ABSTRACT

This paper explores whether European Union (EU) regional spending influenced how local areas voted in the UK’s 2016 EU referendum. While much focus has been on identity and demographic factors in explaining the referendum result, little attention has been paid to the role of EU interventions in the UK’s regions. This paper provides an initial exploration into this by assessing the role of EU regional spending. It finds the level of EU spending in local areas had little impact on how those areas voted in the referendum, raising questions about the communication and awareness of EU regional spending.

INTRODUCTION

This paper contributes to the debate on whether European Union (EU) regional spending affects support for European integration. The UK’s vote to leave the EU in June 2016 (‘Brexit’) puts this question into sharp focus. Shortly after the referendum, European Commissioner for Regional Policy Corina Creţu expressed regret that areas supported by EU regional spending had nevertheless voted to leave:

The European Union stood by Wales when Wales decided to close down the mines. It was only thanks to European funds that … we were able to build new jobs, new economic activities. And of course it’s disappointing to see [the referendum result]. Of course we respect the British vote, but it was a big mistake for our part, our failure to explain that this region developed also due to European funds.Footnote1

Existing analyses on the referendum result have focused on the role of public opinion, social attitudes and values, and demographic factors (Clarke, Goodwin, & Whiteley, Citation2017; Curtice, Citation2017; Goodwin & Heath, Citation2016; Hobolt, Citation2016), as well as drawing on long-standing debates surrounding Britain’s relationship with the EU (Evans & Menon, Citation2017). Place-based analyses have also tried to unpick the geography of the vote, for example, focusing on the local economic impact of Brexit (Dhingra, Machin, & Overman, Citation2017).

There has already been some discussion on post-Brexit Cohesion Policy and regional funding (e.g., Bachtler & Begg, Citation2017; Bell, Citation2017; Di Cataldo, Citation2017; Huggins, Citation2018; Sykes & Schulze Bäing, Citation2017). However, analysis into the role of EU regional spending in influencing the referendum outcome is lacking. Exploring this is important for three reasons. First, it addresses a gap in current understanding of the referendum outcome. While much focus has been on individual socio-demographic factors and the nature of the debate UK-wide, little attention has been paid to the role of EU regional spending. Second, it complements ongoing debates about the role of EU regional spending to foster support for European integration (e.g., Chalmers & Dellmuth, Citation2015; Dellmuth & Chalmers, Citation2018; Mendez & Bachtler, Citation2016), and even a sense of European identity (Capello, Citation2018; Capello & Perucca, Citation2018). This is especially relevant given one of the stated aims of EU regional policy is to develop social cohesion. It is claimed this fosters a sense of solidarity among EU citizens and, by extension, EU support and a sense of European identity (Bachtler, Mendez, & Wishlade, Citation2013, p. 12; Capello & Perucca, Citation2018, p. 1452). Third, it has policy relevance. Cohesion Policy accounts for one-third of the EU’s budget but, in light of post-2020 proposals, it is coming under increased scrutiny from scholars and policy-makers about its effectiveness (e.g., Fratesi & Wishlade, Citation2017).

This paper therefore opens this field of enquiry by presenting an initial exploration into the following research question: What impact, if any, did the level of EU regional spending have on how local areas voted in the EU referendum? This is achieved through an aggregate-level analysis of EU regional spending and the referendum outcome at the NUTS-3 level.Footnote2 Overall, the paper finds that the level of EU spending in local areas had little impact on how those areas voted in the referendum. These results pose significant questions for how EU regional spending is communicated to and received by citizens.

EU REGIONAL SPENDING, EU SUPPORT AND BREXIT

The existing literature on support for the EU debates whether that support is driven by economic or identity factors (e.g., Hooghe & Marks, Citation2005). This essentially comes down to whether EU support is rationally driven, for example, through cost–benefit analyses or driven by social identity.

The relationship between EU regional spending and EU support is central to this debate. EU regional spending and its role in encouraging social cohesion is believed to foster solidarity among EU citizens and, in turn, increase support for European integration (Bachtler et al., Citation2013, p. 12; Capello & Perucca, Citation2018, p. 1452). Following the rationalist approach, then, it is posited that greater spending in regions by the EU will make those living in those regions more supportive of the EU. Early research has indeed found a positive relationship between the level of regional spending and the support for the EU, but that support was conditional upon an awareness of EU regional funds being spent in the first place (Osterloh, Citation2008).

