ABSTRACT

Regions throughout the world are confronted with the challenge of restructuring their economies when existing growth paths decline. In regional strategies, directions are defined into which their economies shall be developed, thereby constituting a crucial moment for setting the course for future diversification. While considerable progress has been made in retrospectively understanding regional industrial path developments once these have emerged successfully, little attention has been paid to the processes by which regions develop strategies for future diversification. This article argues that in order to understand why a region aims to develop certain economic areas rather than others, this has to be seen in the context of the policymaking process. Based on a case study of the German lignite mining region ‘Rheinisches Revier’, the paper explores the role played by the configuration of regional policymaking processes, in which regions develop strategies, for the direction of these strategies. The findings highlight that regional strategies have to be understood as the product of a region-specific multi-actor process whose configuration affects the policy outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Regions throughout the world are confronted with different kinds of challenges ranging from increasing international competition through decarbonization to the digitalization of economic activities. In order to transform their economies according to such challenges, regions develop regional strategies in which they define areas of diversification that are to be promoted (most prominently the European Union’s (EU) Smart Specialisation Strategy – S3).

While substantial progress has been made in retrospectively understanding regional industrial path developments once they have emerged successfully (for an overview, see Boschma, Citation2017), surprisingly little attention has been dedicated to the processes by which regions develop strategies for diversification, in other words, how they aim to diversify their economies in the future. Only recently, since the introduction of the EU’s S3, an increasing number of studies started to investigate the implementation of these particular regional innovation strategies (Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation – RIS3) (e.g., Deegan et al., Citation2021; Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016; Marques & Morgan, Citation2021; Trippl et al., Citation2020). While this literature has generated highly valuable insights into implementation challenges in setting adequate priorities, the policymaking processes how a broader set of actors have shaped the strategy remain largely obscured. This is critical in order to fully understand why regions come up with a certain strategy or face implementation challenges, since regional strategy development is characterized as ‘wicked games’, most commonly distributed across heterogenous actors with differing interests (Benner, Citation2020a; Mäenpää & Lundström, Citation2018; Sotarauta, Citation2018). It can be argued that the direction of regional strategies is affected by the way the regional policymaking process is configured (Aranguren et al., Citation2016). Therefore, in order to fully understand why a region faces implementation challenges or aims to develop certain economic areas rather than others, this has to be seen in the context of the policymaking process, for example, which actors participated, how the actors interacted, etc.

Taking this as a point of departure, this article draws from an actor-centred institutionalism (ACI) approach to shed light on the role played by the configuration of regional policymaking processes, in which regions develop diversification strategies, for the direction of these strategies. This understanding is essential to avoid suboptimal solutions and to ensure the development of forward-looking transformation strategies. It also complements the predominant retrospective perspective on regional diversification by directing the attention toward the role of the decision-making processes that may at least partly shape the selection environment for regions’ future rounds of diversification. In this respect it seeks to address the largely neglected role of policymaking processes in research on regional path development (Uyarra et al., Citation2017; Uyarra & Flanagan, Citation2016).

To this end, the study explores (1) how the ‘Rheinisches Revier’ (RR) – a German lignite mining region – developed its regional transformation strategy and (2) what implications the configuration of this regional policymaking process has for the direction of the regional transformation strategy. Especially fossil mining regions are a group of regions that is confronted with the challenge to design forward-looking regional strategies to promote change and prepare for the decline or end of their often-dominant mining path in the next decades (see also Veldhuizen & Coenen, Citation2022). The RR provides a very topical case study because in 2019 the German government decided to phase out the lignite-based power generation by 2038. For the RR this means that a crucial regional development path will be eliminated. During the past years, the RR therefore developed a transformation strategy, termed the economic and structural program (Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramm – WSP), which specifies certain domains that are to guide the use of the structural funds provided by the German government. This topical status makes it possible to explore the processes and actors that have shaped the formulation of the strategy, a process that many other fossil mining regions in the world also have to undergo in the next decade and can learn from.

2. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK: REGIONAL STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT AND IMPLICATIONS FOR SETTING THE COURSE

Regional strategies, such as S3s or transformation strategies, outline the directions into which regions aim to develop their economies in the coming years. They define aims and domains that are to guide the use of public and private resources within the region. Therefore, they can be understood as decisive moments for a region’s industrial evolution. For instance, unrealistic aims, such as those apparent in the ‘Silicon Somewhere’ (Hospers, Citation2006), bear the risk of resources being misallocated and the new path development failing to succeed, while a strategy tailored solely to incumbents’ interests can increase the danger of a regional lock-in (Grabher, Citation1993).

Since the introduction of the EU’s S3 in the 2014–20 funding period, an increasing number of studies have generated valuable insights into the directions of RIS3 strategies (e.g., Deegan et al., Citation2021; Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016; Trippl et al., Citation2020). These point to various shortcomings in the setting of priorities by European regions. It has been revealed that some regions aim to develop economic domains that are not sufficiently embedded in the regional strengths (Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016). Moreover, some strategies suffer from a proliferation of priorities (Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Trippl et al., Citation2020). Overly broad strategies have been observed in particular in least-developed regions (Trippl et al., Citation2020) and in regions characterized by weaker institutional capacities (Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022). Further, some regions have been found to have difficulties in developing a forward-looking strategy due to their favouring the promotion of existing paths (Trippl et al., Citation2020). Deegan et al. (Citation2021) find that regions aim to develop economic domains related to regional structures, but these related domains are selected regardless of their attractiveness.

These non-optimal policy outcomes point to the fact that regional strategy development can hardly be understood as a mere technical exercise. Over the past few decades regional strategy development has shifted from a top-down to a bottom-up process that attempts to integrate a wide range of regional actors into the process. In so-called entrepreneurial discovery processes (EDP) firm and non-firm actors, such as universities or society, are mobilized in order to discover promising economic domains (Foray et al., Citation2012). Regional strategy development is thus ‘rarely the preserve of a single actor or group of actors: instead it is distributed across a multiplicity of actors’ (Uyarra & Flanagan, Citation2016, p. 317). It is a complex social and political process that involves the participation of actors with heterogenous interests and capabilities, as well as interactions between these actors (Aranguren et al., Citation2016; Benner, Citation2020a; Mäenpää & Lundström, Citation2018; Sotarauta, Citation2018).

