ABSTRACT

Taking a spatially sensitive approach to evaluating China’s quest of soft power, this paper conducted a media discourse analysis of European countries’ perceptions of China’s growing international influence in general, and its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in particular. Preliminary analysis reveals regional diversity in media coverage of the BRI that was partially caused by a country’s position as a ‘discourse leader’, ‘discourse responder’ or ‘discourse follower’. In terms of the contents, this paper noticed a huge discrepancy among the European countries towards the potential impacts of the BRI and China’s rise in international affairs, and recorded a shift from a rather positive to a cautious attitude among the European Union’s leaders. It is suggested that China’s spatially blind approach to using soft power to promote BRI in Europe may be partly to blame for its limited success so far.

BACKGROUND AND PROGRESS OF BRI IN EUROPE

Current geopolitical disruptions and rebalancing as exemplified by Brexit and an ‘America First’ doctrine have offered China the stage and opportunity to push for a new world order (Portland, Citation2017). Among the various slogans propagated, such as ‘the Chinese Dream’, the ‘Asia-Pacific dream’ and ‘a new type of major-country relationship’, many could agree that it is President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that draws the most ambitious map and offers the most expansive cooperative opportunities worldwide. Together with the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the BRI is building what Liu (Citation2015) termed ‘a new type of globalization’ – an ‘inclusive globalization’ (Liu & Dunford, Citation2016) led by China. First announced publicly in the autumn of 2013, there has been a growing volume of investment and infrastructure projects adding to the BRI list. Although Europe stands at the margin of China’s expansive BRI map, connections between China and European countries are strengthened by the New Silk Road economic corridor along its ancient route. In December 2014, for example, China agreed with Hungary, Serbia and Macedonia to build a rail link between Budapest and Belgrade, financed by Chinese companies. This rail line will then be connected to the Macedonian capital of Skopje and the Greek port city of Piraeus where COSCO, the Chinese shipping giant, operates two piers for container units. While projects such as this strengthen cross-border transport connections between Central and Southeastern Europe, Chen et al. (Citation2019) see the BRI as an epochal initiative that affects three linked master process: globalization, urbanization and development. Its motivating conditions are deeply embedded in China’s domestic regional spaces.

Infrastructure is a major avenue for China to forge direct physical connections to Europe. The most important connection thus far is the Trans-Eurasia railroad from the city of Chongqing in south-western China to Duisburg, Germany, launched in 2011. It is perhaps not surprising to see China set its railroad end in the landlocked regions, given labour and land costs in coastal cities are going up, and Beijing has been pushing and inducing foreign investors and domestic producers to move inland through its ‘Go West’ policy. Interior megacities such as Chongqing, Chengdu, Xi’an and Kunming have been booming as major destinations for large new manufacturing projects. By 2018 China has already sent a total of 10,000 trains, carrying 35 million RMB-worth of goods to Europe (Wang, Citation2018). Besides rail connections, China has also launched an infrastructure build-up within Europe. These include a new bridge across the Danube River inaugurated between China and Serbia; the Stanari Thermal Power Plant in Bosnia (up to US$ 1.7 billion); and the Bar–Boljare motorway in Montenegro (US$984 million) (The China Daily, Citation2014). Infrastructure projects of such scale have been very rare in these countries for more than 20 years (Chen & Mardeusz, Citation2015). China’s major outreaching efforts hence open up a new era of China’s presence and influence. The sum of Chinese direct investment in Europe peaked at €37.5 billion in 2016, covering wide sectors of energy, automotive, agriculture, real estate, industrial equipment, and information and communications technology (Corre, Citation2018). Besides the state and state-owned enterprises, other private firms are also tapping into this huge market opportunity. Huawei, for example, is building a great deal of national telecoms networks and has been proactively marketing its telecommunications networks internationally under the ‘digital BRI’ banner (Devonshire-Ellis, Citation2019).

Many see this increasing outward investment from China and Chinese companies as implying a reversal of power between the Western empires and China. Such a linear perspective of China’s rise to power as a succession to the old circle of influencers and as a challenge to established world orders dominates the current geopolitical literature (Agnew, Citation2010). China’s quest for soft power to build alliances in general and to promote BRI in particular has been tempered by caution, critique (Holslag, Citation2017) and the belief that it is a ‘mission impossible’. Yet such generalized conclusions regarding China’s soft power deficit opposes this country against the established power structure as if it is a unified whole. This paper introduces a more spatially sensitive approach to study the soft power of China through the lens of global media discourse on the BRI. It focuses on Europe as an old and internally differentiated powerhouse and explores how individual European countries have been responding to China’s soft power appeal, and what factors have shaped the tones and directions of discourse surrounding the BRI in this region.

GEOPOLITICS AND SOFT POWER

In the tradition of (neo-)realist analysis of international relations, material resources and spatial factors have traditionally been treated as central to geopolitics (Lonsdale, Citation1999). The process of globalization however has fundamentally shifted the paradigm from ‘the modern world of geopolitics and power to the postmodern world of images and influence’ (Ham, Citation2001, p. 4). The power of attraction, or ‘soft power’, is argued to outweigh coercion and is seen as the key asset in global competition (Marklund, Citation2015). The application of soft power occurs when ‘one country gets other countries to want what it wants … in contrast with the hard or command power of ordering others to do what it wants’ (Nye, Citation1990, p. 166, original emphasis). In contrast to ‘hard power’, which refers to the ability to coerce others through a country’s military or economic muscle, influences of soft power are grounded upon the attractiveness of a country’s culture, political ideals, and policies (Nye, Citation2004). Discourses in shaping and broadcasting one’s cultural appeal, economic superiority and political quality are some of the crucial inputs in constructing and strengthening ones’ soft power, as seen in the rising attractions of South Korea (Valieva, Citation2018), Singapore (Chong, Citation2009) and other middle and rising powers on the world stage. Moreover, the power of attraction is no longer reserved for the nation-state but can be exerted by non-state organizations, multinational enterprises, cities, regions and their alliances (Khatib & Dodds, Citation2009).