Indeed, recent research highlights a more complicated picture, finding that the role of regional spending in fostering EU support is often mediated by social identity and socio-demographic factors, such as education. For example, Chalmers and Dellmuth (Citation2015) find that the role of EU regional spending to foster EU support is stronger among those holding a European communal identity and those who are more politically aware. The perceived fit of EU regional spending to local economic need is also shown to be important; EU regional spending is more positively received in areas where it addresses local economic need (Dellmuth & Chalmers, Citation2018). In this way, support for the EU is not simply down to receiving higher levels of investment and may often depend on factors that are outside the EU’s control.

Existing analysis of the EU referendum result has so far found social identity and demographic factors played a crucial role. In particular, areas with higher percentages of younger people and university graduates were more likely to vote ‘remain’ (Goodwin & Heath, Citation2016). This is confirmed in individual-level analyses (Curtice, Citation2017). In a broader context, it has been argued that the leave vote was strongest in areas that have been socially and economically ‘left behind’ (e.g., Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the impact of direct EU interventions, such as EU regional spending, is relatively unexplored.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND DATA

A data set was compiled using EU referendum results at the local authority level, provided by the Electoral Commission, and 2007–13 EU regional spending as at 2014, provided by the European Commission. Expenditures, rather than allocations, were used on the presumption that citizens would only be aware of EU regional spending that is actually spent. EU regional spending was operationalized into a per capita variable using 2014 population estimates from the Office of National Statistics (ONS). The addition of demographic data from the 2011 census, also from the ONS, allows for control variables to be included later on in the analysis. Specifically: percentage of the population under 45 years, percentage of the population with undergraduate degrees and above, and a dummy variable for regions in Scotland and Northern Ireland. For a full list of variables used in this analysis, see the supplemental data online.

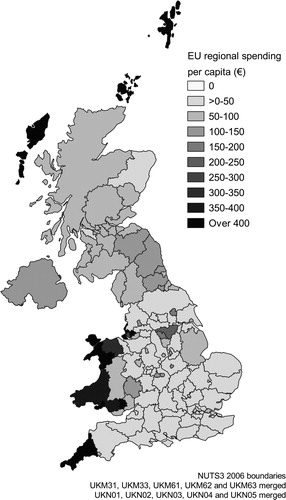

All data were aggregated at NUTS-2 and NUTS-3 levels. This was done using 2006 boundaries as this was the basis for the EU regional expenditures data. This analysis focuses primarily on the NUTS-3 level (). While NUTS-1 and NUTS-2 boundaries represented the functional geography of EU regional policy during 2007–13, these regions are also spatially large, meaning citizens based in one part of a region may not be readily exposed to EU regional spending in another part. Furthermore, the level of EU regional spending can vary substantially within NUTS-2 regions.Footnote3 Focusing on the more granular NUTS-3 regions mitigates this, as it provides a lower level of analysis where EU spending in local areas is more likely to be recognized by citizens living in those areas.

The data set covers all the UK. However, owing to some local authority boundaries in Scotland not conforming to NUTS boundaries, some regions here have been merged.Footnote4 Furthermore, Northern Ireland reported the referendum result as a single entity and so data here are only available at the NUTS-2 level.Footnote5 Gibraltar was excluded from the analysis as there is no readily available data on EU regional spending in this region.

