ABSTRACT

Global-city research has focused primarily on considering transnational corporations and transnational professionals (TNPs) in economic terms, neglecting the role of TNPs’ specific socio-spatial practices in constituting the transnational space. Although researchers on global city-regions (GCRs) have pointed to the relevance of the larger regions for global cities, little is known about the TNPs moving into such regions, and their socio-spatial patterns within them. On the basis of novel empirical results derived from 45 in-depth interviews with TNPs, this paper sheds a light on patterns of socio-spatial practices in Tokyo, Japan – a well-established, yet unexplored, global city – and its larger GCR. Results show two distinct patterns within the TNPs, that is, the gaijin ghetto and the Pro-Tokyoite patterns. The gaijin ghetto is characterized by a Western-dominated culture and is spatially concentrated within a very small area in the core of Tokyo, with limited extra-urban spots in the GCR. The Pro-Tokyoite pattern is spatially more varied and spread within the larger metropolitan area, reaching into the wider GCR, with social practices and interactions closer to the local peer group. This paper discusses how these socio-spatial patterns are embedded in the global, regional and local spatial settings and it demonstrates that TNPs are in fact venturing out of the city centre into the broader GCR.

INTRODUCTION

Although transnational corporate professionals have been widely discussed in the context of global cities, the focus has been limited to economic spaces and social connections in the form of their business communities. Some recent regional and economic–geographical studies focus on the spatial effects of globalization on global city-regions (GCRs), but they primarily consider corporate real estate development as a spatial phenomenon, with transnational corporations (TNCs) being the main economic actors of globalization. Such studies do not consider transnational corporate professionals (TNPs) as actors in the urban and regional economy, involved in the housing market and everyday social practices embedded in the urban and regional spaces. Beyond professional activities, such socio-spatial practices encompass social events and leisure activities and residential choices, contributing to specific transnational spaces within the GCR. As TNPs’ social practices are not strictly limited to the inner core city centre of global cities (such as Tokyo studied here) but also exist beyond the city limits, the research question that arises is: How do patterns of social practices of transnational professionals in spatial settings, that is, socio-spatial practices, constitute the transnational space in the GCR?

NEW REGIONALISM OF GLOBAL CITY-REGIONS

The GCR signifies the spatial phenomenon of ‘distinctive subnational (i.e., regional) social formations whose local character and dynamics are undergoing major transformations due to the impacts of globalization’ (Scott, Citation2011, p. 1; original emphasis). These regions have become increasingly independent from national states and subject to events happening on the global level, a phenomenon discussed as the new regionalism in regional studies (Hoyler, Parnreiter, & Watson, Citation2018). The GCR as an analytical unit has been a special interest amongst urban and regional scientists (e.g., Hall, Citation2011; Neuman & Hull, Citation2009).

When it comes to the spatial dynamics induced by the increasing globalization in these GCRs, however, research concentrates on the corporate context and analysis of the spatial impact of global-city-making focuses on corporate real estate (e.g., Lizieri & Pain, Citation2014; Parnreiter, Citation2009). Research related to TNPs usually focuses on their roles in corporate strategies and business communities (e.g., Beaverstock, Citation2004; Morgan, Citation2001), largely ignoring the impact they may have through their social practices beyond corporate functions and city limits.

Despite different understandings of the region in GCR research, one commonality is that the region and its borders are defined by functional rather than administrative context. While Scott (Citation2011) refers to the transformations on a subnational scale, the core idea of the GCR derives from economic–geographical and regional development contexts, in which industries and firms locate in the broader region surrounding the global city. Whereas the global city is believed to induce social polarization through the concentration of industries around finance, insurance and real estate (FIRE sector) and their professionals (Sassen, Citation1991), the GCR is characterized as accommodating the social middle class and different economic sectors. The GCR is thus useful in analysing ‘a more even distribution of economic benefits under globalization’ (Sassen, Citation2011, p. 80), alluding to the integration of societal aspects into the debate on GCRs (cf. Fainstein, Citation2011).

