ABSTRACT

Conceptualizations of path creation proposed in recent years neglect the role of time and temporal mechanisms. This paper argues that a more comprehensive understanding of inter-path relations that incorporates both agency and relationships among temporal sequences can be achieved using the concept of critical conjuncture, which is overlooked in the contemporary path-creation literature. This paper draws on a case study of the industrial region of Upper Silesia, Poland, where a new regional trajectory is emerging as the result of the unpredicted critical conjuncture of the endogenously driven path of the information technology services sector and the exogenous foreign direct investment-based path of the automotive industry.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

Investigating path creation in old industrial regions (OIRs) has remained at the top of the research agenda in economic geography for several years because of its great theoretical and pragmatic importance. The experiences of industrial regions constitute a fruitful field for theoretical reflections on the central theme in regional studies: Why do some places prosper for a long time and have the capacity for constant renewal while others decline? Meanwhile, the main interest of scholars shifted from the mechanism of lock-ins in the old path towards the processes of creating a new path, what Martin and Sunley (Citation2015) refer to as the ‘developmental turn’. In evolutionary economic geography (EEG), several conceptual mechanisms were proposed, among which branching and related variety were the most extensively developed as the main mechanisms of endogenous new path creation (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018). However, the view of Henning et al. (Citation2013, p. 1357) that ‘the full palette of mechanisms working on different levels in regions’ has yet to be addressed.

Studies on the direction of structural changes in areas of traditional industry show that structural change takes place via gradual evolution towards branches of industry that require higher qualifications and generate higher added value rather than as a radical transition to new knowledge and an innovation-based economy (Cooke, Citation2003). Pike et al. (Citation2010) noted that regions of old industry rarely embark on new development paths but rather follow the trajectory of weak adaptation, strongly burdened with old structures and processes. In a similar vein, Isaksen (Citation2015, p. 597) argued that ‘path renewal and creation in thin industrial milieus can hardly build entirely on scarce regional resources but [instead] demand inflow of [new] technologies and knowledge’. However, a question emerges whether the recently accelerating changes, known as the Fourth Industrial Revolution, or Industry 4.0, does not offer a window of opportunity (WLO) for OIRs, enabling the creation of a new, dynamic path of development. According to the authors of a recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (Citation2019, p. 17) report, ‘Regions in industrial transition have a strong potential to turn opportunities offered by current mega-trends (e.g., digitalization and automation) into regional growth paths’.

The authors follow Tomlinson et al.’s (Citation2019, p. 92) understanding of Industry 4.0,Footnote1 which encompasses the recent trend of ‘digitalization and data exchange in manufacturing technologies’ and ‘includes cyber–physical systems, the Internet of Things, cloud computing and cognitive computing’. All these solutions and technologies change the organization of production and affect the work environment and the number of workplaces (Bailey & De Propris, Citation2019). Isaksen et al. (Citation2020a) argued that digitalization can take the form of digital tools applied in production processes, which is understood as the main product of the Industry 4.0 subsector. Digitalization should be treated as an innovation process (Isaksen et al., Citation2020a) that substantially impacts regional innovation systems (RISs) and renews and transforms existing paths (Isaksen et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). The growth of Industry 4.0 firms requires substantial changes in technologies and RISs, including the support infrastructure, labour market organizations and institutional framework (Isaksen et al., Citation2020a). Technological foundations of digital technologies are said to be globally available (Isaksen et al., Citation2020a) and Industry 4.0 solutions are often provided by external agents such as global information technology (IT) and engineering companies. We question the perspective that is based on the dominant role of external providers of Industry 4.0 solutions.

In this paper we reveal how the development of separate industrial paths has led to the creation of a new industrial path by their intersection (critical conjuncture). By doing so, we rediscover the construct of critical conjuncture as an important source of new paths. We argue that this concept has been overlooked in contemporary path-creation literature.

We argue that the new emerging path that came into being as a result of the intersection of developing maturing paths not only enriches the RIS but also has great potential to be followed, contributing to significant technological growth of the region. By advancing the discourse on new regional industrial path development, this study offers an interesting perspective on restructuring in a post-socialist region. The case represents an untypical transformation of OIRs towards a high-technological Industry 4.0 path. Although the findings may not be applicable to every OIR, it may be very informative for theoretical and conceptual development. We respond to the suggestions of Tan et al. (Citation2020), who postulate multi-actor development and a multi-scalar approach, and take a look at inter-path relations (Hassink et al., Citation2019). Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020, p. 47) concluded that more:

empirical research on the emergence of multiple paths within a region … would undoubtedly produce important insights to complement, refine, and improve the framework, and would help to enhance understanding of how policy actors and the state influence inter-path dynamics.

The constituting new path creation is discussed using the case of development trajectories in the OIR of Silesia.Footnote2 The region is located in south-western Poland, the central part of which forms the second largest (after the Ruhr Valley) polycentric urban agglomeration in Europe, which came into being as a result of hard coal exploitation and processing of steel and non-ferrous metals. The Silesia region is the second highest generator of gross domestic product (GDP) and has the largest concentration of manufacturing in Poland, as well as the largest cluster of coal mining in the entire European Union. The region underwent thorough economic transformations in 1990 and 2000, when over 350,000 jobs in the traditional sectors (coal mining, steel and zinc smelting) disappeared. Surprisingly, in the course of the last three decades, the Silesia region became the largest cluster of new manufacturing industries in Poland, including industrial branches which did not have a long tradition in this region prior to 1989, the automotive industry in particular.

We position the paper within EEG, which has made a substantial attempt to understand how regional structures transform over time and how regional industrial paths are formed and shaped (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006; Simmie, Citation2012). While identifying key regional actors (by looking at agencies), networks (by studying inter-path relations) and institutions, we also refer to the RIS approach (Asheim et al., Citation2019). RIS actors include not only companies and industries operating in the region but also organizations, including knowledge and support infrastructure (e.g., universities, other research and development (R&D) entities, educational providers, etc.); policy actors; and finally, increasingly, users and other actors that impact the innovation processes (Asheim et al., Citation2019). These agents are interwoven through knowledge networks which enable innovation activities.

Numerous studies were conducted in recent years to advance EEG and integrate it with institutional and relational perspectives (Kogler, Citation2015). Recently, there has been a growing area of study that deals with the interrelationships between different pathways. We agree with Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) that, until recently, many papers on new regional industrial path development have mainly been focused on the evolving path in one industry only. However, different industrial paths of the region are interdependent and coevolving (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section presents the state of the art in the field and is divided into three subsections on the factors shaping new path creation, its dimensions, and the types and nature of inter-path relations. Research methods and data are also introduced. The third section contains the results of the empirical study and begins with a synthesis of the directions of economic transformations of the Silesia region in the last three decades; next, the authors review the emerging new path of Industry 4.0. The roles of firm- and system-level agency and labour market shortages in the region are then described. The results are discussed in the following section, followed by the conclusions.

NEW PATH-CREATION AND INTER-PATH RELATIONSHIPS

In the contemporary EEG literature, new path creation is understood from two perspectives. In a broader view, new path creation can be broadly understood as ‘the emergence and growth of new industries and economic activities in regions’ (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019, p. 113). In a narrower view, path extension and path creation are distinguished (Simmie et al., Citation2008; Isaksen et al., Citation2019). New path creation is understood in this approach as the most radical form of path development (although it is often also called new path development; Hassink et al., Citation2019), which involves the introduction of radical new products or services (e.g., self-driving cars; Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019).

