ABSTRACT

With growing pressure to contribute to their region's development, universities are increasingly called upon to engage dynamically in innovation policy-making and governance activities. Previous studies suggest in their collaboration with local and regional government that universities can emerge as animateurs, providing guidance, consolidating networks, and ultimately activating institutional and human agency. This is especially important in the context of less-developed regions, where the unlocking of innovative potential may rest on those factors. This paper provides an extended perspective on universities’ engagement in innovation policy processes and, in a broader sense, on the collaboration between these higher education institutions and local and regional government. Through an analysis of the partnership between two Portuguese institutions, the University of Aveiro and the intermunicipal community of the region of Aveiro, this study explores the potential implications on regional innovation policy and the activation of institutional agency in a less-developed context. Policy documents, reports and interview data from 18 academics, top managers, policy-makers and other stakeholders show that while institutional expectations differ, collaborative interplays have boosted the formation and growing effectiveness of regional innovation networks, crucial for the development of less-developed regions.

INTRODUCTION

Higher education institutions (HEIs) are considered key drivers of regional economic development (Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000). With regions progressively dependent on knowledge-intensive activities to compete globally (Arbo & Benneworth, Citation2007), universities can leverage development gaps as local ‘anchors’ of wider economic activity (Goddard, Coombes, Kempton, & Vallance, Citation2014). As a result, the third academic mission of regional engagement emerged as the institutionalization of this capability and (expected) responsibility of universities toward the socioeconomic development of their regions (Etzkowitz, Citation1990; Gunasekara, Citation2006a).

Accordingly, HEIs and scientific knowledge are commonly acknowledged by firms and government authorities as an advantage in the search for innovation, economic growth and social development (Arbo & Benneworth, Citation2007; Uyarra, Citation2010). However, while increasingly the case in more developed, high-tech regions (Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013), this linkage between science and other institutional spheres is not straightforward in less-developed regions (LDRs). To activate innovation dynamics, they need to circumvent a circumstantially ‘weak’ and fragmented environment, of insufficient research and development (R&D) activity and lack of interaction between regional agents (Rodrigues, da Rosa Pires, & de Castro, Citation2001). The question is if in this they stand to gain from the knowledge resources provided by a university.

According to Drucker and Goldstein (Citation2007), in the wake of a knowledge-based economy, strategies have been designed by state agencies to leverage the impact of universities in the region. Nonetheless, although such projects have advanced the translation of university knowledge resources into economically viable outputs (Pugh, Hamilton, Jack, & Gibbons, Citation2016), they may have failed to grasp the full potential of universities’ agency. Conceptualizations of regional development and innovation systems often contemplate the triptych of university, industry and state (e.g., the Triple Helix Model), or even these in combination with a growing number of spheres (e.g., Mode 3). However, university–industry collaboration and research commercialization are usually the focus in the study of these linkages, overshadowing potential benefits and widespread implications of universities’ engagement with local and regional government and their growing importance in policy design.

Albeit a less studied facet of their regional mission, universities’ engagement in governance activities has been increasingly embedded in policy agendas – at least on a supranational, discursive level. The current European Union (EU) Cohesion framework of smart specialization (Foray, David, & Hall, Citation2009) considers universities as more than key players, guides in regional innovation strategies’ formulation and implementation processes. On a conceptual level, universities’ regional governance activities is under-researched. The few existent examples include Gunasekara (Citation2006b), Aranguren, Larrea, and Wilson (Citation2009), Rodrigues and Melo (Citation2013) and Pugh et al. (Citation2016). Though predominantly small-scale studies of short-lived events, these highlight the potential of a mutually beneficial relationship between universities and regional government, in building knowledge infrastructures, learning dynamics and institutional capacity. The above-mentioned authors defend the notion that universities can assume a leading role in this type of engagement, successfully promoting associative or networked governance and more rational and efficient decision-making and planning. It is important, therefore, to analyze latent qualities in this relationship, and to consider whether these initiatives have the capacity to mature and lead to more long-term institutional commitments.

This paper explores the nature of universities–regional government collaboration in the design of territorial development strategies in an LDR. It seeks to answer the following questions:

Why and how do universities and regional government authorities start collaborating in matters of innovation and regional development policy design?

What are the main challenges in this type of collaboration during the strategy-building process?

In what way does the participation of the university shape innovation policy-making and institutional capacity in LDRs?

The paper is structured as follows. The literature review is structured inversely: it establishes the main challenges in unlocking innovation potential in an LDR, followed by an illustration of how universities’ engagement in governance and policy design can help overcome them. The next section discusses how universities’ incorporation in the policy process has been framed in both discourse and practice, and the main motivations and challenges in this linkage. A case study approach provides an in-depth perspective into the process and institutional dynamics involved, peering into the potential impact of a university in institutional capacity-building, regional governance and development. Consequently, the partnership formed between the University of Aveiro (UA) and the Intermunicipal Community of the Region of Aveiro (CIRA), two relevant institutions located in the LDR of Centro, in Portugal, is pertinent to explore this. It adds to previous literature (Aranguren et al., Citation2009; Gunasekara, Citation2006b; Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013) by providing an extended in-depth perspective of this link. Two policy periods are analyzed, approaching opportunities, challenges and the potential implications of institutional collaboration. Documents and thematic analysis of interviews with academics, policy-makers and other regional stakeholders are used. Findings suggest while institutional expectations conflict, collaboration has boosted the formation and growing effectiveness of regional innovation capacity, especially needed in the context of this LDR.

