ABSTRACT

Australian regional communities are changing. The combined impact of out-migration and ageing populations means that the capacity of regional communities to function as they traditionally have is challenged. In this context, volunteer effort remains a vital part of building community resilience and social capital. Yet, volunteering per se is under threat, and encouraging young people to volunteer an even greater challenge. This paper presents the results of a project that sought to understand the barriers to, and incentives for, youth volunteering at three regional local government areas in South Australia. First, we find that despite a popular conviction that youth volunteering is on the decline, it has in fact increased; the actual decline is with those volunteers who are within the 35–55-year age groups. Second, we found that two models of volunteering exist in the regions: (1) volunteering as an activity involving participation on committees or doing regular primarily public good group-based work (e.g., emergency services, Rotary, conservation); and (2) event-based, one-off, fun activities (sometimes, but not always, for the broader public good). Volunteering per se, however, was considered by all participants as central to community identity. Culture, sports and youth clubs emerged as important hubs for youth activity and potential volunteer recruitment. We suggest a new model for regional youth volunteering that prioritizes events, partnerships and social media, as well as using existing institutions as bridging organizations.

INTRODUCTION

Regions across the world are increasingly subject to the pressures of ageing populations and out-migration to cities (often by the young). These two factors are impacting the resilience and cultural identity of rural communities. In Australia, the ability for communities to continue to function effectively due to these factors is brought into focus by the experience of volunteers. Volunteers underpin many essential services, including emergency services, healthcare and aged care, yet regional centres are experiencing a shortage of volunteers (Wilson et al., Citation2017). Regional societies within Australia have a strong volunteering culture, offering essential services to rural communities (Davies et al., Citation2021). This is because rural Australian communities see active engagement in volunteering activities as a vital way to contribute to their community (Duarte Alonso & Nyanjom, Citation2016).

In Australia, about one-quarter of people live in what are colloquially referred to as regional areas, but these regions are in fact a mix of peri-urban, regional cities and rural areas. Therefore, they can effectively be classified as non-metropolitan areas.Footnote1 Normally, these populations remain stable due to the in-migration of older adults and out-migration of the younger population (Collits, Citation2012). However, in non-metropolitan South Australia, where our three case studies local government areas (LGAs) are located, this balance is disrupted, with more and more people moving out (Bourne et al., Citation2020), resulting in declining populations (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2006c, Citation2016a, Citation2016b, Citation2016c, Citation2016d). To counteract the effect of this trend, such communities will need to become more resilient.

Given this context, engaging people – particularly youth – in volunteering is vital not only for invigorating regional economies but also for fostering community resilience. Community resilience is described as the capacity of a community to deal with uncertain environments (Berkes & Ross, Citation2013).

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE: THE CASE FOR PROMOTING (YOUTH) VOLUNTEERING

While there is no universal definition of volunteering, the notion of giving time for free to contribute to a project – often public good – as part of a community is common. Wilson (Citation2000, p. 2015) defines volunteering as ‘any activity in which time is given freely to benefit another person, group, or organization’, while the International Labour Organisation (ILO) (Citation2011, p. 13) refers to voluntary work as ‘unpaid non-compulsory work; that is, time individuals give without pay to activities performed either through an organization or directly for others outside their own household’. Volunteering Australia (Citation2015) states ‘volunteering is time willingly given for the common good and without financial gain’. As such, volunteering tends to be a proactive rather than reactive action that has positive outcomes for both volunteers and local communities (Wilson, Citation2000).

While volunteerism can boost resilience in non-metropolitan communities, it also provides numerous services and other benefits otherwise non-existent or disappearing. This is not just a normative assumption, based on a view that volunteering is inherently ‘good’, but is grounded in evidence from numerous studies that highlight that volunteering in Australia provides multiple benefits from a large number of perspectives (Warburton, Citation2010) and also services that would otherwise be up to the government. A decline in volunteerism thus means a decline in services for regional communities.

Such a decline, furthermore, is not insignificant. For this study, we used a formula to estimate the value of volunteering in the three case studies regions we investigated. We found that at the last census (2016) volunteers in the three regions generated a total value for the year of A$10,606,343 1997-dollars (equivalent today to nearly A$18.5).Footnote2 In other words, volunteering generated objective, tangible, economic value to its communities, providing services otherwise falling on government budgets (Davies et al., Citation2021; Warburton, Citation2010).

Volunteerism also builds employability skills in youth, and heightens self-esteem, communication skills and teamwork capabilities (The National Youth Agency, Citation2007). Volunteerism is also correlated to prosocial behaviour in children, further reinforcing the notion that volunteering indeed serves a purpose (Stukas et al., Citation2016).

Scholarship also asserts a correlation between social capital, defined here as social networks that bring together people from different backgrounds (Putnam, Citation2000) and volunteerism (Davis-Smith et al., Citation2002; Kay & Bradbury, Citation2009), illustrated by Putnam’s (Citation2000) study of one-off events and how they foster social capital. Stukas et al. (Citation2005) also demonstrate a correlation between volunteering and the creation of social capital, creating a feedback loop (Brady et al., Citation1999, cited in Stukas et al., Citation2005), where volunteerism builds social capital (Stukas & Dunlap, Citation2002) and equally social capital promotes volunteering (Portes, Citation1998).

Strong networks that reflect strong social capital will result in communities that thrive: it follows they will thus be more resilient, especially in dealing with the current (de)population pressures they are facing (Aldrich & Meyer, Citation2015; Chenoweth & Stehlik, Citation2001). From a more ‘everyday’ perspective, social capital has the potential to strengthen civil engagement in communities (Benton, Citation2016; Wilson et al., Citation2020), an outcome hardly negative for a community.

Volunteering can also foster the development of useful connections among the volunteers (Isham et al., Citation2006; Kay & Bradbury, Citation2009; Wilson et al., Citation2020) and leadership (Davies et al., Citation2021), making their services particularly needed.

Of course, volunteerism is not a panacea free from issues; as this paper illustrates throughout, class-based barriers exist, as well as ethnic, age related and linguistic ones.

Tonts (Citation2005), for example, provides an excellent exemplification of the challenges that can come with (sports) volunteering, defining sport ‘an important arena for the creation and maintenance of social capital’ (p. 137). With a focus on sporting clubs, this study cautions against excessive ‘romantici[zation]’ of volunteer roles. As cited by Tonts (Citation2005) and other studies (Whittaker & Banwell, Citation2002; Wild, Citation1974), regional Australian sports clubs are markedly divided by status, class and even ethnicity (Whittaker & Banwell, Citation2002).

The ‘politics of representation’ – as much as participation – within volunteering is thus of central concern to any emerging model of volunteering for it to be successful.

Some studies also identify youth-focused class-based barriers within volunteering regimes (Dean, Citation2016), with working-class youth often feeling intimidated about the social interactions that occur in these forums creating self-reinforcing patterns of exclusion. As cited by Dean (Citation2016), Lareau (Citation2000) instead notes that sometimes it is the parents of working-class children who feel this exclusion and hence prevent their children from participating.

There are also ethnic-based barriers to volunteering (Kerr et al., Citation2001) that impede the involvement of people of non-English speaking background, as well as Indigenous people. These barriers can assume systemic proportions. Ageism, as well as ‘disrespect’, also prevents young people from joining existing volunteering organizations (Walsh & Black, Citation2015), which reflects yet another glass ceiling that hovers over volunteering activities.

