ABSTRACT

Shrinkage requires planners to move away from growth-oriented planning towards an adaptive approach. It is puzzling that even after decades of shrinkage, planners can still be stuck with a growth mindset that results in wasted resources and little gain. Existing research has done little to comprehend why planning policy adapts so slowly to shrinkage. The article revolves around the question: What shapes planning policy in shrinking regions? This question is addressed through a case study conducted in the Spanish region of Asturias. The study makes a first analysis of how ideas, interests and institutions influence policy change in shrinking regions. It finds that institutional structures and local interests can be serious obstacles to the adoption of adaptive planning approaches.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

The extent to which shrinkage impacts cities and regions throughout the developed world is forcing planners to adapt to the new realities (Eurostat, Citation2017; Hollander et al., Citation2009; Sousa & Pinho, Citation2015). Given that shrinkage is largely driven by macroregional trends unaffected by local action, planners should transition to an approach that focuses on adapting cities and regions to the realities of shrinkage (Hollander et al., Citation2009; Pallagst et al., Citation2017; Sousa & Pinho, Citation2015). However, not every planner attempts to make this transition (Pallagst et al., Citation2017).

The concept of shrinkage for this paper is taken from Haase et al. (Citation2016), wherein it is conceptualized as a process of change, driven by economic decline, demographic change or suburbanization. Its main indicator is population decline, but the concept is broader and more complex. It encompasses the consequences of decline, such as ageing, segregation and underuse, as well as the policies and decision-making of various layers of government. In short, it concerns the phenomenon that occurs to city or region when it is affected by demographic decline and economic stagnation. Understanding how planning policy changes in shrinking regions could be the key to spread adaptive planning approaches among shrinking regions.

Many authors agree that regional perspective is a crucial to the understanding of this process (Muller & Siedentop, Citation2004; Schlappa & Ferber, Citation2013). Hence, this paper extends the scope of research to the region as a whole instead of merely the urban scope which is featured in majority of literature concerning shrinkage. This article addresses the question: What shapes planning policy in shrinking regions?

The research is built around a case study of the Spanish region of Asturias. In the second half of the 20th century the region experienced shrinkage mostly in the rural areas and the mining towns, in the first decades of the 21st century shrinkage is now visible even in the urban centres of the region. The governments of Asturias, supported by national and European funds, have implemented several strategies addressing shrinkage (Moral et al., Citation2012). Yet, shrinkage has persisted. The combination of sustained population decline with the implementation of various anti-shrinkage strategies makes Asturias the ideal case study.

For the purpose of the study, 18 experts from Asturias were interviewed. The paper offers a novel approach by examining planning strategies in relation to the role of institutions and group interests. It contributes to the planning literature by considering the interaction between governments on a regional level. The article demonstrates that although adaptive planning strategies are implemented locally, there are quite some hurdles to overcome before policy change occurs region wide.

PLANNING IN SHRINKING CITIES AND REGIONS

In recent years, the body of literature concerning shrinkage and planning has grown (e.g., Bernt et al., Citation2012; Rink et al., Citation2012; Sousa & Pinho, Citation2015). Hollander et al. (Citation2009, p. 5) have argued that ‘planners are in a unique position to reframe decline as an opportunity’. Shrinkage relieves regions and cities from the pressures of urbanization creating space to develop natural systems, greener public space or renewable energy (Hollander et al., Citation2009; Power et al., Citation2010). However, before planners will ‘reframe’ decline as an opportunity an attitude change should occur in the planning system (Hollander et al., Citation2009).

Little research has been done to understand how shrinkage is perceived and how that influences planning. Pallagst et al. (Citation2017) have made a start by linking planning strategies to perceptions of shrinkage. They explain that planning strategies can vary from: (1) expansive strategy, where planners seek to reverse shrinkage through urbanization; (2) maintenance strategy, where planners focus on maintaining the attractiveness of cities and towns; and (3) planning for decline, where planner are planning to adapt to the consequences of shrinkage and seek to exploit its opportunities.

