control and regeneration of deprived urban areas. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- European Commission (EC). (2009). Promoting sustainable urban development in Europe. Achievements and opportunities. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

- European Council. (2006). Council decision of 6 October 2006 on Community strategic guidelines on cohesion (2006/702/EC). Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri = OJ:L:2006:291:0011:0032:EN:PDF

- European Parliament. (2009). Report on the urban dimension of Cohesion Policy in the new programming period (2008/2130(INI). Author.

- Frank, S., Holm, A., Kreinsen, H., & Birkholz, T. (2006). The European URBAN experience – Seen from the academic perspective. Study Report. Study project funded by the URBACT programme. Berlin: Humboldt Study Team.

- García Jaén, P. (1998). Aplicaciones de la Iniciativa Comunitaria URBAN. Boletín de la A.G.E, 26, 191–206.

- González Medina, M., & Fedeli, V. (2015). Exploring European Urban Policy: Towards an EU Urban Agenda? Gestión y análisis de políticas públicas (nueva época), 14, 8–22.

- Gutierrez Palomero, A. (2009). La Unió Europea i la regeneració de barris amb dificultats (PhD Thesis). Departament de Geografia i Sociologia, Universitat de Lleida.

- Gutierrez Palomero, A. (2010). La Iniciativa Comunitaria URBAN y la construcción inconclusa de una política urbana para la Unión Europea. Papeles de Geografía, 51–52, 159–167.

- Hall, P. (1987). Las ciudades de Europa: ¿un problema europeo?, ¿una profesión europea? Urbanismo, 1, 25–31.

- Huete, M. A., Merinero, R., & Muñoz, R. (2014). Políticas de regeneración urbana en España: Propuesta de análisis para su adecuación al Modelo Europeo de Desarrollo Urbano Integral. Metodología de Encuestas, 16, 45–66.

- Informal Meeting of Ministers on Urban Development of the EU. (2007). Leipzig charter. Leipzig. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/themes/urban/leipzig_charter.pdf

- Informal Meeting of Ministers on Urban Development of the EU. (2010). Toledo declaration. Retrieved from http://urban-intergroup.eu/wp-content/files_mf/es2010itoledodeclaration.pdf

- Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. (2007a). Marco Estratégico Nacional de Referencia 2007–2013. Madrid: Author.

- Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. (2007b). Iniciativa Urbana (URBAN). Orientaciones para la elaboración de propuestas. Madrid: Author.

- Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda. (undated). Note for the media. Retrieved from http://www.urbanpalencia.es/media/nota_prensa_urban.pdf

- Official Journal of the EU. (2006). Regulation EC 1080/2006, L210, p. 6.

- Parkinson, M. (1992). Urbanization and the function of cities in the European Community. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Parkinson, M. (2005). Urban policy in Europe: Where have we been and where are we going. In E. Antalowsky, J. S. Dangschat, & M. Parkinson (Eds.), European metropolitan governance: Cities in Europe – Europe in cities (pp. 7–32). Vienna: NODE research.

- Partido Socialista Obrero Español. (2004). Merecemos una España mejor. Programa electoral elecciones generales 2004. Madrid: Author.

- Rodriguez Álvarez, J. M. (2005). La Iniciativa Comunitaria europea URBAN y sus efectos en España. Paper presented in the VII Congreso Español de Ciencia Política y de la Administración. Democracia y Buen Gobierno, Madrid, September 21–23, 2005.

- Tortola, P. D. (2016). Europeanization in time: Assessing the legacy of URBAN in a mid-size Italian City. European Planning Studies, 24(1), 96–115. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2015.1062083

- Urban Future. (2005, June 8–9). ‘The Acquis Urban’. Using cities’ best practices for European Policy. Community Declaration on URBAN cities and players at the European Conference ‘Urban Future’, Saarbrucken, Germany. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/newsroom/document/pdf/saarbrucken_urban_en.pdf

- Van den Berg, L., Braun, E., & Van der Meer, J. (2007). National policy responses to urban challenges in Europe. Aldershot: Routledge.