ABSTRACT

The Venezuelan economic crisis, combined with the creation of the Orinoco Mining Arc (OMA), has pushed thousands of people to work in wildcat mines in the Venezuelan Guayana. Even though attempts have been made to control illegal mining in the past, the absence of planning and lack of concrete economic alternatives have made these efforts unsuccessful. Spatial planning could play an important role in developing a rural regional strategy aimed at making other livelihood options available. This is a challenging endeavour, however, because the Venezuelan Guayana is the largest and least populated region of the country, with most of its surface covered by fragile forests rich in ecological and cultural diversity. Moreover, data to inform decision-making are unavailable or severely limited. This paper presents an approach that attempts to overcome those obstacles and seeks to identify which are the peripheral remote areas where resource extraction and its negative externalities are most present, conflicting with the preservation of the forest, its biodiversity and the livelihoods of Indigenous populations. The conclusions presented here might assist spatial planners and policymakers who seek to explore territorial approaches for rural development and inform decision-making in peripheral regions where data are scarce.

INTRODUCTION

When a country depends exclusively on the extraction of non-renewable resources, it faces a wide range of risks that can be extremely difficult to manage, since they are created by powerful external factors (Brenner, Citation2014; Sassen, Citation2014). The astronomical rise of mineral commodities over the past two decades has put great pressures on resource-rich countries, tempting both states and individuals to extract the natural resources that lie underground. In this context, Venezuela, a nation that has mainly depended on oil extraction since the 1920s, followed a similar path.

Pushed by the drop of oil prices in 2014, the Venezuelan government decided to shift its attention from the oil fields of the country to the forests of the Venezuelan Guayana, where large deposits of iron, bauxite, gold, diamonds and many other minerals can be found. In February 2016, the government of Nicolás Maduro created the Orinoco Mining Arc (OMA) with a presidential decree (República Bolivariana de Venezuela, Citation2016). This executive order opened 110,000 km2 of savannas and tropical forests in the northern part of the region for the extraction of natural resources, becoming the largest mining project in Venezuelan history.

Meanwhile, the number of illegal small-scale gold-mining operations has increased dramatically in the region since the beginning of the 2000s, and it continues to escalate to this day (Lozada, Citation2016). Illegal mining is a widespread phenomenon in Amazonia, but according to a report published by RAISG (Citation2018), the number of illegal small-scale mines in Venezuela is greater than in any other South American nation. The lack of employment opportunities throughout the country, prompted by the ongoing economic crisis, has pushed thousands of people to work in wildcat mines in the Venezuelan Guayana (Ebus, Citation2018; Rosales, Citation2017, Citation2019). Today, out of 2312 sites with illegal mining activities identified throughout the nine Amazonian countries, 1899 can be found in this region (RAISG, Citation2018).

