ABSTRACT

Entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) is a novel perspective to analyse the interplay between support systems and businesses in regions. Simultaneously, universities have been playing increasingly important roles in entrepreneurship, fostering economic growth both through the wider regional economy (RE) and their own university EEs (UEEs). Entrepreneurs in residence (EiRs), chosen by universities as exemplar entrepreneurs, therefore provide potentially important conduits between the regional economy, UEEs and entrepreneurs, leading us to explore how and why do EiRs and universities interact in relation to entrepreneurial ecosystems to enhance the regional economy? Our qualitative study of a UK university case, conducted in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic which severely impacted many businesses’ access to resources, gives a particular temporal context to this research. It identifies accessing resources, building legitimacy and undertaking bridging activities as the three highest-level dimensions characterising EiR–university interactions, which have relevance for both the UEE and regional economy more widely, offering a framework for future EiR programmes. This study contributes to the regional entrepreneurship and EE literature, by examining the role of regional universities as anchor tenants and catalysts of entrepreneurial growth and resilience within regions, and calls for further research into the evolution of EiR–university interactions in different institutional contexts.

1. INTRODUCTION

Entrepreneurial ecosystems (EEs) position the entrepreneur at the centre of regional economic development, emphasising the interplay between regional business support systems and the business itself (Cho et al., Citation2021). Simultaneously, academic discussion on how higher education institutions (HEIs) could foster regional economic growth and societal change has attracted attention in the regional development literature (Breznitz & Zhang, Citation2022; Rossi et al., Citation2023), with universities playing increasingly important roles in fostering entrepreneurship. Within the different types of universities, entrepreneurial activity is influenced by stakeholders, both internal and external resources, as well as physical and virtual new venture incubation (Radko et al., Citation2023). These activities support both the university EEs (UEEs) and wider regional economy (RE).

However, a holistic and systemic approach to understand how UEEs can best support early-stage entrepreneurs, and the RE more widely, remains under-theorised. Specifically, identifying the evolving elements of institutional resilience of entrepreneurial universities is critical to regional development during external shocks (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) when other entrepreneurial support becomes limited (Belitski et al., Citation2024). Entrepreneurs in residence (EiRs), chosen by universities as exemplar regional entrepreneurs, provide potentially important conduits between REs and UEEs, leading us to formulate the following research question: How and why do EiRs and universities (through the EiR programme) interact in relation to entrepreneurial ecosystems to enhance the regional economy?

To answer our research question, we designed a qualitative study to examine in-depth, the interactions between the entrepreneurs and the university-based entrepreneurship support programme at university A in the southeast of the UK. In particular, we conducted 20 qualitative interviews between 2022 and 2023 with EiRs as well as experts in the ecosystem, investigating their understanding of the relationship between the RE and UEE. Our research was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when businesses, especially SMEs, were reportedly severely impacted, with limited access to resources. This gave us an extreme context, and an opportunity to investigate their relationships with, and contribution to, REs.

We find that the EiR programme fulfils a bridging function between entrepreneurs and the university, that not only provides unique resources for both, but also spills over to the wider RE. While EiRs seem to have received limited support from other stakeholders in their regions during the COVID-19 pandemic, resources and support provided by the UEE are viewed as especially important for their business development. At the same time, the university also anchored the role of bridging between the entrepreneurs and REs. These bridging activities and related legitimisation processes that EiR programmes provide are found to be important and relevant for EiRs, UEEs and REs more widely. They allow EiRs to promote themselves to local communities, whilst simultaneously legitimising universities within the RE, thus allowing universities to play a greater role in supporting economic development and building regional resilience.

Our study therefore contributes to regional entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystem literature by building on the limited knowledge of how universities achieve their role in supporting economic and social development in specific regions. This paper extends current understanding in several ways. First, it tracks the horizontal evolution of entrepreneurial ecosystems by examining the role of the regional university as an anchor tenant and catalyst of entrepreneurial resilience within the regional economy. Second, it analyses how businesses utilise the UEE to create sustainable change within their business and connect to the regional economy (Pugh et al., Citation2021). Third, it indicates how UEEs can use EiRs to evolve, which is important since higher education institutions (HEIs) have gained recognition as drivers of technological advancement and regional economic development (Boschma, Citation2015). Finally, this study contributes to examining the multi-level engagement of EEs to better understand the interaction between the elements within the EE. Empirically, it enriches our understanding of the impact of COVID-19 on regional development.

