ABSTRACT

In the period after the 2008 financial crisis, the European Union and Brazil experienced, respectively, periods of regional divergence and convergence. The research developed in these two territories brings new evidence on the importance of non-territorial policies, that worked as indirect regional policy, for these trajectories. In the case of the EU, (direct) regional policy was not strong enough to counteract more non-territorial policies that acted in favour of divergence. In the case of Brazil, the absence of a relevant direct regional policy did not prevent convergence, since the government adopted a set of non-territorial sectoral policies that functioned as indirect regional policy. This is particularly relevant in the current European context, where prolonged social and economic stagnation or decline in many regions has been the source of discontent that is expressed electorally.

1. INTRODUCTION

Regional development, understood as an increase in the productive capacities and improvement in the well-being of the populations of territories on a subnational scale, has been discussed mainly in terms of objectives and policies designed specifically for territories at this scale. In recent decades, the importance of non-territorial (sectoral) policies for the development of regions and for the convergence or divergence between them has been largely neglected in the West (Parr, Citation2015). The lack of concern with this type of policy in regional development literature, which is also known as ‘indirect regional policy’ or ‘implicit regional policy’ (the latter, in Brazil), is a shortcoming that this article aims to address, whilst acknowledging that this is only one of several aspects of regional policy that have been neglected (Parr, Citation2015).

Positioning ourselves within this framework, we try to answer the following research questions: What were the most important policies for the convergence/divergence dynamics in the EU and Brazil after the 2008 financial crisis? Is there a need for regional development studies and regional policy to pay more attention to non-territorial policies that function as indirect regional policy? Initially, we had only direct regional policy in mind. As the research progressed, we realised that in both cases direct regional policy had been of secondary importance to other policies – non-territorial sectoral policies that had functioned as indirect regional policy. This led us to broaden the focus of the research, with the aim of understanding which non-territorial sectoral policies had been most important in the EU and Brazil, and how they had acted.

To identify regional dynamics, a regional development index was built, using economic, social and demographic variables. The results of the study are also based on a qualitative approach, which made it possible to obtain information on the design, implementation and results of the policies, identifying successes and shortcomings.

Investigating and analysing regional dynamics and policies in the EU and Brazil to advance knowledge in this field may not seem an obvious choice, as they are spaces with significant differences in terms of the average level of development and institutional structures. However, what we analyse is not so much the institutional structures and procedures or the levels of development, but rather the direction of the results obtained in relative terms (convergence or divergence) as well as the general logic of the main policies in force. In addition, because we want to underline both the role of direct and indirect regional policies, it is didactic to use contrasting processes and strategies, as it is the case with the EU and Brazil. Finally, we intend to go beyond the Western-centred political-institutional and conceptual framework by incorporating Brazilian cases and references, namely in the field of indirect regional policies.

With a few exceptions (e.g., Garretsen et al., Citation2013), in European literature, indirect regional policy and its role on regional inequalities is not a frequent topic of analysis, even if a relationship has been established between divergence and policies linked to globalisation and European integration. In other words, they function as indirect regional policy. The risk ‘of a counter-treatment effect on overall economic growth, whereby one policy area may counterbalance the pro-cohesion effects of the other’ (Crescenzi & Giua, Citation2016, p. 2343) is occasionally referred to in the literature, but this has not been reflected into empirical analyses that show whether these contradictory effects may end up jeopardising the convergence of EU's NUTS2 regions.

In the case of Brazil, there is a certain tradition of discussing indirect regional policy. In relation to the large north and northeast regions, the poorest in Brazil, it has been recognised that ‘the impacts produced by broader national policies – such as transport infrastructure, energy, communications, housing etc. – affect in much more relevant magnitude the regional trajectories and dynamics than simply the explicit regional policies’ applied since the mid-1950s (Neto et al., Citation2017, pp. 38–39). In this article, we demonstrate that this has remained true after the 2008 financial and economic crises.

In the European case, the divergence registered after 2008 at the NUTS2 level is part of a broader problem of divergent regional trajectories, which are related to the contemporary globalisation, characterised by the territorial agglomeration of economic activities (Hadjimichalis, Citation2018; Vale, Citation2012). In a first phase, starting in the 1990s, this caused divergence within countries (Farole et al., Citation2009), but at the EU level there was convergence, with the improvement of indicators of the poorest countries in the South and then in the East. After the 2008 crisis and its aftershocks in the eurozone, divergence occurred at the EU NUTS2 level.

In this period, the EU had a strong cohesion policy in terms of budget and regulatory framework, but other policies acted in the direction of divergence, with the eurozone crisis being a key force in this direction. In the case of Brazil, we found that direct regional policy was very weak and that it was mainly non-territorial sectoral policies that brought about convergence. It should be noted that the existence of thematic areas of cohesion policy that overlap with some of Brazil’s non-territorial sectoral policies (notably the infrastructure investments financed by the Growth Acceleration Plan) is not contradictory to the fact that they are, respectively, direct regional policy and indirect regional policy. The distinction between the two does not stem from thematic priorities. It stems from the fact that direct policy is aimed at specific territories/regions, while indirect policy is aimed at the whole territory/country, using territorially uniform criteria.

In the next section, we revisit the key ideas underpinning regional development policies since the second half of the last century, as well as the main policy approaches applied and its neglected aspects. Section 3 summarises the methodology used in the research and Sections 4 and 5 present the results, respectively for the EU and Brazil, regarding regional development dynamics in the 2008–14 period and the policies that most influenced them. In Section 6 we present the implications of these results and suggest contributions to future policy approaches.

2. THE USEFULNESS OF REGIONAL POLICY AND ITS MAIN NEGLECTED ASPECTS

When discussing the implications of non-territorial sectoral policies for regional convergence/divergence, we should bear in mind the reasons why it was originally considered desirable to have a regional policy and what were its main objectives. The initial justification for regional development policies was rooted in two aspects that appear intertwined: the need to increase well-being in the lagging regions and, simultaneously or because of this, to generate efficiency gains in the national economy and increase its potential for growth (Martin, Citation2015; Parr, Citation2015).

In post-World War II Western Europe, this happened in a context in which a regional problem was identified: the unequal growth rates of the regions, leading some to develop rapidly and others to lag. In that period, this was considered worthy of correction, to strengthen the well-being of the populations of less developed regions. This concern is related to the ideas of well-being and social justice, but with a spatial dimension – which in recent literature sometimes falls within the scope of spatial justice (Madeira & Vale, Citation2015; Soja, Citation2010).

