?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This paper investigates the impact of reshoring, defined as the relocation of previously offshored production activities back to the home country or to a neighbouring country, on the productivity of manufacturing firms. It uses data from the European Reshoring Monitor on European firms in the period 2014–18. Reshoring increased total factor productivity of small and medium-sized firms, but did not affect productivity of large firms. The positive effect was stronger for firms that had offshored production to some Asian countries.

1. INTRODUCTION

In previous decades, manufacturing firms in developed economies had extensively delocalised their production to other countries. More recently, however, shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic, geopolitical tensions, new conflicts and trade frictions between countries have affected the worldwide economy, leading to questions about the sustainability of the trend towards globalisation and the organisation of global value chains (Barbieri et al., Citation2020; Canello et al., Citation2022). Many firms are therefore reconsidering the geographical location of their production activities, and moving manufacturing back to their home country (backshoring) or nearby (nearshoring).

Previous studies have identified a range of factors that explain reshoring decisions (McIvor and Bals Citation2021). These factors can generally be grouped into two broad categories depending on whether they are external or internal to the firms. Among the external factors, some concern the location of the offshoring, such as reduced cost advantage of producing in emerging economies due to increased labour, energy and commodities costs, underestimation of and increases in offshoring costs such as logistics, freight, and supply chain coordination costs, reduced operational flexibility and supply chain disruptions (Stentoft et al., Citation2018). Others are related to the home country, such as increased labour productivity from automation and technology improvements, more flexibility of the labour market, synergies between manufacturing and research and development (R&D) activities and untapped production capacity (Ancarani et al., Citation2019; Fratocchi et al., Citation2016; Krenz et al., Citation2021). The factors internal to the firms, usually focused on their motivations and strategies, include the ‘made in’ effect, pursuing social and environmental goals, moving production closer to domestic customers and markets, the need to increase the quality of production and reduce delivery time, strengthening process and product innovation, global reorganisation of the firm, and the diversification of supply chains (Barbieri et al., Citation2018; Dikler, Citation2021; Fratocchi et al., Citation2016; Fratocchi & Di Stefano, Citation2019).

These findings suggest that reshoring can be explained in part by more favourable conditions in the home country. In some circumstances, therefore, reshoring might be expected to have a positive effect on the performance of reshoring firms. However, there is little research on how reshoring affects firm performance. This paper responds to this gap and analyses whether and when reshoring affects the productivity of manufacturing firms. I used data from the European Reshoring Monitor (ERM), which provides information on the relocation of a sample of European firms in the period 2014–18. The main findings suggest that reshoring increased productivity in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), especially when they repatriated production from distant and developing countries, such as Asian countries. This positive effect was not seen in large firms or firms repatriating production from more developed countries in America and Europe.

This paper contributes to the reshoring literature by shedding new light on the impact of reshoring on firm performance. The analysis also shows that reshoring strategies are important for SMEs, but previous studies have mainly focused on large and multinational companies. Lastly, this analysis provides a quantitative assessment of the effect of reshoring at the firm level. Previous studies (e.g., Pegoraro et al., Citation2022) have mainly analysed the determinants and effects of reshoring at the macroeconomic level, or using anecdotal evidence and qualitative methodologies.

2. EMPIRICAL ANALYSIS

2.1. Data sources and sample

In this study, I used two sources of data. The first was the ERM, a EurofoundFootnote1 initiative that aims to identify the reshoring of manufacturing and other value-chain activities to the European Union (EU). ERM used several sources of data including media, specialised press, and scientific literature to collect information on European firms that reshored manufacturing in the EU during the period 2014–18. It identified a total of 253 cases of reshoring. The number of cases remained quite stable in 2013 and 2014 (12.5% and 11%, respectively), was more than double in the following two years (29% in both) and decreased again in 2018. Back-shoring was the main strategy for firms in the database (92%). In terms of firm size, large firms accounted for around 59% of all cases, and the remaining 41% were SMEs. The countries with the highest number of cases of reshoring were the UK (44), Italy (39) and France (36). The countries left during the reshoring process were mainly China (30% of cases), India and Poland (both 6%). More than 85% of reshoring cases occurred in the manufacturing sector, followed by information and communication technology, and financial and insurance services. Within manufacturing, the most affected sector was clothing (around 11%), followed by food products and machinery and equipment.