Modern China’s rise outside the global circle of powers is a recent phenomenon, hence ‘China in itself will have to become a much more important focus of study than it has been for critical geopolitics in particular and for political geography more generally’ (Agnew, Citation2010, p. 580). China’s international diplomacy has for a long time been secondary to its economic development goals. Opening-up reform nonetheless has exposed its socio-economic development to the world politics. The global communication research in the 1990s therefore was dominated by topics relate to the patterns and effects of transnational media expansion into China (Zhao, Citation2013). Zhao (Citation2009) nonetheless noticed that the concept of ‘soft power’ has gained popularity among the Chinese elites since 2001 along with its media industry’s ‘going global’ initiative. In 2011, the Sixth Plenary Session of 17th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party published a high-profit decision on cultural system reform in order to strength its cultural soft power (The State Council, Citation2011), and President Xi Jinping has since reiterated the importance of soft power in various occasions, explicitly emphasizing the needs to improve the appeal and credibility of international discourses of China through new media, and to better communicate China’s messages to the world (Xinhua News, Citation2015). Yet to Zhao (Citation2009, p. 247), ‘China’s current approach to soft power lacks a contemporary moral appeal and therefore is hardly sustainable in the competition with the United States to inspire the vision of building a free and prosperous world.’ In the same vein, Sun (Citation2010) pointed out that China has failed to articulate a value that the rest of the world aspires to and a ‘charm offensive’ is how Western commentators perceive China’s engaging with the world (Kurlantzick, Citation2007). Nye (Citation2015, Citation2012) hence concluded that China still faces a ‘soft power deficit’. The US–China trading war since 2018 once again underlines the limited success China has achieved so far in reversing a net negative opinion about its global influence (Hammond, Citation2018). The recent pandemic, Hong Kong riots and China–Australia trading conflicts have done nothing to improve its image among Western audiences, especially when this news is broadcast globally by Western monopolized media channels (Shambaugh, Citation2015).

Yet these rather negative views on China’s pursuit of soft power have been reached in largely aspatial or under-spatialized terms. Much attention vis-à-vis geopolitics and soft power tends to focus on relations between China and the West as a whole, and the United States in particular. Most of the literature takes a linear view of power concession in which China is just another great power rising to the top of the world hierarchy (Agnew, Citation2010). This positions China to the opposite of the established world order and politics as a whole. But as will be seen later, such conceptualization diverts attention from the flux and complex nature of global spatiality and how China tailors (or not) its soft power strategy on an intra-regional basis.

One of the most intriguing cases in this respect is China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The Soft Power 30 report highlighted that ‘what sets the One Belt, One Road initiative apart is that, for perhaps the first time in the contemporary era, China has managed to combine the hard power of its economic muscle with the soft power of a cooperative, inclusive narrative that emphasizes shared prosperity and regional development’ (Portland, Citation2017, p. 18). Yet questions remain regarding how different regions respond to this ‘emergent geo-political economic culture’ (Liu et al., Citation2021). For Shambaugh (Citation2015), ‘money’ has been the strongest instrument used by Beijing to appeal its potential partners, whereas Putten et al. (Citation2016) believed that China’s official approach to promote BRI is a matter of public diplomacy, a narrative formation around the ‘inclusive’, ‘transformative’ and ‘complementary’ benefits across Eurasia and Africa. A thorough analysis of the world’s view on the BRI of course goes beyond the scope of a single paper. The rest of this paper therefore will focus on Europe and explores how BRI is discussed there in an attempt to evaluate China’s soft power.

DISCOURSE ANALYSIS

Discourse analysis is a broad term for the study of the ways in which language is used between people, both in written texts and spoken contexts. Conceptualization and development of this methodological approach is strongly impacted by fundamental epistemological and ontological progress in social science (Keller et al., Citation2018). There is a general consensus regarding the socially mediated nature of knowledge construction, yet two sub-branches in decomposing knowledge and its associated discourses could be distilled (Keller, Citation2011). The first one, led by scholars such as Berger and Luckmann (Citation1966), primarily focuses on the constitution and stabilization of knowledge on the micro-level of interactions among the ordinary members of society. The use of language, or discourse, helps to typify a shared social reality, which is then legitimized by various forms and social organizations. Discourse analysis could help to unveil these institutional structures that fix or transform the shared social order. The other approach, in comparison, concentrates on the macro institutional contexts of the production and integration of knowledge. In The Archaeology of Knowledge, Foucault (Citation1972 [1969]) broadened discourse analysis beyond formal linguistic aspects. He believed that discourses represent ‘systems of thoughts’, that is, they are institutionalized patterns of knowledge that become manifest in disciplinary structures and operate by the connection of knowledge and power. Therefore, discourse analysis needs to take into account the context, the social and cultural framework of the conversation besides what is said (Johnstone & Eisenhart, Citation2008).

