ABSTRACT

With the growth of children’s population in cities, research on children’s views about their urban lives has gained traction in the literature. Contributing to such a research agenda, this study examines the perception of slum-dwelling Filipino children of their sonic environment, which is an under-researched topic. Analysis focuses on how children’s experiences both create and are shaped by the soundscape of their slum spaces. Drawing from unstructured interviews with Filipino children (aged 9–12 years) in San Jose del Monte City, this study articulates what comprises children’s sonic environment in slums and how they make sense of their soundscapes. Findings suggest that children have a complex sonic relationship with their spaces beyond physical aspects, offering another dimension to thinking about children’s auditory encounters. This work hopes to spark conversations on how soundscapes can inform thinking about and conducting regional studies.

1. INTRODUCTION

Approximately 1 billion children live in cities (Nyahuma-Mukwashi et al., Citation2020). The increasing number of children residing in urban settings has noteworthy implications for rethinking children’s role as signposts of the city’s well-being (Freeman & Tranter, Citation2011). As Peñalosa and Ives (Citation2004, p. 2) put it, ‘children are a kind of indicator species. If we can build a successful city for children, we will have a successful city for all people’. Along with the recognition of children as urban stakeholders, research interest about children in cities has grown with an emphasis on understanding children’s perspectives and interests as urban citizens (e.g., Malone & Rudner, Citation2011; van Vliet & Karsten, Citation2015), encouraging urban practises that support children’s meaningful engagement within cities. In this regard, the voices of underprivileged children, such as those living in underclass regions of the city, are an important focus because they are stakeholders with elevated risks due to spatial inequalities (Derr et al., Citation2013). It is thus critical to amplify the voices of children in urban poor regions, whose reality is often characterized by poverty, inequality and fragility.

This article examines how children perceive their soundscapes in an urban slum in the Philippines. In children’s sensory exposure, sound is part of what Ansell (Citation2009, p. 200) calls the ‘embodied encounters’, which are crucial experiences for children because of their ‘emotional, cognitive and imaginative engagement’ with everyday experiences. A child-friendly sensory experience in urban settings is also part of the thrust of the child-friendly cities (CFC) framework as prompted by the rights-based approach of the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) to address the underrepresentation of children in urban development (Malone, Citation2006). Yet, children’s sonic experience is an under-researched area in urban studies, particularly in rapidly urbanizing regions in the Global South. As such, this study intends to have twofold contributions to the fields of children’s geographies and regional science by highlighting the relevance of children’s sonic experience in the marginal regions of the city (Power, Citation2007; Hörschelmann & van Blerk, Citation2012; Mahabir et al., Citation2016). As a contribution to research that makes use of sensory experiences to capture the ‘messy, fleshy’ aspects of daily life (Katz, Citation2001, p. 711), this work opens discussions in exploring the complex dilemmas and challenges in the lives of young slum dwellers such as issues of exclusions and inequalities in access to conducive auditory experiences. Such discussions are important to make visible the link between spaces and senses through looking at the city’s marginal regions.

2. GEOGRAPHIES OF SOUND AND CHILDREN

Building on acoustic ecology (Schafer, Citation1977), research interests exploring the relationship between spaces and sonic environments have surged in the past decade (Axelsson, Citation2010; Cerwén et al., Citation2017). Focusing on soundscapes-spatiality dynamics, geographers engage in ‘how sound prompts highly visceral experiences … [and] offers possible insights into how sounds are worked, reworked or silenced in everyday lives in meaningful ways’ (Duffy et al., Citation2011, p. 468). Such embodied lived experiences are part of a multisensory immersion of individuals in their socio-environmental interactions (Rodaway, Citation1994; Thrift, Citation2008). This sub-field was developed by scholars such as Wrightson (Citation2000) who further discussed terminologies such as ‘sound signals’ or ‘foreground sounds’ and ‘soundmark’ (analogy for landmark).

