ABSTRACT

Some accounts focus on the role of governmental systems in the management of the 2020–22 Coronavirus/Covid-19 pandemic. But studies with such an emphasis have typically taken second place to interpretations of outcomes in terms of cases and deaths based on cultural and demographic differences. In theory, federal systems would seem to have certain advantages in managing pandemics given the presumed ability to co-manage national challenges at the federal level (testing, vaccines, resources, etc.) with local differences in demography and behaviour at the state level. This paper argues that, in the case of the United States, its federal system was central to its failure in managing the pandemic. But rather than an indictment of federalism broadly construed, this was the result of a vision of federalism put into practice since the 1980s reflecting a strict division of powers between the states and the federal government. Rather than partners or collaborators with the federal government, the states became competitors with one another and with the federal government. This was the recipe for failure more than was federalism as such.

INTRODUCTION

With few exceptions, mainly in Asia, most national governments worldwide have been seen by a host of commentators as largely ‘failing’ the test of their organization and competence posed by the 2020–22 Coronavirus/Covid-19 pandemic. This has been put down to a wide range of failures both cultural and governmental. In one case, for example, the ‘failure of the Enlightenment project’ is indicted in which the central state lauded by the main figures in European political philosophy such as Thomas Hobbes, John Locke and Montesquieu – particularly in the UK and the USA – is judged to have failed compared with its East Asian counterparts based in a more collectivist political–intellectual tradition (Murphy, Citation2020). The available empirical evidence for this is hardly convincing as of January 2022. Alternatively, some have noted the revolt of peripheral local populations against an overweening central state (Tuccille, Citation2020) that punishes rather than celebrates a diversity of ‘values.’ Seeing restrictions as worse than the disease, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben suggested that the pandemic was ‘invented’ as a pretext for disciplining populations (Agamben, Citation2021, p. 13). This celebration of ‘liberty’ against mask and vaccination mandates seems evidently ideological and self-destructive in terms of lives lost and damaged. Finally, and similarly, is the claim that central governments, particularly in the United States, based on a ‘vision of neutral administration’ (Howard, Citation2021) emerging since the 1960s, spawned a crisis in public trust and subsequent public paralysis in the face of failure to address ‘political trade-offs’ between health and economy. The failures of the US federal government here seem to reflect the ideological polarization between the two main political parties during the pandemic rather than any longstanding nationwide bureaucratic inertia.

Somewhat less hyperbolically, and more contingently, other authors have identified the geographical tensions inherent in certain systems of governance as central to understanding what happened in the face of the pandemic. The uneven geographical distribution of different socio-demographic groups (age, race, ethnicity) as well as the differential distribution of different local–regional political regimes with distinctive vulnerabilities to the pandemic in terms of, respectively, health conditions and management capacities, are seen as keys to understanding. Thus, Gaskell and Stoker (Citation2020), Delaney (Citation2020) and Ford (Citation2020), just to name a few, identify the crucial role of multilevel governance and the barriers to achieving coordinated management and emergency response, in some cases more than others, as crucial to the outcomes in terms of testing/tracing, lockdowns, deaths, hospitalizations and vaccinations. As the pandemic has persisted it is in fact the last two of these that offer the most interesting evidence relative to the quality of management (e.g., Samuel, Citation2021).

Some governmental systems, therefore, appear to have failed more than others (Baldwin, Citation2021). Of course, the geographical scope of pandemics and emerging challenges such as climate change make governance on a strictly state–territorial basis increasingly difficult. Little events somewhere distant now cause rapid and significant effects elsewhere. Pragmatism rather than adherence to old maxims may be the only solution in such circumstance. Most governmental systems are ill-prepared for this. The utter failure to cooperate very well globally in providing vaccines worldwide in order to prevent dangerous mutations from evolving is exhibit A for the mismatch between problem scope and management reach (Brilliant, Citation2021; The Economist, Citation2021a; Gostin et al., Citation2021; Haseltine, Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2020). But even at the national scale in the United States the tragedy has been evident in the failure to learn from other subnational governments even within the same country as well as from abroad (e.g., The Economist, Citation2022b; Morrow, Citation2022; Stone, Citation2022; Taranto, Citation2022). Most states locked into public health policies that, even while failing, were not abandoned because of ideological attachments and political resentments based in historic inequalities and scientific ignorance (e.g., Gordon et al., Citation2020; Witt, Citation2020; Wright, Citation2021). Among other things, blame-shifting across levels of government and an unwillingness to show political weakness by reversing course have long been noted by students of political crisis management (e.g., Weible et al., Citation2020).

But a more mundane and, it turned out, lethal attachment to initial decisions, made in the face of totally inadequate information, also informed the relative failure in many cases. Different units – states and localities – locked into testing/quarantine, mitigation (distancing, closing public spaces, etc.), suppression (wholesale lockdowns) or doing little or nothing, without much later adjustment to account for changing circumstances and better knowledge (Baldwin, Citation2021, p. 4; The Economist, Citation2022a). Local governments, as largely creatures of state governments under US federalism, had limited autonomy to follow their own practices during the pandemic. At the same time, much more pragmatism was evident in economic policies such as income support and loose monetary measures on the part of central banks (e.g., Ip, Citation2021; Tooze, Citation2021). Effective policymaking may have been more difficult in a pandemic, but it was not impossible.

Whatever the metric, the outcome in the United States has been relatively dire. In terms of excess deaths, the US performance in the pandemic was the worst among all the world’s high-income countries: eight times higher than the average (Achenbach, Citation2022; The Economist, Citation2021e; Mueller & Lutz, Citation2022). As of 20 January 2022, a total of 863,334 deaths in the United States were attributed directly to Covid-19. A total of 1 in 500 Americans had officially died as a direct result of infection by the virus by 8 September 2020, 1 in 463 by the same date in October 2021, and 1 in 259 by 20 January 2022 (Bump, Citation2021; Holcombe, Citation2021; The New York Times, Citation2022). US deaths from Covid-19 doubled in 2021, even with the arrival of effective vaccines early in the year (Chappell, Citation2021). The daily case count in September 2021 was up 316% since early September 2020, and the hospitalization numbers were up 158% from the same date (Beer, Citation2021). These metrics then exploded again in November–December 2021 with the arrival of the Omicron variant. This time, however, the death rate was much lower due to increased immunity and the apparently lower virulence of the strain. The pandemic seemed to be never-ending after hopeful signs in June 2021. Indeed, speculation about further waves of infection in the United States in late 2021 did not seem widely off the mark (e.g., Wilson, Citation2021).

Many other countries at similar levels of economic development had much better numbers in terms of fewer cases and hospitalizations by September 2021, even in the face of the more virulent Delta variant, reflecting in large part the failure of vaccination to reach sufficient people (as a consequence of both limited access in some poorer communities as well as anti-vaccination sentiment more generally) and the hostility to restrictive behaviour (masking, lockdowns, etc.) campaigns in numerous US states (Levitt & Keating, Citation2021). New variants spread as a result. Hospitals were swamped in states such as Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas, Florida and Idaho in late summer 2021. These rates were higher than in early impacted states such as New Jersey and New York in winter 2020 and across a broader swath of states in winter 2020–21 (Evans, Citation2021). A similar geographical pattern was repeated with the more transmissible but less virulent Omicron variant in late 2021 and early 2022 (e.g., Narea, Citation2022; Smyth & Gilbert, Citation2021; Steinhauser et al., Citation2021).

