Abstract

Africa’s Legends is a mobile application developed by the Ghanaian game development company Leti Arts in 2012. The app consists of one game and two comics about eight ‘African’ superheroes. This article aims to give insight into the intersection of digital technologies and social class; it contributes to theorizing digital technologies as a means to express middle-class aesthetics, aspirations and senses of being in the world. It does so by showing how Africa’s Legends’ production process, particularly its aesthetics, is informed by historically embedded ideas about cultural heritage and notions about design and style. We trace how the upper middle-class background of the producers informs the production, distribution and reception of the app. According to the producers, digital technologies like Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator allow Africa’s Legends to be of the appropriate quality necessary to create a ‘new African’ style and to reach a global audience. However, Ghanaians of a less privileged background do not share this interpretation, which suggests that digital technologies mediate specific class aesthetics and aspirations.

Africa’s Legends est une application mobile développée en 2012 par la société de développement de jeux ghanéenne Leti Arts. L’application consiste en un jeu et deux bandes dessinées sur huit super-héros ‘Africains’. L’objectif de cet article est de présenter un aperçu du croisement des technologies numériques et de la classe sociale ; il contribue à théoriser les technologies numériques comme moyen d’expression de l’esthétique, des aspirations, et des impressions d’être dans le monde de la classe moyenne. Ceci en montrant comment le processus de production d’Africa’s Legends’, en particulier son esthétique, est informé par des idées inscrites historiquement dans l’héritage culturel et des notions sur la conception et le style. Nous retraçons comment l’appartenance à la classe moyenne supérieure des producteurs informe la production, la distribution et la réception de l’app. Selon les producteurs, les technologies numériques telles qu’Adobe Photoshop et Adobe Illustrator permettent à Africa’s Legends d’être de la qualité voulue et appropriée pour créer un ‘nouveau style africain’ et de toucher un public international. Cependant, les Ghanéens appartenant à un milieu moins privilégié ne partagent pas cette interprétation, qui suggère que les technologies numériques médient une esthétique et des aspirations spécifiques à une classe.

Introduction

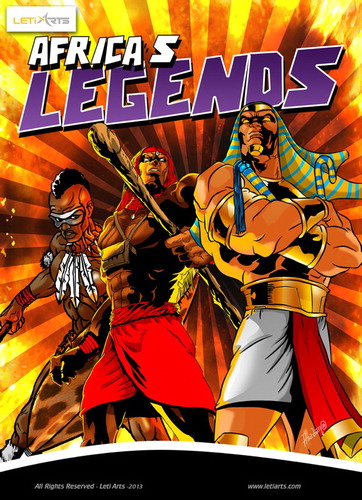

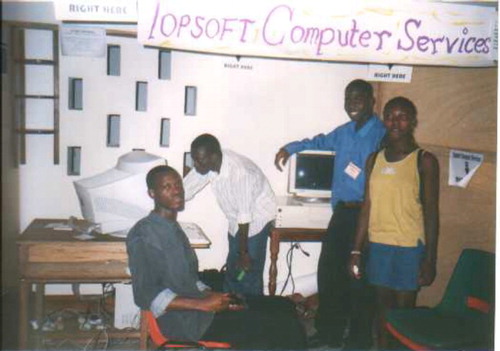

In 2012 the Ghanaian game development company Leti Arts launched a mobile application called Africa’s Legends (Leti Arts Citation2016). This app includes one game and two comics about eight ‘African’ superheroes called Ananse, Bobo, Pharaoh, Shaka, Shizo, Sundi, Ruddy and Wuzu who, together, form Africa’s Legends. When opening the app, the player is immediately confronted with several of the heroes, displayed on the digital covers of the comics. On the first cover Ananse is portrayed as if he is looking directly at the player with great glooming yellow eyes. He has grey curly hair, brown skin, wears a mask, a red belt, and a tight green suit with a yellow spider on his breast that accentuates his muscles. On the second cover two other heroes, Wuzu and Pharaoh, are framed as if the player is looking up to them. Wuzu is holding a staff and Pharaoh has his arms crossed in front of his chest, holding a sceptre and staff. Both are very broad and muscular and are staring into the distance, suggesting that they are ready to face whatever is coming to them. Pharaoh has light brown skin and wears a lot of gold: he has golden knee-high boots, a golden belt, golden arm – and wristbands, a long golden, pointy beard, and a blue and gold striped headdress, sceptre and staff. Wuzu has red hair, brown skin, and wears a red necklace, red skirt and red wristbands. All the heroes are drawn using simple, thin but strong lines, bright colours and shading that accentuates their muscles. On the one hand, the heroes appear to be inspired by African history and folklore: the red costume of Wuzu reminds us of the Maasai warriors in Kenya and Tanzania; the beard, headdress, staff and sceptre of Pharaoh are clear references to popular imaginaries of the famous rulers of Ancient Egypt; and the spider on Ananse’s suit is a symbolic nod to Kwaku Ananse, the Ghanaian god turned trickster spider. On the other hand, the heroes are reminiscent of the superheroes of DC and Marvel Comics. They have, for instance, heroic poses and prominent muscles. There are also similarities in drawing style, as can be seen in and . For example, the contours of superheroes are drawn using thin, clean and strong lines, which are filled with bright colours.

In 2013, Innovation Ghana – an initiative of the Ghanaian Ministry of Trade and Industry and Google – conducted a series of interviews with Ghanaian technology entrepreneurs ‘to celebrate […] home-grown innovators and [to] discuss what is needed to bring Ghana to the fore of innovation and entrepreneurship’. One of the interviewees, the CEO of Leti Arts, Eyram Tawia, explained what motivated him and his team to create Africa’s Legends:

Africa has so much history to tell from our views. […] We want to tell these stories in interactive ways, so they [the superheroes] will grow as big as Batman, as big as Superman, for even Superman to invite Ananse to feature in a DC movie episode. We at Leti Arts make games from Africa, not for Africa. […] We want to serve Africans and the world. (Innovation Ghana Citation2013).

The idea of Leti Arts to create African superheroes is part of broader trends on the African continent. As described in the recent special issue of the Journal of African Cultural Studies about the so-called Afro-superheroes, not only in Ghana, but also in countries like Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria and South Africa, comic book artists and performance artists are creating African superheroes to position themselves in society and the contemporary sociocultural arena (Coetzee Citation2016, 241–243). Some of these artists, like Leti Arts, have been influenced by DC and Marvel Comics (Omanga Citation2016). Indeed, Leti Arts is part of a network of several African game development companies run by young middle-class professionals that use African history and folklore to create fantastical superheroes. For instance, in Nigeria a group of game developers is creating Throne of Gods. According to their Facebook page, this is ‘an epic fighting game based on African mythology’ (ThroneOfGodsDevs Citation2016). Recently, the Cameroon-based Kiro’o Games published what they described as an African Fantasy action role playing game called Aurion: Legacy of the Kori-Odan (Kiro’o Games Citation2015). In Ghana, a handful of individuals and smaller companies have developed games, such as the mobile game Ananse Rises developed by Kente Games, the studio of Wahib Fahrat (Kente Games Citation2016). It is fascinating how African heritage features prominently in comics and games.