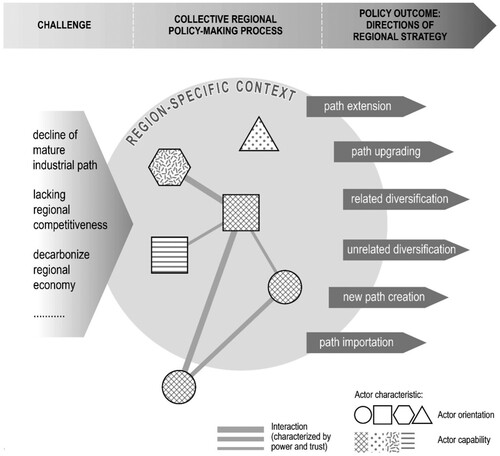

So, in order to explain why a specific region comes up with a certain kind of regional strategy that aims to promote particular economic areas rather than others we need to open up this policymaking process and assess its configuration, since this can shape the direction of the strategy. In the following, I therefore conceptualize regional strategies as the product of a region-specific multi-actor process whose configuration affects the policy outcomes defined in the strategy.

Looking at this collective policymaking process of developing a regional strategy from the perspective of an ACI approach (Scharpf, Citation1997) helps to take into account the involvement of heterogenous actors and their interactions in this process. The ACI approach has been developed by Scharpf and colleagues to analyse how policies were formulated and has also been applied to study regional governance arrangements in the last years (e.g., Döringer, Citation2020; Lintz, Citation2016). The ACI ‘conceptualizes policy processes driven by the interaction of … actors endowed with certain capabilities and specific cognitive and normative orientations, within a given institutional setting and within a given external situation’ (Scharpf, Citation1997, p. 37). The approach therefore emphasizes actors and actor constellations, interactions between actors as well as institutions. Actors are characterized by specific orientations (i.e., preferences) and capabilities that determine how they can shape the policy outcomes (Scharpf, Citation1997). The orientation refers to what policy outcomes an actor perceives as desirable or undesirable. Capabilities are understood as action resources (e.g., knowledge, physical capital, social capital) that determine actors’ ability to influence the policy outcome. Here, actors’ knowledge endowment constitutes a crucial actor capability that represents the rationale for implementing EDPs (Foray, Citation2016a; Hausmann & Rodrik, Citation2003). However, policy outcomes, such as Smart Specialisation priorities, are not the product of isolated individual actors’ actions, but also depend on interactions between the actors involved, as their preferences regarding the desirability of certain policy outcomes may match or conflict. Interactions like bargaining and blockade will most likely result in different policy outcomes than cooperative and facilitating interactions. The ACI considers that actors involved in policymaking processes operate in a setting of formal and informal institutions that affect both the actors’ actions and orientations, as well as their modes of interaction (Scharpf, Citation1997).

This last point already indicates that the characteristics involved in developing a regional strategy are also shaped by the region-specific context. There are further arguments for this regional influence (see also Aranguren et al., Citation2016; Trippl et al., Citation2020): First, a region’s economic structure affects the potential composition of actors that could be mobilized for the policymaking process (Trippl et al., Citation2020). It influences the capabilities and knowledge actors could introduce into the EDP. Second, institutional capacities for governing the development of a regional strategy differ across regions as they are subject to past experiences (Aranguren et al., Citation2016; Kroll, Citation2015). These differences can result in varying degrees of success in stakeholder involvement (Trippl et al., Citation2020). Third, interactions taking place in regional strategy development are not isolated from existing structures of social relations. Involved actors might share a joint history, for example, due to their participation in joint projects or regional networks. Regional policymaking processes are embedded in these structures (Granovetter, Citation1985). For instance, trust can facilitate knowledge exchange in the EDP (Boschma, Citation2005), it can also form the basis for coalition-building in the process of developing a regional strategy.

This regional dimension highlights the varying potential and challenges different types of regions are confronted with when developing a regional strategy. Fossil mining regions, for instance, are often characterized by a high industrial specialization in mature mining paths. This group of regions is therefore likely to face challenges when developing regional strategies for the future reorientation of the regional economy in at least two regards. First, a high specialization in a mature industry limits the possible actor composition and consequently the heterogeneity of actor capabilities that could be introduced into the EDP (Breul & Atienza, Citation2022; Breul & Nguyen, Citation2022). Second, ‘[r]egions with a dirty specialization [such as fossil mining regions] … face strong lock-ins due to the existing specialization. This implies that it will be difficult to mobilize actors for strategies that devaluate past investments’ (Grillitsch & Hansen, Citation2019, p. 2169), such as the development of green paths. Both challenges highlight how regional features are intertwined with the different conceptual components along the ACI framework.

Considering a regional strategy as the product of a process that is characterized by the components and influences presented above provides some indication as to the role played by the configuration of a regional policymaking process in terms of the direction of the regional strategy. ‘Depending on who is involved, what form of interactions take place between them, and how power dynamics are exercised among them, … the priorities a territory should target … will be different’ (Aranguren et al., Citation2016, p. 167). I will illustrate this influence based on two crucial steps in the process of developing a regional strategy for which the ACI provides a helpful lens in order to unpack their configuration and resulting consequences: discovery and priority setting.

First, it is necessary to discover promising economic fields. ‘It is a knowledge “of time and place”; this is local knowledge which is dispersed, decentralized, divided. It is hidden and needs to be discovered’ (Foray, Citation2016a, p. 10). The central idea of bottom-up processes like the EDP is to mobilize and combine this knowledge by bringing together a multitude of actors, for example, from the private sector, academia and society (Foray, Citation2016b).

