ABSTRACT

The entrepreneurial ecosystems literature lists numerous factors, emphasizing their interactions. However, there is limited empirical literature exploring the causal mechanisms, nor an understanding of the relative importance of these factors. This paper places the entrepreneur at the centre of the analysis by constructing a career history network of over 2100 Irish high-tech entrepreneurs. It finds that prior employment experience can be used to measure the prominence of different actors anticipated in the entrepreneurial ecosystem literature. Regional universities play an anchor role within each regional entrepreneurial ecosystem. Universities are indirectly connected to other organizations to form an integrated network that supports high-tech entrepreneurship. This approach may be used to assess and motivate interventions to support integration and anchor organization establishment that enhances regional entrepreneurial activity.

INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) emphasize the interactions between factors and places the entrepreneur, especially high-growth firms (Nicotra, Romano, Del Giudice, & Schillaci, Citation2018; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018), in a central role for regional development (Malecki, Citation2018). However, there is limited systemic empirical analysis of factors (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Nicotra et al., Citation2018) or their relative importance (Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018). Further, the EE literature highlights the causal ambiguity between factors and entrepreneurship (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Stam, Citation2015; Stam & Spigel, Citation2017).

To investigate the relative importance of EE factors, this paper places the individual entrepreneur in a central role by analysing prior employment of over 2100 high-tech founders in Ireland. It does so by reviewing factors listed in the EE literature, followed by constructing a career history network of organizations. This allows for the analysis of the relative importance of different categories of organizations within EEs.

LITERATURE REVIEW

EE actors include entrepreneurs, universities, investors, large incumbent firms, incubators and accelerators (Brown & Mason, Citation2017), supported by factors including knowledge and human capital (Qian, Acs, & Stough, Citation2013), culture (Isenberg, Citation2010; Spigel, Citation2017), institutions and governance (Acs, Estrin, Mickiewicz, & Szerb, Citation2018; Colombo, Dagnino, Lehmann, & Salmador, Citation2019; Herrmann, Citation2019), physical infrastructure (Neck, Meyer, Cohen, & Corbett, Citation2004), and social capital and networks (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Neck et al., Citation2004).

Critiques of the EE approach highlight long lists that lack causal clarity (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017; Nicotra et al., Citation2018; Stam, Citation2015) although Nicotra et al. (Citation2018) offer some parsimony by discussing the mechanisms by which actors in the EE impact financial, institutional, social and knowledge capital.

For knowledge capital, a central role for entrepreneurial universities is acknowledged (Miller & Acs, Citation2017). Universities connect to the economy through education, firm consultation, technology transfer (Etzkowitz, Citation2013), university spinouts (Lockett, Wright, & Franklin, Citation2003; Vohora, Wright, & Lockett, Citation2004), facilitating local linkages (Bramwell & Wolfe, Citation2008; Etzkowitz, Citation2013), and serving as institutional anchors for regional development (Harris & Holley, Citation2016). Although the appropriate scale and boundaries at which to measure EEs remains unclear (Colombo et al., Citation2019; Malecki, Citation2018; Stam, Citation2015), the university is considered by Miller and Acs (Citation2017) as the appropriate unit of analysis for EEs in the United States. Nonetheless, the EE literature (Malecki, Citation2018; Nicotra et al., Citation2018; Spigel & Harrison, Citation2018) argues that students are the main entrepreneurial actors for university spinouts (Hayter, Lubynsky, & Maroulis, Citation2017), and university spinouts comprise a small proportion high-growth firms (Wennberg, Wiklund, & Wright, Citation2011), knowledge capital accumulation is driven primarily through education.

However, prior employment develops the tacit knowledge required for entrepreneurial firms (Burton, Sørensen, & Beckman, Citation2002) and experience can be transferred from one setting to another (Delmar & Shane, Citation2006). The majority of entrepreneurs have prior experience (Robinson & Sexton, Citation1994), which can come from sources other than universities. Multinational enterprises have been proposed as anchors for the EE (Bhawe & Zahra, Citation2019), producing corporate spinoffs (Klepper, Citation2001; Klepper & Sleeper, Citation2005; Neck et al., Citation2004), which make up a larger proportion of start-ups than university spinouts, especially in knowledge-intensive industries (Wennberg et al., Citation2011). Industry employment experience also enhances new venture performance (Delmar & Shane, Citation2006), although knowledge spillovers from incumbents are not guaranteed because incumbents may curtail investment if it leads to increased competition or a diffusion of core capabilities through corporate spinoffs (Colombo & Dawid, Citation2016).