Since the early 2000s, African history and culture have increasingly been figuring in popular culture and various media across the continent and in the diaspora. Particularly, African heritage is being refashioned into styles and brands that are circulating amongst young middle-class Africans (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2009; De Witte and Meyer Citation2012, 52, 60; Shipley Citation2013). De Witte and Meyer argue that these new mediatized forms of heritage fit well into the identities and globalized consumer lifestyles of younger generations (Citation2012, 60). According to Shipley (Citation2013) digital technologies and digital media contribute to the popularity and circulation of these products as they facilitate production and distribution, allowing for their consumption and appropriation in various contexts. Beside the refashioning and circulation of popular forms of African history and culture, we would like to pay attention to their production and how that mediates particular aspirations and aesthetics. A crucial element of an app like Africa’s Legends is that the digital technologies and coding skills involved in its production could only be acquired and produced by a particular section of the Ghanaian population. This group was the first generation to grow up with access to digital technologies and a wide variety of digital media in the 1980s and 1990s. The Leti Arts team considered the use of programs like Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop necessary for the production of what they labelled ‘quality’. According to them, a more outstanding quality of the design was not only necessary for the global distribution of the app, but also for the creation of a ‘new African’ style. With this style the producers meant to position themselves as frontrunners of self-confident global citizens in Ghanaian society and in Africa in general; in Tawia’s own words: ‘to change Africa into a new Africa’. In this article, we show how certain digital technologies play an important role in this self-understanding and self-presentation. In other words, digital technologies mediate aesthetic preferences, aspirations and senses of being in the world and the close study of the production of Africa’s Legends thus gives insight into the way digital technologies articulate social dispositions. We focus on the crucial role of style and aspiration in this process.

In the following sections, we first we examine the family background of the producers growing up in the 1980s and 1990s, in which they had access to education, television, digital media and software, and were raised with specific ideas about success. Then we trace how the producers used digital technologies like Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator to create the aesthetic ‘quality’ they deemed necessary for the ‘new African’ style of the superheroes. We analyse how this production process was both influenced by the presence of certain TV programs and access to technologies, as well as a means to express their position as young, confident and ambitious Africans in both Ghana and the world. We end by exploring how the app was received by Ghanaians from similar yet less privileged backgrounds. While the app resonates with fellow upper middle-class Ghanaians, for others the aesthetics of the app were ‘too un-African’ or of ‘too low quality’ to be globally competitive. In contrast, at the same time, the app is celebrated in the global tech scene for its Africanness. This contradiction is insightful to understand the social position of the game developers in Ghana and to tease out the intersection of digital technologies and social class.

Technologies, style and social class

In recent years, many scholars have zoomed in on the role of technologies and the importance of style in the production and circulation of media in Africa (Larkin Citation2008; De Witte and Meyer Citation2012; Shipley Citation2013). According to Larkin (Citation2008), we need to be cautious about the all-too-familiar narratives of technological ‘revolution’ and ‘development’, as media technologies do not always work in the way that they are intended to do. While technologies are developed and styled with certain goals in mind, their design provides them with a certain autonomous power; it allows them to be (re)appropriated and to have technological and social potential outside of the designer’s control. In other words, the way technologies affect social life is not one-dimensional but differs over time and in relation to cultural debates and social reconfigurations. Technologies can thus have different meanings to different people over time, and facilitate the manifestation of one’s social position in society.

Ferguson (Citation1999) has proposed to take up style as a way to analyse how people understand and position themselves. He coins the term ‘cultural style’ as performative practice, a cultivated competence that involves both deliberate self-making based on personal motivations, desires and aesthetic preferences on the one hand, and stimulated by structural social processes on the other. Instead of seeing style as a ‘secondary manifestation or prior identity which style then expresses’, Ferguson uses style as a ‘signifying practice’, that marks social significant positions and allegiances. ‘[I]t is not simply a matter of choosing a style to fit the occasion, for the ability of such choices depends on internalized capabilities of performative competence and ease that must be achieved, not adopted’ (Ferguson Citation1999, 96). Style, then, signals both achievement and ongoing aspiration and is thus central in self-perceptions. In a similar vein, De Witte and Meyer (Citation2012) have argued that African heritage is constantly restyled and remediated in the present, based on contemporary social circumstances, so as to articulate Africanness in various contexts.

Thinking about technology and style in this way provides a frame to study the intersection of social class, aesthetics and aspirations. It is outside the scope of this article to delve into the debate about the ‘rising middle class’ in Africa and the problems of the concept (Melber Citation2013; Lentz Citation2015). We use the term middle class not so much as a category that can be found out there in society but as signifying practice (Spronk Citation2014). Besides bringing into perspective how certain ‘conditions of possibility’ (Liechty Citation2012), such as access to education, networks and resources, facilitate social mobility and distinction, it is also important to look at people’s aspirations to climb the social ladder and to gain prestige. We thus approach the notion of middle class as an aspirational category (Heiman, Freeman, and Liechty Citation2012) rather than a fixed category, which means that we analyse the conditions of possibility that enable the pursuit of mobility and the (desire for) concomitant middle-class dispositions. The question then is how the material and symbolic dimensions of being middle class are dialectically intertwined in the production of class subjectivities and relations. According to Shipley, digital technologies are easily accessible to the African middle classes and what he calls a ‘culture of mobility’ reinforces the production, distribution and appropriation of digitally produced media to different contexts. As such, digital technologies qualify styles that reflect a sense of being in the world; through constant (re)appropriation and (re)styling, digitally produced media can come to express a means of being African in a globalized world. However, in the case of Africa’s Legends, the circulation provided by digital technologies is not as evident as proposed by Shipley; the app is appreciated in various ways by different groups in Ghana. This suggests that the relationship between the middle classes, style and digital technologies needs further exploration.

We argue that not only conditions of possibility, but also digital technologies and style both shape and are a means to express middle-class aspirations. The developers of Africa’s Legends grew up with specific access to education, digital technologies and media, and were encouraged by their parents to do well. Technologies were thus not only historically embedded (Larkin Citation2008), but connected to historical class circumstances (Liechty Citation2012). The preference for using Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator is informed by this historical context, just as the developers’ appreciation of ‘quality’ and ‘new African’ aesthetics. The creation of what the developers labelled ‘quality’ and the resulting style reveals their particular position in society. Furthermore, rather than their appropriation of African heritage circulating easily, it is met with apprehension by other Ghanaians while being applauded by the global tech industry in Accra.

