ABSTRACT

This paper explores the potentials and limits of using European structural and investment (ESI) funds for rural development in one of the least developed areas of Central and Eastern Europe: Romania’s Sălaj county. The research draws on peripheralization as a key theoretical concept and on frame analysis as a heuristic framework for understanding the effects of policy instruments on development capacities in peripheral places. Desk research and semi-structured interviews reveal how local leaders identify the challenges they face and how they articulate development perspectives in relation to available policies. The key findings are twofold. First, that ESI-funded rural development instruments tend to favour place-blind interventions that do little to address peripheries’ economic weakness and lack of institutional capacity. Second, it can be observed that the implementation of ESI funds has so far only marginally stimulated new styles of policy action that shift local actors’ behaviour and expectations of the development policy system. To address growing intra-regional disparities, the case is made for more reflective policy design for strengthening institutional capacities and better integrating peripheries within their regional economies.

INTRODUCTION

This paper contributes to the wider debate on the use of European structural and investment (ESI) funds in the context of increasing socio-spatial polarization across Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Crescenzi & Giua, Citation2014). In these areas, throughout the post-socialist transition the development of urban cores has significantly outpaced that of predominantly rural peripheries (Ehrlich et al., Citation2015). This has been partly due to the shortage of appropriate intervention capacities in demographically shrinking and economically declining peripheralized areas. Bringing together the fields of relational geography and interpretive policy analysis, the paper highlights the beliefs and norms associated with local development in such places. In doing so, we show how local leaders understand using available policy tools to cope with peripheralization (following Kühn, Citation2015) in a context of weak capacity-building instruments and incomplete regional development frameworks. We ask the following question: To what extent do ESI-funded rural development programmes enable local leaders to address processes of peripheralization in one of the least developed areas of CEE? Drawing on the case of Romania’s Sălaj county, we find that existing policies promote a place-blind model of development that furthers the peripheralization of these rural spaces.

TOWARDS AN ACTOR-CENTRED UNDERSTANDING OF PERIPHERALIZATION

Research on the spatial impacts of Cohesion Policy has shown that core cities have benefited more from the policy’s growth opportunities than rural areas outside large agglomerations (Gagliardi & Percoco, Citation2017). To explain these increasing regional disparities between the two types of spaces (cores and peripheries), scholars have adopted a relational perspective by using the concept of peripheralization to signal the solidifying structural disadvantages in peripheries, together with a gradual decoupling of socioeconomic capacities in relation to a dominant core (Keim, Citation2006, p. 3). The key argument is that the development challenges experienced in such areas can only be understood in relation to processes of agglomeration concentrated in urban cores (Ehrlich et al., Citation2015; Keim, Citation2006; Kühn, Citation2015). While the existing literature on the topic already offers great insight into the impact of structural factors on the deepening core–periphery divide, recent scholarship has argued for an actor-centred approach in studying these disparities (Ehrlich et al., Citation2015; Fischer-Tahir & Naumann, Citation2013).

A key factor that hampers the development of growth potential is weak institutional capacities (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). To address this, technical assistance instruments have routinely provided actors with basic support in applying administrative rules. However, peripheral actors have limited capacities for coordinating decision-making and internalizing competences built through the use of ESI funds (Dąbrowski, Citation2014). These places’ deficient capacities to act in a competitive policy delivery system, coupled with demographic challenges, weak economies and exclusion from power-holding networks, weakens their potential for autonomous action and implicitly causes a growing dependence on the centre, thus deepening their level of peripheralization (Ehrlich et al., Citation2015; Keim, Citation2006; Kreckel, Citation2004; Kühn, Citation2015).

