ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the main forces driving economic integration in cross-border regions (CBRs). Drawing on the proximity framework, it contends that all four forms of proximity need to be stressed in cross-border regional economic integration discourses. The paper is based on a comparison of two cross-border regional contexts in North America, which have been investigated using a survey and semi-structured interviews. Based upon the data collected, the two case studies shed a light on cognitive proximity as an underestimated driver in CBRs. Moreover, the cross-border regional identity as well as the access to a talented workforce emerge as remarkable assets to leverage through appropriate cross-border regional policies.

INTRODUCTION

The aim of this paper is to gain an improved understanding of the main drivers of regional economic cross-border cooperation. This discussion merits attention at present because cross-border regions (CBRs) are deemed as ‘locations of competitive advantage in the global economy’ (Vance, Citation2012, p. 5). Therefore, this study sheds a light on the unlocked economic potential of CBRs (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2013). Adopting a twofold perspective, this research moves forward the theoretical state-of-the-art demonstrating the roles of proximity (Boschma, Citation2005) in CBRs as a neglected topic (Trippl, Citation2010). In addition, this timely analysis can inform policy recommendations for CBRs on the basis of the economic drivers evaluated.

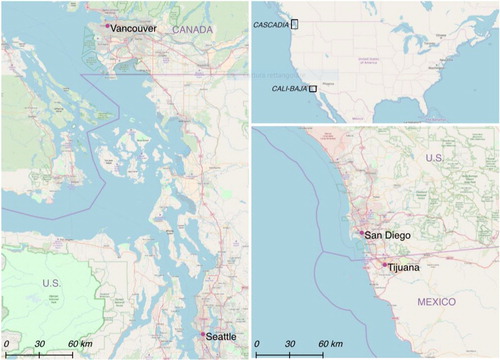

The study is based on a comparison of two CBRs: ‘Cascadia’ on the US–Canadian border; and ‘Cali-Baja’, the urban agglomeration around San Diego (California) and Tijuana on the US–Mexican border ().

The authors selected the two case studies using the following criteria: (1) the prominent role both CBRs play in the high-innovation economies, where the framework adopted in this analysis – proximity – is more significant (Balland, Boschma, & Frenken, Citation2015; Boschma, Citation2005); (2) the common regulatory framework (e.g., USMCAFootnote1) ruling on both CBRs; and (3) a longstanding tradition in cross-border cooperation (see the bilateral memorandums of understanding (MoUs) signed) in the two CBRs.

Thanks to their similarities and differences, these two CBR cases may allow the findings to be applied in other CBRs. In each context, a diverse panel of actors has been surveyed to identify which are the most important drivers pushing economic development in the CBRs. A qualitative and quantitative approach has been adopted in order to corroborate the results in the light of the cases’ specificities. The two case studies reveal access to external resources as the utmost driver. Notwithstanding common aspects, they show different outcomes, including the importance of cross-border regional cultural identity as an economic driver as well as the fine-tuned workforce in terms of talent and skills.

PROXIMITY IN CBRs

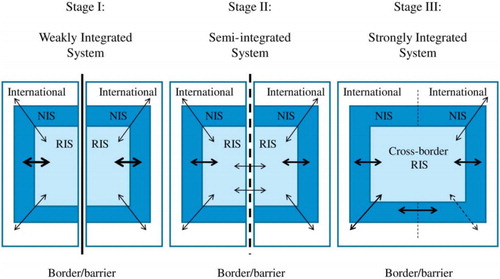

In the field of economic geography, CBRs are ‘a bounded territorial unit composed of the territories of authorities participating in a cross-border cooperation initiative’ (Perkmann, Citation2003, p. 157). The seminal work of Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013) outlined the cross-border regional innovation system (CBRIS) model. Based on the proximity framework, the model () draws three ideal stages of CBRs from the most fragmented to the full integrated, where the border – interpreted only as a barrier – disappears completely. In this CBRIS view, the extent of cross-border integration is highly dependent on the degree of proximity in the CBR. Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013) do not clarify the types of proximity that matter in CBRs nor the outputs in the field of Science & Technology cooperation that are affected by high levels of cross-border proximity (Makkonen & Williams, Citation2018). Although their study provides examples of CBRs to depict each stage, several scholars questioned the model. Major criticisms focus on the scope of the analysis (van den Broek & Smulders, Citation2015) and the nature of the knowledge flows (Muller et al., Citation2017).

