ABSTRACT

In recent decades, regional development has seen a wave of collective policy-making processes such as the European smart specialization approach or participatory approaches to tourism strategy formulation. These processes are confronted by several challenges based on behavioural patterns related to human agency. This paper conceptualizes collective regional policy-making processes in a behavioural perspective. It argues that concepts known from behavioural economics can contribute to our understanding of the agency-related challenges in collective regional policy-making processes, and that mitigating the role of human agency can help overcome these behavioural challenges. Case studies from three Austrian provinces show how major challenges to collective policy-making processes can be explained behaviourally, and how these challenges can be countered by mitigating strategies that employ expertise, moderation, indirect participation, delegation of prioritization and evidence.

INTRODUCTION

In recent decades, regional development has seen a rise of collective policy-making processes such as smart specialization (Foray et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015) or participatory tourism strategy processes. However, collective regional policy-making processes are confronted by several challenges discussed in the literature (e.g., Benner, Citation2019b, Citation2019c; Capello & Kroll, Citation2016; Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Karo et al., Citation2017; Sotarauta, Citation2018; Storper et al., Citation2015; Trippl et al., Citation2019) that are related to the role of human agency and behaviour.

At a theoretical level, a renewed interest in the role of human agency and underlying behavioural patterns in regional and urban development seems to emerge. Indeed, Huggins and Thompson (Citation2019, p. 121) see ‘a (re)turn to addressing the role of individual and collective behaviour’ in economic geography. This interest is consistent with the widespread attention paid to behavioural economics (BE). The last decades have seen the emergence of a large body of literature on BE (e.g., Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979, Citation1984; Thaler, Citation1980; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981, Citation1991, Citation1992). In terms of policy, BE has been applied to improve the effectiveness of policies in areas such as energy, consumer protection, health or financial products (e.g., Lourenço et al., Citation2016; OECD, Citation2017; Troussard & van Bavel, Citation2018).

In regional development, BE has been applied to address the role of personality traits for entrepreneurial or political agency and the impact of these traits on economic growth (Garretsen et al., Citation2019; Huggins & Thompson, Citation2019; Lee, Citation2017; Obschonka et al., Citation2013; Rentfrow et al., Citation2015), operational aspects of regional policy such as conditionalities, incentives, and monitoring and evaluation (OECD, Citation2018), or the specific problems in the tourism sector (Benner, Citation2019a; Juvan & Dolnicar, Citation2014; Kallbekken & Sælen, Citation2013).

Still, while the literature available addresses mostly microlevel aspects, there remains a gap in understanding how behavioural patterns affect the meso-level of regional development, that of regional policy-making and governance. Problems found at this level could be called regional-policy meta-problems. They include limited capabilities of public authorities in planning and implementing collective policy-making processes, difficulties in effectively prioritizing public interventions and spending, or the ‘regional innovation paradox’ (Oughton et al., Citation2002) that regions most in need of effective regional innovation policies tend to have the weakest capabilities to implement them (Capello & Kroll, Citation2016; Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Karo et al., Citation2017; Sotarauta, Citation2018; Trippl et al., Citation2019).

Regional policy design, particularly in collective policy-making processes, is a relational process driven by agency and marked by contextuality, contingency and path dependence (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003). Thus, to understand meso-level meta-problems, linking them to the microlevel of individual behaviour is necessary, and behavioural approaches can help understand these problems. To the author’s knowledge, the role of human agency in regional policy-making processes has barely been analysed from a behavioural perspective so far. This paper attempts to close this gap by applying several BE concepts to challenges found in collective policy-making processes in the context of current European regional policy, and thus seeks to contribute to the microfoundation of regional policy concepts. In particular, it addresses the questions of which behavioural constraints of human agency lead to suboptimal outcomes of collective regional policy-making processes, and which mitigation strategies can counter these constraints. The paper is exploratory and aims to provide a conceptual basis for further, more in-depth research, and it draws on empirical case studies from three Austrian provinces to demonstrate the utility of the conceptualization.

The paper is structured as follows. The next section conceptualizes collective regional policy-making processes from a behavioural perspective. The paper then examines some of the problems encountered in collective policy-making processes. It then uses behavioural approaches to interpret these problems and proposes a framework to link regional policy-making problems with BE. Empirical case studies from three Austrian provinces, Tyrol, Styria and Burgenland, apply this framework and lead to an outlook towards further research.

CONCEPTUALIZING COLLECTIVE REGIONAL POLICY-MAKING PROCESSES

Departing from the top-down orientation of former regional policies, contemporary regional development has largely adopted a perspective of collective decision-making. This trend has a theoretical corollary in the turn towards institutional (e.g., Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013; Rodríguez-Pose & Storper, Citation2006) or relational (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003; Storper, Citation1995, Citation1997) approaches. The 1990s and early 2000s saw a growing interest in regional development based on cooperation between agents in regional innovation systems (e.g., Cooke et al., Citation1997), learning regions (e.g., Morgan, Citation2007), Italian industrial districts (e.g., Becattini, Citation1991) or ‘Silicon Valley’-type clusters (e.g., Saxenian, Citation1994). Collaboration builds on aspects of individual agency and inter-agent relationships (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003) and thus on patterns of behaviour. As Huggins and Thompson (Citation2019) argue, institutions and behaviour are intricately related. It is thus fair to assume that collaboration does not simply happen but requires a common basis, or what could be called ‘regionalist behaviors’ defined as ‘institutionalized capacities to do things together’ (Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 139). Regionalist behaviours draw on constructs such as narratives and visions shared by a critical mass of regional agents. For instance, in the cases of the San Francisco Bay Area and Greater Los Angeles, Storper et al. (Citation2015) describe how narratives held by regional policy-makers and business leaders shaped economic development paths.

A narrative can be understood as an explanation of a region’s development that helps policy-makers and business leaders make sense (Fleming, Citation2001, pp. 34–35) of the current state of the regional economy. Thus, a narrative is a leadership instrument to cope with ambiguity and uncertainty by interpreting reality (Fleming, Citation2001). A shared vision (Sotarauta, Citation2018) helps agents imagine what their regional economy might eventually look like. Under uncertainty, a vision represents the scenario of the future desired by agents. Using Fleming’s (Citation2001, p. 35) image of a map, we might understand a vision as the destination and a narrative as the map which offers a simplified representation of a complex reality and a route towards the destination.