However, while the geography of sounds has gained traction, little qualitative research focuses on the sonic environments in marginalized urban contexts such as slums. Most extensive studies on this topic are quantitative measurements of noise exposure levels and sensitivity to traffic and airport noise in developed countries (Ruiz-Padillo et al., Citation2016). This is pertinent to children in slums as they are heavily exposed to noise pollution such as road traffic, building construction and yelling (Sieber et al., Citation2019; Choi et al., Citation2020). Whilst everyone is affected by noise pollution, children are particularly at risk of the harm from excessive noise exposure as they still need to develop coping repertoires against harmful noise. Children may be unable to identify and avoid sources of noxious noise (Tamburlini et al., Citation2002). Since children are at a critical stage of learning development, exposure to noise hampers their learning, leading to short-term learning deficits or lifelong impaired cognition (Thakur et al., Citation2016). More specifically, children with learning or attention difficulties such as dyslexia and hyperactivity are particularly vulnerable due to the elevated risks of hearing loss (Carvalho et al., Citation2005). In lower income groups, such conditions are often undiagnosed, leaving child-specific needs unattended and exacerbating the vulnerabilities of underprivileged children. Such noise hazards are interwoven with dehumanizing slum conditions such as poor housing and sanitation and scarcity of water and electricity (Pankhurst & Tiumelissan, Citation2013). To address this gap, this work conducts qualitative interviews with slum-dwelling children to further substantiate the literature on auditory experiences of children in urban slum regions with an approach that draws heavily on children’s narratives (Corsaro, Citation2015).

3. ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

To understand the children’s embodied sound encounters, this work adopts Feld’s (Citation1996) acoustemological framework, referring to appreciation of sound as a tool to understand one’s surroundings through recognizing the ‘potential of acoustic knowing, sounding as a condition of and for knowing, of sonic presence and awareness as potent shaping forces in how people make sense of experiences’ (p. 97). Children use sounds as alternative ways of engaging with their environment (Deans et al., Citation2005). Child–sound dynamics constitute reaction and association to a perceived auditory experience, an alternative for the better-known visual epistemology as a dominant sensory modality. Moreover, children develop their sonic knowledge through an interplay between hearing and the other senses as acoustemology connects auditory recognition with the entire sensory experiences of individuals.

This work integrates Feld’s acoustemological framework with the notion of soundscapes referring to ‘mediator[s] between listener and the environment’, in which individuals develop relationships with their sonic environment (Truax, Citation1999, cited in Wrightson, Citation2000). Note that although Feld criticizes the concept of soundscapes because it arguably conveys a fixity of sounds among detached observers, this paper uses the term ‘soundscape(s)’ because location is of interest. Location is important because the acoustic environment is reliant on ‘the sources present, the location of the receiver, and the propagation conditions along the path’ (Brown et al., Citation2016, p. 2). To further describe children’s sonic experiences, this work adopts the soundscape descriptors by Davies et al. (Citation2013) on the diversity of sound encounters – a cacophony describes a soundscape associated with negative listening experiences; a hubbub refers to sounds perceived positively; constant sounds refer to a sound that almost never leaves, usually covering all other sounds; and temporal sounds come at repeated intervals.

4. METHODOLOGY

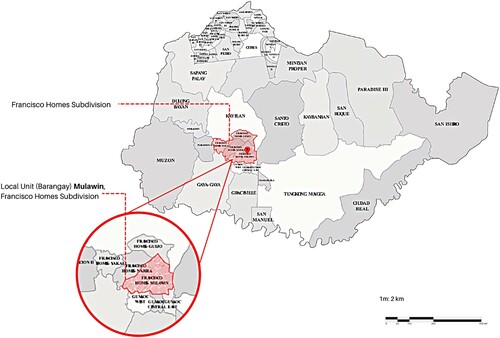

Through unstructured interviews, children (9–12 years old, n = 25) described their perceptions about their urban soundscapes. Aside from developing rapport with children, the nature of unstructured qualitative interviews enable children to tell their stories with minimal interruptions as the interviewer maintains an active listener role (Irwin & Johnson, Citation2005). The field site is a slum in Mulawin, Francisco Homes located in San Jose del Monte City (SJDM), a mid-tier city in central Philippines (). It is an area of interest because of its rapid population growth, resulting in high proportions of slums. The neighbourhood stands in an approximately 1 hectare area at the city’s periphery. The children described their neighbourhood’s soundscapes and their opinions on the opportunities and challenges arising from their sonic environment. To keep a comfortable atmosphere for children, interviews were conducted in groups of three or four peers – seven triads and one quartet (Corsaro, Citation2015). The children’s names were documented but not mentioned in the article to secure their anonymity. The statements expressed in the children’s local language (Tagalog) were translated by the author. Interviews were evaluated using qualitative thematic analysis. The interview’s time frame was during the Modified General Community Quarantine (MGCQ) in SJDM City, in which children are still encouraged to remain in their residences at all times (Inter-agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases, Citation2020). However, indoor and outdoor physical activities are allowed under the conditions of following the minimum public health standards of wearing masks and keeping physical distancing protocols.