The second source of data is the AMADEUS business database by Bureau van Dijk, which was used to obtain balance sheet data for the firms in the ERM database. From the list of firms in the ERM, I retained only the manufacturing firms. I lost some firms in the merging process between the ERM and AMADEUS. The final sample for analysis was therefore 102 firms that completed reshoring in the period 2014–18, and for which balance sheet variables for the three years before and after reshoring were available.Footnote2 The final sample was a panel of 102 European manufacturing firms observed for seven years.

2.2. Methodology

The empirical analysis used econometrics with a baseline model specification of:

(1)

(1) where i and t indicate firms and years,

is the vector of controls that vary across firms and over time,

is the vector of controls that vary across firms but are constant over time,

are time-fixed effects that control for time-varying unobserved heterogeneity, and

is the random error term that captures all remaining effects. The dependent variable of the model is

, which measures total factor productivity (TFP) at the firm level. According to Seker and Saliola (Citation2018), TFP was computed as the residual from estimating the log transformation of the following Cobb–Douglas production function:

where

is annual sales,

is annual labour costs,

is the cost of intermediate goods, and

is the TFP term.

The explanatory variable of interest was Reshoring, a binary indicator equal to 1 for the year of reshoring and the three subsequent years, and 0 for the years before reshoring. The coefficient of interest was , which measured the impact of reshoring on firm TFP.

The controls in were firm age (variable Age), the number of years from firm foundation, and firm size (Size), as total assets. The controls in

were the binary indicator Back-shoring, which equalled 1 if production was moved back to the home country and 0 if in a neighbouring country; dummies for the countries where production was previously located (Country reshoring dummies); dummies for the countries where firms are headquartered (Country origin dummies); and dummies for the firm sector of activity (Sector dummies). The model was estimated using ordinary least squares. To check robustness, the model was also estimated using fixed effects (see Table A1 in Appendix A in the online supplemental data), but this could not include time invariant controls.

2.3. Results

shows the first set of estimates. The first column shows the model for all firms in the sample. The variable Reshoring was not statistically significant. After splitting the sample into two (large firms, with more than 250 employees and SMEs, with fewer than 250 employees), reshoring was positively and significantly associated with TFP of SMEs, but not large firms. The controls suggest that SMEs with higher productivity prefer backshoring rather than nearshoring and that productivity increases with firm size.

Table 1. Effect of reshoring on firm total factor productivity (TFP).

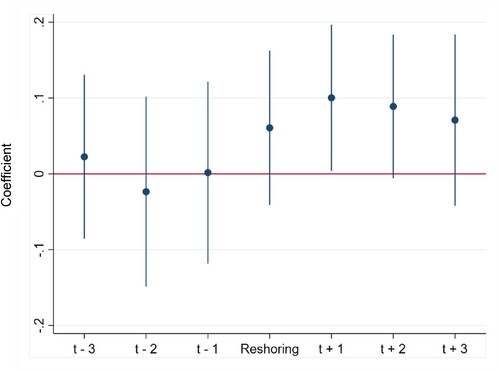

An issue that can arise in these estimations is the presence of trends of TFP before reshoring. In the second step, focusing only on SMEs, I used an event study approach to rule out this possibility. This methodology is widely used to test for the presence of pre-trends and analyse the dynamics of a relationship between variables (MacKinlay, Citation1997). shows the estimated coefficients and associated confidence intervals for the impact of reshoring in each year, before and after the actual year of reshoring, based on the model specification in . Before reshoring, there is no reason to expect that the coefficients significantly influenced firm TFP. I would therefore expect the estimated coefficients before reshoring not to differ systematically from 0. shows that in the three years before reshoring, the coefficients did not have a clear trend and were not statistically different from zero. They became statistically significant in the years immediately after reshoring, especially years t + 1 and t + 2. The increase in TFP was higher in these years. This analysis therefore suggests that there were no pre-trends in TFP and that the impact of reshoring was mainly seen in the first two years.