Scott, Agnew, Soja, and Storper (Citation2011) identify social geography as one of the key agendas in the GCR debate, touching upon issues of migration and ‘increased cultural and demographic heterogeneity’ (p. 18). However, it is impossible to find empirical material on exactly how and what is occurring, especially on the subregional level. Cases dealing with the global city-regional transformation thus become eclectic patchworks of diverse case studies, for example, the description of polycentric city-region elements identified by Hall (Citation2011). In fact, defining the GCR by its functional borders – particularly its ‘internal linkages’ (p. 72) – is empirically problematic as statistics are principally collected in administrative units.

METHODOLOGY FOR CAPTURING TRANSNATIONAL SOCIO-SPATIAL PATTERNS IN TOKYO

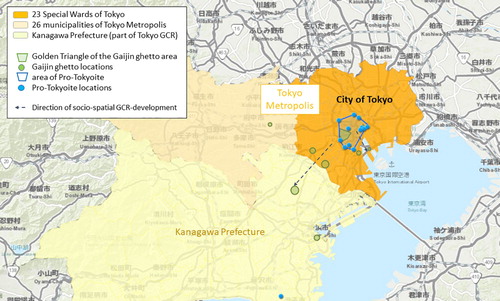

The metropolitan region of Tokyo stretches over an area of 14,000 km2; Tokyo City itself encompasses 23 special wards located within the Tokyo Metropolis, which additionally covers further municipalities. The GCR, according to its functional characteristics, stretches both beyond the city borders to the outskirts of Tokyo Metropolis and beyond these borders into adjacent prefectures, including Kanagawa ().

As a consequence of the cross-bordering nature of GCRs as well as the limited availability of socio-spatial data on migrants beyond income distribution or labour market data, a more explorative qualitative approach appears appropriate. This study is based on qualitative data, specifically problem-oriented interviews with 45 transnational professionals (TNPs) of the financial industry in Tokyo with the research problem focused on their socio-spatial patterns and preferences within the GCR.Footnote1 The interviewees were selected against several criteria reflecting the transnationality in their mobility and professional patterns: (1) a higher managerial position within a TNC (to be decision-makers in their companies, thus being part of the global city-makers); (2) extensive experience abroad for long- and/or short-term assignments overseas; and for the case study (3) work and residential experience in the GC Tokyo. Owing to the importance of the FIRE sector in the context of GCR-making and bearing in mind the transnational corporate structure as the GCR context, (4) the TNPs were selected from the financial industry. This focus is reasonable as the emergence and development of global cities is attributed to the globalizing FIRE sector. It also allows intra-group comparisons of patterns, as variables are kept constant. Regarding the participants’ ethnic or migrant background, (5) membership of the transnational corporate community and a mobile background were taken as the key reference for the transnational social group. This approach addresses the much discussed and criticized ethno-focal lens in transnational migration research. The nationalities and ethnicities of the interviewees were diverse, covering American, British (including Scottish and English), Australian, German, Japanese, Indian, Singaporean, French, Italian, Korean, Chinese-Singaporean and Slovak backgrounds. Interviewees were chosen according to their professional profiles as transnational actors in TNCs and the global economy rather than by their residential locations. However, most of the TNPs resided in the Minato and adjacent wards, which are characterized by higher shares of high-income residents. As the access to such high-profile and specific TNPs is very limited and difficult, the recruitment of interviewees was realized by using personal contacts to gatekeepers and the successive snowballing technique common in such cases.

Furthermore, to embed the accounts of TNPs into a larger perspective better, five expert interviews with major real estate agencies specializing in housing rentals for corporate professionals and city officials of Minato ward were conducted. This was further complemented by focus group interviews with local peers who were born Tokyoites with a high education and income levels who lived in the centre of the city. The topics discussed encompassed their own socio-spatial behaviours and environments, as well as reflections on different parts of the city. This triangulation contributed to reducing the biases of TNPs’ accounts of their own socio-spatial practices.

