ABSTRACT

The Covid-19 pandemic is the latest in a series of cascading crises of global capitalism that have both exposed and intensified a systemic problem of social and regional inequality that has in fact been unfolding in the advanced economies for more than four decades. There are growing calls for ‘rebuilding back better’ from the pandemic, for redesigning capitalism to make it more equitable and sustainable. This paper argues that regional studies has a key role to play in shaping and informing such an agenda, but that to do so requires a rethinking of our research priorities, theoretical frameworks and normative commitments. As part of such a rethinking, the paper calls for a progressive–melioristic turn in regional studies, for a transformative vocation committed to the pursuit of equitable and just regional outcomes.

INTRODUCTION: CAPITALISM AT A CRITICAL JUNCTURE

Crises and deadlocks when they occur have at least this advantage, that they force us to think. (Jawaharlal Nehru)

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. (Arundhati Roy)

Just over two decades ago, Ann Markusen complained that regional development studies had become too suffused with ‘fuzzy concepts’, too dependent on ‘thin empirics’, and too ‘distanced’ from policy relevance and impact (Markusen, Citation1999). Her critique received a mixed, but largely defensive, reaction, even from those of a heterodox bent (see the various responses in Regional Studies, 37, 2003, pp. 699–751). Whether or not those counter-arguments were valid, there is no doubt that since her thought-provoking paper, regional studies has advanced and improved on all three fronts: it has become more sophisticated and diverse in its theoretical frameworks, it has accumulated a rich body of empirical insights, and it has become more policy orientated and engaged. Yet, at the same time, in some quarters a sense of unease at the state of regional studies has not only rumbled on but increased, not least because of the continued growth of the spatial inequalities in economic prosperity and social welfare that were already well established when Markusen's paper appeared but which in many cases have actually intensified since. There is a concern that our theories and analyses provide only limited explanatory insight into this entrenchment of regional socio-economic inequalities and only partial policy solutions for their resolution (e.g., Hadjimichalis & Hudson, Citation2014; Martin, Citation2015).

Two historic events since Markusen's paper have served to throw the issue of regional social and economic inequalities into even starker relief. The Global Financial Crisis of 2007–08, driven in large part by the avarice of wealth-seeking banking and financial institutions concentrated in the world's major financial centres, resulted in an unprecedented bailout of banks by national governments that enabled the principal financial centres and their surrounding regions to bounce back well from the crisis and the Great Recession of 2007–09 it triggered. In contrast, the severe austerity cuts to public spending subsequently imposed by governments in order to reduce the dramatically increased levels of state debt incurred during the crisis and recession, were largely borne by poorer social groups and places, many of which are most dependent on those services (Gardner et al., Citation2020; for the case of the UK, see Gray & Barford, Citation2018). Little was done by governments to address the socially and spatially divisive effects of the crisis and its austerity aftermath.

Then, a decade later, in early 2020 the world was thrown into another crisis caused by the Covid-19 Global Pandemic, a global public health emergency on a scale not seen since the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918.Footnote1 As states have resorted to the repeated imposition of national and region-specific social and economic lockdowns in order to control the spread of the coronavirus, so their economies plummeted into a downturn that in many countries has been even deeper than that associated with the Global Financial Crisis.Footnote2 In some cases, the collapse of economic output has been the worst on historical record. States across the globe have expended huge sums of money to support workers, jobs and businesses in the lockdowns, amounting to more than three times the monies spent during the Global Financial Crisis.Footnote3 The poorest social groups – many with pre-existing health problems and inferior living conditions, within both the major cities and the least prosperous regions and localities – have figured among the most affected by the pandemic.Footnote4 Like the Global Financial Crisis before it, and from which many areas had still to fully recover, the Covid-19 crisis has highlighted and intensified social and regional inequalities that had been growing for at least the past three decades or so (e.g., Ascani et al., Citation2020; Coppola et al., Citation2020; Davenport et al., Citation2020; Hendrikson & Muro, Citation2020; McFarlane, Citation2020; Rose-Redwood et al., Citation2020). The impact of the pandemic has been to accelerate certain transformations of our socio-economies – transformations that many thought were going to take decades – and revealed that the capacity of different places to adapt to a ‘new’ world differs considerably.

In the space of just over a decade, the world economy has thus experienced two historic-scale disruptions that are only supposed to be ‘once-in-a-century’ events.Footnote5 The immediate and pressing current priority must be the public health task of recovering from the Covid-19 pandemic, and ensuring that the vaccines being made available are produced in sufficient quantity and administered equitably across the globe. This itself has already proved to be an enormous logistical challenge, and both the distribution and safety of the vaccines have become the subjects of geopolitical disputes and confrontations. But recovery from the pandemic, when it comes, will not mean that economies will emerge unscathed or unaltered, nor that they will simply return or ‘bounce back’ to some pre-pandemic ‘normal’ (Roy, Citation2020). Some of the changes in economic activity and organization and social behaviour wrought by the lockdowns imposed by various countries may prove to have more permanent effects. And to compound this issue, there is the ongoing and mounting climate-warming emergency, and the transformational social, economic and organizational changes that will be needed to mitigate and contain its effects. Given these various crises – of inequality, the pandemic and climate warming – there is a growing view that socio-economies should not simply return to some pre-Covid status quo ante, but that instead policymakers should take this opportunity to ‘build back better’. The task, however, is best viewed not simply as building back better, since that suggests a rather limited ambition: rather, the task should be to build forward better, to a new regime of economic and social development that tackles and surmounts the present cascade of crises.

This of course immediately raises questions of ends and means: what precisely is (or should be) this new ‘better’, and what sort of policies will be needed to ‘build’ it? In the remainder of this paper I briefly explore what such questions imply for regional studies, and argue that the current crisis of global capitalism behoves us to pause and take stock of our research aims and priorities. We have reached, it can be argued, another – though different and, in many ways, much more important – ‘Markusen moment’. It is my firmly held belief that a key motivation for regional studies, going forward, should be to direct considerable emphasis on how our discipline can help to ensure that societies ‘build forward better’ in a more progressive, socially, regionally and locally equitable, sustainable, and resilient way. This, I suggest, requires a shift in our intellectual paradigm based around a critical reflection on our existing body of theory and empirics coupled with a more explicit commitment to the principles of fair and just development; for what I call a melioristic turn in the discipline that brings those axiological and normative principles to the fore, and which connects regional studies closer to the world of the publics it studies. First, however, it is useful to briefly summarize the scale of the task.