However, narratives and corresponding visions do not have to continue actual evolutionary dynamics in the regional economy such as pathways (e.g., Benner, Citation2019c; Grillitsch et al., Citation2018; Isaksen et al., Citation2018). If they do, we might speak of a persistent trajectory that is not directed at radical change in the regional economy. Alternatively, for instance in a lock-in situation (Grabher, Citation1993), a vision may have to break with established trends in what could be called a disruptive trajectory but doing so will require a new narrative that offers a new interpretation of reality.

Narratives underlie collective regional policy-making processes, and visions are formulated there. Based on Hausmann and Rodrik’s (Citation2003) idea of ‘self-discovery’ of economic and technological tendencies and capabilities by public and private-sector agents (Hausmann & Rodrik, Citation2003; Martínez-López & Palazuelos-Martínez, Citation2015), these collective processes have become ever more important in recent decades. Examples include joint public–private efforts to design regional tourism strategies or current European Union (EU) Cohesion Policy that calls on regions to design smart specialization strategies. These strategies, commonly called research and innovation strategies for smart specialization (RIS3), are meant to prioritize areas of diversification to be promoted by the EU’s Structural Funds, and to be designed in a so-called entrepreneurial discovery process (EDP) that brings together policy-makers, administrators, firms, academia and associations in formats such as conferences, surveys, focus groups or face-to-face interviews (Foray et al., Citation2009, Citation2012; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019; McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015; Radosevic, Citation2017).

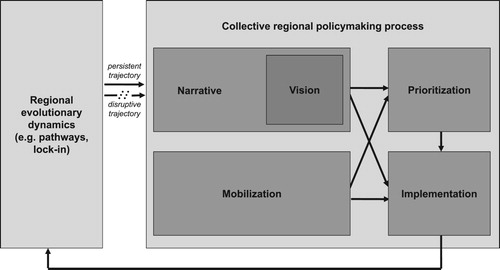

In an attempt to capture the complex and cyclical relationships between the steps laid out, depicts a stylized conceptualization of collective regional policy-making processes. Actual evolutionary dynamics in a regional economy condition the narrative pursued, either in a persistent trajectory or in a disruptive one. The narrative and its vision condition the prioritization undertaken in a self-discovery process and the subsequent implementation of the resulting strategy, but both are dependent on the mobilization of agents. Implementation, in turn, impacts actual evolutionary dynamics.

Figure 1. Stylized conceptualization of collective regional policy-making processes. Source: Author’s elaboration.

However, in practice the cycle depicted in is not always smooth. Each step faces particular challenges. The next section presents some of these common challenges.

CHALLENGES TO COLLECTIVE REGIONAL POLICY PROCESSES

In a market-based system, any self-discovery process by definition has to involve private-sector firms, but mobilizing them is particularly difficult, probably more so than mobilizing public-sector or academic agents (e.g., Capello & Kroll, Citation2016; Grillo, Citation2017; Karo et al., Citation2017; Sotarauta, Citation2018). While the region as a whole might eventually benefit from broad participation of private-sector agents, each one individually has to bear the cost (notably in terms of time lost for day-to-day business), a dilemma reminiscent of the tragedy of the commons (Hardin, Citation1968). Further problems include rent seeking (Krueger, Citation1974) by narrow vested interests (e.g., Grillitsch, Citation2016; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019, pp. 2055–2056), blockade by agents fearing to be on the losing side (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2000; Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 217), or the emergence or maintenance of an inward-looking vision (Benner, Citation2019c). Overcoming these challenges is crucial particularly if the course of a regional economy is to be changed in a disruptive trajectory, as may be relevant when new economic paths are to be promoted (Benner, Citation2019c; Sotarauta, Citation2018, pp. 193–197).

Even if mobilization succeeds, achieving a vision shared among agents is not easy. Instead of identifying a common vision in a harmonious way, a process that involves a multitude of actors may be ‘an arena for discussions, battles and quarrels’ (Sotarauta, Citation2018, p. 197). While this is not in and of itself problematic, the outcome is far from certain. In the best of cases, these battles could evolve into a beneficial negotiation process, but they could equally thwart the process by detracting agents from agreeing on a forward-looking vision. In the other extreme, agents involved in collective regional policy-making processes may be carried away by their own enthusiasm and an overestimation of what they can actually control, leading to costly over-optimism. Large-scale infrastructure or megaprojects and the often unjustified hopes attached to them (e.g., Flyvberg, Citation2009; Storper et al., Citation2015, pp. 125–128) can serve as examples. The outcomes of regional development strategies are fundamentally uncertain because regional policy operates in an environment marked by contingency, contextuality and path dependence (Bathelt & Glückler, Citation2003). The more ambitious a strategy, the higher the probability of over-optimism involved, possibly resulting in frustration and a loss of credibility of the policy-making process itself.

When it comes to prioritization, collective regional policy-making processes face problems in defining appropriately precise and context-specific priorities. Empirical evidence on smart specialization hints at the difficulty for agents to prioritize with an adequate degree of precision and selectivity (Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Karo et al., Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2019).

Depending on the narrative followed by agents, collective regional policy-making processes may lead to lock-in (Grillitsch, Citation2016, pp. 32–33; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019, pp. 2055–2056) by pursuing a persistent trajectory instead of embarking on a disruptive trajectory. The primary problem, then, is an inability to develop a forward-looking vision. Agents may settle on a backward-looking vision that draws on dreams about a glorious past and lacks transformative ambition. In this case, opportunities to facilitate new path development may be wasted (Benner, Citation2019c).

While these problems have a variety of reasons including institutional, organizational or capacity-related ones (Benner, Citation2019b; Capello & Kroll, Citation2016; Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019; Sotarauta, Citation2018; Trippl et al., Citation2019), it is fair to assume that a collective process that gathers a multitude of agents exhibits specific behavioural patterns of agency that condition the course of the process. The next section briefly introduces selected concepts known from BE and relates them to the challenges presented.

A BEHAVIOURAL PERSPECTIVE ON REGIONAL POLICY-MAKING CHALLENGES

Starting from the basic assumption of ‘bounded rationality’ (Simon, Citation1982), some concepts known from BE can serve to elucidate behavioural patterns of agency behind the challenges confronting collective regional policy-making processes.

