ABSTRACT

This paper proposes a system approach to regional economic resilience. This approach argues that regional economies undergo, to varying degrees, changes to their economic system that result from the collective but uncoordinated action of economic actors in an attempt to be resilient to shocks. The system change, particularly focusing on changes to economies’ structure and function, which occurs during and following a shock, determines the type of resilience (i.e., engineering, ecological, evolutionary and transformative) employed by regions. The type of resilience employed can influence regions’ long-term growth trajectory and resilience to future shocks. This approach advances the examination of regions’ resilience capacity, which has largely been ignored in empirical studies of resilience. In doing so, the approach developed in this paper is heuristic rather than deterministic, with the latter characterizing the bulk of the literature. A greater investigation into system change can provide a holistic understanding of resilience. This approach has many advantages, such as developing greater insight into resilience, applying a heuristic method rather than deterministic and examining regions’ adaptive capacity. To advance the system approach, this paper provides greater conceptual clarity of resilience, highlighting the notion's conceptual parameters and rethinking the oppositional context in which the four main types of resilience are commonly discussed. Specifically, it conceptualizes the main types of resilience as complementary rather than oppositional. The overall contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it establishes a greater conceptual framework of resilience. Second, it develops an approach in which regions’ adaptive capacity can be investigated.

1. INTRODUCTION

The 2008 financial crisis adversely affected many countries and had heterogeneous effects on regions globally, with some regions being more adversely impacted than others. The uneven effects of economic shocks or disturbances have been one of the central focuses of regional economic geographers (Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Martin, Citation2012; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Pike et al., Citation2010; Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). Specifically, scholars have attempted to answer the question: Why are some regions more able to successfully mitigate or react to economic shocks than others? (Faggian et al., Citation2018). This question has brought increased attention to the notion of resilience and how regions diverge in economic resilience.

Since the late 2000s, resilience has become the new buzzword, or the zeitgeist, in the economic geography literature (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015, Citation2020). The notion of regional economic resilience (RER) has gained substantial attention from academics, policymakers and practitioners alike because it has real implications for the livelihood of households globally (Bristow & Healy, Citation2020). However, it has not been without critique (Hanley, Citation1998; Hassink, Citation2010; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2015). RER has been criticized as being a fuzzy concept, requiring conceptual clarity (Pendall et al., Citation2010) and development, and a stronger empirical base (Crespo et al., Citation2017). For instance, there is no universally accepted definition of resilience, with four main competing types of resilience – engineering, ecological, evolutionary and transformative – circulating in the literature (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020). Scholars have attempted to address these criticisms by providing a more precise conceptual definition and theoretical understanding of RER (Boschma, Citation2015; Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Crespo et al., Citation2017; Evenhuis, Citation2017; Hassink, Citation2010; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Pendall et al., Citation2010). Despite the progress that has been made in the resilience literature, more work is still needed. For example, a commonly accepted definition of resilience needs to be developed, rigorous mixed methodological approaches need to be established, and resilience policy options for different spatial scales and localities need to be developed and identified. Additionally, the multi-scalar attributes of resilience and its determinants (e.g., global economic integration) need to be investigated. Finally, a theory of resilience needs to be developed.

Resilience can be broken down into two forms, performance and capacity. Performance refers to the outcome of regions’ reaction to shocks (i.e., evaluating regions’ resilience), while capacity refers to the underlying adaptive process of regions to shocks (i.e., short-term and sudden disturbances) (Banica et al., Citation2020; Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Evenhuis, Citation2017). Both forms of resilience are essential as the former indicates if regions were resilient, and the latter explains why it was resilient. Whilst conceptually both forms of resilience have been acknowledged in the resilience literature, resilience capacity is rarely examined empirically, remaining a ‘black box’, which merits further investigation (Hill et al., Citation2012, p. 249). The bulk of empirical enquiry has been focused on the performance of regional economies to shocks, particularly examining whether or not regions were resilient, and investigating the general determinants of resilience (Brown & Greenbaum, Citation2017; Courvisanos et al., Citation2016; Martin, Citation2012; Ray et al., Citation2017).

Further, empirical studies on the resilience performance or capacity of regions tend to use a deterministic approach, first ascribing the type of resilience used and then measuring the regions’ resilience against the pre-scribe interpretation of resilience (e.g., Brown & Greenbaum, Citation2017; Fingleton et al., Citation2012). The deterministic approach can misrepresent the actual type of resilience employed by regions, which can only truly be determined through examining regions’ resilience capacity. To address this gap, a heuristic approach should be taken to determine the actual type of resilience regions employed. However, currently in the RER literature, no such approach has been put forth. It should be noted that a heuristic approach in this context does not indicate if the region was resilient but simply what type of resilience was employed. Therefore, both forms of resilience are needed to provide a holistic understanding of RER.

The current scholarly focus in the resilience literature is not without merit, as it is used to inform policymakers and practitioners of the determinants of resilience through empirical investigation. However, the dominant focus on performance has overshadowed the examination of regions’ capacity, which is essential for investigating the underlying adaptive process of regions. Similarly, the prominence of the deterministic focus in the resilience literature has impeded a greater investigation of regions’ adaptive capacity. Therefore, the current focus on regions’ performance through a deterministic approach may be one explanation for why, as Christopherson et al. (Citation2010) stated, the resilience literature has tended to be more descriptive than explanatory. In this vein, exploring capacity is essential to provide a holistic and explanatory examination of RER.