THE GROWTH IN REGIONAL INEQUALITY

Economists have long argued that social inequalities in per capita incomes within a country first rise and then decline as its economy grows (the ‘Kuznets curve’), and similarly that regional inequalities in economic prosperity should show a similar downward trend as countries get richer (the ‘Williamson curve’). Although this had been true over the decades from the late 1930s to the late 1970s, since the early 1980s social and spatial inequalities have increased and become entrenched in many advanced economies: convergence has been replaced by divergence. Within society it has been the highly educated, skilled, technical and professional groups that have seen their real incomes increase significantly, while other groups – the less educated and less skilled, and those in manual occupations – have lagged behind. Whatever measure is used, the gap between the upper tiers of the income distribution and those in the lower tiers has widened (Atkinson, Citation2015; Atkinson et al., Citation2017; Lakner & Milanovic, Citation2016; Piketty, Citation2015; Stiglitz, Citation2015).

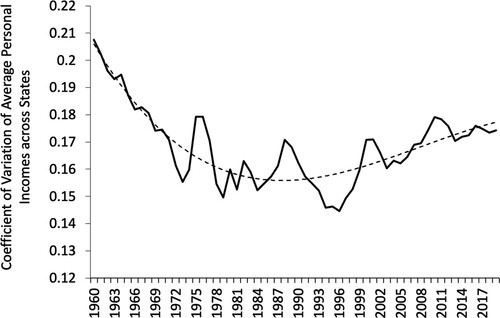

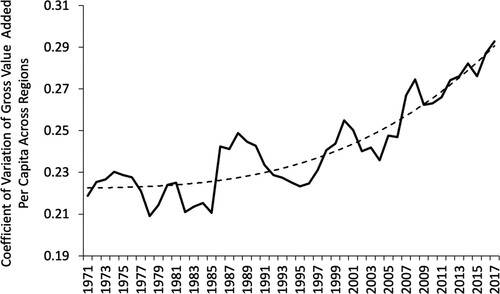

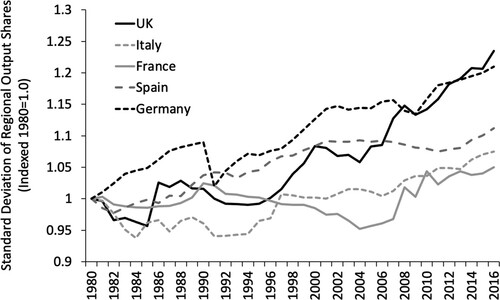

Likewise, regional economic inequalities have increased in many advanced economies since the early 1980s. Certain regions, cities and localities have ‘pulled ahead’ in terms of economic prosperity, while many other regions, cities and localities have failed to keep pace, and have been ‘left behind’ (Hendrikson et al., Citation2018; Iammarino et al., Citation2019; Rosés & Wolf, Citation2020; Storper, Citation2018).Footnote6 Meanwhile, the future of those places in the ‘middle’ is by no means clear, and many of which could – as Moretti (Citation2012) puts it – go either way. While the precise extent of the widening varies with geographical scale, and from country to country, a broadly similar trend appears to have been at work across several of the advanced economies. show examples using various indicators for the United States, the UK and selected European countries.

Figure 1. The end of regional convergence and the switch to regional divergence in the United States: the coefficient of variation of nominal average per capita incomes across states, 1960–2019. Source: Author’s own calculation of data from the US Bureau of Economic Analysis (https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/index_regional.cfm).

Note: The fitted trend is a third-order polynomial.

Figure 2. Growth in regional inequality in the UK: the coefficient of variation of gross value added (GVA) per capita across standard NUTS-1 regions (in 2016 prices), 1971–2017. Source: Author’s own calculation of data from Cambridge Econometrics and the UK Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Note: The fitted trend is a third-order polynomial.

Figure 3. Increasing disparity in regional shares of national output in selected European countries: standard deviation of regional shares of national gross value added (GVA) (NUTS-1 regions, 2016 prices), indexed 1980 = 1.0. Source: Author’s own calculation of data from the Cambridge Econometrics European Regional Database.

Note: West Germany up to 1990, unified Germany thereafter.

More generally, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD):

Within their own borders OECD countries are witnessing increasing gaps in GDP per capita between higher performing and lower performing regions. … The gaps within countries between the top 10% regions with the highest productivity and the bottom 75% has grown on average by about 60% over the last two decades. (OECD, Citation2016, p. 26)

It is remarkable that the emerging picture on regional inequality in the long-run is also similar to the pattern of inequality in terms of personal income and wealth distributions … the pattern of regional inequality [in Europe] over the last 110 years follows a U-shape, just like the pattern of personal income inequality … after 1900 we find a spread of economic activity across regions and convergence until about 1980, and divergence as well as geographical re-concentration thereafter. (pp. 35–36)

This suggestion that there exists a link between the need to rethink the economy, the growth in regional inequality, and the issue of political stability, is well made. The extent of regional socio-economic polarization has reached a level that politicians and policymakers can ill-afford to ignore. Across several of the advanced OECD countries, the voting populations in ‘left behind’ jobs and ‘left behind’ places either feel forgotten by mainstream politicians and their policies, or at worst deliberately neglected by them in favour of the more prosperous places and the metropolitan centres where national political and economic elites themselves are typically concentrated. The electorates in many ‘left behind’ places have used the ballot box as a chance to express their discontent and reverse their lagging fortunes. While the recent rise of political populism in many countries has many causes, and has involved new movements on both the right and left of the political spectrum, there is no doubt that some such movements can be seen, in part at least, as expressions of social discontent by those living in the places forgotten and bypassed by the economic progress of recent decades (Hendrikson et al., Citation2018; Rodriguez Pose, Citation2018). In the United States, Donald Trump owed his surprise 2016 presidential election success in part to his playing to this geography of ‘abandoned places’, with his promises to ‘bring jobs back’ to the country's economically lagging towns and cities.Footnote7 In the UK, both the Brexit vote in 2016 and the electoral victory of Boris Johnson as Conservative Prime Minister in 2019 were driven by support from the traditionally Labour-voting ‘left behind’ places (the so-called Red Wall) in Northern England. ‘Levelling up’ the economic geography of the country has become a key political mantra.Footnote8 In several other instances social discontent has taken the form of direct civil protest and disobedience, as in the ‘Gilets Jaune’ in France, and the ‘Fora Bolsonaro’ and ‘Impeachment Ja’ movements in certain cities and regions of Brazil.

What the Global Financial Crisis and especially now the Global Covid Pandemic have done is to highlight a systemic problem of socio-economic and regional inequality that has been unfolding for some time, and which has to do with the very nature of the regime of global capitalism that developed over recent decades. If ‘rebuilding forward’ from the Covid pandemic is to reduce regional socio-economic inequalities, it will need to be based on a major rethink of that regime (Georgieva, Citation2020) – and possibly of our theories of regional development.

