ABSTRACT

This study analyses the knowledge-sharing process and its outcomes among stakeholders (i.e., academia, industry, government and civil society) in the context of a regional sustainability-oriented project held in Ena City, central Japan, by using the Quadruple Helix (QH) framework. We collected data through interviews with the stakeholders and related documents and employed qualitative content analysis to analyse the data. Our findings imply that there is a gap between the theoretical understanding and practical application of sustainability practices at the initial stage of interaction. However, the project facilitated inter-exchanges of knowledge among stakeholders in the respective helices that could address this gap. Our research suggested the roles of stakeholders in a sustainability-driven collaboration as bridging academics, resource-providing industry, observant government and boundary-spanning civil society which represent the balanced QH model. The current study contributes to the existing literature three-fold. First, few existing studies have employed the QH model in the context of sustainability. Second, most previous studies on the QH model have focused on macro-perspectives. Third, the study clarifies the roles of the stakeholders, which extends the understanding of the QH model. This study suggests a regional sustainability policy that encourages more bottom-up initiatives, in line with the balanced helix model.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sustainability has become a universal call of action for every legitimate organization since the adoption of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) during the 2015 United Nations General Assembly (United Nations, Citation2015). The SDG 17 for partnerships suggests that knowledge-sharing among community members is crucial in enabling collaboration and developing new ideas to solve social problems (Cummings, Citation2004). Organizations need to emphasize and more effectively exploit knowledge-based resources that already exist within and beyond their existing environment through social and community networks to address the needs of relevant members for sustainability in local settings (Cross & Cummings, Citation2004; Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998). Globalization has also transformed the roles of knowledge and innovation in the sustainable development of any economy (Galvao et al., Citation2019). Numerous recent studies explained the importance of knowledge-sharing in enhancing sustainability through developing the innovation system in regional contexts, with stakeholders playing a key role in the process (Gouvea et al., Citation2013; Hasche et al., Citation2020; Roman et al., Citation2020; Yun & Liu, Citation2019). Geographical proximity is also an important factor to consider in the knowledge-sharing process because the knowledge transfer between key actors in the innovation processes is difficult to perform outside of the regional or territorial boundaries.

The Triple Helix (TH) model has been widely used as a popular framework to help create, share and transfer knowledge for innovation among regional stakeholders, namely governments, industries and universities (Gouvea et al., Citation2013; Hasche et al., Citation2020; Schoonmaker & Carayannis, Citation2013; Yun & Liu, Citation2019). However, the model has been shown to be ineffective as there are cases of regional developments that do not exhibit a sufficient degree of knowledge transfer in the innovation process (Miller et al., Citation2018). Kimatu (Citation2016) noted that the evolution of the interactions of the innovation models has increasingly raised the necessity of the roles of civil society, which have been increasingly important in sharing knowledge and creating innovation in a globalized society. As the importance of civil society has been acknowledged in knowledge-sharing (Hasche et al., Citation2020; Kimatu, Citation2016; Vallance et al., Citation2020), the Quadruple Helix (QH) model extends the TH model by adding civil society as the fourth helix and explains the resource exchange and knowledge-sharing to achieve sustainability (Yun & Liu, Citation2019).

However, there is a lack of empirical studies with which to examine the roles of QH stakeholders in the process of knowledge exchange activities (Marques et al., Citation2021). Prior studies have examined that there is a likelihood that the imbalance regarding the stakeholders involved in the innovation system could occur (Kalenov & Shavina, Citation2018). Thus, there is a need for more case-based research at micro-levels that employ the QH model to better understand the complexity of collaborative activities. In addition, most of the previous studies on the QH model have focused on macro-perspectives, while sustainability-related activities often take place at the micro-level (Hasche et al., Citation2020; McAdam & Debackere, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2018). For example, Hasche et al. (Citation2020) highlighted the urgent need to examine the QH model from a micro-perspective by examining its dynamic relationships, synergies, collaborations, coordinated environments and value creation activities.

The present study responds to Hasche et al.’s (Citation2020) and Miller et al.’s (Citation2018) call for more QH research by examining a case study of a regional sustainability-related multi-stakeholders collaborative project (the SDGs project) through the lens of the QH model. The SDGs project took place between March and December 2020 in Ena City in the Tokai subregion of Chubu, Japan. The case study provides an opportunity to explore and understand the process of knowledge-sharing among stakeholders. By employing the QH model as the theoretical framework, this study explains the roles of government, industry, civil society and academia in knowledge-sharing processes in a collaborative project so that the findings from this study can be applied in other similar and future projects. A better understanding of the different roles of stakeholders enables us to explore and understand the process of knowledge-sharing among stakeholders from the perspective of the QH framework. The insights gained from the better understanding of the knowledge-sharing process and stakeholders’ roles could be employed by future collaborators of sustainability projects to become more effective. Thus, this study aims to answer the following two research questions. How did knowledge-sharing processes work in a regional sustainability project? How will the QH framework explain this phenomenon (i.e., the success of the regional sustainability project) so that the findings from this case study can be applied in future regional sustainability projects?

For research methods, we employed interviews with the stakeholders in addition to document analysis (e.g., communication records, transcripts of interaction and minutes of meetings with stakeholders during the planning, intervention and reflection stages of the project as well as reflective journals). Qualitative content analysis was applied to categorize data to induce patterns of communication and relationships among the helices.

According to the literature, the above-mentioned stakeholders play the following roles in the knowledge-sharing process. Industry adopts innovation platforms for knowledge creation, sharing and commercialization through joint research with academics (Yun & Liu, Citation2019). The industry provides access to resources and involves the participation of local stakeholders (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020). Academics play the leading role in capitalizing the knowledge creation and dissemination process and employ it as a leverage to interact with industry and government (Colapinto & Porlezza, Citation2012). The government supervises the industry supervisor by synergizing innovation or distributing the outcomes of the knowledge-sharing process at the local level (Marques et al., Citation2021; Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). Civil society help meet the needs of citizens as end users that incorporate the continuous process of feedback and iteration; the involvement of civil society supports the creation of social innovations, legitimization and justification for innovations; exerts a strong influence over the generation of knowledge and technologies through its demand function (Carayannis & Grigoroudis, Citation2016).