Based on these ideas, from the 1950s onwards, regional development policies began to aim for greater equity and balanced development between regions in OECD countries, in a context dominated by strong industrialisation accompanied by increasing regional inequalities (OECD, Citation2010, p. 11). These policies aimed at greater use of the work force and higher income in regions considered to be problematic. To this end, they employed redistributive measures to induce an increase in demand that would hopefully be long-lasting.

The type of intervention in regional economies pursued at that time can be seen as an extension of the universalist policies of state intervention in the redistribution of wealth and support for the provision of basic services with identical standards, so that it was possible to ensure a minimum standard of living in the country and tackle inequality. But these ideas lost momentum and a new type of regional development policy began to take hold in the 1970s and 1980s. The production crisis and the problems experienced in some key sectors were enhanced by the oil shocks of the 1970s and led to major unemployment problems which were unevenly distributed in space. This led, in turn, to the introduction of a new dimension to regional development policy: explicitly combating unemployment (OECD, Citation2010, pp. 11–12), which was not necessarily concentrated in lagging regions.

Since then, national governments increasingly privileged the goal of regional growth, over that of redistribution, in pursuit of national and regional competitiveness. This was pushed to the point where this idea of competitiveness came to clearly dominate policy approaches to regional development (Bristow, Citation2009), with EU cohesion policy also evolving in this direction (Tomaney et al., Citation2010). It was in this way that ‘a general policy shift towards support for endogenous development and the business environment, building on regional potential and capabilities, and aiming to foster innovation-oriented initiatives’ was justified (OECD, Citation2010, p. 12). Thus, the new paradigm replaced the original main objective, which was to achieve less inequality through balanced regional development, with that of simultaneously achieving greater competitiveness and equity – the new designation for ‘less inequality’ or ‘greater equality’.

The pre-eminence of competitiveness over equity went more or less hand-in-hand with the rise of the influence of the ideas of the ‘New Economic Geography’ (NEG). In accordance with this perspective,

spatial concentration of economic activity will increase national growth as a result of economies of scale, knowledge spillovers, and local pools of skilled labour resulting in productivity gains. Accordingly, policies that aim to spread growth amongst regions are deemed to run counter to the natural growth process and are unjustified on efficiency grounds, unless significant congestion costs exist. (Tomaney et al., Citation2010, p. 775)

Taking into consideration this evolution in regional policy focus, a strong reason for evoking the importance of indirect regional policy in the current context is that the regional policy paradigm that has been in force coincides with a worsening of regional inequalities in some geographical areas, such as several European countries and the US. Therefore, it becomes relevant to address the distinction between direct regional policy and indirect regional policy (which can also be called ‘explicit’ and ‘implicit’ regional policy, as is the case in Brazil), with a focus on the relevance that the latter has for the dynamics of convergence or divergence.

Direct regional policy (usually referred to just as ‘regional policy’) is specifically aimed at one or more regions of a country which need help to bring their socio-economic development in line with that of the average or better off regions. Thus, the basis on which regional (development) policy was established historically makes it clear that this was direct regional policy. Examples correspond to the construction of infrastructure, oriented vocational training, attraction of new enterprises through tax benefits or support for technological innovation in the regions specifically targeted by regional policies (Pike et al., Citation2007).

Indirect regional policy does not target specific territories and therefore it is part of non-territorial sectoral policies. However, their impacts vary depending on the development levels of the regions, and they have differentiated effects on the development trajectories of the various regions of the territory for which they are designed and implemented – usually countries, but they can also be applied to groups of countries, as in the case of the EU. Indirect regional policy is usually more based on budgetary transfers from the government, namely when they subsidise people in certain situations or ensure public services with a given standard; but it can also be exercised through automatic stabilisers (such as unemployment benefits) and some expenditures inherent to the functioning of the state. We can also think of policies in the field of international economic relations, such as those adopted in the context of neoliberal globalisation (Ezcurra & Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013), or more specifically in the field of international trade (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2012). And there is monetary policy itself, particularly in the case of the EU, whose characteristics can affect its various regions asymmetrically (De Grauwe, Citation2011; Rodrigues & Reis, Citation2012). In reality, all these policies may affect the development of regions, contributing to convergence or divergence at the EU level.

The growth of regional inequalities in the EU has been associated with various processes, sometimes linked to the political economy of globalisation (Madeira, Citation2014). With a major fall in industrial activity and employment levels in many places, stagnation or even reduction in wage levels for part of their populations, there is no prospect of the situation being reversed in the current context. These are mainly regions of small- or medium-sized industrial cities, as well as their suburbs and surrounding rural areas (Martin et al., Citation2018, p. 9).

In territories where these problems assume greater proportions, as in the case of poor areas or areas in prolonged decline, there is sometimes a feeling among the populations that they do not count for political power. This has generated what can be seen as electoral revolts, in which there are significant votes for anti-establishment parties. This is one of the reasons why the nationalist right has grown in Europe – a phenomenon that can be seen as the revenge of the places that do not matter, against the feeling of being left behind (MacKinnon et al., Citation2022; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

The increase of regional imbalances, to the point of threatening political stability, highlights the importance of the regional question and of the shortcomings of the direct regional policy. This justifies bringing to the fore some neglected issues, such as indirect regional policy – or regional policy that is implicit in non-regionalised policies.

3. METHODOLOGY

To study the role of regional policies after the 2008 crisis, we analysed the evolution of regional development inequalities in the EU and Brazil, as well as EU cohesion policy and direct regional policies in Brazil, and non-territorial (sectoral) policies with relevant impacts on regional inequalities. The study of two spaces with very different policy approaches to regional development in the same period (2008–2014) allowed us to see the role of indirect regional policies and how these worked in opposite directions.

The suitability of comparing regional development dynamics and policies in the EU and Brazil may raise doubts, since they are areas with different characteristics. From a geographical point of view, this is not problematic since both have territorial and demographic scales of the same magnitude. Additionally, both have socio-economic centres and peripheries, where the question of the need for convergence arises.