The structure of the paper is as follows. The next section of the article focuses on theory development via the literature, Section 3 presents the research methodology and Section 4 addresses our findings. The final section presents a discussion and contributions.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. Entrepreneurial ecosystem

Entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) is defined as ‘a set of independent actors and factors coordinated to enable productive entrepreneurship’, making the regional context a vital consideration for entrepreneurial ecosystems (Stam, Citation2015, p. 1765). Entrepreneurship is critical for the innovative transformation of regional development, and the EE concept encapsulates the regional socio-economic community bounded by entrepreneurial activity and institutional settings (Khlystova et al., Citation2022). Though for real transformation to occur, place-based alignment of the elements is also critical, with EEs being developed at national systems level (Acs et al., Citation2014), or within regional communities (Sorenson, Citation2017). However, the interaction between ecosystem elements within the RE has rarely been explored, especially those with and within universities.

2.2. Entrepreneurial universities and entrepreneurs-in-residence (EiRs)

Universities face increasing pressure to address the challenges of the knowledge economy, while contributing to economic and social development, and mitigating decreasing funding from the government (Pickernell et al., Citation2019). They play an increasing role in incubating entrepreneurs within the region, enhancing the entrepreneurial intent of students, cooperating with industry via knowledge transfer, and supporting the commercialisation of scientific ideas (Etzkowitz et al., Citation2008). Some local universities tap further into enterprising universities (Woollard et al., Citation2007) or focus on third stream activities, depending on their research intensity (Hewitt-Dundas, Citation2012). In addition, by upgrading the technology base of the region, universities can enhance its capacity for the evolution of entrepreneurship.

Identifying relationships and interactions between entrepreneurs and the university is therefore important in understanding universities’ role in contributing to regional development. While the definition of ‘entrepreneurs in residence’ (EiRs) is not clearly defined in the literature and the terminology is often used interchangeably in different contexts. We propose a more detailed working definition of an entrepreneur in residence (EiR) as:

an individual entrepreneur who is initially external to the university, is potentially an important node in the external EE, has a formally agreed, recognised and publicised, relationship status with the university, and who interacts with the university in multiple ways which include activities such as engaging with students and graduate entrepreneurs/local economy.

Our review of the literature highlights several gaps. First, only a few studies have introduced the evolutionary aspect in the context of UEEs, and fully recognised the multiple potential roles universities have as one of the anchors of EE. Taking an evolutionary lens allows us to analyse the university’s evolving role within the RE. Second, mechanisms identifying university to EiRs (U-to-E) inter-relationships, and how they contribute to the growth of REs need further exploration in the literature. Third, the EiR concept is still fragmented in different contexts, requiring us to break down these relationships and better determine the processes at work, in order to explain how these businesses maintained their resilience during exogenous shocks via the UEE, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. RESEARCH METHODS

3.1. Research design

Our research is explorative by nature (Yin, Citation2009) and seeks to answer our research question through inductive theory-building using qualitative interview data (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). We follow a similar design to previous work on understanding EiRs, (e.g., study by Pugh et al., Citation2021 identifying learning mechanisms of EiR programmes), to gain insights into changes in the underlying mechanisms interacting between universities and EiRs.

3.2. Case context

We purposely selected the entrepreneurs from an EiR programme at a higher education institution A in the Southeast of the UK. With a unique focus on both practical and academic development, university A has a strong orientation towards innovative and entrepreneurial education making it a theoretically interesting case (Symon & Cassell, Citation2012). University A is located in a region where a wide range of entrepreneurs have growing ambitions in actively expanding their networks regionally and internationally, providing a good base for researching inter-relationships between EiRs and regional development. Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic provides another extreme context for our research where all three stakeholders, EiRs, UEE and RE are challenged. COVID-19 pandemic is found to severely impact business behaviour (Belitski et al., Citation2022), identity (e.g., Alguera Kleine et al., Citation2023), resource relocation, and resilience (Dörr et al., Citation2022).