Moreover, volunteerism does not benefit everyone equally. Wilson (Citation2000), for example, found that participation in volunteering was constrained by income levels, as well as parental and marital status, and the type of occupation. Full-time workers, for instance, tend to volunteer less than part-time employees (Wilson, Citation2000), or parents with school-age children may volunteer more than parents with very young children (Einolf et al., Citation2011).

These dimensions, while they merit attention, do not ontologically compromise the otherwise positive role volunteerism plays in communities nor do they cancel the benefits volunteering produces.

MOTIVATION AND VOLUNTEERING

People volunteer for a number of social, cultural and psychological reasons (Duarte Alonso & Nyanjom, Citation2016; Einolf et al., Citation2011; Hustinx et al., Citation2010; Wilson & Musick, Citation1997). Beyond collective outcomes, volunteering offers personal benefits (Lough et al., Citation2018) and, in regions, offer opportunities for social interactions particularly older people (Isham et al., Citation2006). Altruism is also a driving factor as is religion as a motivator for volunteering (Butrica et al., Citation2009; Okun et al., Citation2015; Wilson & Musick, Citation1997). A range of psychological and social rewards also motivate people to volunteer (Clary et al., Citation1998; Koss & Kingsley, Citation2010; Omoto & Snyder, Citation1995; Stukas et al., Citation2016). More specifically, factors such as learning opportunities, self-development, networking and career enhancement prompt individuals to volunteer (Clary et al., Citation1998; Mellor et al., Citation2009).

Young individuals also volunteer, although what motivates them to do so differs (Omoto et al., Citation2000). Younger volunteers are largely motivated by the types of relationship they may develop, and meeting/making new friends (Haski-Leventhal et al., Citation2008; Omoto et al., Citation2000), while older volunteers were inspired by service and societal obligations concerns. Strong connections with family, friends, religious groups and schools also facilitate young people to volunteer (Duke et al., Citation2009; Perks & Konecny, Citation2015). In South Wales, for example, Muddiman et al. (Citation2019) demonstrate that young people who have positive relationships with their parents and grandparents are more likely to be involved in ‘activities to help other people or the environment’. Beyond the family, schools are key organizations that foster volunteering (Walsh & Black, Citation2015).

An important consideration in regional communities pertains to the fact that structural barriers may lead to lower participation of youth in volunteering, as socio-economic disparities/disadvantages are a structural deterrent to volunteering (Gage & Thapa, Citation2012; Marzana et al., Citation2012; Walsh & Black, Citation2015). The cost of volunteering for youth with low socio-economic status in these cases is not offset by the benefits: loss of potential income, lack of money, time and access to transport are all barriers preventing such young people from participating in volunteer programmes (Davies, Citation2018; Walsh & Black, Citation2015). Conversely, volunteer groups are likely to be overrepresented by the affluent members of the community (Haski-Leventhal et al., Citation2010).

The structure and culture of the organizations that facilitate volunteering (overregulation of the voluntary sector and its associated formalities, e.g., public liability insurance, permissions, and police checks) can act as another barrier (Davies, Citation2018; Hankinson et al., Citation2005) (Brueckner et al., Citation2017; Moffatt, Citation2011). Ageism, discrimination and disrespect also prevent young people from joining in volunteering (Walsh & Black, Citation2015). Young volunteers may also be typified as ‘unreliable’ because they do not always want to commit to long-term engagements (Moffatt, Citation2011). Young people, in turn, may find that volunteering organizations are not welcoming. Another barrier is the lack of ‘voice’, or spaces made for young volunteers to be heard or for their own aspirations to be included (Holdsworth, Citation2007).

This suggests that there exists a disconnect between the way volunteering is conceptualized in programmes and how young people view such programmes, indicating a need to heighten the appeal of volunteering and bring fresh perspectives to volunteering programmes (Kragt & Holtrop, Citation2019; Walsh & Black, Citation2015). Wilson et al. (Citation2017, Citation2020), Davies et al. (Citation2021) and Duarte Alonso and Nyanjom (Citation2016), to name a few, have identified that there is a need to understand volunteer motivation, the future of volunteers, retention and recruitment strategies for volunteers, and what are the individual needs of younger and older volunteers (Macduff et al., Citation2009; Wilson et al., Citation2017).

These studies provide an important baseline for understanding what motivates young people to volunteer, but there is a need to further investigate the factors that influence young adults to engage in volunteering in regional Australia. The present study contributes to that knowledge gap by exploring the factors that inhibit and incentivise youth volunteering in regional South Australia.

In this context, our research sought to answer the following research questions:

• What motivates youth volunteering in the region?

• What barriers exist to prevent youth from volunteering?

• What future opportunities exist to enhance the recruitment, retention, and motivation of volunteers?

Youth here is understood as any individual between 15 and 24 years of age, and in our survey we broke this up again into ‘school age’ youth, between 15 and 19, and ‘older’ youth, between 20 and 24.

METHODOLOGY

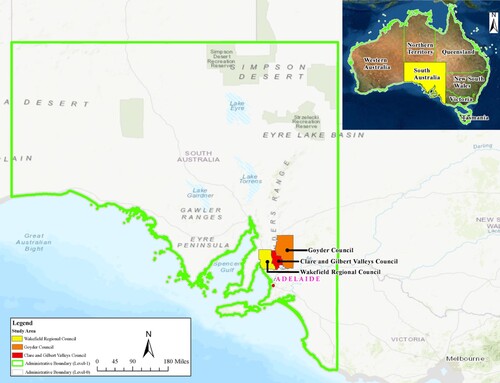

To answer these questions, we adopted a case study approach underpinned by mixed methods for data collection and analysis. The use of case studies was appropriate in this context as it facilitates in-depth, multifaceted understanding of a complex issue in its real-life context (Yin, Citation1981). Specifically, we focused on three regional local councils: the Clare and Gilbert Valleys, Wakefield, and Goyder ().

These local governments fall within the interests of the local government alliance group, Legatus. The Legatus Group is a peak local government organization that seeks to assist 15 local governments within its boundaries. Legatus liaises with local governments to build programmes that support social, economic and environmental sustainability, but do so in ways that build social coherence and networks between councils. These regional areas, located approximately 100 km north of Adelaide, the capital of South Australia (), were selected for this study, as they were identified as being the most in ‘decline’ – understood to be significant and chronic – and a decline that is both perceived and actual.

Table 1. Case study descriptions.

Empirically, workers, especially skilled, in regional communities are on the decline. Davies (Citation2008), for example, finds that a decline in in-migration of younger generations has effectively resulted in a reduction in the capacity of rural communities to replenish their skill base. This is particularly significant in South Australia (alongside Western Australia and the Northern Territory), where it has been estimated that between 2011 and 2016, communities lost one resident every five due to out-migration (Bourne et al., Citation2020). Our three case study regions are no exception; in terms of ageing populations, between 2006 and 2016 (ABS, Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2006c, Citation2016b, Citation2016c, Citation2016d), all regions witnessed the median age rising, with two (Clare and Gilbert Valleys and Goyder) of the three regions at the time of the last census older by 10 or more years than the Australian median. Unemployment is on the rise too, with all case study regions recording a growth in unemployment rates. This is constituted by a growth between 4% and 6% across the three regions in part-time employment, coupled with a decline in all regions of full-time employment (ABS, Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2006c, Citation2016b, Citation2016c, Citation2016d), indicating an increasing casualization of the workforce. In 2006, these regions used to have either a higher or an almost equal unemployment rate to the rest of Australia, but in 2016 all three regions recorded a higher unemployment incidence relative to the nation.