ACTIVATING INNOVATION IN LDRs: WHY UNIVERSITIES AND INSTITUTIONAL COLLABORATION MATTER

Universities’ role in fomenting regional innovation has been widely emphasized (Arbo & Benneworth, Citation2007; Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000). However, while more developed regions with strong innovation systems generally succeed in translating knowledge into the productive sector, LDRs struggle at establishing this connection (Bonaccorsi, Citation2016; Huggins & Johnston, Citation2009; Rodrigues et al., Citation2001). Typical shortcomings of LDRs in promoting innovation-based development include insufficient and inefficient locally based R&D activities, paired with a low demand for innovation from local firms; and institutional fragmentation with lack of interaction between economic and institutional agents (Huggins & Johnston, Citation2009; Rodrigues et al., Citation2001). Thus, to foster innovation, LDRs should not just build up infrastructural and fundamentally quantitative and economic factors, but equally consider the institutional, cultural and inherently social dimensions supporting it.

The latter may be the crucial factor to tackle in LDRs, as the skill to engage in collaborative action must be honed to deliver successful regional projects (Morgan & Henderson, Citation2002). This echoes Hirschman’s (Citation1958, p. 25) argument that the great problem in unbalanced development is a ‘basic deficiency in organization’ and a lack of energetic human agency. This suggests activating individual or shared leadership potentially improves institutional effectiveness (Beer & Clower, Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). Ultimately, difficulty implementing a coordinated and determined action amounts to not a lack of resources, but an inability in effectively gathering and using them – to deficient communication skills and a failure ‘to explore joint solutions to common problems’ (Morgan & Nauwelaers, Citation1999, p. 3). Therefore, successfully interconnecting and capturing institutional actors’ willingness and capacity to exchange resources, of a scientific or practical base, should be considered for more viable development policies and regional innovation.

An important actor capable of activating these collaborative practices and innovation dynamics is the university. By supporting a knowledge infrastructure, regionally engaged universities particularly can stimulate regional networking and institutional capacity-building (Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000; Pugh et al., Citation2016). Oft overlooked, their engagement in governance and policy design is an important mean to accomplish this. Universities are uniquely capable of providing resources, analysis, leadership and credibility in regional development strategies and trajectories. Moreover, guided, in principle, by the search of objective truth and a sense of civic responsibility, universities can contribute to rational and informed policy-making and regional governance.

It is believed universities’ regional collaboration with policy-makers and engagement in governance activities can trigger effective and sustained learning processes (Aranguren et al., Citation2009; Gunasekara, Citation2006b). Furthermore, the general perception in stakeholder networks of universities as ‘honest brokers’ is an advantage in the power-governed policy sphere, promoting network and collaborative approaches based on mutual trust and enabling decentralized decision-making mechanisms (Gunasekara, Citation2006b, p. 729). Some studies on this developing link echo these findings, suggesting this collaboration can evolve towards co-generation of knowledge, enable more deliberative democratic processes and build institutional capacity (Rodrigues et al., Citation2001; Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013; Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017). Nevertheless, it is important to consider the policy sphere does not easily grant entry. And an encouraging milieu is needed to enable universities’ expansion of their engagement initiatives into governance (Gunasekara, Citation2006b).

From discourse to practice

With the academic literature on economic geography, regional development and innovation increasingly emphasizing the advantage regionally engaged universities can have, interest has also grown on the part of policy-makers. This is more evident on a discursive level, where development and political trends lead policy-makers to underline the importance of R&D investment, scientific and technological resources and HEIs. Allusions to academic concepts persist, such as the Triple Helix Model of university–industry–state collaboration (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000), and its four-helix extension with a public/consumer sphere (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009). There are examples of practical applications of these academic models (Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013), but the instances in which these were implemented with academic guidance might be relatively fewer. Ultimately, it is a distinction between an academic guiding concept for public policy and academic guidance itself. The latter has greater probability of grounding a policy to the local context, of activating endogenous resources, institutional and human agency, while bringing originality and inventiveness in doing so.

A current example that considers the strategic incorporation of universities in the policy process is the smart specialization concept (Foray et al., Citation2009). Intended as a tailored innovation policy to decrease regional disparities, its uniqueness relies on three aspects. First, it considers the collaborative character of innovation, delineating a process in which several regional stakeholders (e.g., universities, firms, entrepreneurs) discuss and progressively define areas of competence and growing trends for the region's development – the entrepreneurial process of discovery. Second, it highlights universities as central actors in strategy design, imbuing them with a heightened responsibility in planning and regional innovation. Finally, the European Commission (EC) defined it as an ex-ante conditionality for regions to access European Regional Development Funds (ERDF), implying its mandatory application. This meant a steep learning curve for most regions, but consequently interesting experiments of university–regional government collaboration have surface throughout Europe.

Nonetheless, it is evident that putting institutions with different expectations, organizational arrangements and culture working together is not a seamless process. Within universities, integrating the third mission into an institutional strategy and academic routine dictated by the first two is a convoluted process. Academic drivers are different for each mission, and engagement rarely factors into academic evaluation and career progression. This leads to research being detached from regional needs for international recognition (Bonaccorsi, Citation2016), and to only a limited few entrepreneurial, usually top-management staff externally collaborating (Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000). A technological push has also shaped universities’ engagement, often to the exclusion of more civic projects. Concomitantly, regional authorities’ ability to integrate these complex ‘loosely coupled’ HEIs into the process has not fully developed. Locally, HEI knowledge may face a lack of absorptive capacity (Bonaccorsi, Citation2016; Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000), and in itself, engagement with regional government can be challenging given administrative fragmentation, urban/rural divides and intra-regional competition. Ultimately, university and government authorities have their distinct missions and visions, accountability mechanisms and bureaucracy. To develop a partnership, traditions of engagement and institutional characteristics of the university system, along with the organization, autonomy, and multilevel obligations of the government authority, need to be considered. As per Aranguren et al. (Citation2009), this highlights the importance of the local context, policy environment and academic culture in shaping collaboration.