This paper aims to address the current gaps in the literature by developing a system approach, a heuristic method, to empirically investigate regions’ resilience capacity. In particular, the system approach examines the system change (i.e., structural and functional) that regions undergo in an attempt to be resilient to a shock. The system change is important as it indicates the type of resilience regions employed. The logic of this approach follows that regional economies are composed of economic actors that produce change within the economy and determine the overall resilience of regional economies (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014). Therefore, examining the system change in a region following a shock is a direct reflection of the collective and self-organizing adaptive behaviour of economic actors.

The paper has three objectives. First, to provide a comprehensive synopsis of RER. Second, to provide an overview of significant conceptual clarifications to the notion of resilience and advance the conceptual clarity and development of RER by illustrating the complementary nature of the main types of resilience. Third, and based on the second objective, to provide a novel approach, a system approach, for examining the notion of resilience, highlighting the importance of investigating the capacities of regions heuristically. This approach has many advantages, such as developing greater insight into RER, employing a heuristic approach and providing more insightful policy implications. The overall contribution of this paper is twofold. First, it provides a greater conceptual framework of resilience. Second, it develops a system approach to help guide and advance the investigation of RER, specifically providing a holistic understanding of resilience. To achieve these objectives and fill the gap in the literature, seminal work on resilience over the past two decades was reviewed, providing a comprehensive overview and in-depth examination of the subject matter.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of RER. Section 3 discusses the recent conceptual clarifications and argues that the four main types of resilience are complementary. Section 4 develops and discusses a new conceptual framework for RER. Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. RESILIENCE

2.1. Resilience: emergence and merits

RER gained rapid popularity in economic geography and spatial economics literature after the 2008 recession (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020), which uncovered the vulnerabilities of regional economies in the current global economic landscape. In particular, the current global landscape is marked by the inseparability of the local and the global (Dicken, Citation2015), in which local disturbances can cause global crises (i.e., the butterfly effect). For example, how a hurricane on the Gulf Coast of Texas can cause the price of corn to surge in Mexico City (Zolli & Healy, Citation2012). The notion of resilience has become popular for five reasons. First, the adverse effects that natural and man-made disasters have on local and regional economies. Second, the effect policies such as austerity policies have on regions when experiencing financial and economic crises. Third, the influence of other disciplines, especially ecology, engineering and behavioural psychology, on economic geography, resulting in cross-fertilization. Fourth, the recognition that shocks can affect the whole economic landscape (Martin, Citation2012). Fifth, the perception that economic and environmental risks are increasing concurrently with globalization, making regional economies more vulnerable to external forces (Christopherson et al., Citation2010; Modica & Reggiani, Citation2015).

The emergence of literature on resilience is not without merit. There are four main reasons to examine resilience. First, the effects of shocks are worked out at the regional level (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015), resulting in regions experiencing the brunt of the adverse impacts of national and global economic shocks. Second, shocks can have direct and long-lasting adverse effects on regional residents’ livelihoods (Bristow & Healy, Citation2020), such as job losses, wage reductions and reduced standard of living. Third, shocks can permanently affect regional economies’ long-term economic trajectory (Crespo et al., Citation2017). Fourth, and intertwined with the third, the varying resilient capacity of regions contributes to the divergence of regional economies (i.e., uneven economic development).

2.2. Overview of regional economic resilience

Despite the advances that have been made in the resilience literature over the past several decades, resilience has yet to develop into a theory. As noted by Swanstrom (Citation2008, p. 2), ‘resilience is more than a metaphor but less than a theory. At best, it is a conceptual framework that helps us to think about regions in new ways, i.e., dynamically and holistically’. However, this conceptual framework is not unproblematic and is in danger of becoming a fuzzy concept, lacking conceptual clarity and incoherent understandings (Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Pendall et al., Citation2010). Therefore, more work needs to be done to address the current shortcomings in the resilience literature. This subsection provides an overview of resilience.

Scholars have identified four main types of resilience – engineering, ecological, evolutionary and transformative – in the context of RER (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020).Footnote1 Engineering resilience refers to the ability of, and the speed at which, regional economies return, or bounce back, to their pre-shock growth path (i.e., structures and functions) when hit by a shock (Davoudi et al., Citation2013; Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). Ecological resilience refers to the ability of regional economies to absorb a shock in order to maintain their growth path. However, once a shock exceeds the threshold a regional economy can absorb, it undergoes system change and shifts to a new and typically less ideal growth path (i.e., equilibrium). Evolutionary resilience – also known as adaptive resilience – refers to economies’ ability to maintain their core function despite the economic shock by reorienting and reorganizing their structure to an existing or new and more favourable growth path. This interpretation of resilience as structural adaptability infers that resilient economies’ bounce forward’ as opposed to ‘bounce back’ when hit by a shock (Boschma, Citation2015; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015, Citation2020). Transformative resilience refers to a system's ability to reconfigure and create a new set of structures and functions once environmental, social or economic conditions make the current nature of the system untenable or undesirable (Banica et al., Citation2020; Davoudi et al., Citation2012; Walker et al., Citation2004, Citation2006). This interpretation infers that the shock experienced by regional economies is so substantive that it requires a complete transformation, resulting in the reallocation of resources and reorientation of structures and functions to create a more sustainable and stable economic system (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020).