The case study regions thus are all ones that are experiencing youth out-migration, economic decline and have ageing populations.

At a perceptual level, this declinist narrative is reflected by an almost unanimous community view that there are fewer economic opportunities in the regions – at least for the youth and demographically fewer young people (and even less who were prepared to volunteer).

Methodologically, we sought to determine both perceptual and empirical factors that drive and potentially inhibit youth to volunteer in the three case study regions analysed.

To undertake the research within these case study regions, we adopted a mixed-method approach, based on semi-structured qualitative interviews, surveys and documentary analysis. We based our work on the accepted definition by Creswell (Citation2007, p. 2) as follows: ‘Mixed Methods Research is research in which the investigator collects and analyses data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or program of inquiry.’

This approach was used because it enabled us to obtain a diverse and richer range of data. The use of multiple methods and sources of data also enabled us to expand the evidence base and triangulate; hence, the verification/corroboration of our results. Such a design also enabled us to examine the research question from a number of perspectives (Regnault et al., Citation2018). We undertook the project between September 2019 and March 2020. Given the focus on specific case study regions, the use of a mixed-method approach enabled us to identify a broad review of views across the three councils, and then gather some in-depth insights from both younger and older volunteers. This approach was appropriate because it enabled us to find more youth to talk to because in the initial project stages it was very difficult to find and access young volunteers.

Data collection

Over a period of seven months from September 2019 to March 2020, we gathered information in three ways: (1) conducted documentary analysis, which included analysis of census data from the ABS to create baseline profiles and a review of literature to understand of the issue; (2) undertook 30 semi-structured interviews across key organizations and people in the three regions; and (3) implemented two online surveys (using Survey Monkey platform), one for youth (36 responses) and another more general one on youth volunteering (48 responses). Among the youths who participated in the survey, 95% were involved in diverse volunteering activities and about 50% of them volunteered once in a week. The youth survey sought to gather data about what types of volunteer work young people are involved in in the region, and what motivates and demotivates them to volunteer. The general survey, on the other hand, was designed to collect data from adults involved in volunteering, as well as managing volunteer organizations and groups. Together, the surveys produced information on what opportunities and challenges exist to engage youth in volunteer activities.

Interviewees were selected via a set of criteria which were: (1) participants were active volunteers in some capacity or worked with volunteers; (2) resided in the region; and (3) (for the youth) were between 18 and 24 years of age. Interviewees were asked to describe their background (i.e., age, family background regarding volunteering, profession/employment status, etc.) and then describe their experience as volunteers, and observation of volunteering in their communities. We also asked for a description of the organization/group they volunteered for. Key questions included the following:

• How many volunteers worked in their volunteering group?

• What is the age range/average age of volunteers?

• How many volunteers were 24 years or younger in their volunteering group?

• What are the challenges facing volunteering groups?

The interviewees were also asked to express their general concerns in relation to their communities, including their opinion on who are the top volunteering groups in their area and how many young people volunteered in the region. We asked how people felt about their concerns for and opinions on volunteering: what they believed motivated and what discouraged volunteers, especially the youth. We also explored how the motivations of young volunteers differ from the motivations of older generations. Given that virtually all volunteers claimed that young people do not volunteer as much as other age groups, we wanted to know what factors they believed would motivate young people to volunteer.

Data analysis

Most of the data collected through questionnaires were in close-ended format. The survey data were processed and analysed using SurveyMonkey platform and Excel, while data gathered through qualitative interviews were coded and analysed using thematic analysis. The use of thematic analysis permitted us to identify patterns and meaning across a data set to provide answers to the questions being investigated (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). Thematic analysis is a flexible method that can be used across methodologies and questions because it assists in documenting perceptions, feelings, values and experiences. We took an inductive approach to the analysis in that we let the coding and theme development be indicated by the data, rather than assume anything before beginning. We conducted the analysis in five stages: (1) familiarization with the data; (2) searching for themes; (3) coding; (4) reviewing and amending themes; and (5) writing up.

Data collection continued until the research reached ‘information saturation’. This is the point at which no new data reveal themselves, and the researcher can conclude that the research has achieved its goals (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). Throughout our analysis we also applied the criteria for establishing trustworthiness in qualitive research (Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985). These criteria are as follows: (1) credibility – confidence in the ‘truth’ of the findings; (2) transferability – showing that the findings have applicability in other contexts; (3) dependability – showing that the findings are consistent and could be repeated; and (4) confirmability – a degree of neutrality or the extent to which the findings of a study are shaped by the respondents and not researcher bias, motivation or interest.

Triangulation was used to corroborate our key findings. This technique is used within social sciences to guarantee validation of data by verifying them across multiple sources, which creates greater confidence in the final results (Denzin, Citation2017). In this study, we achieved triangulation by including three investigator perspectives when completing the thematic analysis of the semi-structured interviews and the survey and by using multiple data sources (transcripts, survey, literature and ABS statistics).

RESULTS

Confusion surrounding youth volunteering

While participants all thought that volunteering was a really important part of a community, we found that their views in relation to youth volunteering did not correlate when mapped against census data. It is not clear why this was the case. We assume it is the effect of anecdotal ‘lore’, but this dissonance has consequences as it meant there was no perceived urgency to develop an active strategy to encourage youth volunteering.

For example, participants believed that youth volunteering was decreasing – and, further, that a crucial task facing regional communities – is to advance ways in which youth could be incentivised to do more. All the interviewees reported there were very few young volunteers in their LGAs. The extent of this perceived ‘scarcity’ was also fairly similar across the regions: an interviewee from Burra (Goyder) estimated the number of young (≤ 24 years old) to be ‘less than 1%’, whilst another volunteer from the Clare and Gilbert Valleys LGA claimed to know no young volunteers (although she said young people are drawn to sports clubs). In Wakefield, two interviewees gave similar responses. Of those who knew of young volunteers, the numbers were also calculated to be very small, the largest being three.

However, analysis of census data finds that while the numbers of young people volunteering is indeed small, over the last decade the proportion of youth volunteering per se has not in fact declined, but increased. Youth volunteering as a percentage of the population by relative age group by LGA and contrasted volunteering participation per capita (by age group between 2006 and 2016), has in fact grown significantly across all three regions (ABS, Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2006c, Citation2016b, Citation2016c, Citation2016d). In WRC the percentage of people aged 15–19 volunteering per capita has grown by 25.2% (the second highest growth rate per capita in the region, after those aged 20–24), 13.7% in Goyder and 28.8% in the Clare and Gilbert Valleys. The percentage of those aged 20–24 volunteering per capita has also grown by 52.6% in WRC (the highest growth rate per capita in the region), 26% in Goyder and 21.7% in the Clare and Gilbert Valleys. On the other hand, volunteering overall per capita has decreased across all the regions, on average, for not only those aged 35–55 (as reflected by nominal values), but a larger age group comprising those aged 25–69.

Another key assumption within the project was also upended: it was asserted by respondents that out-migration of youth is negatively affecting local economies. However, our analysis shows that the main issue is not in fact the scarcity of young volunteers, but rather the fact that the ageing senior volunteers were not being substituted by the ‘new’ seniors. As one long-term volunteer of the Clare Rotary Club explained, in the 1970s the club used to have around 450 members – a number which was already back then shrinking at a rate of 10% per year: today, the Rotary Club has no more than 21 members. Further, statistical analysis of census data showed that in fact the real dearth in volunteering activity occurs in the demographic in those between 35 and 54 years. Financial assessments of the economic value of volunteers to communities (conducted in line with other Australian studies: Haukka et al., Citation2009; Trewin, Citation2000) also identifies this loss of older volunteers as a major problem, especially as their voluntary work every year, per volunteer, can be up to twice as valuable as the work of the average young volunteer. Thus overall, we find, that despite the popularly held community discourse that links a lack of youth volunteering to negative economic impact, it is not substantiated by statistical evidence.