The constellation of actors developing a regional strategy has a decisive influence on what opportunities can be identified because the opportunity space of discovering promising economic fields is actor-specific. Different actors identify different opportunities as they depend on actor capabilities and orientations (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). This means that failing to include actors from specific parts of the regional economy bears the risk of neglecting opportunities for future diversification. Likewise, an overrepresentation of certain groups of actors could lead to the potential of identified domains being overstated (Sotarauta, Citation2018). Different broadly defined actor types, such as incumbents, newcomers or extra-regional actors, tend to be attributed to different transformative potentials, and their presence or absence could lead to different directions of a regional strategy. While incumbents’ actor orientation is associated with reinforcing prevailing regional industrial structures (Neffke et al., Citation2018) (in regional strategy development this could mean promoting path extension), newcomers and extra-regional actors are associated with widening the opportunity space (Kyriakou, Citation2016; Neffke et al., Citation2018). The latter is needed for developing strategies that diverge from established regional development paths and promote change (e.g., new path creation, path importation). These elaborations highlight the value of applying an ACI lens in order to consider the role of varying actor capabilities and orientations in regional strategy development processes for final policy outcomes.

However, ideas tend not to be discovered and developed individually. Grillitsch underlines that ‘the process of entrepreneurial discovery requires the combination of different types of knowledge and resources, which are often held by actors belonging to different social groups’ (Grillitsch, Citation2016, pp. 28f.). This highlights the crucial role of interactions between different actors, as also put forward by the ACI approach (Scharpf, Citation1997), which can influence the outcome of the regional strategy development process. On the one hand, a lack of networks involving different groups of actors, and in a narrower sense a lack of trust, can impede the exchange of knowledge and collective learning in policymaking processes (Grillitsch, Citation2016; Klijn et al., Citation2010). Since new development paths but also the upgrading of existing paths tend to emerge from combining different types of knowledge, fragmented regional policymaking processes could reduce the probability of identifying these forward-looking new directions in the regional strategy (Grillitsch, Citation2016; see also Benner, Citation2020b). On the other hand, overly rigid networks run the risk that they ‘simply support the conservative behavior of actors bound to traditions and routines’ (Benz & Fuerst, Citation2002, p. 23). A common world view shaped by strong ties can lead to a denial of the need for reorientation and a glorification of present structures in the form of promoting path extension (e.g., Benner, Citation2020a; Grabher, Citation1993). These conditions are rather disadvantageous when attempting to identify domains that can be described as new path creation or path importation (see also Benner, Citation2020b).

Second, besides discovering promising economic fields, priorities have to be set in regional strategy development because ‘local government cannot address all potential specific capabilities and infrastructure needs for all new activities’ (Foray, Citation2016b, p. 1431). Selecting specific domains over others implies that actor orientations of some actors will be met by future funding while others will not. This highlights that regional strategy development is ‘an arena for discussions, battles and quarrels’ (Sotarauta, Citation2018, p. 197) and final policy outcomes must be regarded as the product of bargaining processes between the different actors as also conceptualized in the ACI approach (Scharpf, Citation1997).

In cases where actors have conflicting interests, the distribution of power is decisive for asserting their respective interests in the priority setting. Actors’ power position depends on actor capabilities, such as superior knowledge or social capital, as well as the institutional framework (Lintz, Citation2016). Two broad scenarios are possible – balance of power or domination (Grillitsch, Citation2016). When a balance of power prevails between actors that pursue conflicting interests in the priority setting, this can result in compromises or blockade (Grillitsch, Citation2016). Blockade can impede the problem-solving process (Scharpf, Citation1997) and threaten the development of a forward-looking regional strategy. In the case of domination, it is most likely that the dominating group of actors will assert their interests to the disadvantage of the dominated group (Grillitsch, Citation2016). Due to their historically grown strong embeddedness with the regional economy and institutions (Baumgartinger-Seiringer, Citation2021), especially the group of incumbent actors is likely to be capable of dominating in such a scenario. Generally speaking, incumbents are associated with preserving the status quo, leading to path extension rather than new path creation if this compromises the status quo.

However, conflict avoidance and the absence of negotiations can also bear the risk to come up with a non-selective strategy in which all actors’ expectations are met (see also Benner, Citation2020a). This kind of strategy contradicts the need to concentrate the use of scarce public resources on developing a limited number of promising areas. Summing up, these conceptual elaborations indicate how different configurations of the regional strategy development process are likely to result in different policy outcomes defined in the strategy. illustrates this link between the configuration of the policymaking process and the directions into which a region aims to develop. It highlights that regional strategies have to be understood as the product of a region-specific multi-actor process whose configuration affects the policy outcomes. The ACI lens, enriched through a regional dimension, is helpful in this regard because it allows to unpack these configurations ranging from actor capabilities and orientations to the particular mode of interaction that characterizes strategy development processes. In this understanding, an EDP is not just about how regional actors come up with ideas, but also how the broader set of actors (Sotarauta, Citation2018) as well as the region-specific context shape the strategy (Trippl et al., Citation2020). Thereby, the conceptual elaborations summarized in provide a framework that contributes to advance our understanding of the causes for the non-optimal policy outcomes observed in the growing body of research on S3s (e.g., Deegan et al., Citation2021; Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016; Trippl et al., Citation2020).

3. METHODS

The process by which the RR developed its regional strategy, the WSP, was analysed by means of process tracing. Process tracing is a well suited and commonly applied approach for reconstructing the trajectory of events that led to particular policy outcomes, including actor constellations and interactions between actors (e.g., Normann, Citation2017). In a first step, key events had to be identified (Scharpf, Citation1997). This was done (see section 4.1) on the basis of policy documents (ZRR, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021) and initial interviews with representatives of the network organization (ZRR) and its organizational nodes.

