ABSTRACT

Creativity is one of the factors promoting the development of urban centres. Its significance provokes discussion on issues such as the creative city, creative industries and creative clusters, and it contributes to the increased demand for multidisciplinary research on economic, social and artistic policy. The paper is devoted to creative industries clusters located in Poland. Its main goal is to identify the factors that hinder the operation of the analysed clusters. The observed factors are broken down into endogenous and exogenous ones, as well as into those that emerged during cluster mobilization and others which surfaced later during the clusters’ existence. The survey was conducted among creative cluster coordinators, using computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) and computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI). The results show that most of the problems mentioned by respondents are internal factors, of which the most important one is a misunderstanding of the idea of clustering and the resulting reluctance to share knowledge, as well as the dominance of competition over cooperation, frowned-upon movements of employees between cluster participants, and the consequent diminished trust. External barriers were revealed mainly in further periods of the clusters’ operation. The most important of them was a dependence on external funding. Respondents pointed to a lack of interest on the part of local government units, which makes it difficult to build a properly functioning triple helix. It should also be added that cluster policy in Poland has been moving away from clusters understood in geographical terms where spatial concentration and economic specialization were the key features. Currently, cluster policy is directed more towards managing cluster structures.

INTRODUCTION

The undiminished interest in cluster structures is a result of the increased significance of the local level and of endogenous potential, as well as of the growing importance of the accumulation of human capital and accelerated technological growth. An effective cluster boosts the productivity of local businesses (Mariussen, Citation2001) as well as increasing the number of new businesses (Sternberg, Citation2001), which translates into new jobs. The geographical proximity of businesses is expected to stimulate and support their innovation. Clusters are created in all sectors of the economy. They can be found both in heavy industry and in services, in high-tech and in traditional sectors. They also adopt various strategies and follow various directions and opportunities for growth.

The paper is devoted to creative industries clusters located in Poland. In the last few years, the number of this type of clusters has decreased. However, there are still 18 of them (12 active and six suspended), which means that apart from networks and strategic alliances, they still represent an interesting and not fully utilized model of cooperation between entities. Besides, creative industries are an important part of the economy, and they should be treated more broadly, not only as a sphere reserved for the world of art but also as a field tied to other economy sectors. However, despite the significance of cluster structures and of creative industries, only a few studies have addressed their specific problems. Among such unaddressed topics are the impact of creative clusters on the labour market or the analysis of factors hindering functioning. The main purpose of this paper was to take a closer look at one of the key problems, namely the factors hindering the functioning of creative clusters. The following questions were posited:

• Are the barriers to the development of creative clusters endogenous or exogenous in nature?

• Were they already known at the initial stage of cluster operation?

• Were they hard to foresee and appeared only at a further stage of cluster existence?

The conclusions derive from surveys – computer-assisted web interview (CAWI) and computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) – conducted in 2019 among creative cluster coordinators in Poland. The research hypothesis assumes that the barriers to the development of creative clusters in Poland are primarily exogeneous in nature, that is, they arise outside the cluster structures or at the interface between the cluster and its surroundings. The problem of barriers to the development of creative clusters in Poland has not yet been present in the literature of the subject.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section is devoted to the concept of industrial clusters, including creative clusters, in the literature on the subject. The third section provides basic information about clusters in Poland. The final section concludes.

THE CONCEPT OF INDUSTRIAL CLUSTERS, INCLUDING CREATIVE CLUSTERS, IN THE LITERATURE ON THE SUBJECT

M. E. Porter is regarded as the seminal figure of contemporary cluster research (cf. Porter, Citation1998). In his work from the 1990s, Porter describes clusters as geographical concentrations of interconnected companies, specialized suppliers, firms in related industries and associated institutions (e.g., universities and trade associations) that compete but also cooperate. Porter’s definition remains the best known. However, over almost 30 years, new concepts have emerged highlighting or questioning the above-mentioned cluster characteristics. Some approaches clearly highlight the importance of links between entities. For example, Piore (Citation1990) defines a cluster as a network of interorganizational relationships, while Gupta and Subramanian (Citation2008), Rosenfeld (Citation1997), Chapain and Comunian (Citation2010) and Hassink (Citation2005) argue that the essence of a cluster is access to information and joint learning to enable knowledge flow between participants. In turn, the geographical proximity promoting the creation of bonds of complementarity was emphasized in the work of, among others, Gordon and McCann (Citation2000) and De Berranger and Meldrum (Citation2000). However, according to some authors, such as Martin and Sunley (Citation2003) as well as Den Hertog and Maltha (Citation1999), participant location should not be overestimated when predicting the chances for a cluster’s success.