Figure 1. Map of San Jose del Monte City, Bulacan, Philippines.

Source: Base map is from TilmannR shared through Wikimedia Commons (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ph_fil_san_jose_del_monte.svg) distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en).

5. FINDINGS: CHILDREN’S SOUNDSCAPES

5.1. Multiple sonic environments

The interviews reveal that children navigate multiple sonic environments embedded in their slum conditions. Generally, their soundscapes mostly consist of biophonic, geophonic or anthrophonic sounds (Pijanowski et al., Citation2011) (). Biophonic sounds, or sounds with biological origins, often come from animals such as birds, insects and domestic pets. Geophonic sounds, or sounds generated by physical processes, emerge from rain, wind, thunder, earthquakes and sometimes running water. Children also hear human-made or anthrophonic sounds such as talking, murmuring and shouting from their neighbours or from chatting passers-by and sounds induced by human activities such as cars, loudspeakers and the slamming doors of neighbours. Since most of these children live in what are considered ‘interim’ or ‘interstitial landscapes’, there are sounds which children are more exposed to than others. For example, children usually hear some people chatting secretly in hidden parts of their neighbourhood.

Figure 2. Sources of sounds in slums in San Jose Del Monte City: biophonic sound from a rooster (top left), anthrophonic sounds from human neighbours (bottom left) and geophonic sounds from the creek (right).

Photo: Erlinda Andal.

The spatiality of slums and their properties primarily include substandard housing conditions such as crowding, poor indoor air quality, low light and low noise filters. It comes as no surprise then that noise penetrates children’s daily lives. The immediate surrounding of their neighbourhood is a narrow street 20 metres away from the main road, in which children can hear cars, motorcycles and tricycles on a regular basis. The emergence of high-rises in the city means that children hear building construction. However, the green spaces offset the noise hazards nearby, producing sounds of nature such as the wind and chirping of birds. Such a slum environment harbours a specific context that contains the structure that enables and restricts certain activities. For instance, children are able to hear trees and birds more audibly during daylight because it is a safe time to go to the unlit green areas. Furthermore, since the houses are not soundproof, children’s waking hours are determined by the movements of people in their neighbourhood. While some children are able to sleep with noise from neighbours working or chatting outdoors, most of them wake up once more people in the neighbourhood start moving. Thus, the materiality of their spaces intervenes everywhere in characterizing children’s sonic encounters.

The children are aware that some urban planning priorities of SJDM can change the myriad of their soundscapes. While SJDM aims to maintain an eco-friendly city for touristic purposes, the city is a centre for industrial activities and transportation projects. For instance, the city is currently undergoing infrastructural developments as part of the Manila Metro Rail Transit (MRT) Line 7 project, a 22.8 km-long elevated rapid transit line (CNN Philippines, Citation2021). Such projects can affect children’s soundscapes as they reside near the station site construction. Moreover, the growing economic activities dominating the spaces of both the residential and public areas of the city may imply changes in the sonic environment of slums as more residents come in. Yet, the participants perceive their present soundscapes and the future changes in their city as realities to be accepted. This view is linked with the priorities of slum dwellers in terms of surviving urban life. For slum dwellers, living in an optimal sonic environment comes secondary to avoiding eviction or homelessness. When asked about how they feel regarding their conditions, several participants expressed indifference as they have no control over the urban development of SJDM. In the words of one participant: ‘I don’t really have a choice to complain about the sounds I hear because there’s not many places where we can stay’ (11 years old). The impermanence of their living conditions does not enable them to invest in sonic modifications of their habitations according to their preferences. Instead, slum-dwellers engage in a trade-off between sonic comfort and more urgent needs, a tactic they apply to their hostile conditions (de Certeau, Citation1984). For instance, since their houses are badly ventilated, they need to leave their doors open even if it means hearing footsteps, voices and the snores of neighbours sleeping outdoors.