RESULTS

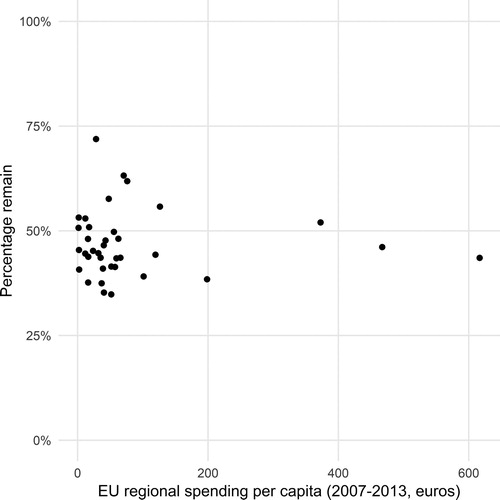

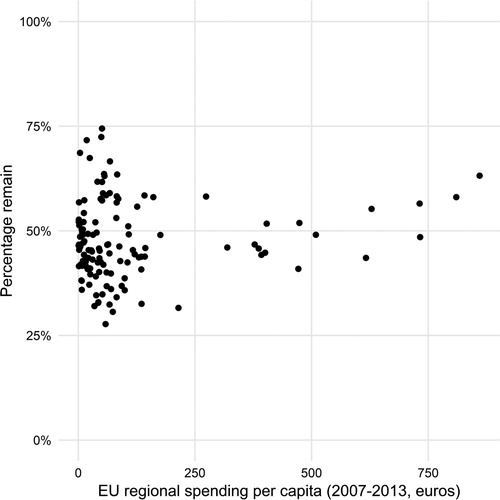

and display the relationship between per capita EU regional spending and support for ‘remain’ at the NUTS-2 and NUTS-3 levels respectively. Both scatterplots do not obviously support the presence of a relationship between the two variables. This is confirmed by Spearman correlations, showing insignificant and weak associations between EU regional spending and support for remain at the both the NUTS-2 (rs = −0.051, p = 0.77) and NUTS-3 (rs = 0.043, p = 0.63) levels.Footnote6

Figure 2. European Union regional spending (2007–13) and remain votes in NUTS-2 regions (2006 boundaries).

Figure 3. European Union regional spending (2007–13) and remain votes in NUTS-3 regions (2006 boundaries).

As noted, existing research on the referendum outcome shows support for remain was greater in areas with higher proportions of younger voters and with higher proportions of those educated to degree level and above (e.g., Goodwin & Heath, Citation2016). There was also an inherent territorial dimension to the referendum result, with Scotland and Northern Ireland in particular leaning for remain. This serves as the basis of a two-step hierarchical regression, using the percentage aged under 45 years, the percentage of university graduates and a Scotland/Northern Ireland dummy variable as control variables (). Step 1 models the effect of the control variables alone. In line with existing research on the referendum, this accounts for a substantial amount of the variation in the level of the remain vote (R2 = 0.808). Step 2 introduces EU regional spending. This variable has an extremely small, but nevertheless significant, effect on the level of support for remain. While this does account for more variance (R2 = 0.835), its overall impact is minimal.Footnote7

Table 1. Two-step hierarchical regression for variables predicting percentage remain at the NUTS-3 level.

DISCUSSION

Overall, this analysis finds little evidence of a strong relationship between the level of per capita EU regional spending and the percentage voting ‘remain’ at the NUTS-3 level. This indicates that, at best, the role of EU regional spending in the outcome of the UK’s 2016 EU referendum was minimal. This finding raises questions for future analysis both on the impact of EU regional spending in the context of the Brexit vote and for the wider role of EU regional spending to foster EU support.

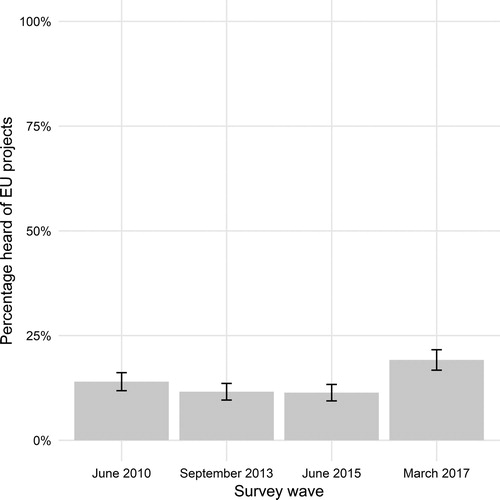

The first of these questions centres on communication and awareness. As noted, existing research highlights that the ability of EU spending to affect EU support is often conditional upon citizens being aware of the spending in the first place (Osterloh, Citation2008). Awareness of EU regional spending (as measured in the Flash Eurobarometer surveys on EU regional policy) has been consistently low in the UK (< 15% before the referendum). While awareness saw a sharp increase after the EU referendum, it nevertheless remains the case that only a minority (< 20%) are aware of EU regional spending in their local areas ().

This question of communication has become increasing important. This is partly a response to Brexit, but also reflects the context of the post-2020 EU budget, where the effectiveness Cohesion Policy is increasingly scrutinized by scholars and policy-makers (e.g., Fratesi & Wishlade, Citation2017). However, the issue of communication goes beyond raising awareness of EU regional spending among citizens. Focus group research of Welsh ‘leave’ voters, for example, shows that despite being aware of EU-funded projects in their local area, many regarded them as ‘vanity projects’ with little worthwhile impact on the local community (Awan-Scully, Citation2017). Similar attitudes were identified in North East England, and recent research has highlighted how citizens across the EU want more input into how EU funds are spent (Pegan, Mendez, & Triga, Citation2018).