Pallagst et al. have paid lesser attention to how these perceptions and strategies are adopted by planners. What is more, they have only considered the role of a single city, leaving aside the influence of other governmental institutions, private parties and other actors. This has obscured the intricate dynamic that persists between these actors in the policy-making process. That is why many authors advocate research on a regional scale, wherein these actors and their influences are considered and understood (Muller & Siedentop, Citation2004; Schlappa & Ferber, Citation2013).

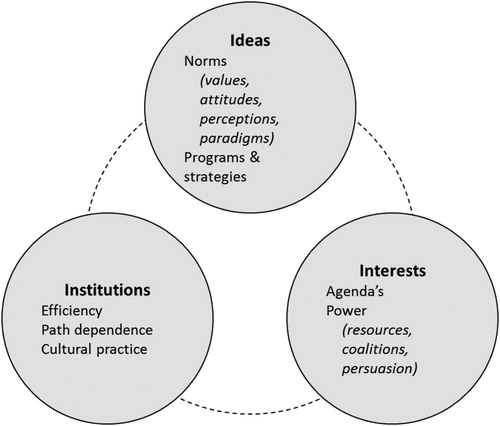

This article bridges the gap by expanding the frame of analysis to the role of institutional structures and powerful interests on a regional level and it examines the influence of these factors on the policy-making process. It builds on the framework by Pojani and Stead (Citation2014), which considers the interaction between three elements: ideas, interests and institutions (). The concept of ideas encapsulates the ‘strategies and attitudes’ that are used by Pallagst et al. (Citation2017). Interests concern the influence of groups on policy change. Institutions concern formal or informal organizations routines, procedures, and conventions which are embedded in the planning system (Pojani & Stead, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Three ‘I’s based on Pojani and Stead (Citation2014).

CASE STUDY CONTEXT: ASTURIAS

Asturias is governed as an Autonomous Community and includes 78 councils. It is characterized by four landscapes: the metropolitan centre dominated by the cities of Gijón, Avilés and Oviedo; the coast with its small fishing villages and holiday villas; the sparsely populated mountainous countryside; and the mining valleys in the south (Roa, Citation2008).

Since the 1980s, total population has declined in the region (). According to the Spanish National Institute for Statistics (INE) Asturias is likely to lose 100,000 inhabitants in the coming 15 years (INE, Citation2016). During the past 80 years, it is possible to distinguish different variations of shrinkage throughout the region.

Table 1. Population development of Asturias from 1900 to 2017.a

In the beginning of the 20th century, the Asturian mining industry experienced a large boom. Its mining industry attracted population from the rural countryside and the adjoining regions (Prada Trigo, Citation2012, Citation2014). Thus, driving shrinkage in the rural countryside and leaving many hamlets and agricultural lands abandoned.

After the 1960s, the mining sector entered a downward spiral (Prada Trigo, Citation2012). Industrial activity was relocated to the port of Avilés and Gijón (Moral et al., Citation2012). Thus, spurring the decline of mining valleys of Caudal and Nalón, which lost over 30% of their population and turned into industrial waste lands (Prada Trigo, Citation2012).

The re-concentration of the industry temporarily boosted economic and demographic growth in the central cities (Prada Trigo, Citation2012). The further decline of the European coal market, together with an ageing population have now even led shrinkage to affect the larger central cities.

METHODOLOGY

The study uses qualitative research methods to analyse policy change. The research draws on 18 semi-structured interviews with experts at government institutions, research institutions and universities in Asturias. Interviewees were asked to reflect on the impact of shrinkage, as well as on the primary projects and programmes that were undertaken by the local and regional governments to mitigate shrinkage. The gathered data were categorized according to the conceptual framework described above ().

SHRINKAGE AND PLANNING POLICY IN ASTURIAS

Based on the framework (), this section outlines the main results that were generated through the research. It points out the attitudes that are present in the planning strategies, and how the institutional structure and the interests complicate regional action.