Once the link has been made, establishing university–regional government collaboration means balancing the inherent power in policy environments (Aranguren et al., Citation2009; Nicholds, Gibney, Mabey, & Hart, Citation2017). This is needed to avoid participation and control asymmetries, which can degenerate into tokenism, i.e., a symbolic inclusion of actors in the process, and/or autocratic or technocratic modes, the latter meaning here more prevalence of university actors. Balance can be achieved by managing conflicted interests and expectations, enabling dialogue and fostering shared leadership (Nicholds et al., Citation2017). Nurturing interactive collaborative modes can thus benefit these links, and ensure commitment of players involved in procedures and outcomes (Aranguren et al., Citation2009). Spurring collaboration, implies moving beyond consultancy, where university participation is ‘customer’-oriented, framed as a product, and follows traditional forms of communicating research results, toward an ‘action research’ approach (Aranguren et al., Citation2009), i.e., frequent interaction, co-design, participatory workshops and shared stakes. While this closeness may hamper actors’ neutrality, trust between partners can thus emerge, contributing to more informed, democratic and impactful policy processes.

Universities have increasingly been studied by their potential to activate innovation dynamics in a region, but their capacity to do so through their engagement with local and regional government in policy-making and regional strategies is under-researched. This literature review's purpose was to clarify universities’ potential in this area, particularly by stimulating regional networking and build institutional capacity. This is especially important in LDRs, where organizational and collaborative capabilities need to be nurtured more attentively. As universities are progressively invited to participate in regional innovation policy processes, the potential to help activate endogenous resources and institutional and human agency is there. Nevertheless, barriers and opportunities in universities’ collaboration with regional government authorities in policy design still need to be considered, so that such experiences have a greater chance of success. It is important to understand how these links can be forged, developed and strengthened, and why this matters in practice. This study thus explores this through UA–CIRA collaboration in the design of territorial development strategies in an LDR – the region of Aveiro, Portugal. It seeks to provide an in-depth perspective into the process and institutional dynamics involved, and the university's potential impact in institutional capacity-building, regional governance and development. The guiding questions are:

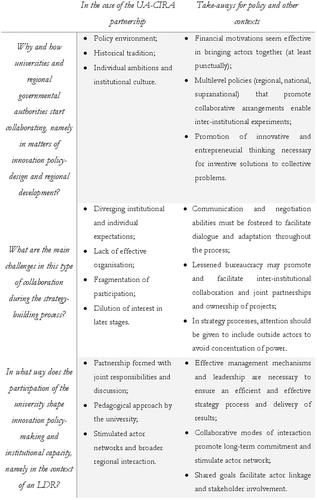

Why and how universities and regional governmental authorities start collaborating, namely in matters of innovation policy design and regional development?

What are the main challenges in this type of collaboration during the strategy-building process?

In what way does the participation of the university shape innovation policy-making and institutional capacity, namely in the context of an LDR?

The next section presents the case and methods used to examine the policies co-design processes.

METHODOLOGY

The methodological framework is qualitative and interpretative. It seeks to gain insight into the experiences of groups and individuals regarding innovation policy processes in which UA and CIRA partnered in. Specifically, two territorial development programmes, the first corresponding to the 2007–13 period (PTD) (Grande Área Metropolitana de Aveiro & UA, Citation2008) and the second to 2014–20 (EIDT) (CIRA, Citation2014). A case study method enables more in-depth exploration, triangulation of data and interpretation of results. While illustrating a particular set of conditions and relationships, there is potential for analytical generalization allowing one to extrapolate logically to theory and social processes in other contexts (Yin, Citation2009).

Data collection combines policy documents, reports and statements of both UA and CIRA. In addition, 18 in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with university academics and top managers, policy-makers and other actors involved in the strategies. This allowed for an enlarged perspective of the process itself. Interviewees’ selection considered whether they had participated in at least one of the strategy design processes, or whether they managed in some other form the UA–CIRA relationship. It included both top managers and technical staff. To acquire reliable information on the process, it was important to consider that the interests involved, especially from top managers, might skew the openness in delving upon certain topics. Moreover, routinely working on strategy-building and project management inevitably confers different perspectives on achievement. Therefore, consulting both technical and managerial-type staff was necessary for a broader perspective. Equally, interviewing other regional stakeholders, for example, business associations and intermediate offices, conferred other perspectives on the collaboration. Their selection was based on regional relevance and/or their role as intermediates in other projects with UA and CIRA. At the time of writing, six interviews were conducted with policy-makers and technical staff, seven with academics, two with intermediate offices, associated with municipalities or UA, and three with business associations.

Interviews were recorded with an average duration of one hour. Questions included how strategies’ design process took place; in what consisted UA's participation and what were the expectations involved; and what benefits or tensions emerged from this collaboration. Collected data were transcribed and coded by identifying persistent and relevant themes. To address the research questions, analysis focused on motivational and contextual factors that enabled the partnership; emerging institutional, organizational and/or interpersonal tensions; and perspectives on UA's participation and its meaning for policy and regional development. Conclusions were drawn from these sources through content and thematic analysis, permitting detailed and contextual documental examination.

A case of innovation co-design

The UA was chosen given the particularities of the region in which it is situated (), the context of its establishment and the discourse of regional embeddedness and innovation surrounding it. This was reinforced by previous accounts in the literature (Rodrigues et al., Citation2001; Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013; Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017; Rosa Pires, Pinho, & Cunha, Citation2012) reporting on punctual collaborative experiments carried out between the UA and local or regional government.

Figure 1. Portugal with the NUTS-II administrative divisions and the NUTS-III Aveiro region highlighted.

Source: Adapted from figure at Wikimedia Commons.