In a second step, information was gathered to study the characteristics of these key events in terms of the previously presented conceptual considerations. Semi-structured expert interviews have proved to provide suitable empirical access to information on the strategic processes, actors, and interactions that constitute regional strategy development (e.g., Faller, Citation2014). In total, thirteen expert interviews were conducted in German (for an overview, see ). Due to the pandemic situation, the interviews were conducted in the form of video conferences. In order to gather insights and perceptions from different angles of the strategy development process interviews were conducted with the organizing side as well as the participants’ side of the entrepreneurial discovery process. The former included interviews with the ZRR, a service company that assisted in the implementation of the process and representatives of the organizational nodes. Organizational nodes were created as decentralized organizational structure to support the ZRR in the mobilization of experts along the various future areas (FAs) of the WSP (see section 4). The organizational nodes consist of well-connected representatives (e.g., from the Chamber of Industry and Commerce) and organized the EDP for the respective FA. The participants’ side of the entrepreneurial discovery process included interviews with firms (automotive, energy technologies, metal fabrication), research facilities and local intermediaries like municipal business development agencies based on the criteria that they participated in the development process of the WSP. The interviewees were identified via desk research (e.g., documentations of workshops and project proposals) and snowball sampling. Based on the conceptual considerations made above, the semi-structured interview guideline included the topics of actor mobilization, actor constellation, idea discovery process, and priority setting. The qualitative data gained from the interviews were analysed in a systematic content analysis with a coding following the aforementioned categories. Throughout the empirical analysis we refer to the respective interviews by using the following codes: firm actors (F), local intermediaries (I), organizational nodes (O), research facilities (R), service provider assisting with the process implementation (S), ZRR (Z). Interview quotes were translated from German into English. These empirical insights were complemented on the basis of policy documents (ZRR, Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021).

Table 1. Number of interviews per type of respondent.

4. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS: REGIONAL STRATEGY DEVELOPMENT IN THE ‘RHEINISCHES REVIER’

The RR’s economy is characterized by lignite mining and lignite-fired power generation. In 2016, the lignite sector had an employment effect of 14,338 employees and accounted for a gross value added (GVA) of €1705 million (2.4% of the total regional GVA) when considering both direct and indirect effects (RWI, Citation2018). Moreover, energy-intensive industries in the RR are closely linked to the regional presence of the lignite sector as a cheap and reliable energy provider. The energy-intensive industries employed 93,000 persons (5.4% of the total regional employment) and generated €7.1 billion of GVA (29% of the regional GVA from the manufacturing sector) (Frontier Economics, Citation2018). Thus, the German government’s decision to phase out lignite production by 2038 implies the steady removal of a dominant regional growth path and presents the RR with the challenge of restructuring its economy. To this end, the RR developed a transition strategy, the WSP, which was first published in December 2019, with a refined version (WSP 1.1) published in April 2021. The WSP defines directions for the future restructuring of the region and aims to provide the content-related design for the funding envisaged by the government (ZRR, Citation2021).

The WSP is organized along four broad FAs: energy and industry, resources and agribusiness, innovation and education, space and infrastructure (see Table A1 in Appendix A). Each of these FAs encompasses various areas of action (AoA). In total, the WSP includes 21 AoAs which have varying degrees of concretization ranging from specific fields, like the production of solar cells, to broadly defined fields like energy-efficient and climate-neutral production. Moreover, the AoAs include horizontal (sector-neutral) measures, such as supporting entrepreneurs or digitalizing production, and vertical measures that focus on the promotion of a particular technology or industry. These include the hydrogen industry, the manufacture of solar cells, the manufacture of battery and fuel cells, aviation industry, biotech, among others.

All in all, this regional strategy can therefore be characterized as very comprehensive, both in terms of defining broad topics that provide wide scope for interpretation, and in terms of the multiplicity of domains. Furthermore, the strategy includes the promotion of different types of regional industrial path development. On the one hand, the WSP includes AoAs that aim to develop new paths (e.g., the hydrogen industry, the manufacture of battery and fuel cells). On the other hand, other AoAs focus on path upgrading (e.g., resource efficiency and circular economy, digitalizing production). Thus, the WSP takes into consideration both the modernization of existing economic activities as well as expanding the existing regional economy by promoting the development of new growth paths. Signs of a regional lock-in due to an overly strong focus on path extension are not discernible.

In the remainder of this paper the process by which these policy outcomes were developed is analysed. To this end, section 4.1 reveals in a first step the characteristics of how the WSP was developed. These provide the context for understanding certain policy outcomes defined in the regional strategy. The presentation of the empirics is organized along three subsections that follow the conceptual elaborations. Building on this empirical base, section 4.2 then discusses the implications of the configuration of the policymaking process for the direction of the WSP.

4.1. Developing the WSP

In June 2018 the German government assigned the Commission on Growth, Structural Change and Employment (CGSE) to design a coal phase-out that would balance various interests. The commission’s final report, published in January 2019, recommended an entire phase-out by 2038. The report served as a basis for the Act to Reduce and End Coal-Fired Power Generation and the Structural Development Act which were passed in July 2020 (BMWi, Citation2022). These developments forced the RR to develop its regional strategy in a relatively rapid process that can be divided into three broad phases ().

Table 2. Milestones of the regional strategy development in the ‘Rheinisches Revier’.

First, at the same time as the start of the CGSE in June 2018, various key actors of the RR decided during an annual event in Cologne to position the region in the context of the national lignite phase-out in order to ensure that the region would benefit from any structural funding. This can be seen as the initial spark that triggered the development of the regional transformation strategy. The outcome of this meeting was a position paper released in September 2018 in which the RR ‘prepared for the commission’ (Z1) by outlining the need for structural funding and explaining how it would be used (ZRR, Citation2018). The four FAs were defined in the position paper for the first time (Z1, S1).

Second, in September 2019 a kick-off conference heralded the development of the WSP 1.0, which was released in December 2019. During this short period the content of the four FAs defined in the position paper was concretized: ‘the bones were there and the flesh around them was missing and that was then added accordingly during this time’ (Z1). The content for each FA was developed by individual ‘organizational nodes’. In October 2019 each organizational node held up to two events in which regional experts were integrated into the process in order to develop the content for the particular FA (ZRR, Citation2019).

Third, during summer 2020 different events were conducted for public participation, ranging from online exchange platforms to mobile information booths. Statements made by different public interest parties were also included. Based on this, revisions were made and the WSP 1.1 was published in April 2021. However, the revisions led mainly to changes in regard to the structure, not the content (O1, O2, O3).