To start with, it seems reasonable to assume that a collective policy-making process is based on participating agents’ reference points (Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1992). When evaluating the utility of decision outcomes, agents consider their reference point, and their evaluation is marked by loss aversion (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 278–299, 302–303; Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1979, Citation1984; Loewenstein, Citation1988; Payne et al., Citation1980; Shefrin & Statman, Citation1985; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1991, Citation1992). Loss aversion makes change particularly difficult if there are probable losers (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 304–305) that may choose to block change (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2000; Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 217). As a result, agents may prefer the status quo and tend to overvalue it while underestimating opportunity costs, a phenomenon known as ‘endowment effect’ (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 292–297; Knetsch, Citation1989; Thaler, Citation1980, pp. 43–47). Reference points are shaped by narratives. For instance, in the case of Greater Los Angeles, the reference point of low-cost comparator regions shaped the narrative pursued (Storper et al., Citation2015, pp. 143–144, 167–168).

Similarly, framing (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 335–336, 363–374; Kahneman & Tversky, Citation1984; Loewenstein, Citation1988; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981) shapes agents’ perceptions that underlie their behaviour. A frame is a conception held by an agent that is affected by how problems or situations are represented (Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981, p. 453), and can be thought to include the possible evolution of agents’ preferences in the future to prevent a ‘projection bias’ (Loewenstein et al., Citation2003). In the context of regional development, a frame could be described as the abstract space of possible narratives for agents to adopt. Agents make different decisions according to how scenarios are framed, and adopting a too narrow frame can lead to suboptimal decisions (e.g., Kahneman, Citation2011; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1981) by adopting a misguided narrative. Hence, if collective policy-making processes are supposed to facilitate the adoption of a forward-looking vision for regional development, predefining a wide frame for discussions seems sensible.

In collective policy-making processes, agents may find it difficult to take an outsider’s view (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 245–254) and may fall prey to a ‘planning fallacy’ (Kahneman, Citation2011, p. 249), that is, adopting unrealistic plans in a state of over-optimism (Flyvberg, Citation2009; Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 249–251; Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008). Overconfident decision-makers overestimating their own capabilities (Larwood & Whittaker, Citation1977) or the predictability of outcomes (Alpert & Raiffa, Citation1982) may intensify the phenomenon. The problems plaguing large-scale infrastructure or megaprojects (Flyvberg, Citation2009; Kahneman, Citation2011, p. 250; Storper et al., Citation2015, pp. 125–128) belong into this category.

Once over-optimism gives way to reality and plans implemented prove to be unrealistic, the ‘sunk-cost fallacy’ (Kahneman, Citation2011, p. 253) and the notion of ‘mental accounts’ (Odean, Citation1998, p. 1779) come into play. Instead of discontinuing or radically changing failed plans, agents may feel committed to continuing them (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 342–346; Thaler, Citation1980, pp. 47–50) and feel that giving up the plan would constitute an actual loss (Odean, Citation1998).Footnote1 Continued investment in those science and technology parks that do not prove successful over time (e.g., Castells & Hall, Citation1994; Phillimore & Joseph, Citation2003, p. 755; Rodríguez-Pose & Hardy, Citation2014) may serve as an example where the sunk costs of investments made are particularly obvious.

When faced with risky decisions, agents may be motivated by the fear for eventual regret (Bell, Citation1982; Loomes & Sugden, Citation1982) or disappointment (Loomes & Sugden, Citation1986) when the consequences of a decision made eventually turn out to be adversarial, and may refrain from making active decisions in the first place. This behaviour leads to a bias towards inaction (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 346–349; Thaler, Citation1980, pp. 51–54).

Further, the bias for inaction is rooted in decision-makers’ tendency to stick with default options (Thaler & Sunstein, Citation2008) or, in other words, to exhibit a ‘status quo bias’ (Samuelson & Zeckhauser, Citation1988). This bias may explain prioritization problems in collective regional policy-making processes (Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Karo et al., Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2019) because sticking with wide priorities defined in previous regional policies is the easy default option while agreeing on more selective priorities involves making painful decisions.

summarizes several scenarios, salient challenges and behavioural concepts that can help understand these challenges.

Table 1. Behaviourally based challenges in regional policy-making processes.

On the level of the narrative followed, agents can misinterpret the ‘development club’ (Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 143) a region belongs to, for instance when agents in a region with high land prices focus on reducing costs for businesses and on calling for weaker regulation (Storper et al., Citation2015). In such a case, the narrative is misguided. When misinterpreting the development club, agents adopt a too narrow frame of the choices feasible (e.g., cost competition) and compare their region with a wrong set of comparators, thus setting an inappropriate reference point. Here, the evidence base used in collective policy-making processes can play a major role in proposing a wide frame and, if and when interregional comparisons are made, selecting an appropriate set of comparators.

As the general narrative, the vision emerging in a collective policy-making process can be misguided. When pursuing a disruptive trajectory, agents may prove unable to achieve a sufficiently transformative vision but instead end up with a backward-looking vision and lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993; Grillitsch, Citation2016; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019) in the established narrative. Lock-in is an obvious example for sticking with the default option and for fearing possible regret and disappointment when taking action, and a backward-looking narrative and vision is a problem of adopting a narrow frame. In addition, the projection bias may be at play. In this scenario, place leadership (Sotarauta, Citation2018; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017) and political agency (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2019) in framing the stakes and in motivating agents to look forward may prove vital. Another problem related to the vision is over-optimism (Storper et al., Citation2015, pp. 125–128). In this case, the emerging vision is unrealistic. The planning fallacy is involved and may be alleviated with a ‘premortem’ (Klein, Citation2007, p. 18) exercise that encourages agents to voice concerns about plans, and to reflect about possible reasons for failure and solutions that increase the robustness of planning (Kahneman, Citation2011, p. 264; Klein, Citation2007).