Venture capital firms, incubators and accelerators also enhance EEs by injecting capabilities and professionalizing management teams (Clarysse, Wright, & Van Hove, Citation2015; Cumming, Werth, & Zhang, Citation2019; Meglio, Destri, & Capasso, Citation2017), and because tacit knowledge required to grow a firm cannot easily be obtained indirectly (Carroll & Mosakowski, Citation1987), prior experience in start-up firms is an important driver of knowledge capital.

METHODOLOGY

The career histories of 2148 founders of 1503 Irish indigenous high-tech firms, identified from an Irish technology directory, were obtained from public sources. Prior employers of the entrepreneurs were categorized by matching against the directory’s lists of indigenous and multinational tech firms, investors and ‘hubs’. Hubs consist of research institutes and accelerators. Further categorization used the Higher Education Authority list of 22 Irish higher education institutes (HEIs). Indigenous high-tech firms were further categorized as university spinouts using a listing of 329 Irish university spinouts. All other prior employers are categorized as ‘Other’.

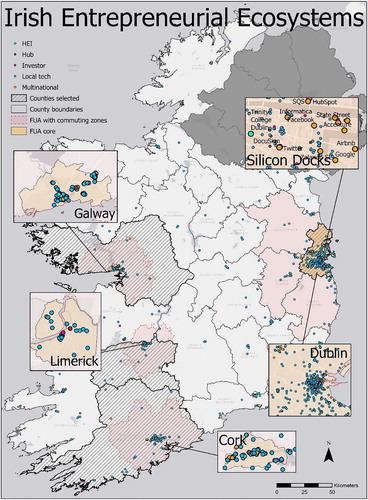

First, the breadth of prior employers is explored by comparing the number of employers in the career networks against the number in the appropriate directory lists. Second, social network analysis, proposed as an analytical approach to EEs (Alvedalen & Boschma, Citation2017), is employed to determine the relative prominence of organizations based on the number of connections of each organization (Burton et al., Citation2002). Network level statistics are achieved by transforming two-mode networks of founders and organizations into a one-mode network of interacting organizations. Third, the relative prominence of organization types was analysed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) of the mean number of degrees of each category of organization to which each indigenous tech firm is connected. Fourth, regional levels of analysis are contrasted for four Irish counties (). Administrative counties were chosen as the regional boundary because functional urban areas (FUAs) differ in size and, in the case of Dublin, include unconnected EEs such as Maynooth, Drogheda and Wicklow (). Future work may consider scales such as the information technology district known as ‘Silicon Docks’. Finally, network statistics of each region are analysed to understand the overall regional structure of each EE.

RESULTS

Prior employment of indigenous high-tech founders was concentrated on a minority of identified multinational tech firms, investment organizations and hubs (). For example, only 133 of the 354 multinationals (38%) had employed an indigenous high-tech founder. In contrast, prior employment in HEIs was diversified across all 22 identified HEIs (100%).

Table 1. Summary of data.

A total of 7.32% of indigenous firms are identified as university spinouts (). In contrast, 15.54% of entrepreneurs listed prior employment experience in one of the 22 HEIs. Of the 334 entrepreneurs with prior HEI experience, 134 (6.24%) firms were founded within a year of leaving HEI employment, approximately in line with the proportion of university spinoffs. The remaining 200 either continued in HEI employment or left HEI employment more than three years before firm foundation.

Table 2. Proportion of university spinouts and higher education institute (HEI) employment experience.

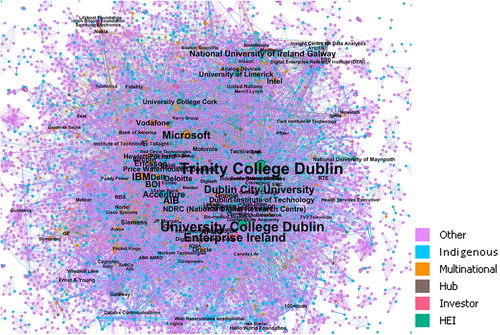

Despite the small proportion of university spinouts, shows that Trinity College Dublin, University College Dublin and Dublin City University are most prominent, followed by multinational tech firms IBM and Microsoft. This is shown by the size of the nodes and labels that reflects their number of connections within the network.

shows that there are significant differences, at a confidence level of 95%, between the mean degrees of EE organization types. All EE actors have greater prominence than ‘Other’ organizations, and HEIs are the most connected organization type.

Table 3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) of national average degrees of connected resources.