Figure 1. Event study for the impact of reshoring on small and medium-sized enterprises’ (SMEs) total factor productivity (TFP).

Lastly, in , I examined whether the positive effect of reshoring on TFP depends on the location where manufacturing activities were offshored. These locations were grouped into four geographical areas: Asia, Europe, United States and the Mediterranean area. For each geographical area, a binary indicator was included in the model (Asia, Europe, USA and Mediterranean area) and interacted with the Reshoring variable (variable Interaction in ). The variable Interaction, therefore, is the interaction between: Reshoring and Asia in column (1); Reshoring and Europe in column (2); Reshoring and USA in column (3) and Reshoring and Mediterranean area in column (4). To save space, the controls are not shown but all regressions included the same set of controls as in .

Table 2. Reshoring and total factor productivity (TFP) of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) for different locations of previous offshoring.

The binary indicators for the geographical areas were not statistically significant, suggesting that TFP of SMEs was not systematically different across destination areas. The coefficient of Interaction was positive and significant in column (1) but negative in column (3). These results suggest that TFP increased more for SMEs moving manufacturing activities back from Asia than from other locations.Footnote3 TFP also decreased for SMEs reshoring activities from the United States compared to those relocating from other geographical areas.

3. CONCLUSIONS

This paper provides empirical evidence that reshoring may have a positive impact on firm productivity. The gains in productivity were not seen in all reshoring cases but limited to manufacturing SMEs, especially for those that repatriated production to advanced economies from some countries in Asia.

These insights have important implications for policymakers aiming to enhance SMEs and regional competitiveness. Several developed countries, including the USA and the UK, have taken the view that reshoring will foster regional employment in the home country, as well as regional competitiveness and resilience in more developed regions (Nujen et al., Citation2019). They have therefore implemented important policies to support the repatriation of manufacturing activities (Elia et al., Citation2021). Building on these experiences, other countries are considering introducing similar national policies. However, it is important that policymakers understand the mechanisms underlying supply chain dynamics and which firms benefit more from the repatriation of production. This paper has highlighted that the highest increases of productivity are seen in SMEs that repatriate manufacturing activities previously offshored in Asia. Even where SMEs are the backbone of the economic system – the case in several developed countries – their relocation strategies are underestimated by both the literature on reshoring and policymakers (Canello et al., Citation2022). Policymakers should be aware that reshoring can be a good opportunity for SMEs and for the regions in which they relocate production. When reshoring, SMEs are more likely than large companies to choose their home country; large firms often consider other foreign locations (Rasel et al., Citation2020). Policymakers should therefore plan appropriate initiatives and incentives to support and attract SMEs reconfiguring their value chain at both national and regional level. Reshoring can offer many benefits to the local economy. By creating jobs in the home country, it can help to stimulate economic growth and reduce unemployment. It can also help to revive declining industrial regions and bring new investment to these areas.

This analysis had some limitations that call for future research. First, the size of the sample was relatively small. Future studies could collect further data to provide more robust evidence. A common issue for research on reshoring is that quantitative data at the firm level are scarce. This analysis, however, has the merit of being among the first to assess the impact of reshoring on firm performance by using micro-data at the firm level. Second, the paper did not consider the motivations underlying reshoring. One of the main results is that the gains in firm productivity were higher when reshoring from Asia. A research report by Eurofound suggests that this is because in recent years, firms that offshored their manufacturing activities to Asia have experienced some issues with product quality, intellectual property rights and sustainability, and because production and logistics costs have significantly increased (Eurofound, Citation2019). In this quantitative analysis, I did not investigate the motivations for reshoring and future studies could explore this point, especially for the firms that achieved the greatest gains in productivity. Further research is also needed to identify other relevant factors that make a reshoring strategy appealing for firms.