Mobilization problems, notably among private-sector firms, may occur if the prospect of reaching a new vision for regional development seems unattractive to (some) agents (Capello & Kroll, Citation2016; Karo et al., Citation2017; Sotarauta, Citation2018). In the case of a persistent trajectory, for those agents who find the vision emanating from the dominant narrative unattractive or simply unexciting, not participating in the process is the default option. In the case of a disruptive trajectory, things are much tougher since agents that fear to be on the losing side of the new vision may block the process (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2000; Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 217). In this case, loss aversion plays a strong role. Adopting a wider frame can help but may not suffice to overcome active resistance by potential losers. Assembling a strong enough coalition for change may be a possible way out but is not a simple task either.

In the prioritization phase, difficulties for agents to set adequately precise and selective priorities (Gianelle et al., Citation2019; Karo et al., Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2019) may be related to an unclear narrative or to different or divergent ones held by various agents. Behavioural explanations include the ease of sticking with the default option by setting wide priorities and practically not prioritizing at all, a fear of regret or disappointment for selecting priorities that eventually turn out to be the ‘wrong’ bet, the sunk-cost fallacy and mental accounts preventing the deselection of previously promoted priorities that proved unpromising, and loss aversion and the endowment effect on the part of agents affected by deselected priorities. Overcoming this scenario seems difficult because tough choices are involved in any prioritization exercise. Higher level incentives such as EU conditionalities (e.g., Benner, Citation2019b; OECD, Citation2018) might help, and so could solid evidence on which priorities are promising and which ones are not. However, prioritization problems can be related to purposeful rent seeking (Krueger, Citation1974) or to the capture of the process by narrow vested interests or insiders (Benner, Citation2014, Citation2017; Grillitsch, Citation2016; Hassink & Gong, Citation2019, pp. 2055–2056; Kyriakou, Citation2017, p. 31; Trippl et al., Citation2019). This risk is particularly high if a few dominant agents succeed in dominating the agenda (Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 168) while moderation can mitigate it (Grillitsch, Citation2016, p. 32).

Finally, when it comes to the implementation stage of the strategy, over-optimism during the policy-making process can lead to frustration among agents and to the delegitimization of the process. To alleviate this danger, policy-makers should be aware that collective processes using formats such as large conferences may promote groupthink and, hence, limit critical thinking (Kahneman, Citation2011, pp. 85, 264–265; Storper et al., Citation2015, p. 171). While exercises such as the ‘premortem’ (Klein, Citation2007, p. 18) can mitigate the risk in particular scenarios, it seems wise to recommend a triangulation of methods, for example, by complementing multilateral formats such as conferences with bilateral ones such as qualitative interviews and by drawing on objective evidence and expert knowledge to assess the prospects of successful implementation of the strategy.

CASE STUDIES

The three Austrian provinces of Tyrol, Styria and Burgenland offer a rich context for studying collective policy-making processes since they have regional economic, innovation or tourism strategies that were developed in participatory processes. Collective policy-making has a long history in Austria, going back to the 1990s, and involves agents such as provincial (regional) governments, firms, business promotion agencies, universities, business associations and chambers of economy or labour (Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning, Citation2016; Benner, Citation2019b). While the uniform national context allows for focusing on regional specifics, the three provinces are structurally different. According to the provincial profiles described by the Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning (Citation2016, pp. 28–30), Styria is one of Austria’s traditional industrial heartlands with high research and development (R&D) intensity but at the same time a very diverse region that contains the country’s second largest urban centre, Graz, as well as peripheral regions. Tyrol is one of Austria’s primary tourist destinations with a small number of larger R&D-intensive firms and a service-based economy. Burgenland is Austria’s weakest regional economy that is mainly rural, has an economic tissue with weak R&D intensity and used to be Austria’s only convergence region under EU Cohesion Policy (pp. 28–30).

The case studies draw on 17 telephone interviews conducted in September and October 2019. The semi-standardized interviews took between 11 and 64 min, with an average of 29.5 min. The number of interviews was guided by the goal of reaching theoretical saturation, and indeed the significance of new insights decreased as more interviews were conducted. However, not all interviews solicited took place since the strategy processes occurred several years earlier and some participants had retired or changed jobs in the meantime. Interviewees included representatives of provincial governments, regional development agencies, chambers of economy, universities and national-level experts. In selecting interviewees, lists of participating agents included in published strategies were considered where available, as were recommendations by other interviewees.

Tyrol

In 2013, the provincial government of Tyrol published its RIS3. The strategy’s vision focuses on maintaining the competitiveness of the regional economy, and the strategy’s pillars focus on enhancing the economy’s strengths and on seizing synergies through cooperation. Sectoral priorities were based on previous policies such as cluster support. Hence, the strategy can be seen as pursuing a persistent trajectory. The EDP included, inter alia, representatives of the provincial government, firms, universities, the regional development agency, business association and chamber of economy (Provincial Government of Tyrol, Citation2013).

Agents’ views and priorities were solicited in face-to-face interviews and summarized for discussion meetings. A study on the regional economy was commissioned to provide evidence for the discussions. In meetings and workshops, agents were asked for perceived strengths, challenges and possible developments. Expert support by a moderator internal to the region but external to the provincial government helped the organizers in taking an outside view and in asking critical questions, possibly preventing capture of the process by vested interests.

The process followed an inclusive approach by not imposing selectivity in terms of agents’ priorities. The result was that the process went smoothly and without conflicts or controversial discussions, but the eventual RIS3 exhibits a low degree of selectivity in the priorities it defines. To focus the discussion on the possibilities and constraints on the regional scale and to prevent the danger of discussions drifting towards other scales (e.g., the federal level), the moderator continuously engaged in framing the discussion to regional subjects.

A more selective approach was taken when work programmes were designed. Organizers made clear to agents at the outset that prioritization would be necessary because of budget constraints, and the resulting work programmes with their selective prioritization were generally accepted. This process, however, was done not in plenary sessions but in bilateral meetings with the moderator and the draft work programme was shared with all agents for comments afterwards.

Tyrol’s current tourism strategy was published in 2015 but was preceded by a series of consecutive strategies since the mid-1990s. The predecessor strategy dating from 2008 was evaluated by experts. This evaluation shaped the narrative the new strategy’s vision was built on. This vision stresses the balance between tourism and liveability, the role of family-run tourism businesses, and innovative leadership in alpine tourism and related training, education and R&D (Province of Tyrol et al., Citation2015).