Growing up with new technologies and digital media

Leti Arts was established by Tawia and the Kenyan Wesley Kirinya in Accra in 2009. In 2010, Kirinya established a Leti Arts office in Kenya’s capital city Nairobi. Depending on the amount of work available, the team in Accra consisted of 5–10 members; a fluctuating number of interns and freelancers, and three core members. These were Tawia, his childhood friend Nana Kwabena Owusu, responsible for marketing and communication, and ‘Eugene’ Kwame Akoto, the leading artist. Since Africa’s Legends has mostly been the idea of and developed by Tawia and his team in Accra, this article focuses solely on the office in Accra and the middle classes in Ghana. The article is based on fieldwork of five months in 2014 where the first author worked as an intern at Leti Arts, participating and studying the production, distribution and reception of Africa’s Legends. In this period, she assisted with the everyday creation of Africa’s Legends, contributed to the marketing of the app, participated in the conversations and discussions in the office, and conducted game elicitation with some of the target audiences in Ghana.

Furthermore, the author conducted life history interviews with 10 technology entrepreneurs and four of their parents and participated in their daily lives in the subculture that was called the ‘tech space’, ‘Afritech space’ or ‘tech start-up scene’ in Accra. We use the notion ‘tech space’ to refer to the interconnections and relationships making up a community of tech entrepreneurs, transnational NGOs, transnational corporations, and to a lesser extent the Ghanaian government in Accra, which was focused on the development of tech companies and the stimulation of tech entrepreneurship. Within this community, Tawia and Owusu were part of a group of mainly young upper middle-class Ghanaians who were the first to become tech entrepreneurs in the 2000s and owned technology start-ups, or worked for one. The interviewed technology entrepreneurs were all members of this group, close friends of Tawia and Owusu who often visited or worked from the office. They all grew up with similar access to technology and media, resulting in comparable career paths. They thus formed a group sharing similar dreams and concerns.

Tawia, Owusu and their tech entrepreneur friends’ experiences with technology and media should be placed in the context of the radical socio-political transformations in Ghana in the 1980s and 1990s. In the 1980s Ghana was governed by a military regime led by J.J. Rawlings and the economy and media were controlled by the state. Inspired by the policies of Ghana’s first president Kwame Nkrumah, J.J. Rawlings promoted a cultural heritage policy called ‘Sankofaism’. This policy aimed to reclaim those elements from the past which were considered relevant for the present day and framed cultural heritage as a precondition for the development, self-definition and legitimacy of the Ghanaian nation-state. It transformed the traditional festivals, heritage sites, dances and plays of different ethnic groups into one national cultural heritage style. Focusing on aesthetics and performance was a strategy to unify Ghanaians within the nation (Coe Citation2006, 57–60). In the mid-1990s, Ghana transitioned to a democracy and a liberalized economy. The state-controlled public sphere changed into a liberalized commercial space with many private media channels, which broadcasted different visions of culture, identity and belonging than portrayed by Sankofaism (De Witte and Meyer Citation2012, 46–48). Moreover, the opening up of the market attracted transnational telecommunication companies like MTN and Vodafone and led to an increase in the number of Ghanaians who could afford access to mobile telephones and the internet (Osiakwan, Foster, and Santiago Citation2007, 17, 18).

The parents of the tech entrepreneurs had achieved their middle-class status in the 1960s and 1970s. They were social climbers who benefitted from the education and job opportunities provided by the newly independent Ghanaian nation-state (Behrends and Lentz Citation2012). Often they had completed their PhDs in the United States or the United Kingdom and held high status jobs in government or transnational corporations, which gave them the opportunity to travel and/or spend extensive periods of time outside of Ghana and to build transnational networks of acquaintances. The parents of the tech entrepreneurs in this study were university lecturers and professors, or taught at the primary and junior high schools located on campus. Through their parents, the children learned from a young age that success was interwoven with access to transnational opportunities and networks. Their parents maintained high ambitions for the children; they encouraged their children to work hard in school and provided them with the means to fulfil their aspirations.

Because of their living conditions, the parents could provide their children with access to technologies and media that the majority of Ghanaians could not afford. For instance, Tawia, Owusu and other children with parents working at a university had access to a children’s library on campus, which included books for African children developed by foreign publishers. In the 1980s and 1990s, they were also some of the first who were able to buy televisions and computers, which were signs of modernity and prestige (Heath Citation1997, 270, 271). The tech entrepreneurs grew up watching television series broadcasted by the state-owned GBC TV, such as By The Fireside. This program was aired in the 1980s and early 1990s and the brainchild of the First Lady, Ms. Rawlings. Bringing into practice the idea professed by Sankofa ideology that one should reclaim from the past what had significance for the present day, the program tried to adapt the Anansenem to the medium of television to address contemporary issues like adolescent delinquency and how to fit in to society. The Anansenem are a collection of century-old folktales about Kwaku Ananse, a god that was cast down from heaven and turned into a cunning, trickster spider that could take human form. They were traditionally told by the fireside, or represented as such. In By the Fireside these stories were enacted by schoolchildren in a studio. For the tech entrepreneurs, this program came to represent how their generation learned about what it meant to be African; gathered around the television, instead of around the fireside (Heath Citation1997, 271–273).

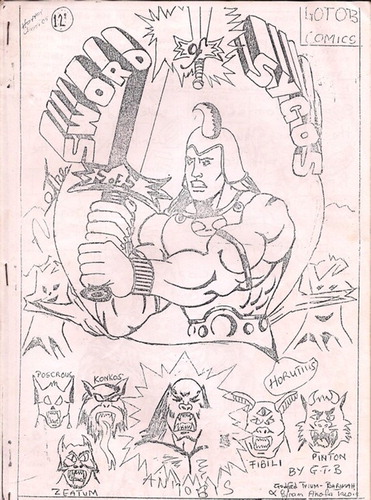

Television also gave the tech entrepreneurs access to different adventure and superhero series, especially after Ghana’s media liberalization. In the 1990s, they watched Journey to the West, a Chinese adventure series set in mythical times, and Captain Planet, an American animated series about a superhero, both broadcasted by GTV (former state broadcasting station GBC TV). Moreover, the tech entrepreneurs got access to adventure, superhero and fighting movies, series and games via their parents. On their international travels, they bought their children gaming consoles, fighting games like Streetfighter, and DC and Marvel comic books. In the case of Tawia, Owusu and their friends, the latter made such an impression that they started to draw their own superhero comics – such as Sword of Sygos, a comic inspired by Greek mythology ().

Figure 3. Sword of Sygos, developed in 1996/1997 when Eyram Tawia was in Junior High School © Eyram Tawia. 2016. Uncompromising Passion.