Ideas

The analysis of the Asturian planning system demonstrates different attitudes and approaches towards shrinkage. The larger councils of Avilés, Oviedo and Gijon are transitioning to a planning policy that acknowledges the reality of shrinkage. The councils focus policy on maintaining the attractiveness of their inner cities (interviewees 13 and 15). The cities have invested in diversifying the local economy by subsidizing innovative industries. In Avilés and Gijón programmes were initiated to address the social problems such as the isolation of the elderly population in the periphery of the cities (interviewee 16).

However, planners of these same cities have been responsible for the large-scale urbanization, visible on the periphery of the central cities. Many of these areas lie vacant, because the supply of land outweighs demand (interviewees 1, 2, 4 and 5). This expansive strategy is also visible in the smaller councils around the regional centre and on the coast (interviewees 1 and 2).

An example of a more adaptive policy approach is the recently published Plan Demográfico del Principado de Asturias 2017–2027, which specifically addresses the declining population in the rural councils. The plan is concerned with consolidating the services, and seeks to attract people to the rural areas. Interviewees entrusted little faith in the effectiveness of the plan, since it is conceived solely by the regional department of presidency and citizen participation, without support or collaboration from other departments or local governments (interviewees 1, 2 and 4).

Interviewees also indicated the persistence of an attitude of pessimism held by the regional governments and the general public (interviewees 1 and 16). This pessimistic attitude was not only directed towards the Plan Demográfico. Interviewees commented on the numerous European Union-funded projects that failed over the years (interviewees 1, 2 and 4) and other plans were said to be plagued by bureaucracy and corruption (interviewee 16). Especially in the councils outside the region’s centre, this has led the general public and their representative democratic leaders to become disillusioned with ‘new’ plans in general. Interviewees agreed that planning in Asturias should focus more on liveability and sustainability. However, they found it difficult to imagine that reframing shrinkage as an opportunity would be accepted in the political climate that has emerged during the years of decline (interviewees 5, 6 and 10).

Interests

As interviewees (1, 2 and 16) indicated, ongoing decline pushed smaller councils to be more competitive for development and resources. The regional government has been trying hard to coordinate regional development and mitigate some of these excesses. However, efforts to establish a regional plan have been blocked by the councils for more than a decade (interviewees 1 and 2). Recently, a new planning process has been initiated in collaboration with the councils. Yet, interviewees (1 and 2) had little confidence in its success. This is partly because of the political diversity among the councils, but also because incentives created by the land-tax system remain unchanged (interviewees 1 and 2).

Land taxes are one of the largest sources of income for Asturian councils. The more land is built up, the more taxes the councils receive. Especially for smaller councils, this has created an incentive to give developers building permission, even if there is no demand (interviewees 1 and 2). This has resulted in many vacant apartment buildings and a large quantity of holiday homes.

Institutions

Many interviewees agreed that the regional planning system is extremely restrictive. It is characterized by a strong hierarchy and a focus on legislative policies (interviewee 4). Little effort has been made to facilitate the interaction between the different levels of government (interviewees 2 and 4). Policies and programmes are developed at the regional government, and rarely in collaboration with the local councils (interviewees 1 and 16).

There is another reason why regional planning structures are hard to maintain in Asturias. Independence is a central value in the Asturian planning culture. Losing competence or merging with other councils is seen as an affront to that value (interviewees 1–3 and 10). This is one of the reasons why there are so many smaller councils in the region. It drives councils to resist any effort to coordinate planning on a regional level, for fear of losing control (interviewees 10–12).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The article sought to understand: What shapes planning policy in shrinking regions? The analysis demonstrates a complex dynamic of interactions between the three ‘I’s. It shows that in Asturias, at least some planners have transitioned to a more realistic approach towards shrinkage, though it is still too early to speak of a truly adaptive approach.

However, it also shows that different attitudes can persist within one planning system and even within one planning department. The lack of interaction between government institutions has caused such initiatives to remain within separate institutions, and has limited region wide policy change. Despite its decades of decline several councils in the region are still implementing growth-oriented strategies.

Interestingly, the effects of shrinkage have made collaboration even more difficult, because it incentivized councils to compete for development and resources and resist regional control. What is more, particularities in the planning system – such as taxing regulations – can form significant factors to resist policy change.