First, the Aveiro region refers to the agglomerate of 11 municipalities in the Portuguese Centro region's coast, and it is loosely equivalent to the NUTS-III level. It is classified as less developed according to the EC's Cohesion framework.Footnote1 Mostly economically based on agriculture until the 1970s, and located between the metropolises of Porto and Lisbon, its peripherality in a highly bipolarized country contributes to this categorization. Nevertheless, its industrial development, aided by UA's creation in 1973, has granted Aveiro district the third highest performance in relative weight in gross domestic product (GDP) and exports (Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017). Its industry is highly relevant in the areas of ceramics and materials, agro-food, forestry, information and communication technology (ICT), sea and environment, and metallurgy, with several national leading companies. It is predominantly built of low-tech small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), however, and it can be considered sectoral and geographically diffused, with no distinctive urban area anchoring industry and with this being practiced concurrently with agriculture (Rosa Pires, Citation1986).

Second, the context of the UA's creation was one of growing international competition which required massification of higher education and economic regeneration in Portugal. With increasing government investment for new universities to circumvent the Lisbon, Coimbra and Porto tryptic, there was a demand from the Aveiro region to have one established there. The UA started in the Innovation Centre of Portugal Telecommunications, with its curriculum first consisting of ICT, ceramics and environmental studies, aligned with the regional economy. Created to respond to local needs, this inevitably shaped its regional mission and association with innovation and technical areas. While this has materialized in a more technology-based knowledge transfer and entrepreneurial model of engagement, in recent years it is argued UA has been shifting to a more civic model with a wider regional focus (Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012).

Third, previous studies on regional government–university–industry interplays (Rodrigues et al., Citation2001; Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013; Rodrigues & Teles, Citation2017; Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012) have been elucidating but punctual in nature. Earlier joint projects cemented the UA–region link, namely a collaboration with a municipal association in 1989, the Municipal Association of the Ria of Aveiro (AMRIA) in matters of environmental pollution. Cooperation between the UA and individual municipalities flourished in the early 2000s, with punctual Triple Helix-based regional innovation experiments (Rodrigues & Melo, Citation2013). These paved the way for the more recent collaboration in strategy-making. This effort was encouraged by ERDF requirements, which the Regional Coordination Commission of the Centro Region (CCDRC) at the NUTS-II level could delegate to the intermunicipal (NUTS-III) level, providing a territorial development strategy was designed (Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012).

Given the characteristics described above, the case study here presented can be analyzed to answer the aims proposed. Namely, to understand what are the triggering factors for universities and regional government to start collaborating on innovation governance and policy design, how this engagement is managed, and why the nature of collaboration is given to a greater or a lesser proximity and continuity. Finally, what the implications of such an arrangement are for regional innovation and institutional capacity. The following section presents the findings, followed by an interpretation of their relevance in this context.

RESULTS

The findings are presented to understand the partnership's establishment, the involved tensions and UA's role in innovation policy and institutional capacity-building in the Aveiro region. Through the analysis of strategy documents, the territorial development programme (PTD) (Grande Área Metropolitana de Aveiro & UA, Citation2008) and the integrated territorial development strategy (EIDT) (CIRA, Citation2014), both institutions’ websites,Footnote2 and interview data, relevant themes have been identified, granting this section the following structure: first, influencing factors for the establishment of the partnership will be stated, accompanied by the institutional response to the partnership, helping one to understand relevant triggers for the institutions’ rapprochement; second, emerging challenges throughout the process are identified for a clearer comprehension of pitfalls; and finally, some outcomes and regional implications of the partnership are listed.

Forging the link between the university and local and regional government

Context, motivations and efforts

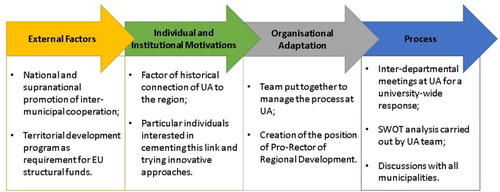

Imbued upon its creation with regional expectations especially regarding industrial regeneration, the UA has characteristically focused on industry cooperation with an entrepreneurial approach. It is pertinent to question then why UA and CIRA partnered in matters of public policy, and how this process developed. Three main motivators are identified: the policy environment, a historical connection and appeal to a regional mission, and institutional and individual ambitions.

Policy environment. Aveiro region has witnessed a few collaborative and associative experiments throughout the years. In 1989, 10 municipalities banded together under AMRIA to face a shared environmental problem of water pollution. It was also one of the first experiments of working with UA, particularly its environmental sciences department. Then, in 2007, the national and supranational level were promoting sub-regional associative experiments: EU guidelines based on the Lisbon Agenda promoted sub-regional intermunicipal partnerships and the adoption of new methodological approaches to governance and policy-making (Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012); and nationally, administrative policies encouraged municipal associations at the NUTS-III level, concomitantly granting them partial management of the ERDF. In this environment, 11 municipalities of the Aveiro region came together for a more permanent associative experiment – CIRA, the intermunicipal community of the region of Aveiro. Political and financial factors were thus prominent. Depending on the elaboration of a territorial development programme to access regional funds, CIRA decided to resort to the UA's expertise, concluding its knowledge and resources would represent an advantage.

History and regional mission. UA’s historical predisposition toward regional needs facilitated CIRA's first approach. The UA had previously collaborated with AMRIA in solving pollution problems, but it had also worked with single municipalities in a variety of issues (e.g., education, health, planning). While interviewees argued there was a potential lack of strategic and unified vision on UA's part, these small initiatives slowly built a more transformative and enduring relationship between the two institutions. The ‘historical commitment towards the future of the region’ is referred in the agreement signed between the two (UA & CIRA, Citation2012, p. 1), and is a part of both institutions’ discourses (websites, reports, policy documents).

Individual doers. The third motivating factor for a UA–CIRA partnership is related to the role of key individuals. In both institutions, leading actors (not necessarily top management) interested in contributing to the region and advancing UA's role enabled the agreement to occur and developed it to the present fully fledged partnership. As an interviewee in an intermediate position explained, ‘the engine is often in one person’, mirroring other interviewees’ emphasis on the importance of leadership for the process. Namely, as an academic mentioned, ‘it was a good coincidence, that at that time we had motivated people both from CIRA and UA that wanted to get this going, that wanted to make this work’.