To summarize, the first two types of resilience, which were brought forth by ecologist C. S. Holling (Holling, Citation1973), interpret resilience as maintaining or returning to an equilibrium state. Scholars criticize these interpretations of resilience for employing an equilibrium approach that emphasizes a stable equilibrium state. They argue that regional economies are never actually in a stable state but are in a constant state of uncertainty and change (Christopherson et al., Citation2010; Dawley et al., Citation2010; Hassink, Citation2010). Additionally, the equilibrium approach cannot explain the unevenness of RER (Pike et al., Citation2010). Resistance and recovery are the main focus of these interpretations of resilience (Evenhuis, Citation2017). The last two types of resilience focus on the adaptability, in partial or full capacity, of regional economies, which are comprised of a collection of economic actors (i.e., entrepreneurs, firms and institutions). Resilience, in this view, is a dynamic process that is embedded in and part of the evolution and development of regional economies (Boschma, Citation2015; Crespo et al., Citation2017; Martin, Citation2018). Robustness is the main focus of these interpretations of resilience (Evenhuis, Citation2017).

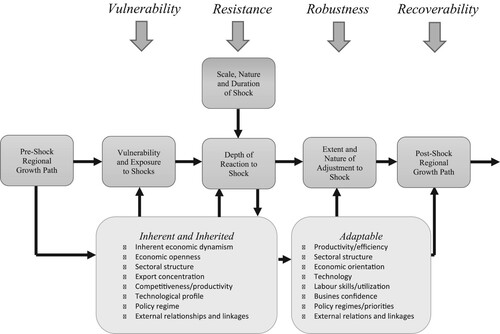

RER is a dynamic process, as highlighted by Martin and Sunley (Citation2015), which consists of four dimensions: vulnerability, resistance, robustness and recoverability (). First, vulnerability refers to the sensitivity of regions’ firms and labour force to different economic shocks. Second, resistance refers to the impact that the shock has on regions’ economies. Third, robustness refers to the ability of firms, institutions and the labour force that encompasses regional economies to adapt and adjust to shocks (i.e., the region's adaptive capacity), which excludes political intervention and external agents and forces. Fourth, recoverability refers to the extent of post-shock recovery of regional growth paths. These four dimensions are necessary to understand the resilience of regional economies.

Figure 1. Four dimensions of regional economic resilience.

Source: Martin and Sunley (Citation2015, p. 13).

Shocks are sudden major disturbances, such as recessions, natural disasters, major industrial closures and pandemics. There are seven broad types of shocks: economic, institutional, organizational, environmental, and technology (Holm & Østergaard, Citation2015), man-made shocks, and epidemic shocks (). Shocks felt in regions can originate either regionally or globally, as well as they can be isolated occurrences (i.e., effects of shocks are contained to one region) or experienced globally (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015). Capitalism is an inherently shock-prone system, and with globalization intensifying over the past three decades, regional economies have become increasingly more vulnerable to shocks, as illustrated by the 2008 recession (Dicken, Citation2015; Hudson, Citation2010; Martin, Citation2018). The modern world is marked by both increasing volatility and global connectivity in which a harmless event in one part of the world can result in an economic catastrophe in other parts (Zolli & Healy, Citation2012). This effect can be termed ‘the butterfly effect’ causing global crises from local disturbances.

Table 1. Eight broad categories of shocks.

When hit by a shock, regional economies can either be resistant (i.e., marginally impacted), resilient (i.e., severely impacted, but recovers) or non-resilient (i.e., severely impacted and does not recover) (Hill et al., Citation2012). When regions experience shocks, they can have hysteretic effects on regional economies, meaning that shocks can alter the long-term growth trajectory of regional economies, resulting, broadly, in post-shock trajectories that have higher or lower growth ceilings or rates than their pre-shock trajectory (Fingleton et al., Citation2012). Regions’ responses to shocks can also shape their resilience to future shocks (i.e., recursive process) (Martin & Sunley, Citation2015). Shocks have heterogeneous effects on regions due to differing economic landscapes and capabilities (Bristow & Healy, Citation2018; Davies & Tonts, Citation2010), resulting in some regions being more adversely affected than others and uneven development between regions, both within and across national economies. Also, the severity of shocks on regions depends on the intensity and duration of shocks, with regions experiencing more severe effects if the shock has high intensity and is prolonged than if the shock has low intensity and is short (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020).

Although shocks are typically discussed as negative events, they can be seen as positive occurrences if they enhance regions’ economic growth trajectory through mechanisms of adaptation and adaptability. For example, Banica et al. (Citation2020) illustrate through multiple case studies how natural disasters can be ‘blessings in disguise’ if they allow regions to develop, grow, and transform in the long run. This is analogous to Schumpeter's ‘gales of creative destructions’ in which outmoded forms of production are swept away (i.e., firm closures) by shocks allowing for more productive forms to emerge (Swanstrom, Citation2008). Gales of creative destruction is the evolutionary process (Schumpeter, Citation2010) in which regions develop, grow and transform, enhancing resiliency, sustainability and competitiveness. Further, regions may receive increased public and private attention during times of economic crisis, resulting in increased resource accumulation, such as financial aid, and infrastructural and organizational development, enhancing regions’ economic landscape and building resiliency (Banica et al., Citation2020). Therefore, shocks can be seen as opportunities for regions to change and enhance their growth trajectory in the long run.