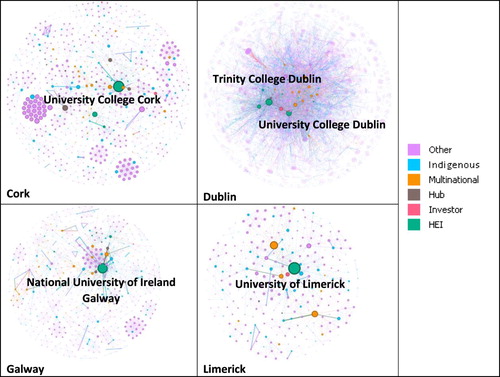

shows that regional networks identify regional HEIs as the most prominent organizations in each region.

shows that in all regions, the average degrees of organization types connected to indigenous tech firms are greater than ‘Other’ organizations, with the exception of investors in Galway and hubs in Limerick.

Table 4. Regional mean degrees of organization types.

An average path length of approximately four for each region () means that organizations average three degrees of indirect connections to other organizations for each direct connection. The number of neighbours between six and nine shows that there are a large number of paths for indirect connections.

Table 5. National network structure.

DISCUSSION

Investment organizations, accelerators, incubators, research institutes, universities and multinational tech firms are all more connected to high-tech founders than ‘Other’ prior employers, which highlights a technique policy might employ to measure EEs in terms of the prominence of different regional actors.

In the Irish institutional and cultural context, universities play an important anchor role in supporting the knowledge capital required by entrepreneurs. This despite only 7% forming university spinouts and only 16% of entrepreneurs having HEI employment experience. For measurement of entrepreneurial university performance, HEI employment experience of founders captures additional impacts by universities beyond university spinout numbers.

The average path lengths of career networks suggests that indirect connections exist. Although universities have been proposed as key actors in EEs for their role in education (Malecki, Citation2018), their connectedness highlights the importance of their role. They directly create spinoffs that are embedded in a wider EE, and indirectly connect through employment at another organization within the network. These connections provide a conduit through which capabilities can be transferred. Policy can now measure this additional avenue of knowledge spillover to regional entrepreneurship through earlier employment experience.

The analysis also addresses uncertainty about the level at which EEs should be studied (Malecki, Citation2018) by showing regional networks with results consistent with that of the national network., although since institutional and cultural contexts vary at a national level (Acs, Autio, & Szerb, Citation2014; Herrmann, Citation2019) further work is needed to analyse prior experience in EEs across these dimensions.

In the two smaller regions, Galway and Limerick, investors and hubs show less prominence than ‘Other’ organizations. This echoes Malecki’s (Citation2018) observation that all EEs, especially small ecosystems, will be deficient in some ways. In areas with low levels of regional entrepreneurship, policy can identify deficiencies in across categories that may inform interventions to create linkages that draw on knowledge found in organizations external to the region, as well as inform priorities in terms of foreign direct investment attraction and public institutional investment.

CONCLUSIONS

Knowledge capital is an important component of the EE (Nicotra et al., Citation2018) and prior employment experience of high-tech entrepreneurs is an important mechanism for knowledge accumulation from a range of organizations identified in the EE literature. This study provides empirical support to draw in important streams of university spinout and corporate spinoff literature into the EE approach. Doing so provides a holistic causal mechanism that may inform policy interventions that seek to support regional entrepreneurship. Policy can use this to better motivate the benefits of attracting and establishing regional employers that gestate a foundation of knowledge capital for future entrepreneurship.

This study provides empirical support for the EE actors previously supported mainly by authors’ experience (Nicotra et al., Citation2018). It also supports Alvedalen and Boschma’s (Citation2017) view that social network analysis can provide an empirical approach to analyse interactions in the EE. Further analysis using this approach may reveal additional prominent categories of organizations within the EE that have thus far not been identified through prior authors’ experience, as well as investigate the impact of different institutional and cultural contexts on the relative importance of prior experience from different EE actors.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Kevin Walsh http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9405-1623

REFERENCES

- Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494.

- Acs, Z. J., Estrin, S., Mickiewicz, T., & Szerb, L. (2018). Entrepreneurship, institutional economics, and economic growth: An ecosystem perspective. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 501–514.

- Alvedalen, J., & Boschma, R. (2017). A critical review of entrepreneurial ecosystems research: Towards a future research agenda. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 887–903.

- Bhawe, N., & Zahra, S. A. (2019). Inducing heterogeneity in local entrepreneurial ecosystems: The role of MNEs. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 437–454.