During their childhood, television also gave the children access to the state’s visions on technology, for instance through the children’s science quiz Kyekyekule, broadcast on Ghanaian state television. This program promoted the idea that technology should be used by Ghanaians to address local problems and to develop children into confident, self-reliant and ‘modern’ citizens (Heath Citation1997, 273, 274). Importantly, the parents of the tech entrepreneurs provided their children the conditions necessary to act upon these ideas. They allowed their children to develop their IT skills. For instance, they let them experiment with the home computer, enrolled them in extracurricular IT training courses, or bought programming books and computer parts during their international travels. They also allowed their children to start their own technology companies. For instance, Tawia and his friends started TOPSOFT at the end of Junior High School and developed software for a local radio station – thus bringing the use of digital technologies as promoted by Kyekyekule into practice ().

Figure 4. The TOPSOFT team in 2001. Eyram Tawia is the second right. © Eyram Tawia. 2016. Uncompromising Passion.

Next to access to television, access to the internet was an important development during the childhood of the tech entrepreneurs. The tech entrepreneurs were among the first to use the internet in the mid-1990s. Like other Ghanaians in that period, they first got access to the internet at internet cafés (Zachary Citation2004, 13, 15; Burell Citation2012). The tech entrepreneurs said the internet gave them a sense of being part of a broader world beyond Ghana. In the early days, they mainly used it to send emails to friends and acquaintances abroad, tapping into transnational networks, just like their parents. They also looked up simple tutorials. From the late 2000s onwards, the internet provided them access to global role models of tech entrepreneurship, such as Steve Jobs (Apple) and Mark Zuckerberg (Facebook). In global media, these men were portrayed as largely autodidact and self-made men, who started with nothing, working from their own homes, and became successful through perseverance and creativity. As adolescents, the tech entrepreneurs could identify with these men because they considered themselves largely self-taught and limited in resources as well. These role models provided the adolescents with concrete examples of the wealth and success that could be achieved through this career path, inspiring them to become tech entrepreneurs. Moreover, the internet of the 2000s gave the tech entrepreneurs the possibility to further improve their IT skills, for instance through YouTube tutorials. The internet also allowed them to download and to familiarize themselves with all kinds of software, such as Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator, and gave access to all kinds of international games and movies, such as the newest superhero movies from Marvel and DC or the newest fighting games.

The access of the tech entrepreneurs to IT tutorials was particularly important for their careers, because it was difficult to get advanced IT skills in Ghana through other means. While all of the tech entrepreneurs obtained a university degree, only some (like Tawia) majored in computer and software engineering or computer science. The main universities in Ghana started to offer these majors in the mid-1990s. However, after the economic and political turmoil in the 1980s and then under a government that retracted public services in the 1990s, there was little support for these studies. Therefore, students got taught outdated coding languages, only had access to a few computers and had to do their coding on paper (Zachary Citation2004, 15, 16). In their final years, the more talented students, like Tawia, had progressed beyond the resources the university departments could offer and had to rely on online tutorials. Tawia, for instance, managed to develop a computer game for his final university project with the help of these tutorials.

The graduation of the group of tech entrepreneur friends from university coincided with a deteriorating economic situation in Ghana and increased opportunities offered by institutions in the tech space. The tech space slowly started to develop in Ghana in the mid-1990s; the liberalization of the economy not only attracted telecommunication companies like MTN and Vodafone, but also NGOs, which would later become active in the tech space. Moreover it attracted entrepreneurs from the US, Europe and the Ghanaian diaspora, who wanted to explore new business opportunities. The latter funded the first tech companies, like Soft (a company that made software for web cafés) and BusyInternet (an internet café with bar, restaurant and office space for start-ups) in the 1990s (Zachary Citation2004, 10–12).

In the 2000s, several institutions were established that aimed to develop the IT skills and entrepreneurial skills of young middle-class Ghanaians. In 2002 Patrick Awuah, a Ghanaian returnee, established Ashesi University in Accra; a private university only affordable for the fortunate few, which blended software engineering and business studies in a liberal arts setting. In 2004, the Ghanaian government, supported by the Indian government, established the Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre in Accra to teach Ghanaians the computer skills required by government agencies (Zachary Citation2004, 10, 18, 19, 23). In 2008, the Meltwater Foundation, the NGO of the multinational Software as a ServiceFootnote1 Company Meltwater Group, established the Meltwater Entrepreneurial School of Technology (MEST) in Accra, followed by the Meltwater Incubator in 2010. Initially,Footnote2 MEST offered who they considered to be Ghana’s most talented recent university graduates a two-year program in which they were taught the business, software and communication skills deemed necessary by the Foundation to become successful tech entrepreneurs. After these two years, the Foundation offered seed investment, a place in the Incubator and the opportunity to make use of the network and knowledge of the Meltwater Foundation to the students the Foundation considered to have the best ideas, in exchange for a minority share and decisive vote in company decisions. In 2013, Hub Accra and iSpace started to run programs similar to the Meltwater Foundation; they offered office space, possibilities for skill development and access to networks and funding opportunities. However, compared to the Meltwater Foundation, these Hubs were less selective and had only limited access to global networks and funding opportunities. Therefore, they mainly attracted lower middle-class tech entrepreneurs, who did not have the qualifications to be allowed into MEST.

From the mid-2000s these institutions, together with transnational NGOs and corporations, such as MTN, Vodafone, USAID and the GhanaThink Foundation (an NGO of upper middle-class Ghanaians from the diaspora) also started to organize events for tech entrepreneurs, such as app competitions. At these events NGOs and corporations encouraged the tech entrepreneurs to use technology, in particular apps, to address ‘local African’ issues and to present ‘local African’ content in the hopes that this would appeal to the growing market of African mobile phone owners. They were also encouraged to use technology to become globally successful. This was reflected in the set-up of these events; winners of app competitions often received the opportunity to present their app at regional or global finales, or prestigious conferences in Europe or the US.

For many young urban professionals, until the 2000s, working in private corporations was considered most prestigious, with working for the government as the second best option. From the 2000s onwards tech entrepreneurship increasingly became a career path to solidify the tech entrepreneurs’ middle-class status. The emerging institutions and events fitted well with the tech entrepreneurs’ previous experiences and aspirations. They tapped into the tech entrepreneurs’ education, IT skills, association of success with global or transnational networks, admiration for global examples of tech entrepreneurship, and appreciation of global media and technologies. To people like Tawia, these institutions and events provided the possibility to further enact their childhood dreams. With the improved IT skills and access to capital provided by these institutions they could start their own technology companies. All the tech entrepreneur friends of Tawia made use of one or several of the programs mentioned above. Tawia had applied to the MEST program, but instead of being selected as a student, he was approached to become a lecturer. He eventually received seed funding for his company from the Meltwater Foundation. During the fieldwork, Leti Arts was still located in the Meltwater Incubator.