5.2. Soundscape associations

The slum soundscapes produce certain evocations of emotions, imaginations and recollections of children’s auditory experiences. While the respondents have not been tested on noise annoyance level, they are aware of what gives them a cacophony or a negative auditory experience. Anthroponic sounds such as screaming, chatty passers-by or bantering neighbours create a sense of noise annoyance. As one child mentions: ‘The chatty adults somehow disturb me when I try to sleep at night’ (10 years old). In contrast, positive sounds (hubbubs) come from animal sounds such as crickets and birds, noting that ‘the sound of birds and trees are calming, almost adventurous’ (12 years old). The participants were adamant in giving evocative descriptions to sounds such as ‘funny sound’ (e.g., funny laugh) in order to better explain how sounds make sense to them. Meanwhile, part of children’s sonic environment are sounds they connect with time such as constant sounds from the wind whispering and rustling leaves, which can inspire them to do an activity: ‘It feels relaxing to hear the sound of the wind because I know it’s a good time to get out of the house, get some fresh air’ (12 years old). They also hear sounds at repeated intervals (temporal) such as a rooster’s crow in the morning, the sound of the waste truck once a week or the regular crying of babies in the afternoon. Knowing regularities of sounds at a certain time provides children cues to their daily activities and enables children to decide on their actions. For example, expecting a rooster’s crow in the morning means it is time to wake up; hearing babies crying in the afternoon serves as a signal for doing their mid-afternoon chores such as cleaning their houses or collecting water from the nearby stream.

5.3. Territories and micro-politics of soundscapes

Children recognize their neighbourhood as auditory territories. They create an imagined territory by enlivening the sonic environment of their neighbourhood through singing or playing do-it-yourself percussion instruments from ice cream cans or stones in jars. However, caught in a border territorial issue, children are aware that they are perceived as ‘noise-makers’ by official city-dwellers, who legally own land and houses in the subdivision where the slum community is found. For example, children experience being silenced by restricting the volume of their voices while playing in the streets, as imposed by official residents. One says: ‘Probably, making loud sounds while playing is a more risky thing than crossing the streets. I feel scared whenever subdivision residents pass by’ (11 years old). The children mention that stigma (e.g., drug addicts, criminals and prostitutes) might be part of the general exclusion they experience: ‘Some people accuse us of being parasites in the city who just create noise and make the streets dirty’ (10 years old). Yet, children offer a counter-narrative to such accusations by arguing that official residents also produce noise. One argues: ‘But the residents are also noisy and we feel annoyed at times too. But because we are “squatters”, they ignore us’ (12 years old). This shows the complex territoriality and sonic micro-politics of who can make sounds, at which volume and where. Such sonic micro-politics has to do with making invisible the needs of children for self-expression under the veil of the ‘rights’ of official residents as rightful owners of spaces in the city. This discourse of ownership undermines the larger structural injustice of homelessness. This slum ‘life-space’ thus reveals the uneven sonic rights and soundscape boundaries that cut across the different social classes.

6. IMPLICATIONS: RETHINKING CHILDREN’S AUDITORY ENCOUNTERS WITH SPACES

The interviews suggest that children have a complex sonic relationship with their neighbourhood, opening a space to discuss children’s auditory encounters in informal settlements. Using the framework of acoustemology as a way of knowing, the interviews show that children’s perception of their soundscapes is a multidimensional process in which they identify sound sources, recall familiar or unfamiliar sounds, calculate the timing during which sounds are heard, and know their role in sound-making. Three main insights transpire from these results.

First, discussing children’s soundscapes aligns with the literature that foregrounds the inextricable link between acoustic environment and the events within this environment (Cerwén et al., Citation2017; Brown et al., Citation2016). The auditory experiences of children highlight the importance of espousing sensory experiences to understand certain areas. In the children’s experience, sounds play a role in shaping identities within territories, which emanate from different life forms (Axelsson, Citation2010). In this regard, children contribute to such knowledge generation and discussion as they are not passive listeners of their soundscapes: they can characterize the sonic diversity of the spaces they inhabit and identify the significant sounds for them. This provides new perspectives on ways to understand a given area from children’s local experiences. Soundscapes serve as an entry-point to reflect children’s embodied encounters and intimate experiences, which in part inform their views, actions, and decisions. This is also suggestive of the need to take heed of the ignored senses and hidden perspectives in slum areas as an alternative perspective that refocuses our gaze from grand urban planning to small informalities in urban areas (Amin & Thrift, Citation2002). The responses of children regarding their slum soundscapes hint at policy implications that pay attention not only to reducing hazardous sounds but also to add beneficial sounds. The way an optimal urban soundscape is conceptualized usually comes in neutrality or lessening noise levels of the immediate physical environment. Yet, as the children explained, there are gains in the presence of hearing pleasant sounds too. As such, policymaking may benefit from understanding children’s relationships with various sounds together with their social practices, values and visions with regard to the meanings of sounds in their environment.