4.1.1. Mobilization

The WSP was developed in a collective regional policymaking process: ‘the region should see for itself what is good for [its future development] and not get it from Düsseldorf or from Berlin or from Brussels’ (Z1). To this end, the Zukunftagentur Rheinisches Revier (ZRR), as a network organization for the RR, was instructed by the Ministry for Economic Affairs of the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia (MWIDE NRW) to develop the regional strategy jointly with regional actors. Furthermore, so-called ‘organizational nodes’ were created for each FA. These had the purpose to mobilize the relevant regional experts in the particular fields and bundle the expertise and ideas of the RR. While being decentralized located at other established regional organizations, such as the Chamber of Industry and Commerce, the organizational nodes are affiliated as branches to the ZRR (ZRR, Citation2021).

As outlined in section 2, to understand the outcomes of the regional strategy development process it is crucial to consider the extent to which a broad range of actors could be mobilized and integrated into the EDP. In the first phase (Citation2018) the regional managements in the RR organized a call for ideas to mobilize regional actors and collect first ideas to fill the FAs in the position paper with content (S1, Z1). In this early phase in 2018, the call for ideas was organized by the regional managements, since organizational nodes did not yet exist. However, the three regional managements interpreted the call differently and therefore chose different ways to organize the call in their respective territory, leading to spatially uneven participation rates across the RR:

the city region of Aachen … already formulated very clearly at that time: ‘Tell us about projects that you would like to realize in the near future.’ While the Cologne/Bonn region was very cautious and said they were not making a call for projects yet, because they did not yet know how a qualification and selection process would take place later. [Therefore they] would name some illustrative examples that exist. That’s why there was such a huge disparity in the Cologne/Bonn region, further east [in the Cologne/Bonn region] there were only individual points that were exemplary, towards Aachen there was an enormous number of project points. (S1)

By and large, the interviewees confirmed that an EDP had taken place that was able to include a broad range of actors ranging from academia to public authorities and the private sector. For instance, 500 persons from different areas participated in the kick-off conference in September 2019. Also, subsequent expert events in October and November 2019 organized by the organizational nodes mobilized a multiplicity of regional experts (e.g., 200 participants at the event organized by the organizational node for energy and industry) (ZRR, Citation2019; O2). Generally, interviewees perceived the EDP as open to anyone interested in participating (R2, O1). In regard to the actor constellation, no official participation lists are available due to non-disclosure. However, interviewees reported that especially research facilities were overrepresented, while corporate actors were underrepresented (S1, F1, O2, O4). This was noted in particular for SMEs and start-ups (F1, O4). One corporate interviewee ‘found it striking that very few companies were there. … there were over 150 of us, but I felt there were few companies. I was sometimes the only one with 3–4 people’ (F1). A representative of one of the organizational nodes explained that SMEs are ‘a group that is difficult to address and also to mobilize for this process’ (O4). There are different explanations for the difficulty in mobilizing firms. First, participation in such a policymaking process is time-consuming and companies lack the time resources to actively engage in the process over longer periods of time (F1, I2). Second, the direct benefit of participation is called into question by some companies (O2). Therefore, intermediaries such as municipal development agencies played a crucial role in ensuring the introduction of local knowledge by representing the ideas and interests of local economic actors (F1, O4, I1).

In addition, the process was basically also open to actors from outside the region. To give an example, the idea to develop a carbon-free paper production in the RR was introduced by the German Paper Mills Association and in close cooperation with actors from other German regions, like the Technical University of Darmstadt, where relevant knowledge production takes place (I1).

4.1.2. Idea development process

Besides mobilizing regional actors, it is crucial to consider how firms, research institutes, and other actors developed and integrated ideas into the strategy development process. The expert events held by the respective organizational nodes between September and November 2019 served as the main arena for collecting ideas and developing the content of the various FAs. Responses from the interviewees, both firm actors, research institutes as well as local intermediaries indicate that ideas were generally not developed within these workshops, but already existed beforehand (F1, F2, F3, I1, I2, R1). For instance, the EDP benefited from strategies already existing in subregions (e.g., Reload 2030, Rhein-Erft-Kreis; industry initiative, Düren) that had been developed separately prior to the lignite phase-out and could then be introduced by the respective business development agencies into the development process of the WSP (F1, I1). Representatives of companies and research institutes also explained that the ideas had already existed beforehand and the context of the structural change and the WSP provided a window of opportunity to pursue these ideas and introduce them in the expert events between September and November 2019 (F1, F2, F3, R1).

While interacting with other organizations has been reported as important for developing the ideas (e.g., fuel cell production, digitalized and low-emission textile manufacturing), the finding highlights that these interactions took place prior to the actual strategy development process and relied on existing networks. Nonetheless, the events held by the organizational nodes were perceived as important networking opportunities for future cooperation. For instance, in some cases project partners for subsequent project application phases were found there (O4, F1, R2). It suggests that the development process of the WSP has generated impulses for intensifying interactions across the various parts of the RR’s regional innovation system. Moreover, the potential of connecting different actor groups across the RR was acknowledged by the ZRR and the organizational nodes and is to be fostered in future discovery processes in order to identify ‘cross innovation, that is, when you combine previously unrelated or not linked sectors with each other’ (O4).

The ideas developed by the interviewees build on existing capacities and activities and are not made up from the scratch (R1, R2, F1, F3, O3, I1). For instance, a research institute that has competences in upscaling production developed the idea to apply this knowledge to the area of manufacturing fuel cells (R1). Another example is an aluminium producer that developed the idea of integrating recycled components from other areas into the aluminium industry in order to create a circular aluminium production (F3).