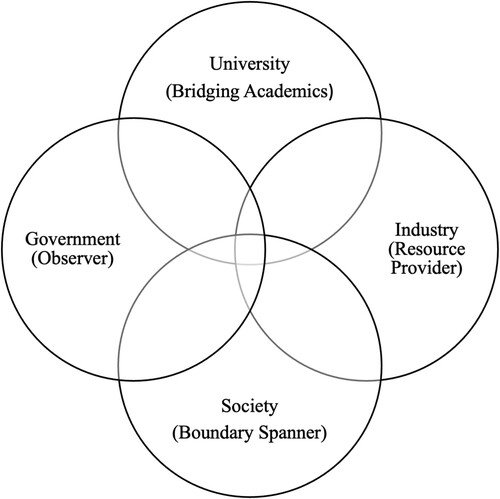

The findings confirmed the roles of stakeholders and their areas of influence, action and contribution in the context of a regional sustainability-oriented project as a knowledge-sharing network. The study discussed the roles of stakeholders that emerged from the SDGs project, such as ‘resource provider industry’, ‘boundary spanner civil society’, ‘observant government’ and ‘bridging academics’, which emulate a balanced QH model as a flexible overlapping system, in which individual institutional spheres and organizations can cross strong boundaries and each may undertake the role of the other (Etzkowitz, Citation2002). Such a balanced configuration could offer important insights for innovation and overcome the biases regarding the role of stakeholders to address regional issues related to sustainability (Ranga & Etzkowitz, Citation2013).

The current study contributes to the existing literature three-fold. First, few studies have employed the QH model in the context of sustainability. Second, most of the previous studies on the QH model have focused on macro-perspectives (Hasche et al., Citation2020; McAdam & Debackere, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2018), while sustainability-related activities often take place at the micro-level. Third, while fulfilling these research gaps, the study helps clarify the roles of the stakeholders, which extends the understanding of QH under an evolutionary process that is relevant for sustainability in a real setting.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 examines the literature on knowledge-sharing, sustainability, TH and QH. Section 3 describes the research design employed and the SDGs project. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the theoretical and practical implications of the findings from the SDGs project. Section 6 concludes with suggestions and recommendations for the future implementation of the collaborative model discussed herein.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Sustainability is defined as the process to satisfy the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to satisfy theirs (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020). Efficient production and application of knowledge remain one of the most important sources of regional competitiveness and sustainability (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020). A society aiming to promote sustainability has to maintain a balance between economic development, social well-being and environmental conservation (Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). Developed countries and regions have transitioned from economies driven by commodities and manufacturing to those driven by knowledge and innovation (Ruhanen & Cooper, Citation2004). Knowledge is a critical organizational resource that provides a sustainable competitive advantage in a dynamic economy and is generally analysed at the contextual level (Davenport & Prusak, Citation1998; Leydesdorff, Citation2012).

The knowledge-sharing activity refers to the provision of task information and know-how to help and collaborate with others to solve problems, develop new ideas, or implement policies or procedures (Cummings, Citation2004). Knowledge-sharing occurs not just within organizations but also among individuals across different organizations (Brown & Duguid, Citation1991). Knowledge-sharing may also be embedded in broader organizational networks, such as communities of practice, which are work-related groups of individuals who share common interests or problems and learn from each other through ongoing interactions (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). Prior literature examines the knowledge-sharing and innovation process by explaining the interactions among key stakeholders for knowledge transfer, innovation, job creation and sustainability (Asheim & Isaksen, Citation2002).

Productive knowledge exchange between stakeholders from different fields paves the way to the goal of achieving a sustainable society (Sampaolo et al., Citation2021). Knowledge-sharing plays an important role in enhancing sustainability through developing the innovation system in regional contexts with each helix playing a key role in the process (Gouvea et al., Citation2013; Hasche et al., Citation2020; Roman et al., Citation2020; Yun & Liu, Citation2019). The development of a democratic system requires interaction among various components in the society, where mutual learning and knowledge exchange takes place (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2010). This is consistent with the rationale of achieving SDGs which necessitates multi-stakeholders’ collaboration. The United Nations influences institutions such as universities, governments, non-government organizations and individuals to collaborate in order to achieve the SDGs (Amry et al., Citation2021; Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). Although the scope of sustainability is relevant globally, it is important to examine the effectiveness of collaborative activities that promote sustainability at the regional and grassroots level.

The TH model represents the collaborative relationship among stakeholders including academia, industry and government aimed to foster innovation. It has been used to help create, share and transfer knowledge for innovation among governments, industries and universities (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009; Etzkowitz, Citation1983: Hasche et al., Citation2020; Yun & Liu, Citation2019). The model assumes that academia plays the leading role in the innovation process because academics are able to capitalize on the knowledge creation and dissemination process and employ it as a leverage to interact with industry and government (Colapinto & Porlezza, Citation2012). Industry adopts innovation platforms for knowledge creation, sharing and commercialization through joint research with academics (Yun & Liu, Citation2019). A government could represent a statist role by employing the political authority given by the state to lead and have full control over its stakeholders in decision-making (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000). Studies such as Kimatu (Citation2016) suggested that the TH model is insufficient in explaining the innovation generation process that incorporates long-term sustainable growth due to a lack of focus on the local community.

Several researchers thus proposed to expand the TH model into the QH model by including the fourth helix to better explain the innovation process as a foundation of a knowledge-based economy. A number of candidates for the fourth helix have been proposed, such as financing information, media, culture and civil society (Colapinto & Porlezza, Citation2012; Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). The QH concept has been adopted by the European Commission for the preparation and implementation of the research and innovation smart specialization strategy (Marques et al., Citation2021). The model has been employed as a useful social context to disseminate responsible research and innovation practices (European Commission, Citation2016; Hasche et al., Citation2020).

The inclusion of civil society as a fourth helix represents the needs of citizens as end users that incorporate the continuous process of feedback and iteration (Hoglund & Linton, Citation2018; Leydesdorff, Citation2012). The structure of civil society in the context of QH is not strictly defined and it could vary in terms of its institutional forms, formality, autonomy and power. The inclusion of end users and civil society has been highlighted as a critical component in the development of regional projects (Hasche et al., Citation2020; Kriz et al., Citation2018). Thus, we adopt the QH model that incorporates civil society as its fourth helix to capture the relationships and roles of academics, government, industry partners and civil society in the knowledge-sharing and regional innovation processes (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009).