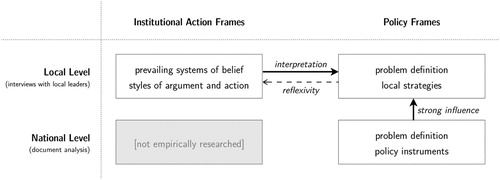

The main aim in this paper is to show how actors affect and are affected by peripheralization in applying rural development policy instruments. Busetti and Pacchi (Citation2014) show that capacity-building is not entirely tied to a specific instrument, but rather depends on the wider policy and institutional context. The conceptual framework therefore draws on frame analysis – an interpretive policy analysis technique that addresses the manner in which actors understand to act upon local development challenges. Following Schön and Rein’s (Citation1994) categorization of action frames, we distinguish two types that are relevant to this study. The first, more grounded, type is called policy frames and is used by institutional actors to construct the problem of a specific policy situation. These frames are constructed by actively selecting, naming and categorizing problematic elements, and ultimately by articulating sequences of projects, using available policy instruments or frameworks as a reference for what is possible or not. The second, more generic and consequently more complex, type of frames is institutional action frames. These bind elements constitutive of institutions – beliefs, or styles of argument and action, to name the most relevant (Schön & Rein, Citation1994, p. 33). These elements shape actors’ expectations of a policy system, even if they cannot precisely delineate its institutional boundaries. Frame analysis serves to emphasize the blend of powerful ideas originating in administrative centres and entrenched local practices. We find this approach to be relevant in the context of Cohesion Policy, given the overt reliance on soft policy transfer, policy benchmarking and incentives as key governance mechanisms (Citi & Rhodes, Citation2007).

METHODOLOGY AND CASE STUDY OVERVIEW

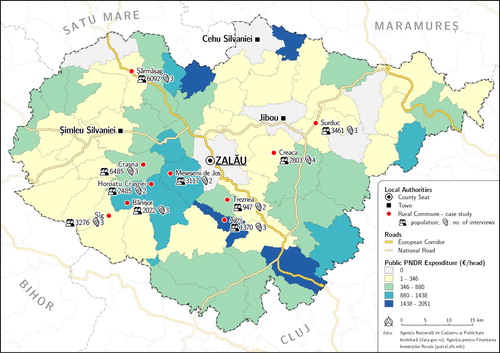

Two reasons underpin the choice of a case in Romania: increasing socioeconomic disparities between its urban growth poles and predominantly rural hinterlands (European Commission, Citation2014), and its limited effectiveness in achieving goals funded through ESI instruments (Szilard & Lazăr, Citation2012). The case study area comprises 10 structurally disadvantaged villages in Sălaj () – the least socioeconomically developed county within the strongly polarized North-West Region (Ionescu-Heroiu et al., Citation2013, p. 240). These villages experience peripheralization to various degrees, according to publicly available statistical data.

Following a qualitative methodological design, we draw on 28 semi-structured interviews with relevant local politicians and public servants, which were conducted in July 2017.Footnote1 The interviews aimed to develop an interpretive account of the overall socioeconomic status of the settlements, while also enquiring into the production and objectives of local development strategies. The fieldwork is complemented by desk policy research on the goals and implementation mechanisms of relevant ESI funds for the 2007–13 multiannual financial framework – i.e., the National Rural Development Programme (PNDR) worth €8.1 billion financed through the European Agricultural Rural Development Fund (EARDF) (based on NSRF, Citation2007; and PNDR, Citation2014). This offers an understanding of available policy options in interpreting interview data, while also illustrating how processes of peripheralization are identified in policy documents and which actions are proposed. The mix of methods allowed us to look at the gap between actors’ interpretation of local development problems and their understanding of existing instruments.

DEVELOPMENT OF ACTION FRAMES TACKLING ISSUES OF PERIPHERALIZATION

The overarching action frames that underpin Romania’s rural development programmes highlight infrastructure (public utilities and services), competitiveness and improvements in governance as key development goals (NSRF, Citation2007, p. 127). To grasp the interplay of action frames in policy responses to issues of peripheralization, we conceptualized two heuristic layers (). First, we summarized the policy frames across national and local government levels. Here, official government documents reveal the overarching national policy frame that targets the issues of rural peripheries, while local actors’ policy frames are derived from their descriptions of the main sources of income for the local population, the types of land usage and strategic development perspectives. Second, by combining respondents’ understandings of the policy system at large, we constructed the broader institutional action frame that guides local actors’ policy actions. While institutional action frames can be found at different levels of government, the analysis focuses on those of local leaders, as this shows the context in which they interpret their actual and potential use of available instruments.