Endogenous versus exogenous factors of new path creation

Existing preconditions and the origin of developmental impulses and resources that stimulate the substantial transformation of existing paths or the emergence of new paths should be at the top of the research agenda (Neffke et al., Citation2011). In the past, the literature was dominated by a view that the animation of frequently undiscovered or undervalued local resources was sufficient for abandoning the negative path (Fløysand et al., Citation2012; Isaksen, Citation2009). EEG emphasized the significance of endogenous factors in understanding the mechanisms of local growth. There used to be a strong conviction that internal processes (described by use of the concept of RISs and regional branching) are significant stimulators for the emergence of new paths. Relying on empirical studies, Boschma (Citation2007) argues that the success of new paths depends on the sector similarity mechanism and the use of regional generic resources. The role of local preconditions is still often vital (Fredin et al., Citation2019). For instance, Binz and Truffer (Citation2017) reveal that in the initial phase of path development, some industries show a relatively strong reliance on regional assets. More recently, the significance of regional assets has been acknowledged and their scope has been widened to include more than industrial- and knowledge-related ones (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020).

Thanks to industrial actors and their capacity to impact other individuals (firm-level agency), new firms are set up and novel solutions are provided. With regard to this type, so-called purposeful agents (Simmie, Citation2012), often called knowledgeable actors (Isaksen & Jakobsen, Citation2017), or more specifically Schumpeterian innovative entrepreneurs (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), are claimed to deviate mindfully from existing economic structures (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001). Consequently, such innovative actors may either transform or create new paths (Garud & Karnøe, Citation2001; Isaksen & Jakobsen, Citation2017). However, firm agency alone is not a prerequisite for new path development (Isaksen et al., Citation2019) because companies are affected by system agencies, for example, the activities of non-firms and the impact of regional or national policies. Isaksen et al. (Citation2019) argue that new paths require the combination of both firm- and system-level agency. Path development requires adapting or transforming RISs, made possible due to system-level agency (Isaksen et al., Citation2019). Companies that frequently offer new products have a system-wide capability to innovate (Reischauer, Citation2018) and, as a result, improve system agency. As an element of system-level agency, institutional entrepreneurship (in both its formal and informal dimensions) also matters for path development (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). Institutional entrepreneurs contribute to the creation of new institutions and/or the transformation of existing ones (Battilana et al., Citation2009; Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020), and consequently transform regional industrial paths. Agents who shape institutions include not only policymakers but also some knowledgeable entrepreneurs such as managers of companies, industrial associations or representatives of R&D organizations.

New regional industrial paths may be also based on capital and information resources deriving from other regions (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018; Nilsen, Citation2017). Thus, the emergence of new businesses may be explained in the context of external impulses as the inflow of smart ‘outsiders’ (Fredin et al., Citation2019; Trippl et al., Citation2018): immigrating entrepreneurs, foreign investments (Elekes et al., Citation2019) or relocations of large national companies (Binz et al., Citation2012; Dawley, Citation2014; Nilsen, Citation2017). Outsiders are sometimes said to be triggers for new regional path development (Fredin et al., Citation2019; Hedfeldt & Lundmark, Citation2015). Contrary to Binz and Truffer (Citation2017), drawing on a comparative case study of IT industries in two medium-sized Swedish regions, Fredin et al. (Citation2019) highlight the important role of outsiders in the preformation phase and further development of regional industrial paths. Elekes et al. (Citation2019), in the case of Hungary, argue that foreign-owned firms induce regional structural change and diversification.

To sum up, the issue of the importance of endogenous and exogenous sources of new path creation is far from being completely resolved. Some authors believe that a balance conducive to innovation should exist between local networking and key external ties (Isaksen & Jakobsen, Citation2017; Trippl et al., Citation2018). A recent paper by Miörner and Trippl (Citation2019) discusses how endogenous and exogenous sources can stimulate the transformation of the automotive industry. The study reported that the RIS of self-driving cars was both developed within the region of western Sweden and influenced from elsewhere. New path development has been built upon all three types of system configurations. Miörner and Trippl (Citation2019) argue that not all new knowledge required for transitioning towards a new industry has been developed within the automotive industry. Some important knowledge ties to the self-driving car sector were established with regional industries, mainly the IT sector.

Dimensions of new path creation

There are usually distinguished three dimensions of new path creation. First, it is frequently believed that the development of new paths results from a mechanism relying on a variety of related industrial sectors (branching). Boschma and Frenken (Citation2018) claim that new paths emerge much more frequently in regions whose development relies more on related variety than unrelated variety. For example, Steen and Hansen (Citation2018), analysing the production of energy from wind farms in Norway, show how the dynamics of the development of such a business is shaped by the trajectories of other associated industries. Isaksen and Jakobsen (Citation2017) argue that the development of start-ups or the restructuring of existing companies is insufficient for new path emergence. New paths will appear in regions where, apart from the aforementioned factors, (1) there are related companies, (2) there is a real or potential local demand for products, and (3) there are strongly developed regional assets that derive knowledge from outside the region (Binz et al., Citation2016).

Second, the important dimension of the emergence of new paths is so-called bricolage, which connects multiple actors through networks using dispersed financial resources, materials, information and organizational resources (Boschma et al., Citation2017). These actors have the capacity to unite various organizations and technologies with the aim of constructing joint configurations and coalitions.

Third, the emergence of a new path may be completely independent of internal resources. In such case, the new path is triggered by the transfer and local adaptation of new solutions or activities from the outside (‘transplantation from elsewhere’; Lester, Citation2003). Such import of new technology from the outside, although risky for local development, could consequently contribute to the emergence of a new development path.

Inter-path relationships

The pertinent question formulated by Chinitz (Citation1961), ‘How does the growth of one industry in an area affect the area’s suitability as a location for other industries?’, has recently been reconceptualized by posing the question: How does the development of a new path in the region affect other emerging paths in the same region? It is generally agreed that the emerging industrial paths are interdependent and coevolving (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020). Drawing on the existing literature, we distinguish two types of mutual inter-path relationships (interdependencies) from a temporal perspective:

Diachronic relationships, in which established paths impact new path development.

Synchronous relationships, in which interactions exist between simultaneously developing new paths.

We argue that three main types of diachronic inter-path relationships can be identified as suppressing, enabling and neutral. Most often, the EEG literature on OIR development trajectories discusses cases of old, dominant industries supressing the emergence of new activities. This is a classic theme with well-known concepts such as the upas tree metaphor (Checkland, Citation1976), institutional sclerosis (Olson, Citation1982) and, more recently, multiple lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993). Enabling relationships have been analysed in terms of an inheritance mechanism (Klepper, Citation2002) or a retention and selection mechanism described by Boschma (Citation1997) in his concept of windows of opportunity. On the other hand, neutral relationships have been used either in a concept of unrelated diversity (Boschma, Citation2017) or in simply aspatial approaches as in Arthur’s (Citation1989) ‘pure chance’ models of new industry emergence in the area. At the same time, the relationship between old and new pathways can be considered not only on the enabling–inhibiting axis but also as a sector-oriented process, where old industries in the region shape the emerging industrial mix of new industries. Here, the reference should be made to Massey’s (Citation1984) concept of layers of investment, and in recent years the idea of related diversity by Neffke et al. (Citation2011).