Of declared federal countries, ones with constitutionally defined divisions of political functions between federal and state- or provincial-level governments (covering about 40% of the world’s population), as opposed to ones with multi-tiered governments in which ultimate authority rests in centralized unitary states (such as Spain, Italy and the UK), only Brazil had an overall higher official Covid-19 death rate than the United States as of 20 January 2022 and the United States ranked a very high 19th in death rates out of 223 reporting territories. The deficiencies in the quality of the data available worldwide including in the United States (on the numbers, see, e.g., Worldometer, Citation2022; on data, see, e.g., Tufekci, Citation2021a) should be kept in mind. Reports suggest that the numbers of deaths in India and Mexico (both federal countries) have been significantly higher than official figures suggest (e.g., The Economist, Citation2022c; Jha et al., Citation2022). In terms of vaccination against Covid-19, as of 20 January 2022, 62.9% of the US population over age 12 was fully vaccinated (defined as two shots of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines and one of the J&J) compared with 70.4% of over-16s in the UK, and 70.6% of all adults in the European Union. The US vaccination rate tailed off over the summer of 2021 to one of the lowest overall rates among the world’s wealthiest countries (Lukpat, Citation2021). Although 60.3% of the world’s over-12 population had received at least one dose of the vaccines as of 20 January 2022, only 9.4% of people in low-income countries had received one dose (Ellyatt, Citation2021; Our World in Data, Citation2022). In September 2021, the pandemic had still seemed far from over in light of the surge associated with the spread of the Delta variant. The appearance of new variants (such as Omicron) and continuing low vaccination rates even in countries with relatively easy access did not inspire confidence that the pandemic would soon pass (e.g., Kupferschmidt, Citation2021). The longer the pandemic lasted, the more tenuous the immunity offered by the original vaccines would become (e.g., Cortez, Citation2021).

The present focus, then, is on the governance of the pandemic we have all been experiencing over the past two years or more and, more specifically, the relative merits of the actual decentralized versus a prospectively more centralized response in the United States as a diagnostic case. So, as the world slowly begins to recover from the pandemic in 2022, how will different regions and localities cope and respond in terms of what they have learned given the different institutional settings in which they are located? More specifically, I am interested in the role of US federalism in what has been widely seen by many commentators in the country as a chaotic response to the pandemic from the outset. Much of this has been laid at the door of the Donald Trump administration from February 2020 to January 2021 and the so-called transactional federalism (or reward some and punish others) that was used to try to find a role for the federal government in the face of a myriad of approaches adopted by the governors of the different states (Agnew, Citation2021). But until September 2021, when he finally proposed a national vaccination mandate, President Joe Biden had also essentially deferred to the states, suggesting how much it has been institutional bias against federal action since the 1980s more than the individual activity or not of the occupant of the White House that has been at issue (e.g., Healy et al., Citation2021). Of course, much of the pandemic response was already in place when Biden came to office and the potential ire and mobilization of Trump supporters, in the wake of electoral defeat, also limited what was possible in many states (Shear et al., Citation2022).

My claim here is that the very recourse to the patronage method under Trump is indicative of the great difficulty that the current federal system has faced in managing a nationwide crisis such as a pandemic. Of course, over the period January 2020–January 2022, different countries have been seen as having had the ‘best’ management only to subsequently disappoint. Thus, both the US and the UK were lambasted early on, but over the course of the summer of 2021 with their successful vaccine rollouts, they had risen up the charts in numbers of vaccinations. At the same time, of course, the pandemic certainly is not yet over, so any conclusions must be based on incomplete data. Over the next months, interpretations may shift to account for a longer timeframe. It looks very much that in terms of deaths, this pandemic has been much worse worldwide than we were thinking it was in early summer 2021 when vaccination rates in the United States, Europe and other scattered parts of the world were on the upswing and the highly transmissible Delta and Omicron variants had not yet spread widely. That said, it seems clear that the current range of governance arrangements worldwide have been subjected to a common test. This is the context in which I am hoping to make a contribution to discussion about how well different types of governance have responded to the pandemic and consequently what can be learned from this for future challenges such as other pandemics, climate change and other disastrous crises.

Some caveats and limitations on what follows bear emphasis at the outset. First, the agenda of centralization–decentralization obviously must include so-called unitary states as well as ones labelled as federal in order to reach even tentative conclusions about the relative merits of federal systems in the management of the pandemic. Second, much of the readily available data come from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), so much of the world (including large countries such as Brazil and India) is still missing from the discussion here. Third, the United States is something of an outlier globally in relation to the pandemic in respects other than the nature of its federal system. Critically, for example, only Russia has had a higher and as persistent a level of so-called vaccine hesitancy as the United States across a wide range of countries (The Economist, Citation2021b). Much of this hostility to active measures in managing the pandemic may be attributed to their politicization by Trump while president and his clear dismissal of expert knowledge as the pandemic developed. Public health expertise has been explicitly pilloried across states controlled by the Republican Party (Baker & Ivory, Citation2021). In addition, however, an overall pre-existing low level of trust in the federal government by segments of the population persisted, particularly, but not entirely, among white people in the South and West worried about their status within an ethnically changing country (Packer, Citation2021). More generally, the failure of US armed interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 based in either fabricated or poor intelligence and on subsequent managerial incompetence has not helped the reputation of the federal government at home (e.g., Luce, Citation2021). The United States is also an increasingly unequal country in terms of income and access to public goods and services (and relative to other developed countries), including public health services. Therefore, it is not too surprising that it has been older and poorer people (particularly among minority groups such as Latinos and African Americans) that have had the highest rates of hospitalization and death (Abedi et al., Citation2021; Brownson et al., Citation2020; Islam et al., Citation2021). Fourth, and reflecting these social realities, to the extent that is possible, it is best to focus on pandemic management indicators such as vaccination rates, rates of hospitalization and so on rather than just on outcomes such as death rates and caseloads, that can reflect demographic and economic characteristics (age distributions, numbers of people in care homes, ethnic indices, etc.) more than management per se, so as to identify the more specific role of governance in the pandemic.

The paper emphasizes an empirical overview of the course of the pandemic in the United States with a focus first on the overall number of cases nationally between January 2020 and January 2022 and a description of how different states and regions experienced this onslaught. This sets the scene for a subsequent analysis of the state-by-state course of vaccination rates between January 2021 and January 2022 as a key indicator of management of the pandemic. This is then developed further in an exploration of the geography of vaccination–Delta variant complex (how low vaccination rates led to the spread of the variant and fuelled hospitalizations and deaths) in late summer 2021 as illustrative of the costs of state governments not learning from one another and seeing the federal government as an opponent more than a collaborator in managing the pandemic. The second section briefly addresses a number of the putative explanations offered for the spatial variation in the management of the pandemic at the state level that do accept an overall diagnosis of failure in terms of the national response but do not typically deal with the federal–territorial nature of the pandemic. Third, therefore, if these are inadequate or problematic as complete interpretations of what has happened, what is it about US federalism that has produced the distribution of managerial outcomes noted in the first section? In theory, federal systems could be expected to perform better in a pandemic than unitary ones by combining national economies of scale and leadership in many respects (such as developing and deploying vaccines) with sensitivity to local and regional demographic and attitudinal differences. So how well, particularly early in the pandemic, did a range of federal systems perform relative to unitary ones? Asking this question, given the overall focus of this paper on the US, also requires a brief discussion of how US federalism has mutated since the 1980s towards the dualist vision of an absolute division of labour between federal and state governments. This had prevailed before the Civil War but had been in abeyance particularly from the 1930s to the 1980s as a result of the Great Depression and the New Deal, the Second World War and the Cold War empowering the federal level. Since the 1980s and in line with the increased party polarization of US national politics, the dualist vision has made a stunning comeback (e.g., Bulman-Pozen, Citation2014; Schapiro, Citation2020).

It is this vision of federalism and its current practice, I allege, rather than federalism tout court that lies behind the US national failure. This leads into a discussion of what it was about this vision that produced the problematic national outcome in the pandemic. In plugging the gaps in the dualist system, the Trump administration developed a patronage-based model of transactional federalism that failed to compensate for the limits of the existing system. A concluding section claims that the balance within the system could shift back towards a more coordinative and less dualist vision. This is the main lesson from the pandemic experience. But this seems unlikely currently given the extreme polarization of US electoral politics between an extremely anti-federalist Republican Party deeply ensconced in the southern and western regions of the country and a more federalist-friendly Democratic Party that is disadvantaged within the federal system of government (particularly in the US Senate and in presidential politics because of the Electoral College and the courts). The United States may not be too big to govern, but it will require fundamental political–institutional change in the federal system to overcome the real limitations revealed by the pattern of mismanagement of the 2020–22 pandemic.