3.3. Data collection

We conducted a two-stage data collection process. First, we formed a general understanding of the establishment of the EiR programme through conversations with relevant members of staff and via observations. This provided important contextual understanding for our later interpretation of the focused EiR and stakeholders interviews (see Appendix Tables A2 and A3 interview protocols in the online supplemental data). Second, we collected data from three sources to ensure a thorough understanding of the interviewees and to enable data triangulation (Yin, Citation2009), namely interviews with the EiRs and stakeholders, observations of EiRs’ participation in the university, as well as relevant websites to gain a deeper understanding of the EiRs’ business activities. We contacted EiRs registered in the university, identifying participants from various industries and including both males and females to ensure broader representation and analytical generalisability. We finalised data collection from voluntary respondents when we reached saturation, after 15 interviews with EiRs. To triangulate, we also purposefully selected and interviewed five key stakeholders in university A’s EiR programme. Overall, we held 20 semi-structured interviews, ranging from 30–60 min each. We anonymised the interviewees using letter names (see Appendix Table A1 interviewee profiles in the online supplemental data).

3.4. Data analysis

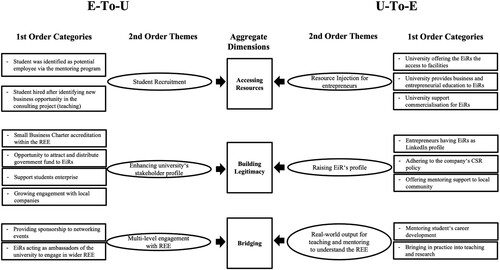

Data from interviews have been transcribed and carefully read to get an overview of the contents. We iterate between data and literature throughout the data analysis process (Corley & Gioia, Citation2011). The authors also identified the nuances of each transcript by both using textual and audio recordings to enhance their understanding of the phenomenon. In the first instance, transcripts were analysed using key and frequent concepts, terminologies, phrases or sentences and categorised and indexed into suitable codes using open coding (Corley & Gioia, Citation2011). We then re-read the transcripts to identify similarities and differences between each participant in the same group (i.e., the EiR’s or the university’s perspective). These within-case and across-case codes form our first-level concepts. We then proceeded to understand the links between the first order codes to form our understanding of the second-order themes. For example, the EiRs’ activities in networking and representing the university in engaging with the RE, forms the multi-level engagement with REs. Lastly, we compared the second-order themes between groups, and theorise the aggregate dimensions between the EiRs and university-level (see ).

4. RESULTS

Our findings identified several common themes and aggregate dimensions that highlight the bi-directional relationship between university and EiRs, that is, university to EiRs (U-to-E) interactions and EiRs to university (E-to-U) interactions, as well as the ‘bridging’ effects that also resulted in wider engagement with the RE (see ). These interactions shed light to the wider and dense exchanges within REs. We discuss the different themes identified under the three key dimensions, i.e., accessing resources, building legitimacy, and bridging in the following section. Through constant comparison between coding and literature we found that the first dimension (accessing resources) has been widely studied in EE literature (e.g., Harima et al., Citation2020). However, the two remaining dimensions (building legitimacy and bridging) were rarely examined empirically, and this formed the main theoretical contribution of our research. The key exemplary quotes identified are presented in Appendix Table A4 in the online supplemental data.

4.1. U-to-E interaction leading to wider contribution to RE

Three main themes were categorised under the U-to-E interactions. This included resource injection for entrepreneurs, raising EiR’s profiles, and real-world output for teaching and mentoring to understand the RE.

4.1.1. Resources injection for entrepreneurs

One of the main resources provided to EiRs by the university is access to facilities for either meetings or other events: ‘But what I really like is obviously access to facilities … we’re using the future technology centre. So, the next week we are hosting an event … that’s been amazing to us to impress clients and potentially raise funds’ (B). Interactions with students equally provided EiR’s with an opportunity to identify relevant talent for their organisations during mentorships and internships; thus contributing to employment growth within the RE. The university also provided relevant training to EiRs, including supporting entrepreneurs’ commercialisation efforts as one founder emphasised: ‘the programme (a university training programme for entrepreneurs) helped me to gain the managerial and entrepreneurial knowledge to commercialise our idea’ (C). The training also provided them with further scaling and funding opportunities within the RE.