Second, the results of this study contribute to discussions on the heterogeneity of informalities (Harris, Citation2018; Roy, Citation2005) – simultaneously reflecting and challenging the narrative of deprivation associated with informalities. On the one hand, the silencing of slum-dwelling children reinforces sonic-spatial exclusion and stigmatization (Pankhurst & Tiumelissan, Citation2013). This evokes conversations about the often unrecognized sound marginalization in urban spaces. Sound-making becomes a context for isolation and exclusion, where the official city residents can demand sonic behaviours from children. But on the other hand, the children were also able to interpret their soundscapes as empowering in terms of appreciating the diversity of auditory experiences at their disposal (Davies et al., Citation2013). Children’s counter-narratives about the ‘noise’ generated by homeowners suggest the need to articulate whose sound is considered as noise and by whom. This contrasting character of slum soundscapes contributes to an understanding of urban processes, especially in developing cities in the Global South. In particular, the site featured in this paper provides a lens to appreciate the complexity of sonic environments in urban informalities. Slum soundscapes thus complicate how urban dwellers reclaim spaces through the politics of sounds. Such observations are indicative of the urban soundscapes as multidimensional and that there is a plurality of possible sonic environments and ways of knowing through sounds that might be hidden.

Finally, despite living in vulnerable spaces, children are able to demonstrate agency to shape a culture of sonic sensibilities within their fragile contexts. In their adjustment to the realities of slum life, children not only adapt to their sonic environment but also compensate for the unpleasant sounds by enriching the sonic diversity in their neighbourhood, whether this emerges from singing or creating their own ‘funny’ sound codes. It is through such trivial but nonetheless significant acts that the children open a creative space for diversifying their neighbourhood’s soundscapes. However, this is not to equate children’s agency as a practice of free will against social structures (Hammersley, Citation2017), as informed by individualist principles over collective good (Twum-Danso Imoh & Ansell, Citation2015). Rather, the agency that the children have shown reflects interdependence with their sonic environment, highlighting children’s connection with others in their neighbourhood. This is an important point to avoid seeing children’s agency through an individualistic lens. As the interviews demonstrate, children have the desire to make and maintain group solidarity and interdependence.

As such, future research will benefit from further exploring how soundscapes become sources of agency and empowerment for slum-dwelling children. First, since there has been little work on children’s sonic environments in urban slums, especially in developing countries, it is hoped that soundscape research takes off in the analysis of children’s geographies in the global South. Second, the interviews in this work indicate the need to further understand the role of sounds in urban spatial exclusion, including insights from those with hearing impairments and their relationship with the urban soundscape. Third, it is important to deep dive into the combination of sensory experiences – sightscapes, touchscapes, smell and tastescapes – of children and their interlink ages with soundscapes in urban environments. Such a research agenda resonates with the thrust to expand our understanding of urban culture among marginalized groups with the shifting and tenable materialities of their spaces in the city. These suggestions can be of best use to researchers, policymakers and practitioners to develop urban practices that take into account the seemingly trivial aspects of children’s urban lives which are crucial for their development.

7. CONCLUSIONS

Using a child-oriented analytical lens, this paper has examined the complex audio-spatial lives of children in informal urban areas. An auditory experiences perspective offers new ways to understand such marginalized areas and how they fare within the broader urban regions to which they belong, not only in terms of ‘development’ but also the oftentimes ‘invisible’ practices. Examining children’s soundscapes, thus, offers yet another strategy and perspective to thicken the data used in urban and regional research on informalities, while shifting the gaze from the formal urban terrains towards the more hidden areas.