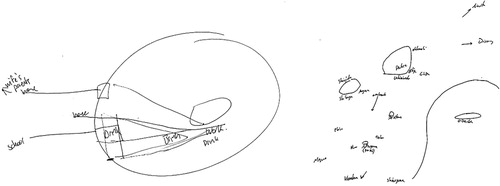

The study innovated by complementing the interviews with mental maps (Gould & White, Citation1974; Lynch, Citation1960) to capture better the socio-spatial impact within and beyond the city of Tokyo. TNPs were explicitly asked for an ego-centric map of Tokyo, in which they drew in places of special interest both professionally and personally. Based on the premise that maps drawn by individuals reflect the knowledge as well as the personal experience of the environment, the TNPs reproduced their socio-spatial patterns and indicated the geographical extent of their daily lives in the larger Tokyo region. These mental maps were then cumulatively analysed for intra-group differences and specificities. They were then transferred into a geographical map encompassing the mentioned and drawn areas of special importance within the GCR Tokyo, as well as any figurative socio-spatial structures collectively perceived as existent in their own group behaviour.

TRANSNATIONAL PROFESSIONAL PATTERNS: GAIJIN GHETTO VERSUS PRO-TOKYOITE

Two distinct ideal-type patterns of socio-spatial practices among the TNPs, namely the gaijin ghettoFootnote2 and the Pro-Tokyoites, are identified. All TNPs are strongly embedded in the corporate context in that their socio-spatial patterns regarding professional and semi-formal encounters and activities are naturally located near the central business district (CBD) and other TNC office locations. Although the interviewees have the economic capital to choose their residential locations, their choice is heavily impacted by global corporate strategies and also dependent on the regional supply-side of real estate agencies. As TNCs have shifted from trips for the TNPs to search for housing to more cost-efficient commissioning of relocation and real estate agencies, the TNPs – who often experience linguistic barriers and lack of local social networks – fully depend on the housing offer preselected by these companies in specific residential areas (sometimes even against their actual preferences). It is only after time that the socio-spatial patterns diversify beyond their corporate context and begin to change. Juxtaposing exemplary mental maps () already shows the distinction between the two patterns: the gaijin ghetto is spatially limited and the Pro-Tokyoite more dispersed.

Basing on the 45 interviews with the TNPs, the two patterns became even more visible when transferred to a geographical map (). The gaijin ghetto type would be commonly known as the ‘expats’ area, which is characterized by English-language services and imported Western products. TNPs with this pattern socialize almost exclusively in their social networks of international migrants. They show a spatial concentration within a rather small triangular area within the core of the global city Tokyo (named the ‘Golden Triangle’) with limited extra-urban spots or exclaves in the outskirts of Tokyo, closer to international schools and with large single-family detached housing.

Figure 2. Socio-spatial patterns of transnational professionals in the Tokyo global city-region (GCR).

The Pro-Tokyoites overlap with the gaijin ghetto as private relations often build on professional networks and other semi-formal encounters with other TNPs. However, Pro-Tokyoites venture further out to areas that are ‘too Japanese’ for gaijin ghetto professionals, reflecting the (perceived) non-Western and more local culture and people in these areas; the Pro-Tokyoite areas are more varied and dispersed, yet centralized around the CBD and the city centre. The spatial spread of these Pro-Tokyoites within the larger metropolitan area goes hand in hand with their social interactions with local peers. In such cases, the spaces encompass not just exclaves as in case of the gaijin ghetto, but also activities in the wider GCR, as in Western parts of neighbouring Kanagawa.

One exceptional case worth mentioning is the downgrading of a gaijin ghetto pattern out to the GCR. During the recent global financial crisis, one TNP had to change to a local contract with less income and fewer of the benefits usually available on expatriate contracts. They were concerned about maintaining the gaijin ghetto's high living standards (housing, education). The TNP planned to relocate out from the central gaijin ghetto to what Hall (Citation2011, p. 74) characterized as the ‘internal edge city’ of Shinjunku in the furthest Western part of the city of Tokyo.

DISCUSSION: SOCIO-SPATIAL VENTURING OUT TO THE TOKYO GCR

The findings show the connections of the socio-spatial practices of TNPs to the GCR and that the identified types are impacted by different dynamics. Whereas Pro-Tokyoites’ involvement in the GCR is mainly based on individual ‘ways of daily life’, the dynamism of the gaijin ghetto is a case of a stronger, structurally embedded, context of the economic and political decisions of policy-makers and global economic actors on different scales.