4.2.2. Raising EiRs’ profile

Our findings also identified a number of other motives driving EiRs’ participation in the programme. This includes increased exposure with the media and local community as a result of their EiR status. Some of the EiRs were regarded as more favourable during the bid selection process. They were also able to ‘attract local government support and developed stronger partnerships with local businesses’ (D). The EiR was actively participating in teaching and mentoring activities within the university as an alumnus which led to wider engagement. However, EiRs also emphasise that while the increased status might be beneficial, their primary motive for engaging in the programme is because it allows them to support their local community through the sharing of experiences.

While EiRs’ view the programme as a means of giving back to their community, it also lends credence to their businesses and allows them to build trust within their community. Being able to highlight the university’s involvement in their events can thus be viewed as receiving a ‘stamp of approval’ (F) or legitimisation. It thus enables entrepreneurs to contribute to their firm’s corporate social responsibility (CSR) policies. For example, a local EiR volunteered for the programme to ‘create opportunities for business to thrive in the city’ (H).

4.1.3. Real-world input for teaching and mentoring

EiRs also show a high level of engagement with the RE via the activities undertaken with the university. Some of the activities they have been involved in include academic teaching, mentoring, pitching events, online sessions, and so on. These activities can also be viewed as bridging, linking theory and practice to offer ‘business perspective for the student’ (S), making an impact within the university and ‘were excited to see the meaningful collaborations’ (F) while also raising awareness and encouraging engagement within the broader RE.

4.2. E-to-U interaction widening UEE-RE interaction

Similarly, we identified three main themes that fall under the E-to-U interactions. This included student recruitment, Small Business Charter (SBC) Accreditation, and multi-level engagement with the RE.

4.2.1. Student recruitment

Engaging in the programme is one route through which EiRs (through interactions with students) are able to enhance the university’s value adding to student recruitment. This can be via their mentorship programme, or through internship opportunities, particularly beneficial for the students (and by extension to university programmes), who get opportunities to assist in providing solutions to real-life problems they might encounter, while gaining relevant experiences that increase their employability. Hence, the EiR programme has benefited the RE by building ‘mutual trust with the phenomenal talent’ (J) and hiring local talent.

4.2.2. Enhancing university’s stakeholder profile

One dimension to the Small Business Charter (SBC) is the requirement that universities demonstrate how they engage with SMEs and other key stakeholders in their region for growth. In the broad university context, SBC accreditation can therefore be viewed as a major motivation behind establishment of an EiR programme if one did not exist previously. The founding manager of the EiR programme mentioned the importance of the accreditation process and the motivation to commence the programme: ‘We had a small business charter accreditation, one in 2015, … from 2016, and how we could make it work with the EiR programme’ (M). Having an EiR programme can be seen as supporting SBC status, improving the likelihood that universities are ‘accredited’ within the broader RE, through a very explicit enhancement of their stakeholder diversity via explicit SBC accreditation and EiR programme activity. Similarly, the SBC also explicitly ensures that universities provide support to local student enterprises. This is normally fulfilled through various programmes run by the university targeted at potential student entrepreneurs and actively involving EiRs.

4.2.3. Multi-level engagement

Participation in the programme, also helps create greater awareness with other universities and businesses within the RE and is viewed as an important point of contact. EiRs perceive themselves as ‘ambassadors of the university’ (H) to ‘represent the university and promote their activity to local governments and chambers of commerce’ (K). as they engage with businesses in the wider RE, with some even providing sponsorship for local events organised by the university. In the long-term, such exchanges could also potentially facilitate greater engagement and interactions between EiRs, universities, and REs.

5. DISCUSSION

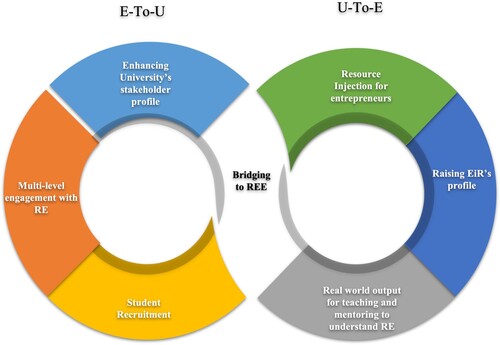

Our results provide a better understanding of how universities, and specifically EiR programmes, facilitate dynamic interactions between entrepreneurs and the UE that subsequently enable greater engagement and contribution to the RE (Breznitz & Zhang, Citation2022). We identify three key dimensions of these interactions, namely (1) accessing resources, (2) legitimacy building and (3) bridging, with spillover effects on the RE. The framework is illustrated in below.