Lastly, the empirical analysis may suffer from endogeneity issues to the extent that reshoring decisions depend on firm performance, especially on firm productivity changes. The empirical model used here cannot completely rule out the problem of endogeneity, but I tried to avoid omitted variable issues by considering important time-varying controls at firm level, as well as fixed effects at firm/country/year levels to account for unobserved and time invariant heterogeneity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.7 KB)DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Eurofound is the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions of the European Commission.

2 Some of the 253 reshoring cases included in the ERM database were completed in 2019. I did not include them in this analysis because firms’ balance sheet data were only available to 2021, and three years of data following reshoring were needed to assess its impact on firm productivity.

3 Asian countries included in the sample were China, Bangladesh, India and Vietnam.

REFERENCES

- Ancarani, A., Di Mauro, C., & Mascali, F. (2019). Backshoring strategy and the adoption of industry 4.0: Evidence from Europe. Journal of World Business, 54(4), 360–371. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2019.04.003

- Barbieri, P., Boffelli, A., Elia, S., Fratocchi, L., Kalchschmidt, M., & Samson, D. (2020). What can we learn about reshoring after Covid-19? Operations Management Research, 13(2020), 131–136. doi:10.1007/s12063-020-00160-1

- Barbieri, P., Ciabuschi, F., Fratocchi, L., & Vignoli, M. (2018). What do we know about manufacturing reshoring? Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 11(1), 79–122. doi:10.1108/JGOSS-02-2017-0004

- Canello, J., Buciuni, G., & Gereffi, G. (2022). Reshoring by small firms: Dual sourcing strategies and local subcontracting in value chains. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(2), 237–259. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsac015

- Dikler, J. (2021). Reshoring: An overview, recent trends, and predictions for the future. KIEP Research Paper, World Economy Brief 21–35. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3916557

- Elia, S., Frantochi, L., Barbieri, P., Boffelli, A., & Kalchschmidt, M. (2021). Post pandemic reconfiguration from global to domestic and regional value chains: The role of industrial policies. Transnational Corporations Journal, 28(2), 67–96. doi:10.18356/2076099x-28-2-3

- Eurofound. (2019). Reshoring in Europe: Overview 2015–2018. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Fratocchi, L., Ancarani, A., Barbieri, P., Di Mauro, C., Nassimbeni, G., Sartor, M., Vignoli, M., & Zanoni, A. (2016). Motivations of manufacturing reshoring: An interpretative framework. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 46(2), 98–127. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-06-2014-0131

- Fratocchi, L., & Di Stefano, C. (2019). Does sustainability matter for reshoring strategies? A literature review. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 12(3), 440–476. doi:10.1108/JGOSS-02-2019-0018

- Krenz, A., Prettner, K., & Strulik, H. (2021). Robots, reshoring, and the lot of low-skilled workers. European Economic Review, 136, 103744. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103744

- MacKinlay, A. C. (1997). Event studies in economics and finance. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(1), 13–39. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2729691

- McIvor, R., & Bals, L. (2021). A multi-theory framework for understanding the reshoring decision. International Business Review, 30(6), 101827. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101827

- Nujen, B. B., Mwesiumo, D. E., Solli-Sæther, H., Slyngstad, A. B., & Halse, L. L. (2019). Backshoring readiness. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing, 12(1), 172–195. doi:10.1108/JGOSS-05-2018-0020

- Pegoraro, D., De Propris, L., & Chidlow, A. (2022). Regional factors enabling manufacturing reshoring strategies: A case study perspective. Journal of International Business Policy, 5(1), 112–133. doi:10.1057/s42214-021-00112-x

- Rasel, S., Abdulhak, I., Kalfadellis, P., & Heyden, M. (2020). Coming home and (not) moving in? Examining reshoring firms’ subnational location choices in the United States. Regional Studies, 54(5), 704–718. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1669784

- Seker, M., & Saliola, F. (2018). A cross-country analysis of total factor productivity using micro-level data. Central Bank Review, 18(1), 13–27. doi:10.1016/j.cbrev.2018.01.001

- Stentoft, J., Mikkelsen, O. S., Jensen, J. K., & Rajkumar, C. (2018). Performance outcomes of offshoring, backshoring and staying at home manufacturing. International Journal of Production Economics, 199, 199–208. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.03.009