Contextual conditions therefore made this partnership possible, but willed interventions by individuals were key. While intermunicipal cooperation was enacted in the whole country, and multilevel political obligations and financial opportunities propelled a strategy, collaboration with the university was enabled in Aveiro by a shared vision of innovation.

Institutional and organizational adaptation

Regarding how both institutions started cooperating in regional strategy-making, a contrast is immediately identified between policy-makers and academics. In interviews, the latter suggest UA wanted to get closer to the region and assumed a leading role in this partnership. Policy-makers, on the other hand, point out it was their initiative to involve UA. As one CIRA employee humorously recalls asking at the time the agreement was proposed, ‘does UA want to dance with us?’. The proposal to have a (local) university involved in the process departed from CIRA, a decision uniquely divergent from that of other intermunicipal communities in Portugal at the time, who selected a consultancy firm for the strategies’ redaction. As a policy-maker denoted, ‘we were eager to make something different, and something different is [ … ] to try a new agenda’, which existent consultancy firms were not providing. Specifically, a single consultancy firm was mentioned as doing other regions’ PTDs in 2007, and the policy-maker emphasized CIRA's will to reject ‘copy–paste’, ‘try something different’ and involve UA, ‘who has the responsibility’ to realize this. Nonetheless, UA proposed a closer partnership, with shared responsibility and costs, and this was accepted despite potential bureaucratic and administrative challenges in joint ownership.

Proposal agreed, the UA prepared a team of experts, both researchers and rectory staff, which would oversee the project. Interviewees referred to this step as crucial, emphasizing individuals’ roles, on both sides, in guiding and mediating and giving the process vision. One such case was the Pro-Rector of Cooperation and Regional Development, a position created expressly by the UA's then rector to manage this process and act as point of contact between the UA and local and regional government. By creating these organizational facilitators, UA thus made efforts towards adapting to this new responsibility in regional engagement and policy-making.

UA was responsible for assessing the regional context through technical evaluations. While including other stakeholders in the process was a shared task among partners, UA's team was the main facilitator. It attempted to involve all university departments in brainstorming meetings, with 50–100 academics, to ascertain internal interest and tackle how collaboratively to respond to CIRA's needs. Meetings in each of the 11 municipalities were also organized, where UA's team provided assessed results and mediated between local stakeholders in deliberative forums ().

Emerging challenges

Scepticism and political interest

While significant motivating factors were involved, inter-institutional collaboration was not straightforward. As mentioned, CIRA was the one approaching UA to engage collaboratively in strategy-making. However, the joint leadership suggested by UA led several mayors to consider it as dangerous to the (highly politicized) policy-making process (Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012). Several interviews with both policy-makers and academics suggest hesitation related to a resistance to doing things differently, a certain mistrust in academics’ way of working and in evolving towards a joint ownership. According to a CIRA representative, for the first time voting was not consensual, and the partnership close to not happening, with six municipalities in favour and five against. This led to tensions in the initial stages, concessions and the departure of certain academics from the project. Overcoming initial suspicion to move towards closer engagement modes was a concern for academics:

The very first big meetings, it was a struggle for us […] to make them trust us, make them know that we might be useful in ways that they weren't aware of. […] Difficult initial phase, […] not only because of the knowledge, or the lack of understanding, also because of the lack of communication.

These initial fragilities relate to the tendency for concentrations of power in policy environments (Aranguren et al., Citation2009). By sharing the project and policy arena with the UA, municipalities in CIRA inevitably abdicated part of their political power and image. As is evident by this quotation from a policy-maker: ‘Of course, the university read it as something fantastic for the university role. We said “ok, that's our work, our vision that was analyzed”, but ok.’ Entering the field of politics was difficult for the UA to manage, with this statement by an academic exemplifying that even within CIRA relationships could be tense: ‘the major problem are the political relationships. This sometimes is what prevents things from going further. [ …] The relationship between mayors. If they even have a relationship’.

Fragmented participation and managing expectations

While academics and policy-makers alike emphasized the participative nature of discussions, with the involvement of both industries and third-sector organizations, statements from other interviewees suggest this was not as meaningful as expected. One from a business association expressed dismay in participating, asking: ‘Why should I work and try to work together if I’m just there to mark my presence?’ As most interviewees stated, the strategies being under the tutelage of two big institutions, CIRA and UA, limited other actors’ influence in the process. The inclusion of the Aveiro District Industrial Association (AIDA) in the period 2014–20 as the managing entity for the structural funds in the region did little to change opinions. It was also unclear whose role it was to incorporate other actors, with policy-makers attributing that task to the UA, but with a consensus that ‘municipalities know what their people want’, implying little need to get too much input. As one academic stated, for UA ‘the major concern were the mayors. [ …] The main actor that defined the main strategic dimensions of the regions were the mayors’.

Fragmentation could be accounted to university participation as well. When questioned about UA's engagement in the project, one academic stated: ‘what we had was many people and departments interacting with regional entities, firms, municipalities and so on, but not very institutionalised [ … ] it was not the institution but professor X in the department Y acting like this’. Policy-makers had a matching perspective: ‘It's not the university. [ … ] It's who at the university [ … ]’. Furthermore, a policy-maker considered UA's input in the design process as uneven and insufficient, more pronounced in the formulation phase than in the implementation and evaluation phases, where it is diluted and inconsistent. An academic also stated, ‘In the design phase, there was a strong presence [from the university] and a great level of interaction. But then in the implementation phase [ … ],’ suggesting an uncomfortable agreement with the policy-maker's statement.