While the strategy pursues a persistent trajectory by continuing the long-standing thrusts of Tyrol’s tourism policy, the focus on liveability and inhabitants’ attitudes towards tourism is somewhat new. While the sustainability of tourism is an older debate in Tyrol and while there was a long-standing consensus among agents not to define quantitative objectives on the strategic level, the present strategy explicitly defines the compatibility between tourism and liveability as a strategic guideline and for the first time includes the environment and climate as a field for action.

The strategy was developed in a circle of representatives of the provincial government, the federation of local tourism associations, the chamber of economy and the regional tourism marketing organization. These agents coordinated with affiliated agents such as local tourism associations or chamber subentities for the hospitality industry. Firms were informed about the results during a conference for the tourism industry and in a tourism-specific journal. The process built on the evidence provided by the results of the expert evaluation and further studies, and the prioritization of strategic guidelines was shaped by these results. Similar to the RIS3, the process was moderated by an expert to prepare the evidence for the discussions and to ask critical questions.

Styria

Styria’s RIS3 defines the vision of strengthening the knowledge intensity of the economy with a focus on manufacturing (Provincial Government of Styria, Citation2016), a vision that is consistent with the long-standing narrative of the region recovering from its 1980s crisis provoked by the decline of the formerly nationalized steel and mining industries.

The RIS3 was an update of the previous strategy dating from 2011. Despite the desire to achieve more focus, the RIS3 continues the general thrust of priorities promoted under previous policies, thus proving a case for a persistent trajectory. The participation process basically included discussions with agents on the basis of an expert draft. Agents’ opinions were solicited and later discussed. Agents involved included the chambers of economy and labour, the regional business association, cluster initiatives, and the regional development agency. Firms were not directly involved. By soliciting the opinions of intermediary organizations such as chambers, associations or cluster initiatives, it was hoped that private-sector views would be filtered. Prioritization choices were defended vis-à-vis agents and firms on the basis of scientific evidence.

Nevertheless, the participatory process led to a certain diversity of opinions and to the negotiation of priorities. Consistent with the persistent trajectory taken, the objective was to define priorities in line with existing economic patterns and previous policies. When agents suggested to change or add priorities, organizers slightly rephrased priorities or, when adding another priority did not seem justified in terms of economic potential, chose not to include it and explained their choice. Still, the strategy features a low degree of selectivity but defines criteria for prioritizing policy support. When implementing the strategy, the regional development agency is bound to these criteria, thus ensuring a certain degree of selectivity in implementation.

Burgenland

Burgenland’s RIS3 was published in 2014. The strategy was developed in a participatory process encompassing public agencies, associations, higher education entities and a small number of firms, and led by a project team from a university of applied sciences. The strategy sketches the vision of transforming the regional economy into a knowledge-based society by strengthening education, knowledge, and creativity and by enhancing innovative links to neighbouring urban regions such as Vienna, Graz or Bratislava (University of Applied Sciences Burgenland, Citation2014).

Before 2014, the region did not have an innovation strategy and the provincial government was criticized for its passive stance on innovation policy. Owing to strong political support, the collective process that led up to the RIS3 was marked by enthusiasm on behalf of agents who participated in brainstorming sessions. The process suggests a disruptive trajectory. During the process, agents had the feeling that things were finally moving, and the successful adoption of an innovation strategy was seen as a milestone. In such an enthusiastic atmosphere, the danger of over-optimism in defining goals was countered with moderation by an expert who asked critical questions. For instance, when one agent proposed an unrealistic objective for start-up formation, the project team came up with evidence and engaged in negotiating a more realistic objective. Priorities were defined according to tangible economic potential. Thus, despite being suggested by agents, biotechnology was not included in the strategy’s priority areas.

However, after the adoption of the strategy, the political agenda changed. The body that was established to implement the strategy was merged into another entity, and the strategy’s implementation was downgraded on the political agenda. Remarkably, there was no outcry among most agents whose enthusiasm drove the collective policy-making process. Neither was there any collective attempt to rescue the strategy. Rather, it seems that agents returned to their previous narrative by criticizing the provincial government for its passive innovation policy.

Interpretation

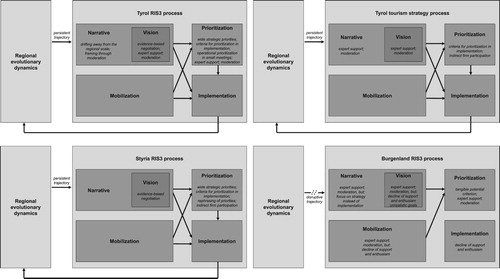

The collective regional policy-making processes in the three provinces can be analysed along the five stages and related behavioural challenges and concepts summarized in the framework proposed in .

Narrative

In Tyrol’s RIS3 and tourism strategy and in Burgenland’s RIS3, expert support served to take a view outside to the provincial government’s and other agents’ views, to come up with critical questions, and to engage in framing. Having a moderator who was an expert but knew the region proved useful but may have somewhat constrained possibilities to take an outside view from beyond the region. However, in Burgenland expert support and moderation did not prevent narrow framing since agents adopted a misguided narrative. The dominant frame adopted during the process apparently was that Burgenland needed an innovation strategy because other Austrian provinces had one, and the development club identified seems to have been the other eight provinces that had innovation strategies instead of structurally comparable regions in other countries. Consequently, the eventual RIS3 was seen as the ultimate objective instead of an instrument to be followed by implementation efforts to be able to achieve any impact.

Mobilization

No mobilization problems were evident in the prioritization or implementation stages in Tyrol and Styria which may be because of a long-standing cooperation culture and the role of strong intermediary organizations in indirect participation. No instance of blockade or open resistance because of loss aversion was evident which may be related to the wide and, hence, inclusive priorities adopted on the strategy level. Thus, there is a certain tension between mobilization and prioritization that calls for a trade-off or compromise.

The case of Burgenland illustrates mobilization problems in the implementation phase of the strategy that are related to a misguided narrative. Here, agents adopted a too narrow frame by focusing on the eventual existence of a strategy instead of the strategy’s implementation or eventual impact.

Vision

None of the cases provided an example for a backward-looking vision and lock-in. Over-optimism, in contrast, was addressed through evidence-based negotiations during the self-discovery process and through expert support and moderation. The four cases suggest that these strategies may be common. Still, the case of Burgenland demonstrates how over-optimism, in this case the uncritical assumption that political support and agents’ commitment to implementation would continue, can thwart the process.