Tech entrepreneurs continued the same patterns of media consumption developed during their childhood and adolescence. They downloaded the newest versions of Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop, the newest tutorials, watched the newest DC and Marvel superhero movies and series (Arrow, Flash), played the newest fighting games, watched Japanese anime (animated series) and all kinds of American series, such as series focused on entrepreneurship (Shark Tank). While more and more Ghanaians have access to the internet, the consumption of these media was still only affordable to the more privileged. Not only is downloading still a slow and expensive process, but also the hardware necessary to store these programs (PC or external hard drive) was very expensive. At the same, they asserted that they rarely watched Ghanaian movies or series produced by local television stations. Tawia explained that the ‘quality’ of these movies and series was ‘low’. According to him the plots and special effects of these movies were not as good as the movies produced in Hollywood. The expression ‘low quality’ was central in the explanations of the tech entrepreneurs concerning Africa’s Legends and during the production process. They used this expression to refer to forms of public culture, from TV to comic books, they thought represented old-fashioned African aesthetics and design, influenced by Western agents and which did not live up to globally competitive standards. Therefore, something new and innovative was needed. The short history of this group of tech entrepreneurs makes clear that Leti Arts’ focus on superheroes and on ‘quality’ was influenced by stylistic and aesthetic preferences they developed during their childhood.

Producing ‘quality’: ‘new African’ aesthetics

The experiences of the tech entrepreneurs with digital media and digital technologies in the 1980s and 1990s directly informed the production of the aesthetics of Africa’s Legends. The constant reflection on these media and technologies during the production process in 2014, revealed that Africa’s Legends were a means to mediate the position of the tech entrepreneurs in Ghanaian society. The aesthetics of the African superheroes were developed by the artists in negotiation with Owusu and Tawia. In this process, Tawia had the final word. The development process was divided into several phases: After discussions about the background of the superhero in question, the artist would develop sketches using pen/pencil and paper. When satisfied, (s)he would upload these sketches onto Adobe Photoshop and/or Adobe Illustrator, to work on the colours, lining and shading, and to complete the image. In this stage, Tawia would step in to give directions; often he commented that the superhero should look ‘very muscular’, or that the artist should use ‘bright colours’ and draw ‘clean lines’. Tawia explained that he considered these features important characteristics of superheroes in the global comic book genre, particularly those of DC and Marvel comics. He also emphasized that he thought the use of digital technologies like Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator for the production of these features was crucial to assure their ‘quality’ and the creation of a ‘new African’ style.

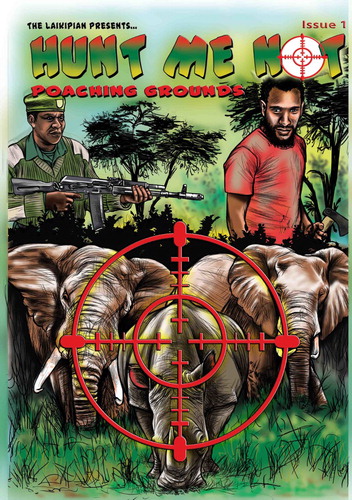

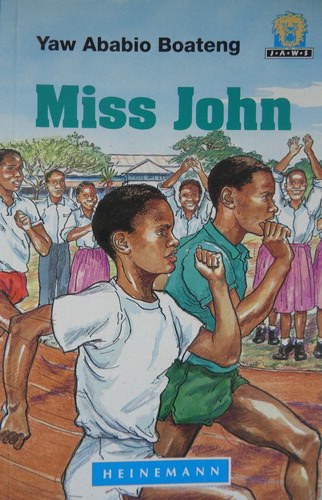

The reason why Tawia and Owusu connected the use of digital technologies to ‘quality’ and ‘new Africanness’ was explained by Owusu one quiet afternoon in the Leti Arts office. While the few people present were working in silence, Owusu suddenly became frustrated with the aesthetics of the recently published Kenyan comic called Hunt me not, which was forwarded to him by Kirinya from Kenya and which he was viewing on his laptop. Owusu ranted that Leti Arts should consider contacting the company that ordered this comic, because Leti Arts could deliver better quality. To explain himself further, he impulsively pointed at the Kenyan comic on his screen saying: ‘Look! This is African! Africa’s Legends is not African!’ A moment later Owusu realized that he had just denied the Africanness of Africa’s Legends so often celebrated by him and the team. He explained that he called the Kenyan comic African because the style looked similar to the images in the books he had borrowed from the children’s library at the university campus. He had come to appreciate this style as typically African yet of the ‘low’ quality mentioned before. This style featured ‘more sketchy’ lines, featured lots of green and red shades, and looked ‘hand-drawn’. To illustrate the similarities between Hunt me not and these books he used Google to look up one called Miss John. He emphasized that these kind of books portrayed the ‘low quality’ which was the ‘old’ African style, because they were produced by foreign publishers like MacMillan and Heinemann, and as such depicted Africa and Africans as imagined by Westerners ( and ).

This moment revealed that the tech entrepreneurs used digital technologies as a tool to negotiate their Africanness in a globalized world. The digitally produced ‘new African’ style directly opposed the African images from their childhood, and in doing so, the agency of Westerners to shape African aesthetics. At the same time, this style was inspired by, and meant to be competitive with, the style of DC and Marvel Comics. This new style and the use of digital technologies was thus a means for the tech entrepreneurs to seize control over the creation of African aesthetics and to show that these aesthetics could be of the appropriate calibre to be globally competitive and, moreover, that African designers are players in the global arena.

These global aspirations were reflected in the use of elements of African heritage from different times and places across the continent in the design of the superheroes. During a car drive to a business meeting, Tawia explained that he chose to develop heroes that were inspired by characters like Kwaku Ananse (Ananse), the Maasai (Wuzu), or the eighteenth century Southern African monarch Shaka kaSenzangakhona (Shaka Zulu), because he considered these characters to be well-known both in Ghana, Africa and beyond the continent. He thus chose these characters to let the superheroes appeal to a large audience. He thought that these heroes would have the most marketing potential to develop Africa’s Legends into a global brand.