Models of volunteer engagement matter for youth

Another key idea – what constitutes volunteering per se – was articulated by our results. Analysis revealed an articulation of two models of volunteering, which we present as a finding, because they were not a precursor for our investigation. These models are instructive because what may be understood and defined by government and others in specific operational ways as volunteering is not necessarily how people in the actual community doing the volunteering may approach or construe it. The articulation of how volunteering is really modelled and practiced in our case studies is instructive because it enabled us to gather insights about what is working and what is not, and to suggest a new model.

One model constructs volunteering as an activity that involves participation on committees or doing regular primarily public good group-based work (e.g., emergency services, Rotary, conservation). The other model envisioned volunteering as event-based, one-off, fun activities (sometimes but not always for public good) that require volunteer (as in unpaid) effort to expedite. The former model is a familiar and conventional one, largely implemented by older volunteers, and based on a construction of volunteering as ‘public good’ work. This type of volunteering asks volunteers to attend regular (often monthly, sometimes fortnightly) committee meetings, and then to undertake activities outside of meetings, largely on the weekends. Many volunteers in this model held ‘official’ committee or other positions and had committed to a particular group (or groups) for many years. Attachment to particular groups to volunteer for corresponded to individual interest – this may be conservation, elder care, disability services, and community or sport activities.

The second model was one generated and described by our youth participants as their preference. They asserted a view that volunteering is more than ‘work they do that they don’t get paid for’, but that it should also be fun and exciting. It did not necessarily have to involve a public good component, although many events discussed were in fact related to public good, including fund raising activities for victims of various disasters or to help our particular sectors (i.e., disability). Volunteering as such was not perceived to require regular activity, nor loyalty to just one institution – diversity was valued. This other model was predisposed towards the use of social media and online communication as a modus operandi, where volunteer commitment was variable: one week/event volunteering could be for emergency services, but another time to raise funds to support a vulnerable individual.

Motivations for youth volunteering compared with older generations

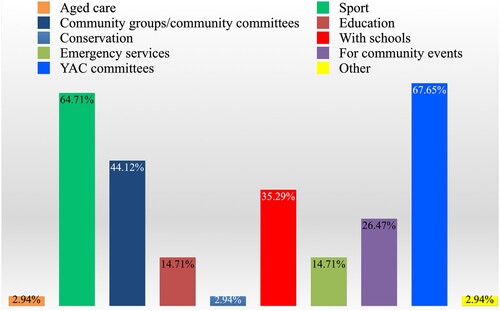

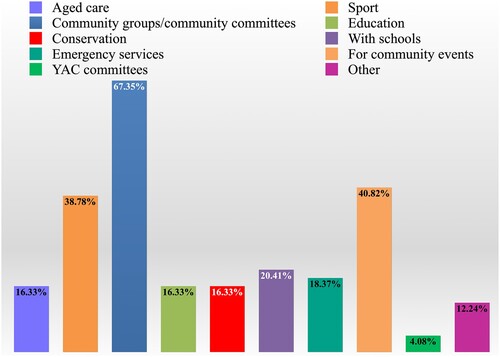

Given the differences between the models of volunteering per se, it is not surprising that there are also differences between how, why, and what motivates older and young people to volunteer. For example, as shown in and , the places that young people volunteer for are not the same as where older people volunteer.

When we asked youth about how and where they volunteer, youth identified sport, community groups and the youth advisory committee (YAC) as the core way they volunteer (). Some did volunteer work at school, and some did participate in community events and emergency services every now and then. Very few identified conservation or aged care as a focus for their volunteering activity. Most typically understood their weekly volunteer activity as being via attendance at weekly sports practice sessions.

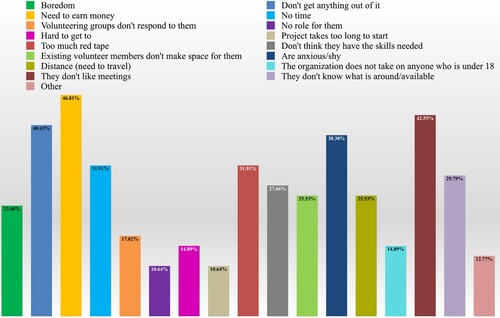

Many reasons were nominated by older volunteers for why young people did not choose to volunteer in other ways, but chief amongst them was the perception that they needed to earn money and, therefore, had less time to involve in volunteering. Another clutch of reasons suggests that red tape, meeting governance and lack of clear roles for them inhibited many young people. Finally, it was perceived many young people did not know what volunteering was, what opportunities existed and how to go about entering the volunteering community. Overall, as highlights, the sheer diversity of these answers and their relative, even spread suggests some confusion about, and lack of understanding by, older volunteers about what actually motivates young people to volunteer.

Community feelings, family and local enabling institutions influence youths to volunteer

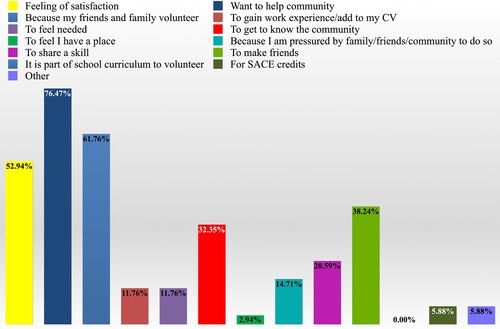

As shown in , when we asked young people what motivates them to volunteer, wanting to help the community was the key motivation, closely followed by it is what their friends and family do. Role modelling emerges as another key factor that motivates young people to volunteer.

Figure 5. General survey results showing the factors that motivate young people to get involved in volunteering.

Our study finds that for all participants, youth volunteering was perceived to have a number of intergenerational advantages, which, while unrelated to the aging local population, provide enduring benefits to communities. Interviewees, for example, consistently suggested that families and schools should be involved in promoting youth volunteering. Many volunteers also reported that their children, now adults, still volunteer because they ‘set the example’, or that they volunteer themselves because their parents used to. Others explained that children who they have seen growing up in schools where volunteering was part of the curriculum still volunteer today as adults. A married couple who volunteer (from Wakefield) also suggested that school-based volunteer initiatives (such as offering credits) are key volunteer hubs. This was a perspective shared by a volunteer of Clare’s State Emergency Service’s (SES) unit, who suggested the involvement of schools (also outside the curriculum), in volunteering would be useful, recommending, for example, bringing the kids to ‘see the trucks’. Another volunteer lamented the schools’ ‘lack of vision’ regarding volunteering – implying that, if they did more in this area, youth volunteerism would increase. Further, many volunteers reported their parents volunteered as well – mentioning this aspect to explain why they became volunteers themselves, reflecting a trend of intergenerational influence in youth decisions to volunteer. Another volunteer, from Wakefield, claimed (indicating their belief in the centrality of family in encouraging youth volunteerism) that volunteerism ‘it’s genetical [sic]’, explaining those coming from volunteering families volunteered too, unlike those coming from backgrounds who did not, concluding that, ‘You need parents to volunteer to have the youth volunteer.’