Prioritization

In Tyrol’s and Styria’s RIS3 processes, delegating the task of more selective prioritization to the operative level explains the low degree of selectivity of the strategies, thus providing a possible solution to the behavioural problems inherent to selective prioritization such as the status-quo bias, loss aversion, or the endowment effect. Delegating selective prioritization is thus a compromise able to avoid mobilization problems or resistance because of loss aversion. Although evidence was used to ensure selective prioritization, it seems that this strategy did not preclude wide priorities in the two processes mentioned. Still, the narrower priorities defined in Burgenland’s RIS3 demonstrate that wide prioritization can be avoided when keeping the definition close to tangible economic potential.

Two strategies are employed to mitigate the risk of rent seeking: relying on expert support and moderation to ensure wide framing and indirect firm participation through intermediary organizations that act as a filter of opinions and thus serve to widen the frame of discussions.

Implementation

While there was no evidence of implementation problems in Tyrol and Styria, the case of Burgenland is illustrative. While mitigation strategies such as external moderation were employed, the fundamental problem of the decline of political support and agents’ enthusiasm was not solved. It seems plausible to assume that the enthusiasm during the collective process was over-optimistic and suffered from a planning fallacy because it was not sustained when the political agenda changed. During implementation, agents appear to have returned to their pre-RIS3 default option by not actively advocating for actual implementation. The narrow frame adopted by agents that the main achievement of the process would be the RIS3 itself contributed to the lacking focus on effective implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

summarizes the behaviourally based challenges encountered in the four collective policy-making processes and the mitigation strategies employed to overcome them. illustrates the behavioural insights for each case. In Tyrol and Styria, effective mitigation strategies bridged behavioural challenges and enabled generally successful strategy processes.Footnote2 Expert support and moderation seem to be adequate mitigation strategies against challenges related to narrow framing and overconfidence. Indirect firm participation is another strategy to counter rent seeking problems arising from narrow framing. Challenges in achieving selective prioritizations because of the status quo bias or loss aversion are confirmed in three of the four cases and are uniformly countered by delegating selective prioritization to the operative level. The use of evidence was apparently not sufficient to counter prioritization problems which may confirm the power of loss aversion. Sidestepping loss aversion through delegation thus seems to be a sensible compromise.

Figure 2. Collective regional policy-making processes in three Austrian provinces. Source: Author’s elaboration.

Table 2. Behaviourally based challenges and mitigation strategies in Tyrol, Styria and Burgenland.

The case of Burgenland illustrates how lacking mobilization for implementation thwarted the process. This lack of mobilization was related to the too narrow frame of focusing on the adoption of a strategy instead of its implementation and eventual impact. Further, over-optimism played a role because the decline of support and commitment was not anticipated. A ‘premortem’ (Klein, Citation2007, p. 18) exercise might have helped anticipating such a backlash. Including this or a similar exercise that serves to inject a fair dose of scepticism into the process thus seems desirable.

The results confirm the importance of objective evidence such as scientific studies and expert moderation in countering problems related to narratives, visions, and rent seeking (Grillitsch, Citation2016, p. 32). However, as the case of Burgenland demonstrates, behavioural problems because of narrow framing can thwart the process. In such a case, the role of place leadership (Sotarauta, Citation2018; Sotarauta & Beer, Citation2017) and political agency (Huggins & Thompson, Citation2019) can be crucial, both positively and negatively. Hence, adopting a wide frame that focuses not only on the policy-making process and resulting strategy itself but extends to implementation and eventual impact is critical. Although not surprising, this may be the most salient implication of the behavioural perspective for policy-makers embarking upon a collective policy-making process.

OUTLOOK

On the strategic level, more in-depth and comparative qualitative research could contribute to better understanding the behavioural side of agency in collective policy-making processes. While the case studies demonstrate the relevance of the framework proposed in this paper and hint at possibilities to mitigate human agency through external expertise, moderation, indirect participation, delegation of prioritization, and evidence, further research is necessary to understand behavioural aspects of regional policy. For instance, the behavioural side of lock-in should be further explored since the case studies did not yield insights here.

While this paper focused on the process of regional strategy design and on possibilities and constraints of mitigating human agency in collective policy-making processes, a behavioural perspective could be equally useful in better understanding the factors conditioning the effectiveness and efficiency of regional-policy implementation. For example, the role of conditionalities and incentives set by EU Cohesion Policy provides a wide field for applying and testing behavioural approaches (OECD, Citation2018). Research could elucidate how to design implementation procedures including fine-tuned details such as indicators or forms for project management and administration. For instance, how can operational procedures and reporting requirements be designed to focus on impact and efficiency while keeping the administrative burden for project managers low? The implementation of EU Cohesion Policy could strongly benefit from such a fine-tuned behavioural research agenda.

This paper’s interest in the behavioural side of policy-making processes can only be a first step towards such a research agenda. Further research on operational aspects of regional policy implementation will have to follow. Still, the research presented here on the strategic level of regional policy can help policy-makers and practitioners guide the upcoming wave of collective policy-making processes all across Europe for the new period of EU Cohesion Policy after 2020. Understanding how to design and apply mitigation strategies for behavioural problems is a highly relevant and pressing task, given the formidable challenges collective policy-making processes face. As the cases presented here demonstrate, even before confronting the manifold challenges of day-to-day implementation of regional policies, the very process of designing these policies is fraught with difficulties related to human behaviour and agency that threaten to thwart the process during its initial steps. Learning from other regions’ failure can help regional policy-makers and practitioners avoid common traps related to behaviour and agency. Such a focus on behaviour and agency could raise policy-makers’ and practitioners’ awareness for the importance of the set-up and management of the strategy design process and reduce the risk of putting too much attention on the strategy document at the expense of the process that leads up to the document. In addition, policy-makers and practitioners should keep in mind that the procedural challenges present during the strategy design process continue into the strategy implementation stage. This is why the pure existence of a strategy should not be seen as an objective in and of itself but merely as a milestone.