With regard to the institutional and normative framework, there are also differences, but this did not prevent the identification and analysis of the logic behind the policies applied and establishing their main results. Both in the EU and in Brazil there were direct regional development policies and non-territorial sectoral policies that functioned as indirect regional policies, even if in the case of the EU they were not recognised as such (Madeira, Citation2019). Thus, both in the EU and in Brazil it was possible to identify divergence/convergence dynamics and relate them to the main policies that produced these dynamics. This relation was established based on fieldwork carried out in regions of the EU and Brazil (see below).

For the analysis of the evolution of regional inequalities, a regional development index (RDI) was calculated for the EU and another for Brazil, using eleven variables of economic, social and demographic nature (Madeira, Citation2019, pp. 172–175 and 179–183). The set of variables used in each case is not entirely coincident, though very similar (see Annex A in the online supplemental data). This is either because the same set of variables was not available or because the differences in the two socio-economic realities sometimes justify the use of different variables to measure the same dimensions of development and well-being. For example, households with sewage constitute a meaningful indicator for differentiating development in Brazil, but this is not the case for the EU. GDP per capita in purchasing power parities was used as an indicator for the EU, while GDP per capita without PPPs was used for Brazil, because here price differences between regions are smaller than within the EU and occur mainly between urban and rural areas. This does not mean that there are not important price differences within Brazil, including those between metropolitan regions (Almeida & Azzoni, Citation2016).

The construction of the two RDIs was inspired by the ideas underlying the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) for the calculation of its Human Development Index (HDI), adopting its method of normalising the used variables (UNDP, Citation2014). In the case of the EU, the indicator was calculated for its European NUTS2 regions, because its cohesion policy is designed and applied primarily at this scale, with some exceptions relating to some relatively small programmes. For Brazil, the calculation was at the level of its federated states, because this is where we find greater regional identity and they are also the ones that apply the main national/federal policies, namely those that in this period had more impact on the evolution of its development.

The RDI was calculated for 2002, 2008 and 2014. This made it possible to calculate its variation in the years before and after the crisis, as well as the respective coefficient of variation, to establish the dynamics of convergence/divergence before 2008 and determine whether it remained the same or has changed following the crisis. The RDI values in 2008 and their respective variations in 2008–14 were mapped using ArcGis, which automatically divided the series into classes, according to Jenks’ natural rupture clustering method. In the maps concerning RDI variation in the 2008–14 period, the five classes obtained vary from strong relative losses to strong relative gains (O’Brien & Leichenko, Citation2003).

In the next step, for both the EU and Brazil, we identified the direct regional development policies in place and the institutional structures involved in their implementation. We also identified the dominant concepts and strategies in each of these two territories, by drawing on literature, policy documents and fieldwork in regions of the EU and Brazil from January to October 2017. This qualitative approach complemented the quantitative approach of the previous stage of the research, as it made it possible to identify the policies in place (especially in the case of Brazil), as well as how they were implemented and their main results in those regions. It also allowed us to identify the main non-territorial sectoral policies (working as indirect regional policy) that in that period were important for the evolution of regional inequalities in each of the territories.

The fieldwork in the EU was carried out in the Spanish Extremadura, a poor region in the European context. In Brazil, it was conducted in Paraíba and Santa Catarina, a poor region and a developed region, respectively, in the Brazilian context. One of the authors was based in each of these regions for three months, at local universities that supported the fieldwork. The policies that were considered in this study result from the literature review, from documentary research and from a set of interviews carried out during the fieldwork, as part of one of the author’s PhD thesis’ (Madeira, Citation2019). Academic specialists, technical experts and politicians from the regions studied were interviewed. They were chosen and contacted with the help of the professors who supported the fieldwork at these universities. For the EU case, the cohesion policy was also analysed from the official documents available on the European Commission website. Its application and possible limitations in convergence objective regions was studied through fieldwork in Spanish Extremadura. Here, the analysis of the regional policy documents in force specifically in the region (deriving from what was stipulated by the cohesion policy in the period 2007–13) made it possible to identify the regional priorities and objectives.

It is worth mentioning that it is easier to get information online about European cohesion policy, based on the DG Regio page on the Commission’s website, than it is about the set of Brazilian policies dispersed among various ministries – which sometimes have their information removed by subsequent governments. That’s why we think it’s more important in this article to detail Brazilian regional policy than European policy. In addition, the latter is more familiar to the European public.

4. DIVERGENCE AND POLICIES IN PLACE IN THE EU

4.1. Lagging southern regions losing out and central regions gaining

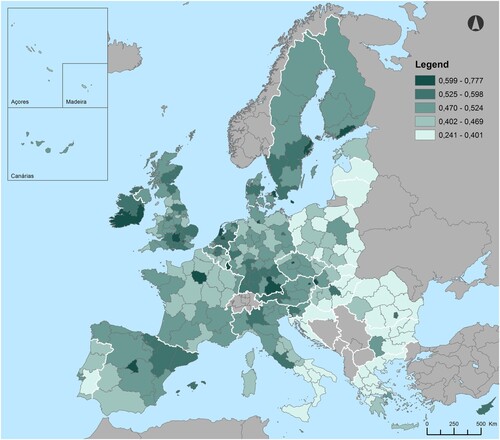

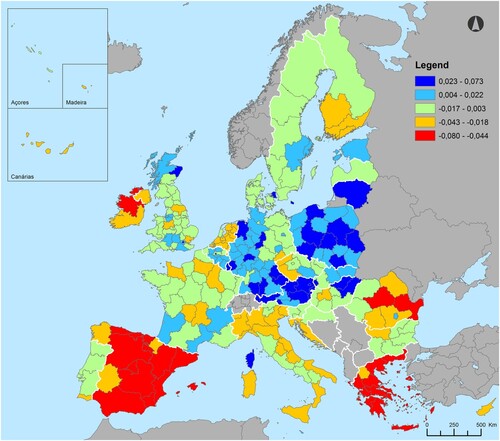

In the EU, the RDI decreased 0.005 points between 2008 and 2014 (from 0.491 to 0.486) which shows that there was a small average decline in development and well-being in the EU as a whole. Over this period, the RDI declined in 15 of its 28 countries and in 100 of its 266 European NUTS2, with important differences between territories. The coefficient of variation (CV) of the RDI of these NUTS2 rose from 0.160 to 0.180 between 2008 and 2014, showing a clear regional divergence. A vast majority of the losing regions after 2008 are concentrated in the less developed areas of the south, with lower RDI values, and also in Ireland, as shown by the relative evolution of the respective RDIs ( and ; ).