Outcomes and implications

In the projects

Several resulting projects from the strategies in both periods included or were managed by UA. Two of the most frequently highlighted by interviewees are the Urban Network for Competitiveness and Innovation (RUCI) and the Business Incubator of the Region of Aveiro (IERA). Their relevance was stated as relating to the number of actors involved, the potential outreach and incorporation of different policy fields, funding attributed and the alignment with regional and national objectives.

RUCI. A PTD project, in 2011 the RUCI of Aveiro region was developed seeking to contribute to the competitiveness and sustainable development agendas. It was framed under the national programming framework, and intermunicipal communities adopted it. In Aveiro region investment amounted to €9 million, €5.9 million of those in ERDF. In total, there were 11 partners in the project, which the UA co-led with CIRA. UA's participation led to the enlargement of typical innovation domains: aside from entrepreneurial promotion and economic growth, Aveiro's RUCI presented a new agenda for health and well-being, sustainability and culture, the latter combining arts and ICT for a ‘Culture in Network’ programme. UA thus enabled the incorporation of creative elements into the conception of regional development.

IERA. Emerging from the EIDT in 2016, IERA is a network of 11 incubators throughout the CIRA municipalities, also co-funded by the ERDF. It is a strategic institution undertaken by the CIRA, UA and AIDA, with the objective of promoting entrepreneurship, social innovation and economic development in the region. UA's incubator is IERA's main hub and the nexus of contact. In principle, involved incubators should benefit from common resources, scientific knowledge and an integrated regional strategic vision. Practically, criticism of its organizational structure abounds, with little network dialogue occurring between incubators but rather centrally managed by UA. Nonetheless, IERA is considered to have boosted innovation performance in the region and remains one of the most distinguishing projects of the UA–CIRA partnership. The project has now the opportunity to evolve with the recent opening of the science and innovation park, where IERA will be stationed.

Institutional capacity-building

UA's engagement in the process was consensually believed to have shaped the regional innovation setting. By providing guidance, mediation, mentoring and a new outlook into how innovation is thought about in the region, UA gave the strategies focus, and imbued them with knowledge and creativity. As one academic summarized, ‘I think this was a major progress in terms of what they [municipalities] understood might be a collaboration between the University and the system [ … ].’ Material outcomes were rarely mentioned in interviews, with respondents rather emphasizing the opportunity the partnership brought for a regional collaborative framework in innovation to be developed. This implies UA's engagement enlarged the realm of possibilities in innovation policy and practice in the region, perhaps creating new development pathways. It promoted new ideas and approaches, which nationally distinguished Aveiro region (Rosa Pires et al., Citation2012).

In the governance sphere, an academic interviewee emphasizes this capability of UA: ‘We are in fact contributing to improve the capacity of policy-makers in the region. We are contributing to regional development through the provision of knowledge.’ The knowledge of the multilevel policy environment and regional dynamics, as well as UA's pedagogical approach throughout the process, was considered as crucial to policy-makers. One stated ‘there is a clearer guidance’ for territorial development since the partnership, with UA having the role ‘to keep us working within the framework, because we have the tendency to get out of it and try [ … ] and work as we can’. UA's guidance implied an increase in the opportunity for municipalities to capture more resources from the regional and national authority, and promoted more informed policy-making.

Similarly, it suggests a capacity to stimulate learning dynamics and organize actors and resources for a common goal. As a policy-maker denoted, the UA's capable of assembling political actors and activating mechanisms in a way they had not been able to do before: ‘There is a work that the university can do for us, which is mobilise us, that is, create conditions for us to operationalise, [ …] materialise our objectives.’ UA's ability to build institutional capacity in the region through this collaborative experiment is likewise described by an academic: ‘[what was most important] was in fact the effort made to put the university working together with municipalities, with other institutional settings, like the regional commission’. However, the same academic warns that priority definition and implementation must be an equal priority, so that action is not relegated to the background, behind dialogue and image.

DISCUSSION

The findings presented above, the result of a case study exploration of collaborative policy-making for regional development between UA and CIRA, have illustrated the motivators for university–regional government partnerships, the main barriers that can emerge in attempting such a collaboration, and the potential benefits in this linkage for the innovation imaginary of a region. This structure, mirroring that of the research questions, is continued below, linking the interpretation of the findings with the literature.

First, regarding how universities and regional government authorities start collaborating in an innovation policy process, it seems clear that the motivating factors found mirror Aranguren et al.’s (Citation2009) emphasis on local context, policy environment, institutional culture (adapted to include individual ambitions) for the enabling of a collaborative initiative. An external impetus and shift in the policy environment, as well as particularities of the regional historical and institutional context of collaboration, were determinant in UA and CIRA coming together. Individuals with a specific vision, ambition and/or cultural predisposition for engaging then allowed them to stay together. UA's academic culture, with a discursive emphasis on a regional mission, facilitated active interest of key people in the process. Individual ambition was included here given academic engagement is not necessarily institutionally centred, but can rest on top managers and/or entrepreneurial individuals (Chatterton & Goddard, Citation2000).

Regarding these triggering factors, two takeaways should be considered in future studies. First, financial opportunities and a multilevel push from regional, national and supranational authorities were important to propel and structure the territorial programme, giving the partnership sense and shared objectives. Funds’ accessibility, though materialistic in nature, is a common necessity for institutions, especially in LDRs, but the inclusion of an institutional partner like a university was not required, highlighting the existence of other preconditions to promote these partnerships. Consequently, and second, innovative thinking on the part of actors and institutions involved may provide the necessary step towards transforming governance arrangements and normalizing collaborative dynamics. As mentioned, CIRA sought new approaches for policy design and regional development, leading toward the collaboration; the UA was equally eager. A cultivation of entrepreneurialism, in the region but namely in these institutions, as well as a relative openness in the milieu to new ideas, can foster the formation of these linkages.