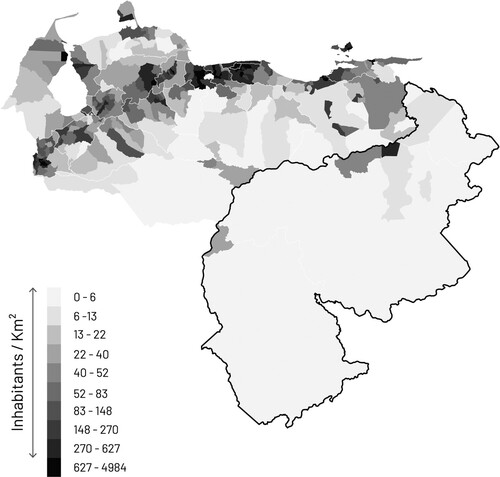

The rise of illegal mining is a worrying trend, since the environmental, social and economic externalities of this type of economy have profound and long-lasting consequences that will be felt by many generations to come (Blanco Dávila, Citation2018; Ebus, Citation2018). More than 80% of the surface of the Venezuelan Guayana is covered by fragile forests with some of the richest and most biodiverse ecosystems in the world, where several Indigenous peoples live in their ancestral homelands (Huber, Citation2001). It is therefore important that the forest be preserved and that Indigenous knowledge is not lost, especially in the context of climate change. Attempts have been made in the past to control illegal mining (Lozada, Citation2016), but the imposition of restrictions without concrete economic alternatives have made these efforts unsuccessful (Prat, Citation2012). Spatial planning could play an important role in supporting sustainable rural economies and in developing a rural regional strategy aimed at making other livelihood options available. This is a challenging endeavour, however, given the fact that this is the largest and least populated region of the country (), with sparse settlements, poor accessibility and low population densities that hinder the provision of basic services and infrastructure in remote and peripheral areas. These conditions ultimately constrain business development and perpetuate existing economic dependencies. Moreover, data to inform decision-making are unavailable or severely limited.

How can spatial planners and policymakers inform themselves when dealing with peripheral regions where data are scarce or unavailable? This paper presents an approach that attempts to overcome those obstacles and seeks to identify critical locations where action might be urgently needed, providing useful insight for policymaking, spatial planning and territorial development strategies, ultimately contributing to understand what the role of spatial planning might be in overcoming economic dependencies in fragile regions such as Amazonia.

PERIPHERALITY, ECONOMIC DEPENDENCIES AND ENVIRONMENTAL PRESERVATION

In Venezuela, most of the debate has centred around the problems created by mining in the Venezuelan Guayana, particularly in the social and environmental sciences. But there is a gap in the study of the regional dimension and the limitations posed by inaccessibility and environmental legislation to the economic development of places.

Historically the Venezuelan Guayana has been considered a peripheral region, disconnected from the rest of the country. It is therefore important to clarify what is understood by this term. Research on peripherality defines a peripheral region as an area with low accessibility, to both economic opportunities and the existing transport network (Schürmann & Talaat, Citation2000, Citation2002). Other authors emphasize low population densities as another important factor, since it can constrain business profitability and development, household income, and local service provision (Davies & Michie, Citation2011). Together, these factors force individuals to travel long distances to reach public services or employment possibilities, but also better educational and social opportunities (Davies & Michie, Citation2011).

The notion that employment, educational and social opportunities are characteristic of disadvantaged places with conditions of peripherality resonates with an argument made by Dourojeanni (Citation1999), who states that lack of social improvement opportunities can still be considered one of the main causes of deforestation in Latin America, forcing the poor to depend on slash-and-burn agriculture, logging and small-scale mining to survive. This tension between peripherality and dependency on unsustainable practices puts the preservation of ecosystems and biodiversity in jeopardy, even within the boundaries of legally protected areas.

Indeed, an important part of the illegal mining operations in the Venezuelan Guayana are located in protected areas, compromising the efforts made by the Venezuelan state for more than 80 years to safeguard ecosystems, landscapes and geographical features with unique scientific and ecological value. There are 30 different areas under special regimes of administration in the region, with differences in terms of land-use regulations and conservation goals (González Rivas et al., Citation2015). The government has historically favoured normative models of rigorous preservation that do not consider a productive dimension (González Rivas et al., Citation2015). But according to the local population, the prohibition of mining and logging activities undermines the economic development of the region (Huber, Citation2001), since these activities are highly profitable and natural forest management is not (Dourojeanni, Citation1999).

The rise of illegal mining creates a wide range of problems beyond deforestation. The erosion of riverbeds and banks, water pollution, the outbreak of malaria, the rise of criminality, and the deterritorialization of Indigenous peoples are all by-products of illegal small-scale mining in the region (Blanco Dávila, Citation2018; Ebus, Citation2018; Moncada Acosta, Citation2017; RAISG & InfoAmazonia, Citation2018; Red ARA, Citation2013). From an ecological perspective, this uncontrolled form of extraction is having far-reaching consequences. The soils of the Venezuelan Guayana are very poor and have extremely low levels of fertility, and if a part of the rainforest is destroyed, the soil does not have the capacity to support the regeneration of that area and primary forest species will only be able to grow again after very long periods of time (Huber, Citation2001).