Youth volunteering is in fact correlated with volunteering later in adulthood (Brown et al., Citation2003; Moorfoot et al., Citation2015) and the promotion of youth into volunteering has long-term positive intergenerational impacts on volunteering in other age groups, as the current youth enters, later, into adulthood (Walsh & Black, Citation2015). Parental volunteering is also positively correlated with children’s volunteerism (Perks & Konecny, Citation2015). Furthermore, an American study found that ‘parents can induce formal volunteering by encouraging their teens to volunteer’ (Paintsil, Citation2019, p. 55), meaning that even if the parents are not volunteering themselves, they can still successfully promote volunteering in their children. Embodiment by the parents of a volunteering model has been also found to be correlated with prosocial behaviours in children (Stukas et al., Citation2016), indicating that long-term benefits accrue from domestic exposure to volunteering in early life. Information is critically important in the recruitment of more young volunteers, and schools can be at the frontline of facilitating this information flow. Many studies (Astin & Sax, Citation1998; Flanagan et al., Citation1998; Hart et al., Citation2007; Haski-Leventhal et al., Citation2008; Hill & den Dulk, Citation2013; Torres, Citation2003; Verba et al., Citation1995; Walsh & Black, Citation2015) emphasize that schools that promote social participation are positively correlated with youth volunteering. Schools also offer a further opportunity: volunteering is associated with better academic performance in children (Khajehpour & Ghazvini, Citation2011; Moorfoot et al., Citation2015; Wang & Fahey, Citation2011).

However, given the apparent lack of volunteerism in schools, as well as challenges in approaching schools, we were not able to further explore the role played by schools in regional youth volunteering. Over half of those interviewed for this project asserted the value of schools in encouraging volunteering in children, including through credit incentives via the South Australian Certificate of Education (SACE).

In addition to the emergence of schools as an important enabling institution for volunteering, the role of local institutions such as The Star Club (a peak sports institution) and the YACs also played an integral role in bringing together young people and encouraged them to volunteer.

Interestingly, most people we interviewed did not construct their own contributions to sports as a volunteering but more as a recreational activity. Yet such regional institutions can be used to increase trust and social cohesion especially after or during times of stress (Aldrich & Meyer, Citation2015). For example, the Star Club Program, and indeed any of the sports bodies that implement sports programmes in the region, effectively act as bridging institutions to facilitate all sorts of volunteering in practice, whether coaching, fund raising or running management committees, occupational health and safety, overseeing local governance, and reporting arrangements. These clubs are an important focal point for youth volunteer activities, especially within and across families/generations and across the region over 100 youths are involved in volunteering at a junior coaching or umpiring level with many more assisting their parents on a weekly basis across a wide range of sports.

YACs also emerged as key enabling institutions. There were two such committees within the case study area: the Goyder YAC and the Clare and Gilbert Valleys YAC. Both are attached to their local council and as stated on the Goyder Council website: ‘aim to give the young people of the region a means of communication with the Regional Council of Goyder and their Elected Members’. YACs also attempt to ensure that young people have a voice in council affairs and seek to promote a positive image of youth. YACs undertake a spectrum of activities, including raising awareness of local opportunities and activities, developing youth capacity via skills training, and development of youth events and programmes, raising the profile of youth in the regions. Again, this group facilitates various forms of volunteering, examples including committee members assisting in fund raisers, development of recreational areas, such as skate and swing parks, revitalization by art projects and ‘Big Day Out’ Events such as the Battle of the Bands Event held by the Goyder YAC in 2019.

Overall, our results indicate that groups such as YACs and the Star Club – as well as other institutions such as schools – could be used to strengthen volunteering and build social capital by acting as bridging institutions.

Increasing the presence of state governance and formalization discourage volunteering activity and sense of community

Increasing corporatization of volunteering is another key factor discouraging youth to volunteer. For example, volunteers now have to report how many hours they have worked, need to make ‘strategic plans’, draft legal documents (previously not needed) and cut ‘red tape’. We also found this factor was also a key disincentive to young volunteers, who were not interested in ‘getting bogged down in forms’ but wanted to make a more active and engaged contribution.

Loss of community autonomy and/or lack of voice was also identified by both younger and older volunteers as an issue relating to ensuring sustained engagement over time. For example, synthesis of the interviews reports a ‘shrinking’ of community capital and cohesiveness. A volunteer (over 75 years and based in Clare) of Clare Rotary Club reported that the average age of the club members grew from 45–55 to around 70 and that the number of Rotarians has shrunk since the 1970s. As he explained, historically community members used to be involved in many aspects of Clare life – aspects in which all the community was heavily involved in volunteering and was supported, and self-reinforced, by a strong sense of community ownership. He explained that in the 1960s, he and many other members of the Clare community built the local kindergarten – ‘it’s owned by the community, you got that ownership’ and ‘it’s not even volunteering, it’s caring’. He then lamented how this sense of ownership was ‘stripped away’ from him and other members of the community as the government took control of more activities and services within his community, and funding for local activities started to come from outside of the community (he notes before that there was ‘massive fundraising’). This meant they effectively lost the possibility of having any say on a number of local services, as one volunteer explained in relation to what had been extensive volunteering at the hospital: ‘Once the government took control of the hospital, it was impossible to know about it’ and that ‘governments don’t have a very good picture’, suggesting a loss of community autonomy over time to make key decisions in their local communities. This lost sense of ownership is attributed to the decrease of overall volunteering: people did not feel they had a role anymore and/or were able to contribute.

A fading sense of community was also reported by an interviewee in Port Pirie, who believed this was especially fading in young people; this was thought to have, in turn, decreased their volunteerism. One volunteer was so frustrated by having lost this sense of ownership of his community that he believed the solution was to ‘cut the money’ (i.e., reduce government funding). Thus, it would make the community reunite to contribute to it, restoring the sense of ownership and increasing volunteering. This shows a desire for people to ‘have their community and control of it back’. This view is supported other studies: Ainsworth (Citation2020, p. 6) found that ‘volunteering behaviour increases the sense of ownership users have over the non-profit’ and that this phenomenon is self-reinforcing, meaning ‘that sense of ownership has a positive role in fostering positive attitudes towards volunteering and repeat volunteering intentions’.

DISCUSSION

In summary, this study has demonstrated that there is a community belief that youth volunteering should be promoted and expanded, especially given the ageing population. Volunteering was unanimously constructed as being central to a community; it is intergenerational and builds community identity. It is a form of social capital that can create new partnerships brokered between bridging institutions at regional levels. The possibility of meeting its potential, however, tends to be inhibited by the ways volunteer organizations operate that often ‘have little connection to the aspirations and motivations of volunteers’ (Brueckner et al., Citation2017, p. 31), especially those who are young. This means formalized and professionalized approaches to manage volunteers are often preferred by middle- and older aged volunteers, but seem outdated to and do not attract young people.

These results point to the possibility of new directions in volunteer activity, which, in turn, can be used to build social capital and resilience within communities. We suggest that a model of volunteering – which is fun, event-based, social media driven and diverse in activity – is one way forward. This is a model that facilitates a range of activities that are broad in scope and not necessarily tied to one organization. Work by Misener and Mason (Citation2006) confirms this modus has potential. In relation to one-off sporting events, they found they provide ‘citizens with knowledge and a framework for further participation in community building’ (p. 44), and can contribute to build much needed (especially in regions) social capital. Such event-based, fun volunteering plays an enabling role into long(er)-term community participation: the skills and knowledge created remain in the community long after the event itself has occurred. In such contexts, youth indicated that they will not only attend, but willingly give up their time (often) to volunteer.

