ABSTRACT

The public health impacts of climate change, and how they can be addressed through implementable built-environment interventions in non-agricultural-based rural communities, is an understudied area in the academic literature and adaptation planning practice, particularly in the United States. This paper addresses this gap in understanding through a pilot project that developed a climate and health-adaptation plan with Marquette County, a geographically large, coastal, non-agricultural-based, rural community in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. We show how the Deliberation with Analysis model of public participation, supported by visualizations and followed by post-participant surveys to measure its impact on barriers to adaptive capacity, can be used effectively to overcome barriers to adaptive capacity identified in the literature, specifically in understudied non-agricultural-based, rural, coastal communities in the United States. This study contributes to academic debates on adaptation and rurality by displaying the utility of a method that overcomes these key barriers to adaptive capacity noted in past research, specifically a lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

Climate adaptation planning is not a new concept, as hazard-mitigation and adaptation plans have been adopted in communities across the United States (Stults, Citation2017). Widespread hazard-mitigation planning at the local and often urban levels is common, with places such as New York (CDC, Citation2019b) and San Francisco (CDC, Citation2019c) adopting climate and health programmes. However, community planning that accounts for the health impacts of climate change is considerably less common with respect to rural areas in the United States. Even less common is connecting those health impacts directly to proposed built-environment adaptation solutions. With fewer resources spread over broader distances, rural areas face unique challenges regarding climate and health impacts and planning. As stated in the Fourth National Climate Assessment, ‘social science research would improve understanding of the vulnerability of rural communities, strategies to enhance adaptive capacity and resilience, and barriers to adoption of new strategies’ (USGCRP, Citation2018, p. 411). In this writing, adaptive capacity is defined as ‘the ability of a system to prepare for stresses and changes in advance or adjust and respond to the effects caused by the stresses’ (Smit et al., Citation2001, cited in Engle, Citation2011, p. 647).

This project addresses rural climate and health-adaptation planning specifically in the context of non-agricultural-based communities in the United States. Historically, development and land-use policy are a state and local issue in the United States, with regulations varying wildly between states and regions (Pendall et al., Citation2018). In the same manner, climate change adaptation planning has mainly been managed at this state and local level. The Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that, ‘Climate adaptation is context dependent and it is uniquely linked to location, making it predominantly a local government and community level of action’ (Mimura et al., Citation2014, p. 875). With such localized planning, it is important to understand where gaps exist in community planning research. Additionally, barriers preventing adaptation planning and implementation have been noted by Beisbroek et al. (Citation2013) as ‘potentially endless’ (Azhoni et al., Citation2017; Cuevas, Citation2016; Eisenack et al., Citation2014) and highly contextual and interdependent (Eisenack et al., Citation2014). With such localized planning and context-dependent barriers an understanding of climate change adaptation planning in the understudied rural, non-agricultural-based context, is necessary.

As home to 15% of the American population, rural municipalities and institutions often face limited adaptive capacity, adding to their unique concerns and solutions to climate change vulnerability (USGCRP, Citation2018). Facing high rates of vulnerable populations and a relatively long list of disadvantages including physical isolation, high poverty rates and ageing populations, the challenges for rural municipalities and institutions in responding to climate change are different than those of urban areas (Lal et al., Citation2011; USGCRP, Citation2018). Research on climate adaptation in rural areas has predominately focused on developing countries and agricultural communities (e.g., Chaudhury et al., Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2018). While there has been some research internationally on adaptation planning for climate-related health impacts in rural areas, particularly in Australia (Bell, Citation2013; Hanna et al., Citation2011), such research for rural communities remains less common in the United States, especially for areas without an agricultural economic base (USGCRP, Citation2018). While agriculture is obviously significant, non-agricultural-based communities make up over 80% of non-metropolitan counties in the United States (USDA ERS, Citation2015), counties which are of lower density than and are outside of large metropolitan areas (USDA ERS, Citation2013). These places face climate impacts beyond the detriment to farming. Some of these risks include ageing and at-risk communication, transportation, water, and sanitary infrastructure (USGCRP, Citation2018), as well as reduced access, isolation, limited medical facilities and limited emergency services, among other things (Houghton et al., Citation2017). Non-agricultural rural areas face climate impacts such as increased temperatures, flooding, wildfires, drought, wetland loss, heatwaves and extreme events, as well as impacts to economic livelihoods (Angel et al., Citation2018; Gowda et al., Citation2018). Specifically, the Great Lakes coastal areas face increased water temperatures, decreased ice cover, increased storm severity, coastal erosion, flooding, drought and other negative impacts (Angel et al., Citation2018; Fleming et al., Citation2018). All these climate impacts have related health concerns, including increased vector habitats, water contamination, water scarcity, damaged infrastructure, poor air quality days, extended pollen seasons and mental health stressors (Angel et al., Citation2018). Exacerbating these concerns are prevalent and ongoing issues, such as limited code enforcement (Rosser, Citation2006), high poverty rates, economic/social resource dependence, an ageing population, physical isolation, lower income levels, lack of jobs, limited access to the internet, minimum political sway and limited community resources which further limit the capacity to address climate changes (Lal et al., Citation2011; USGCRP, Citation2018). Rural counties have been found to face a ‘climate gap’, defined as ‘the disproportionate and unequal impact the climate crisis has on people of color and the poor’ (Morello-Frosch et al., Citation2009, p. 5). Overall, the interrelated nature of climate change, public health and built-environment solutions in non-agricultural-based rural areas is largely missing from the US adaptation literature.

With funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Climate-Ready States & Cities Initiative (CRSCI), this project addresses that gap by focusing on the interrelated nature of public health, climate change and the built environment in the non-agricultural-based rural, coastal community of Marquette County, Michigan (population 67,145; 1873 square miles of land area) (MSUE & MSU SPDC, Citation2018; US Census Bureau, Citation2019). Specifically, this project aimed to explore how a Deliberation with Analysis planning process supported by visualizations could be used to overcome barriers to adaptive capacity in the community using follow-up surveys to measure impact.

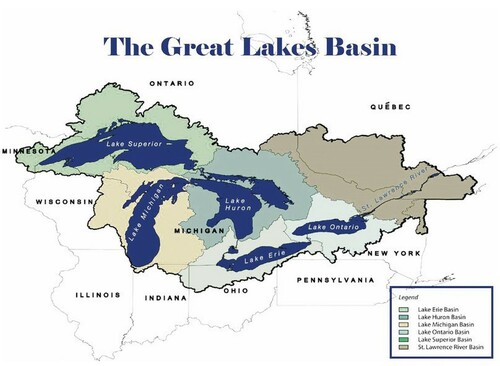

displays the larger Great Lakes Basin that Marquette County sits in within North America. The county is located on the southern shore of Lake Superior in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

Figure 1. The Great Lakes Region of North America.

Source: Ohio Department of Natural Resources (Citationn.d.).

