The setting

In September 2016 a group of scholars, artists and students gathered in the gallery space of the Stellenbosch University Museum in South Africa for a roundtable on art, activism and social justice. Most of the academics in the room were participants of a workshop on ‘Political subjectivity in times of transformation: Classification and belonging in South Africa and beyond’. This was the opening night of our workshop – concurring with the launch of ‘Open Forum’, an arts initiative that called on students, artists and activists to produce works that would actively intervene in the university space and thereby challenge the stifling status quo (). At that time, South African students had been out on the streets for more than one year, protesting against the ongoing marginalization of black people on campus and the perpetuation of colonial and neoliberal modes of knowledge production (Booysen and Godsell Citation2017). Students were demanding profound changes – and they wanted to be taken seriously.

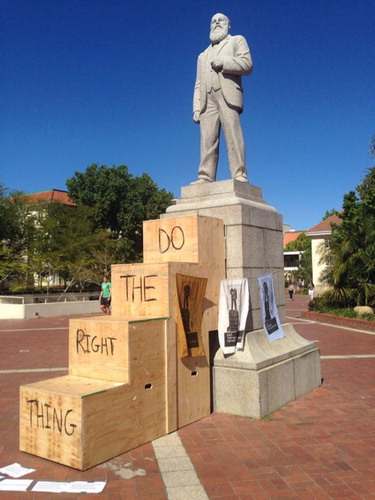

Figure 1. Flight, Nicolene Burger. Photograph by Open Forum Collective, Stellenbosch University, 2016. The staircase in this work can be viewed as a gesture to encourage Stellenbosch university’s patriarchal and racist past represented by the statue of Jan Marais, the institution’s first major benefactor to step down. The staircase also symbolizes a call for new leaders to step up in order for new and divergent histories to be archived and for new knowledge to be produced. Nicolene’s sculpture was installed on the university’s square, Die Rooiplein in October 2016 but was removed soon afterwards by the Campus Protection Services.

Figure 2. Flight, Nicolene Burger. Photograph by Open Forum Collective, Stellenbosch University, 2016. The armed, private security firm that students refer to as the ‘Men in Black’ surround the sculpture a few minutes after it was installed on the Rooiplein. Their apparent deployment here was to protect the sculpture of Jan Marais.

Figure 3. Silencing Me, System!, Grace Peterson, 2016. Photograph by Open Forum Collective, Stellenbosch University, 2016. No: Silencing Me, System! is a multimedia performance that was first performed at the Stellenbosch University Museum in November 2016. The performance was set against a montage of projected photographs collected by the artist during the #FeesMustFall student protests in October 2015. At the start of the performance, the photographs are clear and in focus but as the performance progresses they become increasingly blurred to shift the audience’s attention onto the performers who can be viewed as extensions of the protesting students. Peterson draws attention to the violent practice of silencing dissident voices at Stellenbosch University and the impact this had on the psyche of the student body.

Figure 4. Video Still from the documentary Mbokodo Lead, produced by Retha Ferguson for Open Forum, 2016. The woman in the frame is Nomzamo Ntombela, #FeesMustFall leader and first black woman president of the Student Representative Council (SRC) at Stellenbosch University for the 2016/2017 term.

Figure 5. The Dustbin, Stephané Conradie. 2016. Photograph by Greer Valley, 2017. Stephané Conradie was arrested for setting a bin alight near the university campus during the 2015 #FeesMustFall student protests. She was released on bail and was summoned to appear in front of a judge at the Stellenbosch Magistrates court. Her ‘sentence’ was that she should write an essay explaining her reasons for setting the bin alight, which she subsequently did and the charges were dropped. For her Open Forum performance in 2016, she produced 500 pamphlets of this essay and distributed them to passers-by at the site where she was arrested. This piece also suggests something about punishment, what kind of punishment is reserved for whom, and the artist has herself been critical of this. For example, outsourced workers who had burned bins and street furniture during the same time period as part of the #EndOutsourcing protests were fired from their positions.

Figure 6. The Dustbin, Video Still, Stephané Conradie. 2016. Photograph by Open Forum Collective, Stellenbosch University, 2016.