In terms of inter-path linkages, according to Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) three main types of synchronous relationships can be distinguished: competitive, neutral and supportive. Frangenheim et al. argue that the strength of inter-path linkages depends on how they rely on the same/different markets and/or the same scarce or abundant assets. Following Martin and Sunley (Citation2006), Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020) acknowledge that inter-path dynamics may be the result of interactions other than asset- or market-driven ones. However, they do not develop this thread further.

Two previously independent paths may acquire new dynamics, or initiate a completely new trajectory when they enter into a customer–supplier relationship as a result of the emergence of external or internal demand. External demand can emerge as a result of broader technological changes that mark a new development paradigm, or it can originate from political events (Gorzelak, Citation2003). Internal demand can result from emerging constraints on the existing development model of a given industry in the region, for example, shortages in the means of production.

The intersection of prior independent (neutral) paths is described in the classical path-dependence literature as a critical conjuncture. Conjunctures, as Wilsford (Citation1994, p. 257) brilliantly described them, are ‘fleeting comings together of a number of diverse elements into a new, single combination’. The intersection and its timing can have a major impact on the future development of subsequent events. Together they may constitute a major turning point, that is, the intersection may have lasting effects depending on whether they collide at an earlier or a later point in a given trajectory (Mahoney, Citation2000).

To date, the typologies of inter-path relationships developed in the path-creation literature overlook ‘critical conjunctures’ as a source of new paths. It seems this is mainly due to a different conceptualization of the very notion of a path and the mechanisms of its development in relation to the approaches of the classical path dependence studies ().

Table 1. Path creation versus path dependence modes.

A rapidly growing body of literature analysing the creation of new developmental paths has emerged in large part as a reaction to the weaknesses and even dead ends of the canonical version of path dependence. Rigorous, canonical path dependence analysis was the de facto theory that worked well when explaining residual cases and non-generalizable deviant outcomes (Mahoney, Citation2000). The overemphasis on singular, random events often overlooked the impact of agents’ intentional activity. Most importantly, however, canonical path dependence was not in fact evolutionary theory because it failed to deal with systems that evolve from within, assuming that only exogenous shock can cause movement to a new path (Martin, Citation2010; Vergne & Durand, Citation2010). However, it seems that the conceptualizations of path creation proposed in recent years, focused on the role of agency in creating new trajectories, have gone too far ontologically from previous conceptualizations. Any ‘path analysis’ entails investigating relationships among temporally sequenced variables. By contrast, most contemporary conceptualizations of pathways neglect the role of time and temporal mechanisms. We argue that the old concept of critical conjuncture may be a small step towards integrating these two models in order to produce a more comprehensive theory of inter-path relations which incorporates both agency and relationships among temporally sequenced variables.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND RESEARCH METHODS

The analysis relies on three main sources of primary data: personal in-depth interviews, documented studies and quantitative analysis of statistical data. A total of 23 in-depth interviews were carried out, encompassing three main groups of respondents: dynamic companies with domestic and foreign capital that are involved in delivering Industry 4.0 solutions for production companies (nine interviews); companies in the automotive industry implementing Industry 4.0 solutions (10 interviews); and regional stakeholders including, for example, managers of a technical university, an industry cluster, a technology park, and a special economic zone (5 interviews); and the head of the regional business association. The interviewers covered the following topics: strategies of companies and milestones of their development; factors of and barriers to development; forms of upgrading; digital maturity and readiness for Industry 4.0 implementation; features of Industry 4.0 in the Silesia region; and the role of public support. The interviews were carried out between March and November 2019. Two groups of documents underwent the search query: development strategies and other programme documents on the regional and subregional levels, and company documents, including annual financial statements and board of director reports. The background for the analysis was basic statistical data, primarily referring to changes in the number of employees according to industries in the region by NACE 2.0 aggregations. A database of companies active in delivering Industry 4.0 products was constructed, and websites of companies were investigated with the aim of reconstructing firms’ development trajectory.

UPPER SILESIA REGION: ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATIONS OF OIRs IN THE LAST THREE DECADES

The transition to a market economy in Poland after 1989 meant a deep change in the economic trajectory of the OIR of Silesia. The area had to cope with two main challenges: the transition from a centrally controlled economy to a market economy; and the adoption of global changes in late capitalism. Fortunately, due to the strength of regional and national coal mining lobbies, the British scenario, that is, a drastic and shock reduction in capacity and employment, did not occur in the region. At the same time, due to organizational and financial weaknesses, the German model of restructuring based on social consensus, as was the case in the Ruhr region, could not have been implemented in Poland either. As a result, the development of Upper Silesia after 1990 took place in a rather chaotic environment created by the clash of the neoliberal model of the economy with forces acting to maintain the status quo. Overall, the region turned out to be much more resilient than what was predicted in the 1990s and similar regions in Western Europe.

On the most general level, the main direction of structural transformation was related to the increased significance of services at the cost of the mining sector, with a persisting share of the manufacturing industry. In general, three basic stages of transformation of the region’s economy can be distinguished in the last three decades:

Controlled de-industrialization in the 1990s, accompanied by the strong development of services primarily related to filling in the ‘service gap’, in particular in consumer services (severe shortages of services in real socialism) (Domański, Citation2003).

Re-industrialization from the second half of the 1990s, which has continued, with varying intensity, to date. During this period, the driving force was primarily the manufacturing sector, especially branch plants of multinationals, the automotive industry in particular. Investors were attracted to the region by three main advantages: a large labour market with a skilled and motivated labour force; a convenient location to the market; and well-developed infrastructure. The region also became the second largest concentration of logistics services in the country.

The knowledge-intensive new ‘technological’ stage (trajectory) that emerged after 2015. The emergence of this new industrial pathway is discussed in greater detail below.

Emerging new path of Industry 4.0

In the Silesia region, a RIS has been built based on knowledge acquired, managed and transferred by both firm and non-firm agents. As the result of three decades of transformation, three main ecosystems of innovation can be distinguished in the region, after Baron (Citation2016): closed sectoral and territorial ecosystems of traditional industries (coal mining, energy and steel); corporate ecosystems of advanced manufacturing; and an emerging open ecosystem of high-technology industries. In quantitative terms (employment and revenue generated), the advanced manufacturing ecosystem is dominant and growing, while ecosystems of traditional industries will continue to decline, especially under European Union decarbonization policies. The emerging path of open innovation ecosystems appears to have good prospects for further growth.

The high-tech industry is relatively insignificant in terms of employment and firm count (accounting for about 1.4% of total employment in the processing industry). Even taking this limited scale of the industry into account, high-tech may become a catalyst for positive processes of local development, which, in turn, could affect the creation of new competencies and businesses in the future. Development of the high-tech industry in the Silesia region remains strongly selective in space, limited to ‘islands of innovative environment’ (Suchacka, Citation2014), namely main academic centres (Gliwice, Katowice), a cluster of manufacturers of light aircraft in Bielsko-Biała, and few other urban centres where large technologically advanced companies had been located in the period of real socialism (e.g., Tychy).