The prior literature has highlighted several advantages of the QH model over the TH model in the creation of sustainable innovation. First, the QH model can complement and enhance the TH model by providing ‘bottom-up’ insights from civil society to complement ‘top-down’ views from academia, industry and government in regional development (Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, Citation2014). Second, the involvement of civil society supports the creation of social innovations, legitimization and justification for innovations (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009; Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, Citation2014). Civil society is considered to be the end user of innovation and exerts a strong influence over the generation of knowledge and technologies through its demand function (Carayannis & Grigoroudis, Citation2016). Third, the engagement of civil society in designing regional development strategies and determining strategic priorities is essential for their commitment to and ownership of a development agenda (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009). QH brings civil society into the analysis of the dynamics of the existing TH model (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2009; Etzkowitz, Citation2003) in regional innovation and sustainability. Regional innovation networks play an important role in motivating and improving the attitudes of stakeholders to generate innovation in products and services (Schoonmaker & Carayannis, Citation2013). Collaboration that is aimed to tackle sustainability or ecology issues represents a platform and opportunity for interdisciplinary and inter-stakeholder problem-solving (Carayannis & Campbell, Citation2010). Interaction among these stakeholders, especially at the regional and local levels, initiated by individuals and/or organizations that have convening power and command respect across the TH, has been found to be the key to realizing the potential of a knowledge base.

Collaboration between stakeholders across boundaries can be certainly challenging. Prior literature has argued that each stakeholder insisted on the relevance of their distinct norms, practices and routines that solidify internal group cohesion but might not be helpful for external group collaboration (Battilana & Dorado, Citation2010). However, past literature has not explored the specific roles that stakeholders could play in promoting sustainability in the QH model, especially in civil society. In addition, most studies have taken a macro-perspective and therefore did not account for understanding the complexity of these interactions among the helices at the micro-level (McAdam & Debackere, Citation2018). In this context, the current study aims to analyse the interaction process among stakeholders and explain the roles of each stakeholder in achieving knowledge-sharing in the context of undertaking an SDGs project.

3. RESEARCH DESIGN

We employ a case study approach for the current research. Previous research suggests that a more detailed examination is needed of the dynamic relationship between the different actors in a QH model. Case-based research at micro-levels is needed to further understand the complexity of activities that take place in a QH setting to develop current theoretical knowledge (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Hasche et al., Citation2020). A case study approach is appropriate for this study as it attempts to provide a comprehensive analysis of various processes, with the examination of stakeholders’ roles, perspectives, or experiences during and as a result of the interactions in the knowledge-sharing process. This approach leads to unusual, innovative, and ground-breaking theoretical insights that could be applied beyond a specific case (Piekkari et al., Citation2009; Siggelkow, Citation2007; Yin, Citation2017).

The SDGs project has been selected as a single case study as it was developed with extensive efforts, participated by multiple stakeholders, achieved evident sustainable outcomes and was accessible for data collection with the key representatives of every organization. In the following sections we explain the SDGs project to further provide the context of the study, the research method and data analysis.

3.1. The SDGs project

The SDGs project was initiated by two faculty members affiliated with the Graduate School of Management at Nagoya University of Commerce and Business (NUCB). The project aimed to promote knowledge-sharing and social innovation regarding SDGs of a local corporate-sponsored forest conservation programme known as the Ricoh Ena Forest (REF) programme in collaboration with global and regional stakeholders. The planning and execution of the project lasted approximately nine months, as specified in Table A1 of Appendix A in the online supplemental data. The Ricoh Ena Forest is located in Ena City, which is adjacent to Ricoh Elemex Corporation, a manufacturing subsidiary of the Ricoh Group, a multinational corporation headquartered in Japan. Ena City is a small town with an estimated population of approximately 49,000 people in Gifu prefecture (). The forest spans over 40 ha of land and remains undeveloped (). The Ricoh Elemex employees interested in managing forests as volunteers initiated a forest programme in 2010 to mark the 10th meeting of the conference of the parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP 10) held in Nagoya, Japan.

Figure 1. Location of Ena City, Gifu prefecture, Japan.

Source: Figure reproduced with permission of the NPO Ena-shi Sakaori Tanada Preservation Association (https://sakaori-tanada.com/english/introduction/outline/).

Figure 2. Ricoh Ena Forest (REF) programme forest area in Ena City.

Source: Figure reproduced with permission from Ricoh Company Ltd (https://www.ricoh.com/sustainability/environment/biodiversity/contribution/ena_forest).

In 2014, a forest management committee (REF management committee) was established to encourage the participation of local community members. The committee organized forest-preservation activities aimed at increasing environmental awareness among the young generation and the social and physical well-being of local residents. The forest is open for educational visits, from elementary school to college level, to understand the forest ecosystem and learn about the biodiversity in the region. The stakeholders involved in the project were classified into four categories according to the QH model: academia, industry, government and civil society.

Two faculty members of NUCB played the role of the SDGs project’s initiators, organizers, and facilitators for all stakeholders. A total of 17 MBA students from NUCB joined the SDGs project to learn about the sustainable initiative of the Ricoh Group and its viability for the organization and other stakeholders. In addition, one international researcher from Keio University, Japan, was invited to join the SDGs project to provide research expertise in the relevant domain.

The REF programme is under the umbrella of sustainability initiatives by the Ricoh Group Headquarters (HQ) Sustainability Division. The industry partners of the SDGs project were the Ricoh Group HQ located in Tokyo and their manufacturing subsidiary, Ricoh Elemex, located in Ena City. Two senior managers from the Ricoh Group HQ Sustainability Division participated as representatives of HQ. They provided key information about the group’s mission, corporate strategy and nationwide practices employed in sustainability projects within different parts of Japan.

The Ena City government is responsible for facilitating residents in preserving the environment and maintaining the relevant facilities, but was not directly involved in the REF programme. Three government officials responsible for planning, environment and forestry participated in the SDGs project. They were responsible for initiating and supporting relevant activities in the city.