In that light, Open Forum’s call to occupy the spaces of the university and its surroundings in order to make a difference resounded with our academic interest in political subjectivities. This interest stemmed from our shared concern for the manifold processes through which individuals and groups gain or lose their voice, claim positions to speak from, make noise, or become silenced in everyday life and politics. We started from the assumption that becoming ‘part of the game’ (Frazer Citation2010, 365) of politics, and thereby becoming positioned as a political subject requires to be recognizable. Such recognition is always closely related to practices of classification, which can be both enabling and hurtful. We consequently asked about the interfaces of mis/recognition through which subjectivities are formed in relation to state institutions, other authorities or alternative modes of belonging. What are the dynamics between the making and marking of differences through which subjects come into being? How do formal categorizations intersect with practices of belonging? How do they impact on both affective and lived experiences of individuals in the everyday? What role do they play in broader political debates and problematics related to citizenship and other forms of entitlement? By engaging the concept of political subjectivity, the workshop aimed to bridge these registers. We interrogated both historical remainders and contemporary forms of the classificatory practices around ‘making up people’ (Hacking Citation1986) as well as their formative effects on possibilities of personhood (Krause and Schramm Citation2011). We were particularly interested in the articulations of new forms of political subjectivity in times of social and political transformation. How are new modes of political subjectivity informed (and perhaps constrained) by knowledge genealogies of the past, but also how do they open up a creative space to venture into the future?

The Stellenbosch University Museum, oddly positioned between art collection, institutional archive and exhibition hall, was a fitting space to start this conversation.Footnote1 As an institution, the University of Stellenbosch was deeply entrenched in apartheid ideology and education, as it was here that the intellectual foundations for the politics of apart-heid and racial segregation were laid.Footnote2 In the museum space, the classificatory load of apartheid was cutting through the ‘smell of dust’, as one of the roundtable participants put it. For example, the ‘anthropology’ section of the museum still follows a representational strategy that evoked distinctive and ahistorical ‘traditions’. This mode of display goes back to Nicholas van Warmelo, the government ethnologist who had classified Bantu speakers into 10 fundamental ‘tribes’. Van Warmelo’s division had ‘played a critical role in the creation of apartheid bantustans’ (Dubow Citation1995) and the accompanying policies that were installed to keep non-white people out of the cities and out of public institutions, including the university. In contrast to the apparent timelessness of the ethnographica, the ‘cultural history’ exhibit used to display historical artefacts associated with whiteness (Davison Citation1990). Until recently, these included the desk of D.F. Malan, the first Prime Minister of the apartheid state and former chancellor of the University of Stellenbosch. Although the desk and other paraphernalia have been removed from the museum, the spirit of Afrikaner nationalism is still noticeable in Stellenbosch. Twenty-plus years after the democratic transition, Stellenbosch University counts as one of the least transformed institutions of higher education in the country.Footnote3 This specific situatedness made the question of critical intervention and the matter of political subjectivity in the sense of gaining voice, making noise and resisting silence all the more pertinent for our participants.

As we were listening to the introductory remarks, which located the roundtable discussion within those wider debates, the event was disrupted by a strange noise: a saxophone playing and loud cries calling out from different parts of the hallway. The sound floated through the building, deflecting, overlapping, stopping abruptly and starting again. We did not see anybody (at first) and we were unable to identify a clear voice or to make sense of what was being said. We were all stirred – and felt a mix of excitement and unease. What was going on? To whom did the voices belong? What kind of disruption was this? Would students come in to literally occupy the space, perhaps terminating our opening event? When the noise moved closer, we recognized the people. They were members of the arts collective ‘Is this a protest?’. Their performances aim to disrupt conventional social routines – be it an arts auction or an academic seminar. They play on the register of protest, but deliberately choose the artistic framework, thereby creating unique effects that challenged the distinctions between art and activism, participation and critical analysis.