Figure 2. Nested interaction between the university and EiRs.

5.1. Accessing resources enables nested interaction between the university and RE

Increased interaction between EiRs and the university that is facilitated by the EiR programme enables access to resources related to research, training, mentorship, knowledge transfer and academic spinoffs. The impact of these interactions is also felt within the broader RE due to increased engagement and injection of resources, by both the university and EiRs, into the local communities (Harima et al., Citation2020). Additionally, the specific role of universities in facilitating regional resilience (Boschma, Citation2015) is shown through its role in supporting EiRs during the COVID-19 pandemic, when EiRs experienced unexpected financial difficulties and disruption in the market and sought access to external resources. The EiR programme facilitated entrepreneur stability and long-term commitment to work within higher education, ensuring long-term collaborations with greater impact in shaping a specific socio-economic context (Porras-Paez, Citation2023).

5.2. Legitimacy building

While legitimacy building has been previously discussed within the university entrepreneurship literature, with universities obtaining access to grants via technology commercialisation and entrepreneurial education (Benneworth et al., Citation2017), our results highlight the role of EiR programmes in the legitimisation process. Establishing an EiR programme conveys accreditation on the university in (1) supporting small businesses, (2) enhancing student entrepreneurship and (3) engaging in the local community; thus explicitly signalling its connection with the local community and facilitating its role as a key player in driving socio-economic development in the region.

Similarly, the recognition and legitimacy gained by EiRs through joining the EiR programme, enables them to raise their profile with the local business community (Pugh et al., Citation2021). This leads to greater engagement with and contributions to the local community, for example through mentorship opportunities. Moreover, EiRs also benefit from developing wider networks (e.g., Small Business Charter or the local Chamber of Commerce) and connections to national and international entrepreneur communities, which facilitate knowledge exchange across multiple-levels and geographic boundaries (Breznitz & Zhang, Citation2022). Furthermore, as the COVID-19 pandemic, necessitated the reorganisation of business models, EiR programmes facilitated EiRs’ legitimisation of their alternative business models by connecting them with the UE and wider RE.

5.3. Bridging to RE

The bridging activities undertaken by universities highlight their role in evolving the local ecosystem. Our cases show how universities can provide a platform for EiRs to promote their presence, fostering entrepreneurship within the region (Creutzberg et al., Citation2024). This was especially relevant during times of crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, when typical RE support functions were disrupted either through weaker ties between elements or temporary cessation of support. Even though EiRs typically connected to wider cross-locational EEs rather than relied on RE support systems, the COVID-19 pandemic acted as a trigger for greater engagement with UEEs. These were subsequently viewed as important for the survival of their businesses, with the university also anchoring the role of bridging between EiRs and RE.

Additionally, even though EiRs’ businesses were located within a specific region, their clients were often based in other regions or UK-wide, resulting in greater involvement with broader ecosystems than the local RE. The national involvement of EiRs enabled them to contribute to bridging activities by promoting the UEE community to wider regions – the EiRs acting as ‘ambassadors’ of the university. Consequently, we argue that EiRs develop and build university-entrepreneur interactions to maintain and enhance their resilience within REs and universities in a number of ways, whilst universities use EiR programmes to develop and build university-entrepreneur interactions that support their activities in the RE. Interestingly, we found that the COVID-19 pandemic played a key role, not only in attracting entrepreneurs to the EiR programme, but also in expanding the role of the university in contributing to building resilience within the wider RE.

6. CONCLUSIONS

6.1. Contributions

Our study therefore contributes to regional entrepreneurship and EE literature by building on the limited knowledge of how universities achieve their role in supporting economic and social development in specific regions (Radko et al., Citation2023). By adopting an evolutionary lens in understanding the context of UEEs, and specifically focusing on EiRs, our study draws attention to the dynamic interactions between different ecosystem elements and emphasises the role of universities in building regional resilience (Breznitz & Zhang, Citation2022).