Civil society was represented by Ena residents, members of the REF management committee and a non-profit organization (NPO) based in the city. The REF committee members, who were also local residents, shared their motivation for planning and organizing activities for the general public. The local NPO, the Ena City International Exchange Association (EIEA), was represented by its executive director. The EIEA provided insights from the residents’ frame of reference.

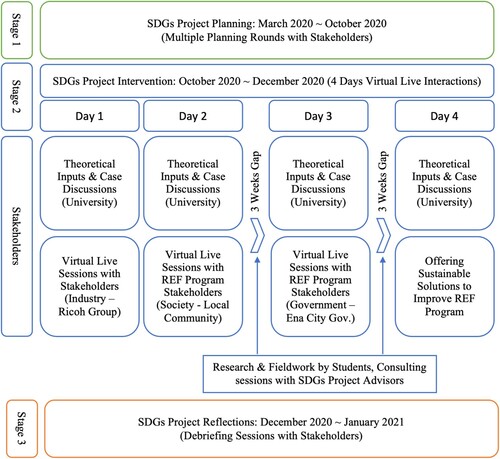

The SDGs project’s academic participants were tasked with evaluating the sustainability of the REF programme and making recommendations to improve the outcomes while considering the needs of the other stakeholders. The project was conducted in a virtual environment, enabling all participants and stakeholders to interact with each other instantaneously. The SDGs project proceeded sequentially in three stages ().

3.2. Methods

At all stages of the SDGs project, we collected data through interviews with stakeholders and document analysis (e.g., communication records, transcripts of interaction, minutes of meetings with stakeholders and reflective journals during the planning, intervention and reflection stages of the project; see Table A1 of Appendix A in the online supplemental data). In addition, questionnaires and reports submitted by student participants during the SDGs project were used.

At the planning stage, we held meetings with different stakeholders, and minutes of meetings were taken to understand the background and needs in sustainability amongst stakeholders. Data were collected from Ricoh HQ staff and Ricoh Elemex representatives to understand the background and evolution of the forest. Their future plan for the forest and the differences in roles and contribution among headquarter and regional offices with respect to sustainability were discussed in respective meetings. The Executive Director of the EIEA provided additional information on the roles and level of participation by the local community members in the forest project and support from the local government in achieving sustainability-relevant outcomes in the city.

The other data were collected through means of reflective journals written by participants throughout the implementation phase. A total of 17 NUCB students participated in lectures and had discussions with respective project stakeholders through workshops conducted with the goal of creating sustainable proposals for the REF programme. Through four workshop sessions and discussions, each about 6 hours per session, from October to December 2020, every participant had to write their own reflective journal to describe their learnings and reflections at the end of each session. The reflective journal method is important to provide evidence of learnings from participants’ perspectives. The approach contributes toward the understanding of how external participants learned and changed perceptions about sustainability after engaging with other parties.

During the reflection stage, we conducted semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders of the SDGs project. The interviewees were the immediate project stakeholders. Each of the interview sessions lasted between 60 and 90 min and the interview contents were recorded into interview notes with the interviewees’ permission. Interview questions covered: the company’s mission and purpose, roles in the forest project, information flow between departments/institutions, interaction with stakeholders, contribution to forest activities, and individual takeaways through stakeholders’ engagement. The advantage of triangular data sources from stakeholders would reduce one-sided biases and increase the trustworthiness of data as highlighted in QH studies. Table A2 in Appendix A in the online supplemental data summarizes the demographic details of the interviewees.

3.3. Data analysis

We used the qualitative content analysis approach to analyse the collected data. The qualitative content analysis builds on an inductive coding scheme through the analysis of collected data (Drisko & Maschi, Citation2016; Gaur & Kumar, Citation2018) and subsequent summarization and analysis of the coded text. As Hasche et al. (Citation2020) noted, a common way to code is to work with different categories. Based on the theoretical framework of the QH as a network of relationships with a focus on actors, resources, and activities, we started to categorize the empirical data in line with the four helices of government, industry, academia, and civil society. We employed content analysis, not thematic analysis, ‘preset’ the four categories relevant to stakeholders (i.e., academia, industry, government and civil society) drawn from the existing literature and the researchers’ involvement in the SDGs project, and categorized the collected data into these four categories, which resulted in creating subcategories.

In the context of the SDGs project, the process of coding and categorization was documented as follows. First, texts extracted from the data were divided into smaller parts called ‘meaning units’. These are the parts of the text with some meaning; in the case of the SDGs project, the text was divided into smaller meaning units such as ‘I learned about environmental conservation and community engagement’ and ‘We would continue this collaboration to find solutions for the sustainability strategy.’ These meaning units were labelled by formulating the codes. The assigned codes were short, having one to two words describing each meaning unit, for example, ‘community engagement’, ‘collaboration’, ‘shared value’, etc. Potential subcategories were identified by grouping codes that were similar in their content or context (e.g., potential subcategories were ‘enhanced exposure and interaction with all stakeholders’, ‘emergence of diverse perspectives on sustainability’ and ‘realization of gaps between theoretical knowledge and practical applications’, among others). The potential subcategories were sorted by examining all textual data and were divided into four preset respective helices to reflect a more all-inclusive understanding. As shown in Table A2 of Appendix A in the online supplemental data, the researchers considered the diversity of their country of origin and professional experience. Each participant was assigned a specific code that described their affiliation in accordance with the QH model.

4. RESULTS

Results of the analysis are classified into subcategories under each helix as per the following descriptions.

4.1. Academia

4.1.1. Realization of the gaps between theoretical knowledge and practical applications

The interactions among stakeholders augmented their understanding of the project scope and enhanced a shared understanding among clusters of stakeholders. The recognition of the difference in familiarity with the notion of sustainability in general, and its application in particular, was evident. Academic participants were typically conscious of the theoretical concepts. The project design enabled them to modernize their theoretical side before venturing into the field to witness the practicality of such concepts. One participant mentioned: ‘There were many times I found myself saying “That is what they meant in class … .” It was a very hands-on, practice-based project. It tested many of the design philosophies I have studied. The practical experience was priceless’ (IS-1).