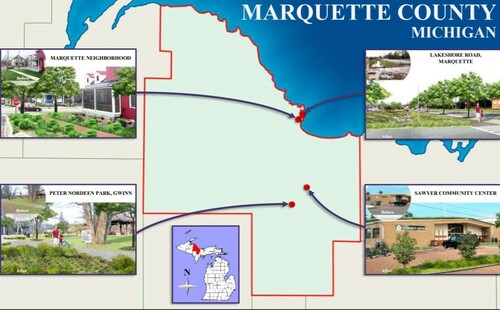

displays where Marquette County is located within Michigan. Within this county, shows several key locations being impacted by climate and health challenges and displays some before and after imaging produced from this process that displayed proposed interventions.

Figure 2. Location of Marquette County, Michigan.

Source: Marquette County Resource Management/Development Department (Citation2007).

Figure 3. Locations of key climate concerns in Marquette County.

Source: Original work of Michigan State University.

Through a partnership between the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS), the Michigan Climate and Health Adaptation Program (MICHAP), Michigan State University Extension (MSUE), the Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction (MSU SPDC), the Marquette County Health Department (MCHD) and other local leaders including the Marquette Climate Adaptation Task Force (CATF), this Deliberation with Analysis and visualizations planning process resulted in the first two volumes of the Marquette Area Climate and Health Adaptation Guidebook MSUE and MSU SPDC (Citation2018). Post-process participant surveys were used to assess how the process changed participants’ understanding of adaptation for Marquette County as well as the community’s overall adaptive capacity.

This paper seeks to fill gaps in the academic understanding around climate and health-adaptation planning in non-agricultural-based rural, coastal communities, specifically focusing on barriers to adaptive capacity such as a lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016). The planning process used attempts to overcome commonly cited barriers to adaptation planning, and the post-process participant surveying sought to quantify that impact. Specifically, the research attempts to address the following question: Does the Deliberation with Analysis framework with the use of visualizations for climate and health-adaptation planning help overcome commonly cited barriers to climate adaptation and increase countywide adaptive capacity in a non-agriculturally based rural, coastal setting in the United States?

PAST ACADEMIC AND POLICY WORK ON RURAL CLIMATE AND HEALTH ADAPTATION

Academic work

Studies of the impact of climate change on larger urban coastal areas (Owrangi et al., Citation2017) or even on mid-sized metropolitan regions (Runkle et al., Citation2018) are common. These studies provide methods for planning in the context of waterfront communities but provide little for low-density rural settings with higher geographical diversity. Studies focused on public engagement on topics of climate change, public health and the built environment have only addressed two of these three themes at once (Bajayo, Citation2012; Botchwey et al., Citation2014). Without past research able to show the impact of simultaneously bringing together the three themes of climate change, public health and the built environment and surveying participants, it is hard to know whether these past efforts have had intended impacts of growing adaptive capacity among local community organizations.

Globally, numerous barriers to climate adaptation have been identified. These largely relate to a lack of resources (including funding and capacity), lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016). Although this process could not solve funding shortages, it sought to clearly respond to the other four barriers mentioned above.

While some nationally or globally comprehensive studies on barriers exist (Bierbaum et al., Citation2013; Biesbroek et al., Citation2013) most research has been context specific (e.g., Azhoni et al., Citation2017; Carmin et al., Citation2012; Measham et al., Citation2011; Raymond & Robinson, Citation2013). This study sought to follow this trend of location-specific studies while filling a gap focusing on a unresearched geography. Of the contexts studied, most of the research on barriers has been conducted in developing countries. Of North American research on barriers and enablers, New England (Hamin et al., Citation2014; Lonsdale et al., Citation2017), the Rocky Mountains (Lonsdale et al., Citation2017), the Intermountain West (Dilling et al., Citation2017), the Great Plains (Wood et al., Citation2014), the ocean coast (Casey & Becker, Citation2019), and urban areas of Michigan (Nordgren et al., Citation2016) have all been studied, yet no research looks specifically at the unique location of the rural, coastal communities in the Great Lakes Region. This lack of focus on rural, coastal communities in the Great Lakes in the manner approached here is also present in other CRSCI-funded programmes.

Policy work

Major global public health agencies have identified climate change as one of the greatest threats facing human health (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2018). Around the world countries are working to adapt to existing changes and mitigate future changes. In the United States, the CDC has recognized nationally the impact that climate change will have on public health, and has proactively established the CRSCI (CDC, Citation2017, Citation2019d). Despite global and national attention, clear gaps in understanding rural community responses to the public health impact remain, particularly in the United States.

In reviewing CRSCI programmes around the nation, most climate and health planning is approached as guidance to local health departments for provisioning public services (CDC, Citation2017) rather than a collaborative engagement effort to overcome barriers to adaptive capacity and identify built-environment adaptations, although some communities have used the latter approach. For example, Wisconsin’s detailed community engagement toolkit (Wisconsin Climate and Health Program, Citation2016) provides state-wide guidance on topics such as stakeholder engagement, impact prioritization and action planning. Missing is detailed planning and landscape recommendations to mitigate the impact of climate change on public health, and a local-level, context-specific focus.

New York State, another CRSCI grantee, has also developed a method to engage local communities in climate planning. Since 2018, their Climate Smart Communities (CSC) programme has established a process for communities to become certified in adaptation and mitigation action (New York State, Citation2019). This programme is available to large and small communities and has been undertaken by dozens of small upstate communities. However, despite its applicability to climate adaptation planning, it lacks the clear public health approach called for in CDC funding.

Looking specifically at the state of adaptation planning in Michigan, only 14 Michigan cities have a plan or goal in place to tackle climate change (Winowiecki & Williams, Citation2019). These vary from emissions reductions goals to comprehensive plans. Larger or more urban communities in the lower peninsula have focused in some fashion on sustainability such as Flint’s (population 97,810) and Bay City’s (population 33,736) master plans (City of Bay City, Citation2017; City of Flint, Citation2013; US Census Bureau, Citation2019) and Detroit’s (population 679,865) specific Climate Action Plan (Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice, Citation2017), which has been incorporated into the city’s Sustainability Plan (City of Detroit, Citation2019). These plans seek to address climate change in a local context through adaptation and sustainability measures. Additionally, some Upper Peninsula communities near Marquette County are deeply engaged in climate adaptation planning processes. Examples include progressive plans from the nearby City of Hancock (population 4574) (City of Hancock, Citation2017; US Census Bureau, Citation2019) attuned to the challenges climate change brings to rural regions and a region-wide comprehensive review of all local sustainability plans (Central Upper Peninsula Planning and Development, Citationn.d.). None of the Michigan plans reviewed specifically took the approach of addressing the interrelated nature of climate change, the built environment and public health.