Second, considering the challenges that can emerge in inter-institutional collaboration, interviews suggest this was convoluted. Academics left the team due to divergences in approach, and different expectations were highlighted as a factor. Policy-makers were hesitant to share the project, with some showing caution regarding potential predominance of UA, in a certain level of technocracy or usurpation of political image. These initial fragilities in the partnership and strategy-making process can relate to the tendency for concentrations of power in policy environments (Aranguren et al., Citation2009).

Another challenge was found during the process itself. There was dismay in UA's lack of interest and support in the later stages, with a heavy input in the formulation phase with staff, research and guidance, but with little involvement in the implementation and monitoring phases. Results in regional development may therefore not have been maximized. Lack of UA's presence in these later stages also suggests a wider problem: the gap between policy and practice. Multilevel policies, as well as diverse actor inputs, add complexity to this, and for some disappointment, and outcomes fell short of initial aspirations.

Ultimately, emerging challenges can be summed up as a lack of effective communication on both sides, which can hamper the management of diverging expectations regarding the sharing of responsibilities and benefits. As a highly fragmented institution, the inclusion of the university was difficult. Entrance into the policy sphere, once granted, can also come with limitations in participation and adaptation to political programmes, requiring some negotiation ability. The increased bureaucracy in inter-institutional partnerships, along with a multilevel alignment involved in regional policy-making, can lead to hesitancy in collaboration and a fading interest throughout the process. This hinders implementation and requires continued adaptation of strategy and outcomes. Increasing awareness of these dilemmas might thus help improve actors’ reflexivity and contribute towards a more effective process.

Third, concerning how universities’ participation can shape innovation policy-making and institutional capacity, namely in an LDR, it is important to notice that notwithstanding disagreements in approach and initial mistrust, both institutions were able to build on this through a joint exploration of solutions to common problems (Morgan & Nauwelaers, Citation1999; Nicholds et al., Citation2017), building a more long-term commitment. This mirrors Aranguren et al.’s (Citation2009) argument that an ‘action research’ approach gives way to more consistent interaction between actors. The UA gained a relevant role in the policy process by using its knowledge, resources and capabilities for the mobilization of the wider institutional and innovation landscape. It helped support and manage a regional network by strengthening and mediating dialogue and used a pedagogical approach, thus stimulating learning dynamics and innovative thinking (Aranguren et al., Citation2009; Gunasekara, Citation2006b; Pugh et al., Citation2016).

While it is still too early to assess the strategies’ effects on regional development and innovation, in institutional capacity-building the steps taken led the region in a good direction. The lack of interaction between institutional agents – a challenge in LDRs (Huggins & Johnston, Citation2009; Rodrigues et al., Citation2001) – has started to be tackled, and the university has played a major role. Effective management mechanisms and leadership were key in fostering collaboration in this LDR. More generally, this study proposes university–regional government's collaboration for innovation policy design to be of great value in various contexts. It is apparent that connecting institutional actors with regional development as a goal is, at least, a worthy pursuit. Findings suggest this enabled more comprehensive and long-term learning dynamics to occur and created opportunities for the unlocking of institutional and innovative capacity.

Albeit a set of circumstances have contributed to the current collaborative framework in Aveiro, this analysis can inform policy-makers and academics in other contexts about the potential benefits and opportunities in participating in a closer form of engagement in policy-making and governance activities (). Its contribution to the previously mentioned literature through its more extensive, in-depth perspective has hopefully provoked a more active discussion on this oft-overlooked form of engagement, for a more thoughtful and reflexive approach.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper has explored the nature of collaboration in matters of policy design between a university (UA) and a regional authority (CIRA) in the context of the design of territorial development strategies in an LDR: the region of Aveiro, Portugal. The UA's role in the Aveiro region's strategy process was the result of a long worked-on collaborative link. CIRA amiably pressured the university to respond to its needs, and institutional mechanisms were created for this knowledge transfer to occur. While perhaps the partnership has not been fully profited upon, with further room existing for UA to engage more actively in the implementation and evaluation stages of the process, the UA–CIRA partnership has greatly furthered development goals in a less-favoured context, with the strategic plan strengthening institutional ties.

Several of the findings mirror the literature concerning influencing factors for engagement and collaboration, barriers and the potential of collaborative modes of interaction in stimulating stakeholder networks and learning dynamics. While universities’ role in building institutional capacity has been acknowledged in the literature, the exploration of this role in the context of two strategy-design processes in which the university was a de facto partner of the regional authority is valuable to enrich the field. Some of the motivating factors identified, such as the policy environment and the access to funds, can carry potential implications for future programming periods. But while circumstances might normalize collaboration, only human agency and dialogue can channel effectiveness and learning. A communicative, pedagogical and adaptive approach to align stakeholders better over time seems key. This is what allowed the UA to guide and mediate the process and unlock regional institutional capacity and innovative thinking, presently shaping the region. And it is important when seeking to cultivate collaborative dynamics in an LDR.

This paper expands on the under-researched topic of universities’ regional engagement in governance activities, and chiefly in innovation policy design, by providing an extensive, in-depth and long-term perspective on a partnership between a university and a regional authority in strategy design. By illustrating influencing factors and barriers for the effectiveness of the partnership, it approaches a relevant topic not just for academics but also for policy-makers seeking to develop such collaborations. Its contribution to the fields of innovation, higher education and planning can be further expanded upon by analyzing more specific territorial dynamics and particularities of LDRs, as well as engagement limitations for universities and academics in this type of engagement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The feedback by Professor Rune Dahl Fitjar and Professor Carlos Rodrigues for the completion of this paper is greatly appreciated.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Liliana Fonseca http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9041-0921

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For more information on this categorization, see http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/what/future/img/eligibility20142020.pdf.