Table 1. EU RDI between 2002 and 2014.

Figure 1. Regional development index (RDI) in the EU in 2008.

Source: Eurostat; authors’ calculations.

Figure 2. RDI change in the EU, 2008–2014.

Source: Eurostat; authors’ calculations.

Many of the NUTS2 regions in the more developed central and northern EU countries were winners in relative terms over the same period. This pattern is evident in Austria and Germany, but also occurred in several regions of France and the UK. In the case of Germany, the winning dynamics are strong in its western and southern regions (corresponding to the former FRG) and weak in those of the former GDR. In the east, there is a large cluster of winning regions, covering the whole of Poland, some Slovak, Czech and Hungarian regions as well as Lithuania and Estonia.

This pattern of regional dynamics after 2008 represents a reversal from what had happened in the previous years, between 2002 and 2008, when many richer regions in the north and centre had relative losses, while many in the south and almost all in the east had gains in relative and absolute terms (Madeira, Citation2019, pp. 204–209). This allowed a strong convergence of NUTS2, both in terms of RDI and GDP/inhab (European Commission, Citation2017, p. 5).

The fact that after 2008 the losing regions were heavily concentrated in the south (), many of which had levels of development and well-being below the EU average, means that there was divergence of poor regions there. On the other hand, the fact that the winning regions in this period were largely concentrated in the centre and north means that there was also divergence of rich regions (in the sense of moving away from the average). Together, these two territorial patterns are the main expressions of the divergence of NUTS2 regions throughout the EU.

4.2. Insufficient regional policy with the euro as a divergence factor

The direct regional policy in force in the EU in the period under review is essentially that of the 2007–2013 programming period of the cohesion policy, whose implementation covers the period from 2008 to 2014. After the 2000 Lisbon Strategy was adopted, it was decided that countries should implement it also through the cohesion policy for this period, which meant that most of its resources were used for growth and jobs, assumed as policy priorities. These priorities materialised in aspects such as more investment in knowledge and innovation, stimulating business potential (especially of SMEs), improving employability through flexicurity and better management of energy resources. It was stipulated that interventions co-financed by the funds would focus on competitiveness and employment priorities and that the Commission and member states should ensure that 60% of the expenditure under the Convergence objective (covering less developed regions) and 75% of the expenditure under the Competitiveness and Employment objective (covering more developed regions) was allocated to these priorities (European Council, Citation2006).

Two other policies also contributed in a relevant way to the evolution of regional inequalities in this period. The policy of large openness to foreign trade in the framework of neoliberal globalisation was one of them. Ezcurra and Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2013) concluded that countries with higher levels of integration with the world economy tend to have higher levels of regional inequality. In the case of the EU, the European Commission (Citation2007) found a relationship between the entry of developing countries into industrial markets in the context of globalisation and the vulnerability of many European regions, particularly those specialising in low-cost production – typically the least developed and with the lowest levels of welfare.

Monetary policy also contributed to the worsening of regional inequalities in the EU in this period. This happened because the euro was created without the countries that adopted it forming an optimal currency area (OCA), also due to regional imbalances (Martin, Citation2001), making it difficult to achieve convergence within the euro zone. Additionally, the institutional architecture of the euro zone itself (De Grauwe, Citation2011), the policy of overvaluation in relation to the needs of the southern countries (Hadjimichalis, Citation2011; Vale, Citation2014) and the fiscal austerity approach applied based on euro zone rules (Rodrigues & Reis, Citation2012) contributed decisively to the euro becoming a major source of territorial divergence within the EU. Events and biases ensuing the crisis that began in 2008 ‘are also at the root of the trajectory of uneven development, expressed in the new salience of a core–periphery divide’ (Rodrigues & Reis, Citation2012, p. 189).

In a context where regional convergence was no longer the ultimate goal of European regional and cohesion policy (Vale, Citation2014), it is not surprising that this policy was not strong enough to compensate the most fragile regions at a time of acute crisis. Thus, regional divergence in the EU between 2008 and 2014, partly resulting from the decline of many poor southern regions, corroborates Thirlwall’s (Citation2000) idea that it would be very unlikely that European regional policies would be strong enough to compensate for divergence forces in the event that countries were hit by adverse shocks.

The Structural and Cohesion Funds acted as a mechanism for interregional stabilisation, but their total amount, despite being significant and constituting one of the main headings of the EU budget, is short for the objectives to which these funds should respond, especially in acute crises, as has long been recognised (Martin, Citation2001; Thirlwall, Citation2000; Vale, Citation2014). Thus, cohesion policy was insufficient to counterbalance the forces of divergence unleashed after 2008, which reinforced those that already existed, in the context of globalisation and the euro. In Extremadura, in this period, the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) had a smaller contribution than usual (Madeira et al., Citation2021; Ramajo et al., Citation2014), due to the difficulties in co-financing on the part of the Junta de Extremadura or the Spanish Government. At the same time, the European Social Fund (ESF) was an important buffer against the social effects of the crisis.

5. CONVERGENCE AND POLICIES IN PLACE IN BRAZIL

5.1. Gains in poor states and relative stagnation in more developed regions

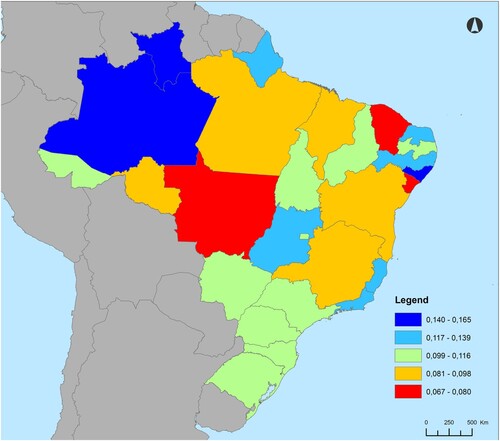

In Brazil, the RDI value rose from 0.467 to 0.574 between 2008 and 2014, indicating that this was a period of strong improvement of the economic and social situation in the country as a whole, meaning that the 2008 crisis did not have a strong impact on its development and well-being in the years that followed. At the level of its federated states, the convergence trend that was going on since the beginning of the century intensified in this period, with the coefficient of variation of the RDI of the state-regions falling from 0.284 to 0.225 ().