The questions their performance raised had broader significance for our conference as a whole: What makes a disruption effective and to what ends? How can a performance-based practice make change tangible? In what ways does an artistic intervention constitute an ‘act of citizenship’ (Isin and Nielsen Citation2008) and thereby mark the articulation of political subjectivity? If decolonization was not just a matter of ‘filling the space [of the university] with black bodies’ (roundtable participant), it had to resonate with people’s everyday struggles, their desires and political aspirations. However, these dynamics do not only apply to protest settings but have broader implications. In what follows, we take up the sonic metaphor of resonance to rethink the concept of political subjectivity and to explore how it takes shape in the different contributions to this special issue. For us, ‘resonance’ provides a way of examining historically contingent processes of subjectification, including the strong amplifications, refractions, interferences and silences that mark it. Moreover, resonance also points to the relationality of political subjectivity, which always needs a feedback to take hold. In that sense, resonance reminds us of the dynamics of classification and belonging from which we started. Finally, resonance also implies a point of connection and affective engagement.

Multiple resonances: voice

Let us begin with voice. In many ways, the process of political subjectification is described as a gaining of voice. This implies a mutual dynamic of interpellation, articulation and recognition – calling out the subject, making it recognizable or known, and thereby opening the space for acting along and against the invoked categorizations (Butler Citation1990). For Hannah Arendt, the only possible way to gain political voice was through formal citizenship that granted ‘the right to have rights’ (Arendt Citation1951). Since then, writers on citizenship have acknowledged how the scope of rights-granting bodies of authority and discursive tropes has widened considerably (Frazer Citation2005, Citation2010). The proliferation of NGOs, medical professionals, diasporic groups, or global social movements has produced new political configurations and new constellations of political participation and recognition (Merry Citation2006; Trouillot Citation2001). Within these configurations, practices of claim making happen on multiple levels. Oftentimes, they are articulated and contested right at the interface of such multiple frames of reference, as some of the contributions to this special issue show.

For example, in the case-study by Aminata Mbaye, it is the tropes of global and local Islam, international human rights discourse, queer activism and the global health categorization of MSM (men having sex with men) that shape the ways in which queer people in Senegal gain a voice in the face of moral ostracization and public persecution. Kristine Krause analyses how ‘disability’ is enacted in relation to and in resonance with different discourses and institutions across different scales.

Gaining voice is also about becoming visible in the midst of discourses which as yet have no words for the position of the group concerned. Thus, for the community members from the township of Delft in Cape Town whom Joanna Wheeler has been working with, gaining voice was a twofold process of breaking silence. On the one hand, it concerned the sharing of experiences of personal trauma in the wake of daily routines of violence, i.e. the very ability to speak. On the other hand, it was about making their voices heard by local and provincial government, or, in other words, about speaking out from the margins.

However, it is clear that ‘gaining voice’ is not a straightforward process. After all, classifications are always entwined with processes of forceful exclusion (Bowker and Star Citation2000). They may entail problematic reifications, but also carry onward the poison of the past. This dynamic is captured in Stuart Hall’s suggestion to think of identifications as ‘suture’: the sore covering of wounds that stem from misrecognition and misrepresentation (Citation2000, 19). Kristine Krause builds on Hall and feminist writings on multiplicity in analysing how gaining a voice via disability can be simultaneously enabling and granting access to rights and resources, but also fixing the subject into a position of minder and less, i.e. somebody to be cared for. Thinking political subjectivity as articulations of different becomings helps to do justice to these tensions. In other cases, there is less ambiguity, since the privileging of collective voice often marks the violent suppression of heterogeneity within. This is demonstrated powerfully by Zethu Matabeni in her discussion of the exclusive politics of gay Pride in Cape Town.

Moreover, addressing the violence of classification in the past is a difficult process that may produce new frictions in the present. This point about the twisted temporalities of political positionality is developed by Lenore Manderson in her analysis of Brett Bailey’s controversial performance ‘Exhibit B’, which restaged colonial tableaux with life actors, thus reproducing the trope of the human zoo and a white gaze on black bodies. While the intention here was a critical interrogation of past violence and present-day racism, Bailey’s visual and discursive strategies did not resonate with some audiences, especially black activists, thereby leading to strong dissonances and protests.