Figure 2. Ideal types of different levels of cross-border integration. Source: Lundquist and Trippl (Citation2013).

Therefore, this research adopts a regional-scale approach to investigate better the CBRIS where knowledge flows generate innovation. In this regard, it evaluates empirically the degree of proximity (Boschma, Citation2005) in the two CBR case studies. In so doing, it uses qualitative and quantitative data to move forward the CBRIS theoretical framework.

Accordingly, the authors rely on the five dimensions of proximity: cognitive, organizational, social, institutional and geographical (Boschma, Citation2005). The CBRs enjoy competitive advantages since the geographical proximity to the border can enable the benefits of accessing complementary systems and environments (Vance, Citation2012) or chances to overcome local lock-in and bottlenecks (Hudec & Urbancikova, Citation2010). Nonetheless, geographical proximity does not necessarily lead to other forms of proximity (Lundquist & Trippl, Citation2013), including the cognitive proximity. In this regard, similar knowledge bases across the border favour the knowledge flows to be exploited in the CBRs (Muller et al., Citation2017).

Based on the ‘embeddedness’ literature (Granovetter, Citation1973), the relations among individuals/organizations, for example, ‘social proximity’, are considered as a precondition for interactive learning (Lundvall, Citation1992) – increasingly advocated in the innovation economies – as well as for the networks of (local) organizations that play a first-tier role in the cross border cooperation process (Blatter, Citation2004; Cappellano & Makkonen, Citation2019; Lundquist & Trippl, Citation2013). Institutional proximity recalls ‘the set of practices, laws, rules and routines that facilitate collective action’ (Lazzeretti & Capone, Citation2016, p. 5857). In CBRs, it can be interpreted as the capability of local institutions to set up a legal framework (e.g., cooperative agreements and memorandums of understanding) for cross-border integration (Ganster & Collins, Citation2017). Organizational proximity is not considered in this discussion since it refers to subsidiaries, units, departments or establishments within an organizational structure (e.g., corporate groups) (Balland et al., Citation2015).

METHODOLOGY AND CASE STUDY OVERVIEW

The study was conducted through a mixed approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data. The authors surveyed representatives from organizations active in the CBRIS, including public authorities, companies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), universities, incubators and accelerators (). This approach was chosen to emphasize the local scale where cross-border cooperation mostly occurs (van den Broek & Smulders, Citation2015). The survey form was tailored to each crossing direction. The roster of organizations surveyed was defined along with entrepreneurs and academics well rooted in the regions, consistently with previous studies (Cappellano & Makkonen, Citation2019). The sample represents the 74% of the total population of actors identified through the ‘snowballing technique’. While the survey provided quantitative data, the authors held semi-structured interviews with survey respondents to gain additional qualitative insights. Survey and interview administration lasted six months. They were held in 2017 in Cali-Baja and in 2018 in Cascadia, where the authors received a brokerage support to obtain more interviews.

Table 1. Interviewees per each case study.

In Cali-Baja, the large economic asymmetries across the border (Ganster & Collins, Citation2017) pushed Mexican immigration towards southern California. Latinos represent the highest minority population share in San Diego County (32% in 2010), which, in turn, shapes the local ‘bi-national’ culture. Historically, the region has represented a gateway between Latin America and North America. Besides, the longstanding cooperation through targeted financial programmes (e.g., the ‘Maquiladora programme’) sought to exploit the difference in labour costs. At the same time, those investments enhanced the knowledge base of the Mexican workforce. In fact, US-based companies have been expanding research and development (R&D) centres in Tijuana since the two sides of the CBR share common economic sectors (). Geographers have coined the term ‘cross-border metropolis’ (Herzog & Sohn, Citation2014) to define the urban agglomeration that straddles the border between San Diego and Tijuana. Therefore, the two city councils work closely to manage a broad spectrum of issues as set out in the MoU) signed in 2017. Public authorities, private stakeholders and NGOs are engaged in the cross-border cooperation process through different networks (Cappellano & Makkonen, Citation2019; Ganster & Collins, Citation2017), as represented in the .