In fact, there are two concepts used in regional policy: cluster and cluster initiative (cf. Kowalski & Marcinkowski, Citation2014; Morgulis-Yakushev & Sölvell, Citation2017). The cluster initiative is a cluster-based instrument of development policy. It is a formalized forum aimed at promoting the growth and increasing competitiveness of a cluster. The actions taken by the cluster coordinator are of great importance in this respect. In general, cluster initiatives serve the development of clusters so that they can achieve sufficient critical mass, establish intensive interactions, and high levels of competitiveness and innovation. The above distinction between cluster and cluster initiative is not always articulated in publications. However, some studies, including the present one, are actually concerned with cluster initiatives.

According to Child et al. (Citation2005), the creation of a cluster leads to several benefits and enables the reduction of the emerging problems such as uncertainty about survival in the market, lack of trust in other participants or problems with the relocation of resources. In addition, it creates a stronger link between cluster members and scientific institutions, enabling an exchange of knowledge and the utilization of innovative solutions. The above range of achievable benefits and the elimination of potential problems are the reason why clusters are set up in various countries and across different industries. As a result, there arises a need to identify cluster structures and to monitor their operation.

Clusters are also formed by entities engaged with creative industries. Creative industries are activities based on intellectual property, rooted in culture and science, and having the potential to create added value and jobs. They include advertising, publishing, photography, architecture, radio and television, film and video, music, design (among others interior design, industrial design, multimedia and fashion design), performing and visual arts, crafts, video and computer games as well as the activity of museums, galleries and libraries (Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Citation2013). Creative industries stand out from other activities. They consist of many small enterprises with uncertain market position, with low-technology innovation, and engaged in cooperation that is less formalized than in other sectors. Also, creative industries are sometimes regarded as ‘unproductive’ and ‘unnecessary’ compared with other larger economy sectors. A characteristic feature of this sector is buzz and its significance for the segment’s development (Banks & O’Connor, Citation2017; Florida, Citation2002; Gong & Xin, Citation2019; Hartley et al., Citation2013; Landry, Citation2000; O’Connor, Citation2015). Creative clusters are formed primarily by various creative groups, including cultural institutions, entities involved in broadly understood artistic and entertainment activities, as well as by private entities engaged in advertising, publishing, etc. The participation of entities responsible for commercialization is increasingly frequent, with their duties including the promotion of events and products, distribution or organization. Venture capital organizations participating in the financing of innovative projects also play a role, which is significant due to the fact that creative industries are still associated with medium and high-level risk (Banks et al., Citation2000; Gibson & Kong, Citation2005). Clusters of this kind can also operate at the interface of different areas, such as creative activities and the processing industry (cf. Comunian & England, Citation2019). Creative clusters are mostly established in metropolitan areas. For example, according to Boix et al. (Citation2015), as many as 75% of such clusters in the European Union (EU) are established in metropolitan areas. In these areas, clusters downright overlap, sharing common space, which further enhances the positive impact of synergies (Boix et al., Citation2016). Also Bereitschaft (Citation2014), Florida et al. (Citation2010) and Heebels and van Aalst (Citation2010) observed a shift from regional clusters towards urban centre clusters that offer a large market for creative industries as well as the presence of leading cultural institutions.

Research on creative clusters was also carried out in Poland. For example, Środa-Murawska and Szymańska (Citation2013) analysed the geographical concentration of creative entities using the location quotient (LQ), identifying areas that offer favourable conditions for setting up clusters (Środa-Murawska & Szymańska, Citation2013) and yet whose potential is not fully utilized (latent clusters). Ratalewska (Citation2016) described the increase in the importance of culture and opportunities for the development of creative industries in Poland compared with the EU. In turn, Jankowska and Götz (Citation2017) studied the internationalization of clusters on the example of creative clusters (cf. Jankowska & Götz, Citation2017). Among papers devoted to creative clusters in Central and Eastern Europe is that by Bialic-Davendra et al. (Citation2016) dealing with the condition and operating strategy of creative clusters. As Bontje et al. (Citation2011) and Marková (Citation2014) have demonstrated, the specificity of Central and Eastern Europe lies in the fact that creative clusters operating here depend on financial assistance from operational programmes (OP). The problem of top-down control of cluster policy was also mentioned by Mizzau and Montanari (Citation2008), who showed that a bottom-up approach in clustering is more effective than top-down control, and that top-down policy in this regard can lead to a waste of public funds.

CLUSTERS IN POLAND

The main entity responsible in Poland for the implementation of cluster policy at the central level is the Ministry of Development, which understands cluster policy as a part of coherent public policies, including education policy, industrial policy, technological policy and innovation policy. Currently, a focus is placed on clusters that are significant for the country’s economy and which are characterized by high international competitiveness (Ministry of Development, Citation2020).