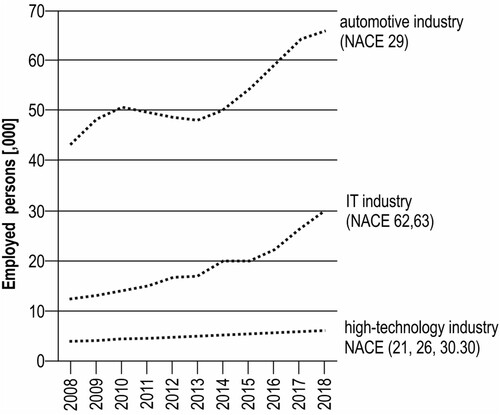

The situation is different in the case of IT and engineering services, which recently became a very dynamic sector in the region (; see also in Appendix A). The information and communication technology (ICT) sector has doubled its importance in the region’s economic base and already accounts for a high share of 4.4%. In Gliwice, the corresponding share has already reached almost 10%, which places the city among the leaders in Poland. A particularly striking process is the emergence of a significant cluster of companies offering Industry 4.0 solutions for manufacturers and its dynamic growth in recent years in the central part of the Silesia region (Katowice conurbation). We argue that Industry 4.0 should be treated as a new technological pathway, due not only to its size but also to the emergence of new companies and complete transformations of the profiles of existing firms. This comprehensive shift from non-advanced IT support to digitalization of manufacturing systems has been observed in many IT companies. Moreover, many sector-specific initiatives and numerous organizations specialize exclusively in supporting the subsector (e.g., centre of competence for Industry 4.0 and the digital hub).

Figure 1. Employment in selected industries in the Silesia region, 2008–18.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on Polish Statistical Office data.

The authors’ estimations, based on searches in various information sources, suggest that in 2020 at least 100 companies offering Industry 4.0 solutions for manufacturing companies were operating in the area of the Silesia region.Footnote3 This is a strongly diversified group of firms, with respect to size, activities pursued and range of operations. The average employment amounts to 35 persons, yet this group includes both large companies (such as, for example, indigenous AIUT in Gliwice, with almost 1000 employees) and micro-companies. About one-fifth of the analysed entities conduct R&D activities. Several dozen companies are currently recognizable players on the domestic or international market (implementations in global OEM and tier 1), offering Industry 3.0 and 4.0 solutions mainly for the automotive industry. The majority of companies, in particular young and small ones, are in the initial stage, which is characterized by building a market position, examining potential directions of development and distributing purchased ready-made solutions. The degree of internationalization is low as of now; about one-third of companies export their solutions, and the level of revenue from export amounts to 11% on average. However, for about 10% of companies, export generates over half their revenue. On top of that, about three-quarters of Industry 4.0 companies are of Polish origin, and the vast majority were established by knowledgeable local entrepreneurs, mainly as spin-offs.

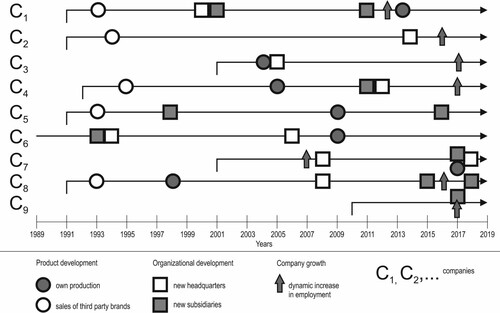

An analysis of development trajectories of nine major indigenous Industry 4.0 providers () confirms that the majority of such companies were created as academic spin-offs, and two originated from the medium-low technology sector. We discovered that a majority developed along the following path: they started as micro-firms that were (re)sellers of other companies’ IT solutions and products or subcontractors to larger companies, usually in basic IT processes (or maintenance services), and later expanded into establishing their own production base (e.g., parts and modules, machines or assembly lines). The development of these companies was possible due to the low entry threshold in the IT sector, and then the possibility of gradual or rapid reorientation, along with a growing demand for IT solutions in manufacturing. This led to the conclusion that regional assets were largely re-used to establish a new regional industrial development path, which diverged from the existing path of IT services. Quick procurement of a large partner or strategic customer conditioned the survival of the studied companies and allowed for acquiring knowledge. Taking into account their operations, companies in the Industry 4.0 subsector illustrate how firm level-agency is influenced by system-level agency (see the next section).

Figure 2. Milestones of development of selected most-dynamic innovative companies providing Industry 4.0 solutions.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on company websites and information obtained during interviews.

Compared with established international companies, Polish integrators are mostly newcomers on the market. The gap in financial and competence potential is an important barrier to entry into the high-margin markets. Thus, an important growth factor is the relatively large domestic market. Nevertheless, the domestic market has significant limitations. It is associated, on the one hand, with relatively weak (so far) demand from companies with Polish capital, and, on the other, with the limited decision-making power wielded by production branches of foreign companies. In general, several domestic companies delivering Industry 4.0 solutions for automotive and other sectors seem to be prepared for the development and implementation of more advanced solutions both at the domestic market and abroad.

Besides tapping into regional assets, some operational and technical knowledge on Industry 4.0 has been brought by outsiders. Intensive learning and competence development processes are associated with the experience gained primarily in the implementation of projects in mature markets, such as Germany. One respondent addressed the question on the factors behind functional and product upgrading by saying, ‘The most important thing was opening up to the world in the beginning of the 1990s. Together with my partner, we worked in companies abroad, we managed to leave Poland. This resulted in knowledge and contacts.’ Competencies acquired abroad were then turned into advantages on the domestic market. The same applied to a limited amount of foreign investment in the automotive sector that in the case of reinvestment introduced Industry 4.0 solutions.

We interpret the phenomenon of dynamic growth of the Industry 4.0 subsector as the conjuncture of two separate industrial paths: the IT sector and the automotive industry (and, to a lesser extent, other branches of the manufacturing industry). It would not be possible without active regional innovation policies and system-level agency, while the labour shortage and wider, external process of technological breakthroughs (digitalization of industry) determined the time of the intersection. Hence, we first describe transformations of these paths as a result of firm-level agency and then move to system-level agency and the role of the labour market.

Firm-level agency and regional industrial paths

After 1990, Silesia became part of one of the largest clusters of the automotive industry in Europe, which spans through the western part of the Małopolska region, the Silesia region and the northern part of the Silesian and Moravian region in the Czech Republic (Domański & Gwosdz, Citation2018; Pavlínek, Citation2017). Four car assembly plants are located in this area: FIAT/FCA, since 1992 in Tychy, formerly FSM (since 1973); GM/PSA in Gliwice (1998), MAN Truck in Niepołomice (2007) and Hyundai in Noszowice (2009); numerous plants of global tier 1 suppliers (including TRW/ZF, Valeo, Lear, Delphi/Aptiv, Tenneco, Nexteer and NGK); and numerous tier 2 and 3 suppliers. At the end of 2019, 205 plants participating in supplies for the first assembly operated in the Silesia region, including 45 plants with Polish capital. In contrast to other clusters of the automotive industry that emerged in Poland after 1990, such as Lower Silesia, which is a simple export platform, the Upper Silesian–Northern Moravian–Małopolska cluster has a complex nature, showing a relatively high capacity for development of non-production functions, which is manifested by R&D and shared-service centres of global (e.g., Aptiv and Standard Cooper) and European (e.g., ZF and Valeo) rank.