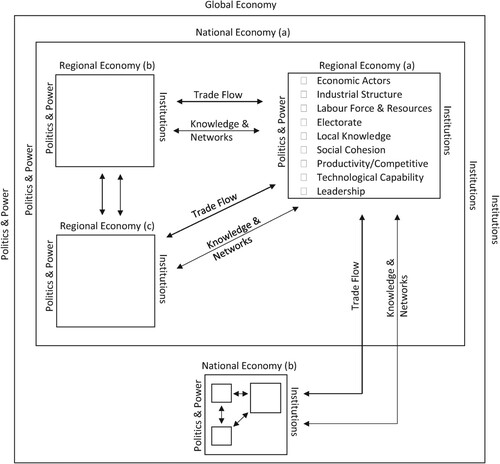

The determinants of RER are complex and dynamic, and are highly dependent on the ‘interplay between factors within regions as well as wider external forces and relationships’ (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014, p. 4; added emphasis). In other words, the determinants of resilience are multi-scalar. provides an overview of the determinants of resilience and illustrates its multi-scalar nature. RER is the product of internal and external key actors (i.e., economic actors, policymakers, practitioners and local leaders), interacting with the region's innate structure (i.e., industrial structure) by drawing on their local labour force (i.e., human capital), resources (i.e., local knowledge and technological capabilities), and economic, social and political landscape (i.e., social cohesion, the electorate and productivity/competitiveness) as well as introducing new external resources (i.e., knowledge pipelines, social networks and trade flows) to the region. The collective action and decision of key actors, although bound by multi-scalar powers, politics and institutions, determine regions’ preparedness and ability to adapt to shocks and, hence, their overall resilience (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014, Citation2020; Davoudi et al., Citation2013; Evenhuis, Citation2017; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015). Although many determinants of RER have been identified (e.g., Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015), they largely remain underdeveloped and underexplored.

3. REGIONAL ECONOMIC RESILIENCE: DEVELOPING CONCEPTUAL CLARITY

The notion of resilience is not without critique, however (Hanley, Citation1998; Hassink, Citation2010; MacKinnon & Derickson, Citation2013; Olsson et al., Citation2015). The main critique of resilience is that it is a fuzzy concept and lacks conceptual value. Much work has been done in the past decade to address these critiques by developing a clearer and more coherent conceptual framework of resilience (Boschma, Citation2015; Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Crespo et al., Citation2017; Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Martin & Sunley, Citation2015). In particular, scholars in economic geography have made two main conceptual clarifications on resilience that, although highly contested and not universally accepted, enhance its conceptual value. First, Martin and Sunley (Citation2015) argue that shocks should solely refer to sudden disturbances and not slow-burning pressures. They state that if shocks are equated to the ‘slow-burning’ pressures that occur incrementally over time (e.g., deindustrialization), the concept gets diluted and indistinguishable from general economic change. Second, the notion of resilience should only be examined in the context of a shock or shocks and hence, distinguished from long-run adaptive growth, or risk the notion of encapsulating a multitude of interpretations, such as long-term competitiveness or sustainability (e.g., Martin & Sunley, Citation2015; Bristow, Citation2010). Thus, resilience refers only to the underlying capacity to adapt to shocks and the overall outcome of regional economies (i.e., resilience capacity and performance) (Evenhuis, Citation2017). These two clarifications provide a clearer and refined conceptual framework of what constitutes a shock (i.e., a sudden disturbance) and in what context resilience should be examined. Simply put, the value of resilience and what distinguishes it from other existing concepts in economic geography stems from its ability to evaluate regional economies’ capacity to cope with shocks (Martin & Sunley, Citation2017).

Building off the previous two conceptual developments of resilience, this paper advances a third conceptual development surrounding the oppositional interpretation of the main types of resilience. The resilience literature distinguishes between the four types of resilience (i.e., engineering, ecological, evolutionary, and transformative resilience), perceiving them as opposing or competing concepts with distinct interpretations (e.g., Martin & Sunley, Citation2020; Pendall et al., Citation2010). However, these concepts should not be considered opposing interpretations but complementary and interdependent, with regional economies’ growth paths and systems’ structure and function as common reference points for definitions of resilience (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Martin & Sunley, Citation2017; Walker et al., Citation2004, Citation2006). For example, Martin and Sunley (Citation2020) argue that as the intensity and duration of shocks increase, regions will have to move from employing engineering to ecological to evolutionary to transformative resilience. Also, Angulo et al. (Citation2018) find that resilient Spanish regions measured through evolutionary resilience methods also tend to be resilient when measured using ecological and engineering resilience methods. In other words, regions found to be resilient under evolutionary resilience were also likely to be found resilient under engineering and evolutionary resilience. The complementary nature of these interpretations should come as no surprise as the majority of RER definitions in literature implicitly highlight the ability of resilient regions to employ various types of resilience (Bristow & Healy, Citation2020; Davoudi et al., Citation2013; Hill et al., Citation2008; Martin, Citation2012; Wolman, Citation2017). For instance, Martin and Sunley (Citation2015, p. 13) provide a comprehensive definition of RER, noting:

the capacity of a regional or local economy to withstand or recover from market, competitive and environmental shocks to its developmental growth path, if necessary, by undergoing adaptive changes to its economic structures and its social and institutional arrangements, so as to maintain or restore its previous developmental path, or transit to a new sustainable path characterized by a fuller and more productive use of its physical, human and environmental resources.