Policy frames

A staple of the national policy frame for rural development has been increasing competitiveness in agriculture. In this sense, financial instruments incentivised the transition from self-consumption-centred farming towards profitable semi-subsistence enterprises in the short run, and scaled production at a future stage (PNDR, Citation2014, p. 271). A set of measures was aimed at raising the appeal of agricultural jobs for entrepreneurial young adults who had turned towards employment in the industrial and service sectors (p. 210), typically located in and around urban centres. This desire for a more efficient way of organizing agriculture is shared in local policy frames. Local actors play an active role in formally and informally disseminating funding opportunities made available through the PNDR. However, complex administrative procedures and the lack of a co-financing mechanism contribute to the structural disadvantages that peripheral actors experience, hampering the policy goal of building a critical mass for semi-subsistence farming: ‘People don’t really dare [to access funds] … I know people who had projects, but didn’t follow through with applications when requirements got complex. They spent money on applying, on assets, and have nothing to show for it’ (local politician, village 7).Footnote2

Besides agriculture, local competitiveness is also understood to stem from improvements in infrastructure. The national policy frame designates infrastructure as a key component of well-balanced regional development, and a core asset that rural areas can use in efficiently competing for investment (PNDR, Citation2014, p. 93). At a local level, infrastructure improvements are also a centrepiece of policy frames, with two broad storylines detailing their contribution to local development. The first draws on the commuter village model, and highlights the role of improved connectivity in facilitating access to jobs already located in the core. The second revolves around maximizing exposure to potential private investors who would typically consider locating in the core. All in all, interviewed actors believe that better infrastructure exposes their locality to exogenous factors that could reverse economic and demographic shrinkage, rather than enable a better use of endogenous potentials. However, peripheral institutional actors are heavily dependent on payment transfers from institutional cores to implement their projects (ESI funds included). We found that this intensified dependency is not problematized in the construction of local policy frames.

The alignment of local and national policy frames ( – strong influence arrow) is a marker that the interviewed local leaders cannot pursue models of local development other than those presented in national policy documents. Leaders can use national policy frames to implement the desired projects, but they encounter difficulties in integrating the new assets in a long-term strategy: ‘The administration went for [an after-school centre] because there were EU funds available. But they didn't consider how to manage it. The local budget cannot afford to financially sustain it’ (public servant, village 5). To address this mismatch, national policy frames rightly hint at the need to address underdeveloped strategic planning capacities. Yet, as the following section will show, this would involve tackling broad (dis)beliefs in the policy system that have solidified over many years.

Local institutional action frames

Local policy frames are constructed through the lens of local institutional action frames. These frames encompass actors’ (in the present case local leaders’) experiences and expectations of the policy system at large, providing the grounds for structuring policy situations ( – interpretation arrow). Such frames are complex and not bound to a specific policy programme or a particular institution. We highlight three prominent elements that constitute these frames: beliefs, styles of argument and styles of action.

Peripheralization processes (particularly weakening economies and demographic shrinkage) lead to shrinking local budgets, to the extent that they barely cover the functioning of public services. Respondents therefore share the belief that sizeable external direct investments (ESI funds included) are the sole enablers of meaningful improvement in their villages. This belief underpins strategic responses in local policy frames (as noted for infrastructure investments), and is driven by observations of positive development that is seen to work in suburbanized rural areas around big agglomerations. A second belief is that weak structural conditions translate to weak political relevance, and hence little importance being given to peripheral areas at the national level. This feeling of being neglected is strengthened by the uniform treatment of all rural areas in development policies, with no accommodation for local specificities in national strategies and programmes, all of which are a-spatial in this sense.

In the interviews, styles of argument were identified with reference to the collaborative structures established through the LEADER local action groups (LAGs) – a supra-local public-private strategy development instrument. This instrument has been widely acknowledged for its potential to generate integrated interventions and enhance the institutional capacities of rural spaces. Yet, we find that the development of impactful partnerships is inhibited by the overall competitive environment for allocating funds, which favours a strong sense of local autonomy and self-interest. Interviewed actors admit to taking part in these structures because of the direct financial benefits. Acting in partnerships continues as long as cooperation is rewarded, with ‘each partner spending the money as they see fit’ (local politician, village 1). This constrains the remit of LAGs to that of a financial instrument.