We suggest that volunteer institutions could be reconfigured to build on their inherent capacity to be bridging organizations. Bridging organizations are ‘formal organisations that use specific collaborative mechanisms … to bring together diverse actors’ (Kowalski & Jenkins, Citation2015, p. 1). They provide ‘an arena for knowledge co-production, trust building, sense making, learning, vertical and horizontal collaboration and conflict resolution’ (Berkes, Citation2009, p. 1695). In facilitating transactions between actors and groups, transaction costs are lowered as tasks are distributed and coordinated, whilst social learning facilitated. Volunteering also offers specific opportunities for social learning where it is a process of ‘iterative reflection that occurs when experiences and ideas are shared with others’ (Berkes, Citation2009, p. 1697).

As bridging organizations, volunteer institutions can also assist in sharing information and knowledge which can assist in better policy – this is a pivotal contribution given the current fragility of regional community development. In this context, we argue there is much scope for schools and groups like the Star Club and YACs to partner explicitly with other regional and local volunteer groups to build youth energy into volunteering and in turn social capital. In building social cohesion, the community in turn builds strength to oppose what Maru et al. (Citation2007) call the ‘agglomeration forces’ that currently drive out-migration. In this way, volunteering can play a role in building the norms that evolve from social interaction in and between small and large communities (Maru et al., Citation2007). Further, intergenerational connection and knowledge transmission will be consolidated via such partnerships. As such, volunteer institutions as bridging organizations also facilitate processes of bridging knowledge, where multiple knowledge systems – across generations and at varying scales – can be combined and assist in building the strength of regional communities (Reid et al., Citation2006). Finally, the deliberate commitment to building the role of volunteer groups as bridging organizations will also enable a move away from conventional forms of volunteering which demand regular attendances and loyalties to particular groups and causes, to a diversified portfolio of activities that are fertilized between multiple groups at multiple scales, offering young people multiple opportunities to participate when and where they can.

Regarding the role of schools as volunteering bridging organizations, a different but comparable study conducted in three US regional communities (Martin & Henry, Citation2012), schools promoted ‘agriculture programs’, which combined volunteering, education, and career opportunities. Such activities successfully contributed to the building of communities and their social capital, demonstrating the possibility that intergenerational community identity can be built via volunteering.

Second, in building towards intergenerational social and knowledge capital, greater youth involvement in volunteering will assist regional preparedness to deal with uncertainty (Leader-Elliott et al., Citation2008, p. 30) and will assist in community responsiveness such as to an emergency. For example, trained youth volunteers in the emergency services helps create community capacity development and facilitate complex community exchanges between community volunteers and a range of state actors; this is an important role, given volunteer organisations are often those ‘communicating at the edge of chaos’ (Duhé, Citation2007; cited in Chia, Citation2010).

How, what medium is used, and who communicates about issues of concern in regional communities are also important in ensuring ongoing community sustainability and social capital. Our results indicate the adoption of social media driven communications about activities will not only mobilize youth to participate but overall encourage forms of community engagement and networking with each other and between key bridging organizations. As Chia (Citation2011) observes of the potential of social media to impact how organizations and their communities understand each other, its adoption also has social justice benefits: ‘Grass roots involvement through social media such as Twitter, YouTube, and Facebook opened up opportunities to communicate with those who were marginalised and often excluded from face-to-face dialogue’ (p. 343). As early as 2001, social media, and more broadly the internet was already seen to be building ‘social capital by enhancing the effectiveness of community-level voluntary associations’ (Salahuddin et al., Citation2015, p. 944) and assist peoples to increase mutual support, social trust, sense of community, and access to resources (Ballew et al., Citation2015). Social media can also be used for recruitment, as well as reinforcement of existing structures. Moreover, the use of social media and user-generated content online platforms (such as Web 2.0) provide opportunities for social participation and engagement (Ballew et al., Citation2015): in a UK study (Sharp & Carter, Citation2020), social media, in the context of disaster management, tangibly supported both the recruitment of volunteers and the management of their activities, as well as providing greater fundraising opportunities to volunteering groups. This suggests (while not yet widespread in our case-study regions) that cyber-volunteering (increasingly emerging in Australia and internationally during the Covid-19 pandemic), might provide further opportunities for youth engagement in volunteering and refresh social capital – including as an emerging form of ‘online social capital’. In these cases, the use of digital volunteering could prove effective also in maintaining out-migrated youth within the communities, although further research over this last potential is needed.

While this paper reveals there is potential for new forms or models of volunteering, which may encourage youth to volunteer, we do not mean to suggest this should replace existing modes of volunteering. A range of pre-existing volunteer activity that requires a more consistent form of participation will always exist. Organizations that require such forms of volunteering will need to find ways to build youth participation. The results from this project suggest that organizations, which require ongoing volunteer activity, could still harness the power of social media, situate activities within social and familial networks, as well as facilitate social and ‘fun’ activities, encouraging youth to volunteer in more regular ways. Moreover, youth remain but one part of the cohorts that volunteer in any community. Other forms of regular volunteering can use different forms of social capital to strengthen their programmes.

CONCLUSIONS

Regional communities need all the help they can get. The combination of ageing populations with out-migration, the ongoing pressure of climate change, and (more recently) Covid-19 means that they are struggling. Community composition, identity, knowledge and resilience are being impacted. Volunteers are a core resource in such communities, offering intergenerational collective action that build social capital and a sense of community identity, and, ultimately, community resilience. In this paper we have explored the role played by young volunteers and how their contribution may be maximized through appropriate recruitment, organization mediums and structures. We found that young volunteers play an important role in regional communities, but that existing models for volunteering are not always appealing to young people. We suggest that a model which provides diverse, fun and event-based volunteering opportunities – driven by social media driven communications – will build youth volunteering. This will, in turn, consolidate community identity, resilience, intergenerational cohesiveness and social capital. The role of core recreational institutions such as local schools, Star Club and the YAC are pivotal to future youth volunteering as they can be bridging institutions assisting to build community–youth partnerships. Role modelling by family members will maintain intergenerational capital, becoming central to incentivising youth to volunteer more. As such, new forms of volunteering have the potential to play a transformational role in the future of Australia’s regional communities as they face unprecedented future challenges.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We acknowledge the First Nations peoples on whose lands we travelled to do this project. We would also like to acknowledge all the agencies and individuals in the Legatus Region who made themselves available to speak with us. We thank the University of Adelaide for giving us access to software, IT, phone and copying services and finally we thank the Legatus Group for commissioning us to do and for funding the project.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 To set the context, Australia has 565 local government areas (LGAs), which in turn are divided into the following categories: (1) central business districts, (2) metropolitan suburbs, (3) peri-urban areas, (4) regional cities and (5) rural areas. Throughout, when we refer to ‘regional Australia’ or regional communities, we mean peri-urban areas, regional cities and rural areas: basically non-metropolitan areas.

2 The formula is: (1997) $ 13.73 × hours worked by the given volunteer age group on average per capita in 2016 × number of volunteers from all age groups in given LGA = estimated value of volunteering. The coefficient 13.73 is a well-recognized statistical practice employed in previous studies (e.g., Haukka et al., Citation2009), including Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) ones (Trewin, Citation2000, employs the same coefficient to estimate volunteering value).