From the point of view of the Industry 4.0-based path, the high demand by automotive companies for automated and digital solutions, as well as their high organizational and managerial standards, are of crucial importance. This is well illustrated by a comment by one of the largest Industry 4.0 solution providers, that ‘development of the automotive industry is the great opportunity for IT services and R&D companies. These industries are overlapping and infiltrating each other’ (interview C-6). Thus, a large automotive industry cluster creates a large regional market for companies that supply solutions for Industry 4.0, whereas they are primarily implemented in large plants of foreign-owned companies.

The development of IT services in Upper Silesia is rooted in the historically strongly developed production sector. It was unique in the scale of Poland that already in the 1970s the first computational and analytical centres started to be set up next to industrial plants. At the beginning of the economic transformation, most qualified employees started to leave the existing state-owned companies and set up their own firms (Micek, Citation2008). Several important Silesian IT service companies which operate today were established by former employees of large production companies operating in the high- and medium-high-tech industry. Additionally, academic spin-offs started to emerge on a large scale, even larger than in the metropolitan region of Kraków. Micek (Citation2008) estimated that about 45% of all persons employed in the IT sector in Gliwice worked at such entities. Additionally, urbanization economies (including the presence of significant customers, mainly specialist health institutes, including the Silesian Centre for Heart Diseases, the Heart Prosthesis Institute and the oncology centre in Gliwice) contributed to the development of companies producing software for the medical industry. In comparison with other large metropolitan areas in Poland, many leading foreign IT companies have not operated in Upper Silesia, and their entry to the local market was delayed by over 5–10 years. Over half of the 10 largest IT service centres (with more than 100 employees) emerged in Upper Silesia from 2013 onwards. Currently, large Polish (Future Processing) and foreign (Capgemini Cloud Infrastructure Services, IBM Client Innovation Center, Sopra Steria) suppliers of IT solutions operate here.

Going back to the early 2010s, the changes in some IT companies’ profiles were triggered by growing demand from the manufacturing industry. The relationship between IT services and the automotive industry was an important factor in the establishment of a new path. Starting from arm’s-length collaborative projects, ultimately, interactions resembling interdependencies were observed in the self-driving cars sector in Gothenburg (Sweden) (Miörner & Trippl, Citation2019), including large labour mobility between the two sectors and the emerging subsector of Industry 4.0. Once more, it was due to similar regional assets, represented not only by similar qualified staff but also by the same universities training future employees. To sum up, path diversification of the IT sector in the direction of a new technological Industry 4.0 pathway was possible thanks to a related variety, existing regional assets, knowledge flows from outside and the development of a public-driven side of RIS; in short, new policy instruments and tailor-made organizations.

System-level agency/institutional entrepreneurship

The dynamic development of Industry 4.0 providers would not have been possible without active policies and the engagement of non-firm actors. It was driven by a specific organizational milieu developed around national and regional innovation policies. These trajectories were also influenced by the unique institutional setting of Upper Silesia, characterized by a strong technical tradition, work ethos, specific regional culture and a milieu of trust. All these preconditions created a strong system-level agency.

As the major element of RIS, the crucial institutional entrepreneurs that shape policy instruments primarily include regional stakeholders and, subsequently, government agencies, mainly the Ministry of Entrepreneurship and Technology. Major regional agents include regional authorities (Marshall Office), the Katowice Special Economic Zone (KSEZ), which initiated the Silesia Automotive and Advanced Manufacturing Cluster and higher education establishments, particularly the Silesian University of Technology.

The major public organization that shaped the beginning of the trajectory of Industry 4.0 was most certainly the KSEZ. It was the first special economic zone (SEZ) in Poland to commence advanced activities supporting the anchoring of investors and promoting cooperation for the sake of innovation by establishing the Silesia Automotive Cluster in 2011. It would not have been possible without the prior bulky foreign direct investment (FDI) in this sector. In 2015, the operation of the cluster was extended to companies from the realm of advanced technologies by setting up the Silesia Automotive and Advanced Manufacturing Cluster (SA&AM). The purpose of SA&AM was to build a strong platform for exchange and cooperation among companies and educational and scientific organizations, whereas its activities are focused on two pillars: innovation and cooperation, and labour market and education. The SA&AM cluster initiated a cooperative platform with suppliers of technology for Industry 4.0 called the Digital Innovation Hub and established the Silesian Competence Centre for Industry 4.0 in cooperation with the Silesian University of Technology in 2017. It must be stressed that the activities of the KSEZ are related to a broader process of changing the priorities of the special economic zones in Poland. Before the second decade of the 2000s, these zones were mainly land and infrastructure developers. In the recent decade, with the transformation of national innovation policies, some of them (including KSEZ) managed to transform into the role of knowledge broker.

The second vital institutional entrepreneur shaping the emerging Industry 4.0 path is the Silesian University of Technology in Gliwice. Besides its role as an incubator for the IT sector, as the founder of the first Polish Centre of Competence for Industry 4.0, it coordinates and promotes the development of Industry 4.0. The tasks of the Centre of Competence are mainly focused on educational activities and support for networking among research centres, suppliers of technology, engineering companies and business partners. An in-house training programme, the Industry 4.0 Leader Incubator, was launched at the university.

Coenen et al. (Citation2015) attribute a significant role in the development of new paths of industrial regions to regional strategies. In the case of Silesia, the transition is noticeable from the support of activities directly related to the mining industry. These include restructuring, regeneration of former industrial areas, environmental protection, etc. (e.g., Silesia 2.0 Industry Support Programme of Silesia Province and Western Małopolska; Integrated Territorial Investment Strategy of the Central Sub-Region of Silesia Province for Years 2014–2020) to focus on innovative businesses (e.g., Development Strategy of Silesia Province ‘ŚLĄSKIE 2020+’; Regional Innovation Strategy of Silesia Province for Years 2013–2020; Programme for Silesia, Strategy for Sustainable Development). A common feature of current strategic documents is a long-term striving for change in the regional structure by developing knowledge-intensive industries. Policies focus on enhancing RIS by supporting innovation, creativity and cooperation among universities, R&D entities and companies. Adjusting the labour market (providing training for current personnel and adapting educational offerings) and developing high-quality research infrastructure is emphasized. To sum up, these policy tools are aimed at building more diversified RIS by enhancing existing institutional entrepreneurs, knowledge and support infrastructure.

The role of labour market shortages

The acceleration of automation and robotization in Polish manufacturing and the development of Industry 4.0 in the past few years were largely influenced by the intermediate construct that links firm- and system-level agency, which is the situation in the labour market in Poland. The unemployment rate dropped from 11.4% in 2014 to 5.2% in 2019 (in Silesia from 9.6% to 3.6%). The outcome of a labour shortage was simply stated by one of the managers surveyed: ‘Robotisation and digitalisation is driven by problems on the labour market’ (interview C-4). A representative of a large R&D unit operating in the automotive industry argued that ‘demand on Industry 3.0 and 4.0 is driven by the rising cost of employees and lack of specialists’ (interview R&D-2). This was well summarized by a manager of a firm implementing Industry 4.0 solutions: ‘In response to shortages of employees, demand on automation grew in Polish plants, and that has led to the introduction of digitalization in domestic factories’ (interview C-6).