The comment by an international student revealed the contrast in their understanding of sustainability-relevant concepts in academic settings. Another participant documented this in their reflective journal:

Before the course, I had a ‘BIG WHY’ about companies who adopt SDGs in their businesses and business models. Thanks to the project, I have gained understanding and received comments for my proposal created for the Ricoh Ena Forest. If there is an opportunity, I would like to implement our plan into reality through the support of the regional stakeholders. (IS-10)

The statement illustrates the emergence of conceptual clarity after interactions with stakeholders. The phenomenon highlights the broader implications of exposure. Such as the possibility of incorporating proposed enhancements within current initiatives was discussed among the stakeholders.

4.1.2. Emergence of diverse perspectives on sustainability

The project structure enabled participants to initiate a communication loop connecting every major stakeholder. The process involved knowledge-sharing through information sessions, interviews, proposal discussions, and feedback sessions among stakeholders.

The interaction allowed academic participants to gain insights into the REF programme and discuss the motivational factors behind the endeavour. The participants initiated the conversation with a fundamental perception of the project as a ‘Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)’ initiative. As discussions evolved, they realized that the REF programme was much bigger than a simple CSR project. One participant stated:

From the direct interview with stakeholders (Ricoh HQ and Ricoh Elemex) at the breakout session, I got a clearer impression that environmental conservation and community engagement was the top priority. Project representatives were not too worried about financial sustainability. (IS-3)

4.1.3. Convergence and extension of theoretical knowledge

The interactions and exchange of information empowered the convergence of knowledge among all stakeholders. The confluence of information resulted in finding the rationale for existing theories and eventually extending such frameworks in line with stakeholders’ experiences and ground realities. For instance, business students are familiar with the classic concept of shared value advocated by Porter and Kramer (Citation2011). After the SDGs project one participant stated: ‘I learned a lot about sustainable development projects in companies and the overall externalities and internal issues that made those projects hard to develop. I also learned how both can create value for the companies and the society’ (IS-17).

The insights gained from diverse perspectives and learnings can be generalized toward the creation of shared values. In fact, academic participants are extending the classic concept of shared value with a core focus on corporate profitability by incorporating the sustainability-relevant needs of society.

4.2. Industry

4.2.1. Understanding different perspectives and approaches toward sustainability

The SDGs project collaboration extended the base of shared knowledge and motivation among corporate participants. The senior managers from Ricoh Group HQ appreciated the diversity of opinions and acknowledged the practicality of interactions in feedback sessions with academics. The absence of a coordinated approach by Ricoh Group HQ was highlighted by students in their consultancy reports. The HQ representative shared their opinions after the project in the following words:

We would continue this collaboration to find solutions for the sustainability strategy of our corporation. I would like to compare case studies between Japan and foreign countries through the international students. We would follow-up to invite the academics for a joint research presentation to share about collaboration of SDGs projects with other institutions at the national level. (RICOH-1)

4.2.2. Out-of-the-box thinking for local challenges

Employees of Ricoh Elemex, the local manufacturing subsidiary of the Ricoh Group, were able to consider innovative ways to organize forest activities while considering user benefits. The consultancy reports by student groups highlighted the need to create awareness among the local population regarding regular activities in the forest. The reports highlighted the need to select suitable media to disseminate information at regular intervals. The students and Ricoh Elemex employees deliberated on effective ways of communicating with prospective and regular participants for forest conservation activities. An employee from Ricoh Elemex expressed his views as follows:

I could see how our daily activities in the forest could be further promoted via social media to reach out to more participants. This enables us to achieve a common goal as we have shared values about the creation of a sustainable environment for all. (ELEM-1)

The interaction with academic participants helped corporate members in finding innovative solutions for the local issues. They learned about the critical areas for such projects and discussed proposed improvements by students while engaging other stakeholders.

4.2.3. Creating a corporate policy to manage sustainable projects for enhanced impact

Discussion among Ricoh Group HQ managers and their subsidiary employees revealed differences in their understanding of the REF programme. The HQ oversees multiple forests in Japan and considers forest projects a vital component of its corporate SDGs portfolio. The problem arises when employees at local subsidiaries are not familiar with SDGs compliance mandates and their relevance with corporate strategies. Local subsidiaries try to manage the location according to their understanding of the project scope and implications. The consultancy reports highlighted the importance of eliminating such discrepancies and creating a uniform policy to manage such facilities.

4.3. Government

4.3.1. Inclusion of SDGs in local government policy

The project provided government representatives with a window to explore and understand the application of SDGs at the policy and governance levels. Although the local government had managed the local facilities and protected the environment, they were not familiar with implementing SDGs in a larger context with consideration of stakeholders’ needs. Discussions with the academic community allowed them to understand the theoretical ideas and concepts behind the widespread movement of sustainable initiatives. In the annual report 2019 by the Ena government, there was no indication of SDGs and sustainability-oriented projects. Following the end of the SDGs project, the annual report for 2020 contains multiple SDGs references and relevant sustainability-oriented policy measures and actions.

4.3.2. Creating awareness among city officials and local residents

The Ena City government officials expressed their gratitude toward international students and researchers for their interest in forest conservation activities in the vicinity. In the SDGs project feedback session, the officials discussed the following two actions: organizing an introductory seminar with other government officials and placing relevant SDGs logos at the community centre to create awareness among the general public. The government representative expressed their views as follows:

We considered the importance of shared value to be the key toward enabling the city to achieve as a future SDGs city. This collaboration provides precedence for other engagements beyond members in Ena City. Thanks to the faculty member for bringing us through the learning process. (ENA-2)

The government representative realized the importance of SDGs. They reflected on creating a sustainability paradigm to engage local companies, subsidiaries and residents.

4.3.3. Sustainability initiatives by corporations and the role of local government

The Ricoh Elemex staff and REF management committee had been managing forests and inviting local residents for forest conservation activities for a long time, but the local government was not familiar with the REF programme. The government officials interacted with corporate representatives while providing assistance if required. The following statement captures the views of a government representative:

Even though our city government had known about the Ricoh Elemex and Ricoh Ena Forest located in our city, we had never communicated or collaborated about sustainability issues until this project. We have learnt a lot about each other. (ENA-1)

The SDGs project established a link between local governments and corporations to share knowledge with each other. Through the interaction, the government officials were able to familiarize themselves with sustainable projects by corporations in their vicinity.