TERRITORIAL ASPECTS OF THE 2020–22 PANDEMIC IN THE UNITED STATES

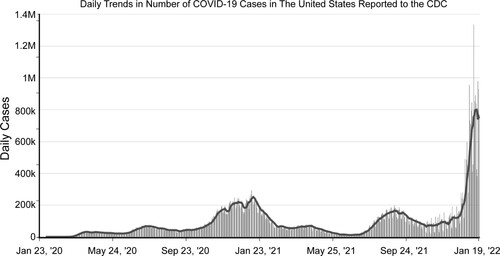

The 2020–22 pandemic has gone through five phases in the United States (similarly elsewhere) in terms of overall caseloads (daily cases) and the geography of the peaks of infection (). In terms of cases of people testing positive for the coronavirus, the first peak was in April 2020, with most cases concentrated in the Northeast, Washington State and hotspots nationwide. The second peak was in August 2020 with community spread leading the way with concentration in Florida, the prairie states such as North and South Dakota, and continuing onslaught in the Northeast and to a lesser extent on the West Coast. The third and highest peak of December 2020–January 2021 drew in much of the country with the highest rates in California, the Midwest and the Northwest. The onset of vaccination programmes in January 2021 saw an attenuation of the pandemic (with a brief upswing in states with low vaccination rates and an absence of regulation of public spaces in March–early April 2021). The fourth peak, associated with the spread of the Delta variant, had its major impact in those states with the lowest vaccination rates, poorest enforcement of anti-virus protocols and limited hospitalization facilities, expanding rapidly between 1 June and 24 July 2021 (going from 20% to 90% of all cases): Florida, Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho and rural Oregon (e.g., del Rio et al., Citation2021; Jain et al., Citation2021). On 7 September 2021, officials in Idaho were forced to ration hospital beds for the first time in the state’s history (Hawkins et al., Citation2021). Alaska, an early leader in vaccination, followed suit later in September as the vaccination rate slumped and the Delta variant arrived in force (Slotnik, Citation2021). The fifth phase associated with the Omicron variant led to a dramatic increase in cases nationwide, if initially concentrated in the Northeast in late November–late December 2021. It hit hardest in states and localities with the lowest vaccination rates. Its high degree of transmissibility was fortunately not matched by its virulence in producing serious disease, particularly in the vaccinated. So, the dramatic increases in cases were not matched, except in places with large pools of the unvaccinated (such as Florida, Georgia, Louisiana and Mississippi), with proportionate increases in hospitalizations and deaths as in earlier phases or waves of the pandemic (Muller, Citation2022; Nirappil, Citation2022; The New York Times, Citation2022; Walsh, Citation2022). Nevertheless, the number of deaths in late January 2022 reached the highest level nationally since February 2021 reflecting both the dramatically increased volume of cases () and persisting pockets of the unvaccinated (Kamp, Citation2022). No clear ‘end’ was in sight even if the Omicron variant seemed less devastating than earlier ones (Lin & Money, Citation2022; Murray, Citation2022).

Figure 1. Daily positive cases for Covid-19 in the United States, 23 January 2020–20 January 2022.

Source: Author from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, https://data.cdc.gov/Case-Surveillance/United-States-COVID-19-Cases-and-Deaths-by-State-o/9mfq-cb36/data

Therefore, the pandemic had a definite geographical imprint over its first two years. Through the first three peaks this had much to do with, in the first instance cases coming into the country from outside, and then community spread depending on such factors as the distribution of vulnerable populations (people in care homes, the aged, etc.) as well as the distribution of mitigation measures such as masking and lockdowns. In 2021, however, it was the rate of uptake of vaccines that seems to have driven down the incidence of cases, hospitalizations and deaths (e.g., Pierson et al., Citation2021). At least latterly, then, it was the onset and delivery of vaccinations that was the main driver of the variegated geography of the pandemic. Despite the existence of so-called breakthrough infections of the vaccinated with new variants (the Delta variant in particular), the overwhelmingly majorities of hospitalizations and deaths by summer 2021 were down to infections of the unvaccinated including increasing numbers of younger people, among them children under 12 with no availability of vaccines. These were overwhelmingly in states with low vaccination rates and lax or missing protocols to limit community spread (Avila et al., Citation2021; Pierson et al., Citation2021). It is important to note that during the fourth peak and subsequently hospitalizations did tend to include more people with milder symptoms relative to earlier waves. These patients were younger on average than those in earlier rounds (Zweig, Citation2021). But death rates nevertheless trended higher in places with higher rates of hospitalization (Pierson et al., Citation2021). If through the first two waves the elderly (and ethnic minorities) were the primary victims of the pandemic, latterly the impact was more widely spread across age groups and ethnicities.

The federal government in January 2020 had mobilized with a number of pharmaceutical companies to produce vaccines (under Operation Warp Speed) that were not only rapidly produced and tested but also manufactured on a massive scale by December of the same year. All the vaccines, but particularly those associated with Moderna and Pfizer, turned out to give excellent immunity against the early variants of the virus if with much less success in preventing transmission. Crucial, then, was how the vaccines would be distributed and the pandemic brought under control. This is when the federal system was given its most severe test. If during the first three peaks, mitigation measures of various sorts had been the métier of managing the pandemic, the future now depended on the rapid distribution of the vaccines. This and the continuation of associated measures to keep mitigation in place until herd immunity could be established on a local basis by means of vaccination determined the outcome of the fourth phase in the summer of 2021.

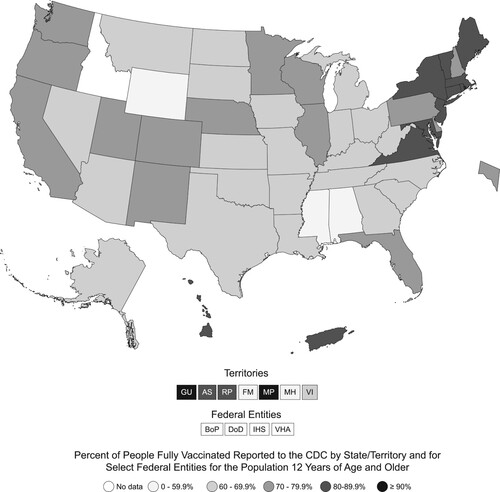

As can be seen very clearly on a map of vaccination rates of the age 12+ populations by state as of 20 January 2022 (), the effective distribution of vaccines into the population has been very uneven. It ranges from very high in states in the Northeast and on the West Coast (plus Minnesota, Colorado and New Mexico) to much lower in the South and in the western states of Idaho and Wyoming. The low vaccination states also happen to be those where there has been most anti-vaccine sentiment relative to population size and where the pandemic has been most politicized as effecting federal overreach by local elected officials (e.g., Fernandes et al., Citation2022; Levitt & Keating, Citation2021; Nirappil, Citation2022). Consistently since the start of the pandemic these are the states (along with Texas and Florida) that have most questioned the messages emanating from federal agencies (such as the US Food and Drug Administration – FDA, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – CDC) and challenged the trade-offs between better health outcomes and temporary economic setbacks that have mainly prevailed elsewhere. So, much of this can be ascribed to cultural/attitudinal differences relative to questioning the reliability of medical expertise and overall distrust of the federal government as well as overinvesting in Trump’s early dismissals of the dangers associated with the virus (e.g., Gonsalves, Citation2021; Kaufman, Citation2021; Morris, Citation2021).

Figure 2. Vaccination rates (percentage of 12+ population) by state (and other units) across the United States as of 20 January 2022.

Source: Author from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) data, https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/reporting-vaccinations.html

But a significant element in it has been the refusal of state and local officials to learn from elsewhere by adopting a pragmatic outlook about the novel challenges to government raised by the pandemic. Instead, they have tended to portray the federal government and its experts as interlopers or outsiders rather than potential collaborators in ending the pandemic. Evidence for this contention ranges from the very different state–government positions on vaccine mandates and masking ordinances to school closures and lockdowns without much change in postures over time (e.g., Griffin, Citation2020; Ivory et al., Citation2021; Leavitt, Citation2022; Mazzei, Citation2022; Wood & Brumfiel, Citation2021). In turn this has undoubtedly extended the pandemic. This extension is clear when counties in the United States as of late July 2021, with major outbreaks and hospitalizations associated with the Delta variant, are mapped with respect to their relative status in terms of vaccination (Cuadros et al., Citation2022; WSTB TV, Citation2021). The overwhelming majority of counties with high rates of outbreak were in very low vaccination states in which state leaders obstructed or discouraged masking, social distancing and vaccination measures. Local governments challenging state rules were often disciplined or sued in court. Hospitals overloaded as a consequence, death rates soared (e.g., Santiago, Citation2021; Williams, Citation2021). Deaths were not just from Covid-19 but also resulted from the collapse in capacity to treat other ailments (Evans, Citation2021). So, the spatial correlation illustrated here strongly supports a causal linkage between the deepening of the pandemic and failure to provide appropriate management equivalently across the country. The end result has been the dire overall performance of the United States, even if much of it seems to be down to a set of the states unwilling to learn from others or coordinate with the federal government.