Although more prone to venture out of the limited transnational space of the gaijin ghetto within Tokyo, Pro-Tokyoites actually remain based in the core global city with only private and recreational sojourns to outskirts of the metropolitan region. Pro-Tokyoites follow the patterns of local indigenous TNC colleagues and other upper-class Tokyoites, although the overlap with the gaijin ghetto appears to be specific to these TNPs and is observed less with local peers. The GCR in that sense is somewhat affected by the change in the customer-base for gastronomy and leisure activities, yet as the sojourns are temporary and do not entail long-term integration in these regions – and more importantly as these TNPs primarily and specifically demand the non-English environment – the extent of social and cultural transformation in these regions is limited compared to the gaijin ghettos.

The gaijin ghetto TNPs appear to be spatially limited and less mobile. They are most connected to the expansion of the transnational space beyond the city borders into the GCR. The preselection of residential locations by relocation and real estate agencies that TNCs use is concentrated in gaijin ghettos, which in turn are often part of urban development projects located in newly developed traditionally non-prestigious areas within the city and further out of the core city. These socio-spatial choices of the gaijin ghetto TNPs, compared to the Pro-Tokyoites choosing more affluent areas of Tokyo, provide the urban and regional economy with opportunities to develop new highly desirable areas. Tokyo's boundaries have been dynamically shifting over the decades and centuries, both to adjacent regions and to unbuilt spaces on the water. With the influential lead of relocation and real estate agencies, the urban centrality has shifted from the traditional CBD to other locations within the wider region. The newest trend is the large-scale development of the Tokyo Bay area for special economic zones and sports events (The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games, Citationn.d.; Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Citationn.d.), which prospectively provide locations for further gaijin ghettos. The expansion of the gaijin ghetto in the GCR is embedded in the larger context of regional development strategies where private urban development projects are supported by the metropolitan government. The dynamics surrounding the gaijin ghetto areas are expanding the functional boundaries into the GCR, involving further regional and national actors beyond the city itself. The development of special economic zones for global corporations within the GCR Tokyo are part of national strategies to improve the economic performance of the country. The metropolitan government of Tokyo as well as prefectural bodies in the GCR support and align with these global and national trends, collaborating with governmental entities to attract global talents and companies, but also locally subsidize real estate projects. Such urban development projects are driven by private investors and large TNCs. Subnational, that is, meso-level, actors of metropolitan and prefectural governments and also actors in the regional economy – such as private investors, private real estate developers and the otherwise global city-centred TNCs and their TNPs as actors – contribute to a highly interwoven system of space-making in the GCR.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presents new evidence on the production of transnational spaces, crossing not only national but also city borders in Tokyo, through the socio-spatial behaviour of transnational migrants. It contributes to the debates on GCR in three ways. First, it brings empirical evidence from unique qualitative research, contributing to further discussions on the GCR on empirical grounds. Second, basing on these findings, it sheds a light on the ‘patterns of social stratification, intra-metropolitan income distribution and demographics, and ways of daily life’ which are substantially marked by the ‘forces shaping the emergence of global city-regions’ (Scott et al., Citation2011, p. 18). Third, it elucidates the ‘ways of daily life’ aspect, that is, social-spatial mobility and practices (partly also socio-economic mobility) of those TNPs, who have previously been assumed to be restricted to the urban core.

TNPs are the connecting link between the global financial economy of TNCs with their corporate strategies, in which TNPs are embedded, and the regional space, which TNPs inhabit and live in with their particular socio-spatial practices as individuals. The transnational spaces produced by these actors are more subtle than the otherwise expected ‘global flows’. They are locally bound, yet going beyond the urban contexts and venturing out to the broader GCR. Understanding the nexus between the global and global city-regional space contributes to a better understanding of the spatial transformations induced by global actors in the regions (cf. Solheim, Citation2016).