Several attempts were made by the government of Hugo Chávez during the first decade of the 2000s to control illegal mining in the region (Lozada, Citation2016). One of these programmes, the Mining Reconversion Plan of 2006, encouraged thousands of small-scale miners to abandon resource extraction and engage with other economic activities, such as agriculture and tourism. Efforts were unsuccessful because concrete alternatives were never promoted, and workers returned to the mines driven by the profitability of this activity (Lozada, Citation2016; Prat, Citation2012). Since the decree of the OMA in 2016, no more attempts have been made to control illegal mining. On the contrary, it has created a legal framework that blurs the origins of the gold extracted by criminal groups within its borders (Ebus, Citation2018; Rosales, Citation2019).

Imposing restrictions without both appropriate planning and a regional strategy aimed at making other livelihood options available are doomed to fail. Endogenous growth theory, however, provides insights into what might be needed to promote new economic alternatives in peripheral remote areas. This body of knowledge holds that endogenous or local factors play a very significant role in economic growth, while still recognizing that development is framed by exogenous factors (Stimson & Stough, Citation2008). From a territorial perspective, endogenous development models can be associated with the capacity of local communities to respond to global challenges by making use of the potential that is present in their territory, improving human conditions, increasing the level of employment and alleviating poverty (Vázquez Barquero, Citation2007; Vázquez-Barquero & Rodríguez-Cohard, Citation2018). Human capital, innovation and knowledge are at the core of this model, which emphasizes the role of local initiatives as an instrument of transformation.

The Venezuelan Guayana has a great potential for many biodiversity-based economic activities that go beyond the exploitation of non-renewable resources (Blanco Dávila, Citation2018; Huber, Citation2001). There are interesting examples of local initiatives that already outline an alternative path for a sustainable future in the region (Jiménez Puyosa, Citation2017; ProBiodiversa, Citation2011; SGP Venezuela, Citationn.d.); and most of them have an important environmental dimension aimed at strengthening the capacities of local communities for place-based economic development.

METHOD AND MATERIALS

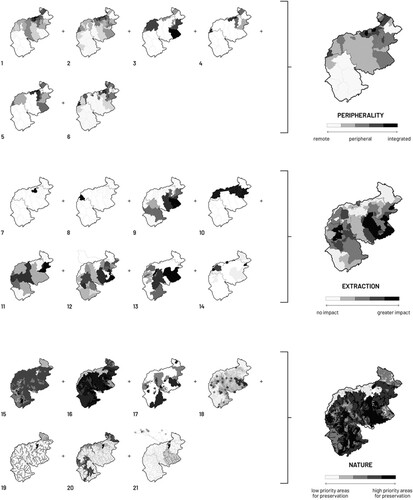

To identify the peripheral remote areas where resource extraction and its negative externalities are most present, conflicting with the preservation of the forest, its biodiversity and the livelihoods of Indigenous populations, a regional-scale analysis through mapping was made with a geographical information system (GIS). A total of 21 indicators that derived from the identification of pressing issues in the literature review were selected around three themes: peripherality, extraction and nature (). The analysis was modelled after the suitability assessment method described by McHarg (Citation1971), which consists of the overlaying of different thematic maps to characterize territories according to a particular scale of values and evaluate the conflicts among them (Deming & Swaffield, Citation2010).

Table 1. Indicators selected for the regional-scale analysis, and their sources.

An important challenge of this investigation was the lack of information and official data that are usually taken for granted in other parts of the world. As Capra Ribeiro (Citation2020) argues, non-existent, lost, outdated, manipulated or even censored information is a challenge that characterizes the contemporary Venezuelan context. For this reason, open-source data produced by international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were complemented and enriched with information retrieved from the literature, online websites, printed cartographies and web mapping services (for sources, see ).