- Bramwell, A., & Wolfe, D. A. (2008). Universities and regional economic development: The entrepreneurial University of Waterloo. Research Policy, 37(8), 1175–1187.

- Brown, R., & Mason, C. (2017). Looking inside the spiky bits: A critical review and conceptualisation of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 11–30.

- Burton, M. D., Sørensen, J. B., & Beckman, C. M. (2002). Coming from good stock: Career histories and new venture formation. In M. Lounsbury, & M. Ventresca (Eds.), Social structure and organizations revisited (pp. 229–262). Bingley: Emerald Group.

- Carroll, G. R., & Mosakowski, E. (1987). The career dynamics of self-employment. Administrative Science Quarterly, 32(4), 570–589.

- Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van Hove, J. (2015). A look inside accelerators. London: Nesta.

- Colombo, M. G., Dagnino, G. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Salmador, M. (2019). The governance of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 419–428.

- Colombo, L., & Dawid, H. (2016). Complementary assets, start-ups and incentives to innovate. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 44, 177–190.

- Cumming, D., Werth, J. C., & Zhang, Y. L. (2019). Governance in entrepreneurial ecosystems: Venture capitalists vs. Technology parks. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 455–484.

- Delmar, F., & Shane, S. (2006). Does experience matter? The effect of founding team experience on the survival and sales of newly founded ventures. Strategic Organization, 4(3), 215–247.

- Etzkowitz, H. (2013). Anatomy of the entrepreneurial university. Social Science Information sur les Sciences Sociales, 52(3), 486–511.

- Harris, M., & Holley, K. (2016). Universities as anchor institutions: Economic and social potential for urban development. In M. B. Paulsen (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research, Vol 31 higher education-handbook of theory and research (pp. 391–437). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Hayter, C. S., Lubynsky, R., & Maroulis, S. (2017). Who is the academic entrepreneur? The role of graduate students in the development of university spinoffs. Journal of Technology Transfer, 42(6), 1237–1254.

- Herrmann, A. M. (2019). A plea for varieties of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 52(2), 331–343.

- Isenberg, D. (2010). How to start an entrepreneurial revolution. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 40–50.

- Klepper, S. (2001). Employee startups in high-tech industries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 10(3), 639–674.

- Klepper, S., & Sleeper, S. (2005). Entry by spinoffs. Management Science, 51(8), 1291–1306.

- Lockett, A., Wright, M., & Franklin, S. (2003). Technology transfer and universities’ spin-out strategies. Small Business Economics, 20(2), 185–200.

- Malecki, E. J. (2018). Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geography Compass, 12(3), 21.

- Meglio, O., Destri, A. M. L., & Capasso, A. (2017). Fostering dynamic growth in new ventures through venture capital: Conceptualizing Venture capital Capabilities. Long Range Planning, 50(4), 518–530.

- Miller, D. J., & Acs, Z. J. (2017). The campus as entrepreneurial ecosystem: The University of Chicago. Small Business Economics, 49(1), 75–95.

- Neck, H. M., Meyer, G. D., Cohen, B., & Corbett, A. C. (2004). An entrepreneurial system view of new venture creation. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(2), 190–208.

- Nicotra, M., Romano, M., Del Giudice, M., & Schillaci, C. E. (2018). The causal relation between entrepreneurial ecosystem and productive entrepreneurship: A measurement framework. Journal of Technology Transfer, 43(3), 640–673.

- Qian, H. F., Acs, Z. J., & Stough, R. R. (2013). Regional systems of entrepreneurship: The nexus of human capital, knowledge and new firm formation. Journal of Economic Geography, 13(4), 559–587.

- Robinson, P. B., & Sexton, E. A. (1994). The effect of education and experience on self-employment success. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(2), 141–156.

- Spigel, B. (2017). The relational organization of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 49–72.

- Spigel, B., & Harrison, R. (2018). Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 151–168.

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769.

- Stam, E., & Spigel, B. (2017). Entrepreneurial ecosystems. In R. Blackburn, D. De Clercq, J. Heinonen, & Z. Wang (Eds.), The SAGE handbook for small business and entrepreneurship (pp. 407–422). London: SAGE.

- Vohora, A., Wright, M., & Lockett, A. (2004). Critical junctures in the development of university high-tech spinout companies. Research Policy, 33(1), 147–175.

- Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., & Wright, M. (2011). The effectiveness of university knowledge spillovers: Performance differences between university spinoffs and corporate spinoffs. Research Policy, 40(8), 1128–1143.