Until 2012, a constant growth in the total number of clusters in Poland was observed. However, the trend has recently reversed, and the number of clusters is gradually decreasing. According to a 2015 study by the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development, there were 134 active clusters, the first of which was established in 2003, but a majority (> 60%) are new ones initiated after 2011. The biggest number of clusters was identified in the information and communication technology (ICT) sector, power engineering, the construction industry and in the medical sector. A significant number of clusters can also be found in the metal industry, tourist sector and business services sector (Podgórska, Citation2016). In 2003, the European Commission noted that Poland has not developed or implemented a cluster-based development policy. As a consequence, considerable funds were spent in the following years to change that fact. The possibility of co-financing under the OP in 2007–13 was a breakthrough in this respect. It was during this period that cluster-based policy (with clustering as a key condition for increasing competitiveness) became very popular. Overall, in 2011–13, Poland saw an increase in the number of newly established clusters, some of which were naturally formed relying on the existing resources while others were artificial structures. However, the foundations on which the clusters were built did not pass the test of time and after the end of EU funding some of the clusters, having failed to develop their own independent mechanisms of survival on the market, went out of business. In general, a majority of the existing clusters are young structures whose short history has not yet allowed them to achieve the expected results. Therefore, the number of clusters that are mature, booming and growing is relatively small. In this situation, in 2015, the Ministry of Development decided to select key national clusters (KNC). The decision coincided with the implementation of the Europe 2020 strategy and with the concept of Smart Specialisations proposed by the European Commission, which assumes the concentration of efforts and resources on a specified number of priorities and economic specializations. Clusters wishing to obtain the KNC status had to demonstrate above all their innovative quality and international value chain. Currently (the status is awarded periodically) there are 15 KNCs in Poland, which represent such sectors as ICT (three), transport (two), automotive (two) and aviation industry (two). The group does not include any creative clusters.

In the case of creative clusters, the entities making up the cluster represent creative industries or other related sectors. Clusters of this kind are rather small compared with ICT or biotechnology clusters. They are created in a less formalized environment with a lower technology component. In addition, they are characterized by a small impact on the labour market and by several factors hindering their operation. The latter problem is the main theme of this paper. The literature on the subject (cf. Hołub-Iwan & Wielec, Citation2014; Podgórska, Citation2016) lists several factors that generally hinder the functioning of cluster structures in Poland. They include the small importance of the cluster, the reluctance to share business and technological know-how, and the lack of external sources of funding. The present study sought to investigate the extent to which these factors are actually perceived as barriers to cluster operation. It also pondered whether they are really the only factors inhibiting the development of clusters in Poland.

DIRECT EXAMINATION OF CLUSTERS IN POLAND

Purpose and research method

The aim of the research was to identify factors hindering the functioning of creative clusters in Poland. The study sought to establish the nature of these factors and to answer the question of whether they are endogenous determinants arising within the structure of the cluster itself or rather exogenous factors beyond the control of the clusters.

The assessment of the barriers to the development of creative clusters was a part of a larger study. The questionnaire included questions concerning the change in the number of cluster participants, the structure of the cluster, its reach and its changes. Also investigated were the links within the cluster as well those between the cluster and the external environment. Other questions concerned the motives for clustering, the importance of the distance between entities, the deployments and patents created, and the relationship between competition and collaboration within the cluster.

The first stage of the study used the CAWI method. The question about development barriers included the five-point Likert ordinal scale. The responses included in the survey (nine options) were chosen based on the literature on cluster structures in Poland (see above). However, room for additional responses and comments was provided. It turned out that the coordinators added new, numerous barriers, as well as shared their insights about the issue under investigation. The above prompted the author to conduct a second phase of the study in which information was gathered through an individual in-depth interview (CATI). The interview was conducted according to the diagram shown in . The coordinators were free to provide any number of factors they considered as hindering the functioning of the cluster, broken down into internal and external. Barriers mentioned by at least three coordinators were highlighted.

The questions were answered by cluster coordinators. The role of coordinator is usually performed by the entrepreneur who was usually the initiator of the cluster initiative. Among others, the coordinator is responsible for drafting the cluster development strategy, preparing the project management methodology, managing conflicts of interest, as well as the definition of the cluster’s offering and promotion.

Both stages of the study were conducted between December 2018 and June 2019. The scope of the study was all creative clusters located in Poland. Based on the available sources, it was established that at the time of the study there were 18 creative clusters (active or temporarily suspended) in Poland. Out of this group, 17 creative cluster coordinators were enrolled in the study. For 12 of them, creative industries were the core or the only type of business activity. For five of the respondents, creative industries were a secondary activity; in such clusters core activities included printing, tourism or the ICT sector ().

Table 1. Creative clusters participating in the study (in alphabetical order).