4.4. Civil society

4.4.1. Maintaining the forest is important for the local environment

The civil society stakeholders in the SDGs project were familiar with the forest conservation activities organized under the REF programme and its benefits for the community. The academics paid a forest visit organized by the EIEA executive director. The involvement and presence of international students in the local forest conservation programme helped the local residents to acknowledge the importance of the REF programme for the local community and the global audience. Local participants expected the consultancy report to offer innovative solutions to invigorate the local population’s interest in forest conservation activities.

4.4.2. Issues related to participation of local residents

One of the issues faced by the REF management committee was the lack of sufficient volunteers and the small number of participants for certain activities. The activities were regularly organized by the REF management committee, but repetition of activities was not sufficient to attract a large audience and volunteers. Through consultancy reports, the students suggested that the REF management committee should use different means of communication, such as different social media sites and applications to attract the target audience. An employee of Ricoh Elemex, who is also part of the forest management committee, stated the following after viewing the proposal by students: ‘Through the proposals, I realized the lack of communication with local residents to reorganize the forest activities even though we are ‘neighbours’ in Ena City’ (ELEM-1).

The proposed solutions included targeted social media posts to attract like-minded people to such events. Students also recommended and created a prototype website for REF programme activities.

4.4.3. Considering fresh activities beyond forest conservation

Before the SDGs project, the REF management committee focused primarily on forest conservation-related activities. The interaction with the SDGs project participants allowed them to assess other areas for expansion. For instance, consultancy reports concentrated on the establishment of forest schools, which allow school children to visit the forest regularly and learn about the environment, forest conservation, and sustainability. The REF management committee was satisfied with the contemporary solution recommended by SDGs project participants. Some community members recollected their thoughts as follows:

I was surprised with the strong interest toward the REF program by the international students and amazed by the synergy created at the end of the online interview sessions. Thus, we came together to guide the students for the initiated fieldwork and followed up interviews outside the project. (ELEM-1 and EIEA-1)

5. DISCUSSION

Stakeholders of a regional innovation system have traditionally been observed not to interact with each other and instead operate independently. Consequently, when various stakeholders are involved in a joint activity, the individual stakeholder shows the expansion of their role beyond the definition prescribed by the QH model (Kalenov & Shavina, Citation2018). Interaction among different groups in the innovation development process generates uneven collaboration behaviours, where hesitation to cooperate and change of behaviour are observed in times of crisis (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020).

In this study, we observed a significant knowledge gap between theoretical understanding and practical application of sustainability practices. Initially, each stakeholder had a different understanding and perception of the scope and objectives of the project. The knowledge gap refers to the application of knowledge that gets ‘lost before/in translation’ (Shapiro et al., Citation2007; Van de Ven & Johnson, Citation2006).

In the innovation development process, academia provides a space and service to generate knowledge and apply it to practice (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020). Our study showed that academics facilitated active interaction among the stakeholders and connected global and regional knowledge communities through their networking and collaboration activities. Academics were able to bridge the knowledge gap across stakeholders on sustainability topics. This role corresponds to what Trippl (Citation2013) calls ‘bridging academics’. Academics acted as knowledge diffuser agents by ensuring knowledge mobility and establishing an outcome-based partnership (Benneworth & Fitjar, Citation2019). However, the process of transferring tacit knowledge from academics to other stakeholders is not sufficient to contribute to the innovation development process unless the innovation has been applied and contributes to the industry’s competitive advantage (Amry et al., Citation2021). We observed in our case that academia realized the need to understand the practical application and process of sustainable entrepreneurship while the industry realized the importance of reaching out to local stakeholders to widen the channels of their innovation-generating process.

The industry is expected to be engaged in the knowledge-sharing process with other stakeholders when it aims to improve the efficiency of the research and development process that drives innovation (Galvao et al., Citation2019). Our observation of Ricoh Corporation suggests that it helped drive sustainable solutions for other stakeholders by providing strategic resources and access to the forest for them to achieve common goals, consistent with the resource-based view as a ‘resource provider’ (Barney, Citation2001). Our study provides evidence that an industry that provides access to resources and prioritizes the involvement of local stakeholders will better achieve its sustainability goals (Luengo-Valderrey et al., Citation2020).

The government assumes the roles of the public voice and the industry supervisor by synergizing innovation, knowledge, and technology (Marques et al., Citation2021). In the SDGs project, representatives from the Ena government effectively shared the city policy, while providing the opportunity for knowledge creation to evolve with new sustainability practices following the conclusion of the project. The local government-initiated seminars and sessions for local government officials to disseminate sustainability knowledge at the local level (Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). In our study, the government is characterized as playing an observing role, instead of a statist one. Under a typical statist role, a government would undertake leadership with the political authority given by the state to lead and have full control over its stakeholders in decision-making (Etzkowitz & Leydesdorff, Citation2000). The case provides evidence that governments are able to assume roles outside of their traditional regulatory ones in the context of sustainable development (Galvao et al., Citation2019).

The role of civil society in innovation has not yet been well explained and conceptualized, particularly in the context of sustainability-driven projects (Roman et al., Citation2020). Civil society represents the end-users of innovation projects, where they are expected to identify sustainable development issues that have high risks and avoid potentially dangerous decisions/projects (Zhou & Etzkowitz, Citation2021). In the current study, EIEA represents the civil society helix. With years of experience operating in Ena City, EIEA has built trust, fostered relations, and reconciled the interests of diverse local stakeholders. This role is referred to as a boundary spanner that fosters the exchange of knowledge that crosses institutional boundaries (Briley et al., Citation2015).