Table 2. Brazil RDI between 2002 and 2014.

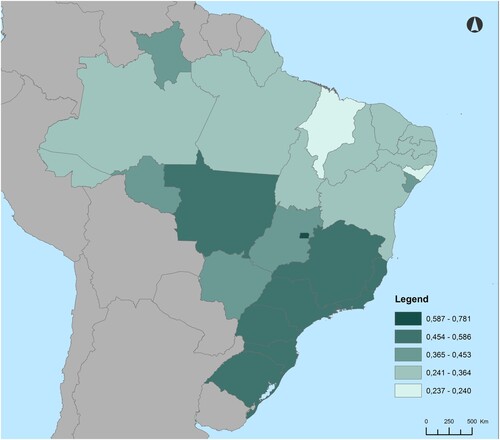

Over these six years, the value of the RDI increased in all Brazilian states, which means that in all of them there was an improvement in the socioeconomic situation and that convergence did not occur in a context that resulted in losses in the more developed states. The territorial pattern of development in Brazil is represented in , which shows that the states with the highest levels of development and well-being are concentrated in the south, while the poorest states (with RDI values below the average) are concentrated in the Amazonian north and in the northeast. This is a pattern that has persisted for more than a century.

Figure 3. Regional development index (RDI) in Brazil in 2008.

Source: IBGE, RAIS and Ipeadata; authors’ calculations.

shows that the relative gains (increase in RDI above the national average) occurred mainly in states of the northeast and north, although some of them registered relative losses. The majority of the more developed regions of the southeast and south showed an evolution close to the national average, with some few exceptions that offset each other. This means that regional convergence occurred due to the improvement of the indicators included in the RDI in a set of states in the north and northeast, mitigated by the divergence of some states in these two macro-regions.

Figure 4. RDI change in Brazil, 2008–2014.

Source: IBGE, RAIS and Ipeadata; authors’ calculations.

The convergence registered after the 2008 crisis, in a context of generalised socioeconomic improvement, followed a similar dynamic to that already in place in the previous period. Between 2002 and 2008, the value of the RDI increased by 0.097 points, from 0.369 to 0.467, in the whole country, while its CV fell 0.054 in the same period, which shows that there was convergence, which accelerated after 2008.

5.2. A limited direct regional policy and the convergence effect of some national policies

The Brazilian government conceived, at the beginning of the century, a new regional policy that, unlike the one implemented in previous decades, did not address the macro-regional scale. Instituted in 2007 under the designation of ‘National Policy for Regional Development’ (PNDR, in Portuguese), it was inspired by the experience of the European Union’s regional policy (Dąbrowski et al., Citation2018; Neto et al., Citation2017, p. 40). It was based on the idea of identifying and strengthening competitive advantages, aiming ‘at reducing inequalities in living standards between regions and promoting equity in access to development opportunities’ (Presidency of the Republic, Decree No. 6047/Citation2007).

The PNDR is of interest mainly for understanding that regional policy was a major objective of the Brazilian government of the time, even though it had almost no practical application. This happened because the Brazilian Congress approved this policy and then refused to approve the National Regional Development Fund (FNDR), which would have provided the resources required for its implementation. The government managed, however, to ensure that the constitutional funds targeting the most disadvantaged macro-regions (an inheritance from previous phases of Brazilian regional policy) started to address the priority areas defined in the PNDR (Amparo, Citation2014, p. 188).

Due to the absence of the main mechanism foreseen for its financing, the PNDR was applied in a very limited fashion. In this context, it is not surprising that the federal government has opted for alternative policies to accelerate the development of Brazil’s most disadvantaged regions and their convergence with the national average. This is how a set of non-territorial sectoral policies of national scope, especially concerning social welfare, ended up functioning as an indirect (or implicit) regional policy.

One of the main policies in this area was the transfer of income to the poorest segments of the population, which took place mainly through the Family Grant (Bolsa Família) Programme (PBF), but also through the Continuous Cash Benefit (Benefício de Prestação Continuada, BPC) and other related programmes with less financial expression. Created in 2003, the PBF distributed a monthly amount to families in a situation considered of extreme poverty or of poverty, covering the whole territory of Brazil. Naturally, the financial resources thus transferred had greater relative impact on the territories with higher rates of poor population, which typically were the least developed regions. Therefore, by covering a larger share of the population in the poorest regions than in the richest regions, Bolsa Família contributed more to the development of the former.

Following a similar logic, BPC paid a monthly minimum wage to disabled or elderly people (65 years or older) in households with per capita family income below 1/4 of the country’s minimum wage. Simultaneously, the Brazilian Government adopted a policy of valorisation of the minimum wage. These policies began in the first government of President Lula da Silva, starting in 2003, and were reinforced in his second mandate, along with others more focused on investment and consumption in response to the 2008 crisis. In the case of the minimum wage, in 2002 it represented 17.5% of the amount needed to meet the basic needs of a family of four, in 2008 covered 22% of those needs and in 2014, 26.3% (Madeira, Citation2019, p. 285). As in the case of Bolsa Família, both the BPC and the valorisation of the minimum wage contributed towards the acceleration of the development of the poorest Brazilian regions vis-à-vis the richest ones.

Investment policies were also pursued, which in some cases resulted in a higher relative allocation of resources to the poorest states, contributing to the convergence seen in this period, according to Neto et al. (Citation2017). This is the case of the expansion of the network of public universities and vocational and technological education to peripheral areas not previously covered (e.g., Carazza & Silveira-Neto, Citation2022). Simultaneously, in 2007, the federal government initiated the Growth Acceleration Plan (Plano de Aceleração do Crescimento, PAC), which then came to function as part of its anti-cyclical strategy; it had several editions, covering the entire period under study. The PAC essentially aimed at strengthening public investment, especially in infrastructure (roads, ports, airports), communications and housing (Programa Minha Casa Minha Vida), and was important for minimising the 2009 recession and in reducing regional inequalities. Some more specific policies, such as those targeting small-scale family farming, especially under the Ministry of Agrarian Development (MDA), also played a role in the development of poorer states (Amparo, Citation2014).