These examples show the irregularity of finding climate change, public health and the built environment considered simultaneously. This integrated approach used in a rural, coastal community coupled with visualizations as a part of engagement and follow-up surveys to quantify the growth in local adaptive capacity has made this project unique amongst the CRSCI grantees and within the state of Michigan.

RESEARCH METHODS

Planning engagement method: deliberation with analysis

The project used a modified Deliberation with Analysis methodology of participatory planning for building community support and consensus and overcoming commonly cited barriers to adaptation planning and implementation. The Deliberation with Analysis method was selected based on previous adaptation planning efforts in Michigan on which members of the project team were included (Crawford et al., Citation2018). In these previous research efforts, Crawford et al. (Citation2018, p. 287) justified this methodology as follows:

Schreck and Vedlitz’s (Citation2016) review of public opinion and participation in public forums on global warming found a strong association between strength of opinion and participation in public dialogue. The association suggests a polarised situation as the starting point for public deliberations and policy discussions. US citizens are also considered more polarised on climate change than any other wealthy country (Kennedy, Citation2015). Related research from cognitive psychology reveals that people are influenced by group values and will lean their positions towards ones that reinforce their connections with others in social groups (Kahan, Citation2010). For this reason, and others, a solid body of literature recommends using a process called ‘Deliberation with Analysis’ when communities are collectively addressing complex, value-laden issues such as climate change (National Research Council, Citation2008, Citation2010).

Selection criteria

The initial engagement process began with the identification of a community willing and able to take on a major, multi-year climate and health-adaptation project. Based on several criteria, Marquette County was approached to participate. These criteria were: (1) a rural county; (2) a relatively advanced level of climate adaptation readiness and planning; and (3) agencies supportive of the project. The first criterion addressed the gap in research and the second and third criteria were required to ensure project success. The county also filled a gap in climate adaptation planning understanding as a rural, coastal, non-agriculturally based community. In tandem with the Deliberation with Analysis methodology, this process was informed by the CDC’s Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) framework. As is noted by the CDC, ‘BRACE is a five-step process that allows health officials to develop strategies and programmes to help communities prepare for the health effects of climate change’ (CDC, Citation2019a). Much like the analysis function in Deliberation with Analysis, BRACE incorporates local-specific data into planning to develop a Climate and Health Adaptation Plan and long-term evaluation of the plan’s recommendations (CDC, Citation2019a; Marinucci et al., Citation2014).

Survey method

To measure impact and understand how the process addressed commonly cited adaptation barriers, post-process participant surveys were used. This method was informed by similar research by others which largely used surveys to identify barriers and enablers of adaptation planning (e.g., Azhoni et al., Citation2017; Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Carmin et al., Citation2012; Measham et al., Citation2011; Nordgren et al., Citation2016). Following this model, participants involved were surveyed to assess changes in adaptive capacity. Before and after questions using a seven-point Likert scale measured changes for participants pre- and post-meeting. These questions sought to specifically enquire about barriers to adaptation noted in the previous literature such as a lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016).

This data collection consisted of a survey distributed at the January 2019 Climate and Health Adaptation Implementation Prioritization Workshop. This workshop involved 50 public officials from around Marquette County, representing local units of government, the county and the region, and at least 28 organizations. The attendees were invited based on their previous participation in the project since 2017 as well as their role related to climate and health policy implementation in the county. The original invite for the workshop went to 80 plus participants through email, and participants were then called to encourage they attend. CATF, consisting of members known throughout the community, sent the invitations and made the follow-up calls. Of those attending the meeting, 31 participants completed the survey. The complete survey consisted of 21 questions mostly evaluating the overall project effectiveness and suggested improvements, with the Likert-scale portion of answers noting how participants felt this process changed local adaptive capacity. The results reported here report on those questions that specifically addressed adaptive capacity barriers.

Process

This project developed over two years and three phases. The first phase consisted of stakeholder engagement, issue identification and best practices research. The second phase included design and policy development with impact measurements. shows the timeline of the first two phases of engagement, while explains the detailed components of each step of the process. The results and discussion closely follow the process explained in .

Figure 4. Phases 1 and 2 planning process (pre-survey).

Source: MSUE and MSU SPDC (Citation2019).

Table 1. Phases of the deliberation with the analysis process used in Marquette, with subprocesses and their related data-collection steps.

Methodological limitations

The methodology used here was limited by the fact that this genuine community engagement process could not ensure the same participants equally participated at each step of the engagement process. As a result, the survey results show the responses of those who attended the third phase of the process at which point surveys were distributed. In addition, while this process did show beneficial outcomes in Marquette County, its function as an example of successful processes is most applicable on rural, coastal communities in the Great Lakes Region, especially those who begin the planning process already concerned about the impacts of climate change. Appreciating a community’s pre-existing understanding of climate issues is essential, and this process engaged a community already at the ‘alarmed’ stage of Yale University’s climate change spectrum (Yale Program on Climate Change Communications, Citation2016). This may not be the case in all rural, coastal communities in the United States and beginning here was critical for wider engagement. Survey data were also representative of those who were surveyed and chose to participate in this planning process and may not be necessarily reflective of all such participants in all communities.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

First, we share what engaging in the planning process described in the methodology resulted in at each step. We then discuss the survey results and focus closely on these tangible metrics for further discussion.

Results from the planning engagement process

Phase 1: Initial engagement

After selection of Marquette County based on the criteria identified in the research methods, we began work on the planning process closely partnering with local agencies. With a well-established adaptation community, buy-in from certain key players was essential. The CATF was a local entity collaboratively advancing adaptation action in the county. This committee met on several occasions with the project team in phase 1 and a further five times during phase 2. CATF’s overarching role was to act as a local champion and expert in advancing climate adaptation for the region. During this plan it functioned as the plan steering committee, guiding how plan development progressed. The Superior Watershed Partnership (SWP), a regional body supporting efforts to protect the greater Lake Superior watershed, and the MCHD were also important partner organizations. The MCHD health officer especially acted as a trusted public health leader and connection to other local health care actors and agencies servicing vulnerable populations. A well-established MSUE educator in the community connected and communicated between the project team and the community partners. All these organizations were involved in past efforts to address concerns related to climate change and the position of Marquette County on the south shore of the largest Great Lake and its perceived vulnerability.

Next, the community partners assisted the project team in identifying key community stakeholders representing vulnerable populations within the county. Vulnerable populations included those most susceptible to the negative health consequences of climate change, such as veterans, homeless residents and senior citizens. Stakeholders related to local government, climate change research and planning, academia, economic development, and health also participated from the outset.

After this, the groups engaged in a series of facilitated discussions and key informant interviews with the project team, with just over 100 participants from 23 stakeholder groups participating. The initial discussions involved a dialogue that informed stakeholders about the climate/health connection and asked them to reflect on the conditions they observed in the community. The discussions elicited a list of priority concerns that formed the heart of later work in plan development. shows the priority concerns approved by the plan steering committee (CATF) as the focus areas to address in the community engagement process and recommendations. Secondary priorities were also included as focus areas to move forward with. The feedback of this phase was summarized in a formal report.