Table 2. Overview of the two cross-border region (CBR) cases.

In Cascadia, the two sides of the border experienced a longstanding competition for trade with Asia and recently as world-class technology hubs. The larger geographical distance between the regional powerhouses, Seattle (Washington) and Vancouver (British Columbia, Canada), impedes tight relationships as in the southern California CBR. Recently, a new initiative called the Cascadia Innovation Corridor strives to build more connections in the region supporting innovation economies. Supported by world-class private companies, the public authorities funded the feasibility study for a large transportation project (e.g., the high-speed train) to link the two main cities, Seattle and Vancouver. Additionally, the public authorities at the state level signed a MoU expressly pointing at ‘innovation economies’. Nonetheless, the two metropolitan statistical areas (Vancouver and Seattle) feature overlapping cluster portfolios. The ‘hardening’ of US immigration policy in the aftermath of 9/11 generated the opportunity for US-based companies to open departments in Canada to hire an international workforce.

The two regions possess substantial economic, social and geographical differences as well as experiencing different historical cross-border cooperation processes. However, it is viable to compare these cases since both regions are: (1) competing in innovation economies; (2) relying on (local) cross-border networks to spur economic development; and (3) complying with ‘hardened’ US immigration policy. These commonalities and differences allow the findings to have broader implications for CBRs in other contexts.

DISCUSSION

Geographical proximity

Respondents identify geographical proximity as a remarkable economic driver in both CBRs, although it is more appreciated where the spatial distance is closer – Cali-Baja – than in Cascadia where the distance from Seattle to Vancouver is 225 km.