The analysed clusters were established in 2006–15, with the biggest amount created in 2011–12. The current number of entities in the investigated clusters ranges from four to 95, and in 10 of them it was systematically growing until it reached the current value. The author tried to establish if there was a correlation between the duration of the cluster’s market presence and the number of its members. Therefore, Kendall’s tau coefficient, which is a measure used to study the relationships between columns of ranked data, was calculated. The score of 0.195 (on a scale of −1 to 1) was obtained, which means that there is no monotonic relationship between the analysed variables. Therefore, there is no relationship between the number of cluster members and the number of years of its market presence. The survey has shown that 14 out of 17 analysed creative clusters are examples of Marshallian clusters composed of small companies engaged in the same or similar activity rooted in local capabilities (Markusen, Citation1996). In addition, one hub-and-spoke cluster was identified, with a network of smaller entities anchored around one dominant entity and two state-anchored clusters around public institutions (universities). Design and advertising were the activities indicated by most respondents. All the analysed clusters are shown in and identified by location of the cluster’s head office. The biggest number of clusters (as many as seven in the analysed group) are located in Upper Silesia (Śląskie province). There are no more than two creative clusters in the remaining provinces.

RESULTS

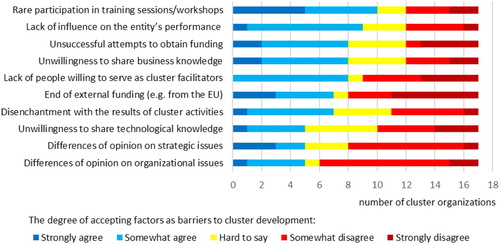

The first results regarding the factors hindering cluster operation were determined during the CAWI survey. Member passivity measured by their low involvement in cluster activity and the weak influence of the cluster on the position of its participants were the biggest barriers to development mentioned by the respondents. The use of external funds was been mentioned. The lack of external funding proved to be another significant barrier for the investigated clusters. In addition, the coordinators cited the lack of persons willing to serve as cluster coordinators and the reluctance to share business knowledge. However, the above results turned out to be insufficient. The coordinators had added a large number of other factors not included in the questions and not mentioned in the literature of the subject. Therefore, it was decided to examine the problem more closely by conducting one-on-one interviews with the coordinators of the examined clusters ().

Figure 2. Factors hindering the functioning of creative clusters in Poland: results of a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) survey.

Source: Author’s own study.

Interviews with the coordinators of the analysed clusters enabled to identify the factors that, in the opinion of the coordinators, hinder cluster development. These factors were grouped depending on whether they were endogenous (arising within the structure of the cluster itself) or exogenous (beyond the control of the clusters) and if they appeared already in the phase of cluster mobilization or in the later period of its functioning. The above dichotomous division of factors on the basis of two features (time of emergence and place of origin) made it possible to divide the above-mentioned barriers to development into four groups ().

Table 2. Factors hindering the functioning of creative clusters in Poland: results of a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) survey.a

A general observation was that the number of internal factors mentioned by the respondents exceeded the number of external factors. Therefore, a majority of the barriers arose in the clusters themselves and often resulted from the lack of experience in the formation and management of such structures. The most frequently indicated factor (excessive number of entities in the cluster) was a result of adjusting to the method of the distribution of funds under the OP adopted by regional level government entities. The principle was that clusters received points for the number of its members, as well as one point for each research and development (R&D) unit. With the aim of obtaining funding, the clusters were willing to accept new members to reach critical mass. However, it quickly turned out that the definition of a common strategy in such a large group is difficult due to the emerging conflict of interest. Later on, other problems appeared, such as only the occasional interest of members in the cluster’s activities or the absence of decision-makers when important joint arrangements needed to be made. There were also disagreements resulting from the too general wording of partnership agreements or similar documents, for example, regarding the identification of the cluster in geographical and functional terms, the precise definition of its economic specialization or the relationships typical for a triple helix. Thus, ultimately, the criterion of the number of entities in the cluster did not prove to be useful. In the opinion of the coordinators, the methodology for cluster monitoring practiced by the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development was better thought-over. The agency deals with cluster policy at the central level, and its methodology is based on the importance of the value chain within the cluster and not on the number of its members. However, in practice, co-financing from the central level based on such a methodology turned out to be very difficult to obtain.