While the ‘new African’ style of the African superheroes was inspired by Marvel and DC Comics, Tawia and his team also spent a lot of time on making the African heroes look ‘African’ in order to distinguish them from Marvel and DC. To make this process clear, we will zoom in on the superhero Ananse. One day in the Leti Arts office Tawia was searching for his old hard disk and stumbled upon some earlier experimental versions of Ananse. He commented that some of these versions had been rejected because the team had considered them to look too much like Spiderman – one of Marvel’s superheroes who is able to climb walls and shoot spider webs ( (a)). He explained that for instance the Ananse portrayed in (b) was rejected because he was bald, just like Spiderman when he had his suit on. The Ananse in (c) was also considered too similar because the artist had portrayed him shooting webs as a superpower, just like Spiderman. Eventually, the team decided that the Ananse in (d) would become the official version. Influenced by the Ghanaian notion that elders should be respected, this Ananse had grey hair to emphasize his wisdom. He also had gloomy eyes to signify that his superpower was the ability to create webs of illusions. Tawia explained that these two features made Ananse different from Spiderman in two ways: Ananse had a different haircut and a different superpower than Spiderman. He further emphasized that the team added other African features to Ananse, such as his wide pants and bare feet. Also, all the African superheroes had a dark skin colour.

Figure 7. (a) Marvels’ Spiderman © Marvel Entertainment, LLC. (b) Rejected depiction of Ananse © Leti Arts. (c) Rejected depiction of Ananse © Leti Arts. (d) Official version of Ananse © Leti Arts.

In a later conversation, Owusu added that the ‘origin story’ of the African superheroes was also consciously Africanized. The origin story is a common narrative structure in the comic book genre, which explains how the character became a superhero and/or received superpowers so as to create a connection to ever-continuing story lines. According to Owusu, in the DC and Marvel Comics, most superheroes had received their superpowers through scientific accidents or experiments. For instance, Spiderman received his superpowers after being bitten by a radioactive spider. As an Africanizing mechanism, the Leti Arts team had developed origin stories which narrated that the African superheroes got their superpowers through possession. The origin story of Ananse featured an ordinary Ghanaian school boy who got possessed by Kwaku Ananse’s spirit, and thus developed superpowers. Owusu imagined Shaka Zulu to be a South African police officer, whose body and mind were taken over by the spirit of Shaka kaSenzangakhona when in danger. In this state, Shaka was able to summon his Ghost Army.

Other producers of African superhero comics on the African continent had also combined elements of DC and Marvel Comics with divine and/or magical elements derived from African folklore. Inspired by the Batman and Superman comics he read as a child, the Ghanaian-Kenyan cartoonist Frank Odoi developed comics about the African superhero Akokhan, published in Kenya’s major dailies between 1995 and 2011. Odoi explained that since the power of DC and Marvel’s superheroes was derived from scientific sources, he decided to explain the superpowers of Akokhan through magic (Omanga Citation2016, 263, 264). The Tanzanian artist Amani Abeid developed comics about the African superhero Osale. In this figure, Abeid combined the troubled, difficult character of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Night Batman, with what he considered ‘traditional magic’ (Casely-Hayford Citation2016, 296, 297).

During discussions in the office, it became clear that the Africanizing features of the heroes were not only a means to distinguish heroes from DC and Marvel, but also connected to developments in the Ghanaian media landscape. In the mid-1990s, Pentecostal churches used the liberalization of Ghana’s media to buy airtime with new private media stations. Due to this strategy, large financial resources and the dominance of Christians amongst media professionals, these churches managed to grow in popularity and to become dominant in the Ghanaian public sphere (De Witte Citation2005, 283, 284). A central theme in the Pentecostal churches is that elements of traditional culture and religion, such as libation, are represented as problematic in that they invoke the presence of evil spirits and demonic powers in the public domain (Meyer Citation1999), and are thus a representation of heathendom. Also, the objects, images, sounds and performances nationalized by Sankofaism were considered as potentially containing ‘demonic powers’ (De Witte and Meyer Citation2012, 48–50). Owusu, who was an active member of one of the Pentecostal churches in Accra, explained that at first he had considered the possession of Ananse and other superheroes ‘too demonic’, thus articulating a Pentecostal point of view. Eventually, he and the team agreed on possession, because in his words, science was ‘too unauthentic’, since ‘African folktales are usually about divine powers’. Moreover, he asserted that it was just a ‘cultural’ and not a ‘religious’ element, that through comic books the cultural aspect was firmly positioned as entertainment. This strategy – positioning objects of cultural heritage as entertainment – was used by many Ghanaian media as a means to downplay the demonic powers Pentecostals warned of (De Witte and Meyer Citation2012, 47 and 60).

Moreover, Tawia explained that the superhero Ananse was specifically inspired by By the Fireside, the television programme that introduced his generation to the Anansenem. According to him, Africa’s Legends – specifically Ananse – was the current way to introduce these stories to children. He thought that the ‘new African’ style and the format of the games and comics, were crucial to generate interest in current youngsters. Owusu and Tawia also asserted that Africa’s Legends were ‘modern’ day superheroes. Because they were ‘modern’ they had suits that creatively combined elements from DC and Marvel comics with elements of African history and folklore, instead of being a historically accurate representation of history. In the narratives of the comics featured in the app, superheroes like Ananse and Shaka were also framed as using their super powers to battle present-day crimes in African cities. So similar to Sankofaism and programs like By the Fireside, Leti Arts firmly rooted African history and folklore in the present and used it to address present-day issues.

In the Leti Arts office, Tawia, Owusu and their tech entrepreneur friends often discussed and complained about what they called the mentality of Ghanaians. According to them, Ghanaians appreciated foreign products before African products – for instance, rice was imported while it could just as well be produced in Ghana. Similarly, according to them, Ghanaians often did not believe in the capabilities or capacities of Ghanaians until these talents were recognized and endorsed by transnational actors or on an international platform. Owusu mentioned once, for example, how the Ghanaian news coverage of the achievements of a ‘Ghanaian astronaut’ illustrated this mentality. The talents of this Ghanaian had only been recognized by the Ghanaian media after he had received opportunities and had become successful in the US. Owusu explained that the content and timing of this news revealed that this Ghanaian had probably not been encouraged by fellow Ghanaians to fulfil his dreams before his international success. This sentiment of the tech entrepreneurs ran deep; they felt strongly about what they considered a deferential attitude that prevented Ghanaians from realizing their full potential. In Tawia’s words, Africa’s Legends showed that ‘quality’ could be produced ‘from Africa, instead of for Africa’. Moreover, it symbolically emphasized that Africans, based on their history and culture, had the power to address their present day issues – just like the African superheroes. So, in short, quality and style stood for pride of African heritage and symbolized being a self-confident African in a globalized world.