So far these two approaches have been largely developed in parallel to each other, but a more holistic way of conceptualization is desired in gaining deeper understanding of our complex and multifaced society. The approach taken in this paper follows that of Keller (Citation2011) by adopting a ‘sociology of knowledge approach to discourse’ (SKAD). The strength of SKAD lies in its eclectic perspective which views our sense of everyday reality and thus the meaning of everyday objects, conversations and events as the outcome of a permanent, routinized interaction. By combining the macrolevel theorization of discourse with the microlevel conceptualization of everyday knowledge, SKAD is able to investigate the social construction of ‘soft power’ on multiple levels (Cheng, Citation2009). Such comprehension of analysis could be operationalized through three levels (Nielson & Nørreklit, Citation2009, p. 205), including:

The qualities of the text itself, which concentrates on ‘what is said’ by analysing the vocabulary, the use of metaphor and rhetorical elements, the argument types and the relationship between sentences.

The discourse practice, that is, rather than a micro-analysis of linguistic or rhetorical features, this step focuses on whether and to what extend the textual products re-produce and represent existing discourse.

The wider social and institutional contexts that serve as the paradigmatic framework in which the discourse takes place.

Establishing the context: through the Google search engine, I first assembled a European database of media articles commentating on the BRI between 2008 and 2018. This stage took full advantage of the ‘advanced search’ Google function to define regions and languages. For the scope of this paper, I have focused on eight countries, representing Western, Eastern, Southern Europe and Scandinavian countries. Following Baroutsis and Lingard (Citation2017), the number of articles and changes per year were used to indicate the discourse position of focused countries (see the next section for details). Although I have taken into account the different languages used in domestic media broadcasts, it is admitted that Google search might not be able to provide a full coverage of discourse published in other languages other than English. Therefore, results need to be read with caution.

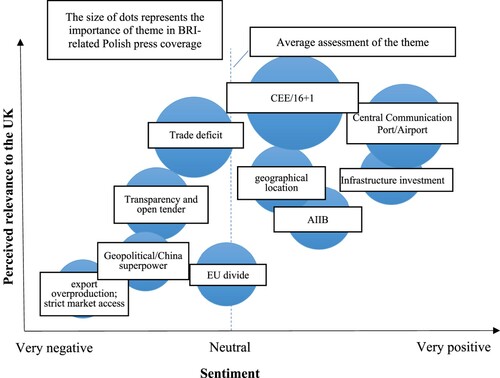

The qualities of the text: detailed analysis of all media coverage in these European countries is not possible in one paper. Therefore, this step concentrated on the BRI’s media exposure in Poland and the UK as representatives of countries that directly participated in BRI and those who are marginally involved. For each county, the texts of the top 50 most relevant articles listed on Google were selected and analysed. For each article, the key ‘themes’ of discourse were identified first (such as ‘AIIB’, ‘transparency’), and the frequencies of their mentioning were used as indication of relevancy to a particular country.

The discourse practice: concentrating on these ‘themes’ identified above, this step tried to interpret the intentions, sentiment and types of argument through examining the subjective and commentary vocabularies, metaphors, and structure of paragraphs as suggested by Johnstone (Citation2018). I ranked the sentiment of each theme from very negative (if strong words such as ‘threat’ and ‘challenge’ were used), somewhat negative (if words such as ‘caution’ were used), somewhat positive (if the theme was discussed in balance with more positive tunes), to very positive (if there were no negative comments). To control bias, these codings were tested and revised after discussing with experts from China, Europe, the United States and Australia during a BRI forum organized in China at the end of 2018 and in a special conference session on the BRI in the UK early 2019. Findings are presented below.

GLOBAL NARRATIVES OF THE BRI

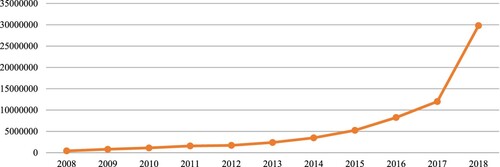

shows the total Google search returns with the keywords ‘belt and road’. It illustrates a clear rise in attention from the international media and the following three phases could be distilled:

2008–13: Preparation.

2013–16: Announcement and initial reactions, when Chinese regional governments, state-owned and private enterprises increasingly compete for opportunities to launch BRI projects with European partners (Shepard, Citation2016).

2016–present: taking-off and wider diffusion. Partnership becomes more targeted.

It is expected that in the next decade (2020–30, limiting the take-off stage to be very short), there might be a stabilization phrase when BRI is gradually being implemented. For example, in her speech delivered in the 2019 BRI Forum, Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), described this implementation phrase as ‘BRI 2.0’ which includes further promotion of trade, financial inclusion and people-to-people connections (IMF, Citation2019). It is also expected that the discourses on the BRI will become more focused and concrete in the following decades (2030 onwards), when completed projects start operating and risk management becomes prominent.

At the beginning and overall, the announcement of the BRI has been welcomed by a large number of countries. But its global propaganda has invited caution and criticism, especially at the country level (Herrero & Xu, Citation2019). This is perhaps not surprising given the time needed to evaluate the possible effects of participating in the BRI by individual countries. Some of the infrastructure and policy reforms envisaged by the BRI will be difficult to implement, creating risks ranging from fiscal sustainability, to negative environmental and social implications. Moreover, opportunities for growth will likely be contingent upon appropriate macroeconomic conditions and supportive institutions, which in turn will differ for different countries and different social groups within countries (Chen et al., Citation2019).