RESETTING CAPITALISM: BUILDING FORWARD BETTER

History suggests that major crises in the development of capitalism provide critical junctures for taking stock of our views of the world, of dominant approaches for understanding that world, and of our ideas on how to improve it. This was precisely what happened in response to the Great Crash and Depression of the interwar years and immediately following the Second World War itself. Economic theory underwent a major rethink, pioneered particularly by Keynes’ arguments that economies are not automatically self-righting following major disruptions, and that states have a key role to play – especially by means of government fiscal measures – in fostering recovery as well as managing and smoothing the business cycle. This helped to drive a new post-war social-democratic model of economic growth and governance – a new social contract – within the advanced economies, founded on an interventionist state and social welfare programmes at home, and a regulated financial and trading system internationally (especially Bretton Woods), a combination that helped to forge three decades of steady and stable economic development and full employment. It was no accident that social and spatial inequalities narrowed under this new model.Footnote9

It is also surely no accident that the subsequent unwinding and abandonment of that post-war consensus in many advanced economies from the late 1970s onwards, in favour of a neoliberal economic model based on marketization, commodification, financialisation and rampant globalization, has been accompanied by the widening of social and spatial inequalities.Footnote10 It is this model that has now so patently failed and is in need of replacement (Coates, Citation2018). We now stand at another critical juncture in the organization and development of capitalism. As Rodrik (Citation2018) so clearly states of the issue:

If capitalism is to survive it must be redesigned to address the multitude challenges of globalization, inequality (both national and international), rapid technological change, climate change, and democratic accountability under which it reels at present. … How can public policy be more effectively deployed to stimulate green technologies? How can the unequalizing forces of technological innovation be harnessed for greater equity and social inclusion? How can globalization be reformed to enhance both domestic and international inequality despite the apparent tension between the two? How can progressives develop a politically-winning agenda that overcomes the appeal of populist demagogues? (pp. 202–203)

Putting aside budget constraints, we have just seen that the pre-pandemic ‘normal’ had dire implications for the world. Our strained interactions with the environment helped introduce the coronavirus to humans, our hyperconnected global economy allowed it to spread like wildfire, and its especially deadly effects on the most vulnerable populations have highlighted the consequences of deep-seated social and economic inequalities within and between countries. Instead of aiming to restore that pre-2020 way of life, our leaders should set their sights on creating a different, better world.

Take the issue of globalization. There are obvious benefits of globalization, of increased economic, technological, social and cultural interaction, interdependence and exchange between nations. Globalization and trade have helped lift millions out of poverty in developing and emerging economies.Footnote11 Close cooperation, collaboration, and coordination between nations and governments is needed on several fronts to promote fair trade, to stabilize financial markets, to control the power of global monopolies, to help fight global pandemics (as the development of Covid-19 vaccines has demonstrated) and to prevent global climate change (through internationally agreed carbon emission reduction agreements, such as the Paris Accord of 2015). But at the same time, the largely unregulated globalization of recent decades has had substantial costs and downsides, including, among others, an increasingly unbalanced pattern of global trade, itself a key cause of the Global Financial Crisis (Pettis, Citation2013); substantial negative environmental and climate impacts associated with the rapid growth in global trade and supply chains;Footnote12 the exploitation by global corporations of workers in low-wage countries; the increased fragility and vulnerability of production networks and supply chains that have become overly dispersed and stretched globally (McKinsey Global Institute, Citation2020); the ability of major global corporations and monopolies to move their activities around the globe with little regard for the impact on local communities; and similarly the ability of those major global companies to employ complex offshore profit shifting and tax avoidance strategies.Footnote13 Many of these developments have contributed to the problem of regionally divergent growth in the advanced economies.

While financial globalization certainly helped fuel the rapid economic growth and concentration of wealth in the major financial centres and capitals of the advanced economies it did little to boost other cities and regions, many of which were then severely impacted by the credit squeeze during the Global Financial Crisis and the austerity programmes that followed. Meanwhile, there is evidence that rapidly growing import penetration from lower cost countries (especially China) and the offshoring and outsourcing of activities and supply networks to the latter have contributed to the disruption of local industrial ecosystems and the loss of manufacturing jobs in many localities within the advanced economies (Autor et al., Citation2013; Rudiger, Citation2007; Scott & Kimball, Citation2014).Footnote14

The proper response to these and other destabilizing effects of what Rodrik (Citation1998) calls ‘hyperglobalisation’ is not protectionism nor nativist impulses, but whether we can globalize better and more equitably (OECD, Citation2018; Rodrik, Citation2018). After all, rampant unrestrained globalization is not some ineluctable force of nature, ‘out there’ like gravity, to which regions, cities and localities – and governments – have no option but to bend,Footnote15 but is in large part a political construction, shaped by the values and ideologies of individual states, global institutions and today’s global corporations. The untrammelled pursuit of hyperglobalization by financial, corporate and technological elites makes it difficult to achieve social and regional inclusion at home (Gray, Citation1998). What is needed is a new global agenda founded on new ground rules on finance, trade, the regulation and taxation of global corporations,Footnote16 environmental standards, and labour standards, all underpinned by a commitment to foster economic localization (e.g., Hines, Citation2000).

Likewise, another challenge is to make technological change, another of the ‘big processes’ driving global capitalism, more socially and locally inclusive. Schumpeter saw technological change as a key driver of ‘creative destruction’ and economic–industrial mutation. But history indicates that industrial–technological revolutions, if left to their own logics, need not be socially or spatially neutral in their creative and destructive effects. Instead, they tend to widen social and spatial inequalities. The latest revolution – the so-called Fourth Industrial–Technological Revolution, driven by artificial intelligence, robotics, new materials, advanced digital platforms and medical technologies – if left to the market is not likely to be any less socially and spatially divisive in its consequences for jobs and incomes: indeed, there are signs that this is already happening. We understand and celebrate the role of ‘brain hubs’, ‘star cities’, ‘high-technology clusters’ and the like in driving technological advance. But we know less about and have directed less attention to investigating how to spread the prosperity-creating and social benefits of technological change more evenly and equitably across regions, cities and localities, whilst simultaneously mitigating the local impact of the disruptive and destructive effects of such change. A key aspect of this relates to the local impacts of the technological transition to a green, net-zero carbon economy. In building forward to such an economy, it will be imperative to ensure that the transition is a social and spatially just one, that it does not just favour existing technologically innovative places or the richer sections of society, but provides a means of reviving and rebuilding places whose carbon-based economies will need to be reorientated the most.