Whilst regions touch upon group-bound and large-scale territories, soundscapes and informalities exude the uniqueness of localities as we make sense of them within specific contexts. However, an examination of children’s soundscapes at the local scale as an entry-point of discussion underscores that soundscapes can gauge processes at higher scales in regional contexts. The auditory experiences of slum-dwelling children evince broader regional issues such as sound micro-politics as consequences of neoliberal discourse of regional ‘development’; inequalities in sonic health amongst the peripheries; to the sonic hazards reflecting the exclusionary tendencies against informalities in urban and regional planning. Regional studies can be sensitized to the varied experiences of the everyday local spaces of ordinary citizens on the ground. Indeed, while children’s everyday soundscapes might be trivial, their lives are nevertheless impacted by the bigger morphology of their regions. As such, the triviality of soundscapes in informalities calls for seeking a regional dialogue to better conceptualize the broader applicability of children’s experiences from informalities to regional imaginaries.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2002). Cities: Reimagining the urban. Polity Press.

- Ansell, N. (2009). Childhood and the politics of scale: Descaling children’s geographies? Progress in Human Geography, 33(2), 190–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090980

- Axelsson, Ö. (Ed.). (2010). Designing soundscape for sustainable urban development. Conference Proceedings, 30 September – 1 October 2010 Stockholm: Environment and Health Administration.

- Brown, L., Gjestland, T., & Dubois, D. (2016). Acoustic environments and soundscapes. In J. Kang & B. Schulte-Fortkamp (Eds.), Soundscape and the built environment (pp. 1–16). Taylor & Francis Group.

- Carvalho, W. B., Pedreira, M. L., & de Aguiar, M. A. (2005). Noise level in a pediatric intensive care unit. Journal de Pediatria, 81(6), 495–498. https://doi.org/10.2223/JPED.1424

- de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. University of California Press.

- Cerwén, G., Wingren, C., & Qviström, M. (2017). Evaluating soundscape intentions in landscape architecture: A study of competition entries for a new cemetery in Järva, Stockholm. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 60(7), 1253–1275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2016.1215969

- Choi, E., Bhandari, T. M., & Shrestha, N. (2020). Social inequality, noise pollution, and quality of life of slum dwellers in Pokhara, Nepal. Archives of Environmental & Occupational Health, 77(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/19338244.2020.1860880

- CNN Philippines. (2021). MRT-7, more than 50% complete, set to open by Dec. 2022. https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2021/2/19/mrt-7-more-than-50-percent-complete-set-to-open-dec-2022.html.

- Corsaro, W. (2015). The sociology of childhood. SAGE.

- Davies, W. J., Adams, M. D., Bruce, N. S., Cain, R., Carlyle, A., Cusack, P., Hall, D. A., Hume, K. I., Irwin, A., Jenning, P., Marselle, M., Plack, C. J., & Poxon, J. (2013). Perception of soundscapes: An interdisciplinary approach. Applied Acoustics, 74(2), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apacoust.2012.05.010

- Deans, J., Brown, R., & Dilkes, H. (2005). A place for sound: Raising children’s awareness of their sonic environment. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 30(4), 43–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693910503000407

- Derr, V., Chawla, L., Mintzer, M., Cushing, D., & Van Vliet, W. (2013). A city for all citizens: Integrating children and youth from marginalized populations into city planning. Buildings, 3(3), 482–505. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings3030482

- Duffy, M., Waitt, G., Gorman-Murray, A., & Gibson, C. (2011). Bodily rhythms: Corporeal capacities to engage with festival spaces. Emotion, Space and Society, 4(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2010.03.004

- Feld, S. (1996). Waterfalls of song: An acoustemology of place – Resounding in Bosavi, Papua New Guinea. In S. Feld, & K. H. Basso (Eds.), Senses of place (pp. 91–135). School of American Research Press.

- Freeman, C., & P. J. Tranter. (2011). Children and their urban environment: Changing worlds. Washington, DC: Earthscan.

- Hammersley, M. (2017). Childhood studies: A sustainable paradigm? Childhood (Copenhagen), 24(1), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568216631399

- Harris, R. (2018). Modes of informal urban development: A global phenomenon. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412217737340

- Hörschelmann, K., & van Blerk, L. (2012). Children, youth and the city. Routledge.