Six indicators were selected to assess the different gradients of peripherality. A global integration analysis, useful to visualize how each street is connected to all others in the national road network in terms of the maximum possible direction changes, was made to understand the ‘level of integration’ (1). The analysis was run with the Place Syntax Tool, an open-source plugin used to perform spatial analyses in GIS, and the resulting median was then transferred to the boundaries of the lowest level of governance – the parish, or parroquia in Spanish. ‘Road density’ (2) was used to provide a more nuanced perspective of the situation, because indicator 1 revealed large areas as integrated ones when only a few centres can be reached by road. The ‘number of airports’ (3) was used to understand which areas are better connected to the rest of the country by this type of infrastructure. The ‘number of health facilities’ (4) was used to understand the ease of accessibility to clinics and hospitals, because many people make long journeys through the region to receive medical care. The ‘number of higher education facilities’ (5) was selected because inaccessibility to educational opportunities may perpetuate inequalities. Finally, ‘population density’ (6) was used because access to other people plays and important role on the creation of social networks and the rise of local initiatives.

Eight indicators were selected to map the areas in which mining has a greater presence, but also the spatial extent of its harmful externalities. The number of iron ore mines (7) and bauxite ore mines per parish (8) were used because the location of these extraction sites has historically provided jobs to large numbers of people, both directly and indirectly. The ‘number of illegal mines per parish’ (9), because it has been reported that there are around 300,000 people who depend on illegal small-scale gold-mining in the region today (International Crisis Group, Citation2019), making this activity a major source of income for many. The ‘area of the OMA’ (10) was chosen because this vast surface of land has been subdivided into large blocks by the national government for new mining concessions, setting the scene for further land degradation and social tensions in the future. The ‘number of illegal mines per watershed’ (11) was used as an indicator because mercury pollution in heavily mined areas is compromising the health of the region’s inhabitants downstream. The ‘number of confirmed cases of malaria’ per municipality (12), because according to the World Health Organization (WHO), the region has one of the highest concentrations of cases in the world. And finally, the ‘number of illegal mines in Indigenous territories’ (13) and the ‘surface of Indigenous lands threatened by the OMA’ (14) were used to measure the vulnerability of Indigenous peoples to violence and forced relocations because of the existence of natural resources on the lands they occupy.

Seven indicators were selected to understand which areas of the natural system are more fragile and should therefore be prioritized for preservation. ‘Soil fertility’ (15), because forests in this region are not supported by rich soils. On the contrary, they are known to have extremely low levels of fertility, and for this reason they have developed adaptive mechanisms to recycle the nutrients from their own biomass (Huber, Citation2001). ‘Vulnerability of ecoregions’ (16), because of the low capacity of the forests to regenerate compared with savannas and other important ecoregions. ‘Legally protected areas’ (17), because they already provide an important base for the preservation of the natural system. ‘Geographical features of unique value’ (18) because of the high level of plant species endemism present in the system of tepui massifs − isolated table-top mountains that can be found in the Guiana Highlands − but also because of the potential they have, along with the waterfalls and water bodies of the region for ecotourism. ‘Major river networks’ (19), because of the role they play in the preservation of the forest and the provision of services to many forms of life. ‘Fragility of riparian land’ (20) was used because of the crucial role these zones have in the reduction of soil erosion and flood control, but also for the reproduction of fish and wildlife. And the ‘boundary of the Caroní River basin’ (21), because the system of hydroelectric dams within this watershed produces 70% of the energy consumed by all Venezuela.