4. TOWARDS A SYSTEM APPROACH

4.1. Forms of resilience

As mentioned, there are two forms of RER: performance and capacity. The former evaluates or appraises regions’ response to shocks (i.e., resistance, resilient and non-resilient), while the latter examines regional economies’ underlying adaptive capacity to respond to shocks (i.e., short-term and sudden disturbances) (Banica et al., Citation2020; Bristow & Healy, Citation2014; Evenhuis, Citation2017). Empirically, the resilience literature tends to focus on the performance aspect of RER (e.g., Foster, Citation2007; Hill et al., Citation2008; Sensier et al., Citation2016; Wolman, Citation2017), whereas resilience capacity has rarely been empirically examined. When the regions’ resilience capacity is examined, only qualitative approaches have been applied, such as case studies (Simmie & Martin, Citation2010; Wolfe, Citation2010), neglecting quantitative approaches.

It is important to examine capacity to identify the qualitative change that influences regions’ underlying adaptive capacity. Identifying the qualitative changes that affect RER is critical for informing regional policymaking and planning. Furthermore, it allows for an in-depth examination of why regional economies differ in resilience even though they may have either started with similar economic landscapes or implemented similar resilience strategies. Although examining regions’ resilience performance can inform regional policies and provide insight into the difference in RER, it does not provide an in-depth examination, generally providing quantitative overviews, such as regional differences in resilience. Also, the current approaches to examining RER through their performance typically employ a deterministic approach that starts by ascribing an interpretation of resilience that regions are then measured against. Examining RER by the qualitative changes provides a heuristic approach that indicates what type of resilience was employed. Additionally, as previously mentioned, the response of regions to shocks can shape their resilience to future shocks and influence their long-term growth and development (Crespo et al., Citation2017; Fingleton et al., Citation2012). Thus, examining the capacity of regions provides insight into why regions may be resilient to one shock but not the next and why regional economies experience a positive or negative hysteretic effect on their long-term growth trajectory following a shock. Overall, investigating the capacity of regions to shocks can guide research, advance the conceptual development of resilience, and inform regional policymaking and planning.

4.2. System approach

To investigate the resilience capacity of regions, this paper proposes a system approach, which presumes that regional economies, which are composed of economic actors, undergo system change (i.e., structural and functional change), or not, to employ different types of resilience. In other words, regional economies are composed of an array of economic actors (i.e., entrepreneurs, firms, industries and institutions) that determine regions’ overall resilience (Bristow & Healy, Citation2014). The system change that occurs when shocks hit regions directly reflects the economic activity produced by actors. Therefore, applying a system approach to RER results in the heuristic investigation of system change, rather than employing a deterministic approach that has traditionally been utilized empirically. Moreover, to undertake a system approach, indices (e.g., location quotient), descriptive statistics, such as data on industrial change at the NAICS two- or three-digit level, and other statistical tools can be employed to investigate and determine the system change that has occurred in a region or regions.

This approach does not neglect the multi-scalar factors (i.e., national policies, global production networks and international institutions) that affect economic activity but acknowledges that their influence either enhances or hinders economic actors’ ability to produce change. A system approach examines the qualitative change that occurs once economic actors have manoeuvred through the social, cultural, political and economic landscape of their region, which is shaped by multi-scalar influences.

The system approach promotes and focuses on the system change that occurs within a region(s) when hit by a shock(s). The complementary nature of the four types of resilience allows this approach to examine what type of resilience was employed and what system changes occurred, such as shifts in regions’ industrial structure from being highly specialized in the manufacturing industry to diversifying into the service sector or shifts in the function of industries into higher value-added industries, such as from traditional manufacturing to green technology manufacturing. It provides a novel analysis as it enables the examination of multiple shocks faced by regions and determines why regional resiliency changed or stayed constant between shocks. Currently, several studies that examine multiple shocks have only determined if regions’ resilience differed between shocks (e.g., Martin et al., Citation2016) but have not been able to explain why. The system approach, which employs indices, descriptive statistics, and other statistical tools, should be supplemented with other quantitative methods, such as statistical modelling, to indicate the region's resiliency, for which the system approach can provide a more in-depth analysis.

The required degree of system change – structures and functions – for each type of resilience varies, as illustrated in . First, for engineering resilience, a resilient regional economy bounces back to its pre-shock growth path after experiencing a shock while retaining its structure and function. Second, for ecological resilience, a resilient regional economy absorbs a shock and returns to its pre-shock growth path, which may require minor structural or functional change (Simmie & Martin, Citation2010). Third, for evolutionary resilience, a resilient regional economy undergoes varying degrees of structural and functional changes or adjustments to maintain its core performances, including employment, growth, and profitability (Faggian et al., Citation2018; Martin et al., Citation2016). Fourth, transformative RER implies that a region is resilient if it can create a new reconfiguration and set of structures and functions when a shock renders its economic system untenable (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020). As the literature on RER has implied (Dubé & Polèse, Citation2016), there are multiple possible post-shock growth paths that regional economies can develop in the short and long term. These potential growth paths depend on the system change regions will undergo to be resilient.

Table 2. Complementary nature of resilience and required system change.

These four types of resilience differ in the degree of system change required for regional economies to be resilient from shocks, ranging from no system change required (engineering resilience) to a complete reconfiguration of its structures and functions (transformative resilience).