The insights gained from the Austrian cases suggest that cross-regional evaluations at the end of the current period of EU Cohesion Policy should evaluate not only the actual impact of project implementation as the ultimate objective of strategies but also the first procedural steps in Cohesion Policy on the regional level, that is, the process of initial strategy design. While processes will naturally differ between regions and while there can be no single ‘perfect’ type of process, the behavioural challenges identified in this paper will be relevant for most collective regional policy-making processes. Both the risks involved and the mitigation strategies tested by regions can equip policy-makers and practitioners with important knowledge on how benefit from experiences made under the recent wave of collective regional policy-making across European regions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The author thanks Neil Coe, Dimitrios Kyriakou and several reviewers for helpful comments. Further, the author is grateful to several anonymous interviewees for recommending further interviewees, and to all of them for participating in the interviews. The views expressed are purely those of the author and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission. Of course, all remaining errors are the author’s alone.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The author is grateful to an anonymous reviewer for drawing his attention to this point.

2 The evaluation of success refers only to the policy-making processes itself, but not to the impact of strategies that would need an impact evaluation after the end of the current EU Cohesion Policy financial period.

REFERENCES

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2000). Political losers as a barrier to economic development. American Economic Review, 90(2), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.2.126

- Alpert, M., & Raiffa, H. (1982). A progress report on the training of probability assessors. In D. Kahneman, P. Slovic, & A. Tversky (Eds.), Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases (pp. 294–305). Cambridge University Press.

- Austrian Conference on Spatial Planning. (2016). Policy framework for Smart Specialisation in Austria.

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2003). Toward a relational economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 3(2), 117–144. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/3.2.117

- Bathelt, H., & Glückler, J. (2014). Institutional change in economic geography. Progress in Human Geography, 38(3), 340–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513507823

- Becattini, G. (1991). Italian industrial districts: Problems and perspectives. International Journal of Management & Organization, 21(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1991.11656551

- Bell, D. E. (1982). Regret in decision making under uncertainty. Operations Research, 30(5), 961–981. https://doi.org/10.1287/opre.30.5.961

- Benner, M. (2014). From smart specialisation to smart experimentation: Building a new theoretical framework for regional policy of the European Union. Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie, 58(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw.2014.0003

- Benner, M. (2017). Smart specialization and cluster emergence: Building blocks for evolutionary regional policies. In R. Hassink & D. Fornahl (Eds.), The life cycle of clusters: A policy perspective (pp. 151–172). Elgar.

- Benner, M. (2019a). Overcoming overtourism in Europe: Towards an institutional–behavioral research agenda. In Zeitschrift für Wirtschaftsgeographie. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfw-2019-0016

- Benner, M. (2019b). Smart specialization and institutional context: The role of institutional discovery, change and leapfrogging. European Planning Studies, 27(9), 1791–1810. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1643826

- Benner, M. (2019c). The spatial evolution–institution link and its challenges for regional policy. European Planning Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1698520

- Capello, R., & Kroll, H. (2016). From theory to practice in smart specialization strategy: Emerging limits and possible future trajectories. European Planning Studies, 24(8), 1393–1406. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1156058

- Castells, M., & Hall, P. (1994). Technopoles of the world: The making of 21st century industrial complexes. Routledge.

- Cooke, P., Gomez Uranga, M., & Etxebarria, G. (1997). Regional innovation systems: Institutional and organisational dimensions. Research Policy, 26(4–5), 475–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(97)00025-5

- Fleming, D. (2001). Narrative leadership: Using the power of stories. Strategy & Leadership, 29(4), 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1108/sl.2001.26129dab.002

- Flyvberg, B. (2009). Survival of the unfittest: Why the worst infrastructure gets built – And what we can do about it. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 25(3), 344–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grp024

- Foray, D., David, P., & Hall, B. (2009). Smart specialisation – The concept. Knowledge Economists Policy Brief No. 9.

- Foray, D., Goddard, J., Goenaga Beldarrain, X., Landabaso, M., McCann, P., Morgan, K., Nauwelaers, C., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2012). Guide to research and innovation strategies for smart specialisation (RIS 3). Publications Office of the EU.

- Garretsen, H., Stoker, J. I., Soudis, D., Martin, R., & Rentfrow, J. (2019). The relevance of personality traits for urban economic growth: Making space for psychological factors. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(3), 541–565. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby025

- Gianelle, C., Guzzo, F., & Mieszkowski, K. (2019). Smart specialisation: What gets lost in translation from concept to practice? Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1607970

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties: The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm: On the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M. (2016). Institutions, Smart Specialisation dynamics and policy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614694

- Grillitsch, M., Asheim, B., & Trippl, M. (2018). Unrelated knowledge combinations: The unexplored potential for regional industrial path development. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 257–274. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy012

- Grillo, F. (2017). Structuring the entrepreneurial discovery process to promote private-public sector engagement. In D. Kyriakou, M. Palazuelos Martínez, I. Periáñez-Forte, & A. Rainoldi (Eds.), Governing smart specialisation (pp. 62–79). Routledge.

- Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.162.3859.1243

- Hassink, R., & Gong, H. (2019). Six critical questions about smart specialization. European Planning Studies, 27(10), 2049–2065. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1650898

- Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00124-X

- Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2019). The behavioural foundations of urban and regional development: Culture, psychology and agency. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(1), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx040

- Isaksen, A., Tödtling, F., & Trippl, M. (2018). Innovation policies for regional structural change: Combining actor-based and system-based strategies. In A. Isaksen, R. Martin, & M. Trippl (Eds.), New avenues for regional innovation systems: Theoretical advances, empirical cases and policy lessons (pp. 221–238). Springer.

- Juvan, E., & Dolnicar, S. (2014). The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 48, 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.05.012

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1984). Choices, values, and frames. American Psychologist, 39(4), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.39.4.341

- Kallbekken, S., & Sælen, H. (2013). ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Economics Letters, 119(3), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.03.019

- Karo, E., Kattel, R., & Cepilovs, A. (2017). Can smart specialization and entrepreneurial discovery be organized by the government? Lessons from Central and Eastern Europe. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 270–293). Elsevier.

- Klein, G. (2007). Performing a project premortem. Harvard Business Review, 85, 18–19.

- Knetsch, J. L. (1989). The endowment effect and evidence of nonreversible indifference curves. American Economic Review, 79, 1277–1284.