PLAUSIBLE ALTERNATIVE INTERPRETATIONS OF THE AMERICAN FARRAGO

Before indicting contemporary US federalism, what might be some plausible alternative interpretations? These do not all address the territorial nature of the pandemic, only the overall perception of a failed national response. In brief compass, the predominant ones are as follows.

The first is the relatively inefficient and ineffective US healthcare system (Emanuel, Citation2020; Oshinsky, Citation2020). Relying heavily on private insurance provided overwhelmingly by employers plus the federal Medicare programme for the elderly and the state-administered Medicaid programmes for the poor, the number of hospital beds and healthcare facilities have been dramatically reduced in recent years as provision for healthcare has become as corporate in organization as has its financing (OECD, Citation2020). The typical way of representing this in its entirety is to show how much the United States spends per capita with very poor outcomes (such as life expectancy at birth) compared with countries that spend significantly less (e.g., Scott, Citation2021; Thompson, Citation2021). Although this helps to explain some of the problems with hospital access during the pandemic it is difficult to see how this accounts for all the consequences of the pandemic and their geographical patterning tout court. It also should be noted that it is the western states of the US that hospital capacity has been most reduced (OECD, Citation2020). These are generally not the states with the worst outcomes in the pandemic. Early in the pandemic private insurers also waived deductibles and co-pays so these features of insurance were not a barrier to treatment. As they were restored in late 2020 and 2021, however, this imposed an added burden on the mainly unvaccinated pool of the infected in low-vaccination states looking for hospital based ‘cures’ (Rowland, Citation2021). Perhaps most importantly, the absence of reliable health insurance for perhaps 25% of the population seems to have reduced trust in the overall healthcare system and in the pronouncements of medical experts on matters such as masks and vaccines (Tufekci, Citation2021b). Finally, the public health system across the country has been systematically underfunded for years and has serious deficiencies in coordination and personnel at all levels: local, state, and federal (e.g., Sharfstein, Citation2022; Stacey, Citation2022; Wallace & Sharfstein, Citation2022).

The second interpretation isolates the idea of ‘democracy’ as somehow critical to the management of pandemics, claiming that across a number of pandemics down the years (from 1960 to 2020) the death rates were lower for relatively affluent democracies than other types of polity of whatever gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (The Economist, Citation2020). In this pandemic, however, the correlation does not seem to have that much validity. Indeed, China and a number of other non-democratic regimes seem to have done as well or better than those conforming to a typical definition as ‘democratic’ (periodic multiparty elections, transparent legal systems, etc.) Yet, the corollary does not hold. The variance in performance among all sorts of political system suggests that neither democracies nor dictatorships can claim a singular advantage (e.g., Esarey, Citation2021). Perhaps the most important factor in overall outcomes has been relative trust in government, with countries such as the US doing particularly poorly on this score (Bollyky et al., Citation2022; Taylor, Citation2022).

Third on the list is the more clearly plausible idea from what we know about the course of the pandemic is that the spread of the virus and the relative vulnerability of different population groups (on account of co-morbidities such as obesity and age) account for the outcome (e.g., Goldhill, Citation2021; Lane, Citation2022; Mendenhall & Gravlee, Citation2021). Given the host of socio-spatial inequalities that plague the United States, as noted previously, this is not that surprising. This interpretation acknowledges, therefore, the geography of the pandemic but typically exempts the ways in which management of the pandemic has varied regionally and locally from the equation. Much of the mainstream media coverage in the United States has tended to take this tack. By the summer of 2021, however, this approach was increasingly supplemented by reference to the role of the different state governments in the prolongation of the pandemic. The problematic nature of the federal compact was rarely invoked. Some analyses, while emphasizing the deficiencies of the US healthcare system and the deep-rooted character of social and ethnic inequalities across the country, do manage to show that federalism as practiced failed to live up to its promise notwithstanding the efforts of some states and their governors to effectively manage the pandemic (e.g., Singer et al., Citation2021).

Finally, relatively rarely but with some publicity in ‘conservative’ outlets, such as the editorial pages of Rupert Murdoch’s The Wall Street Journal, have been accounts that lament the declining ‘resiliency’ of US populations compared with times past, presumably when ‘America was Great’, and the overriding need to limit restrictions and declare the pandemic over ad seriatim (e.g., Freeman, Citation2022; Halperin, Citation2022; Henninger, Citation2022; Taranto, Citation2022). In this ideological ‘bubble’ the pandemic was only ever a discursive construction whose main negative effect was invariably economic rather than human. In this vein, the historian Niall Ferguson argued that during past pandemics in the 1950s Americans were both less fearful and more measured in addressing the risks attached to catching any disease in question than they were in 2020–22 (Ferguson, Citation2021). Of course, in those simpler times there was also much less of the misinformation spread by social media and the population was much less polarized politically than it is today. The early claims by Trump and others that the coronavirus was just a new flu that would be over soon also confused many people as to its seriousness. This paralysed many people’s consciousness of the relative risk attached to it (compared with, say, crossing a street or smoking) and probably aided in the extension of the pandemic.

US ANTI-FEDERALIST FEDERALISM AND OTHER FEDERAL SYSTEMS DURING THE 2020–22 PANDEMIC

So, if none of these is adequate in its entirety in explaining the geographical course of cases, hospitalizations, deaths and vaccinations, what is it about US federalism that made the outcomes we have seen likely?

In my view, the story begins in the 1980s (Agnew, Citation2002, Citation2021). During that decade both the US federal government executive branch and the federal judiciary began to question and undermine the stronger role for the federal government in regulation and direct delivery of services to states and localities that had become common from the New Deal of the 1930s to the 1970s. This role has been seen as expressing a ‘polyphonic’ model of federalism in order to stress the complexities of overlapping rather than mutually exclusive jurisdiction between the state and federal governments in various functional areas. So, during the Ronald Reagan presidency the United States began to return to what had been the model of federalism before the US Civil War: one with a rigid division of labour between the states and the federal government in which there should be no overlap and all other powers, other than those specifically given to the federal government in the US Constitution, should be reserved to the states. Partly this reflected the increased reliance of the Republican Party on the votes of those southern whites who viewed the federal government in a dim light as a result of the civil rights and other legislation of the 1960s that potentially undermined their local political dominance. But it was also the result of the turn away from an activist federal government toward the victory of so-called neo-liberal capitalism in which government was seen as the enemy of economic growth and slashing income taxes should be the centrepiece of economic policy. This ‘dualist’ view has been reinforced in the years since by the increasingly conservative cast of the federal judiciary and the popular redefinition of federalism more broadly towards a restricted conception of the role of the federal government outside of narrowly defined parameters (Bulman-Pozen, Citation2014; Schapiro, Citation2005–Citation06).

Amazingly, the main conservative legal organization (created interestingly in 1982), actually called the Federalist Society, has taken up the task of championing what the framers of the US Constitution would undoubtedly have seen as anti-federalism. Its view is of a rigid division of functions between federal and state levels and the sense of the two levels as competitors rather than as co-actors (e.g., Gibson & Nelson, Citation2021). In efforts at shrinking the role of the federal government, therefore, the clock was turned back to a conception of federalism that arguably prevailed before the Civil War, but which might also be seen as embodying the very premises of government based on loose confederation that the US Constitution, at least in the eyes of James Madison and Alexander Hamilton, was designed to overcome.