Structural change refers to regions' industrial base and the type of industries that encompass them. In comparison, functional change refers to the functions of industries in a region. The ability of regional economies to undergo system changes in response to shocks depends on their adaptive capacity, which is the collective action and self-organization of economic actors or agents (i.e., entrepreneurs, firms and institutions). As noted by Bristow and Healy (Citation2014, p. 38), ‘[these] agents continually adapt their behaviour based on observations of the system as a whole or of others around them, through interactive mechanisms such as learning, imitation or evolution … to respond to changing conditions over time’. Therefore, the adaptive capacity of regions determines the resulting change to its economic system, if a change is needed, in the face of a shock, which subsequently determines if regions are resilient and what type of resilience regions employed (Bristow & Healy, Citation2020; Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Pike et al., Citation2010).

Further, regional economies can experience the same shock (i.e., recession) but experience heterogeneous impacts requiring different types of resilience. For example, one region, compared with the other, may be more adversely affected by the shock due to its industrial structure (i.e., a specialized economy in the auto industry) and, therefore, in order to be resilient, may have to undergo structural and functional change (evolutionary resilience). In contrast, the region, which has a different industrial structure (i.e., diversified economy), may not be adversely affected by the shock and thus, does not require any system change to be resilient but simply bounces back to its pre-growth path (engineering resilience).

To be resilient, regional economies need to employ different types of resilience depending on the type of shock experienced (Evenhuis, Citation2017) and its intensity and duration (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020). For instance, Evenhuis (Citation2017) notes that ecological resilience, which emphasizes resistance and recovery to shocks, may be more applicable for significant environmental disturbances like earthquakes and floods. Whereas evolutionary resilience, which emphasizes adaptability, may be more applicable for severe macroeconomic fluctuations, such as recessions. This is not to suggest a strict and rigid categorization of shocks and their required type of resilience, as regions will have heterogeneous responses to different shocks (Hu & Hassink, Citation2020; Pike et al., Citation2010), but at the risk of oversimplification, it is to demonstrate how different types of resilience may be more applicable to specific shocks (Evenhuis, Citation2017). Further, as shocks increase in intensity and duration, the required type of resilience also changes, starting with engineering resilience, which requires no structural adaptation and ending with transformative resilience, which requires complete, structural adaptation (Martin & Sunley, Citation2020).

System changes that occur, or do not occur, in regional economies in response to a shock – which subsequently determines the type of resilience that it employs and if regions are resilient – may or may not be the necessary system changes needed to be resilient. In fact, resilience may not always be a desirable action as it could result in regional economies being locked into less desirable growth paths that support outmoded and unproductive firms and industries (Martin & Sunley, Citation2017). Therefore, regions may employ evolutionary or transformative resilience that does not necessarily make them resilient in the short term, to the current shock that has hit their economy, but increases their long-term growth trajectory and their resilience to future shocks by reorienting their economy in the long term. In contrast, regions may employ engineering or ecological resilience that makes them resilient in the short-term, to the current shock that has hit their economy, but decreases their long-term growth trajectory and their resilience to future shocks by becoming locked-in to outmoded forms of production in the long term.

The system change approach, however, does not indicate if a region is actually resilient or not. Determining regions’ resilience to shock results from the examination of their resilience performance (Fingleton et al., Citation2012; Martin, Citation2012; Sensier et al., Citation2016). Specifically, the system change approach indicates the type of resilience that is employed in regions’ attempts to be resilient. This approach, therefore, should be used in combination with other quantitative methods to determine the resilience performance of regions. The advantage of using the system approach, in combination with performance measures, is that it allows researchers to identify how certain types of resilience influence their long-term growth and resilience to future shocks. For instance, a region that repeatably employs engineering or ecological resilience to shocks may eventually become locked-in to certain economic activity, reducing its long-run capacity to adapt, which may explain the region's non-resilient behaviour to future shocks and less favourable long-term growth trajectory. In contrast, a region that constantly employs’ evolutionary resilience may exhibit an increased adaptive capacity to global competitive pressures and be more likely to be resilient to future shocks and experience a more favourable long-term growth trajectory. Even further, a region that employs transformative resilience may exhibit a sudden shift to a more favourable long-term growth trajectory and experience increased adaptive capacity and thus, be more resilient to future shocks. This approach is particularly informative, given the greater access and availability of data to conduct long-term analysis of RER (e.g., Martin, Citation2012; Ray et al., Citation2017). Additionally, the system approach allows researchers to answer other questions that typically go unanswered when examining regions’ resilience performance. In particular, if a region is resistant, this does not tell us if the shock even hit the region or if it was hit and able to withstand the shock. If a region is resilient, this does not reveal what type of resilience was employed. Lastly, if a region is non-resilient, this does not provide information on why.

Another benefit of the system approach is that it allows researchers to answer more in-depth questions about resilience. That is, it allows researchers to answer questions such as: Resilience to what, for when, and for where (Meerow & Newell, Citation2019). First, as previously mentioned, the answer to the question ‘to what’ is shocks (i.e., short-term and sudden disturbance). If the answer is associated with long-term adaptability, then it risks losing its conceptual value, incorporating multiple interpretations. Second, the answer to the question ‘when?’ refers to the temporal focus of resilience, whether that focus is strictly on short-term recovery or enhancing regions’ resilience for the long term. It is hard to directly answer the ‘when?’ question as the temporal focus behind a collective and uncoordinated response to a shock is difficult to ascertain. However, the system approach can answer this question indirectly based on the type of resilience that is employed, with regions that employ engineering or ecological resilience being more or less content with short-term recoverability. In contrast, regions that employ an evolutionary or transformative resilience are more or less focused on the long-term robustness of their economy and thus, a greater concentration on the economies’ long-term resilience.