All indicators were mapped, and most of them were systematically evaluated in a gradient of five values with a particular criterion (). For instance, indicator 11 was weighed in relation to the number of illegal mines within the watershed boundaries. River basins with a higher number of mines occupy the highest rank of the scale, while those without illegal extraction sites occupy the lowest rank. Indicators 10 and 21 are boundaries and could therefore not be evaluated with the same ranking criteria. For these indicators, a simplified weighting criterion was used, which gave the highest rank to the areas within the boundaries and the lowest to those that fall outside them. The maps were then overlaid in function of the three themes with Map Algebra, a simple algebra that uses a number of tools to perform geographical analysis in GIS with raster data. The combination of the different raster layers with a basic additive operation resulted in one synthesis map per theme–peripherality, extraction, and nature (). By coupling these results among them with Map Algebra once again, three additional synthesis maps where produced, which show the co-occurrences of high/low values between two chosen themes. The method and the resulting conclusion maps served to have a better understanding of the spatial distribution of different problems in the region.

Table 2. Ranking of the indicators selected for the regional-scale analysis.

RESULTS

The synthesis map of peripherality reveals that the Venezuelan Guayana can be classified into three broad categories: there are integrated and accessible areas in the north, along the banks of the Orinoco River; peripheral areas with low accessibility to basic facilities; and remote areas with a significant lack of basic services that can only be reached by boat or small planes, mainly because they do not have access to the national road network. This latter condition explains why some of the most inaccessible parts of the region have a higher number of airports within their boundaries.

The synthesis map of extraction shows that legal and controlled forms of mining – iron ore and bauxite extraction – are localized and site specific. In contrast, illegal forms of mining – mainly for gold and diamonds – are widely diffused throughout the territory, but predominantly are present in inner parts of the region and in the borderland with Brazil and Guyana. Its harmful externalities are also very diffused, but they go far beyond the areas with a presence of mining activities.

Finally, the synthesis map of the natural system highlights vulnerable areas that should be prioritized for preservation. Most of the region is shown as a fragile environment in the conclusion map. This can be explained by the fact that more than 80% of this region is covered by forests on top of very poor soils.

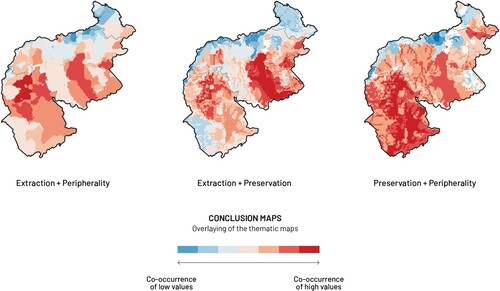

By overlapping the three conclusion maps among them, the co-occurrences of high/low values between two chosen themes could be visualized for different parts of the region (). By overlaying the conclusion maps of peripherality and extraction, for example, remote and peripheral areas with a high presence of mining activities and their negative externalities could be easily identified. Similarly, the overlay of the conclusion maps of extraction and nature helped to recognize which are the areas of the Venezuelan Guayana where the presence of mining activities poses threats to the preservation of highly vulnerable ecoregions with poor soils. And finally, the overlay of the conclusion maps of nature and peripherality allowed it to be pointed out which are the remote and peripheral areas of the region where the natural system is most fragile.

DISCUSSION

The regional-scale analysis identified a number of critical locations in the Venezuelan Guayana where measures need to be taken. These are peripheral and remote areas where resource extraction and its harmful externalities are very present, conflicting with the preservation of the forest and with the safeguarding of unique cultures. Results do not imply that peripherality has a direct influence in the dependency of some communities on resource extraction. Rather, they provide a base to argue that it is an additional factor that needs to be considered to control illegal mining.

The co-occurrence of high values between the peripherality and extraction themes can be interpreted as a symptom of a broader problem in the region. Lack of economic opportunities in marginal areas may be pushing people to engage in illegal small-scale mining to subsist, complicating the preservation of the forest and its biodiversity. Altogether, reduced economic and social improvement opportunities further the current dependency on unsustainable practices in detriment of the forest such as slash-and-burn agriculture, cattle farming, logging, and artisanal or small-scale mining (Lozada & Carrero, Citation2017).