The main competitive advantages of domestic companies result from the significantly lower labour cost of engineers in relation to the core countries, and geographical and language proximity to clients. For example, spatial proximity translates into quick responses to customer queries (which is a key factor, especially in the automotive industry) and a better understanding of their needs. This can be well summarized by a manager of a global tier 1 automotive supplier: ‘When it comes to expanding, modifying or copying a production line, the local Polish integrator is the most suitable for it. I cannot imagine that it would be done by a foreign contractor’ (interview C-3).

DISCUSSION

OIRs are often caught in the trap of the ‘middle development level’. Their economies grow slower than those of metropolitan areas. OIRs suffer from the burden of heritage, and their structural transformation is a continuous challenge (Birch et al., Citation2010; Campbell & Coenen, Citation2017; OECD, Citation2019; Simmie et al., Citation2008). A few years ago, Baron (Citation2016, p. 74) noted that the Silesia region ‘remains rather a sector of large-scale industrial production than a region of advanced and innovative production with higher added value’. The recent development of the technologically advanced Industry 4.0 ecosystem challenges this picture. The studied region has recently managed to create a new endogenously driven path, relying mainly on knowledge-intensive sectors. The path is still in the process of being constituted, so ‘emerging path creation’ would more precisely describe its current state.

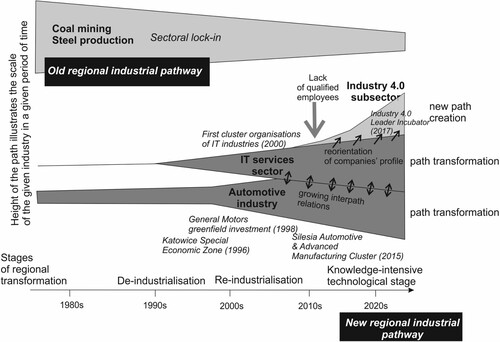

The emergence of the new regional industrial structure was a long-term process: it lasted for about 30 years and had its beginnings in the stage of controlled de-industrialization. In the first half of the 1990s, numerous indigenous IT sector companies were set up by knowledgeable entrepreneurs. Having changed their profiles, these firms subsequently started to successfully offer Industry 4.0 solutions in response to the growing regional demand for such solutions. This demand resulted primarily from the expansion of the automotive industry. Simultaneously, system-level agency exerted a significant influence on path development. In the period between 2015 and 2019, a dense organizational network for the digital transformation of industry was formed by various bodies in the Silesia region. After 2015, their trajectories converged (). The impetus for this process was a substantial lack of qualified workers in the regional and domestic labour market, which rapidly attracted the interest of knowledgeable entrepreneurs to adopt automation and robotization, and the emergence of the Industry 4.0 narrative in public discourse followed by institutions, in the form of legal and organizational regulations, as well as financial support. In effect, a new path emerged in the region. This trajectory has a completely new character, as the role of traditional industrial activities in the region (mining, steel and energy) has become negligible in stimulating the development of new industries.

Figure 3. Regional industrial path development and inter-path relations in the Silesia region.

Note: Important events and organizations in terms of institutional entrepreneurship are shown in italics.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration.

The new regional trajectory results from a conjuncture of various development mechanisms and paths which differ in their scale and scope. First, path creation in the Silesia region was mainly conditioned by the prior emergence of IT, the development of which can be classified, using the typology of Martin and Sunley (Citation2006), as an indigenous creation source of a new path. This development relied primarily on local resources and actions of local actors. Solutions transplanted from the outside via a massive inflow of foreign direct investment were critical for growth in the automotive industry in the 1990s and 2000s. Second, the branching mechanism (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2018) was also important, and relied on related paths, primarily through the relation of the automotive industry with technical competence historically developed in the region and work organization. Third, our analysis reveals that the bricolage came into play (Boschma et al., Citation2017), since a joint coalition for the sake of Industry 4.0 was built by various stakeholders. Such a collage of various actors and resources enabled – at the moment when the window of opportunity related to industry digitalization opened – the creation of a new path. The timing was crucial in this respect; the conjuncture required that all elements were well prepared in order to take place and have a lasting effect. In particular, both the automotive and IT industries in the region and business support organizations (mainly KSEZ) had to achieve a substantial degree of maturity to be able to harness the new technological impulses.

To some extent, the path creation of Industry 4.0 in Silesia is based on similar mechanisms described by other authors, but in some ways departs from clear-cut theoretical explanations and empirical generalizations. Our analysis confirms the results of Isaksen et al. (Citation2019) that new paths require the combination of firm- and system-level agency. Additionally, our result are consistent with those of Binz et al. (Citation2016), who argue that new paths will appear in regions with strongly developed regional assets (even if not purely based on local knowledge), identified branching mechanisms, and facilitative local demand conditions. Our research results also confirm that it is impossible to explain path creation (in its narrow sense) mainly by exogenous factors in the form of inflow from foreign companies, often considered as agents of change. The example of the Silesia region is consistent with the findings of Isaksen and Jakobsen (Citation2017) that local development is driven more by a proper balance between endogenous resources (regional assets) and key external links (more within the scope of flows of external knowledge and less within the scope of capital), whereas novelty is mostly generated locally, albeit with the use of external knowledge.

There are at least two unique or rare features of path development and the RIS in Silesia. First, the case reveals that endogenous regional assets may be substantial triggers for new path creation in the OIR. What is unique in Silesia is the origin of companies delivering Industry 4.0 solutions. Domestic companies that are strongly embedded in the region are the main pillar of the new path. Second, when it comes to RISs, the studied case reveals that RIS in traditional regions can overcome lock-in and evolve from a narrowly specialized to a more diversified RIS. In the case of the Silesia region, such a shift was driven by the development of manufacturing industries and IT services accompanied by new knowledge and the growth of supporting organizations/system-level agency (). It was triggered by a strong institutional setting (regional industrial culture of hard work and an established milieu of trust) and enhanced by institutional entrepreneurs (including the special economic zone and regional university), which spurred many initiatives for the sector (e.g., SA&AM cluster, centre of competence for Industry 4.0 and the digital hub). The same norms and values are shared among knowledgeable entrepreneurs who are enthusiasts for new technologies and support each other.

To date, the newest analysis of inter-path relations was conducted in the framework of the analytical model proposed by Frangenheim et al. (Citation2020), in which the matrix of markets and assets shapes the types of mutual relationships. We argue that the unpredicted critical conjuncture of industries that before the intersection had different markets and used different regional assets may be another source of radical new path emergence. Such an intersection may be regarded as contingent (and, as a consequence, path-dependent), but not in any case an accidental or serendipitous effect of events. It was an unplanned conjuncture of separate industries (by supply links) due to the emergence of inner demand (labour shortage) and outer demand (industry digitalization). The demand could be satisfied by regional IT companies, thanks to their prior development. In this way, both main factors emphasized in the path literature, agency (strongly recognized by path creation) and contingency (a lead theme in canonical path-dependent analysis), played an important role.