Then there is the issue of cities, especially big cities. Both academic work and policy discourse has become obsessed with the advantages of large and dense cities, and with agglomeration. Of course, cities confer all sorts of positive externalities that promote prosperity. But do those benefits simply increase linearly with city size and city density? The Covid-19 pandemic has struck at the heart of cities, with an estimated 90% of confirmed cases worldwide reported in urban areas. High rates of population and business density, cultural and social gatherings, public transportation, mass in-commuting, the intermingling of diverse business and creative networks – many of the traits that define the uniqueness and advantages of cities – have also proved to be vulnerabilities and to weaken economic resilience. And while big cities may have higher overall productivity, they do not always score the most highly in terms of quality of life or life satisfaction. The shift to online retailing and e-commerce, accelerated by the pandemic, is likely to continue post-Covid, as is the shift to homeworking amongst city office workers that has occurred during the lockdowns.Footnote17 None of this even remotely suggests of course that the age of urbanization is over or that agglomeration in unimportant: cities are indispensable to human progress. But perhaps now is the time to reimagine our cities, their role, structure and layout, to highlight the social, environmental and health benefits of lower density and substantial greening, as well as the advantages of smaller cities, many of which are just as economically dynamic and resilient as large cities, if not more so.Footnote18

And then there is the state, and the nature of state–economy relations. Both the Global Financial Crisis and especially the Covid pandemic have triggered a return of large-scale state spending and activism in an effort to allay the immediate social and economic impacts of these massive shocks. Yet more spending and support will be needed to rebuild economies out of the pandemic, and it is imperative that this spending is directed to reducing regional inequalities.Footnote19 Full recovery from the pandemic will not necessarily occur quickly, and certainly the huge public debt overhang is likely to persist for some considerable time. It is crucial that states do not then seek to reduce debt levels through another round of fiscal austerity (Kose et al., Citation2020), given the enormous damage to public services, especially in less prosperous regions, cities and localities, wrought by the austerity programmes pursued in the decade following the Global Financial Crisis.

Given that the costs of borrowing are at an all-time historic low, states have a major opportunity to rebuild their economies by upgrading infrastructures, investing in green technologies, in public health facilities, in social care and related services, in labour skilling, and support for business and innovation. As Mazzucato (Citation2013, Citation2018, Citation2021) has so strongly argued, the time has come for a new discourse on the role of the state, of government activity and the public sector as productive and foundational to creating a dynamic and fair capitalist economy. As part of this new discourse, there is a need to consider how central government activity can be harnessed, in collaboration with, and by devolving more power to, local state authorities, to renew, reorientate and level up the economies of ‘left behind’ places. By and large, central states have neglected the untapped social and economic potential that exists in such places, in favour of a political preoccupation with promoting their global ‘star’ cities, the assumption being that the benefits of these national economic ‘dynamos’ will sooner or later trickle down to the rest of the urban and regional system.Footnote20 The evidence for such ‘trickle down’ effects is questionable, however. What is just as likely is that the concentration of economic, financial, and corporate power in global ‘star’ cities exerts considerable self-interested influence over the activities and policies of the central state, which itself is often based in such cities. In effect, central governments can become ‘captured’ by their global ‘star’ cities, imparting a spatial bias to what are ostensibly non-spatial national policies.Footnote21 A key debate is needed over what division of powers and policies between the central state and local state would best promote inclusive and sustainable development.Footnote22

In every one of these and related big questions, there are profound implications for regional development and the role of policy, and thus a major opportunity for the discipline of regional studies to help shape the new discourse on both.

RESETTING REGIONAL STUDIES

A basic question, then, is this: if the need to ‘rebuild better’, to ‘redesign capitalism’ to use Rodrik's phrase, in a way that is regionally just and equitable, is accepted, do we need to rethink our research priorities, our theories and our empirical foci in order to help secure that objective? Put another way, do we need to (re)examine what we are doing in regional studies, why are we doing it, and for whom? Just as there are growing calls for a rethinking of other key social sciences, such as economics and sociology, in order to put them to the service of a better world (e.g., Krecké, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2019; Raworth, Citation2017; Rochon & Rossi, Citation2017; Turner, Citation2012; Streeck, Citation2016, ch. 11) should we not at least discuss whether regional studies likewise needs to be redrawn and reframed, and if so, how?

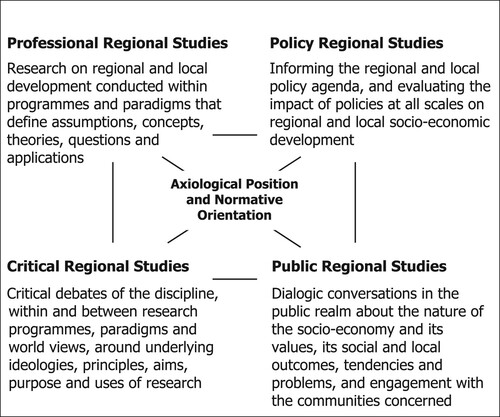

Fundamentally, this requires us to re-examine what sort of knowledge we are producing in regional studies, and what the audiences are for whom we are producing it. Burawoy (Citation2005, Citation2016, Citation2021) suggests that in social science a distinction can be made between two main types of knowledge, instrumental and reflexive, and two basic audiences, the academic–professional and the extra-academic. Although his discussion has referred specifically to sociology, his schema can be usefully adapted to distinguish between four ‘types’ of regional studies (): professional regional studies, policy regional studies, critical regional studies, and public regional studies. Although each can be categorized by its particular knowledge/audience combination, they are not independent of one another, but inextricably interrelated. Further, each of these types of regional studies is bound up with underlying axiological, normative and ideological dispositions and presumptions, even if hidden from view.

Figure 4. Dissecting regional studies: types of knowledge and audience.

Note: Based on and adapted from the discussions made in Burawoy (Citation2005, Citation2016, Citation2021).

The overwhelming focus in regional studies over recent decades has been on developing our body of instrumental knowledge, our research paradigms, theoretical frameworks, and explanatory methods and techniques. The aim is to understand regional socio-economic phenomena, and political views are normally excluded from research procedures and interpretations. The primary purpose is to write for other academics – for one another – and to advance within the academic community.Footnote23

It is this body of knowledge that has formed the basis for how regional studies has sought to inform, promote and evaluate particular regional development policies. No doubt it could be argued that our corpus of instrumental knowledge already provides us with the tools to address the question of how we might move to a model of capitalist growth that is more regionally and socially equitable. After all, seemingly, we have a good idea about what makes for a prosperous and productive region, city or locality – for example, a highly skilled workforce; good physical, soft and social infrastructures; a thriving entrepreneurial culture; clusters of technologically innovative firms; an industrial ecosystem of related economic activities; good connectivity; and good governance and leadership. It is then tempting to turn 180 degrees, as it were, and argue that what is therefore needed to reduce regional inequalities are policies aimed at promoting these very same characteristics in the economically lagging or ‘left behind’ places, and further that those policies should be ‘place-based’, since the precise growth characteristics or ‘drivers’ needing development will vary from one place – one region, city or locality – to another.Footnote24

Perhaps, then, it might be thought that only relatively minor or marginal adjustments and additions to our existing theories and approaches are needed in order to respond to the new challenges of our times, rather than embarking on a major rethink and reorientation of our discipline. However, the sobering irony is that while our theoretical and empirical accounts of regional development have expanded and become ever more sophisticated, regional inequalities have continued to increase and become entrenched. It could be argued, of course, that this is due not to our theories and the policy ideas based on them, but to the failure of governments and other policy bodies to properly implement or adequately resource those policy ideas: regional studies scholars can hardly be blamed if governments have not accorded regional and urban policies the importance they deserve, and have treated them more as marginal ‘add-ons’ to their primary, macro-economic concerns.