In this study, we found that every stakeholder has engaged and participated during the sessions facilitated by the project. This study clarifies the roles of stakeholders from the respective helices as ‘bridging academics’, ‘resource providing-industry’, ‘observant government’ and ‘boundary-spanning civil society’. When these roles interact in a knowledge-sharing network, it emulates a balanced helix model as a flexible overlapping system, in which separate institutional spheres and organizations can cross strong boundaries and each may undertake the role of the other (Cai & Etzkowitz, Citation2020; Etzkowitz, Citation2002). In a balanced helix model, no single party exerts stronger control over other stakeholders. We observed that each QH stakeholder assumes a major role in the sustainability-based collaboration project (). International and local stakeholders have gained motivation and interest in the exchange of ideas and discussions. Through such interactive sessions, stakeholders have reduced their cognitive distance and overcome knowledge complementarities (Cowan et al., Citation2007). The outcomes from the collaborations among the stakeholders have contributed to knowledge creation and knowledge-sharing to generate innovative solutions to advance sustainability. Such a ‘balanced’ configuration could offer important insights for innovation (Ranga & Etzkowitz, Citation2013) and overcome the biases on the role of stakeholders to address regional issues related to sustainability.

While most of the prior QH studies employed a macro-perspective (Hasche et al., Citation2020; McAdam & Debackere, Citation2018; Miller et al., Citation2018), our study provides empirical evidence that supports the balanced QH model and clarifies the roles of each stakeholder from the micro-perspective.

Our findings also highlighted the importance of establishing dense networks at the regional level that share an interest in achieving sustainability goals. The collaboration among stakeholders working in their domains for sustainability can be helpful in achieving the SDGs in the long run, by disseminating the knowledge and filling the gaps among stakeholders. To facilitate this, we should aim at adopting a balanced helix model in promoting a regional sustainability project because stakeholders’ collaboration in line with the balanced helix model can be more equal for partners to actively collaborate and share their knowledge and expertise toward innovation, by stakeholders playing the following roles: academia as bridging academics; industry as resource provider; government as an observer; and civil society as boundary spanner.

The implication is to recommend a sustainability policy that encourages more bottom-up initiatives to address gaps with a user-centric approach, in line with the balanced helix model, and derives the proof of concept that is with consensus by both the internal and external actors. The construct of the iterative process with such a dense network will ensure mutual ownership and accountability. The results will influence policymakers to open their doors and consider multiple collaborative projects to achieve long-term sustainability in their regional settings.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This study employs the QH framework to explain the knowledge-sharing processes and its outcomes amongst stakeholders in the context of a regional sustainability project. The study contributed to sustainability, QH and knowledge-sharing literature. At the initial stage of interactions among the stakeholders, we observed a gap between theoretical understanding and practical application of sustainability practices. The project facilitated inter-exchanges of knowledge among stakeholders in the respective helices, which addressed this gap. We explained the roles of stakeholders and the process of the interactions which have not only enhanced the understanding among the partners but also improved the effectiveness of a regional sustainability-based collaborative project. Academics were able to bridge the knowledge gap and serve as the knowledge diffuser agents, also called the ‘bridging academic’. Industrial partners represented a resource provider and involved other stakeholders, especially community members, to overcome inertia to develop sustainable solutions for the local communities while fulfilling the regulatory requirements regarding sustainability-relevant initiatives. Collaborative arrangements could influence passive stakeholders, such as local governments, to be more actively engaged with other stakeholders. Local governments acted as an observer and could use this opportunity to observe and interact with stakeholders through a grounded approach and use the experience in formulating new sustainability policies. Members of society played an important role to build trust, fostering relations, and reconciling interests of diverse local stakeholders as boundary spanners within the regional network. This study examines the roles of local stakeholders from a micro-perspective in regional settings. The findings provide practical implications to overcome the boundary among stakeholders by identifying a theoretical model — a balanced QH model — that frames their respective roles.

The findings must be viewed in light of the limitations of this study. First, the research uses a single case study – the SDGs project – which narrows the possibility of generalization. Further research could adopt case comparisons to study two or more cases based on regional projects to improve the validity of the employed model. Second, there was an over-reliance on community clusters, which might have resulted in a bias in the relevant knowledge shared with other helices. Future studies may apply a longitudinal approach to investigate the trajectory of knowledge transformation through different stages of communication. Such an investigation will provide a balanced, in-depth knowledge of the different layers of the QH model used in this study.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.1 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are really grateful to the Ricoh Corporation, Ricoh Elemex, Ena Forst Management Committee, Ena City International Exchange Association (EIEA) and Ena City government for their support and assistance for the SDGs project.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

REFERENCES

- Amry, D. K., Ahmad, A. J., & Lu, D. (2021). The new inclusive role of university technology transfer: Setting an agenda for further research. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 5(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2021.02.001

- Asheim, B. T., & Isaksen, A. (2002). Regional innovation systems: The integration of local ‘sticky’ and global ‘ubiquitous’ knowledge. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 27(1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013100704794

- Barney, J. B. (2001). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 27(6), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700602

- Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.57318391

- Benneworth, P., & Fitjar, R. D. (2019). Contextualizing the role of universities to regional development: Introduction to the special issue. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 6(1), 331–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2019.1601593s

- Briley, L., Brown, D., & Kalafatis, S. E. (2015). Overcoming barriers during the co-production of climate information for decision-making. Climate Risk Management, 9, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2015.04.004

- Brown, J. S., & Duguid, P. (1991). Organizational learning and communities-of-practice: Toward a unified view of working, learning, and innovation. Organization Science, 2(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2.1.40

- Cai, Y., & Etzkowitz, H. (2020). Theorizing the Triple Helix model: Past, present, and future, Triple Helix, 7, 189–226. https://doi.org/10.1163/21971927-bja10003

- Carayannis, E., & Grigoroudis, E. (2016). Quadruple innovation helix and smart specialization: Knowledge production and national competitiveness. Foresight and STI Governance, 10(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.17323/1995-459x.2016.1.31.42

- Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2009). ‘Mode 3’ and ‘QH’: toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. International Journal of Technology Management, 46(3/4), 201–234. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2009.023374

- Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. J. (2010). Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other?: A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development, 1(1), 41–69. https://doi.org/10.4018/jsesd.2010010105

- Carayannis, E. G., & Rakhmatullin, R. (2014). The quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialisation strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5(2), 212–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-014-0185-8

- Colapinto, C., & Porlezza, C. (2012). Innovation in creative industries: From the Quadruple Helix model to the systems theory. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 3(4), 343–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-011-0051-x

- Cowan, R., Jonard, N., & Zimmermann, J. B. (2007). Bilateral collaboration and the emergence of innovation networks. Management Science, 53(7), 1051–1067. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0618

- Cross, R., & Cummings, J. N. (2004). Tie and network correlates of individual performance in knowledge-intensive work. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 928–937. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159632

- Cummings, J. N. (2004). Work groups, structural diversity, and knowledge sharing in a global organization. Management Science, 50(3), 352–364. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1030.0134

- Davenport, T. H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working knowledge: How organizations manage what they know. Harvard Business School Press.