Americans have long fought over the meaning of the US Constitution and what it entails for the balance between the states and the ‘general’ or federal government. The boundary between the two has always been fuzzy but advocates of ‘states’ rights’ (even though this term nowhere appears in the US Constitution) have turned state autonomy into the highest feature of US federalism rather than emphasizing the need to balance the states’ right to experiment in policy against the need for collective learning and coordination, particularly in emergencies. Much of the controversy concerning the federal government is about the so-called supremacy clause and the extent to which historical change (the coming of the welfare state, total wars, macroeconomic management and so on) mandate revisiting the balance between the tiers of government (e.g., O’Neill, Citation2005; Terbeek, Citation2021). More recently, the entire question of the delegation of powers to federal executive agencies from the US Congress has also been raised to undermine the federal role in managing a wide range of issues from gun control, free school meals, climate change, and water pollution to abortion rights and vaccine mandates (e.g., Greenhouse, Citation2022; Mortenson & Bagley, Citation2021; Sokol, Citation2022).

What seems clear, however, is that the dualist vision of a strict division between the tiers has made a major comeback over the past forty years. Yet a strong argument can be made that this effectively undermines the nationwide pursuit of the very goals of ‘life, liberty, and happiness’ represented by the US Declaration of Independence and enshrined in the US Constitution that the whole is somehow greater than the sum of the parts. In this context, Robert Schapiro has reminded us that the glaring inequalities in income and welfare among the states in the United States are not intrinsic to federalism but a by-product of its present-day malfunction (Schapiro, Citation2020; also see, e.g., Gibson & Nelson, Citation2021). The former FDA Commissioner, Scott Gottlieb, points out that the main federal agency charged with managing pandemics, the CDC, had been hollowed out over the years and left the country without an effective operational national centre once Covid-19 arrived on US shores (Gottlieb, Citation2021). The geographical course of the pandemic further illustrates two distinctive aspects to these features of US governance. One, clearly, is the relative retreat of the federal or general government from coordinating across the states, and the other is the absence of much coordination and learning among the states. Other federal systems, such as Germany, Canada and Australia, seem to have done much better on both counts because of clear institutional channels for collaboration even in the presence of different political parties controlling different levels of government (e.g., Bohrn, Citation2021; Rozell & Wilcox, Citation2020). More specifically, ‘executive power’ across states and provinces in coordination with federal officials trumped partisanship and anti-federal influences in both Canada and Australia relative to the United States (Brown & Latulippe, Citation2021). Even if in Canada anti-federal government protests, such as the ‘Freedom Truck Convoy’ to Ottawa and the blocking US–Canada border crossings in February 2022, suggested weary displeasure with vaccine mandates, they were not widely supported and were financed as much by right-wing Americans as by Canadians of any political stripe (e.g., Mahdawi, Citation2022; Porter, Citation2022). Evidence from across Latin America underlines the vital importance in better outcomes of consultation and coordination across tiers of government irrespective of whether systems are unitary or federal (Cyr et al., Citation2021).

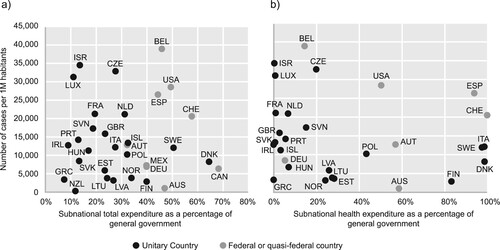

In theory one might expect all federal systems to do better than unitary ones at managing a pandemic: at the same time, you can combine national leadership and economies of scale in acquiring needed resources and leadership with local measures reflecting the needs of different populations (rural/urban, attitudes to disease, health care facilities, etc.) As (covering the first year of the pandemic) shows, this is not how it turned out, although some did better than others (De Biase & Dougherty, Citation2021). The US performance was among the direst across the first nine months. By and large, the federal and the other more decentralized if still officially unitary countries (measured in terms of total subnational and subnational health expenditures) tended to do relatively worse across the first nine months of the pandemic in caseloads than did many of the more centralized countries with clearer central direction and less political grandstanding by regional and local politicians. Belgium did poorly early on (as shown here), partly because of regional animosities, but it later bounced back with a very successful vaccination programme (Vanham, Citation2021). Many other federal systems in large countries, such as Canada, Australia and Germany, though, managed to maintain a more collaborative or ‘polyphonic’ rather than a competitive/dualist approach to governance from the outset (e.g., Fenna, Citation2022; Kropp & Schnabel, Citation2022; Lecours et al., Citation2022). This involves formal channels for negotiating across tiers of government and recognizing that in the contemporary world all sorts of public problems cannot be addressed just at one scale of governance. Overlaps are understood as inevitable and should be managed as such. By and large, outcomes turned out to be considerably better (e.g., Bohrn, Citation2021: Cox Downey & Meyers, Citation2020; Rozell & Wilcox, Citation2020; Steytler, Citation2022). Whatever the precise parameters of the governmental system, clearly defined authority structures across tiers with incentives for ‘collegial endeavor among autonomous actors’ (Cameron, Citation2022, p. 274), such as in Australia and New Zealand, to name just two countries, tended to be significant in overall managerial success across the course of the pandemic.

Figure 3. Federal versus unitary systems in expenditure patterns and Covid-19 cumulative cases (OECD member countries), January–December 2020: (a) cumulative cases versus total subnational expenditures; and (b) cumulative cases versus subnational health expenditures.

Source: Redrawn from De Biase and Dougherty (Citation2021).

Australia makes for a particularly good comparison with the United States as another settler–colonial country, if one with a much smaller population and relative geographical isolation in the context of a global pandemic (e.g., Jackman et al., Citation2020). Not all went well. In particular, in focusing on trying to remain ‘Covid free’, the Australian federal government neglected the introduction of vaccines and thus extended the pandemic unnecessarily given the other advantages the country enjoyed. As of late summer 2021, only around 33% of Australian adults were fully vaccinated. But there was clear collaboration between the states and federal government and there was nothing like the politicization of public health measures such as happened in the United States, partly because US governors opted for such utterly different strategies and seemed to deliberately eschew learning from the experience of other states. By January 2022, the Australian fully vaccinated population had risen to 77.8%, well above that of the United States. Even as the Australian states sometimes defied the federal government on closing their borders and other quarantine measures, they nevertheless collaborated with it and one another to an extent unheard of in the United States (e.g., The Economist, Citation2021d; Fenna, Citation2022).

DUALIST FEDERALISM IN PRACTICE

What about US dualist federalism was most responsible for the problematic national outcome? Several aspects deserve mention. One of the most important is that since the 1980s, state governors’ executive powers have expanded relative to both their own legislatures and the federal government. Governors are no longer the figureheads they often once were (The Economist, Citation2021c). This put them front and centre as the pandemic arrived. Federal governments have long shifted implementation of national policies to the states (e.g., Kettl, Citation2020). In the absence of federal leadership, state governments can pick up the slack (e.g., Wines, Citation2021). They then innovate on all sorts of policies, including those that contradict longstanding federal ones on voting rights, restricting abortion, immigration, legalizing drugs, etc. (e.g., Agnew, Citation2021; Waldman, Citation2021). The road to the White House has also long led through governors’ mansions, but in the context of an increasingly polarized electorate this means that governors are often engaged in national political campaigning as much as they are in governing their own states. During the 2020–22 pandemic, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis was a clear example of this tendency. In many respects, both privatizing federal powers and devolving powers to the states have also hollowed out the federal government. As a result, state officials have also turned challenging federal policies into a central tenet of their power (Adolph et al., Citation2021; Dinan, Citation2020). Attempts at providing government-sponsored health insurance through the states (the Affordable Care Act, or so-called Obamacare) would be a good example. Finally, accountability for managing the pandemic was completely unclear from the outset. The president, governors and various public health officials all vied for attention, but it was never clear if the buck stopped anywhere. They were all working from different scripts.

Cerny (Citation1989) has dubbed the overall trend in the relative diminution of and increased confusion about the role of the federal executive in the United States ‘Madisonian entropy’, combining the framer of the US Constitution James Madison with the idea of dissipated energy. Cerny argues that in the 1930s, following the Great Depression and encouraged by the mobilization for the Second World War and then the Cold War, the US popular sense of common foreign enemies, limited party divisions and the management of the national economy by the federal government jointly led to federal empowerment. This has disintegrated with the end of the Cold War, the shift to neo-liberal economics and the increased ideological division between the two main political parties, one of which, the Republican Party, has become explicitly anti-federalist. The clash of state and federal sovereignty claims has now left even the possibility of federal direction or coordination across levels of government fatally damaged, even for programmes that are widely popular (Allain-Dupree et al., Citation2020; Reiley, Citation2022; Stacey, Citation2022).