But is regional studies wholly without blame? Do we not bear some responsibility for the limited impact of the plethora of policy ideas that we have offered policymakers over the past four decades or so? Clearly it is unrealistic to expect perfect equality of per capita incomes, employment rates, and so on, between regions or cities: capitalism is too dynamic for that to happen, and there will always be differences in economic and social structures between places. But we still lack a surprising degree of consensus within regional studies, economic geography, geographical economics and regional science over how best to measure spatial socio-economic inequality (what the key metrics are); what might be an acceptable level of spatial inequality; what its implications are (for not only localities themselves but also for the national political socio-economy); how to explain it (most of our theories are partial in focus), and how best it can be minimized (what policies are needed and at what spatial scales).

Our existing body of instrumental knowledge was itself largely built up under, and in response to, the very model of capitalist development that has produced the problem of regional inequality that now urgently needs solving. To be sure, there is a growing and welcome interest in regional studies in identifying the implications of new challenges, such as the transition to net zero carbon modes of growth, and the impacts of the new artificial intelligence revolution. And the notions of inclusive growth, the circular economy, and the foundational economy are likewise receiving increasing attention. But such emerging important themes tend to reinforce the need for a fundamental shift in the core foci and underlying principles of our research agenda as a whole, rather than just adding these issues to our existing paradigms as new empirical developments and problems requiring analysis. To compound matters, the focus of our theoretical and empirical effort has disproportionately centred on ‘successful’ regions and cities, and much less attention has been given to less prosperous ‘left behind’ places (e.g., Donald & Gray, Citation2019; Hadjimichalis & Hudson, Citation2014; Martin, Citation2015). Yet further, our explanations of spatial socio-economic inequality are rarely holistic, but tend to focus on this or that particular feature or cause, and are often overly locally based when the real causal processes and structures at work reside at deeper systemic levels that have to do with the very logics of contemporary capitalism.

In rethinking our priorities and purpose in regional studies, we almost certainly have to confront the normative underpinnings and orientation of our work. Normative issues are central to the production of reflexive knowledge. The latter has to do with dialogues and conversations about ends, not instrumental means, about underlying views of the world, its events and purpose, our axiological positions, and what normative values we deem to be important. Normative questions are not much discussed in regional studies, but our values and axiology are in fact foundational, even if we do not acknowledge them: our values influence our research priorities, the sort of research questions we ask, and how we think the world should be organized (). Reflexive dialogues about regional studies knowledge should not only take place within our academy itself, but also between our academy and the various extra-academic audiences and publics (the local, national, and even international communities) on which our research is conducted, to which it applies, and to which it is, ultimately, accountable. Reflexive knowledge interrogates the value premises of our discipline as well of society itself. Public regional studies is the conscience of policy regional studies, exposing the means-end rationality upon which it rests.

We are surely at a time when that means-end rationality and our value premises require critical reflection. This, I would argue, should mean regional studies scholars taking a much more explicitly progressive stand against spatial socio-economic inequalities and striving through their theoretical, empirical and public engagement for fair and equitable regional and local outcomes. Of course, a concern with spatial socio-economic disparities has long been the primary focus of regional studies, economic geography and regional science: one might say their very raison d’être. Mapping and explaining regional socio-economic disparities is central to what we do. The ‘critical regional studies’ of the late 1970s and 1980s went beyond that endeavour, however. That body of work was explicitly concerned with capitalism as a process of combined and uneven social and regional development, how if left to its own devices capitalism simultaneously produces both economically successful and less successful places, and moreover argued that the production of the former depended in various ways on the exploitation of the latter. It was critical in the sense that it was concerned with revealing the social and spatial injustices of economic accumulation, and the formative logics, contexts and structures that underpin that process; and progressive in that it argued for major, radical reform of those formative logics, contexts and structures. While there are certainly some who continue to champion a critical approach to regional studies, and some who also engage in local activism, the reality is that for the most part the radical, progressive edge to our discipline has been largely submerged, even subverted, by the proliferation of diverse theoretical and technical specialisms dealing in evermore detail with narrowly defined and overly economistic–technicist aspects of regional development. Perhaps not surprisingly, many of the expanding array of ‘spatial policy solutions’ that have spiralled out of regional studies in recent years (clusters, regional innovation systems, smart specialization to name but a few) have likewise been partial; few direct a critical lens on the systemic contradictions and instabilities of contemporary capitalism.

An explicitly critical–progressive stance in regional studies calls for a firm and public commitment to a more melioristic discipline. By meliorism here I mean an openly proclaimed normative and axiological position that existing conditions of social and spatial inequality are unacceptable and can and must be improved through appropriate purposive analysis, debate and persuasion, a position that encourages us to critically interrogate the forces that produce regional inequalities, to expose the obstructions to a fairer and more equitable spatial distribution of socio-economic outcomes, and to undertake the research and engagement to overcome those obstructions. This will mean asking penetrating and difficult questions that challenge the formative processes and structures of our time: about globalization, global value chains and production networks, trade, large corporations, technological systems and advance, urbanization and the role of cities, about what is meant by productivity, about inclusion, the role of the state, about the use of environmental resources, about the politics of local economic development, about local democracy, and much more.

Crucially, it will also necessitate a rethinking of what we mean by value, and how we measure it. Rethinking the meaning of value is emerging as a major issue in the social sciences (Mazzucato, Citation2018; Narotsky & Besnier, Citation2014). The monetization and marketization of ever more aspects of social and cultural life, of the public sphere, and of the environment, has resulted in defining their usefulness, purpose and value in terms of the narrow calculus of price rather than in terms of their beneficial contributions to well-being, quality of life and sustainability, all of which need to be properly recognized in assessing and comparing regional ‘development’ and local ‘prosperity’. To create fairer societies and more equitable economic geographies we need to initiate a vigorous debate in regional studies about the nature, origins and distribution of value in all its forms.