A second question, related to communication and awareness, centres on how well ‘embedded’ EU regional spending has been in the UK. This is especially the case in England, where, following the abolition of regional development agencies in 2010, the subnational institutional landscape has been in a state of flux, preventing a long-term and coherent approach to EU regional policy being developed (Bachtler & Begg, Citation2017). The management of EU regional spending has also become centralized. Although responsibility for setting local priorities for the 2014–20 programme was devolved to local enterprise partnerships (LEPs), a lack of capacity and limited room for manoeuvre effectively limited LEPs’ ability to shape EU regional spending strategies to suit their areas (Huggins, Citation2014). Given existing research showing the fit between EU regional spending and local economic need is important (Dellmuth & Chalmers, Citation2018), local input and control is crucial and increasingly demanded by citizens (Pegan et al., Citation2018).

Overall, then, while this analysis finds the raw level of EU regional spending played a very limited role in influencing the referendum result, it opens up further questions and highlights the need to engage in further research on its role in fostering EU support, both in the context of Brexit and beyond.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper sought to provide an initial exploration into the impact of EU regional spending on influencing the UK’s referendum. Overall, the analysis found the level of EU regional spending in local areas had little impact on how those areas voted in the referendum.

There are, of course, caveats to this analysis. It has only analyzed aggregate-level data, and NUTS-3 regions are still relatively large. As such, future research should focus on individual-level analysis. Furthermore, referendums only offer sporadic tests of public opinion, which are often dominated by domestic political issues (Osterloh, Citation2008). This was arguably the case with the UK’s EU referendum. The UK’s position as a net contributor to the EU did feature in the campaign, but this was in the context of how payments currently made to the EU could be spent on national priorities, such as the National Health Service (NHS). Overall, however, the campaign was dominated by discourse on the impact of the EU on the UK’s economy for the remain side, and on immigration and sovereignty for the leave side (Clarke et al., Citation2017; Evans & Menon, Citation2017); the role of EU regional spending barely featured. These limitations aside, however, as an initial exploration into the role of EU regional spending in the referendum outcome, this paper makes two contributions that guide further research and highlight the importance of these results beyond the UK’s context.

First, the finding that EU regional spending had little impact on the referendum result speaks to wider research on the role of EU regional spending to foster EU support and identity (e.g., Capello & Perucca, Citation2018; Chalmers & Dellmuth, Citation2015; Dellmuth & Chalmers, Citation2018), which shows a range of other factors play a mediating role. A lack of awareness of EU regional spending is one potential explanation, but this nevertheless highlights the need for future research to look beyond the mere level of spending.

Second, in a context where EU Cohesion Policy is coming under increased scrutiny for its effectiveness and communication, the findings also have policy implications. The EU has spent significant sums in UK regions, but this did not directly translate into EU support. This raises significant questions about the efficacy of EU regional spending to foster EU support, and how EU regional policy is perceived, particularly during high-profile debates on EU membership. Indeed, much analysis since the referendum outcome has focused on how areas voting to leave have been economically and socially ‘left behind’ (e.g., Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). Cohesion Policy is supposed to address these imbalances, but in the case of the UK’s Brexit vote, it only had an extremely limited impact on how local areas voted.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.1 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the Regional Studies Association for waiving the article processing charge for this article, as well as the editorial team and reviewers for their guidance and feedback on earlier drafts.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Christopher Huggins http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0108-7887

Notes

1 Remarks delivered during the opening session of the 2016 European Week of Regions and Cities (http://cor.europa.eu/Pages/EWRC-2016-webstreaming.html).

2 NUTS = Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics.

3 This variation in EU spending is indicated in the supplemental data online and accounts for differences in the means, maximums and minimums observed between the NUTS-2 and NUTS-3 data.

4 At the NUTS-2 level, UKM3 and UKM6 were merged. At the NUTS-3 level, UKM31, UKM33, UKM61, UKM62 and UKM63 were merged.

5 Northern Ireland data exist at the parliamentary constituency level, but they do not conform to the NUTS-3 boundaries.

6 Spearman correlations were used as the EU regional spending data are highly positively skewed. While the coefficients are small, they indicate a difference in directionality, with the NUTS-2 correlation being negative and NUTS-3 correlation being positive. However, applying 95% confidence intervals shows both coefficients cross zero (NUTS-2 [−0.373, 0.282]; NUTS-3 [−0.133, 0.217]).