Africa’s Legends: distribution, reception and reflection

To emphasize that Africa’s Legends mediated particular upper middle-class aesthetics and aspirations, it is important to consider the distribution and reception of the app. When Owusu and Tawia mentioned that Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop allowed them to produce ‘quality’, they not only referred to the production of a style they deemed suitable for African and global audiences, but also to the fact that these digital technologies allowed them to produce this same style for different media. Elements of the ‘new African’ style, such as the ‘thin lines’ or the ‘bright colours’, could theoretically be produced with pen/pencil and paper. However, the digital images produced in Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator could easily be adjusted to different (digital) platforms and sizes, without losing their ‘quality’ features, like their thin lines, whereas this was more difficult with hand-drawn images. Tawia explained that he preferred the development of the aesthetics of Africa’s Legends in Adobe Illustrator instead of Photoshop, because it assured better ‘quality’. In Adobe Photoshop, images consist of pixels. When these images are expanded, clean lines or bright colours can become granulated. This problem does not arise when one develops images in Adobe Illustrator, because this program uses vector graphics. The images of Africa’s Legends were not only featured in relatively small sizes in the app, or in the app store, but were also portrayed on banners and posters in the office and/or during expositions, or were featured on flat screens during TV interviews or presentations at events in the tech space. The calibre of the ‘new African’ style in different formats and sizes was thus crucial for the (digital) distribution and promotion of the app across Ghana, Africa and the rest of the world. The tech entrepreneurs considered the distribution of their app amongst all these different channels (from YouTube to Al-Jazeera Africa to the Game Developers Conference in San Francisco, US) as a means to reach their desired global audience. Digital media thus mediated the tech entrepreneurs’ global aspirations, and Adobe Illustrator and Adobe Photoshop functioned as tools to achieve this aspiration.

While the tech entrepreneurs aspired to target continental African and global audiences, the consumption of the app was halted in Ghana by the perceptions different groups of middle-class Ghanaians had about the Africanness and the quality of the app. One of these groups consisted of young middle-class men, and occasionally women, who considered themselves to be ‘gamers’. These young urban professionals spent much of their leisure time and income on playing the latest games produced by international companies, such as the FIFA (a football game), fighting games and Online Battle Arena (MOBA) games like League of Legends and Dota 2 on their desktops, laptops, PlayStations and XBOXs. While those who had played Africa’s Legends on their phone appreciated the aesthetics of the app, they thought that the game was not up to standard. The game in the app was not addictive enough and the app did not include enough content compared to what they were used to. So since this group assessed quality in a different manner than Leti Arts, their opinion about the global reach of the game differed from the tech entrepreneurs.

A common interpretation of the African Heroes among less privileged young middle-class Ghanaians was that the heroes did not look African, or not African enough. In some instances, they thought the heroes were not African because they were ‘too muscular’, their lining was ‘too clean’ and their colours were ‘too bright’, and instead should have ‘more sketchy lining’ and ‘more painted-like’ colours. In essence, they used the ‘old African’ style as a point of reference. Others considered Africa’s Legends to be un-African because they considered the aesthetics to be too influenced by the comic book genre, and therefore not historically and culturally accurate. For instance, they considered the upper part of Ananse’s suit to not be authentically African, because they thought that ‘an African in the past would never have worn something so tight’. The image of a spider on Ananse’s breast was also considered un-African because it looked too much like Spiderman. A hero like Shaka () was perceived as less inauthentic and un-African because only his mask was seen as an element of the comic book genre. Other features, like his bracelets, loincloth, bare feet and chest, were perceived as authentic. On Leti Arts’ social media some also expressed the opinion that the only thing that made the heroes look African was their skin colour: ‘Leti Arts you guys are doing a great job, but the characters you are creating does [sic] not look anything like African except their complexion. Maybe you can do something about their costumes it will be great’ (Leti Arts Citation2014). These interpretations are in line with other debates about Africanness in the media. The Ghanaian media station TV Africa, for example, produces programs about African heritage in which Africanness was understood as free from Western influences (De Witte and Meyer Citation2012, 57) and hence serves as a point of reference to what is or is not authentically African in contemporary Ghana.

At the same time, the app resonated with upper middle-class Ghanaians from similar backgrounds as Tawia, Owusu and their tech entrepreneur friends. For instance, Amma Samuel,Footnote3 the child of a university lecturer and a university lecturer herself (just like Tawia and Owusu), said about Africa’s Legends: ‘It’s exciting to see something emerge out of Africa. Even though they are supposed to be fictional, they give us hope. They are African superheroes, so we can be superheroes too.’ To her, the African superheroes were a product from Africa, highlighting the capacities and capabilities of Africans.

Africa’s Legends was also very well received at events in the tech space in Accra, such as at app competitions. At these events, Tawia (and sometimes Owusu) pitched the app for a jury, often consisting of employees of transnational corporations and/or NGOs, and an audience often consisting of a mixture of tech entrepreneurs, fellow contestants, and employees of transnational NGOs and corporations. Africa’s Legends was often introduced on wide screens, accompanied by dramatic music that seemed to highlight the mightiness of the heroes. Tawia also often emphasized that Africa’s Legends consisted of elements of ‘local African’ history and folklore and was meant to target ‘local African’ and ‘global audiences’. This presentation appealed to the jury members, whom were looking for ‘local content’ but also for apps that could compete globally. Tawia and his team won many competitions with Africa’s Legends. During the fieldwork, Tawia for instance won the Vodafone app challenge in Accra. As a reward, he competed in the global app challenge in India. When he won this challenge as well, he was awarded access to a prestigious event in Barcelona, Spain. These successes also often resulted in news coverage by local media and transnational media, showing that ‘new African’ aesthetics helped Tawia and his company to get access to the global.

Owusu and Tawia often reflected on their own aspirations and the critique they had received. As a response to the idea that the aesthetics of the African superheroes were not ‘authentically African’, the tech entrepreneurs explained on their blog that the background of the superheroes was not chronological:

Sometimes there is more to a story than meets the eye. Our characters have complex, evolving personalities and their background stories are not chronologically depicted. Therefore, what you see now is a point in time of the story of these characters. (Leti Arts Citation2014)

Back in the day, when I was young, I saw my geeky cousins play videogames and comics. It got me so obsessed with videogames and comics and I also wondered why this wasn’t done from this part of the world. So I grew curious to teach myself to make this happen. (Innovation Ghana Citation2013)

Conclusion

The style of the African superheroes in Africa’s Legends demonstrates how technology entrepreneurs use digital technology and digital media to articulate what it means to be Ghanaian and African in a globalized world. Because of their middle-class backgrounds, the tech entrepreneurs were the first to grow up with digital technologies and digital media in the 1990s, and the first to enter the tech space in the early 2000s. During their childhood, technologies mediated their aesthetic development and aspiration, from local TV programs focusing on African heritage, to Asian series, to American comics and other globally circulating popular culture. Moreover, both the parents and digital technologies taught the tech entrepreneurs to associate success with access to transnational networks or global markets. Also, the parents stimulated them to acquire IT skills before it was available in Ghana and to enact their aspirations. In other words, (digital) technologies both shaped and articulated the upper middle-class-ness of this privileged group.