Table 2. Focus areas following the phase 1 input process.

Phase 2: Public engagement and plan development

With the climate and health priorities established through phase 1 of the project, and CATF and MCHD support established, the second phase sought broader resident input through Deliberation with Analysis. In November 2017, the project team held a kick-off community visioning meeting. At the meeting background and context on the connection between climate and health, illustrated using the ‘Pathways’ concept (Schramm et al., Citationn.d.), was presented. After the educational overview, the team asked the community the following questions (MSUE & MSU SPDC, Citation2018):

Individually, ‘What do you think are the biggest climate and health threats facing Marquette County? Think in terms of priority threats previously identified such as water quality, flooding, water shortage, and wildfires. You may identify other relevant threats as well.’

In groups: ‘Imagine that you have been away for 20 years and you just came back. With the best hope for your community, how has it changed? What does this area look like in 20 years after the climate and health impacts have been fully addressed? Who lives there? What are they doing? What is housing like? How are people getting around? What amenities and infrastructure are there?’

In groups, rank the major climate change and health priorities of Marquette County.

Participants worked individually and in small groups to express concerns and develop a vision of a climate and health adapted future for the county. Sticky notes, poster boards, maps, coloured dots and feedback sheets were all used to record input. Participants used maps of the project area to identify specific locations of climate and health concern. Visuals developed by the project team showed the community examples of potential adaptation interventions.

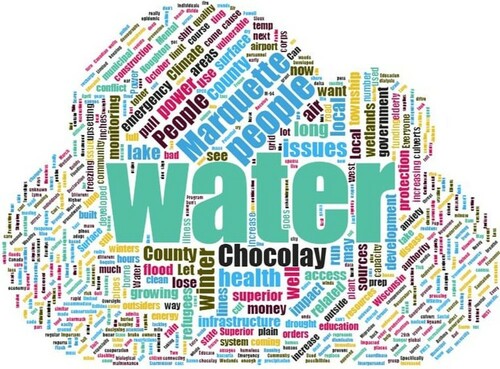

Community concerns raised in these sessions focused on the state of mass transportation and evacuation systems, inadequate energy systems, a lack of affordable housing, the growth of vector-borne diseases, extreme rain events and flooding, and inadequate infrastructure, especially with respect to regional stormwater systems and walkability. Numerous ideas for the future of the community were expressed. The ranking of climate and health concerns for the community is captured in the word cloud shown in , clearly identifying water-related concerns as a main priority for the community. Word clouds expressed the frequency in which words are used through the size of the word displayed.

Figure 5. Community concerns represented in a word cloud.

Source: MSUE and MSU SPDC (Citation2018).

The priority concerns of the community input fell into four key areas of climate-related health concerns: vector awareness, air quality, emergency response/extreme events and water-related issues.

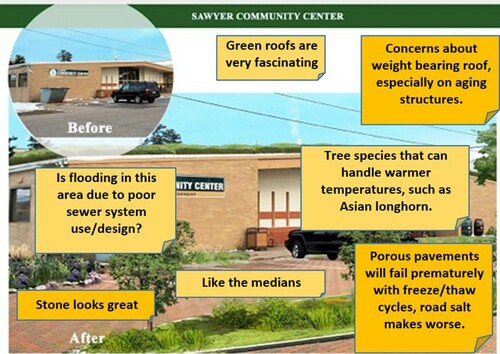

In response to the feedback, design interventions and policy recommendations were developed concurrently by the project team to reflect the community’s hopes and concerns. Visualizations were used to gather meaningful input, as past research has shown they can be an effective tool in climate change-related community planning (O’Neill et al., Citation2009, Citation2013, Hart & Feldman, Citation2016). The visual designs were intended to educate the public on adaptation measures and foster discussion and deliberation. Visuals make the abstract discussion of climate change more tangible by envisioning a localized climate-adapted future community and expressing the health and place-making benefits of adaptation. displays what some of these visualized interventions looked like when mapped on to actual locations within Marquette County.

Policy recommendations accompanying visuals were developed through an extensive review of current practices in climate adaptation planning. Best practices to address the concerns were sought from the current published literature through a comprehensive literature review, with attention paid to strategies applicable to rural communities that met the health-related goals of the project. Simultaneously, Marquette County plans and initiatives were reviewed to identify where these best practices could be implemented.

During this phase, a set of locally relevant health-related metrics was also identified in order to allow leaders to track progress. Presented as ‘sample health measures’ these metrics were diverse and inclusive such as gallons of runoff diverted by low-impact development to measure impacts of water quality and flooding adaptations; number of low pollen-producing plant and tree species planted to reduce the impact of allergens; and tick-specific educational signs in public places to measure the impacts of vector-borne disease adaptations.

The suite of design interventions, policy recommendations and health metrics proposals were presented to the community at a public meeting in March 2018.

At the second community meeting, before and after design images and sample policy recommendations were on display. Participants used sticky notes to comment directly on the images and feedback sheets were used to gather detailed input. displays the results of this input session from the community. shows what feedback received looked like when placed on visualizations of climate-adapted county locations.

Figure 6. Design feedback image example.

Source: MSUE and MSU SPDC (Citation2018).

Table 3. Design input summary from the public meeting held in March 2018.

The comments at the meeting were used to refine the design and policy recommendations to address the community’s concerns. The CATF steering committee provided input on the final policy recommendations through a technical review subcommittee. The technical review committee was made up of several CATF and MCHD members with expertise and positions of authority in local public health, planning and community development, and environmental advocacy. As mentioned above, this committee met on several occasions with the project team in phase 1 and a further five times during phase 2, fulfilling their key role to function as local experts in advancing climate adaptation for the region and working as a plan steering committee. This last review ensured the recommendations were locally relevant and feasible, and that they related well to local initiatives.

The process resulted in the Marquette Area Climate and Health Adaptation Guidebook, published in two volumes. Volume I: Stakeholder Engagement and Visual Design Imaging was intended to educate the public as a document easily understandable by a broad audience. It included visual before and after imaging of Marquette County locations and explained how built-environment interventions could interrupt the climate health-impact pathway. It documented the iterative engagement process to ensure plan transparency, critical for gaining legitimacy (Weston & Weston, Citation2013). Volume II: Policy and Metric Recommendations was developed for a technical and policy-oriented audience including the community’s public officials and decision-makers. It included an extensive list of over 50 goals and 140 strategies categorized by focus issue.