First, it sheds light on the horizontal evolution of EEs by highlighting the role of the regional university as anchor tenant and catalyst of entrepreneurial growth and regional resilience. The multiple, dynamic and reciprocal interactions between EiRs and the university (through its EiR programme) results in resource and knowledge spillover to the wider community, thus contributing to regional resilience in times of exogenous shocks such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Second, it shows how businesses utilise the UEE to create sustainable change within their organisation and connect to the regional economy (Pugh et al., Citation2021). The legitimisation process that is facilitated through the EiR programme, provides opportunities for EiRs’ greater engagement with, and contribution to, local communities. Simultaneously, EiR’s legitimise universities within the RE, enabling universities to have a more prominent role in shaping and supporting socio-economic development within the region.

Third, it draws attention to how UEEs can use EiR programmes to evolve, by emphasising the bridging activities between universities and EiRs and its relevance to the RE. Bridging activities facilitate increased multi-level engagement between the UEE and the RE, and establishes universities as key players in driving technological advancement and regional economic development (Boschma, Citation2015).

6.2. Limitations and future research directions

This study, however, has some limitations. First, it is based on the in-depth investigation of a single HEI during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our theorisation of the ecosystem offers unique insights and extensions to the regional entrepreneurship literature, we recommend further studies of different contexts to examine our theorisation and its generalisability. For example, future research could look at the impact of teaching and research outcomes of EiRs in universities, particularly in areas such as: (1) treating teaching activities as bridging activities both between the EiRs and the university and (2) investigating the impact on the entrepreneurship-ready graduates these teaching activities should produce.

Second, while our study is based in the UK context, in order to fully unpack the EiR–university interactions and build its boundary conditions, it is necessary to expand our theorisation to multiple national environments. Thus, further research in different institutional contexts (i.e., at national or ecosystem-level), especially considering variations in EiR activities and the terminology referring to EiRs would be useful.

Consequently, the following four propositions for future research can be developed from these results:

P1: Entrepreneurs-in-residence (EiRs) develop and build university-entrepreneur interaction to maintain and enhance their resilience within REs and UEEs in a number of ways.

P2: Universities use entrepreneurs-in-residence (EiRs) programmes to develop and build university-entrepreneur interaction to support their activities in the RE.

P3: EiRs and universities use a range of activities to bridge to the RE.

P4: The COVID-19 pandemic has played a key role in the attraction of entrepreneurs to the EiR programme, the expansion of UEEs and the role of the university in the wider RE.

6.3. Practical implications

Empirically, our research shows that under constrained situations, like the COVID-19 pandemic, EiR programmes become an important bridge between EiRs, UEEs and REs. Our findings have implications for universities, policymakers and governments seeking to develop entrepreneurial ecosystems in their regions. In particular, there is need for more clearly articulated aims of EiR programmes, with resources being allocated accordingly in order to achieve the desired results, and to more effectively link EiRs, universities and REs. We, therefore, propose a broad definition of an EiR programme as:

explicitly including, both for universities and entrepreneurs, access to valuable resources, opportunities that build both internal (UEE) and external (RE) legitimacy, and activities that build bridges with the RE.

ETHICS

We confirm that informed consent was provided by the research subjects (or their parents/ guardians). We also obtained formal ethics approval from the University of Portsmouth (reference number: BAL/2022/28/CHO). The consent was given via electronic document (a written informed consent) and covered the following: (1) project title, (2) aim of the project, (3) scope of the data collection, (4) confirmation of the consent form, (5) methods of data collection and how the data will be processed, (6) risks of participation and (7) contacts of the authors and data information officer (University of Portsmouth). All information was processed according to GDPR and the standards of University of Portsmouth, also identifiable personal data (i.e., names, company, region, etc) have been anonymised. We acquired the signed consent form from all participants.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (168.3 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to our editor Dr Danny Soetanto, the two anonymous reviewers, and Professor David Pickernell, for their helpful comments and guidance. We are also thankful for the funding received from the University of Portsmouth, Bal Research Project fund, supporting this research.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

There is no data to share.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Acs, Z. J., Autio, E., & Szerb, L. (2014). National systems of entrepreneurship: Measurement issues and policy implications. Research Policy, 43(3), 476–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.08.016