REFERENCES

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2006a). 2006 Census QuickStats Clare and Gilbert Valleys (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA42110?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2006b). 2006 Census QuickStats Goyder (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2006/quickstat/LGA42110?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2006c). 2006 Census QuickStats Wakefield (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2006/quickstat/LGA42110?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016a). Census of population and Housing: Reflecting Australia (No. 2071.0). https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/[email protected]/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~About%20this%20Release~9999

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016b). Census QuickStats Clare and Gilbert Valleys (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA41140?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016c). Census QuickStats Goyder (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA42110?opendocument

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2016d). Census QuickStats Wakefield (DC). https://quickstats.censusdata.abs.gov.au/census_services/getproduct/census/2016/quickstat/LGA48130?opendocument

- Ainsworth, J. (2020). Feelings of ownership and volunteering: Examining psychological ownership as a volunteering motivation for nonprofit service organisations. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52, 101931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101931

- Aldrich, D. P., & Meyer, M. A. (2015). Social capital and community resilience. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(2), 254–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764214550299

- Astin, A., & Sax, L. (1998). How undergraduates are affected by service participation. Journal of College Student Development, 39(3), 251–263.

- Ballew, M., Omoto, A., & Winter, P. (2015). Using Web 2.0 and social media technologies to foster proenvironmental action. Sustainability, 7(8), 10620–10648. https://doi.org/10.3390/su70810620

- Benton, R. A. (2016). Uniters or dividers? Voluntary organizations and social capital acquisition. Social Networks, 44, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2015.09.002

- Berkes, F. (2009). Evolution of co-management: Role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. Journal of Environmental Management, 90(5), 1692–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001

- Berkes, F., & Ross, H. (2013). Community resilience: Toward an integrated approach. Society & Natural Resources, 26(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920.2012.736605

- Bourne, K., Houghton, K., How, G., Achurch, H., & Beaton, R. (2020). The big movers: Understanding population mobility in regional Australia. Regional Australia Institute.

- Brady, H., Schlozman, K. L., & Verba, S. (1999). Prospecting for participants: Rational expectations and the recruitment of political activists. American Political Science Review, 93(1), 153–168. https://doi.org/10.2307/2585767

- Brown, K., Lipsig-Mumme, C., & Zajdow, G. V. (2003). Active citizenship and the secondary school experience: Community participation rates of Australian youth. Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth Research, 32. https://research.acer.edu.au/lsay_research/36/

- Brueckner, M., Holmes, K., & Pick, D. (2017). Out of sight: Volunteering in remote locations in Western Australia in the shadow of managerialism. Third Sector Review, 23(1), 29–49. https://search.informit.org/documentSummary;res=IELAPA;dn=812787283013878

- Butrica, B. A., Johnson, R. W., & Zedlewski, S. R. (2009). Volunteer dynamics of older Americans. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(5), 644–655. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbn042

- Chenoweth, L., & Stehlik, D. (2001). Building resilient communities: Social work practice and rural Queensland. Australian Social Work, 54(2), 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/03124070108414323

- Chia, J. (2010). Emerging communities before an emergency: Developing community capacity through social capital investment. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 25(1), 18–22. https://ajem.infoservices.com.au/items/AJEM-25-01-07

- Chia, J. (2011). Communicating connecting and developing social capital for sustainable organisations and their communities. Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, 17(3), 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2043-9059(2014)0000006002

- Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., Ridge, R. D., Copeland, J., Stukas, A. A., Haugen, J., & Miene, P. (1998). Understanding and assessing the motivations of volunteers: A functional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(6), 1516–1530. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1516

- Collits, P. (2012). Is there a regional Australia, and is it worth spending big on? Policy: A Journal of Public Policy and Ideas, 28(2), 24–29B. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;res=IELAPA;dn=628535628686612

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Conducting mixed methods research. Sage Publications.

- Davies, A. (2008). Declining youth in-migration in rural Western Australia: The role of perceptions of rural employment and lifestyle opportunities. Geographical Research, 46(2), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2008.00507.x

- Davies, A., Lockstone-Binney, L., & Holmes, K. (2021). Recognising the value of volunteers in performing and supporting leadership in rural communities. Journal of Rural Studies, 86, 136–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.05.025

- Davies, J. (2018). “We’d get slagged and bullied”: Understanding barriers to volunteering among young people in deprived urban areas. Voluntary Sector Review, 9(3), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080518X15428929349286

- Davis-Smith, J., Ellis, A., & Howlett, S. (2002). UK-wide evaluation of the Millennium Volunteers Programme. Institute of Volunteering Research, Department for Education and Skills.

- Dean, J. (2016). Class diversity and youth volunteering in the United Kingdom: Applying Bourdieu’s habitus and cultural capital. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015597781

- Denzin, N. K. (2017). Critical qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(1), 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800416681864

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Duarte Alonso, A., & Nyanjom, J. (2016). Volunteering, paying it forward, and rural community: A study of Bridgetown, Western Australia. Community Development, 47(4), 481–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2016.1185449

- Duhé, S. (2007). New media and public relations. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Duke, N. N., Skay, C., Pettingell, S., & Borowsky, I. (2009). From adolescent connections to social capital: Predictors of civic engagement in young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(2), 161–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.07.007

- Einolf, C., Chambré, S., Wiepking, P., & Bekkers, R. (2011). Who volunteers? Constructing a hybrid theory. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16(4), 298–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.429

- Flanagan, C. A., Bowes, J. M., Jonsson, B., Csapo, B., & Sheblanova, E. (1998). Ties that Bind: Correlates of adolescents’ civic commitments in seven countries. Journal of Social Issues, 54(3), 457–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1998.tb01230.x

- Gage, R., & Thapa, B. (2012). Volunteer motivations and constraints among college students: Analysis of the volunteer function inventory and leisure constraints models. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(3), 405–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011406738

- Hankinson, P., Rochester, C., & Grounds, J. (2005). The face and voice of volunteering: A suitable case for branding? International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 10(2), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.15

- Hart, D., Donnelly, T. M., Youniss, J., & Atkins, R. (2007). High school community service as a predictor of adult voting and volunteering. American Educational Research Journal, 44(1), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831206298173

- Haski-Leventhal, D., Meijs, L. C., & Hustinx, L. (2010). The third-party model: Enhancing volunteering through governments, corporations and educational institutes. Journal of Social Policy, 39(1), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279409990377

- Haski-Leventhal, D., Ronel, N., York, A., & Ben-David, B. (2008). Youth volunteering for youth: Who are they serving? How are they being served? Children and Youth Services Review, 30(7), 834–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.12.011

- Haukka, S., Robb, W., & Alam, K. (2009). Still putting in measuring the economic and social contributions of older Australians May 2009. National Seniors Australia.

- Hill, J. P., & den Dulk, K. R. (2013). Religion, volunteering, and educational setting: The effect of youth schooling type on civic engagement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52(1), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12011

- Holdsworth, R. (2007). Servants or shapers? Young people, volunteering and the community. [Working Paper 26]. Youth Research Centre. https://education.unimelb.edu.au/yrc/assets/docs/yrc-misc-docs/WP26.pdf

- Hustinx, L., Cnaan, R., & Handy, F. (2010). Navigating theories of volunteering: A hybrid map for a complex phenomenon. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40(4), 410–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2010.00439.x

- International Labour Organisation (ILO). (2011). Manual on the measurement of volunteer work (pp. 1–120). https://www.ilo.org/stat/Publications/WCMS_162119

- Isham, J., Kolodinsky, J., & Kimberly, G. (2006). The effects of volunteering for nonprofit organizations on social capital formation: Evidence from a statewide survey. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(3), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764006290838

- Kay, T., & Bradbury, S. (2009). Youth sport volunteering: Developing social capital? Sport, Education and Society, 14(1), 121–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320802615288

- Kerr, L., Savelsberg, H., Sparrow, S., & Tedmanson, D. (2001). Experiences and perceptions of volunteering in Indigenous and non-English speaking background communities. Social Policy Research Group, University of South Australia.