These investments were intended for the whole of Brazil and it was not possible to find data on the amounts spent in each federal state or macro-region. However, available information indicates that they were very important in the northeast macro-region: between 2007 and 2012 the main items of Brazilian public funds with an impact on regional development earmarked for the northeast macro-region grew 2.5 times compared to the period from 2000 to 2006, with an increase in the weight of the main social programmes (PBF and BPC), whose amount more than tripled between one period and the other (Neto et al., Citation2017, p. 43). The background scenario in the other macro-regions benefiting from direct regional policy (the north and the centre-west) was also one of a strong increase of resources in the same rubrics between the two periods.

This allows us to conclude that, from 2008 to 2014, regional convergence in Brazil happened mainly due to social programmes and some non-territorial sectoral policies, with Keynesian-type characteristics. These functioned as the main regional development policy that produced convergence – an indirect regional development policy. This happened because the government saw the reduction of regional inequalities as a central element of its strategy to reduce social inequalities in the country (Amparo, Citation2014, p. 185).

6. POLICY IMPLICATIONS

The research results showed that, after the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession of 2009, the dynamics of divergence in the EU and convergence in Brazil resulted, in both cases, mainly from non-territorial sectoral policies that overlapped with existing (direct) regional development policies. This points to the need to focus more on the issue of the relevance of indirect (or implicit) regional policies, which has barely been discussed in the specialised literature.

In the EU, the divergence that occurred at NUTS2 level between 2008 and 2014 did not happen because, but rather in spite of the direct regional development policy in place (cohesion policy). The Cohesion policy and the funds involved were not sufficient to counter the dynamics generated by the 2008 crisis, which ‘created a poor climate for investment and convergence’ (European Commission, Citation2016, p. 4). At the same time, from 2008 to 2014, some non-territorial sectoral policies in the EU acted towards regional divergence. Processes that were already in place from the past, linked to globalisation and increasing openness to international trade and, also, to the monetary logic underlying the euro, continued to act towards divergence. In the case of the euro, this was exacerbated by the austerity approach adopted to deal with the sovereign debt crisis of the most peripheral states, triggering dynamics that reinforced the forces acting towards divergence within it (De Grauwe, Citation2011).

A doubt that may be raised regarding the cohesion policy adopted in this period is whether the focus on competitiveness and its application to the whole EU does not decentre it from what is supposedly its priority – addressing the needs and disadvantages of the less developed regions and thus reducing the distances between different regions. This question arises because it is not clear that increasing competitiveness in all the regions of the EU is an efficient, or even effective, way of reducing the inequalities between them, even with much greater financial aid to the poorest regions than to the richest ones, as was the case in the period under review.

There is also evidence that the focus on competitiveness and, above all, innovation under the regional smart specialisation strategies (RIS3) adopted in the 2014–2020 programming period was a problem for the convergence of the most disadvantaged and peripheral regions of the EU (Barzotto et al., Citation2020; Madeira et al., Citation2021; Wigger, Citation2023). This was foreseeable already from a theoretical point of view (McCann & Ortega-Argilés, Citation2015) and was confirmed, for example, for the case of Spanish Extremadura, where up until 2019 convergence was limited and accompanied by population loss (Madeira et al., Citation2021). This is also supported by the conclusion of Crescenzi and Giua (Citation2016, p. 2352) that the favourable influence of European cohesion policy ‘is strongest in regions with the most favourable socio-economic environment and better overall economic performance’.

The development and implementation of such policies has relied on what can be described as ‘inadequate narratives about the experience of less-developed regions’ (Marques & Morgan, Citation2021, p. 475). The extensive literature review made by these authors led them to conclude that the role of the nation-state in the development of poorer and/or peripheral regions is crucial and that ‘understanding regional development as a collective endeavour should involve all geographic scales, including the nation-state but hopefully also international organizations’ (Marques & Morgan, Citation2021, p. 490). This leads them to argue that these two aspects deserve more attention than they have had hitherto – which corroborates the need to give more importance to indirect regional policy.

In Brazil, non-territorial sectoral policies mentioned above were central to explaining the convergence dynamics between 2008 and 2014, as direct regional policy was of little relevance. The historical trajectory of the country’s regional policy and its limited results may help to understand the Brazilian government’s choice, at the beginning of this century, to adopt a set of social policies and some other non-territorial sectoral policies aimed precisely at reducing regional inequalities, along with combating other inequalities. The positive results obtained by this approach in terms of convergence in this period reinforce the observation by Neto et al. (Citation2017) mentioned above: the impacts produced by national sectoral policies were more relevant to regional trajectories and dynamics than those of policies directly aimed at regional development.

Brazil had already previously experienced a reduction in regional inequalities related to non-territorial policies. Between 1995 and 2006, a set of nationwide non-territorial policies ended up functioning as indirect regional policy and contributed to the reduction of regional inequality in per capita income in this period (Silveira-Neto & Azzoni, Citation2011, Citation2012). These authors showed that while this reduction was related to the convergence of labour productivity across regions, it largely resulted from non-territorial policies involving income transfers through the Bolsa Familia programme and the increase in the purchasing power of the minimum wage.

The two cases studied and the different contexts in which they occurred, both from the point of view of the history of the respective regional policies and the development levels of their productive fabrics and well-being of their populations, show that the link between non-territorial sectoral policies and regional policy should be strengthened. In addition, both cases help to overcome the idea that non-territorial policies have little relevance from a regional perspective, which explains why indirect regional policy was one of the aspects identified by Parr (Citation2015) as being historically neglected in regional policy, and why it continues to be so. In the same vein, Crescenzi and Giua (Citation2016) concluded that non-territorial policies are key to maximising regional growth.

This issue is related to a broader debate on the fact that most policies have territorial incidences, which leads to the need to discuss the dichotomous distinction between sectoral policies and regional policies (Reis, Citation2015, pp. 113–114). From this perspective, non-territorial sectoral policies are considered the priority area for deliberation, with direct regional policy (or territorial policies in general) playing a supplementary or merely palliative role, which may not even be sufficient to compensate for the adverse effects of the former regarding spatial imbalances. In the two territories addressed in this article, this is also corroborated by the fact that, in both cases, the currently poorest regions have had this same characteristic since their respective regional development policies began to be planned and implemented, in the second half of the last century.

This justifies the questioning of direct regional policies and points to the need to adapt regional policy to the contexts and specificities of the regions, something that Iammarino et al. (Citation2019) have called the ‘place-sensitive distributed development approach’ when thinking on the various types of EU regions.