7 Given its high positive skew, these models were also run with a log of the EU regional spending per capita variable. For the results of this, see the supplemental data online, but it confirms the results presented in , where the effect of EU regional spending is extremely small.

REFERENCES

- Awan-Scully, R. (2017). New research shows deep divisions persisting on Brexit. Retrieved from: https://blogs.cardiff.ac.uk/brexit/2017/10/26/new-research-shows-deep-divisions-persisting-on-brexit/.

- Bachtler, J., & Begg, I. (2017). Cohesion policy after Brexit: The economic, social and institutional challenges. Journal of Social Policy, 46(4), 745–763. doi: 10.1017/S0047279417000514

- Bachtler, J., Mendez, C., & Wishlade, F. (2013). EU cohesion policy and European integration: The dynamics of EU budget and regional policy reform. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Bell, D. N. F. (2017). Regional aid policies after Brexit. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 33(S1), S91–S104. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/grx019

- Capello, R. (2018). Cohesion policies and the creation of a European identity: The role of territorial identity. Journal of Common Market Studies, 56(3), 489–503. doi: 10.1111/jcms.12611

- Capello, R., & Perucca, G. (2018). Understanding citizen perception of European Union cohesion policy: The role of the local context. Regional Studies, 52(11), 1451–1463. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1397273

- Chalmers, A. W., & Dellmuth, L. M. (2015). Fiscal redistribution and public support for European integration. European Union Politics, 16(3), 386–407. doi: 10.1177/1465116515581201

- Clarke, H. D., Goodwin, M., & Whiteley, P. (2017). Brexit: Why Britain voted to leave the European Union. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curtice, J. (2017). Why leave Won the UK’s EU referendum. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(S1), 19–37.

- Dellmuth, L. M., & Chalmers, A. W. (2018). All spending is not equal: European Union public spending, policy feedback and citizens’ support for the EU. European Journal of Political Research, 57(1), 3–23. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12215

- Dhingra, S., Machin, S., & Overman, H. G. (2017). The local economic effects of Brexit (CEP Brexit Analysis No. 10). London: Centre for Economic Performance.

- Di Cataldo, M. (2017). The impact of EU objective 1 funds on regional development: Evidence from the U.K. and the prospect of Brexit. Journal of Regional Science, 57(5), 814–839. doi: 10.1111/jors.12337

- Evans, G., & Menon, A. (2017). Brexit and British politics. Cambridge: Polity.

- Fratesi, U., & Wishlade, F. G. (2017). The impact of European cohesion policy in different contexts. Regional Studies, 51(6), 817–821. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2017.1326673

- Goodwin, M. J., & Heath, O. (2016). The 2016 referendum, Brexit and the left behind: An aggregate-level analysis of the result. Political Quarterly, 87(3), 323–332. doi: 10.1111/1467-923X.12285

- Hobolt, S. B. (2016). The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. Journal of European Public Policy, 23(9), 1259–1277. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2016.1225785

- Hooghe, L., & Marks, G. (2005). Calculation, community and cues. Public opinion on European integration. European Union Politics, 6(4), 419–443. doi: 10.1177/1465116505057816

- Huggins, C. (2014). Local enterprise partnerships and the development of European structural and investment fund strategies in England. European Structural and Investment Funds Journal, 2(2), 183–189.

- Huggins, C. (2018). The future of cohesion policy in England: Local government responses to Brexit and the future of regional funding. Cuadernos Europeos de Deusto, 58, 131–153. doi: 10.18543/ced-58-2018pp131-153

- Mendez, C., & Bachtler, J. (2016). European identity and citizen attitudes to cohesion policy: What do we know? (Cohesify Research Paper 1). Glasgow: European Policies Research Centre.

- Osterloh, S. (2008). Can regional transfers buy public support? Evidence from EU structural Policy (ZEW Discussion Paper No. 11-011). Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung.

- Pegan, A., Mendez, C., & Triga, V. (2018). What do Citizens Think of Cohesion Policy and Does it Matter for European Identity? A Comparative Focus Group Analysis (Cohesify Research Paper 13). Glasgow: European Policies Research Centre.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Sykes, O., & Schulze Bäing, A. (2017). Regional and territorial development policy after the 2016 EU referendum – initial reflections and some tentative scenarios. Local Economy, 32(3), 240–256. doi: 10.1177/0269094217706456