- Drisko, J. W., & Maschi, T. (2016). Content analysis. Oxford University Press.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Etzkowitz, H. (1983). Entrepreneurial scientists and entrepreneurial universities in American academic science. Minerva, 21(2/3), 198–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01097964

- Etzkowitz, H. (2002). The triple helix of university–industry–government: Implications for policy and evaluation. In: Working Paper 2002.11. Sweden: Science Policy Institute.

- Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Innovation in innovation: The triple helix of university industry–government relations. Social Science Information, 42(3), 293–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184030423002

- Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and ‘Mode 2’ to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4

- European Commission. (2016). The Horizon 202 Work Programme 2016–2017 Science with and for Society. European Commission Decision C (2016) 8265.

- Galvao, A., Mascarenhas, C., Marques, C., Ferreira, J., & Ratten, V. (2019). Triple helix and its evolution: A systematic literature review. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 10(3), 812–833. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSTPM-10-2018-0103

- Gaur, A., & Kumar, M. (2018). A systematic approach to conducting review studies: An assessment of content analysis in 25 years of IB research. Journal of World Business, 53(2), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.11.003

- Gouvea, R., Kassicieh, S., & Montoya, M. J. R. (2013). Using the quadruple helix to design strategies for the green economy. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 80(2), 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2012.05.003

- Hasche, N., Hoglund, L., & Linton, G. (2020). Quadruple helix as a network of relationships: Creating value within a Swedish regional innovation system. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(6), 523–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2019.1643134

- Hoglund, L., & Linton, G. (2018). Smart specialization in regional innovation systems: A QH perspective. R&D Management, 48(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12306

- Kalenov, O., & Shavina, E. (2018). The role of ‘Triple Helix’ innovative model in regional sustainable development. E3S Web of Conferences, 41, 04054. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/20184104054

- Kimatu, J. N. (2016). Evolution of strategic interactions from the triple to quad helix innovation models for sustainable development in the era of globalization. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 5(16), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-016-0044-x

- Kriz, A., Bankins, S., & Molloy, C. (2018). Readying a region: Temporally exploring the development of an Australian regional QH. R&D Management, 48(1), 25–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12294

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Leydesdorff, L. (2012). The triple helix, QH, … , and an N-tuple of helices: Explanatory models for analyzing the knowledge-based economy? Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 3(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-011-0049-4

- Luengo-Valderrey, M.-J., Pando-García, J., Periáñez-Cañadillas, I., & Cervera-Taulet, A. (2020). Analysis of the impact of the triple helix on sustainable innovation targets in Spanish technology companies. Sustainability, 12(8), 3274. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12083274

- Marques, C., Marques, A. V., Braga, V., & Ratten, V. (2021). Technological transfer and spillovers within the RIS3 entrepreneurial ecosystems: A quadruple helix approach. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 19(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2020.1777909

- McAdam, M., & Debackere, K. (2018). Beyond ‘triple helix’ toward ‘QH’ models in regional innovation systems: Implications for theory and practice. R&D Management, 48(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12309

- Miller, K., McAdam, R., & McAdam, M. (2018). A systematic literature review of university technology transfer from a quadruple helix perspective: Toward a research agenda: Review of university technology transfer. R&D Management, 48(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12228

- Piekkari, R., Welch, C., & Paavilainen, E. (2009). The case study as disciplinary convention: Evidence from international business journals. Organizational Research Methods, 12(3), 567–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428108319905

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2011). Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89(1–2), 62–77.

- Ranga, M., & Etzkowitz, H. (2013). Triple helix systems: An analytical framework for innovation policy and practice in the knowledge society. Industry and Higher Education, 27(4), 237–262. https://doi.org/10.5367/ihe.2013.0165

- Roman, M., Varga, H., Cvijanovic, V., & Reid, A. (2020). Quadruple helix models for sustainable regional innovation: Engaging and facilitating civil society participation. Economies, 8(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8020048

- Ruhanen, L., & Cooper, C. (2004). Applying a knowledge management framework to tourism research. Tourism Recreation Research, 29(1), 83–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2004.11081434

- Sampaolo, G., Lepore, D., & Spigarelli, F. (2021). Blue economy and the quadruple helix model: The case of Qingdao. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(11), 16803–16818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01378-0

- Schoonmaker, M. G., & Carayannis, E. G. (2013). Mode 3: A proposed classification scheme for the knowledge economy and society. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 4(4), 556–577. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-012-0097-4

- Shapiro, D. L., Kirkman, B. L., & Courtney, H. G. (2007). Perceived causes and solutions of the translation problem in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 50(2), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24634433

- Siggelkow, N. (2007). Persuasion with case studies. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160882

- Trippl, M. (2013). Scientific mobility and knowledge transfer at the interregional and intraregional level. Regional Studies, 47(10), 1653–1667. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.549119

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming Our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development.

- Vallance, P., Tewdwr-Jones, M., & Kempton, L. (2020). Building collaborative platforms for urban innovation: Newcastle city futures as a quadruple helix intermediary. European Urban and Regional Studies, 27(4), 325–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776420905630

- Van de Ven, A. H., & Johnson, P. E. (2006). Knowledge for theory and practice. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 802–821. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527385

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and method. Sage.

- Yun, J. J., & Liu, Z. (2019). Micro- and macro-dynamics of open innovation with a quadruple-helix model. Sustainability, 11(12), 3301. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123301

- Zhou, C., & Etzkowitz, H. (2021). Triple helix twins: A framework for achieving innovation and UN sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 13(12), 6535. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13126535