- Khajehpour, M., & Ghazvini, S. (2011). The role of parental involvement affect in children's academic performance. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1204–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.263

- Koss, R., & Kingsley, J. (2010). Volunteer health and emotional wellbeing in marine protected areas. Ocean & Coastal Management, 53(8), 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2010.06.002

- Kowalski, A., & Jenkins, L. (2015). The role of bridging organizations in environmental management: Examining social networks in working groups. Ecology and Society, 20(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07541-200216

- Kragt, D., & Holtrop, D. (2019). Volunteering research in Australia: A narrative review. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71(4), 342–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12251

- Lareau, A. (2000). Home advantage. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Leader-Elliott, L., Smiles, R., & Vanzo, L. (2008). Volunteers and community building in regional Australia: The creative volunteering training program 2000–2004. Australian Journal on Volunteering, 13(1), 29–38.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

- Lough, B., Carroll, M., Bannister, T., Borromeo, K., & Mukwashi, A. (2018). The thread that binds. Volunteerism and community resilience 2018 State of the World’s Volunteerism Report (SWVR). United Nations Volunteers (UNV) programme. https://volunteeringqld.org.au/docs/UNV_2018_State_of_the_Worlds_Vol_Report.pdf

- Macduff, N., Netting, F. E., & O'Connor, M. K. (2009). Multiple ways of coordinating volunteers with differing styles of service. Journal of Community Practice, 17(4), 400–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705420903300488

- Martin, M., & Henry, A. (2012). Building rural communities through school-based agriculture programs. Journal of Agricultural Education, 53(2), 110–123. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?cluster=16270103575930442421. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2012.02110

- Maru, Y., McAllister, R., & Stafford Smith, M. (2007). Modelling community interactions and social capital dynamics: The case of regional and rural communities of Australia. Agricultural Systems, 92(1–3), 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2006.03.005

- Marzana, D., Marta, E., & Pozzi, M. (2012). Social action in young adults: Voluntary and political engagement. Journal of Adolescence, 35(3), 497–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.08.013

- Mellor, D., Hayashi, Y., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Lake, L., Staples, M., Chambers, S., & Cummins, R. (2009). Volunteering and its relationship with personal and neighbourhood well-being. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(1), 144–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764008317971

- Misener, L., & Mason, D. (2006). Creating community networks: Can sporting events offer meaningful sources of social capital? Managing Leisure, 11(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710500445676

- Moffatt, L. (2011). Engaging young people in volunteering: what works in Tasmania? [Full report]. Hobart: Volunteering Tasmania. https://www.volunteeringtas.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Engaging-Young-People-Report-Executive-Summary.pdf

- Moorfoot, N., Leung, R., Toumbourou, J., & Catalano, R. (2015). The longitudinal effects of adolescent volunteering on secondary school completion and adult volunteering. International Journal of Developmental Science, 9(3–4), 115–123. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-140148

- Muddiman, E., Taylor, C., Power, S., & Moles, K. (2019). Young people, family relationships and civic participation. Journal of Civil Society, 15(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2018.1550903

- Okun, M., O’Rourke, H., Keller, B., Johnson, K., & Enders, C. (2015). Value-expressive volunteer motivation and volunteering by older adults: Relationships with religiosity and spirituality. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 70(6), 860–870. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu029

- Omoto, A., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.671

- Omoto, A., Snyder, M., & Martino, S. (2000). Volunteerism and the life course: Investigating age-related agendas for action. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 22(3), 181–197. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324834BASP2203_6

- Paintsil, I. (2019). Religiosity, parental support, and formal volunteering among Teenagers. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. http://search.proquest.com/docview/2229780858/

- Perks, T., & Konecny, D. (2015). The enduring influence of parent’s voluntary involvement on their children’s volunteering in later life. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie, 52(1), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12062

- Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster. https://scholar.google.com.au/scholar?cluster=125483733959826388

- Regnault, A., Willgoss, T., & Barbic, S. (2018). Towards the use of mixed methods inquiry as best practice in health outcomes research. Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, 2(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-018-0043-8

- Reid, W., Berkes, F., Wilbanks, T., & Capistrano, D. (Eds.). (2006). Bridging scales and knowledge systems: Linking global science and local knowledge in assessments. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment and Island Press. https://scholar.google.com.au/scholar?cluster=308912859922897152

- Salahuddin, M., Tisdell, C., Burton, L., & Alam, K. (2015). Social capital formation, internet usage and economic growth in Australia: Evidence from time series data. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 5(4), 942–953.

- Sharp, E. N., & Carter, H. (2020). Examination of how social media can inform the management of volunteers during a flood disaster. Journal of Flood Risk Management, 13(4), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfr3.12665

- Stukas, A., Daly, M., & Cowling, M. J. (2005). Volunteerism and the creation of social capital: A functional approach. Australian Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 35–44.

- Stukas, A., & Dunlap, M. R. (2002). Community involvement: Theoretical approaches and educational initiatives. Journal of Social Issues, 58(3), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00268

- Stukas, A., Snyder, M., & Clary, E. (2016). Understanding and encouraging volunteerism and community involvement. The Journal of Social Psychology, 156(3), 243–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2016.1153328

- The National Youth Agency. (2007). Young people’s volunteering and skills development. Department of Education and Skills. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6643/1/RW103.pdf

- Tonts, M. (2005). Competitive sport and social capital in rural Australia. Journal of Rural Studies, 21(2), 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2005.03.001

- Torres, G. (2003). The future of volunteering: Children under the age of 14 as volunteers. ServiceLeader.org: For Volunteer Managers. http://www.serviceleader.org/new/managers/2004/06/000244print.php

- Trewin, D. (2000). Unpaid work and the Australian Economy 1997. Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Verba, S., Schlozman, K., & Brady, H. (1995). Voice and equality: Civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press.

- Volunteering Australia. (2015, July 30). New definition of volunteering in Australia. [Media Release]. Volunteering Australia. https://www.volunteeringaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/300715-Media-Release-New-Definition-of-Volunteering-FINAL.pdf

- Walsh, L., & Black, R. (2015). Youth volunteering in Australia: An evidence review. Australian Research Alliance for Children and Youth. https://www.aracy.org.au/publications-resources/command/download_file/id/275/filename/Youth-volunteering-in-Australia-evidence-review.pdf

- Wang, L., & Fahey, D. (2011). Parental volunteering: The resulting trends since no child left behind. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(6), 1113–1131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010386237

- Warburton, J. (2010). Volunteering as a productive ageing activity: Evidence from Australia. China Journal of Social Work, 3(2–3), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17525098.2010.492655

- Whittaker, A., & Banwell, C. (2002). Positioning policy: The epistemology of social capital and its application in applied rural research in Australia. Human Organization, 61(3), 252–261. https://doi.org/10.17730/humo.61.3.bcr1xbyn7cam8xp3

- Wild, R. (1974). Bradstow: A study of class, status and power in an Australian country town. Angus and Robertson Publishers.

- Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215