Several examples of this clash from the course of the pandemic have received much attention latterly. The failure of a national testing policy for Covid-19 and the lack of a centralized system for tracing variants are good examples of policy areas in which the federal government should have had a net advantage relative to the states. But in neither case did this happen (e.g., Abbasi, Citation2021; Becker et al., Citation2021; Khazan, Citation2020; Koons, Citation2021; Maxmen, Citation2021; Nuzzo & Gostin, Citation2022). A laissez-faire approach prevailed in each of these functional areas, to the extent that with respect to testing, states themselves began to form consortia in the absence of the federal government. With the rollout of vaccines, the pattern of states shooting off in multiple directions without showing evidence of either learning from one another or making the most of federal resources, until circumstances are utterly dire, has continued, as attested to by . The lack of a basic and consistent federal messaging strategy about behavioural norms, such as avoiding closed spaces, crowded places and close-contact settings, was particularly evident early in the pandemic compared with some other countries, such as Japan, which as a result have seen lower death rates and overall socio-economic disruption (e.g., Oshitani, Citation2022).

A final problem area has been the ad hoc way in which data about the course of the pandemic have been collected by the states and then compiled by federal agencies, particularly the CDC. Early in the pandemic, in particular, before the CDC passed under new leadership in January 2021, the ‘optics’ of the numbers were more important to the federal government (and many governors) than understanding the reality of what was afoot. This led to various scandals, such as keeping cruise ships out of port so numbers of cases could be deflated and manipulating numbers or firing officials at the state level whose numbers went against the ideological postures of their governors (e.g., Beason, Citation2020; Gold & Shanahan, Citation2021; Schultz, Citation2020). As the pandemic evolved, there was also limited attention given nationally and state by state to whether metrics such as cases or hospitalizations made more sense as primary measures for determining strategies (Samuel, Citation2021), particularly when with the late 2021 onset Omicron variant, for example, testing positive (if vaccinated) was not typically life threatening and hospitalization was often not caused by the variant but by some other condition, but the variant was present once admitted to the hospital (Khullar, Citation2022).

TRANSACTIONAL FEDERALISM

Arguably, therefore, the federal government was largely missing in action, particularly early on in the pandemic, save for the vaccine financing and various agencies’ efforts at helping with field hospitals. What the country experienced instead was what a number of people have called ‘transactional’ federalism in which the federal government singled out governors for punishment or reward depending on their partisan affiliations and premature decisions to open up their economies rather than actually managing the pandemic (Bowling et al., Citation2020; Williamson & Morris, Citation2021). In this regard, the United States exhibited what has been called a commitment to ‘medical populism’ (Lasco, Citation2020) in which the president and many officials staged the pandemic as a performance opportunity in pursuing their rhetorical demonization of experts and bureaucrats who remained more the enemies of ‘the people’ than the pandemic itself. Rather than establishing and then adjusting a national plan, they engaged in daily routines (such as press conferences) mainly directed at criticizing their political enemies more than mobilizing and organizing against the spread of the virus. The outcome was the poor pandemic management and coordination alleged at the beginning of this article.

Arguably, in pursuing a transactional strategy in the absence of mechanisms for coordinating with other tiers of government in a concerted and organized manner, the Trump administration was adhering to an approach to governance that Trump himself had championed in his business and television careers. Transactional leadership is the use of rewards and punishments to encourage highly valued behaviours, particularly loyalty. It is by definition more attuned to ascription than to achievement in the sense that maintaining the affiliations and status of those in a relationship matter almost to the exclusion of achieving some wider goal. Thus, negotiating over some common protocols for managing the pandemic took a back seat to rewarding the president’s overt supporters in the states and punishing his partisan enemies.

Bowling et al. (Citation2020, p. 515) present a series of examples of how this worked across the first seven months of the pandemic in 2020, quoting from a series of news articles to make the argument. States that ‘go too far’ in social distancing and stay-at-home rules were threatened with legal action by Attorney General Barr; governors calling on the federal government for help in acquiring medical equipment were admonished by Trump as follows: ‘The federal government is not supposed to be out there buying vast amounts of items and then shipping [them]’; Governor Larry Hogan of Maryland (a ‘disloyal Republican’) was chastised for ordering masks from South Korea because he ‘could have called [Vice-President] Mike Pence … I don’t think he needed to go to South Korea. He needed to get a little knowledge’; and Governor Andrew Cuomo of New York was instructed after asking for more ventilators (cue a scene in The Godfather where supplicants are kissing the ring of the padrone):

It’s a two-way street, they have to treat us well also. They can’t say, ‘Oh gee we should get this, we should get that.’ We’re doing a great job … they could have had 15 or 16,000, all they had to do was order them two years ago but they decided not to do it, they can’t blame us for that.

All this added up to a ‘chaotic’ type of transactional federalism (Bowling et al., Citation2020, p. 517). In this context, any pretence of planning disappeared in a miasma of complaint, resentment and lack of focus on the matter at hand. Systematic coordination between the federal government and the states as a whole was non-existent. Trump’s transactional and populist impulses then substituted in the absence of any system for coordination in producing the outcomes we have all seen. As federal experts cautioned early on that such minimal measures as distancing and masking were prudent actions to limit viral spread, transactional federalism locked into punishing states that pursued such strategies and rewarding states that ploughed on, out of fealty to the leader, in pretending for many months that the risks attached to the spread of the virus were no different from the annual flu outbreaks. ‘Prudence’ was not in Trump’s vocabulary. The conclusion to Bowling et al. (Citation2020, p. 517) is worth quoting to make clear the costs of this ‘gap filling’ approach to federalism:

Crises understandably place great stress on systems; when the system itself is chaotic, it is almost a foregone conclusion that the response of that system will be suboptimal. In addition, when states are forced into competition or when the federal government fails to act on issues with known externality concerns, coordination becomes nonexistent and, in this case, produces inefficiencies and the lack of provision of public goods that are evident today.

LOOK A LITTLE ON THE BRIGHT SIDE?

After this relatively poor overall performance, it is difficult to look on the bright side. But the actual experience of the 2020–22 pandemic may well encourage a rethinking and reworking of the current US federal system. The balance could shift back. All but the most ideological followers of Trump can see that the transactional federalism he proffered did little or nothing to compensate for the practical weaknesses of a dualist federal system mismatched to the problems of the 21st century. The fact that Trump’s federal government did manage to procure and manufacture vaccines that would have been beyond the capacity of any specific state might even persuade a few of his followers that the federal government does in fact have its domestic uses within the United States. That said, the extreme polarization of US electoral politics is now the major barrier. The Republican Party, ensconced in power now at the state level in many more states than the Democrats, and with significant advantages in senatorial and presidential elections, is now profoundly anti-federalist in the sense of pro-states’ rights and against the federal government doing much of anything except in national defence. Its populist war with government is specifically directed at the federal level, but is based in an overall hostility to the very idea of collective action for the common good (Fried & Harris, Citation2021; Mason, Citation2018).

As survey data from the United States and Australia suggest, a lack of commitment to collective action based on expert knowledge is now the biggest blockage in preventing a swing back to a more polyphonic federalism in the United States (Jackman et al., Citation2020). In this regard, responses to a question about trust in medical experts (a surrogate for attitudes towards experts and bureaucrats more generally) shows that US opinion on average is not that different from that in Australia, but the Trump supporters in the United States are the big exception. Across a range of policy areas and popular attitudes, including that of disdaining experts associated with the federal government such as the top US federal infectious disease expert Dr Tony Fauci and the CDC, such voters are likely to be openly opposed to a more involved and collaborative federalism (Durkee, Citation2022). State-level partisanship based largely in hostility to the US federal government is the current major bulwark of US dualist federalism (Birkland et al., Citation2021; Kincaid & Leckrone, Citation2022).