6.1. Some ideas on the ways forward

What happened to EU cohesion policy post-2008 is a useful example to illustrate the insensitivity of (direct) regional policies to the general environment in which they are implemented (Parr, Citation2015, p. 377). The 2007–2013 programming period had been designed for a macroeconomic framework of continuity with the previous period, which did not happen. In this context, the possibility of adapting the operational programmes of the various funds to the new context was very scarce, which limited the potential of this policy to offset the effects of the Great Recession of 2009 and the euro crisis on the poorest regions of the south (Madeira et al., Citation2021).

The problem of the insufficiency and, to some extent, inadequacy of cohesion policy has re-emerged with new contours, as we have recently experienced in Europe another recession of historic proportions, deeper than that of 2008–2009, due to the paralysis of several segments of activity because of the approach adopted to limit the effects of COVID-19 on public health. More recently, the upheaval associated with a war in Europe and the prospect of high inflation for a prolonged period have made this problem worse. This context is more demanding for EU regional policy.

In the context of the anaemic growth experienced in much of Europe in recent years, accompanied by major problems arising from stagnation or recession in many regions, the argument for a strong regional policy that produces convergence gains weight. Another argument which may be more controversial, but it is nonetheless increasingly relevant is the pursuit of justice. In the case of regional inequalities, it is mainly a matter of territorial/spatial justice, which is additional to the issues of social justice. The perception by populations that their regions are being unfairly neglected can lead to electoral revolts that feed populist and nationalist phenomena, which call into question the stability of the social and political system in which economies have been operating. It is also known that adherence to right-wing populist ideas in Europe seems to be based on growing economic difficulties, with loss of income and even of jobs, mainly in a certain type of region (Dijkstra et al., Citation2020; Ferrão, Citation2019), without the prospect of reversing the situation in the current context. Regional economic performance in recent years is associated with variations in regional affective polarisation, which in turn has implications for support for populist parties (Bettarelli & Van Haute, Citation2022).

Given the results of this research conducted in the EU and Brazil about the period of the 2008 crisis and its aftermath, and the current context of great socio-economic turbulence, a successful approach to the issue of regional inequalities would require strengthening direct regional policy, changing indirect regional policy, or combining the two in a different way. This could mean a strong place-based cohesion policy combined with non-territorial policies that function as indirect regional policy acting towards convergence.

The European place-based approach needs to overcome the limitations inherent in the logics of competitiveness and smart specialisation applied to all regions, which has prevailed since the beginning of the century. To this end, the place-sensitive approach in the aforementioned text by Iammarino et al. (Citation2019) can be a starting point, as it aims to distribute development more widely, providing for a specific set of policies for the less developed regions of the EU. However, the recent environment of high inflation and conflict in Europe will require bold approaches. Additionally, non-territorial policies that contribute to regional inequality need to be addressed.

In the case of Brazil, the main non-territorial policies that produced convergence are known and can be strengthened. The regional development policies of the past, based on attracting investment, yielded few results and the PNDR was not implemented. What has been lacking, therefore, is a regional development policy that delivers strong results. This can be achieved through a logic in line with that of the PNDR, inspired by elements of the EU’s cohesion policy, including the necessary budgetary support.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (184.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor Julián Mora-Aliseda, Universidad de Extremadura (Spain), for his support during the fieldwork in the region of Extremadura. We thank Professor Anieres Barbosa da Silva, Federal University of Paraíba (Brazil), for his support during the fieldwork in the state of Paraíba. We thank Professor Márcio Rogério Silveira, from the Federal University of Santa Catarina (Brazil), for his support during the fieldwork in the state of Santa Catarina. We thank the two anonymous reviewers for comments made on an earlier draft of this paper.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Almeida, A. N., & Azzoni, C. R. (2016). Custo de vida comparativo das regiões metropolitanas brasileiras: 1996–2014. Estudos Econômicos (São Paulo), 46(1), 253–276. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-416146128aaa

- Amparo, P. P. (2014). Os desafios a uma política nacional de desenvolvimento regional no Brasil. Interações (Campo Grande), 15(1), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1518-70122014000100016

- Ancien, D. (2005). Local and regional development policy in France: Of changing conditions and forms, and enduring state centrality. Space and Polity, 9(3), 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562570500509877

- Barzotto, M., Corradini, C., Fai, F., Labory, S., & Tomlinson, P. R. (2020). Smart specialisation, industry 4.0 and lagging regions: Some directions for policy. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1803124

- Bettarelli, L., & Van Haute, E. (2022). Regional inequalities as drivers of affective polarization. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 9(1), 549–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2022.2117077

- Bristow, G. (2009). Limits to regional competitiveness. In J. Tomaney (Ed.), The future of regional policy (pp. 25–32). The Smith Institute. http://www.smith-institute.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/TheFutureofRegionalPolicy.pdf.

- Carazza, L., & Silveira-Neto, R. M. (2022). Evaluating the regional expansion of Brazil’s federal system of vocational and technological education. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Regionais e Urbanos, 15(2), 212–246. https://doi.org/10.54766/rberu.v15i2.787

- Crescenzi, R., & Giua, M. (2016). The EU cohesion policy in context: Does a bottom-up approach work in all regions? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(11), 2340–2357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16658291

- Dąbrowski, M., Musiałkowska, I., & Polverari, L. (2018). EU-China and EU-Brazil policy transfer in regional policy. Regional Studies, 52(9), 1169–1180. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1431389

- De Grauwe, P. (2011). The governance of a fragile Eurozone. CEPS Working Documents, 346. Brussels: CEPS. http://www.ceps.eu/book/governancefragile-eurozone.

- Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2020). The geography of EU discontent. Regional Studies, 54(6), 737–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1654603

- European Commission. (2007). Growing regions, growing Europe: Fourth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Report. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion4/pdf/4cr_en.pdf.

- European Commission. (2016). Ex post evaluation of the ERDF and Cohesion Fund 2007-13. Commission Staff Working Document, SWD (2016) 318 final. Brussels: European Commission. http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/pdf/expost2013/wp1_swd_report_en.pdf.

- European Commission. (2017). My region, my Europe, our future: Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion. Report. Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/cohesion7/7cr.pdf.

- European Council. (2006). Council regulation (EC) No 1083/2006 of 11 July 2006 laying down general provisions on the European regional development fund, the European social fund and the cohesion fund and repealing regulation (EC) No 1260/1999. Official Journal of the European Union, 210(49). https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c155a0d3-3195-4e24-b499-a72f5dfc56ad/language-pt/format-PDF.