CONCLUSIONS

The process of new path creation in the Industry 4.0 subsector in Upper Silesia confirms that the region of traditional industry is not blindly dependent on the legacy of the industrial age or condemned to stagnation in the era of the knowledge-based economy. However, there is no simple and quick way out of old structures and competencies towards a new, innovative trajectory. It took nearly three decades of path transformation for a dynamic endogenous and strongly technological path to emerge in the region. The mechanism behind it was different than in other OIRs and evaded the concepts developed in the path-creation literature. It did not happen through upgrading of manufacturing industries towards high-technology branches or solely through the growth of knowledge-intensive services. In Silesia, the emerging regional trajectory was the result of a conjuncture of two paths: the endogenously driven path of the IT services sector and the exogenous FDI-based path of the automotive industry. Both sectors had become significantly mature before this conjuncture occurred. In the case of the automotive industry, the maturity was associated with the growing position of local subsidiaries in the corporate structure and the waning of basic factors of competitiveness (e.g., cheap, readily available, and motivated labour). The emerging market for Industry 4.0 solutions has been seen not only as a new development opportunity for companies in the IT sector, which in the earlier stages of development built their own competencies and became knowledgeable entrepreneurs, but also as the chance to establish a new industrial regional path. The support of system agency enhanced this tendency.

A factor that cannot be ignored in explaining the case under analysis is the timing of the trajectory convergence. This is because the emergence of a new path, notwithstanding the intentional activity of local stakeholders and the resources they mobilize, occurs in the phase of an opened window of opportunity (in the sense of Boschma’s, Citation1997, WLO model, more so than Scott & Storper’s, Citation1987, interpretation). Relative to the WLO model elaborated by Boschma (Citation1997), our interpretation emphasizes not so much the indeterminacy associated with the unpredictability of where a new concentration of economic activities will develop at the time of external technological breakthroughs but rather the serendipity generated by the unpredictability of the time at which independent trajectories converge. New conceptual understandings linking the contemporary path-creation literature with the concept of windows of locational opportunity may be a fruitful avenue for future research on the nexus between the development of OIRs and the digitalization of industry.

With regard to policy implications, a mix of ‘old’ and ‘new’ policy instruments is required in order to strengthen the new path. In the case of manufacturing industries, system agency should be improved by strengthening the digital maturity of companies. Tools supporting the territorial embeddedness and growth of competencies of foreign-owned enterprises are of key importance in this respect. The greater the decision-making of local managers and the better the position of a given plant in the corporate structure, the greater the possibility of implementing and experimenting with new digital solutions. The development of ‘digital entrepreneurs’ (mainly indigenous small and medium-sized enterprises) could be substantially enhanced by accelerator programs targeted at linking them with big companies, as the first implementation poses a significant challenge. Finally, support for developing the skills required by Industry 4.0 providers is of vital importance.

It is too early to develop forecasts of economic crises caused by Covid-19 pandemics for the emerging path of Industry 4.0. On the one hand, the short- and possibly medium-term demand shock triggered by the pandemics may bring reductions in investments in tangible and intangible assets by the customers of Industry 4.0 solutions, automotive companies in particular. Liquidity problems, faced especially by small and medium enterprises, could substantially slow down the adoption of Industry 4.0 solutions, thus creating an even wider ‘implementation gap’ in the economies of Central and Eastern Europe. The scarcity of labour, which was one of the most important rationales for robotization and digitalization, will most likely cease to be a problem in next few years. On the other hand, the acceleration of digital transport services, digital twin models, e-commerce and systems for supply chain integration could open windows of opportunity for the next digital entrepreneurs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.7 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Industry 4.0 differs from the preceding stage in introducing digitalization of manufacturing, whereas Industry 3.0 solutions are based on automation and robotization.

2 The term ‘Silesia region’ used in this paper refers to the contemporary province of Województwo Śląskie, established in 1999. The historical region of Upper Silesia (including the Upper Silesian Industrial District) forms the central and western parts of the region.

3 It is difficult to identify all such companies because they operate under several codes of economic classification and are classified differently in public statistics.

REFERENCES

- Arthur, B. (1989). Competing technologies, increasing returns, and lock-in by historical small events. Economic Journal, 99(394), 116. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234208

- Asheim, B. T., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Advanced introduction to regional innovation systems. Edward Elgar.

- Bailey, D., & De Propris, L. (2019). Industry 4.0, regional disparities and transformative industrial policy. Regional Studies Policy Impact Books, 1(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578711X.2019.1621102

- Baron, M.. (2016). Open innovation in old industrial regions. Does old mean closed?. The International Society for Professional Innovation Management Conference Proceedings, 1–9. https://www.proquest.com/conference-papers-proceedings/open-innovation-old-industrial-regions-does-mean/docview/1803692383/se-2?accountid=11664

- Battilana, J., Leca, B., & Boxenbaum, E. (2009). How actors change institutions: Towards a theory of institutional entrepreneurship. The Academy of Management Annals, 3(1), 65–107. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520903053598

- Binz, C., & Truffer, B. (2017). Global innovation systems – A conceptual framework for innovation dynamics in transnational contexts. Research Policy, 46(7), 1284–1298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.05.012

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., & Coenen, L. (2016). Path creation as a process of resource alignment and anchoring: Industry formation for on-site water recycling in Beijing. Economic Geography, 92(2), 172–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2015.1103177

- Binz, C., Truffer, B., Li, L., Shi, Y., & Lu, Y. (2012). Conceptualizing leapfrogging with spatially coupled innovation systems: The case of onsite wastewater treatment in China. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 79(1), 155–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2011.08.016

- Birch, K., MacKinnon, D., & Cumbers, A. (2010). Old industrial regions in Europe: A comparative assessment of economic performance. Regional Studies, 44(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802195147

- Boschma, R.. (2007). Path creation, path dependence and regional development. In J. Simmie & J. Carpenter (Eds.), Path Dependence and the Evolution of City Regional Economies, Working Paper Series, Oxford: Oxford Brookes University (Vol. 197, pp. 40–55).

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic Geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2018). Evolutionary economic geography. Oxford University Press.

- Boschma, R. A. (1997). New industries and windows of locational opportunity. A long-term analysis of Belgium. Erdkunde, 51(1), 12–22. https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.1997.01.02

- Campbell, S., & Coenen, L. (2017). Transitioning beyond coal: Lessons from the structural renewal of Europe’s old industrial regions. CCEP Working Papers. Centre for Climate Economics & Policy, Crawford School of Public Policy (Vol. 1709, pp. 1–18). The Australian National University.

- Checkland, S. G. (1976). The upas tree, Glasgow 1875–1975. University of Glasgow Press.

- Chinitz, B. (1961). Contrasts in agglomeration: New York and Pittsburgh. The American Economic Review, 51(2), 279–289.

- Coenen, L., Moodysson, J., & Martin, H. (2015). Path renewal in old industrial regions: Possibilities and limitations for regional innovation policy. Regional Studies, 49(5), 850–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.979321

- Cooke, P. (2003). Introduction. In P. Cooke (Ed.), The raise of the rustbelt (pp. 1–19). Routledge.

- Dawley, S. (2014). Creating new paths? Offshore wind, policy activism, and peripheral region development. Economic Geography, 90(1), 91–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.12028

- Domański, B. (2003). Economic trajectory, path dependency and strategic intervention in an old industrial region: The case of Upper Silesia. In R. Domański (Ed.), Recent advances in urban and regional studies (pp. 133–153). Polish Academy of Sciences, Committee for Space Economy and Regional Planning.