In conclusion, federal systems in general have not had a good pandemic, so to speak (e.g., ). That much seems clear. But neither have many putatively unitary states (e.g., Sharma, Citation2022). There was no simple magic such as that initially widely believed about authoritarian zero-covid solutions such as that mandated in China. That would have never been implementable in the United States. Centralization is not in itself a solution to managing pandemics, even if the United States could have done with much better integrated and coherent federal–state relations (e.g., Bourne, Citation2021). China’s highly centralized response seems to have built up a number of serious middle-term problems, not least the need to lockdown significant economic sectors, when in fact suppression to this extent has turned out to be less effective than milder mitigation plus mass vaccination in putting countries on the path to normalcy (e.g., Bloomberg, Citation2022; Emanuel & Osterholm, Citation2022; Qin & Chien, Citation2022; White & Olcott, Citation2022).

For its part, however, the United States could have done much better than it did, notwithstanding all its social–spatial inequalities. The geographical course of the pandemic illustrates not just systematic differences in demographic and health-related characteristics, but more strongly () the impacts of different state policies and the failures of both federal and state-to-state learning and coordination in reducing the impact of what would regardless have been a devastating crisis. Was this just a one-off misfortune or something indicative of deeper societal and institutional flaws (Bufacchi, Citation2021)? What then will be learned from this experience? One can hope, if somewhat forlornly, that a return to business as usual will not be the lesson (e.g., Brownson et al., Citation2020; Chyba et al., Citation2021). A revitalized cross-linking in public health and economic development policies across the states could capture both the benefits in many respects of centralization and the positive effects of local knowledge and values of decentralization. The dynamic is currently wildly out of balance, as the outcomes of the pandemic have shown. Coordination and collaboration collapsed. We have seen the result.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The original version of this paper was given as a presentation to the RSA Festival on Regions in Recovery on 18 June 2021. I have revised it in numerous respects to account for changes in the nature of the pandemic since the original version was written in May 2021. I thank Felicity Nussbaum, Scott Stephenson, Matt Zebrowski and two reviewers for helpful comments and suggestions that improved this article.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

REFERENCES

- Abbasi, J. (2021, March 24). How the US failed to prioritize SARS-CoV-2 variant surveillance. Journal of the American Medical Association, 325(14), 1380–1382. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.3368.

- Abedi, V., Olulana, O., Avula, V., Chaudhary, D., Khan, A., Shahjouei, S., Li, J., & Zand, R. (2021). Racial, economic, and health inequality and COVID-19 infection in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(3), 732–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00833-4

- Achenbach, J. (2022, February 15). US ‘excess deaths’ during pandemic pass 1 million. Covid killed most but other diseases added to toll, CDC says, Washington Post.

- Adolph, C., Amano, K., Bang-Jensen, B., Fullman, N., Magistro, B., Reinke, G., Castellano, R., Erickson, M., & Wilkerson, J. (2021, October 1). The pandemic policy u-turn: Partisanship, public health, and race in decisions to ease COVID-19 social distancing policies in the United States. Perspectives on Politics, first view.

- Agamben, G. (2021). Where are We Now? The Epidemic as politics. Rowman and Littlefield.

- Agnew, J. (2002). The limits of federalism in transnational democracy: Beyond the hegemony of the US model. In J. Anderson (Ed.), Transnational democracy: Political spaces and border crossings (pp. 56–72). Routledge.

- Agnew, J. (2021). Anti-federalist federalism: American ‘populism’ and the spatial contradictions of US government in the time of Covid-19. Geographical Review, 111(4), 510–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/00167428.2021.1884982

- Allain-Dupree, D., Chatry, I., Dougherty, S., Vammalle, C. (2020, May). Minimising the health, social and economic impact of the Covid-19 crisis: coordination across levels of government is key. OECD Forum Network.

- Avila, Y., Harvey, B., Lee, J. C., & Shaver, J. W. (2021, September 20). See mask mandates and guidance for schools in each state. The New York Times.

- Baker, M., & Ivory, D. (2021, October 18). Threats, resignations and 100 new laws: why public health is in crisis. The New York Times.

- Baldwin, P. (2021). Fighting the first wave: Why the Coronavirus was tackled so differently across the globe. Cambridge University Press.

- Beason, T. (2020, May 20). As all 50 states start reopening, questions on coronavirus tracking data fuel concerns. Los Angeles Times.

- Becker, S. J., Taylor, J., & Sharfstein, J. M. (2021). Identifying and tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants – a challenge and an opportunity. New England Journal of Medicine, 385(5), 389–391. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2103859

- Beer, T. (2021, September 6). US surges past 40 million Covid infections – daily case count far higher than Labor Day weekend of 2020. Forbes.

- Birkland, T. A., Taylor, K., Crow, D. A., & DeLeo, R. (2021). Governing in a polarized era: Federalism and the response of US state and federal governments to the COVID-19 pandemic. Publius, 51(4), 650–672. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pjab024

- Bloomberg. (2022, January 23). Xi Jinping’s Covid defense gets weaker with every Omicron case. Bloomberg News.

- Bohrn, B. (2021). Federalism in crisis: US and German responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Bertelsmann Foundation.

- Bollyky, T. J., Hulland, E. N., Barber, R. M., Collins, J. K., Kiernan, S., Moses, M., Pigott, D. M., Reiner, Jr, R. C., Sorensen, R. J. D., Abbafati, C., Adolph, C., Allorant, A., Amlag, J. O., Aravkin, A. Y., Bang-Jensen, B., Carter, A., Castellano, R., Castro, E., Chakrabarti, S., … Dieleman, J. L. (2022, February 1). Pandemic preparedness and COVID-19: An exploratory analysis of infection and fatality rates, and contextual factors associated with preparedness in 177 countries, from Jan. 1 2020, to Sept 30, 2021. The Lancet, S0140-6736(22), 00172–00176, online first. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00172-6

- Bourne, R. (2021). The COVID-19 case for bigger government is weak. Cato Institute.

- Bowling, C. J., Fisk, J. M., & Morris, J. C. (2020). Seeking patterns in chaos: Transactional federalism in the Trump administration’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 512–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941686

- Brilliant, L. (2021, December 13). To fight the global Covid-19 pandemic, we need a global game plan. Wall Street Journal.

- Brown, D., & Latulippe, N. (2021). Pandemic federalism: The COVID-19 response in Canada, Australia, and the United States. St, Francis Xavier University, Brian Mulroney Institute of Government.

- Brownson, R. C., Burke, T. A., Colditz, G. A., & Samet, J. M. (2020). Reimagining public health in the aftermath of a pandemic. American Journal of Public Health, 110(11), 1605–1623. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305861

- Bufacchi, V. (2021). Everything must change: Philosophical Lessons from lockdown. Manchester University Press.

- Bulman-Pozen, J. (2014). Partisan federalism. Harvard Law Review, 127(4), 1077–1146.

- Bump, P. (2021, October 13). A third of Americans say close friends or family have died of Covid-19. Washington Post.

- Cameron, D. (2022). The relative performance of federal and non-federal countries during the pandemic. In R. Chattopadhyay, F. Knüpling, D. Chebenova, L. Whittington, & P. Gonzalez (Eds.), Federalism and the response to COVID-19: A Comparative analysis (pp. 262–76). Routledge.

- Cerny, P. G. (1989). Political entropy and American decline. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 18(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298890180010501

- Chappell, B. (2021, December 14). 800,000 Americans have died of COVID. Now the US braces for an Omicron-fueled spike. NPR.

- Chyba, C., Cassel, C. K., Graham, S. L., Holdren, J. P., Penhoet, E., Press, W. H., Savitz, M., & Varmus, H. (2021). Create a COVID-19 commission. Science, 374(6570), 932–935. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0029

- Cortez, M. (2021, September 12). Here’s what the next six months of the pandemic will bring. Bloomberg.

- Cox Downey, D., & Meyers, W. M. (2020). Federalism, intergovernmental relationships, and emergency response: A comparison of Australia and the United States. American Review of Public Administration, 50(6–7), 526–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074020941696

- Cuadros, D. F., Miller, F. D., Awad, S., Coule, P., & MacKinnon, N. J. (2022, February 10). Analysis of vaccination rates and new COVID-19 infections by US county, July–August 2021. Journal of the American Medical Association, 5(2), e2147915. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.47915

- Cyr, J., Bianchi, M., González, L., & Perini, A. (2021). Governing a pandemic: Assessing the role of collaboration in Latin American responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Politics in Latin America, 13(3), 290–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X211049250

- De Biase, P., & Dougherty, S. (2021, January). Federalism and public health decentralisation in the Time of COVID-19. OECD Working Papers on Fiscal Federalism. No. 33.