Public agency support for volumes I and II

Following the iterative process and the publication of the Marquette Area Climate and Health Adaptation Guidebook, it was critical that the volumes presented be embraced by the local community. As a critical step revealing the effectiveness of the engagement process executed, CATF endorsed the final product. The final report was subsequently presented to the Marquette County Commission and the County Health Department and then distributed to the organizations and jurisdictions of the county. Due to the multijurisdictional nature of the project and cross-boundary recommendations of the guidebooks, organizations with a broad range were needed to take formal ownership of the report to ensure their credibility and implementation. Through various means, county organizations used the report to enhance their own message, endorse the plan and take ownership.

Results from the surveys

After the above process was completed in late 2018, members of the planning team at Michigan State University surveyed attendees of the January 2019 Climate and Health Adaptation Implementation Prioritization Workshop regarding whether they felt that this process had had a sizeable impact on their understanding of this issue and particularly their ability to overcome barriers to adaptation noted in past research of this issue. A key part of this process was to grow adaptive capacity of the local community, and these surveys sought to better quantify any change in this adaptive capacity that came about through this process. As noted above, this phase was informed by previous surveying efforts done to assess climate change planning(Azhoni et al., Citation2017; Carmin et al., Citation2012; Measham et al., Citation2011).

Following the presentation and adoption of the two-volume report, staff completed surveys with community participants to assess whether participants agreed on an increase in adaptive capacity. To assess the impact of these efforts, the geographical diversity of survey participants was critical. Of the 22 local units of government in Marquette County, at least 10 had representative residents participate in this survey. displays this geographical diversity.

Table 4. Community of residence of survey participants.

A noteworthy limitation of this survey, however, was that not all participants attended an equal number of sessions, with half attending their first climate planning meeting that used this method in that January 2019 gathering. displays the breakdown of this attendance. However, at all meetings organized by the project teams, the deliberation with the analysis method was used, exposing all participants to this iterative method of growing in understanding about climate change and health adaptation.

Table 5. Meetings attended by survey participants.

The full results of the survey are displayed in . As is noted in the methodology, these questions sought to specifically enquire about barriers to adaptation noted in previous literature such as a lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016).

Table 6. Results of the post-participant survey of Deliberation with Analysis participants.

Survey results showed improvements in all categories, including issues around knowledge about climate change and local efforts, confidence in actively collaborating across municipal boundaries, and confidence in the capacity to plan and implement changes in the future around climate and health adaptation.

Discussion of the survey results

Observations that arose from survey results centred around clearly known barriers to adaptive capacity. Specifically, questions shed a light on issues around: (1) a lack of public awareness; (2) a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information; (3) a lack of leadership; and (4) limited coordination and competing priorities, all barriers to adaptive capacity noted by past research (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016). However, before assessing the responses to these questions, it is critical to understand where the Marquette County community started this process.

Understanding a community’s adaptation starting place aligns with the experience of previous research noting the importance of understanding community identity and potential resistance to climate planning (Crawford et al., Citation2018). Crawford et al. (Citation2018) noted how Deliberation with Analysis is an effective tool at addressing issues, such as climate change, where ‘people are influenced by group values and will lean their positions towards ones that reinforce their connections with others in social groups’ (Kahan, Citation2010, as cited in Crawford et al., Citation2018, p. 287). Yale University described individuals and communities as existing on a spectrum from ‘alarmed’ about climate change to ‘dismissive’ (Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, Citation2016). Previous research identified Marquette County as in or near the ‘alarmed’ category, making it easier to focus on adaptation (Crawford et al., Citation2018). The starting values of this survey results reaffirmed this assumption from the beginning of the planning process.

As observed in , across all questions regarding how well people were prepared before participation on a series of adaptive capacity questions, all answers neared or surpassed 4 out of 7, displaying that past climate planning efforts in the region had brought a group of participants to the table who were somewhat familiar with climate adaptation. The role of local trusted leaders, including the MCHD and the local MSU extension educator proved crucial to engaging with the community. By beginning this process in a local community that had a network of grassroots stakeholders connected to the project team through the local health department and extension office the process could more easily engage a representative group aware of climate adaptation planning efforts.

Addressing public awareness and understanding climate change information: questions 1–5

In understanding this adaptive capacity, the first five questions addressed adaptive capacity barriers around public awareness and understanding climate change information. Deliberation with Analysis specifically seeks to expand knowledge of a topic by engaging the local community in iterative feedback loops centred on building the adaptive capacity of the community. The most noteworthy gain for participants in knowledge was on question 4, the issue of locally relevant climate adaptations, with average scaled scores of knowledge growing during the process from 4.16 out of 7 to 5.17 (). This growth was particularly beneficial for this study given that climate adaptations in rural, coastal, non-agricultural settings have not been extensively studied previously in an American context.

Beyond this growth in understanding locally relevant climate adaptations, there was also clear growth in project participants’ understanding of climate change as a larger issue, with knowledge growing in question 1 by 0.81/7 points on average, and an understanding of the impact of climate change on Marquette County specifically in question 2 by 0.84/7 points. These gains, while modest, showed the benefit of engaging in a deliberative process of information-sharing and research to better understand the unique local needs of Marquette County.

Through funding from the CDC and co-led by the MDHHS, one project goal was to expand understanding of the connection between climate change and public health. It was then encouraging to see that after following this process, local understanding about the health impacts of climate change in question 3 grew by 0.71 points on average. With a baseline understanding of climate’s impacts and its connections to health as a focal point, this project was clearly successful in expanding local knowledge about climate change efforts.

Question 5 focused on where these participants could locate locally relevant, quality information on climate adaptations. Here there was an average gain in understanding of 1.09 points. This showed that local decision-makers better understood where to obtain the information needed to make decisions in their communities to implement locally specific changes. Having knowledge to do this is a key part of adaptive capacity and it showed that through this planning process participants not only had a plan they could use to guide future decision-making but also they knew where to obtain information to address issues that may not have been covered in the planning process.

Growth in a belief in the local capacity to act: addressing leadership and coordination (questions 6–10)

Responding to noted adaptive capacity barriers around a lack of leadership and limited coordination and competing priorities, questions 6–10 shed a light on these barriers. On the question of being aware of adaptive actions being taken throughout Marquette County in question 6, there was the largest increase in knowledge of any question asked with an average gain of 1.10 points. Adaptive capacity specifically seeks to improve understanding in order to address an issue (Smit et al., Citation2001). This project sought to better coordinate efforts across Marquette County leadership and the varying communities that made up this process, as limited coordination between levels of government was noted by Biesbroek et al. (Citation2013) as a repeatedly identified issue preventing climate adaptation. With residents of 10 separate communities participating in this survey process, coordination across those communities in the county would be essential. This project’s ability to grow participants’ understanding across the county of existing efforts is key to preventing duplication and to ensure that any efforts undertaken would be efficient and effective. The growth in this cross-community awareness expressed in this survey shows the true impact of deliberative engagement and overcomes key previously identified barriers to adaptive capacity centred on limited coordination.