The global discourses on the BRI are still primarily shaped by a few superpowers, many are rather negative on the greater penetration of China at the national level. Among the champions are the United States, India, Australia and Japan, who were discussing a joint regional infrastructure scheme as a countermeasure of Beijing’s spreading influence. The United States has long been the dominant economic and institutional leader in the world and holds massive interests in Asia and Asia-Pacific regions. Viewing China as its ‘strategic competitor’, it has been very proactive in building alliances through, for example, the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy (Cho, Citation2019). India, on the other hand, is a fast-rising economy that tends to view itself on a par with China at least in Asia. The proposed China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, for example, has raised serious concerns among Indian political leaders about establishing an empire of ‘exclusive economic enclaves’ (Malik, Citation2018, p. 67). Australia and Japan, the long-time allies of the United States, and counter powers to China in Southeast and East Asia, also perceive the BRI as a big threat to their respective regional influence. Japan’s former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, for example, pledged to provide around US$110 billion for ‘quality’ infrastructure projects in Asia, demonstrating his own version of ‘checkbook diplomacy’ (Deutsche Welle, Citation2017).

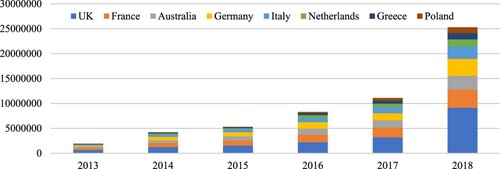

The situation in Europe is different. Unlike other major economic blocks, there is no absolute superpower in this region so that China’s extension is more of a case-by-case negotiation (Putten et al., Citation2016). When combining ‘Belt and Road’ with individual European countries as key words in the search, I noticed that the bigger economic entities in Europe, including the UK, France and Germany, have been the leading countries commenting on China’s BRI (). Yet it is worth pointing out that, in 2019, Italy signed a Memorandum of Understanding to officially become a member of the BRI, which has raised eyebrows from the main EU countries (BBC, Citation2019). Italy may be among the group of leaders or stand in a category by itself, with the media coverage still catching up on its official participation.

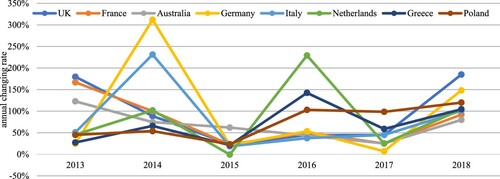

breaks down the annual changing rates of media coverages. Several patterns are worth noting. First of all, UK and France were the two countries with the quickest reaction to the announcement of the BRI. This implies their leadership in Europe and globally with respect to China relations. Here I classify them as ‘discourse leaders’ to distinguish them from the ‘responders’ and ‘followers’ (see below). Their different role in setting the tune and directions of media discourse reflects some of the regional diversity and offers a potential reason why China’s soft power penetration has achieved different effects. The Chinese government was mainly interested in cooperating with these ‘old’ economic powerhouses on the BRI projects in ‘third countries’, such as cooperating with France in francophone Africa. It is also noticed that the volume of discourse led by the UK and France has later increased slower except when concrete cooperation happened. Again, this reflects their wider scope of diplomatic attention and balancing acts. The UK’s Brexit vote and the following negotiation with the EU have borne higher weight than BRI. In France, the initiative had initially raised curiosity among policymakers and business communities for its potential benefits. But the number of projects launched under this framework remains limited, although in Xi’s latest visit in March 2019, 15 business deals totalling about €40 billion were signed (Pennetier & Irish, Citation2019). The Chinese government has also invested comparatively less in promoting BRI in France than it did in the Mediterranean and Central and Eastern European countries.

Second, Germany attended to the BRI noticeably in 2014 and 2018. Italy increased its media exposure of the BRI in 2014 and the Netherlands in 2016. These countries could be termed as ‘discourse responders’, that is, discourses are triggered when direct encounter with BRI happens or is on the horizon. For example, in the Netherlands, the Port of Rotterdam Authority organized two seminars in 2016 to discuss a potential rail connection with China (Port of Rotterdam, Citation2016), which produced surges in media reports. Since their engagements with the BRI are much more tangible compared with those in the UK and France, China has been putting more effort to engage with these ‘emerging leaders’, who might head the EU’s interaction and engagement with the BRI in the future.

Third, for economically less strong states such as Greece and Poland, they only started to connect with the BRI after 2016 when concrete effects took shape and more evidence was available. They could therefore be termed as ‘discourse followers’. Nonetheless, Greece, with the further growth of its Piraeus port, is catching up with the BRI quickly. Poland, with a couple of its border cities near Belarus, is strategically located for the main China–Europe Freight Train route. Both countries may be more important for and involved with the BRI than the media coverage noticed here. summarizes the diverse engagement routes of European countries with the BRI.

Table 1. Types of engagement with the BRI in selected European countries.

Besides this quantitative change, media research into the discourse contexts indicates a subtle rhetoric transformation as well. Immediately after the announcement of the BRI, discourses in Europe were filled with expectations and interests to get involved. Later the tones changed to a ‘wait and see’ attitude, and the EU leading countries became more conservative. This transformation was caused in particular by the fuzzy concept of the BRI; the failed delivery of new investments by the Chinese side; and the drained promotion effort of China in Western Europe (Arduino, Citation2016). Since 2018, there has been a strong push towards a conjoined EU narrative on the BRI. A briefing published by the European Parliament in July 2016, for example, emphasized that the BRI has to be coordinated with the EU under mutually agreed ‘rules of the game’. It urged all EU member states to come up with a common position as a warning against potential exploitation by China in a ‘divide and rule tactic’ within Europe (Grieger, Citation2016).