The investigated clusters generally included micro- and small enterprises. In terms of number, the prevailing type were microenterprises that treated their presence in the cluster as helpful at the initial stage of activity. These entities counted more on business contracts than on the exchange of knowledge. They were not willing to share ideas, which was largely due to mental barriers. They were mainly focused on the profit in the operational perspective of one year hoped to be generated by the side of a larger, more reputable player than on thinking in terms of a long-term development strategy involving technology exchanges. Foundations and associations, which by definition are based on cooperation, turned out to be most willing to cooperate. They act quickly and are often driven by values greater than profit measured by the power of money. In turn, large enterprises rarely join clusters in Poland, especially those clusters that rely on external financing. The above is the effect of clustering policy according to which support is intended only for micro- and small enterprises. Large enterprises need to finance their activities within the cluster themselves because the cluster cannot include such entities in its accounting process or in the activity report. On the other hand, entities with mixed capital or those created solely on the basis of foreign capital cannot be beneficiaries of state aid in the resident country (although subsidiaries may benefit from such aid). Problems also appeared during cooperation between entrepreneurs and universities. It turned out that the institutional character of the university is not the best fit for business, which relies on taking advantage of opportunities and requires immediate responses and risk-taking. Intellectual property-related problems appeared, for example, in a situation where a patent developed by an R&D unit was funded by business.Footnote1

Having a cluster coordinator turned out to be important. The role of a coordinator can be played by a non-profit entity (association or company) that becomes a party to the consortium agreement or a supporting partner in a cooperation agreement. Where a cluster had a leader, the lack of the cluster’s legal status was not a problem. However, for clusters without a leader, the lack of legal personality became a hindrance because the cluster could not become a beneficiary of funding.

Other problems concerned the financing of cluster activities. The smallest number of the financing problems was reported by clusters that have not become dependent on external funding and developed their own mechanisms of functioning which enabled their uninterrupted operation. On the other hand, clusters that relied on co-financing (as many as 11 out of 17 coordinators indicated the possibility of using external funds, mainly from the EU, as the main motivation of cluster formation) experienced significant problems. In 2007–13, the European Commission decided to allocate significant resources to cluster policy (e.g., measures 5.1 OP Innovative Economy and 1.6 OP Supporting the creation and expansion of advanced production capabilities and service development). However, the new perspective 2014–20 contains virtually no funds allocated strictly for cluster policy. An exception to the above is the selection and support for KNC which could benefit mainly from the OP KED (Operational Programme Knowledge Education Development) to finance their expenses on education and vocational training. Therefore, EU funds as a source of (co-)financing were more important in 2007–13. Nevertheless, even then problems were still present – at first with the accumulation of an own contribution (despite the fact that co-financing could be as high as 85%) and later with the management of EU funds when some clusters wanted to replace the funding of soft costs (seminars, research, workshops) with funding of hard costs (offices, equipment, software). Another problem was the lack of regulations regarding the acquired technical infrastructure, including the provision that the coordinator cannot generate an income and has a duty to share the purchased goods and must also ensure sustainability of the project for five years after its termination (including office space, administration, website).

The coordinators also expressed their views on the idea of clustering in general. For example, some said that the Polish economy is not yet ripe for coopetition and that companies prefer to act on their own because they do not trust each other. Activities such as the flow of employees between companies in the cluster (which is an element of the so-called tacit knowledge) or copying the offer of another entity were not welcome and regarded as activities hindering the development of a real partnership.

In addition, the coordinators complained about ambiguities in copyright law concerning, among others, the above-mentioned patents. Some respondents also stated that to thrive, creative industries should receive dedicated support. And such forms of support, especially for art and culture, are non-existent in Poland. The respondents also pointed out that when comparing clusters, the same criteria are applied for culture as for industry or broadly understood business. As a consequence, clusters involved in the cultural sector usually fare poorly in such comparisons, as they do not score highly in ‘new technologies’. The few exceptions include clusters engaged in design and industry, with such a combination offering a valuable implementation potential. For example, in the surveyed group, only one cluster introduced new industrial designs and another a new technology in the field of multimedia and information technology.

Clusters may bring an important contribution to the building of economic specialization of regions, for example, in the sector of film production or creative industries in general, which may have some impact on the image of cluster structures in the future. However, despite the potential impact of clusters on the region’s specialization, there was a lack of interest in this type of structures observed on the part of the local government. In turn, the attention of the central authorities is focused on KNC. Bearing in mind the above-mentioned factors, some of the coordinators were quite pessimistic about the future (eight responses). They would say, for example, that the cluster structure is unnecessary because the goals that the companies have decided to implement jointly are already implemented or will be implemented in future outside the cluster and the cluster structure is not indispensable to achieving it.Footnote2

It is worth noting that none of the responses mentioned the questionable issue of spatial concentration discussed in the literature. The above was the case despite the fact that the surveyed structures included both clusters located in one city, in one region (province) and spanning several regions. The interviews have shown that distance in space is not a factor hindering the functioning of creative clusters in Poland. Also, other responses concerning the flow of knowledge, technology and organization of meetings/workshops/courses do not allow a conclusion to be made that the intensity of connections depends in any way on the geographical distance between entities. Only one factor mentioned by the respondents was related to location in space. One the respondent observed that the majority of the most competitive film industry entities are located in Warsaw. Therefore, a cluster established away from the capital city, in a completely different region, had problems with the participation in and management of film-related projects, despite the fact that it had the required capabilities.