The questions presented addressed how well prepared local officials felt the community was to address these challenges. The two questions asked in this category specifically sought to determine whether the individual communities in Marquette County felt prepared to engage in the adaptive behaviours spelled out in the plan produced and displayed in volumes I and II. With respect to individual communities in question 7, respondents averaged an increase of 0.96 points in confidence that their organization was capable of planning for and addressing climate change. Using the definition of adaptive capacity as identified by Smit et al. (Citation2001), which focuses on the ability of systems to prepare for the changes climate change will bring, this growth in confidence of local capability was a crucial outcome of this process.

However, beyond the kind of confidence needed for a community to believe that it could plan for the impacts of climate change on public health through built-environment interventions, the process set out to encourage communities to actually engage in a community planning processes. As noted in question 8, participants’ growth of 0.95 points on average of the confidence their organizations would engage in climate adaptation showed that this process, if subtly, did increase the likelihood that local organizations would use the recommendations made to improve their community’s readiness for the inevitable impacts of climate change. One of the goals of this process was to engage in a planning effort that would lead to implementable change. The measured growth in confidence of local officials that their organizations not only could implement recommendations, but that they would, was a meaningful outcome that validated the efforts of this process.

Questions 9 and 10 sought to understand how this process changed perceptions across municipal boundaries. Since Marquette County is home to 22 different municipalities all operating within America’s highly localized system of land-use policy implementation, this kind of cross-boundary participation was critical to ensuring that the kinds of policies advocated for in the final plan were adopted. These last two questions showed consistent gains in line with the scale of gains measured in the other series of questions. Regarding how actively connected organizations felt to other organizations in the county (question 9), an average gain of 1.07 points was measured. Throughout the project this planning process sought to explicitly remove barriers between municipalities and better engage local officials. This gain demonstrates that, while not dramatic in its change, greater confidence was achieved in terms of cross-municipal collaboration.

Finally, ensuring that local entities felt included in this process was important to overcome the barriers of limited coordination. Question 10 clearly showed a gain in local participants’ feeling that the organizations that they represented were included in the process around climate and health adaptation. An average increase of 1 point was noted here and displays real, measurable gains that could lead to better cross municipal border collaboration as noted in the previous question.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

The CRSCI programme affords communities with the opportunity to implement localized solutions to reduce the negative public health impacts of climate change. While communities have approached this opportunity in a variety of ways, this project presents a unique process of connecting climate change, public health and the built environment in a rural, coastal, non-agriculturally based region. By using an informed and modified Deliberation with Analysis method combined with the CDC’s BRACE framework and including follow-up participant surveying, this project provides a useful model that can be applied to other communities considering a similar climate and health planning effort.

While this planning process was unable to address the issue of a lack of funding to implement planning efforts, it sought to clearly respond to the adaptive capacity barriers noted in previous research. These issues of a lack of public awareness, a lack of or difficulty understanding climate information, a lack of leadership, and limited coordination and competing priorities were then the focus of follow-up surveying of process participants. On all surveyed questions that asked about these adaptive capacity barriers, improvement among progress participants was clearly observed. Further research is needed in using this methodology in other rural, coastal, non-agriculturally based communities outside of the Great Lakes Region and in other similar non-agriculturally based rural communities globally. While this process was able to begin in a community already at an advanced stage of climate change planning, it would be beneficial for future work to assess the impact of using Deliberation with Analysis in communities less deeply engaged in previous climate adaptation planning processes to see if such a detailed engagement process could produce results with such community support.

The results of this study can be referenced by similar rural, non-agricultural coastal communities, and the planning process modified and improved to suit other communities depending on the starting point they are at in the Yale climate change spectrum (Yale Program on Climate Change Communications, Citation2016). Specifically for those communities already considered to be ‘alarmed’ or ‘concerned’ about the impacts of climate change in the Yale climate change spectrum, Deliberation with Analysis provides a template for how non-agricultural rural communities can overcome the key barriers to adaptive capacity noted in this piece and identified by past researchers (Biesbroek et al., Citation2013; Measham et al., Citation2011; Oulahen et al., Citation2018; Uittenbroek, Citation2016). This process is specifically useful in international contexts where climate adaptation planning is conducted at a local level small enough to engage directly with decision-makers in a meaningful way, and therefore the governance level at which climate adaptation planning is undertaken is critical when determining applicability. These results particularly speak to this methodology’s applicability in overcoming these barriers to adaptive capacity in rural, coastal, non-agricultural communities rather than larger, denser places.

In using Deliberation with Analysis and producing locally relevant visualizations to engage participants, local communities can engage in a meaningful process that develops implementable community plans and produces measurable changes in communities’ adaptive capacity to address the public health impacts of climate change through interventions in the built environment.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Lorraine Cameron MPH, PhD, and Aaron Ferguson MPA of the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS). Michigan State University student Jason Derry also assisted in the production of mapping images.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Angel, J., Swanston, C., Boustead, B. M., Conlon, K. C., Hall, K. R., Jorns, J. L., & Todey, D. (2018). Midwest: Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States. In D. R. Reidmiller, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, K. L. M. Lewis, T. K. Maycock, & B. C. Stewart (Eds.), Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II (pp. 863–931). US Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH21

- Azhoni, A., Holman, I., & Jude, S. (2017). Contextual and interdependent causes of climate change adaptation barriers: Insights from water management institutions in Himachal Pradesh, India. Science of the Total Environment, 576, 817–828. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.151

- Bajayo, R. (2012). Building community resilience to climate change through public health planning. Health Promotion Journal of Australia: Official Journal of Australian Association of Health Promotion Professionals, 23(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1071/HE12030

- Bell, E. J. (2013). Climate change and health research: Has it served rural communities? Rural and Remote Health, 13(1), 1–16.

- Bierbaum, R., Smith, J. B., Lee, A., Blair, M., Carter, L., Chapin, F. S., & Verduzco, L. (2013). A comprehensive review of climate adaptation in the United States: More than before, but less than needed. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 18(3), 361–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9423-1

- Biesbroek, G. R., Klostermann, J. E. M., Termeer, C. J. A. M., & Kabat, P. (2013). On the nature of barriers to climate change adaptation. Regional Environmental Change, 13(5), 1119–1129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-013-0421-y

- Botchwey, N. D., Trowbridge, M., & Fisher, T. (2014). Green health: Urban planning and the development of healthy and sustainable neighborhoods and schools. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 34(2), 113–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X14531830

- Brown, I., Martin-Ortega, J., Waylen, K., & Blackstock, K. (2016). Participatory scenario planning for developing innovation in community adaptation responses: Three contrasting examples from Latin America. Regional Environmental Change, 16(6), 1685–1700. https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-015-0898-7

- Carmin, J., Nadkarni, N., & Rhie, C. (2012). Progress and challenges in urban climate adaptation planning: Results of a global survey. (null, Ed.) (Vol. null).