- Krueger, A. O. (1974). The political economy of the rent-seeking society. American Economic Review, 64, 291–230.

- Kyriakou, D. (2017). Avoiding EDP pitfalls: Exit, voice, and loyalty. In D. Kyriakou, M. Martínez Palazuelos, I. Periáñez-Forte, & A. Rainoldi (Eds.), Governing smart specialisation (pp. 20–33). London, New York: Routledge.

- Larwood, L., & Whittaker, W. (1977). Managerial myopia: Self-serving biases in organizational planning. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62(2), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.62.2.194

- Lee, N. D. (2017). Psychology and the geography of innovation. Economic Geography, 93(2), 106–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2016.1249845

- Loewenstein, G. (1988). Frames of mind in intertemporal choice. Management Science, 34(2), 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.34.2.200

- Loewenstein, G., O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2003). Projection bias in predicting future utility. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1209–1248. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552784

- Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1982). Regret theory: An alternative theory of rational choice under uncertainty. The Economic Journal, 92(368), 805–824. https://doi.org/10.2307/2232669

- Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (1986). Disappointment and dynamic consistency in choice under uncertainty. The Review of Economic Studies, 53(2), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297651

- Lourenço, J. S., Ciriolo, E., Rafael Almeida, S., & Troussard, X. (2016). Behavioural insights applied to policy: European report 2016. Publications Office of the EU.

- Martínez-López, D., & Palazuelos-Martínez, M. (2015). Breaking with the past in smart specialisation: A new model of selection of business stakeholders within the entrepreneurial process of discovery. Journal of Knowledge Economy, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0234-3

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European Union Cohesion Policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Morgan, K. (2007). The learning region: Institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional Studies, 41(sup1), S147–S159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701232322

- Obschonka, M., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., Silbereisen, R. K., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2013). The regional distribution and correlates of an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom: A socioecological perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032275

- Odean, T. (1998). Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? The Journal of Finance, 53(5), 1775–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00072

- OECD. (2017). Behavioural insights and public policy: Lessons from around the world.

- OECD. (2018). Rethinking regional development policy-making.

- Oughton, C., Landabaso, M., & Morgan, K. (2002). The regional innovation paradox: Innovation policy and industrial policy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 27(1), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013104805703

- Payne, J. W., Laughhunn, D. J., & Crum, R. (1980). Translation of gambles and aspiration level effects in risky choice behavior. Management Science, 26(10), 1039–1060. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.26.10.1039

- Phillimore, J., & Joseph, R. (2003). Science parks: A triumph of hype over experience? In L. V. Shavinina (Ed.), International handbook on innovation (pp. 750–757). Amsterdam: Pergamon.

- Province of Tyrol, Tirol Werbung, Tyrol Chamber of Economy and Federation of Tourism Associations. (2015). Der Tiroler Weg 2021: Kernbotschaft einer Strategie für den Tiroler Tourismus. Retrieved December 26, 2019 from https://www.tirolwerbung.at/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/strategie_tiroler_weg-(2021.pdf

- Provincial Government of Styria. (2016). Wirtschafts- und Tourismusstrategie Steiermark 2025: Wachstum durch Innovation. Retrieved December 26, 2019 from http://www.wirtschaft.steiermark.at/cms/dokumente/10430090_12858597/b89a9de2/Wirtschafts-%20und%20Tourismusstrategie_03062016.pdf

- Provincial Government of Tyrol. (2013). Tiroler Forschungs- und Innovationsstrategie. Retrieved December 26, 2019 from https://www.tirol.gv.at/fileadmin/themen/arbeit-wirtschaft/wirtschaft-und-arbeit/downloads/Tiroler_Forschungs-_und_Innovationsstrategie.pdf

- Radosevic, S. (2017). Assessing EU smart specialization policy in a comparative perspective. In S. Radosevic, A. Curaj, R. Gheorgiu, L. Andreescu, & I. Wage (Eds.), Advances in the theory and practice of smart specialization (pp. 2–37). Elsevier.

- Rentfrow, P. J., Jokela, M., & Lamb, M. E. (2015). Regional personality differences in Great Britain. PloS One, 10(3), Article e0122245. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122245

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Hardy, D. (2014). Technology and industrial parks in emerging countries: Panacea or pipedream? Springer.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2006). Better rules or stronger communities? On the social foundations of institutional change and its economic effects. Economic Geography, 82(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2006.tb00286.x

- Samuelson, W., & Zeckhauser, R. (1988). Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 1(1), 7–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00055564

- Saxenian, A. L. (1994). Regional advantage: Culture and competition in Silicon Valley and route 128. Harvard University Press.

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (1985). The disposition to sell winners too early and ride losers too long: Theory and evidence. The Journal of Finance, 40(3), 777–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1985.tb05002.x

- Simon, H. A. (1982). Models of bounded rationality. MIT Press.

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Sotarauta, M., & Beer, A. (2017). Governance, agency and place leadership: Lessons from a cross-national analysis. Regional Studies, 51(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1119265

- Storper, M. (1995). The resurgence of regional economics, ten years later: The region as a nexus of untraded interdependencies. European Urban and Regional Studies, 2(3), 191–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/096977649500200301

- Storper, M. (1997). The regional world: Territorial development in a global economy. Guilford.

- Storper, M., Kemeny, T., Makarem, N., & Osman, T. (2015). The rise and fall of urban economies: Lessons from San Francisco and Los Angeles. Stanford University Press.

- Thaler, R. H. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(80)90051-7

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- Trippl, M., Zukauskaite, E., & Healy, A. (2019). Shaping smart specialization: The role of place-specific factors in advanced, intermediate and less-developed European regions. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1582763

- Troussard, X., & van Bavel, R. (2018). How can behavioural insights be used to improve EU policy? Intereconomics, 53(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10272-018-0711-1

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1981). The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice. Science, 211(4481), 453–458. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.7455683

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1991). Loss aversion in riskless choice: A reference-dependent model. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 1039–1061. https://doi.org/10.2307/2937956

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00122574

- University of Applied Sciences Burgenland. (2014). FTI-Strategie Burgenland 2025. Retrieved December 26, 2019 from https://rio.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en/file/10923/download?token=DBM2X_pg