CONCLUSIONS

In the last few years, the number of industrial clusters in Poland has decreased. However, there are still more than 130 of them, including 18 creative industrial clusters. The study aimed to determine the factors hindering the functioning of clusters with the example of creative clusters in Poland. The collected data offer a rather complex picture of the mentioned barriers to development. First, it should be stated that the majority of the listed problems are internal factors arising in the cluster itself. Some of them emerged already in the initial period of the cluster’s activity and included problems such as a conflict of interest revealed during the development of the cluster’s strategy. The large number of entities in the cluster also turned out to be a problem. Even more problems appeared in the subsequent stages of the cluster’s development. Among others, they included disagreements resulting from the provisions of the partnership agreement being too general. The acquisition of external funding and the co-financing of the common goals also proved to be difficult. However, the problems that turned out to be the most important were a misunderstanding of the idea of clustering and the resulting reluctance to share knowledge, more frequent competition than cooperation, a frowned-upon flow of employees between cluster members, and the resulting lack of trust among cluster participants.

External barriers revealed themselves most often in further periods of a cluster’s functioning. The most important of them was a dependence on external funding. It turned out to be disastrous for some clusters because cluster support activities included in the OP for 2014–20 are scant. As a result, there was a drop in interest in cluster structures. This leads to a very important question posed by this study: Is it not the case that external funds used as part of cluster policy have ‘spoiled’ the idea of clustering in Poland? Perhaps the fact that clusters regarded the acquisition of external financing as their strategic goal was not a good idea? It aroused expectations regarding the inflow of public aid (especially in the case of smaller clusters, which is usually the size of creative clusters), but weakened the care for the ensuring sustainability of relationships and creating the value chain. After all, the clusters that have the best chance to generate added value are those linked by long-term cooperation, numerous projects and by the certainty that they will not cease operation upon the completion of a single project.

The general picture obtained from the study shows that the numerous barriers that were revealed were primarily endogenous in nature (they originated in the cluster itself), especially those appearing in later periods of operation. This contradicts the original research hypothesis. It turns out that cluster participants were aiming more towards the type of relationships typical of ordinary cooperation networks, while still taking advantage of the funding from external funding. The above expectations did not, however, pass the test of time. External projects have ended and the cooperation required for cluster structures to thrive turned out be too demanding. As a result, the current (May 2020) situation is that some of the investigated clusters have suspended their activities, and only a few have managed to become independent of external sources of funding by creating their own mechanisms of functioning. In general, creative activities in Poland proved to be a segment in which clustering is introduced slowly and with numerous obstacles.

The study also found that location and geographical distances, and therefore issues of spatial concentration in general, are not barriers to the development of the analysed clusters. The investigated creative clusters are moving away from the vision of a cluster as a structure determined by spatial concentration and economic specialization. Instead, they are focusing more on the management of cluster organizations.

Moreover, some similarities with the results obtained by other authors studying creative clusters in Central and Eastern Europe were observed. For example, Bontje et al. (Citation2011) and Marková (Citation2014) observed that creative clusters established in this part of Europe are geared towards financial assistance from OP. Jurene and Jureniene (Citation2017) and Kozina and Bole (Citation2018) pointed out that creative clusters are established in the largest urban centres, and Kuleva (Citation2018) noted that creative clusters in Russia are constantly seeking the interest of local authorities. In turn, the review by Bialic-Davendra et al. (Citation2016) confirmed that creative clusters are formed in the region’s largest cities. Attention was also drawn to the lack of mention of clusters in regional development strategies, to the fact that their numbers decrease over time, as well as to their reliance on the financial assistance provided under OP. Most of these observations overlap with the present findings. The difference concerns only one issue: creative clusters in Poland do not tend themselves to be located in the largest cities. Besides, a dependence on external aid, a gradual decrease in the number of cluster structures or a lack of interest on the part of local government are also problems characteristic for Poland. Particularly noteworthy is the lack of utilization of creative clusters in the implementation of regional policy. Creative clusters are interested in taking an active part in the development of their regions to contribute to their economic specialization (cf. Comunian, Citation2017). Meanwhile, it turns out that they cannot count on the cooperation with local government units to build a properly functioning triple helix structure.