- Alguera Kleine, R., Ge, B., & De Massis, A. (2023). Look in to look out: Strategy and family business identity during COVID-19. Small Business Economics, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-023-00846-3

- Belitski, M., Cherkas, N., & Khlystova, O. (2024). Entrepreneurial ecosystems in conflict regions: Evidence from Ukraine. The Annals of Regional Science, 72(2), 355–376. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-022-01203-0

- Belitski, M., Guenther, C., Kritikos, A. S., & Thurik, R. (2022). Economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on entrepreneurship and small businesses. Small Business Economics, 58, 593–609. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00544-y

- Benneworth, P., Pinheiro, R., & Karlsen, J. (2017). Strategic agency and institutional change: Investigating the role of universities in regional innovation systems (RISs). Regional Studies, 51(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1215599

- Boschma, R. (2015). Towards an evolutionary perspective on regional resilience. Regional Studies, 49(5), 733–751. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.959481

- Breznitz, S. M., & Zhang, Q. (2022). Entrepreneurship education and firm creation. Regional Studies, 56(6), 940–955. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1878127

- Cho, D. S., Ryan, P., & Buciuni, G. (2021). Evolutionary entrepreneurial ecosystems: A research pathway. Small Business Economics, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00487-4

- Corley, K., & Gioia, D. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

- Creutzberg, T., Ornston, D., & Wolfe, D. A. (2024). Sector connectors, specialists and scrappers: How cities use civic capital to compete in high-technology markets. Urban Studies, 61(3), 549–566. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980231186234

- Dörr, J. O., Licht, G., & Murmann, S. (2022). Small firms and the COVID-19 insolvency gap. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 887–917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00514-4

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Engel, J. S., & Del-Palacio, I. (2011). Global clusters of innovation: The case of Israel and silicon valley. California Management Review, 53(2), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2011.53.2.27

- Etzkowitz, H., Ranga, M., Benner, M., Guaranys, L., Maculan, A. M., & Kneller, R. (2008). Pathways to the entrepreneurial university: Towards a global convergence. Science and Public Policy, 35(9), 681–695. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234208X389701

- Gordon, I., Hamilton, E., & Jack, S. (2012). A study of a university-led entrepreneurship education programme for small business owner/managers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(9-10), 767–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.566377

- Harima, A., Harima, J., & Freiling, J. (2020). The injection of resources by transnational entrepreneurs: Towards a model of the early evolution of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2020.1734265

- Hewitt-Dundas, N. (2012). Research intensity and knowledge transfer activity in UK universities. Research Policy, 41(2), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.10.010

- Khlystova, O., Kalyuzhnova, Y., & Belitski, M. (2022). Towards the regional aspects of institutional trust and entrepreneurial ecosystems. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-02-2022-0108

- Pickernell, D., Ishizaka, A., Huang, S., & Senyard, J. (2019). Entrepreneurial university strategies in the UK context: Towards a research agenda. Management Decision, 57(12), 3426–3446. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2018-1162

- Porras-Paez, A. (2023). Take it easy: How informal institutions shape an emerging economy entrepreneurial ecosystem. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 10(1), 581–591. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2023.2206887

- Pugh, R., Soetanto, D., Jack, S. L., & Hamilton, E. (2021). Developing local entrepreneurial ecosystems through integrated learning initiatives: The Lancaster case. Small Business Economics, 56(2), 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00271-5

- Radko, N., Belitski, M., & Kalyuzhnova, Y. (2023). Conceptualising the entrepreneurial university: The stakeholder approach. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 48(3), 955–1044. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-022-09926-0

- Rossi, F., Baines, N., & Smith, H. L. (2023). Which regional conditions facilitate university spinouts retention and attraction? Regional Studies, 57(6), 1096–1112. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1959909

- Sorenson, O. (2017). Regional ecologies of entrepreneurship. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(5), 959–974. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx031

- Stam, E. (2015). Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. European Planning Studies, 23(9), 1759–1769. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2015.1061484

- Symon, G., & Cassell, C. (2012). Qualitative organizational research: Core methods and current challenges. Sage.

- Woollard, D., Zhang, M., & Jones, O. (2007). Academic enterprise and regional economic growth: Towards an enterprising university. Industry and Higher Education, 21(6), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000007783099836

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed). Library of Congress Cataloguing-in Publication Data.