A progressive and melioristic regional studies needs to articulate an unassailable case for reducing spatial disparities in incomes, employment opportunities, health, education, housing, productivity, and wellbeing. That case is simultaneously social, economic and political. It requires us to foreground and elevate the principles of social justice in our theoretical, empirical and policy enquiries. Defending territorial equality on social justice grounds is based on the democratic imperative to create a society where every citizen, regardless of where they happen to reside, has a fair chance of a decent life. Individuals should not be seriously and systematically socially disadvantaged with respect to job opportunities, housing conditions, health outcomes, access to public services, environmental quality, and the like, simply by virtue of living in one region rather than another. The political argument has to do with ensuring the social and political foundations for a stable and representative democracy: the larger are spatial socio-economic inequalities, the greater the risk of local political disillusionment and disaffection. The economic case for reducing spatial inequalities rests on refuting the pernicious and frequently made argument that there exists some sort of ‘trade-off’ between regional equality and national growth and efficiency (Martin, Citation2008), that the pursuit of the former undermines the latter, and that resources should therefore be allowed ‘to follow the market’ and concentrate in the leading growth regions where returns are higher. In practice, the success of leading regions is not simply the outcome of ‘efficient market forces’, but is often significantly underwritten by large state expenditures and subventions (e.g., on infrastructure).Footnote25

What might a more progressive critical regional studies have to say to a contemporary public that is more worried than it has been in a long time about where contemporary capitalism is going, and particularly to those living in places that have been by-passed by the mainstream of economic prosperity? At a minimum it should be able to impress on the public consciousness that the causes of having been ‘left behind’ are not to be found simply in the ‘market failures’ beloved of economists and most policymakers, but in the basic processes and structures of democratic capitalism as it has developed since the Second World War, and especially since the late 1970s. It should be able to provide a convincing narrative as to how present spatial socio-economic inequalities can be reduced, and to demonstrate that this will require more than a plethora of piecemeal and ad hoc spatial policy interventions, and nothing less than a new model of growth and development that treats each region, city, town, and local community as being of equal importance to the performance and cohesion of the socio-economy as a whole. At a time when national democracies have become fractured and untrusted, the public role of a progressive regional studies could not be more important.

CODA: REGIONAL STUDIES AS TRANSFORMATIVE SOCIAL SCIENCE

The current conjuncture provides a critical point of departure for an intellectual enterprise that labours for a new economic–political regime capable of reducing social and regional inequalities. The discipline of regional studies has a key role to play in that task, a role in which progressive melioristic priorities should dominate. To elevate meliorism as our guiding principle will require us to escape the intellectual path dependence that has shaped the development of our discipline over the past four decades, and to venture into new ways of thinking centred around a sense of programmatic mission and transformative vocation. By this I mean finding transformative opportunity in the midst of crisis, by developing a credible view of resolving regional socio-economic inequalities that frees us from the temptation to describe as realistic only those theoretical approaches and policy recommendations that stick close to our current knowledge and practice.

Constructing new theories, interpretations and explanatory frameworks – new professional instrumental knowledges founded on radical progressive imperatives – will allow us to be bolder and more innovative in our policy analyses and advice. Critical, reflexive thinking will be essential to this endeavour. But equally, regional studies will need to transcend the academy to cultivate greater collaborative interaction and engagement with the social and civil realms both to inform public debate about regional and local socio-economic inequalities and the reasons for those inequalities, and to be better informed about the grievances and aspirations of those social groups and places that have been ‘left behind’. Regional studies needs to (re)cultivate its critical imagination, to expose the gap between what is and what could be, to infuse social value into the discipline, and to remind us that the world can be rebuilt better.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This paper is an expanded and redrafted version of the short Address that I would have given at the Regional Studies Association’s Winter Conference in London in November 2020 to mark the end of my term as President of the Association. Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, that conference had to be cancelled, and instead the text of my Address was posted as a blog on the Association's website. I am grateful to Sally Hardy and Mark Tewdwr-Jones who encouraged me to expand that blog into this contribution, and who made valuable comments on an earlier draft. Of course, they bear no responsibility for the arguments expressed herein; nor do those arguments necessarily reflect the views of the Association. I am also grateful to two anonymous referees, the Editor Stephen Hincks, and to colleagues Professors Andrés Rodriguez Pose and Peter Sunley, for their perceptive and helpful comments on an earlier draft. They too, of course, bear no responsibility for the final outcome.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Although this is the name given to the H1N1 virus pandemic of 1918–19, there is no universal consensus regarding where it originated. Some of the earliest cases were in fact in the United States.

2 In most countries the drop in gross domestic product (GDP) in the second quarter of 2020 was dramatic. Compared with the same quarter in 2019, GDP fell by 12.4% in the Eurozone, by 10.4% in the G7 and by 10.5% in the OECD (Economic Indicators, No. 02784, January 2021, House of Commons, UK).

3 It is estimated that globally more than US$12 trillion has been committed. Some US$4 trillion of this has been in Western Europe alone, amounting to almost 30 times today’s value of the Marshall Plan for post-war reconstruction.

4 One of the most disturbing aspects of the pandemic is how the burden of infection risk has been disproportionately borne by precisely those groups of frontline and key workers on whom the functioning of society and the economy most depends, but who are among the lowest paid (those working in many sections of healthcare, social care, in public utilities and services, public transport, supermarkets, postal and delivery services, and logistic activities). It is to be hoped that one of the outcomes of the Covid crisis, and an urgent aspect of ‘building forward better’, will be a proper societal, economic and political recognition of the value, suitably rewarded, of these foundational groups in the labour force.

5 Of course, there have been several economic and other crises over the past century, both national and global in reach; but both the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–08 and the current Covid pandemic have been directly compared in scale and impact with their historical precedents of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918 and the Great Crash of 1929.

6 The distinction between ‘pulling ahead’ and ‘left behind’ is but the latest academic and political nomenclature used to characterize the issue of territorial socio-economic inequality or geographically uneven development. The problem with this terminology is that it can all too easily be used by politicians to celebrate the ‘success’ of the ‘pulling ahead’ places as exemplifying what ‘left behind’ places need to do to enjoy similar success, and to use such slogans as ‘levelling up’ the ‘left behind’ places as a way of securing the electoral support of their voters (see below).

7 ‘In many parts of our country, the hard times never seem to end. I’ve visited cities and towns in upstate New York where half the jobs have left and moved to other countries. Politicians have abandoned these places all over our country and the people who live there. … I am running to be their voice, and to fight to bring prosperity to every part of this country’ (Donald Trump, Presidential Campaign speech on jobs and the economy, 15 September, 2016) (see also note 6).

8 As in the Conservative government's ‘New Deal’ plan for recovery from the Covid recession (see also note 6):

[T]oo many parts of this country have felt left behind. Neglected, unloved, as though someone had taken a strategic decision that their fate did not matter as much as the metropolis [London]. So I want you to know that this government not only has a vision to change this for the better. We have a mission to unite and to level up. … . To mend the indefensible gap in opportunity and productivity and connectivity between the regions of the UK. … We will not just bounce back. We will bounce forward – stronger and better and more united than ever before. (Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Speech on New Deal for Britain, 30 June 2020).

9 The post-war Keynesian–welfare state model of economic accumulation and regulation, and universal education and healthcare provision, had several national variants, and was not without its problems, of course. Nevertheless, in most countries post-war Keynesian–welfarist-type interventionism was a key factor making for social and regional convergence in economic outcomes (Martin & Sunley, Citation1997).