- Delaney, A. (2020). The politics of scale in the coordinated management and emergency response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Dialogues in Human Geography, 10(2), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620934922

- del Rio, C., Malani, P. N., & Omer, S. B. (2021, August 18). Confronting the Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2, summer 2021. Journal of the American Medical Association, 326(11), 1001–1002. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.14811

- Dinan, J. (2020). The institutionalization of state resistance to federal directives in the 21st century. The Forum, 18(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1515/for-2020-1001

- Durkee, A. (2022, February 15). Americans have even less trust in scientists now than pre-pandemic, poll finds – especially among Republicans. Forbes.

- Ellyatt, H. (2021, September 6). Covid vaccination rates have slumped in some parts of the world and experts are worried. CNBC.

- Emanuel, E. J. (2020). Which country has the world’s best health care? Public Affairs.

- Emanuel, E. J., & Osterholm, M. (2022, January 25). China’s zero-Covid policy is a pandemic waiting to happen. The New York Times.

- Esarey, J. (2021, October 4). The myth that democracies bungled the pandemic. The Atlantic.

- Evans, M. (2021, September 3). Hospitals swamped with Delta cases struggle to care for critical patients. Wall Street Journal.

- Fenna, A. (2022). Australian federalism and the COVID-19 crisis. In R. Chattopadhyay, F. Knüpling, D. Chebenova, L. Whittington, & P. Gonzalez (Eds.), Federalism and the response to COVID-19 (pp. 17–29). Routledge.

- Ferguson, N. (2021, April 30). How a more resilient America beat a midcentury pandemic. Wall Street Journal.

- Fernandes, B., Navin, M. C., Reiss, D. R., Omer, S. B., & Attwell, K. (2022). US state-level interventions related to COVID-19 vaccine mandates. Journal of the American Medical Association, 327(2), 178–179. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.22122

- Ford, M. R. (2020, August 14). How weaponizing federalism prevented a cohesive Coronavirus response. ASPA Blog.

- Freeman, J. (2022, February 15). Will the ‘mask rebellion’ fuel a Republican landslide? Wall Street Journal.

- Fried, A., & Harris, D. B. (2021). At war with government: How conservatives weaponized distrust from Goldwater to Trump. Columbia University Press.

- Gaskell, J., & Stoker, G. (2020). Centralized or decentralized: Which governance systems are having a ‘good’ pandemic? Democratic Theory, 7(2), 33–40. https://doi.org/10.3167/dt.2020.070205

- Gibson, J. L., & Nelson, M. J. (2021). Judging inequality: State Supreme courts and the inequality crisis. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Gold, M., & Shanahan, E. (2021, August 4). What we know about Cuomo’s nursing home scandal. The New York Times.

- Goldhill, O. (2021, September 21). ‘Delta has been brutal’: Covid-19 variant is decimating rural areas already reeling from the pandemic. STAT.

- Gonsalves, G. (2021). Herd immunity: Covid deaths devouring the South are no accident. The Nation, September 22.

- Gordon, S. H., Huberfeld, N., & Jones, D. K. (2020, May 8). What federalism means for the US response to Coronavirus disease 2019. Journal of the American Medical Association, 1(5), e200510. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0510

- Gostin, L. O., Halabi, S. F., & Klock, K. A. (2021, September 15). An international agreement on pandemic prevention and preparedness. Journal of the American Medical Association, 326(13), 1257–1258. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.16104

- Gottlieb, S. (2021). Uncontrolled spread: Why COVID-19 crushed Us and How We Can defeat the next pandemic. Harper.

- Greenhouse, L. (2022, January 17). What the Supreme Court vaccine case was really about. The New York Times.

- Griffin, S. M. (2020, April 22). American federalism, the Coronavirus pandemic, and the legacy of Hurricane Katrina. Constitution Net.

- Halperin, D. (2022, January 24). Omicron is spreading. Resistance is futile. Wall Street Journal.

- Haseltine, W. A. (2021). Variants! The shape-shifting challenge of COVID-19 vaccine evasion and reinfection. Access Health International.

- Hawkins, D., Timsit, A., Suliman, A., Pietsch, B., & Knowles, H. (2021, September 7). Idaho moves to start rationing medical care amid surge in Covid hospitalizations. Washington Post.

- Healy, J., Fausset, R., & Goodman, J. D. (2021, September 10). Biden’s sweeping vaccine mandates infuriate Republican governors. The New York Times.

- Henninger, D. (2022, February 2). End the Covid panic now. Wall Street Journal.

- Holcombe, C. (2021, September 16). 1 in every 500 US residents have died of Covid-19. CNN.

- Howard, P. K. (2021, January 6). From progressivism to paralysis. Yale Law Journal Forum.

- Ip, G. (2021, September 15). How the US nailed the economic response to Covid-19. Wall Street Journal.

- Islam, N., Lacey, B., Shabnam, S., Erzurumluoglu, A. M., Dambha-Miller, H., Chowell, G., Kawachi, I., & Marmot, M. (2021). Social inequality and the syndemic of chronic disease and COVID-19: County-level analysis in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75(6), 496–500. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215626

- Ivory, D.Sun, A., Queen, C. S., Dupre, B., White, K., Higgins, L., Reynolds, C., Ruderman, J., Norman, D. M., Wong, B. G., Pope, L., Craig, M., Sherman, R., De Jesus, Y., Turcotte, M., & Avila, Y. (2021, December 18). See where 12 million US employees are affected by government vaccine mandates. The New York Times.

- Jackman, S., Ratcliff, S., Carson, A., & Ruppanner, L. (2020). Fear, loathing and COVID-19: America and Australia compared. US Studies Center, University of Sydney.

- Jain, A., Ko, A., & Sonnenfeld, J. (2021, September 15). The South’s soaring Covid rates show why we need vaccine mandates so urgently. Fortune.

- Jha, P., Deshmukh, Y., Tumbe, C., Suraweera, W., Bhowmick, A., Sharma, S., Novosad, P., Fu, S. H., Newcombe, L., Gelband, H., & Brown, P. (2022, January 6). COVID mortality in India: National survey data and health facility deaths. Science, 375(6581), 667–671. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abm5154

- Kamp, J. (2022, January 25). Covid-19 deaths top 2,100 a day, highest in nearly a year. Wall Street Journal.

- Kaufman, J. S. (2021, September 12). Science alone can’t heal a sick society. The New York Times.

- Kettl, D. F. (2020). The divided states of America: Why federalism doesn’t work. Princeton University Press.

- Khazan, O. (2020, August 31). The most American Covid-19 failure yet: Contact tracing works almost everywhere else. Why not here? The Atlantic.

- Khullar, D. (2022, January 24). Omicron by the numbers. New Yorker, 8–9.

- Kincaid, J., & Leckrone, W. (2022). American federalism and Covid-19: Party trumps policy. In N. Steytler (Ed.), Comparative Federalism and Covid-19: Combating the pandemic (pp. 239–49). Routledge.

- Koons, C. (2021, July 20). More variants are coming and the US isn’t ready to track them. Bloomberg Businessweek.

- Kropp, S., & Schnabel, J. (2022). Germany’s response to COVID-19: Federal coordination and executive politics. In R. Chattopadhyay, F. Knüpling, D. Chebenova, L. Whittington, & P. Gonzalez (Eds.), Federalism and the response to COVID-19 (pp. 84–94). Routledge.

- Kupferschmidt, K. (2021, August 20). Evolving threat: New variants have changed the face of the pandemic. What will the virus do next? Science, 373(6557), 844–849. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.373.6557.844

- Lane, C. (2022, February 8). Let’s be honest about why the Covid death rate is so high in the US. Washington Post.

- Lasco, G. (2020). Medical populism and the COVID-19 pandemic. Global Public Health, 15(10), 1417–1429. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2020.1807581