4.1.3. Priority setting

As revealed above, the EDP in the RR mobilized a large number of regional actors with a broad range of ideas for the future orientation of the RR (see Table 1 in Appendix A for a full list with AoA). But which ideas were selected for integration into the WSP? The ZRR formulated broad criteria. Domains were required to contribute to job creation and a more sustainable development, and build on existing regional capabilities (Z1, I1). Besides complying with these rather broad criteria or the fact that some topics such as specific educational programs were taking place at higher spatial levels of jurisdiction (O4), no clear selection of domains occurred:

So I’m not aware of anything being suggested anywhere as a potential or as a field of action that was then not taken into account. (O2)

Actually, nothing was thrown away in that sense, nope. (R2)

4.2. Implications of the configuration of the WSP development process

The previous section revealed characteristics of how the WSP was developed. These provide the context for understanding certain policy outcomes defined in the regional strategy. This section discusses the implications of the configuration of the policymaking process for the direction of the WSP.

First, the development of the WSP was subject to a complex EDP that involved a large number of actors. The EDP was able to benefit from the availability of a critical mass of capable actors in the RR, existing networks, and institutional capabilities and preliminaries for stakeholder involvement as is also observed in other regions with organizationally thick and diversified regional innovation systems (Trippl et al., Citation2020). ‘There were an incredible number of people, many project ideas. … This also shows what a tremendous potential there already is in the entire region’ (F1).

Although the EDP was characterized by an unbalanced representation of different stakeholder groups, it can still be described as relatively open, so that different actor groups were able to participate in the process and introduce knowledge from their opportunity spaces. This allowed the development of an overall broad focus that promoted different types of path developments defined in the WSP (see Table 1 in Appendix A). Especially through the involvement of incumbents, such as firms from energy-intensive industries, ideas for promoting path upgrading are prominent aims in the WSP, that is, ‘that I maintain what I have and that I improve it in the direction that society wants it to go’ (F3). Examples are the transformation of aluminium production to circular production, the diversification of automotive suppliers towards e-mobility or digitalizing and greening textile production (F3, I1, R2).

Particularly by involving actors from the field of science, ideas for promoting new industrial paths were defined in the WSP, such as transforming existing scientific knowledge into the manufacture of fuel cells (R1). At the same time, however, some interviewees expressed concerns that the involvement of large numbers of actors from science could lead to a strategy orientation that does not necessarily translate into the type of regional economic outcomes needed to cope with the structural change: ‘Indirectly, of course, one also benefits from the scientific know-how, but a Research Centre Jülich or a RWTH Aachen University, is not per se positioned in such a way that it always wants to generate effects for the region’ (S1).

The analysis of the idea development process indicated that ideas were largely developed based on existing regional capabilities. This feature led to a strategy in which domains are rooted in existing regional capabilities, which is highlighted throughout the WSP (ZRR, Citation2021). This place-based strategy development prevented the emergence of what Balland et al. (Citation2019) term a ‘casino policy’, which aims to promote completely new economic fields from scratch and has a high probability of failure due to a lack of the preconditions that could support its realization.

Furthermore, the analysis indicated the crucial role of local intermediaries for mobilizing and representing ideas of local firms in the EDP. This feature suggests a subregion-specific character of the EDP, since institutional capacities are likely to differ across the RR.

It always depends on whether the municipalities really have an economic development agency or whether they are so small that they can’t afford something like that. So [the representation of local companies in the WSP development process] is partly what happened in Eschweiler or Jülich, but not now in Titz. (I1)

This leads to another crucial feature of the strategy development process – the largely missing priority setting. As a consequence, the WSP can be characterized as a very comprehensive, non-selective regional strategy encompassing a large number of domains (21 AoAs; see Table 1 in Appendix A). Representatives of the ZRR state that it basically allows almost any kind of project funding (O2, O3, Z1), as illustratively explained in this quote: ‘only projects that somehow fit into the WSP can be funded. But it’s so broad … , actually everything fits in there, as long as it’s not a new coal-fired power plant, and that’s why I think it’s always possible’ (O3) Therefore, no tensions and conflicts such as in the form of blockades have shaped the strategy development process, because the lack of prioritization did not turn some participants into potential beneficiaries of future funding while excluding others. Of course, there is a political rationale behind a broad strategy that represents all the different interests of stakeholders in the region (Foray, Citation2016a). However, the literature on Smart Specialisation emphasizes that a selection of domains is inevitable. First, there is a need to concentrate limited public funding to few areas. Second, administrative and technical capacities are restricted and cannot efficiently address the needs of a large number of different areas (Foray, Citation2016b; Gianelle et al., Citation2020). The difficulties involved in setting priorities and developing a focused regional strategy has also been noticed in the context of various Smart Specialisation strategies (e.g., Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Trippl et al., Citation2020).

At the same time, the lack of prioritization also indicates that little or no influence of a top-down mode of planning has occurred. As is known from the long history of top-down priority setting, top-down influences entail the risk of policy capture, picking winners as well as anti-competitive effects (e.g., Foray, Citation2016b). Due to the absence of top-down priority setting, the WSP provides a significant degree of openness for very different economic dynamics to unfold in the RR in the coming years. In the end, the scope and type of dynamics that unfold will depend on the allocation practice of the funding. Moreover, since there was no clear selection process, the thematic orientation of the regional strategy was less prone to distortions by dominating actor groups asserting their interests to the detriment of the ideas of the dominated groups. Therefore, proposals from different interest groups, e.g., incumbents and niche actors, remain included in the strategy. These considerations highlight the challenges associated with selective and non-selective regional strategies.