The limited scope of associative structures favours a style of action that places the responsibility for strategy making and delivery on local leaders, with little support from other levels. Moreover, the rigour required in implementing ESI funds is at odds with an institutional setting where national development funds have been allocated ‘from the centre’ (i.e., national/county administrations):

We had a sewage project already approved, but the government suddenly withdrew the funding. … So then we applied to have the community centre refurbished, but the locals didn’t see that as a priority. They don’t get it: if they [the government] give you money for community centres, that’s what you use it for. You can’t spend it on something else. (local politician, village 7)

With details about funding streams unpredictable, processes of local strategy-making have only given local communities limited opportunity to reflect upon their policy and institutional action frames ( – reflexivity arrow). Rather, they have favoured a purposefully broad style of strategic action that maximizes access to place-blind national policy instruments. Strategic development has therefore been limited to carrying out routine administrative work that is performed by contracted specialists located in major cities, rather than being grounded in impactful local deliberative forums. This approach undoubtedly succeeds in addressing issues that are vital to the general functioning of a community. It nonetheless lacks a place-specific mechanism for addressing peripheries’ economic weakness and limited capacities, by reframing a development path that transcends place-blind measures and mobilizes actors to act upon their priorities.

ENHANCING REFLEXIVE CAPACITIES TO ADDRESS PERIPHERALIZATION

The analysis of the Romanian case study reveals that local leaders have pragmatically oriented their policy frames to those of the national level. It shows that the use of ESI funds has furthered local leaders’ capacities to respond to challenges of peripheralization predominantly in the administrative technical assistance sense, and only marginally, if at all, in the strategic development planning dimension. Thus, there has been a very limited transfer of European Union-inspired policy language into practice, as interventions were conducted in a void of complementary instruments that might have helped actors built up intervention capacities beyond bureaucratic imperatives. This places peripheries on the receiving end of policies designed elsewhere, and limits any growth in their capacity to overcome dependency.

The frame analysis followed in this paper points towards two major observations. First, we observe that local actors in peripheralizing places have had few opportunities to reflect on how they act on development issues. The unchallenged beliefs about wider partnerships, or persistent views of the role of other organizations (as indicated in the institutional action frames) is a telling indicator in this sense. A second observation is that ESI-funded instruments appear to downplay a series of specific factors that shape the dependency relations of CEE rural peripheries, that is, incomplete sectoral reforms, insufficient strategic development capacities or weakened spatial planning systems. Viewed through the lens of local leaders, ESI-funded programmes are more oriented towards the rigorous spending of development funds, with little recognition given to the deeper implications of peripheralization, in particular dependency on cores and weak institutional capacities.

Based on the findings, we highlight two key principles that could inform more reflexive policy designs. The first relates to the building of broader institutional capacities. The fact that actors can comply with the rigorous norms of ESI-funded programmes does not automatically improve their strategic development and planning capacities. National programmes that usually complement ESI-funded infrastructure investments could be decentralized to a regional level and used to enhance institutional capacities in places where they are deficient because they are by design less bureaucratic and therefore able to support more flexible long-term approaches. Actors could, for instance, be supported in conceptualizing economic territorial linkages that are not solely reliant on growth processes within the cores. For this, actors could be motivated to jointly define priorities themselves (rather than aligning with the national priorities and externalizing strategy writing), while also being encouraged to experiment with place-specific implementation arrangements.

A second principle relates to recognizing the need for a long-term engagement and mentorship for enabling this reflexive process. Capacity-building (and economic recovery for that matter) in peripheralizing areas cannot be instant and limited to a programming period or operational programme. New structures introduced to implement ESI funds (e.g., regional development agencies, or the regional offices of the Agency for Rural Investment Financing) are in the best position to fulfil a mentorship role. These organizations were acknowledged positively by the interviewed actors and seen as a trustworthy, helpful source of information.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper shows that ESI-funded policies provide local leaders within one of the least developed areas of the CEE few opportunities for addressing processes of peripheralization. While these places have undoubtedly experienced a significant degree of betterment, the programmes have only to a limited extent generated more inclusive regional development. Rather, increased material and ideational dependencies on the centres could be observed. By highlighting existing development challenges from the perspective of a CEE periphery, this paper signals the need to complement policy designs with instruments that focus on strengthening local-regional capacities for intervention. We strongly emphasize that such instruments should not be restricted to enhancements in programme administration capacities. The claim rather suggests the need for strengthening collaborative, bottom-up policy-making practices in local-regional institutions.