- Casey, A., & Becker, A. (2019). Institutional and conceptual barriers to climate change adaptation for coastal cultural heritage. Coastal Management, 47(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08920753.2019.1564952

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CD). (2019d). Climate effects on health. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Climate ready states & cities initiative grantees. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/crsci_grantees.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019a). BRACE framework. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/BRACE.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019b). New York City climate and health program. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/state-programs/nyc.htm

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2019c). San Francisco climate and health program. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/state-programs/sf.htm

- Central Upper Peninsula Planning and Development. (n.d.). Priorities in climate adaptation plans 2011–2016. http://www.centralupdashboard.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ClimateAdaptationCentralUP.pdf

- Chaudhury, A. S., Thornton, T. F., Helfgott, A., Ventresca, M. J., & Sova, C. (2017). Ties that bind: Local networks, communities and adaptive capacity in rural Ghana. Journal of Rural Studies, 53, 214–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2017.05.010

- City of Bay City. (2017). City of Bay City, Michigan Master Plan 2017. https://www.baycitymi.org/DocumentCenter/View/1639/Bay-City-Master-Plan

- City of Detroit. (2019). Detroit Sustainability Action Agenda. https://detroitmi.gov/sites/detroitmi.localhost/files/2019-06/Detroit-Sustainability-Action-Agenda-Web.pdf

- City of Flint. (2013). Imagine flint: Master plan for a sustainable flint. http://imagineflint.com/Documents.aspx

- City of Hancock. (2017). Hancock Master Plan. http://www.cityofhancock.com/docs/City_of_Hancock_Master_Plan.pdf

- Crawford, P., Beyea, W., Bode, C., Doll, C., & Menon, R. (2018). Creating climate change adaptation plans for rural coastal communities using deliberation with analysis as public participation for social learning. Town Planning Review, 89(3), 283–304. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2018.17.

- Cuevas, S. C. (2016). The interconnected nature of the challenges in mainstreaming climate change adaptation: Evidence from local land use planning. Climatic Change, 136(3), 661–676. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-016-1625-1

- Detroiters Working for Environmental Justice. (2017). Detroit climate action plan. https://detroitenvironmentaljustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CAP_WEB.pdf

- Dilling, L., Pizzi, E., Berggren, J., Ravikumar, A., & Andersson, K. (2017). Drivers of adaptation: Responses to weather- and climate-related hazards in 60 local governments in the Intermountain Western U.S. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(11), 2628–2648. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16688686

- Eisenack, K., Moser, S. C., Hoffmann, E., Klein, R. J. T., Oberlack, C., Pechan, A., Rotter, M., & Termeer, C. J. A. M. (2014). Explaining and overcoming barriers to climate change adaptation. Nature Climate Change, 4(10), 867–872. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2350

- Engle, N. L. (2011). Adaptive capacity and its assessment. Global Environmental Change, 21(2), 647–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.019

- Fleming, E., Payne, J., Sweet, W., Craghan, M., Haines, J., Hart, J. F., Stiller, H., & Sutton-Grier, A. (2018). Coastal effects. In D. R. Reidmiller, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, K. L. M. Lewis, T. K. Maycock, & B. C. Stewart (Eds.), Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume II (pp. 322–352). US Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH8

- Gowda, P. H., Steiner, J., Olson, C., Boggess, M., Farrigan, T., & Grusak, M. A. (2018). Agriculture and rural communities. Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: The Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume II (ch. 10). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018.CH10

- Gray, S., Jordan, R., Crall, A., Newman, G., Hmelo-Silver, C., Huang, J., Novak, W., Mellor, D., Frensley, T., Prysby, M., & Singer, A. (2017). Combining participatory modelling and citizen science to support volunteer conservation action. Biological Conservation, 208, 76–86. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2016.07.037

- Hamin, E. M., Gurran, N., & Emlinger, A. M. (2014). Barriers to municipal climate adaptation: Examples from coastal Massachusetts’ smaller cities and towns. Journal of the American Planning Association, 80(2), 110–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.949590

- Hanna, E. G., Bell, E., & King, D. (2011). Climate change and Australian agriculture: A review of the threats facing rural communities and the health policy landscape. Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health, 23(2), 105S–118S. https://doi-org.proxy1.cl.msu.edu/https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539510391459

- Hart, P. S., & Feldman, L. (2016). The impact of climate change–related imagery and text on public opinion and behavior change. Science Communication, 38(4), 415–441. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547016655357

- Henly-Shepard, S., Gray, S., & Cox, L. (2015). The use of participatory modeling to promote social learning and facilitate community disaster planning. Environmental Science and Policy, 45, 109–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.10.004

- Houghton, A., Austin, J., Beerman, A., & Horton, C. (2017). An approach to developing local climate change environmental public health indicators in a rural district. Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2017, 1–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3407325

- Kahan, D. (2010). Fixing the communications failure. Nature, 463(7279), 296–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/463296a

- Kennedy, B. (2015). Describing and exploring cross-national public opinion on climate change (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, ProQuest Number 3726165), East Lansing, Michigan State University.

- Lal, P., Alavalapati, J. R. R., & Mercer, E. D. (2011). Socio-economic impacts of climate change on rural United States. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16(7), 819–844. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9295-9

- Lonsdale, W. R., Kretser, H. E., Chetkiewicz, C.-L. B., & Cross, M. S. (2017). Similarities and differences in barriers and opportunities affecting climate change adaptation action in four North American landscapes. Environmental Management, 60(6), 1076–1089. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-017-0933-1

- Marinucci, G. D., Luber, G., Uejio, C. K., Shubhayu, S., & Hess, J. J. (2014). Building resilience against climate effects – A novel framework to facilitate climate readiness in public health agencies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(6), 6433–6458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph110606433

- Marquette County Resource Management/Development Department. (2007). Hazard Mitigation plan for the county of Marquette, Michigan. https://www.co.marquette.mi.us/departments/planning/hazard_mitigation_plan.php.

- Measham, T. G., Preston, B. L., Smith, T. F., Brooke, C., Gorddard, R., Withycombe, G., & Morrison, C. (2011). Adapting to climate change through local municipal planning: Barriers and challenges. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change, 16(8), 889–909. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-011-9301-2

- Michigan Department of Health and Human Services (MDHHS) and Michigan State University Extension (MSUE). (2017, November 2). Marquette Area Climate and Health Adaptation Workshop, Meeting 1. PowerPoint presented at the November 2017 meeting of the Marquette Climate Adaptation Task Force (CATF), Marquette, Michigan.

- Michigan State University Extension (MSUE) and Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction (MSU SPDC). (2018). Marquette area climate and health adaptation guidebook – Volume I: Stakeholder engagement and visual design imaging. https://www.canr.msu.edu/climatehealthguide.