5. CONCLUSIONS

Especially fossil-energy producing regions like the RR, but also various other types of regions throughout the world, are faced with the challenge of restructuring their economies due to the cessation of dominant regional growth paths. In regional strategies, regions define the direction into which their economies are to be developed, thereby setting the course for future diversification. This article argued that in order to fully understand the direction of a regional strategy, it has to be seen in the context of the policymaking process. The study therefore set out to explore the role of the configuration of regional policymaking processes, by which regions develop strategies, for the direction of these strategies. To this end, the article proposes a framework that allows to unpack the characteristics of regional strategy development processes and link them to the policy outcomes. The framework is applied to the development of the WSP in the RR to illustrate the value of understanding regional strategies as the product of a region-specific multi-actor process whose configuration affects their direction. The case study on the RR reveals that the WSP is the product of a dense EDP, in which a large number of different actors was involved in order to find ideas for the future restructuring of the RR’s economy. The results show that ideas generally already existed and the EDP served as the window of opportunity to introduce the ideas into the strategy, rather than as a platform for idea development. The findings therefore stress the importance of existing economic structures, institutional capabilities on lower geographical scales (e.g., municipal economic development agencies) and existing networks for mobilizing actors and discovering ideas. In this regard, the WSP development process benefited from a sophisticated regional setting consisting of a critical mass of actors from a diversified industrial context (for more details on the diversified industrial context of the RR and its diversification potential, see Breul, Citation2022) as well as experienced institutional actors. As a result of this open process, a wide spectrum of domains was identified and defined in the WSP that definitely made it possible to go beyond a one-sided focus on safeguarding the existing activities of a specific regional actor group. AoAs range from promoting the upgrading of existing economic structures to creating new economic activities. A noteworthy illustration of how the configuration of the regional policymaking process affected the policy outcome is the absence of a clear priority setting of domains. This resulted in a non-selective regional strategy that is ‘as wide as possible and as open as possible’ (O2). While it prevented the risk of powerful actors dominating the process in favour of their interests or policy failure to pick the winner, the non-selective regional strategy entails the risk of distributing the scarce funds to too many areas as was also criticized in other regional contexts (e.g., Gianelle et al., Citation2020). While regional lock-ins have been thematized most prominently as major obstacle for designing forward-looking transformation strategies in highly specialized regions (Campbell & Coenen, Citation2017; Grabher, Citation1993), the case study of the RR shows that even when this major challenge has been overcome (e.g., through a definite phase-out) there are other challenges that need to be considered when setting the course for future diversification. For policy practitioners these findings highlight the need to be wary in terms of how to design the development process of regional strategies. A different design will likely lead to different outcomes with implications for future diversification.

On a conceptual level, the article contributes to the growing body of research on S3s by providing a framework that allows to unpack the processes by which regions develop their strategies, taking an important step towards studying the causes for the non-optimal policy outcomes observed in recent studies (e.g., Deegan et al., Citation2021; Di Cataldo et al., Citation2022; Gianelle et al., Citation2020; Iacobucci & Guzzini, Citation2016; Trippl et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, for research on regional diversification and industrial path development the study shows ways how to integrate and acknowledge the role of policymaking processes in order to fully understand the industrial evolution of regions (see also Uyarra et al., Citation2017; Uyarra & Flanagan, Citation2016). The framework proposed in this article allows to consider the ‘middle ground between narrow firm-led regional branching approaches and a heroic view of policy actors endowed with all the necessary oversight and competences’ (Uyarra & Flanagan, Citation2016, p. 318) by shifting the focus towards the collective and multi-actor nature of contemporary policymaking. This focus on unpacking and understanding regional strategy development can complement the predominant retrospective view on regional diversification (Boschma, Citation2017) by directing attention towards the role of the policymaking process that may at least partly shape the selection environment for regions’ future rounds of diversification or lack thereof. Instead of examining how regions diversified retrospectively, asking how they aim to diversify and how these strategy orientations are created provides a forward-looking perspective on the conditions under which the course was set for future path development. It provides insights into why one certain path was promoted rather than another, why some regions prefer to promote mature paths and others fail to select the most promising options and instead distribute the scarce funds indiscriminately. These are the insights needed to design regional strategy development processes in a way that avoids backward-looking interests dominated by vested interests.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Aranguren, M. J., Navarro, M., & Wilson, J. R. (2016). From plan to process: Exploring the human element in smart specialisation governance. In P. McCann, F. van Oort, & J. Goddard (Eds.), The empirical and institutional dimensions of smart specialisation (pp. 165–189). Routledge.

- Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Crespo, J., & Rigby, D. L. (2019). Smart specialization policy in the European union: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1252–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1437900

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S. (2021). The role of powerful incumbent firms: shaping regional industrial path development through change and maintenance agency (Papers in Economic Geography and Innovation Studies 2021/07).

- Benner, M. (2020a). Mitigating human agency in regional development: The behavioural side of policy processes. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 164–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1760732

- Benner, M. (2020b). The spatial evolution–institution link and its challenges for regional policy. European Planning Studies, 28(12), 2428–2446. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1698520

- Benz, A., & Fuerst, D. (2002). Policy learning in regional networks. European Urban and Regional Studies, 9(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.15488/3038

- BMWi. (2022). Kohleausstieg und Strukturwandel. https://www.bmwi.de/Redaktion/DE/Artikel/Wirtschaft/kohleausstieg-und-strukturwandel.html.

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Breul, M. (2022). Strukturwandel im rheinischen revier: Eine analyse der technologischen diversifizierungspotenziale. Standort, 46(2), 84–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00548-022-00773-7

- Breul, M., & Atienza, M. (2022). Extractive industries and regional diversification: A multidimensional framework for diversification in mining regions. The Extractive Industries and Society, 101125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2022.101125

- Breul, M., & Nguyen, T. X. T. (2022). The impact of extractive industries on regional diversification – evidence from Vietnam. The Extractive Industries and Society, 100982. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2021.100982

- Campbell, S., & Coenen, L. (2017). Transitioning beyond coal: Lessons from the structural renewal of Europe’s old industrial regions. CCEP Working Paper: Vol. 1709.

- Deegan, J., Broekel, T., & Fitjar, R. D. (2021). Searching through the haystack: The relatedness and complexity of priorities in smart specialization strategies. Economic Geography, 97(5), 497–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1967739

- Di Cataldo, M., Monastiriotis, V., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2022). How ‘smart’ Are smart specialization strategies? JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 1272–1298. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13156

- Döringer, S. (2020). Individual agency and socio-spatial change in regional development: Conceptualizing governance entrepreneurship. Geography Compass, 14(5), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12486

- Faller, F. (2014). Regional strategies for renewable energies: Development processes in greater Manchester. European Planning Studies, 22(5), 889–908. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.741572

- Foray, D. (2016a). The concept of the ‘entrepreneurial discovery process. In D. Kyriakou (Ed.), Governing smart specialisation (pp. 5–19). Routledge.