2 CIRA': http://www.regiaodeaveiro.pt/; UA': http://www.ua.pt/.

REFERENCES

- Aranguren, M. J., Larrea, M., & Wilson, J. (2009). Academia and public policy: Towards the co-generation of knowledge and learning processes. Orkestra, 2009-03, 1–31. Orkestra Working Paper Series on Territorial Competitiveness.

- Arbo, P., & Benneworth, P. (2007). Understanding the regional contribution of higher education institutions (OECD Education Working Papers No. 9). Paris. doi: 10.1787/161208155312

- Beer, A., & Clower, T. (2014). Mobilizing leadership in cities and regions. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 5–20. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2013.869428

- Bonaccorsi, A. (2016). Addressing the disenchantment: Universities and regional development in peripheral regions. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 1–28. doi: 10.1080/17487870.2016.1212711

- Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2009). ‘Mode 3’ and ‘quadruple helix’: Toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International Journal of Technology Management, 46(3/4), 201. doi:10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374

- Chatterton, P., & Goddard, J. (2000). The response of higher education institutions to regional needs. European Journal of Education, 35(4), 475–496. doi: 10.1111/1467-3435.00041

- CIRA, & UA. (2014). Estratégia de Desenvolvimento Territorial da Região de Aveiro 2014–2020. Aveiro: CIRA | Universidade de Aveiro.

- Drucker, J., & Goldstein, H. (2007). Assessing the regional economic development impacts of universities: A review of current approaches. International Regional Science Review, 30(1), 20–46. doi: 10.1177/0160017606296731

- Etzkowitz, H. (1990). The second academic revolution: The role of the research university in economic development. In S. E. Cozzens, P. Healey, A. Rip, & J. Ziman (Eds.), The research system in transition (pp. 109–124). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. doi: 10.1007/978-94-009-2091-0_9

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “mode 2” to a Triple Helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- Foray, D., David, P., & Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialisation – The concept. Knowledge for Growth Expert Group. Retrieved from http://cemi.epfl.ch/files/content/sites/cemi/files/users/178044/public/Measuring%20smart%20specialisation.doc

- Goddard, J., Coombes, M., Kempton, L., & Vallance, P. (2014). Universities as anchor institutions in cities in a turbulent funding environment: Vulnerable institutions and vulnerable places in England. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 7(2), 307–325. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsu004

- Grande Área Metropolitana de Aveiro, & UA. (2008). Programa Territorial de Desenvolvimento para a Sub-região do Baixo Vouga. Aveiro: Grande Área Metropolitana de Aveiro | Universidade de Aveiro. Retrieved from http://www.maiscentro.qren.pt/private/admin/ficheiros/uploads/PTD_BAIXO%20VOUGA.pdf.

- Gunasekara, C. (2006a). Reframing the role of universities in the development of regional innovation systems. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 31(1), 101–113. doi: 10.1007/s10961-005-5016-4

- Gunasekara, C. (2006b). Universities and associative regional governance: Australian evidence in non-core metropolitan regions. Regional Studies, 40(7), 727–741. doi:10.1080/00343400600959355

- Hirschman, A. O. (1958). The strategy of economic development. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Huggins, R., & Johnston, A. (2009). The economic and innovation contribution of universities: A regional perspective. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(6), 1088–1106. doi: 10.1068/c08125b

- Morgan, K., & Henderson, D. (2002). Regions as laboratories: The rise of regional experimentalism in Europe. In M. S. Gertler & D. A. Wolfe (Eds.), Innovation and social learning: Institutional adaptation in an era of technological change (pp. 204–226). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi: 10.1057/9781403907301_10

- Morgan, K. J., & Nauwelaers, C. (1999). A regional perspective on innovation: From theory to strategy. In K. Morgan & C. Nauwelaers (Eds.), Regional innovation strategies: The challenge for less-favoured regions (pp. 1–17). London: Routledge.

- Nicholds, A., Gibney, J., Mabey, C., & Hart, D. (2017). Making sense of variety in place leadership: The case of England’s smart cities. Regional Studies, 51(2), 249–259. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1232482

- Pugh, R., Hamilton, E., Jack, S., & Gibbons, A. (2016). A step into the unknown: Universities and the governance of regional economic development. European Planning Studies, 24(7), 1357–1373. doi:10.1080/09654313.2016.1173201

- Rodrigues, C., da Rosa Pires, A., & de Castro, E. (2001). Innovative universities and regional institutional capacity building: The case of Aveiro, Portugal. Industry and Higher Education, 15(4), 251–255. doi: 10.5367/000000001101295740

- Rodrigues, C., & Melo, A. I. (2013). The Triple Helix model as inspiration for local development policies: An experience-based perspective: The Triple Helix model and local development in Portugal. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 37(5), 1675–1687. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01117.x

- Rodrigues, C., & Teles, F. (2017). The fourth helix in smart specialization strategies: The gap between discourse and practice. In S. P. De Oliveira Monteiro & E. G. Carayannis (Eds.), The quadruple innovation helix nexus (pp. 205–226). New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-55577-9

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rosa Pires, A. (1986). Industrialização Difusa e ‘Modelos’ de Desenvolvimento: Um Estudo no Distrito de Aveiro. Finisterra, 21(42), 239–269. doi: 10.18055/Finis2025

- Rosa Pires, A., Pinho, L., & Cunha, C. (2012). Universities, communities and regional innovation strategies. Presented at the 18th APDR Congress: Innovation and Regional Dynamics (pp. 337–343), Faro.

- UA, & CIRA. (2012). Contrato de Parceria Institucional ‘Melhor Cooperação, Mais Futuro’. The UA.

- Uyarra, E. (2010). Conceptualizing the regional roles of universities, implications and contradictions. European Planning Studies, 18(8), 1227–1246. doi:10.1080/09654311003791275

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.