- Domański, B., & Gwosdz, K. (2018). Changing geographical patterns of automotive industry in Poland. Studies of the Industrial Geography Commission of the Polish Geographical Society, 32(4), 193–204. https://doi.org/10.24917/20801653.324.12

- Elekes, Z., Boschma, R., & Lengyel, B. (2019). Foreign-owned firms as agents of structural change in regions. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1603–1613. : https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1596254

- Fløysand, A., Jakobsen, S. E., & Bjarnar, O. (2012). The dynamism of clustering: Interweaving material and discursive processes. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 43(5), 948–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2012.05.002

- Frangenheim, A., Trippl, M., & Chlebna, C. (2020). Beyond the Single Path View: Interpath dynamics in regional contexts. Economic Geography, 96(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Frankowski, J., & Mazurkiewicz, J. (2020). Województwo śląskie w punkcie zwrotnym transformacji. IBS Research Report, 2020(2), 1–75. https://ibs.org.pl/publications/wojewodztwo-slaskie-w-punkcie-zwrotnym-transformacji/

- Fredin, S., Miörner, J., & Jogmark, M. (2019). Developing and sustaining new regional industrial paths: Investigating the role of ‘outsiders’ and factors shaping long-term trajectories. Industry and Innovation, 26(7), 795–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2018.1535429

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2001). Path creation as a process of mindful deviation. In R. Garud, & P. Karnøe (Eds.), Path dependence and creation (pp. 1–38). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Gorzelak, G. (2003). Bieda i zamożność regionów. In I. Sagan, & M. Czepczyński (Eds.), Wymiar i współczesne interpretacje regionu (pp. 57–77). Gdańsk University, Chair of Economic Geography.

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties; the lock-in of regional development in Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The embedded firm; on the socioeconomics of industrial networks (pp. 255–277). London-New York: Routledge.

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Hedfeldt, M., & Lundmark, M. (2015). New firm formation in old industrial regions – A study of entrepreneurial in-migrants in Bergslagen, Sweden. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift, 69(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2015.1011226

- Henning, M., Stam, E., & Wenting, R. (2013). Path dependence research in regional economic development: Cacophony or knowledge accumulation? Regional Studies, 47(8), 1348–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.750422

- Isaksen, A. (2009). Innovation dynamics of global competitive regional clusters: The case of the Norwegian centres of expertise. Regional Studies, 43(9), 1155–1166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802094969

- Isaksen, A. (2015). Industrial development in thin regions: Trapped in path extension? Journal of Economic Geography, 15(3), 585–600. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu026

- Isaksen, A., & Jakobsen, S. E. (2017). New path development between innovation systems and individual actors. European Planning Studies, 25(3), 355–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1268570

- Isaksen, A., Jakobsen, S.-E., Njøs, R., & Normann, R. (2019). Regional industrial restructuring resulting from individual and system agency. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 32(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Isaksen, A., Langemyr Eriksen, E., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2020a). Regional industrial restructuring: Asset modification and alignment for digitalization. Growth and Change, 51, 1454–1470. https://doi.org/10.1111/grow.12444

- Isaksen, A., Trippl, M., Kyllingstad, N., & Rypestøl, J. O. (2020b). Digital transformation of regional industries through asset modification. Competitiveness Review, 31, 130–144. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-12-2019-0140

- Klepper, S. (2002). Capabilities of new firms and the evolution of the US automobile industry. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(4), 645–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.4.645

- Kogler, D. F. (2015). Editorial: Evolutionary economic geography – Theoretical and empirical progress. Regional Studies, 49(5), 705–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1033178

- Lester, R. K.. (2003). Universities and local systems of innovation: A strategic approach. Presentation at workshop on high tech business: Clusters, constraints, and economic development. Robinson College, Cambridge.

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking Path Creation: A Geographical Political Economy Approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. http://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Mahoney, J. (2000). Path dependence in historical sociology. Theory and Society, 29(4), 507–548. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007113830879

- Martin, R. (2010). Roepke lecture in economic geography-rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. http://doi.org/10.1111/ecge.2010.86.issue-1

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). Towards a developmental turn in evolutionary economic geography? Regional Studies, 49(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.899431

- Massey, D. (1984). Spatial divisions of labour. Macmillan.

- Micek, G. (2008). Exploring the role of sticky places in attracting the software industry to Poland. Geographia Polonica, 81(2), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.2009.2.2

- Miörner, J., & Trippl, M. (2019). Embracing the future: Path transformation and system reconfiguration for self-driving cars in West Sweden. European Planning Studies, 27(11), 2144–2162. http://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1652570

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011). How Do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of New growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Nilsen, T. (2017). Firm-driven path creation in Arctic peripheries. Local Economy: The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit, 32(2), 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094217691481

- Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations. Economic growth, stagnation and social rigidities. Yale University Press.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Regions in industrial transition: Policies for people and places. OECD Publishing.

- Pavlínek, P. (2017). Dependent growth: Foreign investment and the development of the automotive industry in East-Central Europe. Springer.

- Pike, A., Dawley, S., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq001

- Reischauer, G. (2018). Industry 4.0 as policy-driven discourse to institutionalize innovation systems in manufacturing. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 132, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.02.012

- Scott, A. J., & Storper, M. (1987). High technology industry and regional development: A theoretical critique and reconstruction. International Social Science Journal, 112, 215–232.

- Simmie, J. (2012). Path dependence and new path creation in renewable energy technologies. European Planning Studies, 20(5), 729–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.667922

- Simmie, J., Carpenter, J., Chadwick, A., & Martin, R. (2008). History matters: Path dependence and innovation in British city-regions. NESTA Futurlab.

- Steen, M., & Hansen, G. H. (2018). Barriers to path creation: The case of offshore wind power in Norway. Economic Geography, 94(2), 188–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1416953

- Suchacka, M. (2014). Transformacja regionu przemysłowego w kierunku regionu wiedzy: Studium socjologiczne województwa śląskiego. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Tan, J., Hu, X., Hassink, R., & Ni, J. (2020). Industrial structure or agency: What affects regional economic resilience? Evidence from resource-based cities in China. Cities, 106, 102906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102906

- Tomlinson, P. R., Barzotto, M., Corradini, C., Fai, F., & Labory, S. (2019). Revitalising lagging regions: Smart specialisation and industry 4.0. Regional Studies Policy Impact Books, 1(2), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578711X.2019.1621095

- Trippl, M., Grillitsch, M., & Isaksen, A. (2018). Exogenous sources of regional industrial change: Attraction and absorption of non-local knowledge for new path development. Progress in Human Geography, 42(5), 687–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132517700982

- Vergne, J., & Durand, R. (2010). The missing link between the theory and empirics of path dependence: Conceptual clarification, testability, issue, and methodological implications. Journal of Management Studies, 47(4), 736–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00913.x

- Wilsford, D. (1994). Path dependency or why history makes It difficult but not impossible to reform health care systems in a big way. Journal of Public Policy, 14(3), 251–283. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00007285

A

Table A1. Changes in employment in the Silesia region by NACE sector, 2010–19.