- Foray, D. (2016b). On the policy space of smart specialization strategies. European Planning Studies, 24(8), 1428–1437. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1176126

- Foray, D., Goddard, J[J], Goenaga Beldarrain, X., Landabaso, M., McCann, P[P], Morgan, K[K], Nauwelaers, C., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2012). Guide on Research and Innovation Strategies for Smart Specialisation. European Commission. https://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/en/w/guide-on-research-and-innovation-strategies-for-smart-specialisation-ris3-guide-.

- Frontier Economics. (2018). Die bedeutung des wertschöpfungsfaktors energie in den regionen Aachen, Köln und Mittlerer Niederrhein. Kurzstudie im Auftrag von IHK Aachen, IHK Köln und IHK Mittlerer Niederrhein. https://www.frontier-economics.com/media/2238/die-bedeutung-des-wertschopfungsfaktors-energie-den-regionen-aachen-koln-und-mittlerer-niederrhein.pdf

- Gianelle, C., Guzzo, F., & Mieszkowski, K. (2020). Smart specialisation: What gets lost in translation from concept to practice? Regional Studies, 54(10), 1377–1388. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1607970

- Grabher, G. (1993). The weakness of strong ties: The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area. In G. Grabher (Ed.), The weakness of strong ties. The lock-in of regional development in the Ruhr area (pp. 255–277). Routledge.

- Granovetter, M. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481–510. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2780199. doi:10.1086/228311

- Grillitsch, M. (2016). Institutions, smart specialisation dynamics and policy. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 34(1), 22–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263774X15614694

- Grillitsch, M., & Hansen, T. (2019). Green industry development in different types of regions. European Planning Studies, 27(11), 2163–2183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1648385

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). TRinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hausmann, R., & Rodrik, D. (2003). Economic development as self-discovery. Journal of Development Economics, 72(2), 603–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00124-X

- Hospers, G–J. (2006). Silicon somewhere? Policy Studies, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870500499934

- Iacobucci, D., & Guzzini, E. (2016). Relatedness and connectivity in technological domains: Missing links in S3 design and implementation. European Planning Studies, 24(8), 1511–1526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1170108

- Klijn, E–H, Edelenbos, J., & Steijn, B. (2010). Trust in governance networks. Administration & Society, 42(2), 193–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399710362716

- Kroll, H. (2015). Efforts to implement smart specialization in practice—leading unlike horses to the water. European Planning Studies, 23(10), 2079–2098. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.1003036

- Kyriakou, D. (2016). Governing smart specialisation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315617374

- Lintz, G. (2016). A conceptual framework for analysing inter-municipal cooperation on the environment. Regional Studies, 50(6), 956–970. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2015.1020776

- Marques, P., & Morgan, K. [. (2021). Getting to Denmark: The dialectic of governance & development in the European periphery. Applied Geography, 135, 102536, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apgeog.2021.102536

- Mäenpää, A., & Lundström, N. (2018). Entrepreneurial discovery processes through a wicked game approach. In Å Mariussen, S. Virkkala, H. Finne, & T. M. Aasen (Eds.), Regions and cities. The entrepreneurial discovery process and regional development: New knowledge emergence, conversion and exploitation (pp. 74–91). Routledge.

- Neffke, F., Hartog, M., Boschma, R., & Henning, M. (2018). Agents of structural change: The role of firms and entrepreneurs in regional diversification. Economic Geography, 94(1), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2017.1391691

- Normann, H. E. (2017). Policy networks in energy transitions: The cases of carbon capture and storage and offshore wind in Norway. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118, 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.02.004

- RWI. (2018). Strukturdaten für die Kommission ‘Wachstum, Strukturwandel und Beschäftigung’: Projektbericht für das Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi): Projektnummer: 21/18. RWI – Leibniz-Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung. http://hdl.handle.net/10419/202065.

- Scharpf, F. W. (1997). Games real actors play: Actor-centered institutionalism in policy research. Theoretical lenses on public policy. Westview Press. http://www.loc.gov/catdir/enhancements/fy0832/97016122-b.html.

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Trippl, M., Zukauskaite, E., & Healy, A. (2020). Shaping smart specialization: The role of place-specific factors in advanced, intermediate and less-developed European regions. Regional Studies, 54(10), 1328–1340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1582763

- Uyarra, E., & Flanagan, K. (2016). Revisiting the role of policy in regional innovation systems. In R. Shearmu, C. Carrincazeaux, & D. Doloreux (Eds.), Handbook on the geographies of innovation (pp. 309–321). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784710774.00034

- Uyarra, E., Flanagan, K., Magro, E., Wilson, J. R., & Sotarauta, M. (2017). Understanding regional innovation policy dynamics: Actors, agency and learning. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(4), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654417705914

- Veldhuizen, C., & Coenen, L. (2022). Smart specialization in Australia: Between policy mobility and regional experimentalism? Economic Geography, 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2022.2032637

- ZRR. (2018). Das Rheinische Zukunftsrevier. Eckpunkte eines Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramms. https://www.rheinisches-revier.de/media/20181012_eckpunkte_strukturprogramm_rheinisches_zukunftsrevier_kleinere_aufloesung_1.pdf.

- ZRR. (2019). Das Making-Of des Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramms für das Rheinische Zukunftsrevier 1.0. https://www.rheinisches-revier.de/media/191211_making_of_fachkonf_revierknoten_klein.pdf.

- ZRR. (2020). Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramm für das Rheinische Zukunftsrevier 1.0. https://www.rheinisches-revier.de/media/wsp_1-0_web.pdf.

- ZRR. (2021). Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramm 1.1 für das Rheinische Zukunftsrevier. https://www.rheinisches-revier.de/media/210426_wsp_1_1_webversion.pdf.

APPENDIX A

Table A1. Content of the Wirtschafts- und Strukturprogramm (WSP).