It could be argued that the promotion of economic alternatives becomes crucial in these areas. The sustainable management and processing of non-timber forest products could be explored, but the Venezuelan government has historically opted for normative models of rigorous preservation to safeguard areas throughout the region. Out of 30 legally protected areas, only one biosphere reserve and one forest reserve were created with a productive dimension (González Rivas et al., Citation2015). It is illegal to harvest non-timber forest products inside the remaining 28 national parks or natural monuments, since only passive and low-impact uses such as eco-tourism are allowed within their borders, and this limitation hinders the economic development opportunities of those who live in these places.

Today, the enormity of the protected areas, the centralized structure of the organizations responsible for their management, the restrictive model behind their conceptualization, along with other factors such as rampant corruption and weak law enforcement can be outlined as factors that hamper an efficient administration of these protected areas.

However, endogenous growth theory provides insights into what regional strategies and policies might be implemented to promote local sustainable development in such places. If the inhabitants of remote and peripheral areas have better access to innovation, knowledge, technology and capacity-building programmes, new and existing local initiatives based on the sustainable management of the natural and cultural resources that are present in the territory could grow from the bottom-up in a systemic way. As a result, disadvantaged communities might reduce their vulnerability to external factors. The existing local initiatives identified in the literature review provide an alternative path for a sustainable future. The challenge lies in facilitating the necessary conditions to multiply this type of initiative in order to trigger a virtuous cycle of productivity and self-reliance.

The success of this development model depends on the competitiveness of local initiatives and their capacity to weave networks at multiple levels, working with global value chains and taking part of the international market. For this reason, endogenous growth theory holds that strategies and policies should seek to facilitate the conditions for building local capacities and making local initiatives grow (Stimson & Stough, Citation2008; Vázquez Barquero, Citation2007; Vázquez-Barquero & Rodríguez-Cohard, Citation2018). Institutions should therefore concentrate their efforts in the diffusion of technology, innovation and knowledge, which become an essential requirement to facilitate the transformation of the production system and the first step to shift away from the current state of dependency on resource extraction.

Still, there is not a healthy environment for the implementation of such policies since local and regional institutions have been undermined over the past two decades. The reach and competencies of the Venezuelan Guayana Corporation, a decentralized regional authority created by the central government to develop and manage the national mining industries, were substantially weakened during the years of the Bolivarian Revolution (Prat, Citation2012). Nevertheless, the institution still exists and might provide an excellent base to build upon in future, considering that its successful experience from 1960 to 2005 provided stable employment for thousands of people and improved living conditions throughout the region (Prat, Citation2012).

CONCLUSIONS

The literature review revealed that conditions of geographical and economic peripherality, along with inaccessibility to economic development opportunities, have usually been overlooked, partially addressed or managed in ways that do not deal with the underlaying structural problem. This paper argues that if the regional dimension of this problem is not properly considered, and if viable alternatives are not promoted simultaneously in remote and peripheral areas to overcome economic dependencies, future efforts to control unsustainable practices might be easily lost. In other words, it will be extremely difficult to reach environmental sustainability without addressing socioeconomic issues in disadvantaged areas.

To protect natural areas or to impose restrictions without appropriate planning is not enough. The Venezuelan Guayana may have thousands of square kilometres of protected areas, but in practice the national government has great difficulty taking care of them. In the context of climate change, tensions between development and preservation in regions such as Amazonia demand innovative approaches to rural regional planning.

The regional-scale analysis presented in this paper provides a method with which to identify remote and peripheral areas where unsustainable practices and their negative externalities are most present, conflicting with the preservation of the natural system and thus requiring particular attention. The method leaves room for improvement, because the list of indicators can be expanded depending on the accessibility of data and their assessment can be further refined. Nonetheless, it is useful in assisting spatial planners and policymakers who seek to explore territorial approaches for rural development and inform decision-making in remote and peripheral regions where data are scarce.