- Irwin, L. G., & Johnson, J. (2005). Interviewing young children: Explicating our practices and dilemmas. Qualitative Health Research, 15(6), 821–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304273862

- Katz, C. (2001). Vagabond capitalism and the necessity of social reproduction. Antipode, 33(4), 709–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00207

- Mahabir, R., Crooks, A., Croitoru, A., & Agouris, P. (2016). The study of slums as social and physical constructs: Challenges and emerging research opportunities. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 399–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1229130

- Malone, K. A. (2006). United Nations: a key player in a global movement for child friendly cities. In B. Gleeson, & N. Sipe (Eds.), Creating child friendly cities: Reinstating kids in the city (pp. 13–32). Routledge.

- Malone, K., & Rudner, J. (2011). Global perspectives on children’s independent mobility: A socio-cultural comparison and theoretical discussion of children’s lives in four countries in Asia and Africa. Global Studies of Childhood, 1(3), 243–259.

- Nyahuma-Mukwashi G., Chivenge M., & Chirisa I. (2020). Children, urban vulnerability, and resilience. In Brears R. (Ed) The Palgrave encyclopedia of urban and regional futures (pp. 1–8). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51812-7_90-1

- Pankhurst, A., & Tiumelissan, A. (2013). Living in urban areas due for redevelopment: Views of children and their families in Addis Ababa and Hawassa. Young Lives Working Paper 105. https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/wp105-pankhurst-redevelopment-urban-slums%20.pdf.

- Peñalosa, E., & Ives, S. (2004). The politics of happiness. Land and people. Albuquerque Model City Council Curriculum. https://www.commoncause.org/new-mexico/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/07/abq-model-city-council-lesson-2-penalosa.pdf.

- Pijanowski, B., Villanueva-Rivera, L., Dumyahn, S., Farina, A., Krause, B., Napoletano, B., Gage, S., & Pieretti, N. (2011). Soundscape ecology: The science of sound in the landscape. BioScience, 61(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.3.6

- Power, A. (2007). City survivors: Bringing up children in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Policy Press.

- Republic of the Philippines, Inter-agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infectious Diseases. (2020). Omnibus guidelines on the implementation of community quarantine in the Philippines. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/downloads/2020/10oct/20201008-IATF-Omnibus-Guidelines-RRD.pdf.

- Rodaway, P. (1994). Sensuous geographies: Body, sense and place. Routledge.

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- Ruiz-Padillo, A., Ruiz, D. P., Torija, A. J., & Ramos-Ridao, Á. (2016). Selection of suitable alternatives to reduce the environmental impact of road traffic noise using a fuzzy multi-criteria decision model. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 61, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2016.06.003

- Schafer, M. (1977). The tuning of the world. McClelland & Stewart.

- Sieber, C., Ragettli, M. S., Brink, M., Toyib, O., Baatjies, R., Saucy, A., Probst-Hensch, N., Dalvie, M. A., & Tilmann, R. (2019). Political map of San Jose del Monte, Bulacan [Map]. Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fa/Ph_fil_san_jose_del_monte.svg.

- Tamburlini, G., von Ehrenstein, O. S., & Bertollini, R. (2002). Children’s health and environment: A review of evidence a joint report from the European Environment Agency and the WHO Regional Office for Europe Experts’ Corner. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

- Thakur, N., Batra, P., & Gupta, P. (2016). Noise as a health hazard for children: Time to make a noise about it. Indian Pediatrics, 53(2), 111–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13312-016-0802-7

- Thrift, N. (2008). Non-representational theory: Space, politics, affect. Routledge.

- Truax, B.1999). Handbook for acoustic ecology (2nd ed). Cambridge Street. http://www.sfu.ca/sonic-studio-webdav/handbook/Soundscape.html.

- Twum-Danso Imoh, A., & Ansell, N. (eds.). (2015). Children’s lives in an era of children’s rights: The progress of the Convention on the Rights of the Child in Africa. Routledge.

- van Vliet, W., & Karsten, L. (2015). Child-friendly cities in a globalizing world: Different approaches and a typology of children’s roles. Children, Youth and Environments, 25(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.25.2.0001

- Wrightson, K. (2000). An introduction to acoustic ecology. Soundscape: The Journal of Acoustic Ecology, 1(1), 10–13. https://www.wfae.net/journal.html