Several reasons have potentially caused this change, including (1) growing impatience and dissatisfaction with what was agreed and what was delivered; (2) Chinese offers of funding often fail to comply with EU regulations on tenders and state aid; (3) increasingly suspicious voices from global media and academic reports; (4) lack of concrete, materialized evidence to show the added value of the BRI; and (5) other major domestic and international challenges such as Brexit; changing US diplomacy and the current pandemic.

To complement the above macrolevel analysis, the following analysis zooms in on the UK and Poland to uncover detailed patterns and underlining reasons for discourse leaders and followers. These two countries are representative of mature and emerging economies in Europe. Moreover, while Poland has established concrete investment deals with China, the UK so far still positions itself at the margin of the BRI.

DISCOURSE LEADERS AND FOLLOWERS

Discourse in the UK

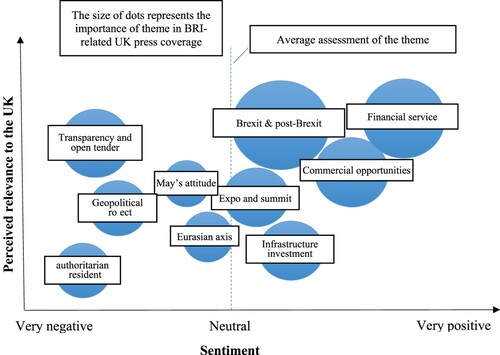

As summarized in , the dominant reason for the UK to get engaged was for the vast business opportunities envisaged with the BRI, especially for its financial services sectors. This topic has been discussed as most relevant to the UK and generally in positive tones based on context analysis (). Collaborations with China have been led by key institutions including the HM Treasury and the Foreign & Commonwealth Office (Summers, Citation2016). The visit of then Chancellor of HM Treasury George Osborne to Xinjiang in the north-west of China in September 2015, and the reciprocal visit of President Xi to the UK in October 2015, symbolically launched the Sino-UK collaboration (UK Government, Citation2015a). Building on previous collaborative work, agenda of Sino-UK collaboration has been primarily focused on building an ‘infrastructure alliance’ in the third markets, including Asia, Africa and Latin America. It is expected that the UK’s financial management sector could benefit substantially if the BRI’s ambition of leveraging greater use of renminbi for investment and trade outside China is realized (UK Government, Citation2016a).

A proactive communicator of the BRI inside the UK is the China–Britain Business Council (CBBC). In 2015, the CBBC published the first comprehensive report on ‘One Belt, One Road’ in partnership with the Foreign & Commonwealth Office. It offered a systematic review of the 13 major regions and seven key sectors on which the BRI was going to focus. These sectorial opportunities were identified in infrastructure, financial and professional services, agriculture and the environment, advanced manufacturing and transport, energy and resources, and e-commerce and logistics, with secondary opportunities in healthcare and life sciences, tourism, and creative and cultural industries (CBBC, Citation2015). The second report outlined a number of commercial ‘case studies’ of cooperation relating to the BRI. However, Summers (Citation2016) pointed out the considerable variation in the extent to which these cases were linked to the BRI, with some even predating the initiative, hence indicating a repackaging of projects under the BRI to appeal to wider interests. The CBBC’s third report focused on the BRI’s three southern economic corridors and maritime routes. This report was prepared to coincide with the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in May 2017. The CBBC also organized follow-up BRI events, seminars, business-to-business roundtables and closed-door stakeholder discussions between UK and Chinese stakeholders. Its latest report, published in 2019, aimed to promote UK expertise to the Chinese government and business stakeholders working in unfamiliar and challenging third countries.

Yet given the global influence of the UK, the BRI may be more suitably viewed as one part of the evolving Sino-UK ties, although the UK joining AIIB bears symbolic importance to China. Summers (Citation2016), for example, noted that the BRI has since not been accorded a particularly high importance by Chinese officials in their dealings with the UK. For example, During Xi’s state visit to the UK in October 2015, the BRI was mentioned once in the joint statement as a ‘major initiative’, along with the UK’s initiative in the Northern Powerhouse (UK Government, Citation2015b). Later in the 12th UK–China Joint Economic and Trade Commission meeting, the BRI again featured once in building an ‘infrastructure alliance and collaboration in third markets’ (UK Government, Citation2016b), suggesting that it only forms one part of a broad trade and investment relationship between the two. From the UK’s perspective, planning for Brexit and sustaining the country’s economic stability and further growth have been the top concern for Theresa May and Boris Johnson – although the BRI has been discussed in this context as a potential benefit to the UK. May’s office had initially taken a more cautious approach, highlighting the transparency issue of the BRI under an authoritarian president (Parker, Citation2018). The Johnson government nonetheless has made public its enthusiasm of the BRI and is supportive of Chinese investment (Lu, Citation2019).