Finally, this paper shows that endogenous growth theory provides useful guidance to policymaking and regional planning in remote and peripheral areas. However, the identification of development potentials for rural regional strategies based on this theory, particularly in fragile regions such as Amazonia where the facilitation of conditions for a transition towards sustainability is crucial, remains an open area for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks the Regional Studies Association (RSA) for waiving the article publishing charge. Thanks to Dr Sabrina Lai for her support and guidance during the process; as well as to Dr Fabio Capra and the reviewers for their valuable comments.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

REFERENCES

- Blanco Dávila, A. (Ed.). (2018). Una mirada al soberbio sur del Orinoco: entendiendo las implicaciones del Arco Minero [Special issue]. Explora, 1(1). https://svecologia.org/soberbio-sur-del-orinoco-i-edicion

- Brenner, N. (2014). Implosions/explosions: Towards a study of planetary urbanization. Jovis.

- Capra Ribeiro, F. (2020, forthcoming). Uncertain regional urbanism in Venezuela. Government, infrastructure and environment. Routledge.

- Davies, S., & Michie, R. (2011, October 2–4). Peripheral regions: A marginal concern? [Paper presentation]. European regional policy research consortium, Scotland, UK.

- Deming, M. E., & Swaffield, S. R. (2010). Landscape architectural research: Inquiry, strategy, design. Wiley.

- Dourojeanni, M. J. (1999). The future of the Latin American natural forests (Working Paper). Environment Division of the Inter-American Development Bank.

- Ebus, B. (2018, January 15). Digging into the mining arc. The destruction of 110 thousand square kilometres of forests in the largest mining project in Venezuela. https://arcominero.infoamazonia.org/

- Elizade, G., Viloria, J., & Rosales, A. (2010). Asociación de Subórdenes de Suelo. In P. Cunill Grau (Ed.), Geovenezuela. Cartographic appendix, box A. National maps (map 009). Fundación Empresas Polar.

- Geofabrik GmbH & OpenStreetMap Contributors. (2018). gis_osm_roads_free_1 [Data file from the Venezuela-latest-free.shp database]. http://www.geofabrik.de/

- González Rivas, E. J., Malaver, N., & Naveda Sosa, J. A. (2015). Los ecosistemas acuáticos y su conservación. In A. Gabaldón, A. Rosales, E. Buroz, J.R. Córdova, G. Uzcátegui, & L. Iskandar (Eds.), Agua en Venezuela: una riqueza escasa (pp. 186–251). Fundación Empresas Polar.

- Huber, O. (2001). Conservation and environmental concerns in the Venezuelan Amazon. Biodiversity and Conservation, 10(10), 1627–1643. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012042628406

- Huber, O., & Alarcón, C. (1988). Mapa de la Vegetación de Venezuela. In E. Szeplaki, L. García, J. Rodríguez, & E. González (Eds.), Estrategia Nacional sobre Diversidad Biológica y su Plan de Acción (p. 45). Ministerio del Ambiente y de los Recursos Naturales.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Venezuela. (2014). XIV censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda. Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Planificación.

- International Crisis Group. (2019, February 18). Gold and grief in Venezuela's Violent South. Latin AmericaReport N.73. https://www.crisisgroup.org/

- Jiménez Puyosa, L. R. (2017). Factibilidad institucional para acuerdos de conservación en comunidades del bajo Caura, Estado Bolívar [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], CIDIAT, Universidad de los Andes.

- Lehner, B., Verdin, K., & Jarvis, A. (2008). New global hydrography derived from spaceborne elevation data. Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 89(10), 93–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1029/2008EO100001

- Lozada, J. R. (2016). Una visión histórica de la minería de oro en la Guayana Venezolana. Technical Report. https://www.researchgate.net

- Lozada, J. R., & Carrero, Y. A. (2017). Estimation of deforested areas by mining and its relationship with environmental management in the Venezuelan Guayana. Revista Forestal Venezolana, 61(1), 59–77. http://www.saber.ula.ve/handle/123456789/45222

- McHarg, I. (1971). Design with nature. Published for the American Museum of Natural History [by] Doubleday & Natural History Press.