- Ezcurra, R., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Does economic globalization affect regional inequality? A cross-country analysis. World Development, 52, 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.07.002

- Farole, T., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2009). Cohesion policy in the European Union: Growth, geography, institutions. Working Paper for the Barca Report. London School of Economics, UK, January.

- Ferrão, J. (2019). Para uma geografia com todos os lugares: reflexões a partir do caso europeu. In A. Ferreira, J. Rua, & R. C. Mattos (Eds.), Produção do espaço – Emancipação social, o comum e a “verdadeira democracia” (pp. 55–72). Rio de Janeiro: Consequência Editora. https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/39708/1/ICS_JFerrao_Para_Uma.pdf

- Garretsen, H., McCann, P., Martin, R., & Tyler, P. (2013). The future of regional policy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 6(2), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst013

- Hadjimichalis, C. (2011). Uneven geographical development and socio-spatial justice and solidarity: European regions after the 2009 financial crisis. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18(3), 254–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411404873

- Hadjimichalis, C. (2018). Crisis spaces: Structures, struggles and solidarity in Southern Europe. Routledge.

- Iammarino, S., Rodriguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2019). Regional inequality in Europe: Evidence, theory and policy implications. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(2), 273–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby021

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2022). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Madeira, P. M. (2014). Dinâmicas Regionais Ganhadoras e Perdedoras na União Europeia Durante a Globalização Económica. Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, 37(3), 43–56. https://www.review-rper.com/index.php/rper/article/view/425 https://doi.org/10.59072/rper.vi37.425

- Madeira, P. M. (2019). Dinâmicas regionais e políticas de desenvolvimento territorial – Um olhar cruzado entre a UE e o Brasil (Doctoral dissertation). Institute of Geography and Spatial Planning of the University of Lisbon, Portugal. http://hdl.handle.net/10451/42268

- Madeira, P. M., & Vale, M. (2015). Desigualdade e espaço no capitalismo contemporâneo: uma questão de (in)justia territorial? Geosup-Espaço e Tempo (Online), 19(2), 196–211. http://www.revistas.usp.br/geousp/article/view/102771.

- Madeira, P. M., Vale, M., & Mora-Aliseda, J. (2021). Smart specialisation strategies and regional convergence: Spanish extremadura after a period of divergence. Economies, 9(4), 138. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9040138

- Marques, P., & Morgan, K. (2021). Innovation without regional development? The complex interplay of innovation, institutions, and development. Economic Geography, 97(5), 475–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2021.1972801

- Martin, R. (2001). EMU versus the regions? Regional convergence and divergence in Euroland. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(1), 51–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/1.1.51

- Martin, R. (2015). Rebalancing the spatial economy: The challenge for regional theory. Territory, Politics, Governance, 3(3), 235–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2015.1064825

- Martin, R., Tyler, P., Storper, M., Evenhuis, E., & Glasmeier, A. (2018). Globalisation at a critical conjuncture? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy002

- McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.799769

- Neto, A. M., Costa, M. A., Resende, G. M., Mendes, C. C., & Galindo, E. P. (2017). Desenvolvimento Territorial no Brasil: Reflexões sobre Políticas e Instrumentos no Período Recente e Propostas de Aperfeiçoamento. In A. M. Neto, C. N. Castro, & C. A. Brandão (Eds.), Desenvolvimento Regional no Brasil – Políticas, Estratégias e Perspetivas (pp. 37–64). IPEA. https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/index.php?option=com_content&id=29412.

- O’Brien, K. L., & Leichenko, R. M. (2003). Winners and losers in the context of global change. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(1), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.93107

- OECD. (2010). Regional development policies in OECD countries. OECD regional development studies. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087255-en.

- Parr, J. B. (2015). Neglected aspects of regional policy: A retrospective view. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 33(2), 376–392. https://doi.org/10.1068/c1371r

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Tomaney, J. (2007). What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies, 41(9), 1253–1269. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701543355

- Presidência da República do Brasil. (2007). Decreto N. 6.047, de 22 de fevereiro de 2007. http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2007/decreto/D6047.htm.

- Ramajo, J., Márquez, M., & De Miguel, F. (2014). Economic impact of the European funds in extremadura during the period 2007–13. Investigaciones Regionales, 29, 113–128. https://investigacionesregionales.org/en/article/impacto-economico-de-los-fondos-europeos-en-extremadura-en-el-periodo-2007-2013/.

- Reis, J. (2015). Território e políticas do Território. A interpretação e a ação. Finisterra, 50(100), 107–122. https://doi.org/10.18055/Finis7868

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2012). Trade and regional inequality. Economic Geography, 88(2), 109–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01147.x

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Rodrigues, J., & Reis, J. (2012). The asymmetries of European integration and the crisis of capitalism in Portugal. Competition & Change, 16(3), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1179/1024529412Z.00000000013

- Silveira-Neto, R. M., & Azzoni, C. R. (2011). Non-Spatial government policies and regional income inequality in Brazil. Regional Studies, 45(4), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400903241485

- Silveira-Neto, R. M., & Azzoni, C. R. (2012). Social policy as regional policy: Market and nonmarket factors determining regional inequality. Journal of Regional Science, 52(3), 433–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00747.x

- Soja, E. W. (2010). Seeking spatial justice. University of Minnesota Press.

- Thirlwall, A. P. (2000). European unity could flounder on regional neglect. The Guardian, 31 January, 23. http://www.theguardian.com/business/2000/jan/31/emu.theeuro.

- Tomaney, J., Pike, A., & Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2010). Local and regional development in times of crisis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 42(4), 771–779. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43101

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). (2014). Human development report 2014: Sustaining human progress: Reducing vulnerabilities and building resilience. United Nations.

- Vale, M. (2012). Conhecimento, Inovação e Território. Edições Colibri.

- Vale, M. (2014). Economic crisis and the Southern European regions: Towards alternative territorial development policies. In J. Salom & J. Farinós (Eds.), Identity and territorial character – Re-interpreting local spatial development (pp. 37–48). Universitat de València.

- Wigger, A. (2023). The New EU industrial policy and deepening structural asymmetries: Smart specialisation Not So smart. JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 61(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.13366