Discourses in Poland

Given the strategic importance of Poland in terms of concert projects and its higher tolerance of China’s socialism system, Beijing has put the BRI on the agenda of various levels of bilateral meetings and dialogues with Poland. These included, for example, a seminar on ‘China–Poland Investment Cooperation within the Belt and Road Initiative’ held in Beijing in April 2016, and a huge international Silk Road Forum in Warsaw in June 2016 that was attended by Xi and Polish President Andrzej Duda. Chinese delegates, including representatives of state agencies, local governments and businessmen, were sent to promote the Silk Road and inspect the investment environment in Poland. Szczudlik (Citation2016) noticed that in seeking collaboration with Poland, the Chinese partners had become more and more proactive. This was evidenced by the fact that instead of asking the Polish side for investment suggestions, recent Chinese visits often brought with them more detailed project proposals under the BRI framework.

Overall, both the political and business circles in Poland held a positive perception of the BRI. Most of them associated BRI with more opportunities than threats, which has not changed under Poland’s new leadership after the 2015 elections. Narratively, it seems that the new Polish government was even more eager to encourage Chinese businesses to invest in Poland through, for example, special economic and industrial zones, and to expand Polish exports to China using existing and new inland (cargo trains) and maritime (between Shanghai, Tianjin and the Polish port of Gdansk) connections. The strategic location of Poland for the BRI and its membership in Central–East Europe (CEE) 16+1 were other themes frequently discussed in the media as relevant and positive to Poland. There were noticeable win–win opportunities between the two sides, given the ambitious plan of the current Polish government for reindustrialization and improving transport infrastructure, including highways such as that linking Finland, the Baltic States, Poland and Germany; and another via Capratia, linking Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania and Greece. There was also a plan to build a central international airport between Lodz and Warsaw, all of which need substantial capital investment. Poland’s membership in AIIB was often highlighted as a potential lever to meet such capital needs ().

Recently, some more negative voices were emerging that enumerated the potential economic threats of the BRI, such as the exports of subsided Chinese overproduction, and the danger of an increasing trade deficit on the Polish side (regarded as highly relevant to Poland). Moreover, a recent visit by the Chairwomen of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the Chinese Parliament, Fu Ying, was perceived as stimulating rivalry between EU states, as she was reported to urge Central European countries to loosen administrative barriers for BRI projects and said that the first country to deal with this problem had a greater potential to become the Silk Road logistical hub (Szczudlik, Citation2016). Beyond Poland, China’s greater penetration in CEE has also triggered anxiety among the ‘old’ EU leaders such as Germany and France. For them, these less developed CEE member states were the ‘blind spot’ of the EU. Through CEE, Beijing’s primary intention was to access the European market, gain access to relatively cheap and qualified labour, and gradually destabilize the EU from within (Holslag, Citation2017). The China-inaugurated 16+1 platform in 2012 with 16 CEE countries (both EU and non-EU), for example, has often been criticized as a facade project for countries in the region, as all 16 CEE countries had seen growing trade deficits with China. Poland was often mentioned in these discourses as an example of potential EU divide under the growing Chinese geopolitical pressure (Szczudlik, Citation2016).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

Taking a geographically sensitive perspective, this paper explores China’s pursuit of soft power in promoting its BRI. Media discourses in representative European countries were studied and the result shows China has still not managed to deliver a clear and convincing message to EU leaders in its marketing effort.

Generally, there were growing frustration and cautions in European discourses regarding the graduate rolling out of the BRI. Following the dominantly negative view led by the United States and Australia, many European countries, especially the ‘discourse leaders’, started to view the BRI as a symbol of China’s growing influence in international affairs, especially in some of the backwaters in Europe. As a result, there is now a strong call for a coordinated response from the EU to countermarch China’s influence, a response that is centred on its principles, norms and rules (European Commission, Citation2018). Therefore, it seems that China has not been very effective in pushing BRI through its soft power, or at best, its success is imbalanced geographically. Yet unlike the previous literature, which tends to attribute China’s limited success in pursuing soft power to Western ideological resistance (Zhao, Citation2013), this paper unveils a deeper reason, that is, China’s somewhat spatially blind and pragmatic strategy in marketing the BRI. As shown in the preceding discussion, the larger EU member states are the leaders in forming and shaping a pan-Europe view on the BRI. Yet after a first wave of diplomatic engagement, the Chinese government was perceived to turn passive in promoting the BRI in Western Europe, leading many in the latter to regard the BRI as having a ‘minor’ or ‘moderate’ relevance (Putten et al., Citation2016). In comparison, Beijing has been very proactive in approaching the CEE and Mediterranean countries. While this ‘pick and choose’ strategy (Godement & Vasselier, Citation2017) has boosted its popularity in these countries, as shown in the case of Poland, it has nonetheless raised serious concerns at the EU level regarding China’s threat in complicating EU diplomacy and undermining its standard-setting power. Moreover, there has been a lack of feedback loop in accessing the diverse perceptiveness of the BRI. So far, the Chinese diplomatic efforts were made one way to decision-makers in political and business circles, sometimes even behind closed doors. In doing so, China has stirred hot debates in policy-making circles about its motivations and the potential risks for EU states and business. Yet there is a lack of dedicated institutions in China that collect and synthesize these spatially different discourses and adjust China’s promotion strategy accordingly. Therefore, there seems to be a long way to go before China masters a spatially ‘smart’ soft power strategy.