Cognitive proximity

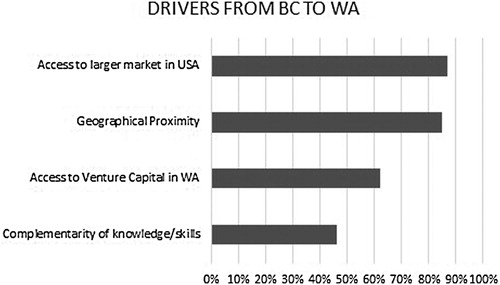

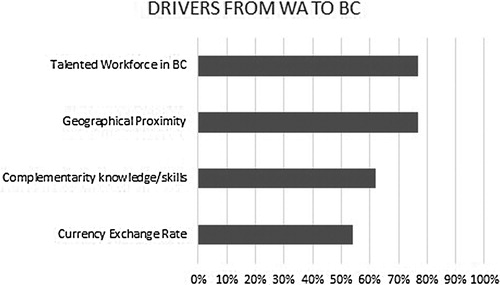

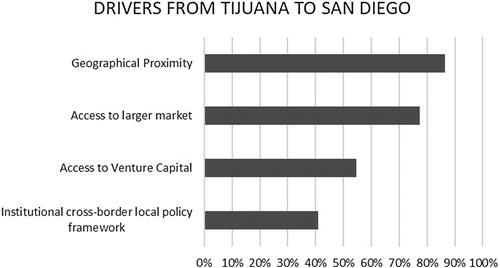

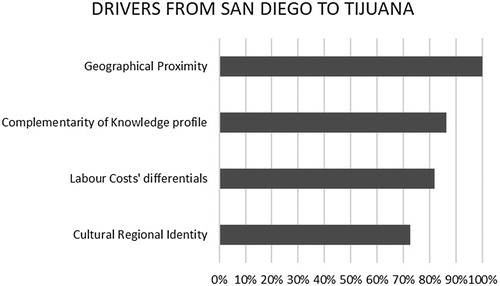

According to the proximity framework, the workforces’ complementarity of competencies – cognitive proximity – has been identified as the most important driver for innovation also in the CBRs, beyond geographical proximity. In Cascadia, the availability of a talented labour pool is perceived as the first-tier driver for US companies moving upwards to British Columbia. In fact, Amazon, Microsoft and other world-class information technology multinational enterprises recently opened departments to hire Canadians as well as internationally trained people, since Canadian immigration policy offers advantages in streamlined visa-issuing procedures and Canadian officials ‘being facilitative towards NAFTA [North American Free Trade Agreement] status applicants’ (Richardson, Citation2017, p. 227). In Cascadia there is a strong cross-border collaboration in the field of oncology where scientists ‘are working in the same research area. Leaders work proactively towards collaboration with US peers … when you are aware about opportunity, you tend to collaborate more’, as explained by a scientist interviewed. In Cali-Baja, finely tuned competencies of the workforce are ranked higher than labour cost differences (). Interviewees recognized that R&D capacities in the United States as well as the abilities to carry on the production process in Mexico provide excellent assets along the value chain in the CBR.

Social proximity

Moreover, the cultural identity, evident in the Californian case, works as a remarkable asset from an economic perspective. The interviewee emphasized a common cultural base in the CBRs. Young Mexican generations grew up with American television (covering the whole CBR region), which in turn improved their English-language skills. On the contrary, the local football (soccer) team of Tijuana attracts supporters from San Diego for a non-traditional US sport. This ‘binational identity’ reflects embedded values within a community (Granovetter, Citation1973) hinting at high social proximity. In this regard, several respondents acknowledged daily interpersonal and business ties with peers on the other side of the border.

Institutional proximity

Despite large differences in historic cross-border cooperation processes, the local policy frameworks (e.g., the institutional proximity) represent a less evident driver in both case studies.

The differences between the two contexts let those findings be generalized to a broader spectrum of CBRs. For instance, Cali-Baja features larger economic asymmetries straddling the border than Cascadia. The first region is the context where labour cost differentials are perceived the most. At the same time, both Canadian and Mexican actors look to enter the wealthier US market.

In sum, the role of CBRs emerges clearly from this empirical analysis: they can offer competitive advantages since they can ensure access to external resources such as capital, labour and wealthier markets. In fact, large US venture capital's endowment represents an incentive for both Canadians and Mexicans to start business ties across the border. At the same time, Tijuana provides to US stakeholders a ‘hotbed where to test services and products suitable for the enlarging Latin American market’, according to an academic interviewee. Those findings encourage one to rethink cross-border regional innovation policies that need to be tailored using a comprehensive development vision. Fine-tuned talented workforces and hybridization of cultural assets are demonstrated drivers that need to be supported by the cross-border policies.

The four strongest drivers per each border direction are shown in .

CONCLUSIONS

This paper combines two timely research strands – CBRs and proximity – to present the economic potential of the CBRs. Based on data collected through a survey and interviews in two North American case studies, the analysis targets a fundamental gap in the knowledge: which types of proximity matter in CBRs (Trippl, Citation2010). Adopting a perspective at the intersection between academics and policy-makers, this study moves forward the state-of-the-art with a clear contribution.

First, it identifies the first-tier role of cognitive and geographical dimensions of proximity. In fact, this analysis gives merit to two remarkable drivers embedded in the cognitive extent of proximity: (1) the alignment of the skills and expertise of the workforce with the companies’ needs on the other side of the border; and (2) the talented endowment of the labour pool that triggers companies moving across the CBR.

Second, it pushes forward the CBRIS model (Lundquist & Trippl, Citation2013). Identifying the drivers of cross-border economic development, it redefines the role of the border as a catalyst for innovation rather than only as an impediment.