Third, the question ‘for where?’ focuses on the spatial aspect of resilience, highlighting that regional economies are nested in larger structures (i.e., multi-scalar), such as in national and supra-national economies (Meerow & Newell, Citation2019). In combination with other measures of resilience performance, a system approach can answer this question through a comparative analysis examining the types of resilience typically employed in different regions and subsequently assessing if they were resilient. For example, a comparative analysis can be conducted on rural and urban regions to determine if they differ in the type of resilience that they employ and their overall resilience to shocks. Further, a comparative study can assess the resilience of diversified and specialized economies or compare regions based on their specialization, such as those in high-tech industries compared with those in the manufacturing industries. The system approach can identify trends in resilience capacity between different regions. Overall, the system change can provide greater insight into pertinent questions revolving around resilience, especially regarding its spatial and temporal dimensions, providing a more informative answer through the incorporation of regions’ resilience capacity, which has largely been neglected.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This paper has advanced the resilience literature in several aspects. First, it provides a comprehensive overview of RER, explicitly highlighting the positive effects of shocks, the multi-scalar aspects of resilience, and the broad categories of shocks. Second, it provides a novel conceptual development of resilience, specifically regarding the complementary nature of the main types of resilience. Third, it developed a system approach to examining RER. In particular, it promotes the examination of regions’ capacity by investigating system changes (i.e., structural and functional) resulting from economic actors’ responses to shocks. This approach argues that the underlying and overall capacity of RER is determined by the economic actors that compose the region. In other words, system change in regions that result from their response to shocks is a direct reflection of the collective but uncoordinated economic activity produced by economic actors. Therefore, based on the developed complementary perspective of the main types of resilience, this paper demonstrates that through examining the system changes, research can determine the type of resilience regions employed during shocks.

A system approach is developed to promote and guide research in the heuristic examination of regions’ capacity, which has received little attention in the resilience literature, primarily focusing on regions’ resilience performance through deterministic approaches. The importance of a system approach is that it examines the system change resulting from shocks to provide a more in-depth examination of regions’ response to shocks. Also, this approach will help develop more robust resilience policies by informing regional policymaking and planning. Furthermore, this approach opens up new research avenues for understanding and investigating RER. For instance, this approach allows researchers to examine resilience capacity and performance simultaneously as well as explore what type of resilience contributes to more favourable long-term growth trajectories and greater resiliency to future shocks. Overall, this paper has advocated that future research should pay greater attention to the system changes that occur in regions during shocks.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors express their sincere thanks to Judith Sutton for her feedback on earlier versions of the paper. The authors are also grateful to the editor, Stephen Hincks, and three anonymous referees for their insightful and constructive comments that improved the final version of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2024.2310934)

Notes

1 For a more in-depth examination of each type of resilience origins, see Martin and Sunley (Citation2020).

REFERENCES

- Angulo, A. M., Mur, J., & Trívez, F. J. (2018). Measuring resilience to economic shocks: An application to Spain. The Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 349–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0815-8

- Banica, A., Kourtit, K., & Nijkamp, P. (2020). Natural disasters as a development opportunity: A spatial economic resilience interpretation. Review of Regional Research, 40(2), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10037-020-00141-8

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49(5), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Bristow, G. (2010). Resilient regions: Re-‘place’ing regional competitiveness. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp030

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2014). Regional resilience: an agency perspective. Regional Studies, 48(5), 923–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.854879

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2018). Innovation and regional economic resilience: An exploratory analysis. The Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0841-6

- Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2020). Handbook on regional economic resilience. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Brown, L., & Greenbaum, R. T. (2017). The role of industrial diversity in economic resilience: An empirical examination across 35 years. Urban Studies, 54(6), 1347–1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015624870

- Christopherson, S., Michie, J., & Tyler, P. (2010). Regional resilience: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq004

- Courvisanos, J., Jain, A., & Mardaneh, K. (2016). Economic resilience of regions under crises: A study of the Australian economy. Regional Studies, 50(4), 629–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1034669

- Crespo, J., Boschma, R., & Balland, P.A. (2017). Resilience, networks and competitiveness: A conceptual framework. In R. Huggins & P. Thompson (Eds.), Handbook of regions and competitiveness. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Davies, A., & Tonts, M. (2010). Economic diversity and regional socioeconomic performance: An empirical analysis of the Western Australian grain belt. Geographical Research, 48(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-5871.2009.00627.x

- Davoudi, S., Brooks, E., & Mehmood, A. (2013). Evolutionary resilience and strategies for climate adaptation. Planning Practice and Research, 28(3), 307–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2013.787695

- Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., Fünfgeld, H., McEvoy, D., Porter, L., & Davoudi, S. (2012). Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 299–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677124

- Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Towards the resilient region? Local Economy, 25(8), 650–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02690942.2010.533424

- Dicken, P. (2015). Global shift: Mapping the changing contours of the world economy (7th ed.). Guilford Press.