The study was conducted among creative clusters, which are characterized by a slightly weaker power and impact. The author is of the opinion that the list of barriers to the development of clusters belonging to KNC may be different (e.g., due to their extensive administration, KNC may experience fewer problems related to organization and management). However, it is the smaller clusters, often less well known, that make up the vast majority of cluster structures in Poland. The study embraced almost all creative clusters in Poland. Only one coordinator decided not to take part in the study. However, this fact could not affect the results obtained. The study is therefore a comprehensive report on the real challenges faced by clusters. Some of them need to be resolved within the structures themselves. However, others result from the conditions in which cluster structures must function in Poland. And here, there is a pressing need for a change in the attitude towards clusters. Otherwise, cluster structures will slowly disappear. This study is therefore intended as food for thought for representatives of local government units who can influence the level of priority assigned to clusters in their regional and local policy and for cluster coordinators/potential coordinators. In future, the author would like to continue research on creative clusters in Poland by, among others, comparing the locations of creative business with the existing creative clusters to identify areas with a potential for clustering (latent clusters).

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The shortage of external linkages of clusters in Poland was described by Abbasiharofteh and Dyba (Citation2018).

2 Darchen (Citation2017) was one author who wrote about a group of entities that finally decided to pursue their common strategic objectives outside the cluster.

REFERENCES

- Abbasiharofteh, M., & Dyba, W. (2018). Structure and significance of knowledge networks in two low-tech clusters in Poland. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1442244

- Banks, M., Lovatt, A., O’Connor, J., & Raffo, C. (2000). Risk and trust in the cultural industries. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 31(4), 453–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-7185(00)00008-7

- Banks, M., & O’Connor, J. (2017). Inside the whale (and how to get out of there): Moving on from two decades of creative industries research. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 637–654. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549417733002

- Bereitschaft, B. (2014). Neighbourhood change among creative–cultural districts in mid-sized US metropolitan areas, 2000–10. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 1(1), 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2014.952770

- Bialic-Davendra, M., Bednár, P., Danko, L., & Matošková, J. (2016). Creative clusters in Visegrad countries: Factors conditioning cluster establishment and development. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 32(32), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1515/bog-2016-0013

- Boix, R., Capone, F., De Propris, L., Lazaretti, L., & Sanchez-Serra, D. (2016). Comparing creative industries in Europe. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(4), 935–940. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414541135

- Boix, R., Hervás-Oliver, J. L., & De Miquel-Molina, B. (2015). Micro-geographies of creative industries clusters in Europe: From hot-spots to assemblages. Papers in Regional Science, 94(4), 753–772. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12094

- Bontje, M., Musterd, S., Kovács, Z., & Murie, A. (2011). Pathways toward European creative-knowledge city-regions. Urban Geography, 32(1), 80–104. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.32.1.80

- Chapain, C., & Comunian, R. (2010). Enabling and inhibiting the creative economy: The role of the local and regional dimensions in England. Regional Studies, 44(6), 717–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903107728

- Child, J., Faulkner, D., & Tallman, S. (2005). Cooperative strategy, managing alliances, networks and joint-ventures. University Press.

- Comunian, R. (2017). Temporary clusters and communities of practice in the creative economy: Festivals as temporary knowledge networks. Space and Culture, 20(3), 329–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331216660318

- Comunian, R., & England, L. (2019). Creative clusters and the evolution of knowledge and skills: From industrial to creative glassmaking. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 99, 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.02.009

- Darchen, S. (2017). Creative clusters? Analysis of the video game industry in Brisbane, Australia (1980s–2014). International Journal of Knowledge-Based Development, 8(2), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKBD.2017.085153

- De Berranger, P., & Meldrum, M. C. R. (2000). The development of intelligent local clusters to increase global competitiveness and local cohesion: The case of small businesses in the creative industries. Urban Studies, 37(10), 1827–1835. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020080441

- Den Hertog, P., & Maltha, S. (1999). The emerging information and communication cluster in the Netherlands. In OECD proceedings. Boosting innovation: The cluster approach (pp. 193–218). OECD.

- Department for Culture, Media and Sport. (2013). Classifying and measuring the creative industries. Retrieved from April 20, 2019, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/203296/Classifying_and_Measuring_the_Creative_Industries_Consultation_Paper_April_2013-final.pdf

- Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class. Basic Books.

- Florida, R., Mellander, C., & Stolarick, K. (2010). Music scenes to music clusters: The economic geography of music in the US, 1970–2000. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(4), 785–804. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4253

- Gibson, C., & Kong, L. (2005). Cultural economy: A critical review. Progress in Human Geography, 29(5), 541–561. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132505ph567oa

- Gong, H., & Xin, H. (2019). Buzz and tranquility, what matters for creativity? A case study of the online games industry in Shanghai. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 106, 105–114. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.002

- Gordon, I. R., & McCann, R. (2000). Industrial clusters: Complexes, agglomeration and/or social networks? Urban Studies, 37(3), 513–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098002096

- Gupta, V., & Subramanian, R. (2008). Seven perspectives on regional clusters and the case of Grand Rapids Office Furniture City. International Business Review, 17(4), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2008.03.001

- Hartley, J., Pottis, J., Cunningham, S., Flew, T., Keane, M., & Banks, J. (2013). Key concepts in creative industries. SAGE Publications.