10 To be sure, this shift to neoliberalism varied in degree and specifics from country to country (hence, ‘varieties of neoliberalism’). But the overall ‘direction of travel’ was similar, to a mode of economic governance that altered the balance of state–market relations under the Keynesian–welfarist model away from the state in favour of the market. What the notion of ‘varieties of neoliberal’, like its close relative ‘varieties of capitalism’, downplays is the interdependence of national economies in the global capitalist system, an interdependence that has dragged various states in the same overall direction. Indeed, Streeck goes as far as arguing that longitudinal commonalities should receive greater emphasis that cross-sectional (i.e., between state) differences (Streeck, Citation2016, pp. 221–225).

11 Underdeveloped and developing countries benefit from globalization because the increased trade, financial flows and technological diffusion involved should all raise investment, wages and employment, and stimulate local wealth creation, in those countries. While this has certainly happened in some cases, in other developing countries, however, globalization has not been as beneficial as predicted (Rodrik, Citation1998; Rodrik & Subramanian, Citation2009).

12 It has been estimated that the typical consumer company’s supply chain creates far greater social and environmental costs than its own operations, accounting for more than 80% of greenhouse gas emissions and more than 90% of the impact on air, land, water, biodiversity and geological resources (McKinsey Global Institute, Citation2016).

13 Global corporations – including the giant info-tech companies – have perfected the art of tax avoidance using complex mixtures of debt shifting, tax havens to register intangible assets, and transfer pricing strategies. Through such devices, these companies accumulate wealth by using places to extract value which is then sheltered elsewhere in a few favoured locations. It has been estimated that multinational companies shift over US$400 billion in profits out of 79 countries each year. This equates to about US$125 billion in lost tax revenue in those countries (see https://descrier.co.uk/business/how-multinational-corporations-avoid-paying-hundreds-of-billions-of-dollars-in-tax/), the governments of which could otherwise use to provide essential public services and infrastructures.

14 Sandbu (Citation2020) argues that technological change and policy failures have been more important than globalization in explaining the loss of manufacturing employment in the advanced economies. Technological change and policy failures have indeed played their part, but both of these have themselves facilitated and encouraged a largely unregulated process of globalization.

15 There have been some explicit statements by major political leaders to the effect that globalization is inevitable and unstoppable. Tony Blair’s 2005 speech to the British Labour Party is emblematic of this view: ‘I hear people say we have to stop and debate globalization,’ Blair told his party. ‘You might as well debate whether autumn should follow summer.’ There would be disruptions and some might be left behind, but no matter: people needed to get on with it. Our ‘changing world’ was, Blair continued, ‘replete with opportunities, but they only go to those swift to adapt, slow to complain’ (speech to the Labour Party Conference, 27 September 2005).

16 See note 13.

17 It has been estimated that up to 30% of workers in cities could work from home, either full- or part-time, without any loss of productivity. Most of such workers are in knowledge-intensive, professional, finance and business services (see https://blogs.deloitte.co.uk/mondaybriefing/2020/10/home-working-and-the-future-of-cities.html).

18 The productivity gains from a doubling of city (employment or firm) density have been estimated to be around 3–8%, which by any calculation is modest indeed. Such estimates rarely take fully into account the diseconomies associated with pollution, congestion, strains on local public infrastructures, higher rents, housing and land costs, and loss of quality of life, that a doubling of city density would be likely to entail.

19 In the United States, for example, the scale of the fiscal stimulus considered necessary to build economic recovery is of historical proportions, with the new Biden administration’s American Rescue Plan, a US$1.9 trillion package to boost consumer spending (equivalent to 9% of national income), and the possibility of a further US$3 trillion for infrastructural investment. How much of the fiscal stimulus will go to boost US jobs and industry, and how much will be spent on yet more imports from China, Mexico and Europe, is however, far from clear.

20 British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, when Mayor of London, exemplified this in his speech to the 2009 Conservative Party Conference, when he informed civic leaders of Manchester, Leeds and Newcastle that ‘if you want to stimulate [your cities] then you invest in London, because London is the motor not just of the south-east, not just of England, not just of Britain, but of the whole of the UK economy’ (https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2009/oct/06/michael-white-conservative-conference-diary). Now that he is prime minister, his tone has suddenly changed to one of investing in left-behind places outside London in order to level up the national economic geography, no doubt because of his desire to secure electoral support in those places.

21 When talk of ‘rebalancing’ the British economy began to gain traction following the Global Financial Crisis, policy and business leaders in London were quick to warn that ‘levelling up’ the country ‘could damage the capital’s status as a world-leading city’. This response not only seemed to subscribe to the misguided belief that pursuing a more equitable geographical distribution of economic success and prosperity would necessarily be at the expense of London, and national efficiency in general, but it also smacked precisely of the elitist detachment that has fuelled social and political discontent in the British regions (e.g., Financial Times, Citation2010).

22 This issue has come to the fore in the Covid pandemic, and how different national governments have territorially organized their economic lockdowns, distributed and administered social and economic support schemes, and worked with regional and local public health authorities to control the virus and deliver vaccine programmes.

23 Our academic journals have institutionalized this imperative, with their citation rankings and the narrow criteria used to judge the ‘worth’ and contribution of the articles they publish. Just to be clear, the problem is not one of pluralism of theories, concepts and methods in regional studies – there are strong arguments in support of pluralism (Martin, Citation2021); rather, the issue one of the purpose to which our theories and methods are put, and the normative and axiological principles that guide that purpose.

24 While the idea of ‘place-based’ policy has attracted increasing attention, there is a lack of clarity over just what, exactly, this means in practical terms and what are its contribution and limitations. To the extent that it refers to the importance of locally designed and locally implemented socio-economic policies that respond to the specific contexts, problems and potentialities of individual regions, cities or localities, then such policies may well have an important role to play in revitalizing ‘left behind’ places. But although such policies may be necessary, they are unlikely of themselves to be sufficient. Not only may they do little to change the larger macro-level processes, structures and policies that have produced ‘left behind’ places in their wake, local place-based policies may be constrained or even undermined in their impact by those very same macro-level forces. Place-based policies need to be supported by ‘place sensitive’ macro-economic policies and interventions, whereby the latter, where possible, are both examined for their likely, if unintended, spatially uneven impacts, and explicitly designed to prioritize the development needs and potential of lagging regions, cities and localities.

25 Something akin to a ‘Red Queen effect’ often operates, whereby ever more state spending (per capita) is necessary in global star cities in order just to maintain their growth rate and competitiveness.

REFERENCES

- Ascani, A., Faggian, A., & Montresor, S. (2020). The geography of COVID-19 and the structure of local economies: The case of Italy. Journal of Regional Science. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12510

- Atkinson, A. (2015). Inequality: What can be done? Harvard University Press.