- Dubé, J., & Polèse, M. (2016). The view from a lucky country: Explaining the localised unemployment impacts of the great recession in Canada. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 9(1), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsv025

- Evenhuis, E. (2017). New directions in researching regional economic resilience and adaptation. Geography Compass, 11(11), e12333. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12333

- Faggian, A., Gemmiti, R., Jaquet, T., & Santini, I. (2018). Regional economic resilience: The experience of the Italian local labor systems. The Annals of Regional Science, 60(2), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-017-0822-9

- Fingleton, B., Garretsen, H., & Martin, R. (2012). Recessionary shocks and regional employment: Evidence on the resilience of UK regions. Journal of Regional Science, 52(1), 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00755.x

- Foster, K. A. (2007). A case study approach to understanding regional resilience. Working Paper 2007-08, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley. https://iurd.berkeley.edu/wp/2007-08.pdf.

- Hanley, N. (1998). Resilience in social and economic systems: A concept that fails the cost–benefit test? Environment and Development Economics, 3(2), 221–262. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355770X98250121

- Hassink, R. (2010). Regional resilience: A promising concept to explain differences in regional economic adaptability? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp033

- Hill, E., St. Clair, T., Wial, H., Wolman, H., Atkins, P., Blumenthal, P., Ficenec, S., & Friedhoff, A. (2012). Economic shocks and regional economic resilience. In M. Weir, P. Nancy, H. Wial, & H. Wolman (Eds.), Urban and regional policy and its effects (pp. 193–274). Brookings Institution Press.

- Hill, E., Wial, H., & Wolman, H. (2008). Exploring regional economic resilience. Working Paper 2008-06, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7fq4n2cv

- Holling, C. S. (1973). Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 4(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245

- Holm, J. R., & Østergaard, C. R. (2015). Regional employment growth, shocks and regional industrial resilience: A quantitative analysis of the Danish ICT sector. Regional Studies, 49(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.787159

- Hu, X., & Hassink, R. (2020). Adaptation, adaptability and regional economic resilience: A conceptual framework. In G. Bristow & A. Healy (Eds.), Handbook on regional economic resilience (pp. 54–68). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hudson, R. (2010). Resilient regions in an uncertain world: Wishful thinking or a practical reality? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp026

- MacKinnon, D., & Derickson, K. D. (2013). From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512454775

- Martin, R. (2012). Regional economic resilience, hysteresis and recessionary shocks. Journal of Economic Geography, 12(1), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbr019

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2015). On the notion of regional economic resilience: Conceptualization and explanation. Journal of Economic Geography, 15(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu015

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2017). Competitiveness and regional economic resilience. In R. Huggins & P. Thompson (Eds.), Handbook of regions and competitiveness: Contemporary theories and perspectives on economic development (pp. 287–307). Edward Elgar.

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2020). Regional economic resilience: Evolution and evaluation. In G. Bristow & A. Healy (Eds.), Handbook on regional economic resilience (pp.10-35). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Martin, R., Sunley, P., Gardiner, B., & Tyler, P. (2016). How regions react to recessions: Resilience and the role of economic structure. Regional Studies, 50(4), 561–585. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1136410

- Martin, R. L. (2018). Shocking aspects of regional development: Towards an economic geography of resilience. Oxford University Press.

- Meerow, S., & Newell, J. P. (2019). Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geography, 40(3), 309–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2016.1206395

- Modica, M., & Reggiani, A. (2015). Spatial economic resilience: Overview and perspectives. Networks and Spatial Economics, 15(2), 211–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11067-014-9261-7

- Olsson, L., Jerneck, A., Thoren, H., Persson, J., & O’Byrne, D. (2015). Why resilience is unappealing to social science: Theoretical and empirical investigations of the scientific use of resilience. Science Advances, 1(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1400217.

- Pendall, R., Foster, K. A., & Cowell, M. (2010). Resilience and regions: Building understanding of the metaphor. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp028

- Pike, A., Dawley, S., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq001

- Ray, D. M., MacLachlan, I., Lamarche, R., & Srinath, K. (2017). Economic shock and regional resilience: Continuity and change in Canada’s regional employment structure, 1987–2012. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(4), 952–973. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16681788

- Schumpeter, J. A. (2010). The process of creative destruction. In J. A. Schumpeter (Ed.), Capitalism, socialism and democracy (pp. 85–89). Routledge.

- Sensier, M., Bristow, G., & Healy, A. (2016). Measuring regional economic resilience across Europe: Operationalizing a complex concept. Spatial Economic Analysis, 11(2), 128–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17421772.2016.1129435

- Simmie, J., & Martin, R. (2010). The economic resilience of regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp029

- Swanstrom, T. (2008). Regional resilience: A critical examination of the ecological framework. Working Paper 2008-07, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkley. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9g27m5zg.

- Walker, B., Gunderson, L., Kinzig, A., Folke, C., Carpenter, S., & Schultz, L. (2006). A handful of heuristics and some propositions for understanding resilience in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 11(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-01530-110113

- Walker, B., Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S., & Kinzig, A. (2004). Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society, 9(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-00650-090205.

- Wolfe, D. A. (2010). The strategic management of core cities: Path dependence and economic adjustment in resilient regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsp032

- Wolman, H. (2017). Coping with adversity: Regional economic resilience and public policy. Cornell University Press.

- Zolli, A., & Healy, A. M. (2012). Resilience: Why things bounce back. Free Press.