- Hassink, R. (2005). How to unlock regional economies from path dependency? From learning region to learning cluster. European Planning Studies, 13(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431050010734 doi: 10.1080/09654310500107134

- Heebels, B., & van Aalst, I. (2010). Creative clusters in Berlin: Entrepreneurship and the quality of place in Prenzlauer Berg and Kreuzberg. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 92(4), 347–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0467.2010.00357.x

- Hołub-Iwan, J., & Wielec, Ł. (2014). Opracowanie systemu wyboru Krajowych Klastrów Kluczowych (Development of the selection system of Key National Clusters). PARP.

- Jankowska, B., & Götz, M. (2017). Internationalization intensity of clusters and their impact on firm internationalization: The case of Poland. European Planning Studies, 25(6), 958–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1296111

- Jurene, S., & Jureniene, V. (2017). Creative cities and clusters. Transformations and Business & Economics, 16, 214–234.

- Kowalski, A. M., & Marcinkowski, A. (2014). Clusters versus cluster initiatives, with focus on the ICT sector in Poland. European Planning Studies, 22(1), 20–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.731040

- Kozina, J., & Bole, D. (2018). The impact of territorial policies on the distribution of the creative economy: Tracking spatial patterns of innovation in Slovenia. Hungarian Geographical Bulletin, 67(3), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.15201/hungeobull.67.3.4

- Kuleva, M. (2018). Cultural administrators as creative workers: The case of public and non-governmental cultural institutions in St. Petersburg. Cultural Studies, 32(5), 727–746. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2018.1429005

- Landry, C. (2000). The creative city: A toolkit for urban innovators. Earthscan.

- Mariussen, A. (2001). Millieux and innovation in the northern periphery – A Norwegian/northern European Benchmarking. Nordregio Working Paper.

- Marková, B. (2014). Creative clusters in the Czech Republic – strategy for local development of fashionable concept? Moravian Geographical Reports, 22(1), 44–50. https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2014-0005

- Markusen, A. (1996). Sticky places in slippery space: A typology of industrial districts. Economic Geography, 72, 293–313. doi: 10.2307/144402

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2003). Deconstructing clusters: Chaotic concept or policy panacea? Journal of Economic Geography, 3(1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/3.1.5

- Ministry of Development. (2020). Krajowe Klastry Kluczowe (Key National Clusters). Retrieved from July 19, 2020, from https://www.gov.pl/web/rozwoj/krajowe-klastry-kluczowe

- Mizzau, L., & Montanari, F. (2008). Cultural districts and the challenge of authenticity: The case of Piedmont, Italy. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(5), 651–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbn027

- Morgulis-Yakushev, S., & Sölvell, Ö. (2017). Enhancing dynamism in clusters: A model for evaluating cluster organizations’ bridge-building activities across cluster gaps. Competitiveness Review. An International Business Journal, 27(2), 98–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-02-2016-0015

- O’Connor, J. (2015). Intermediaries and imaginaries in the cultural and creative industries. Regional Studies, 49(3), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748982

- Piore, M. J. (1990). Work, labour and action: Work experience in a system of flexible production. In F. Pyke, G. Becattini, & W. Sengenberger (Eds.), Industrial districts and inter-firm cooperation in Italy (pp. 52–74). International Institute for Labour Studies.

- Podgórska, J. (2016). Charakterystyka klastrów w Polsce – na podstawie analizy PARP (characteristics of Polish clusters – Based on the Polish Agency for Enterprise Development). Ministry of Development.

- Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition. Harvard Business Review, 76, 77–90. Retrieved from September 20, 2019, from https://www.csus.edu/indiv/c/chalmersk/econ251fa12/clustersneweconofcompetition.pdf

- Ratalewska, M. (2016). The development of creative industries in Poland comparison with the European Union. In M. Bilgin & H. Danis (Eds.), Entrepreneurship, business and economics (pp. 57–67). Springer.

- Rosenfeld, S. A. (1997). Bringing business clusters into the mainstream of economic development. European Planning Studies, 5(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319708720381

- Środa-Murawska, S., & Szymańska, D. (2013). The concentration of the creative sector firms as a potential basis for the formation of creative clusters in Poland. Bulletin of Geography. Socio–Economic Series, 20(20), 85–93. https://doi.org/10.2478/bog-2013-0013

- Sternberg, R. (2001). New firms, regional development and the cluster approach – What can technology policies achieve? In J. Bröcker, D. Dohse, & R. Soltwedel (Eds.), Innovation clusters and interregional competition: Advances in spatial science (pp. 341–371). Springer.