Third, translating the theoretical findings into insights for policy-makers, the authors suggest a reconsideration of cross-border policies. Investments in infrastructure to facilitate the transportation across CBRs (enhancing geographical proximity) should be followed by a commitment to promote organic development in those regions upon a shared agenda. Leveraging the assets revealed from this study, including human and social capital, would allow the fine-tuning of the supply/demand of knowledge in the CBRs (Richardson, Citation2017).

Finally, both case studies – Cali-Baja and Cascadia – may play a role in the pursuit of global innovation. They can be considered gateways to access external markets, larger and talented workforce, and financial capital resources.

As the first if its kind, the innovative methodology opens up new research avenues: (1) considering cross-border innovation from different industry levels/sector perspectives; and (2) integrating the CBRIS model with those findings. More accurate methods (e.g., social network analysis) should shed a light on organizational and social proximities. An in-depth study of the hindrances and drivers might complement this research.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Francesco Cappellano http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3061-433X

Annalisa Rizzo http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5070-6851

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The new United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) was signed on 30 November 2018 in the renegotiation of NAFTA.

REFERENCES

- Balland, P., Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2015). Proximity and innovation: From statics to dynamics. Regional Studies, 49(6), 907–920. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2014.883598

- Blatter, J. (2004). From ‘spaces of place’ to ‘spaces of flows’? Territorial and functional governance in cross-border regions in Europe and North America. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(3), 530–548. doi: 10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00534.x

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. doi: 10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Cappellano, F., & Makkonen, T. (2019). Cross-border regional innovation ecosystems: The role of non-profit organizations in cross-border cooperation at the US–Mexico border. GeoJournal.

- Ganster, P., & Collins, K. (2017). Binational cooperation and twinning: A view from the US–Mexican border, San Diego, California, and Tijuana, Baja California. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 32(4), 497–511. doi: 10.1080/08865655.2016.1198582

- Granovetter, M. (1973). The Strength of Weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360–1380. doi: 10.1086/225469

- Herzog, L., & Sohn, C. (2014). The cross-border metropolis in a global age: A conceptual model and empirical evidence from the US–Mexico and European border regions. Global Society, 28(4), 441–461. doi: 10.1080/13600826.2014.948539

- Hudec, O., & Urbancikova, N. (2010). Regional Innovation Strategies in a Cross-border Environment. Jönköping, Sweden: European Regional Science Association (ERSA).

- Lazzeretti, L., & Capone, F. (2016). How proximity matters in innovation networks dynamics along the cluster evolution. A study of the high technology applied to cultural goods. Journal of Business Research, 69, 5855–5865. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.04.068

- Lundquist, K., & Trippl, M. (2013). Distance, proximity and types of cross-border innovation system: A conceptual analysis. Regional Studies, 47(3), 450–460. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2011.560933

- Lundvall, B. A. (1992). National innovation system: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. London: Pinter.

- Makkonen, T., & Williams, A. M. (2018). Developing survey metrics for analysing cross-border proximity. Geografisk Tidsskrift/Danish Journal of Geography, 118(1), 114–121. doi: 10.1080/00167223.2017.1405734

- Muller, E., et al. (2017). Smart specialisation strategies and cross-border integration of regional innovation systems: Policy dynamics and challenges for the Upper Rhine. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(4), 684–702.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2013). Regions and innovation: Collaborating across borders. Paris: OECD.

- Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe: Significance and drivers of regional cross-border co-operation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153–171. doi: 10.1177/0969776403010002004

- Richardson, K. E. (2017). Knowledge borders: Temporary labor mobility and the Canada–US border region. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Trippl, M. (2010). Developing cross-border regional innovation systems: Key factors and challenges. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 101(2), 150–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9663.2009.00522.x

- Vance, A. (2012). Crossing bridges: Observations and strategies by cross-border business communities in an evolving regulatory environment. Bellingham, WA: Border Policy Research Institute Publications.

- van den Broek, J., & Smulders, H. (2015). Institutional hindrances in cross-border regional innovation systems. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 116–122. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2015.1007158