The production of the aesthetics of the African superheroes in Africa’s Legends was informed by their social position and taste. The Leti Arts team combined elements of African history and folklore with elements from DC and Marvel Comics. They used digital technologies like Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator to create the quality they needed to express a new Africanness. These ‘new African’ aesthetics, which were translated into ‘clean lines’ and ‘bright colours’, contrasted the ‘old’ African style, which is characterized by the typical ‘hand-drawn’ lines, with ‘more painted like colours’ and ‘sketchy lines’ characteristic of the widely available (comic) books published by Heinemann and MacMillan Publishers across the continent since colonial times. To them, this new Africanness is of a calibre that can stand the standards of the new century and thus attract both an African and global audience.

The design of Africa’s Legends is an articulation of a very specific group in Ghana’s social landscape and that explains the varied reception of the African superheroes, from being celebrated by a globally oriented tech space to apprehension by local gamers. Digital technologies do not simply circulate products, the products still need to be appreciated in order to circulate successfully. The lukewarm reception of Africa’s Legends in Ghana can be explained by the diverging appreciation of Africanness. The new style of Africa’s Legends is not an expression of African heritage in a contemporary design, it is a signifying practice that reveals more about class aesthetics and aspirations. Nevertheless, Africa’s Legends is aimed at fostering pride in African heritage and self-confidence in Ghana and in a globalized world where, according to the producers, both Ghanaians and others validate global products over local ones. Ultimately, the superheroes challenge presumptions about Africa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 As Software as a Service (SaaS) company provides licensed, centrally hosted software on a subscription bases, such as messaging or management software. Meltwater Group for instance offers a social media measurement tool (Meltwater 2016).

2 Since 2015 the MEST program has gradually been adjusted. In 2016 MEST offered a one-year program to students from Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya and South Africa.

3 Participant interviewed in September 2014. Her name is a pseudonym.

References

- Behrends, Andrea, and Carola Lentz. 2012. “Education, Careers, and Home Ties: The Ethnography of an Emerging Middle Class from Northern Ghana.” Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie 137 (2): 139–164. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41941021.

- Burell, Jenna. 2012. Youth in the Internet Cafés of Urban Ghana. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Casely-Hayford, Gus. 2016. “Amani Abeid and Paul Ndunguru: the archaeology of a superhero.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 28 (3): 292–298. doi: 10.1080/13696815.2015.1053801

- Coe, Cati. 2006. Dilemmas of Culture in African Schools: Youth, Nationalism and the Transformation of Knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Coetzee, Carli. 2016. “Afro-Superheroes: Prepossessing the Future.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 28 (3): 241–244. doi: 10.1080/13696815.2016.1168082

- Comaroff, John, and Jean Comaroff. 2009. Ethnicity, Inc. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- De Witte, Marleen. 2005. “Insight, Secrecy, Beasts, and Beauty: Struggles Over the Making of a Ghanaian Documentary on ‘African Traditional Religion’.” Postscripts 1 (2/3): 277–300.

- De Witte, Marleen, and Birgit Meyer. 2012. “African Heritage Design: Entertainment Media and Visual Aesthetics in Ghana.” Civilisations 61 (1): 43–64. doi: 10.4000/civilisations.3132

- Ferguson, James. 1999. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambia Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Heath, Carla W. 1997. “Children’s Television in Ghana: A Discourse about Modernity.” African Affairs 96 (383): 261–275. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007828

- Heiman, Rachel, Carla Freeman, and Mark Liechty. 2012. “Introduction: Charting an Anthropology of the Middle Classes.” In The Global Middle Classes: Theorizing Through Ethnography, edited by Rachel Heiman, Carla Freeman, and Mark Liechty, 3–29. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Innovation Ghana. 2013. “Innovation Ghana: Leti Games.” Accessed 21 November 2016. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lJYhpXo8kn4&t=1s.

- Kente Games. 2016. “Ananse Rises.” Accessed 21 November 2016. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.kente_factory.ananse_rises.

- Kiro’o Games. 2015. “Press Kit of Aurion.” Accessed 21 November 2016. http://kiroogames.com/en/en/kiro-o-business/kit-press-of-aurion.html.

- Larkin, Brian. 2008. Signal and Noise: Media, Infrastructure, and Urban Culture in Nigeria. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Lentz, Carola. 2015. “Elites or Middle Classes? Lessons from Transnational Research for the Study of Social Stratification in Africa.” Working Paper of the Department of Anthropology and African Studies 161. Mainz: Johannes Gutenberg-Universität.

- Leti Arts. 2014. “Great Minds, Think Alike. Africa’s Legends Game and Marvel Puzzle Quest.” Accessed 4 December 2016. https://letiarts.wordpress.com/2014/04/14/africas-legends-game-marvel-puzzle-quest/.

- Leti Arts. 2016. “Africa’s Legends.” Accessed 7 November 2016. https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.leti.leticenter.intel.

- Liechty, Mark. 2012. “Middle-class Déjà Vu. Conditions of Possibility, from Victorian England to Contemporary Kathmandu.” In The Global Middle Classes: Theorizing Through Ethnography, edited by Rachel Heiman, Carla Freeman, and Mark Liechty, 271–299. Santa Fe: School for Advanced Research Press.

- Melber, Henning. 2013. “Africa and the Middle Class(es).” Africa Spectrum 48 (3): 111–120.

- Meyer, Birgit. 1999. Translating the Devil: Religion and Modernity among the Ewe in Ghana. IAL-series. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Omanga, Duncan. 2016. “‘Akokhan Returns’: Kenyan Newspaper Comics and the Making of an ‘African’ Superhero.” Journal of African Cultural Studies 28 (3): 262–274. doi: 10.1080/13696815.2016.1163253

- Osiakwan, Eric M. K., William Foster, and Anne Pitsch Santiago. 2007. “Ghana: The Politics of Entrepreneurship.” In Negotiating the Net in Africa. The Politics of Internet Diffusion, edited by Ernest J. Wilson III and Kelvin R. Wong, 17–36. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

- Shipley, Jesse. 2013. “Transnational Circulation and Digital Fatigue in Ghana’s Azonto Dance Craze.” American Ethnologist 40 (2): 362–381. doi: 10.1111/amet.12027

- Spronk, Rachel. 2014. “Exploring the Middle Classes in Nairobi: From Modes of Production to Modes of Sophistication.” African Studies Review 57 (1): 93–114. doi: 10.1017/asr.2014.7

- ThroneOfGodsDevs. 2016. “Throne of Gods.” Accessed 7 November 2016. https://www.facebook.com/ThroneofGodDevs/.

- Zachary, G. Pascal. 2004. “Black Star: Ghana, Information Technology and Development in Africa.” First Monday 9 (3). http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue9_3/zachary/index.html.