- Michigan State University Extension (MSUE) and Michigan State University School of Planning, Design and Construction (MSU SPDC). (2019). Marquette area climate and health adaptation guidebook – Volume III: Prioritizing and implementing recommendations. https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/marquette-area-climate-and-health-adaptation-guidebook-volume-iii-prioritizing-and-implementing-recommendations

- Mimura, N., Pulwarty, R. S., Duc, D. M., Elshinnawy, I., Redsteer, M. H., Huang, H. Q., Nkem, J. N., & Sanchez Rodriguez, R. A. (2014). Adaptation planning and implementation. In C. B. Field, V. R. Barros, D. J. Dokken, K. J. Mach, M. D. Mastrandrea, T. E. Bilir, M. Chatterjee, K. L. Ebi, Y. O. Estrada, R. C. Genova, B. Girma, E. S. Kissel, A. N. Levy, S. MacCracken, P. R. Mastrandrea, & L. L. White (Eds.), Climate change 2014: Impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Part A: Global and sectoral aspects. Contribution of working group II to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 869–898). Cambridge University Press. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap15_FINAL.pdf

- Morello-Frosch, R., Pastor, M., Sadd, J., & Shonkoff, S. B. (2009). The climate gap: Inequalities in how climate change hurts Americans and how to close the gap. https://dornsife.usc.edu/assets/sites/242/docs/The_Climate_Gap_Full_Report_FINAL.pdf

- National Research Council. (1996). Understanding risk: Informing decisions in a democratic society. National Academy Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17226/5138

- National Research Council. (2008). Public participation in environmental assessment on decision making. National Academy Press.

- National Research Council. (2010). America’s climate choices; Adapting to the impacts of climate change. National Academy Press.

- New York State. (2019). Climate Smart Communities (CSC). https://climatesmart.ny.gov/

- Nordgren, J., Stults, M., & Meerow, S. (2016). Supporting local climate change adaptation: Where we are and where we need to go. Environmental Science & Policy, 66, 344–352. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2016.05.006

- Ohio Department of Natural Resources. (n.d.). The great lakes basin. https://ohiodnr.gov/wps/portal/gov/odnr-core/

- O’Neill, S. J., Boykoff, M., Niemeyer, S., & Day, S. A. (2013). On the use of imagery for climate change engagement. Global Environmental Change, 23(2), 413–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.11.006

- O’Neill, S. J., & Nicholson-Cole, S. (2009). ‘Fear won’t do it’: Promoting positive engagement with climate change through visual and iconic representations. Science Communication, 30(3), 355–379. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547008329201

- Oulahen, G., Klein, Y., Mortsch, L., O’Connell, E., & Harford, D. (2018). Barriers and drivers of planning for climate change adaptation across three levels of government in Canada. Planning Theory & Practice, 19(3), 405–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2018.1481993

- Owrangi, A., Lannigan, R., & Simonovic, S. (2017). Development of a spatiotemporal composite measure of climate change-related human health effects in urban environments: A Metro Vancouver study. The Lancet, 389. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31128-5

- Pendall, R., Wegmann, J., Martin, J., & Wei, D. (2018). The growth of control? Changes in local land-use regulation in major U.S. metropolitan areas from 1994 to 2003. Housing Policy Debate, 28(6), 901–919. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1494024

- Raymond, C. M., & Robinson, G. M. (2013). Factors affecting rural landholders’ adaptation to climate change: Insights from formal institutions and communities of practice. Global Environmental Change, 23(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.11.004

- Rosser, E. (2006). Rural housing and code enforcement: Navigating between values and housing types. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 13, 33. https://ssrn.com/abstract=842584

- Runkle, J., Svendsen, E. R., Hamann, M., Kwok, R. K., & Pearce, J. (2018). Population health adaptation approaches to the increasing severity and frequency of weather-related disasters resulting from our changing climate: A literature review and application to Charleston, south Carolina. Current Environmental Health Reports, 5(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-018-0223-y

- Schramm, P., Uejio, C. K., Hess, J. J., Marinucci, G. D., & Luber, G. (n.d.). Climate models and the use of climate projections: A brief overview for health departments. https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/docs/ClimateModelsandUseofClimateProjections_508.pdf

- Schreck, B., & Vedlitz, A. (2016). The public and its climate: Exploring the relationship between public discourse and opinion on global warming. Society & Natural Resources, 29(5), 509–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2015.1095380

- Singh, N. P., Anand, B., & Khan, M. A. (2018). Micro-level perception to climate change and adaptation issues: A prelude to mainstreaming climate adaptation into developmental landscape in India. Natural Hazards, 92(3), 1287–1304. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-018-3250-y

- Smit, B., Pilifosova, O., Burton, I., Challenger, B., Huq, S., Klein, R. J. T., Yohe, G., Adger, N., Downing, T., Harvey, E., Kane, S., Parry, M., Skinner, M., Smith, J., & Wandel, J. (2001). Adaptation to climate change in the context of sustainable development and equity. In J. J. McCarthy, O. F. Canziani, N. A. Leary, D. J. Dokken, & K. S. White (Eds.), Climate change 2001: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. contribution of working group II to the third assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change (pp. 879 - 906). Cambridge University Press.

- Stults, M. (2017). Integrating climate change into hazard mitigation planning: Opportunities and examples in practice. Climate Risk Management, 17(C), 21–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2017.06.004

- Uittenbroek, C. J. (2016). From policy document to implementation: Organizational routines as possible barriers to mainstreaming climate adaptation. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 18(2), 161–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2015.1065717

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). (2013). Rural–urban continuum codes, 2013 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes/documentation

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (USDA ERS). (2015). Descriptions and maps: County economic types, 2015 edition. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/county-typology-codes/descriptions-and-maps/

- US Census Bureau. (2019). American factfinder: 2017 ACS 5-Year population estimate. https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

- USGCRP. (2018). Impacts, risks, and adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, volume II. Edited by D. R. Reidmiller, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, K. L. M. Lewis, T. K. Maycock, & B. C. Stewart. US Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA4.2018

- Weston, J., & Weston, M. (2013). Inclusion and transparency in planning decision-making: Planning officer reports to the planning committee. Planning Practice and Research, 28(2), 186–203. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.704736

- Winowiecki, E., & Williams, R. (2019, August 16). The federal government has been slow to act on climate change. So Michigan cities are taking charge. Michigan Radio. https://www.michiganradio.org/post/federal-government-has-been-slow-act-climate-change-so-michigan-cities-are-taking-charge

- Wisconsin Climate and Health Program. (2016). Climate and health community engagement toolkit: A planning guide for public health and emergency response professionals. Department of Health Services, Division of Public Health. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/publications/p01637.pdf

- Wood, R. S., Hultquist, A., & Romsdahl, R. J. (2014). An examination of local climate change policies in the great plains. Review of Policy Research, 31(6), 529–554. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ropr.12103

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). COP24 special report: Health & climate change. https://www.who.int/globalchange/publications/COP24-report-health-climate-change/en/

- Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. (2016). Global warming’s six Americas. http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/