One of the most salient findings is the pessimism towards new planning approaches which had arisen during the regions long and steady decline. Interviewees felt that this lack of faith in the ability of planners to come up with suitable solutions to the regions problems might be an even bigger hurdle for regional policy change. This pessimism throws doubt on the notion that planners would ever be able to reframe shrinkage as an opportunity.

The empirical evidence presented in this paper offers insight into the complex dynamic of policy change in shrinking regions. It expands the scope of the body of literature by considering local planning structures and cultures and demonstrates how they can be obstacles for policy change. It also calls for the consideration of the variety of attitudes towards shrinkage that can persist within one region, and the difficulty that might be involved in changing those attitudes. This study can assist planners and policy-makers who seek to implement adaptive planning approaches in shrinking regions.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- Bernt, M., Cocks, M., Couch, C., Grossmann, K., Haase, A., & Rink, D. (2012). Shrink smart the governance of shrinkage within a European context. Shrink Smart. Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research-UFZ.

- Eurostat. (2017). Projected percentage change of the population, by NUTS 3 regions, 2015–50. In b. N. r. Projected percentage change of the population, 2015–50 (¹) (%) RYB2016.png (Ed.), (Vol. 584 KB).

- Haase, A., Bernt, M., Großmann, K., Mykhnenko, V., & Rink, D. (2016). Varieties of shrinkage in European cities. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(1), 86–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413481985

- Hollander, J. B., Pallagst, K., Schwarz, T., & Popper, F. J. (2009). Planning shrinking cities. Progress in Planning, 72(4), 37.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2016). Proyecciones de Población 2016–2066. Geraadpleegd van. https://www.ine.es/prensa/np994.pdf

- Moral, S. S., Méndez, R., & Trigo, J. P. (2012). Aviles (Spain): From urban decline to the definition of a new development model. In C. Martinez-Fernandez, N. Kubo, A. Noya, & T. Weyman (Eds.), Demographic change and local development: Shrinkage, regeneration and social dynamics (pp. 113–119). OECD.

- Muller, B., & Siedentop, S. (2004). Growth and shrinkage in Germany – trends, perspectives and challenges for spatial planning and development. https://difu.de/publikationen/growth-and-shrinkage-in-germany-trends-perspectives-and.html

- Pallagst, K., Fleschurz, R., & Said, S. (2017). What drives planning in a shrinking city? Tales from two German and two American cases; in: Town planning review, special issue on shrinking cities. Town Planning Review, Special Issue on Shrinking Cities, 88(1). https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2017.3

- Pojani, D., & Stead, D. (2014). Ideas, interests, and institutions: Explaining Dutch transit-oriented development challenges. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 46(10), 2401–2418. https://doi.org/10.1068/a130169p

- Power, A., Plöger, J., & Winkler, A. (2010). Phoenix cities: The fall and rise of great industrial cities. Policy Press.

- Prada-Trigo, J. (2012). Urban decline and failed reconversion process: The role of ‘path dependence’ and governance theories in local actors’ strategies. The case of Langreo (Spain). Romanian Review of Regional Studies, 8(2). https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/2029/2ac0e8fa03e5b478f1cfaecf00ae2f9dfa44.pdf

- Prada-Trigo, J. (2014). Local strategies and networks as keys for reversing urban shrinkage: Challenge and responses in two medium-size Spanish cities. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift – Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(4), 238–247. doi: 10.1080/00291951.2014.923505

- Rink, D., Bernt, M., Cocks, M., Couch, C., Grossmann, K., & Haase, A. (2012). The governance of shrinkage within a European context.

- Roa, M. C. D. (2008). Multi-level polycentric spatial development: The Asturias Central Area.

- Schlappa, H., & Ferber, U. (2013). From crisis to choice: Managing change in shrinking cities. Local Land and Soil News.

- Sousa, S., & Pinho, P. (2015). Planning for shrinkage: Paradox or paradigm. European Planning Studies, 23(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.820082