ABSTRACT

This paper contributes to the growing body of literature aimed at understanding the wide-ranging implications of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) by displaying the variety of contractual, formal and informal arrangements that China has entered with European states on a bilateral basis. Almost all European states have entered into one or another form of formal cooperation under the disguise of the BRI. In general, Eastern European states tend to have the highest degree of formal cooperation as official BRI members, whereas the picture is more diverse in the North-West of Europe. Cooperation ranges from investment-based infrastructure projects to joint financial investments, as well as projects in education or health. This complicated puzzle of arrangements ultimately favours China’s influence and will change Europe’s interconnectedness with China beyond transport connectivity.

In 2013, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a major undertaking, named initially as the One Belt and One Road Initiative and later referred to as Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), to support better connectivity of the Asian, European and African continents. Often referred to as the ‘New Silk Road’, the BRI revives the idea of the ancient Silk Road, which describes traditional trading routes spanning across China, the Asian continent, the Middle East and Europe (Zhou et al., Citation2019). Speaking at the University of Astana in Kazakhstan in 2013, Jinping suggested that ‘[to] forge closer economic ties, deepen cooperation and expand development space in the Eurasian region we should take an innovative approach and jointly build an “economic belt along the Silk Road”’ (cited in Brakman et al., Citation2019, p. 3).

The BRI consists of the Silk Road Economic Belt, which (in its core) is a combination of six corridors across land,Footnote1 and the 21st-century Maritime Belt (see Figure S2 in the supplemental data online). Further, China’s Arctic Policy sets out the ambition to develop a Polar Silk Road, which would connect to Europe via the North Sea (Bennett, Citation2016; SCIOPRC, Citation2018; Zhan, Citation2020). It is these corridors in which China focuses its investments and cooperation with states to increase infrastructure connectivity and economic activity via a diversity of projects. The BRI is, hence, not a single megaproject but a continuously growing initiative with a large portfolio of projects for (1) rail, road, sea and airport infrastructure, (2) power and water infrastructure, (3) real estate contracts and, more recently, (4) digital infrastructure. For these projects to be realized, the BRI builds on an increasing institutionalized, contractual and structured cooperation between China and other states.

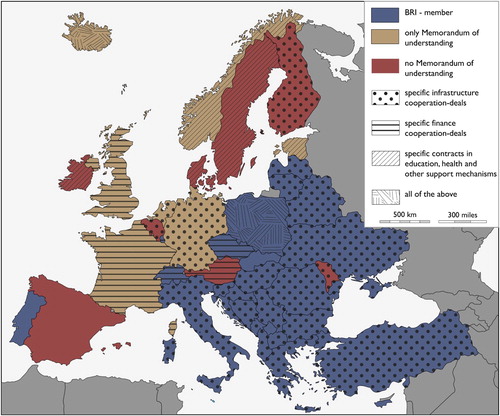

The research provides a comprehensive overview of the influence the BRI already has in Europe, and the diversity of these bilateral relationships. The regional graphic () illustrates these bilateral contractual arrangements and informal or formal agreements between China and European states. Therefore, it sheds a light on the influence of the BRI in Europe beyond individual projects and geopolitical debates (Maçães, Citation2018) often in the focus of the public eye. The BRI reflects China’s global power as much as it represents China’s attempts to solidify relations with countries (Liu & Dunford, Citation2016), and, as we argue here, it presents a grand strategy based on an incremental rise of overlapping contractual arrangements, cooperations and memberships.

Figure 1. Contractual arrangements and other informal or formal agreements, March 2020.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration. Source of base map: (https://d-maps.com/carte.php?num_car=2233&lang=en).

The information was collected through desk research between January 2019 and March 2020 of each state’s governmental webpages as well as communications and publications of European institutions (e.g., European Commission, Citation2019; European Parliament, Citation2018).

illustrates, first, the complexity of contractual arrangements that China has sought on a bilateral basis with European states to date (for a detailed description, see in the supplemental data online). Instead of seeking a ‘block-based’ approach with the whole of Europe, China develops multiple arrangements and memorandums of understanding, resulting in a certain east–west divide, with more Eastern European countries being BRI members. This can partly be explained by joint historic roots as well as by the entry points of the BRI to Europe (see Figure S2 in the supplemental data online).

Second, illustrates the constructive fuzziness of the Chinese approach with a focus on topics that are in the interest of individual states. Newspaper articles often display the fear that the BRI with its geopolitical ambitions may undermine ‘European integrity’. While the calls for a joined-up European response are increasing, shows that formal arrangements are already far more common than publicly recognized. This complicated puzzle of bilateral arrangements ultimately favours a hidden growth of Chinese continuous influence in Europe.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Faculty of Spatial Planning of TU Dortmund for funding the mini-project ‘Towards an Asianisation of European Cooperation and Planning? – Evidence from the Belt and Road Initiative’ while Franziska Sielker was Interim Head of the Chair of International Planning Studies. This paper partly builds on research undertaken in the context of this mini-project. The authors also thank the Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge, for funding a research visit of Elisabeth Kaufmann in March 2020.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (831.1 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 For further information on the six economic corridors see: (1) The New Eurasia Land Bridge (NELB), also known as the Second Eurasia Land Bridge at https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/; (2) China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) at http://cpec.gov.pk/; (3) China–Mongolia–Russia Economic Corridor at https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/; (4) China–Central Asia and West Asia Economic Corridor (CCWAEC) at https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/; (5) China–Indochina Peninsula Economic Corridor (CICPEC) at https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/; and (6) Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar Economic Corridor at https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/.

REFERENCES

- Bennett, M. M. (2016). The Silk Road goes north: Russia’s role within China’s belt and road initiative. Area Development and Policy, 1(3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1239508

- Brakman, S., Frankopan, P., Harry, G., & Van Marrewijk, C. (2019). The New Silk Roads: An introduction to China’s belt and road initiative. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy037

- European Commission. (2019). China: Challenges and prospects from an industrial and innovation powerhouse. https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/china-challenges-and-prospects-industrial-and-innovation-powerhouse

- European Parliament. (2018). Research for TRAN committee: The new Silk Route – Opportunities and challenges for EU transport, p. 100. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/585907/IPOL_STU(2018)585907_EN.pdf

- Liu, W., & Dunford, M. (2016). Inclusive globalization: Unpacking China’s belt and road initiative. Area Development and Policy, 1(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1232598

- Maçães, B. (2018). Belt and road: A Chinese world order. Hurst.

- SCIOPRC (State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China). (2018). China’s arctic policy. http://english.www.gov.cn/archive/white_paper/2018/01/26/content_281476026660336.htm

- Zhan, C. (2020). China’s ‘arctic silk road’. In Maritime Executive. https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/china-s-arctic-silk-road

- Zhou, J., Yang, Y., & Webster, C. (2019). Legacies of European ‘belt and road’? Visualizing transport accessibility and its impacts on population distribution, regional studies. Regional Science, 6(1), 451–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1652111