- Atkinson, A., Hasell, J., Morelli, S., & Roser, M. (2017). The chartbook of economic inequality. https://www.charbookofeconomicinequality.com

- Autor, D. H., Dorn, D., & Hanson, G. H. (2013). The China syndrome: Local labor market effects of import competition in the United States. American Economic Review, 103(6), 2121–2168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

- Burawoy, M. (2005). For public sociology. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 4–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000102

- Burawoy, M. (2016). Sociology as a vocation. Contemporary Sociology: A Journal of Reviews, 45(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306116653958

- Burawoy, M. (2021). Public sociology. Polity.

- Coates, D. (2018). Flawed capitalism: The Anglo-American tradition and its resolution. Agenda.

- Coppola, G., Welch, D., & Querolo, N. (2020). Virus erupts in US cities where the poor have few defences. Bloomberg Prognosis, 28 March. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-28/virus-erupts-in-poor-u-s-cities-whose-people-have-few-defenses

- Davenport, A., Farquharson, C., Rasul, I., Sibieta, L., & Stoye, G. (2020). The geography of the COVID-19 crisis in England. Institute for Fiscal Studies, Briefing Note, 15 June, London.

- Donald, B., & Gray, M. (2019). The double crisis: In what sense a regional problem? Regional Studies, 53(2), 297–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1490014

- Financial Times. (2010). London’s leaders warn over push to narrow regional inequalities. Financial Times, 13 January. https://www.ft.com/content/ad1bc24e-339d-11ea-9703-eea0cae3f0de

- Gardner, J., Gray, M., & Moser, K. (2020). Debit and austerity: Implications of the financial crisis. Edward Elgar.

- Georgieva, K. (2020). A new Bretton woods moment, Speech, International Monetary Fund, Washington, 15 October 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/10/15/sp101520-a-new-bretton-woods-moment

- Gray, J. (1998). False Dawn: The delusions of global capitalism. Granta.

- Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018). The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- Hadjimichalis, C., & Hudson, R. (2014). Contemporary crisis across Europe and the crisis of regional development theories. Regional Studies, 48(1), 208–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.834044

- Hendrikson, C., & Muro, M. (2020). Will COVID-19 rebalance America’s uneven economic geography? Don’t bet on it, Brookings metro’s COVID-19 Analysis, Brookings Institution, Washington, April 2020.

- Hendrikson, C., Muro, M., & Galston, W. A. (2018). Countering the geography of discontent: Strategies for left-behind places. Brookings Institution.

- Hines, C. (2000). Localization: A global manifesto. Earthscan.

- Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

- Khan, Z., & McArthur, J. (2021). Let the transition begin. Op-Ed. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/let-the-great-transition-begin/

- Kose, M. A., Nagle, P., Ohnsorge, F., & Sugawara, N. (2020). Global waves of debt: Causes and consequences. World Bank Group.

- Krecké, E. (2020). Relevance beyond the crisis: The future of economics, Report, Geopolitical Intelligence Services. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/relevance-beyond-the-crisis-the-future-of-coronomics,economy,3164.html

- Lakner, C., & Milanovic, B. (2016). Global income distribution: From the fall of the Berlin wall to the great recession. The World Bank Economic Review, 30(2), 203–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/wber/lhv039

- Markusen, A. (1999). Fuzzy concepts, scanty evidence, policy distance: The case for rigour and policy relevance in critical regional studies. Regional Studies, 33(9), 869–884. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950075506

- Martin, R. L. (2008). National growth versus spatial equality? A cautionary note on the new ‘trade-off’ thinking in regional policy discourse. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 1(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1757-7802.2008.00003.x

- Martin, R. L. (2015). Rebalancing the spatial economy: The challenge for regional theory. Territory, Politics, Governance, 3(3), 235–272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1064825

- Martin, R. L. (2021). Putting the case for a pluralistic economic geography, (Impulses paper). Journal of Economic Geography, 21, 1–28.

- Martin, R. L., & Sunley, P. J. (1997). The post-Keynesian state and the space economy. In R. Lee, & J. Wills (Eds.), Geographies of economies (pp. 278–289). Arnold.

- Mazzucato, M. (2013). The entrepreneurial state: Debunking public vs private sector myths.

- Mazzucato, M. (2018). The value of everything: Making and taking in the global economy.

- Mazzucato, M. (2021). Mission economy: A moonshot guide to changing capitalism. Penguin.

- McFarlane, C. (2020). The urban poor have been hit hard by coronavirus. We must ask who cities are designed to serve. The Conversation, 3 June.

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2016). Starting at the source: Sustainability in supply chains. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/sustainability/our-insights/starting-at-the-source-sustainability-in-supply-chains

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2020). Risk, resilience and rebalancing in global value chains. XXX

- Moretti, E. (2012). The new geography of jobs. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Narotsky, S., & Besnier, N. (2014). Crisis, value, and hope: Rethinking the economy. Current Anthropology, 55(S9), S4–S16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/676327

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). Regional outlook: Productive regions for inclusive societies. OECD Publ.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2018). Productivity and jobs in a globalised world: (How) can all regions benefit? OECD Publ.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Beyond growth: Towards a new economic approach.

- Pettis, M. (2013). The great rebalancing: Trade, conflict and the perilous road ahead for the world economy. Princeton University Press.

- Piketty, T. (2015). The economics of inequality. Belknap.

- Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. Random House Business Books.

- Rochon, L.-P., & Rossi, S. (Eds.). (2017). A modern guide to rethinking economics. Edward Elgar.

- Rodriguez Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (And what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rodrik, D. (1998). Has globalization gone too far? Challenge, 41(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/05775132.1998.11472025

- Rodrik, D. (2018). Straight talk on trade: Ideas for a sane world economy. Princeton University Press.

- Rodrik, D., & Subramanian, A. (2009). Why did financial globalization disappoint? IMF Staff Papers, 56(1), 112–138. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/imfsp.2008.29

- Rose-Redwood, R., Kitchin, R., Apostolopoulou, E., Rickards, L., Blackman, T., Crampton, J., Rossi, U., & Buckley, M. (2020). Geographies of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620936050

- Rosés, J., & Wolf, N. (2020). Regional inequality in the long run: Europe 1900–2015. Mimeo, Department of Economic History, London School of Economics.

- Roy, A. (2020). The pandemic is a portal. Financial Times, April 3. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

- Rudiger, K. (2007). Offshoring, A threat for the UK’s knowledge jobs? The Work Foundation.

- Sandbu, M. (2020). The economics of belonging: A radical plan to win back the left behind and achieve prosperity for all. Princeton University Press.

- Scott, R. E., & Kimball, W. (2014). China trade, outsourcing and jobs, briefing paper 385. Economic Policy Institute.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2015). The great divide. Allen Lane.

- Storper, M. (2018). Separate worlds? Explaining the current wave of regional economic polarization. Journal of Economic Geography, 18(2), 247–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby011

- Streeck, W. (2016). How will capitalism end? Verso.

- Turner, A. (2012). Economics after the crisis: Objectives and means. MIT Press.