- Moncada Acosta, A. (2017). Oro, sexo y poder: violencia contra las mujeres indígenas en los contextos mineros de la frontera amazónica Colombo-Venezolana. Textos e Debates, 1(31), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.18227/2217-1448ted.v1i31.4256

- Olson, D. M., Dinerstein, E., Wikramanayake, E. D., Burgess, N. D., Powell, G. V. N., Underwood, E. C., d’Amico, J. A., Itoua, I., Strand, H. E., Morrison, J. C., Loucks, C. J., Allnutt, T. F., Ricketts, T. H., Kura, Y., Lamoreux, J. F., Wettengel, W. W., Hedao, P., & Kassem, K. R. (2001). Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on earth. Bioscience, 51(11), 933–938. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2

- PAHO/WHO. (2018). Malaria incidence map: PAHO health information platform – Malaria surveillance. http://ais.paho.org/phip/viz/malaria_surv_API_popup.asp

- PDVSA. (2018). Arco_Minero_PDVSA_ (ESRI Shapefile, provided by Provita). PDVSA.

- Prat, D. (2012). Guayana: el milagro al revés. El fin de la soberanía productiva. Editorial Alfa.

- ProBiodiversa. (2011). Gestión para el desarrollo agroforestal en la comunidad Piaroa de Gavilán, Estado Amazonas. http://www.probiodiversa.org

- Provita. (2018). ANP_RAISG_VE_180823 (ESRI shapefile). Provita.

- RAISG. (2018). Cartographic data on Amazonia. https://www.amazoniasocioambiental.org/en/maps/#download

- RAISG & InfoAmazonia. (2018, December 10). Looted Amazon. https://saqueada.amazoniasocioambiental.org/

- Red ARA. (2013). La contaminación por mercurio en la Guayana venezolana: Una propuesta de diálogo para la acción. the Red ARA website: red-ara-venezuela.blogspot.com

- República Bolivariana de Venezuela. (2016). Decreto N.° 2.248, mediante el cual se crea la Zona de Desarrollo Estratégico Nacional ‘Arco Minero del Orinoco’ (Gaceta Oficial No 40.855). Caracas.

- Rosales, A. (2017). Venezuela’s deepening logic of extraction. NACLA Report on the Americas, 49(2), 132–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10714839.2017.1331794

- Rosales, A. (2019). Statization and denationalization dynamics in Venezuela’s artisanal and small scale–large-scale mining interface. Resources Policy, 63, 101422. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.101422

- Sassen, S. (2014). Expulsions: Brutality and complexity in the global economy. Harvard University Press.

- Schürmann, C., & Talaat, A. (2000). Towards a European peripherality index. Final report. Institut für Raumplanung, Fakultät Raumplanung, Universität Dortmund.

- Schürmann, C., & Talaat, A. (2002, August 27–31). The European peripherality index. 42nd congress of the European regional science association (ERSA), Dortmund.

- Seguros Caroní, C. A. (n.d.). Listado de Clínicas. https://studylib.es/doc/4659024/

- SGP Venezuela. (n.d.). Programa de Pequeñas Donaciones del FMAM. Acciones locales, beneficios globales. http://www.ppd-venezuela.org/

- Stimson, R. J., & Stough, R. R. (2008). Changing approaches to regional economic development: Focusing on endogenous factors (Working Paper). Financial Development and Regional Economies.

- Vázquez Barquero, A. (2007). Endogenous development. Theories and policies of territorial development. Investigaciones Regionales – Journal of Regional Research, 11(2), 183–210. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ris:invreg:0131

- Vázquez-Barquero, A., & Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C. (2018). Local development in a global world: Challenges and opportunities. Regional Science Policy and Practice, 20181127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12164