The increasing mobility and growing number of TNPs, who are not only economic actors as part of TNCs but also interact and are involved in local daily lives, calls for a shift in perspective regarding these migrants. While lower skilled and permanent migrants have frequently been the focus of transnational migration research, as well as for local policy-makers dealing with integration and housing issues, TNPs have been somewhat neglected. However, with their specific socio-spatial patterns that reach beyond the CBD, where they normally work, questions arise regarding accommodation of their needs and patterns. With socio-spatial transformation occurring in the GCR, economic services and markets also need to adapt to the population venturing out of the city centre. This then also implies that local and regional policy-makers are required to consider support networks to accommodate this development, be it to help local entrepreneurs or other ethnic minority entrepreneurs addressing the demands of the TNP residents. Moreover, as these migrants move beyond administrative city borders, the reactive measures also require better coordination of the governmental bodies at different levels. Furthermore, specificities of socio-spatial practices that are connected to urban development projects also come hand in hand with frictions with the residential population, with issues of, for example, gentrification and displacements.

Taking the actor-based approach to studying TNPs and their transnational spaces contributes to a better understanding and substantiation of the claim of vulnerability of the residents (cf. Fainstein, Citation2011, p. 295), which is a highly relevant finding for urban and regional policy-makers and practitioners. Understanding socio-spatial patterns of migrants allows policy-makers to tackle issues of urban segregation and social integration more precisely. Measures to accommodate the social diversification encompass not only providing multilinguality in transportation and physical infrastructure but also supporting foreign residents in administrative procedures and finding anchors in local society. Supporting migrants as well as local entrepreneurship is also part of the regional economy which can be better implemented if the needs and practices of the migrant population are known. What remains for further investigation is the impact of these transnational socio-spatial patterns on the local and regional economy, for example, real estate development and changes in economic flows, which requires secondary data and insights into the perspectives of the different regional actors involved.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Sakura Yamamura http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3820-8574

Notes

1 Interviews were carried out in English or, upon request from the interviewee, in Japanese or German, between 2011 and 2014. They were carried out either face to face (in the interviewee’s office space or another location, usually close to their work environment) or by phone, depending on the availability of the TNPs. Interviewees were recorded and transcribed, and post-interview field notes were made; for the analysis, the interviews were selectively coded in accordance with Mayring's (Citation1994) approach of qualitative content analysis using MaxQDA.

2 Self-designation, whereas gaijin is a slightly pejorative term for a foreigner and the usage of ghetto for their upper class residential areas, is meant ironically.

REFERENCES

- Beaverstock, J. V. (2004). ‘Managing across borders’: Knowledge management and expatriation in professional service legal firms. Journal of Economic Geography, 4, 157–179. doi: 10.1093/jeg/4.2.157

- Fainstein, S. S. (2011). Inequality in global city-regions. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 285–298). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gould, P., & White, R. (1974). Mental maps. New York: Penguin.

- Hall, P. A. (2011). Global city-regions in the twenty-first century. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 59–77). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hoyler, M., Parnreiter, C., & Watson, A. (2018). Global city makers: Economic actors and practices in the world city network. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Lizieri, C., & Pain, K. (2014). International office Investment in global cities: The production of financial space and systemic risk. Regional Studies, 48, 439–455. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.753434

- Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Mayring, P. (1994). Qualitative inhaltsanalyse. Konstanz: UVK Univ.-Verl. Konstanz.

- Morgan, G. (2001). Transnational communities and business systems. Global Networks, 1, 113–130. doi: 10.1111/1471-0374.00008

- Neuman, M., & Hull, A. (2009). The futures of the city region. Regional Studies, 43, 777–787. doi: 10.1080/00343400903037511

- Parnreiter, C. (2009). Global-city-formation, Immobilienwirtschaft und Transnationalisierung. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 53, 138–155.

- Sassen, S. (1991). The global city: New York, London, Tokyo, Princeton. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sassen, S. (2011). Global cities and global city-regions: A comparison. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 78–95). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A. J. (2011). Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Scott, A. J., Agnew, J., Soja, E. W., & Storper, M. (2011). Global city-regions. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy (pp. 11–32). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Solheim, M. W. C. (2016). Foreign workers and international partners as channels to international markets in core, intermediate and peripheral regions. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 491–505. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2016.1258324

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. (n.d.). Tokyo leading the world in business. Retrieved from https://www.seisakukikaku.metro.tokyo.jp/invest_tokyo/assets/pdf/en/invest-tokyo/conference/leaflet_en.pdf

- The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. (n.d.). Olympic Venues: Heritage Zone & Tokyo Baz Zone. Retrieved from https://tokyo2020.org/en/games/venue/olympic/