Theoretically, this paper challenges a spatially blind approach in assessing China’s soft power pursuit and contributes to the study of geopolitics rebalancing through the world media discourse. Constrained by space, this paper was not able to investigate and compare the changing discourse on China’s rise between the old power circles of the United States and Europe and within a particular country in great depth. How non-state actors influence the media discourses and shape the nation-state’s engagement with China is another worthwhile topic to study. Moreover, it will be interesting to estimate the cause and effect of concrete BRI investment in each region and the direction of media discourse if accurate data become available.Footnote1 Last but not least, how the current pandemic has influenced the soft power of China and how BRI might be used to ease the damages caused by COVID-19 are also timely topics worth exploring further.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 A potential data source is the China Global Investment Tracker (https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/), which publishes the value of China’s overseas investment and construction since 2005. Chen and Lin (Citation2018) provide an initial attempt to access the economic impact of the BRI at a regional level.

REFERENCES

- Agnew, J. (2010). Emerging China and critical geopolitics: Between world politics and Chinese particularity. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 51(5), 569–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2747/1539-7216.51.5.569

- Arduino, A. (2016). China’s One Belt One Road: Has the European Union missed the train? Nanyang Technological University.

- Baroutsis, A., & Lingard, B. (2017). Counting and comparing school performance: An analysis of media coverage of PISA in Australia, 2000–2014. Journal of Education Policy, 32(4), 432–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1252856

- BBC. (2019). Italy joins China’s New Silk Road project. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-47679760.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. Penguin.

- CBBC. (2015). One Belt One road. China–Britain Business Council. http://www.cbbc.org/resources/one-belt-one-road/.

- Chen, M. X., & Lin, C. (2018). Foreign investment across the Belt and Road: Patterns, determinants and effects. World Bank Group.

- Chen, X., & Mardeusz, J. (2015). China and Europe: reconnecting across a New silk road. The European Financial Review. https://www.europeanfinancialreview.com/china-and-europe-reconnecting-across-a-new-silk-road/.

- Chen, X., Miao, J. T., & Li, X. (2019). China-led globalization? Understanding and making policy for risk in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Regions Magazine, 287(1), https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13673882.2012.10554270

- Cheng, A. Y. N. (2009). Analysing complex policy change in Hong Kong: What role for critical discourse analysis? International Journal of Education Management, 23(4), 360–366. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513540910957453

- The China Daily. (2014). Li forges new link in Serbian relations. December 19, 2014, p. 1.

- Cho, I. H. (2019). Dueling hegemony: China’s Belt and Road Initiative and America’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific strategy. The Air Force Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 2(4), 14–29.

- Chong, A. (2009). Singapore and the soft power experience. In A. F. Cooper, & T. M. Shaw (Eds.), The diplomacies of small states (pp. 65–80). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Corre, P. L. (2018). Chinese investments in European countries: Experiences and lessons for the ‘Belt and road‘ initiative. In M. Mayer (Ed.), Rethinking the Silk Road (pp. 161–175). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Deutsche Welle. (2017). China’s ‘New Silk Road’ – Perception and reality. https://www.dw.com/en/chinas-new-silk-road-perception-and-reality/a-38818750

- Devonshire-Ellis, C. (2019). The US, Huawei and the Belt & Road’s new 5G supply chains. Silk Road Briefing. https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2019/05/21/us-huawei-belt-roads-new-5g-supply-chains/

- European Commission. (2018). Joint communication on connecting Europe and Asia. https://eeas.europa.eu/sites/eeas/files/joint_communication_-_connecting_europe_and_asia_-_building_blocks_for_an_eu_strategy_2018-09-19.pdf

- Foucault, M. (1972 [1969]). The archaeology of knowledge. Routledge.

- Gaspers, J. (2016). Germany and the ‘Belt and Road’ initiative: Tackling geopolitical implications through multilateral frameworks. In F.-P. van der Putten (Ed.), Europe and China’s New Silk Roads (pp. 24–30). ETNC.

- Godement, F., & Vasselier, A. (2017). China at the gates: A new power audit of EU–China relations. The European Council on Foreign Relations.

- Grieger, G. (2016). One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s regional integration initiative. European Parliament.

- Ham, P. V. (2001). The rise of the brand state: The postmodern politics of image and reputation. Foreign Affairs, 80(5), 2–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/20050245

- Hammond, A. (2018). Beijing and its soft power deficit. ARAB News. https://www.arabnews.com/node/1275141

- Herrero, A. G., & Xu, J. (2019). Countries’ perceptions of China’s Belt and Road Initiative: A big data analysis. Bruegel Working Paper, Issue 01.

- HKTDC. (2020). The Belt and Road initiative. Hong Kong Trade Development Council. https://research.hktdc.com/en/article/MzYzMDAyOTg5.

- Holslag, J. (2017). How China’s New Silk Road threatens European trade. The International Spectator, 52(1), 46–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2017.1261517

- IMF. (2019). BRI 2.0: Stronger frameworks in the New phase of Belt and road. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2019/04/25/sp042619-stronger-frameworks-in-the-new-phase-of-belt-and-road

- Johnstone, B. (2018). Discourse analysis. Wiley & Sons.

- Johnstone, B., & Eisenhart, C. (eds.). (2008). Rhetoric in detail: Discourse analyses of rhetorical talk and text. John Benjamins.

- Keller, R. (2011). The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse. Human Studies, 34(1), 43–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10746-011-9175-z

- Keller, R., Hornidge, A.-K., & Schünemann, W. J. (eds.). (2018). The sociology of knowledge approach to discourse. Routledge.

- Khatib, L., & Dodds, K. (2009). Geopolitics, public diplomacy and soft power. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, 2(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/187398609X430589

- Kurlantzick, J. (2007). Charm offensive: How China’s soft power Is transforming the world. Yale University Press.