To understand better the potentials of such instruments within the CEE context, upcoming research may consider addressing: (1) the wider multi-scalar context within which people shape their meanings, with a particular focus on national institutional action frames; and (2) means for reframing development in peripheral settings in a way that breaks away from well-established traditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Regional Studies Association for waiving the paper’s processing charge, as well as the editors and reviewers for valuable feedback on earlier drafts. The authors also thank the team at the Faculty of Sociology, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca, for collaboration in conducting the empirical research in Sălaj county.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The fieldwork was organized in collaboration with the Faculty of Sociology, Babeș-Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca. The data were collected by a team of researchers, including one of the authors. All interviews were held in Romanian; relevant quotations have been translated into English.

2 In order to protect the anonymity of the interview partners, the present analysis will not specify exactly which quotation comes from which village, but it rather ascribes to each village a random number from one to ten.

REFERENCES

- Busetti, S., & Pacchi, C. (2014). Institutional capacity for EU Cohesion Policy: Concept, evidence and tools that matter. disP – The Planning Review, 50(4), 16–28. doi: 10.1080/02513625.2014.1007657

- Citi, M., & Rhodes, M. (2007). New modes of governance in the EU: Common objectives versus national preferences. European Governance Papers No. N-07-01. Retrieved from http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/2463/pdf/egp_newgov_N_07_01.pdf

- Crescenzi, R., & Giua, M. (2014). The EU Cohesion Policy in context: Regional growth and the influence of agricultural and rural development policies. LEQS Paper 85. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=2542244

- Dąbrowski, M. (2014). Towards place-based regional and local development strategies in Central and Eastern Europe? EU Cohesion Policy and strategic planning capacity at the sub-national level. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 29(4–5), 378–393. doi: 10.1177/0269094214535715

- Ehrlich, K., Henn, S., Hörschelmann, K., Lang, T., Miggelbrink, J., & Sgibnev, W. (2015). Understanding new geographies of Central and Eastern Europe. In T. Lang, S. Henn, W. Sgibnev, & K. Ehrlich (Eds.), Understanding geographies of polarization and peripheralization. Perspectives from Central and Eastern Europe and beyond (pp. 1–21). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- European Commission. (2014). Partnership agreement Romania – 2014–20. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/partnership-agreement-romania-2014-20_en

- Fischer-Tahir, A., & Naumann, M. (2013). Introduction: Peripheralization as the social production of spatial dependencies and injustice. In A. Fischer-Tahir & M. Naumann (Eds.), Peripheralization: The making of spatial dependencies and social injustice (pp. 9–26). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Gagliardi, L., & Percoco, M. (2017). The impact of European Cohesion Policy in urban and rural regions. Regional Studies, 51(6), 857–868. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2016.1179384

- Ionescu-Heroiu, M., Burduja, S. I., Sandu, D., Cojocaru, S., Blankespoor, B., Iorga, E., … Van der Weide, R. (2013). Full report. Romania regional development program. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Retrieved from http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/12/19060303/romania-competitive-cities-reshaping-economic-geography-romania-vol-1-2-full-report

- Keim, K. D. (2006). Peripherisierung Ländlicher Räume – Essay. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, 37, 3–7.

- Kreckel, R. (2004). Politische Soziologie der Sozialen Ungleichheit. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Kühn, M. (2015). Peripheralization: Theoretical concepts explaining socio-spatial inequalities. European Planning Studies, 23(2), 367–378. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.862518

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. (2014). Programul Național de Dezvoltare Rurală [PNDR] 2007–2013. Retrieved from http://www.madr.ro/docs/dezvoltare-rurala/PNDR_2007-2013_versiunea-septembrie2014.pdf

- Ministry of Economy and Finance. (2007). National strategic reference framework for Romania [NSRF] 2007–2013. Retrieved from http://old.fonduri-ue.ro/res/filepicker_users/cd25a597fd-62/Doc_prog/CSNR/1_CSNR_2007-2013_(eng.).pdf

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. doi: 10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Schön, D. A., & Rein, M. (1994). Frame reflection: Towards the resolution of intractable policy controversies. New York: Basic Books.

- Szilard, L., & Lazăr, I. (2012). The European Union Cohesion Policy in Romania – Strategic approach to the implementation process. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 8(36), 114–142.