- Liu, W. (2015). Scientific understanding of the Belt and Road Initiative of China and related research themes (in Chinese). Progress in Geography, 35(5), 538–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.11820/dlkxjz.2015.05.001

- Liu, W., & Dunford, M. (2016). Inclusive globalization: Unpacking China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Area Development and Policy, 1(3), 323–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23792949.2016.1232598

- Liu, Z., Dunford, M., & Liu, W. (2021). Coupling national geo-political economic strategies and the Belt and Road Initiative: The China–Belarus Great Stone Industrial Park. Political Geography, 84. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2020.102296.

- Lonsdale, D. J. (1999). Information power: Strategy, geopolitics, and the fifth dimension. Journal of Strategic Studies, 22(2–3), 137–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01402399908437758

- Lu, Z. (2019). ‘Pro-China’ Boris Johnson ‘enthusiastic’ about Belt and Road plan. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3019884/pro-china-boris-johnson-enthusiastic-about-belt-and-road-plan?onboard=true.

- Malik, M. (2018). China and India: Maritime maneuvers and geopolitical shifts in the Indo-Pacific. Rising Powers Quarterly, 3(2), 67–81.

- Marklund, C. (2015). The return of Geopolitics in the Era of soft power: Rereading Rudolf Kjellén on geopolitical imaginary and competitive identity. Geopolitics, 20(2), 248–266. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.928697

- Nielson, A. E., & Nørreklit, H. (2009). A discourse analysis of the disciplinary power of management coaching. Society and Business Review, 4(3), 202–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/17465680910994209

- Nye Jr., J. S. (1990). Soft power. Foreign Policy, 80(Autumn), 153–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1148580

- Nye, J. S. (2004). Soft power: The means to success in world politics. PublicAffairs.

- Nye Jr., J. S. (2012). China’s Soft Power deficit. Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304451104577389923098678842. Published May 8, 2012.

- Nye Jr., J. S. (2015), The Limits of Chinese Soft Power. Project Syndicate. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-civil-society-nationalism-soft-power-by-joseph-s--nye-2015-07?barrier=accesspaylog

- Parker, G. (2018). Theresa May declines to endorse China’s Belt and Road initiative. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/6e39fd0e-0517-11e8-9650-9c0ad2d7c5b5

- Pennetier, M., & Irish, J. (2019). France seals multi-billion dollar deals with China, but questions Belt and Road project. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-france-china-idUSKCN1R61NF.

- Port of Rotterdam. (2016). One Belt One Road. https://www.portofrotterdam.com/en/doing-business/logistics/connections/one-belt-one-road

- Portland (2017), The soft power 30. USC Center on Public Diplomacy. https://softpower30.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/The_Soft_Power_30_Report_2017-1.pdf

- Putten, F.-P. v. d., Frans Paul van der Putten, John Seaman, Mikko Huotari, Alice Ekman, & Miguel Otero-Iglesias. (2016). Europe and China’s New Silk Roads. A Report by the European Think-Tank Network on China (ETNC).

- Shambaugh, D. (2015). China’s soft-power push: The search for respect. Foreign Affairs, 94(4), 99–107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24483821

- Shepard, W. (2016). Why the China–Europe ‘Silk Road’ rail network is growing fast. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2016/01/28/why-china-europe-silk-road-rail-transport-is-growing-fast/#28b2ea54659a

- The State Council, China. (2011). Communique of the Sixth Plenary Session of the seventeenth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Xinhua News. https://www.donews.com/dzh/201110/660225.shtm

- Summers, T. (2016). The United Kingdom: A platform for commercial cooperation. In F.-P. van der Putten (Ed.), Europe and China’s New Silk Roads (pp. 63–71). European Think-Tank Network on China.

- Sun, W. (2010). Mission impossible? Soft power, communication capacity, and the globalization of Chinese media. International Journal of Communication, 4, 54–72. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/617/387

- Szczudlik, J. (2016). Poland on the Silk Road in Central Europe: To become a Hub of Hubs? In F.-P. van der Putten (Ed.), Europe and China’s New Silk Roads (pp. 45–48). European Think-Tank Network on China.

- UK Government. (2015a). Chancellor Makes Historic First Visit to China’s North West. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/chancellor-makes-historic-first-visit-to-chinas-north-west

- UK Government. (2015b). UK–China Joint Statement 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-china-jointstatement-2015

- UK Government. (2016a). Consul General’s speech at Fund Forum Asia 2016. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/consul-generals-speech-at-fund-forum-asia-2016

- UK Government. (2016b). 12th UK–China Joint Economic and Trade Commission (JETCO) Outcomes Paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/12th-uk-china-joint-economic-and-trade-commission

- Valieva, J. (2018). Cultural soft power of Korea. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 7(4), 207–213. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v7i4.1837

- Wang, J. (2018). What were brough by the 10000 trains along the Trans-Eurasia line? Sohu News. https://www.sohu.com/a/250336905_162281

- Xinhua News, China. (2015). Xi Jinping on Chinese soft power. Xinhua News. http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/2015-06/25/c_127949618.htm

- Zhao, S. (2009). The prospect of China’s Soft power: How sustainable. In M. Li (Ed.), Soft power: China’s emerging strategy in international politics (pp. 247–266). Lexington.

- Zhao, Y. (2013)., China’s quest for ‘soft power‘: Imperatives, impediments and irreconcilable tensions? Javnost – The Public, 20(4), 17–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13183222.2013.11009125