Multiple resonances: noise

Such dissonance points to another facet of political subjectivity that came to the fore during our opening event. Here, the soundscape that the performance collective had created strongly interfered with the ordered choreography of the roundtable discussion. The irritating effect that emanated from the performance mirrored a frequent dynamic of protest, where issues and grievances may be concrete, but their expression would not necessarily rely on clearly articulated voice. Instead, protest may rely on noise as a way of disrupting a perceived status quo. In South Africa, such forms of protest have a long history throughout the anti-apartheid struggle and they continue to influence the ways in which political subjectivity takes shape (Brown Citation2015; Robins Citation2014; Von Schnitzler Citation2016). Whereas one could say that the notion of voice is in deliberate conversation with categories of difference, noise is about making a difference through action. This is what Engin Isin (Citation2012) and Jacques Rancière (Citation2004) have in mind when they argue (contra Arendt) that political subjectivity is not the precondition for political action but rather its result. For both of these authors, an event becomes a political act when it interrupts the ordinary and thereby interferes with the status quo. Therefore, as in the case of Cape Town Pride discussed by Zethu Matabeni, a demonstration in itself is not necessarily a political act, especially if it follows a well-established repertoire of public appearance or even affirms an exclusive, consumerist agenda. In contrast, as Matabeni shows, the interruption of the demonstration by black lesbian activists does constitute such an act, and so does their collective appropriation of a luxury toilet space in an inner-city shopping mall.

However, noise is not only a register of protest. It can also be part of a violent discourse that seeks to silence other voices. This becomes particularly clear in Mbaye’s paper, when she discusses the shrill exposure of an allegedly ‘gay marriage’ in Senegalese tabloid papers. As a result of the expose, some of the men in the photographs were imprisoned. Noise and classificatory violence can thus be threatening, cutting people off from political articulation as well as from their political subjectivities.

Multiple resonances: silences

Silences that demarcate the limits of political subjectivity are therefore as important as noise that is associated with the interruption of ordinary routines and spaces. In this special issue, three aspects of silence are addressed. First, there is silence that precedes or parallels the gaining of voice. This is emphasized in the contribution by Gavaza Maluleke, who is concerned with making visible particular subjectivities within homogenizing discourses of both the perpetrators and victims of xenophobia in South Africa. Her analysis centres on the everyday xenophobia experienced by female African migrants and local women married/partnered with African non-nationals, which are rendered invisible because of the dominant narrative that focuses on male violence, thereby reproducing a narrative about violence from poor, unemployed men. By teasing out the different forms of hostility these individuals face, Maluleke shows how the focus on men and physical violence silences the articulation of other subject positions.

Secondly, there is the silence of non-verbal, material and bodily dimensions of political subjectivity. Activist bodies may produce noise, but it is also their very physical presence (be it in the street, in the museum space or elsewhere), that has material effects and therefore makes a difference (see Butler Citation2015). When the focus shifts away from articulate voice and claim-making, specific mediations come into focus as important elements in the articulation of political subjectivity – an aspect that runs through all the contributions but is explicitly taken up by Kristine Krause, when she discusses the significance of a walking stick for simultaneously marking blindness as a form of excluded otherness and an element of distributed agency that allows for participation in that very collective.

Thirdly, and importantly, silence touches on the affective dimensions of political subjectivity. This is particularly addressed by Encarnación Gutiérrez Rodríguez who talks about mourning as a political act. While Joanna Wheeler’s paper on life on the margins of Cape Town discusses engaged storytelling as a narrative strategy to overcome grief in personal and collective acts, Gutiérrez Rodríguez’ notion of transversal mourning offers a more radical approach. In her case, it is the act of mourning itself through which new collectivities are formed and new politics imagined. Moreover, through her discussion of the responses to the escalating deaths of migrants in the Mediterranean it also becomes clear that silence can be deafening, pointing to exclusion, and potentially death: the abjected (Kristeva Citation1982) life is the life that cannot be grieved because it was not considered to be worth living in the first place (Butler Citation2006).

Thus, when we think about political subjectivity in relation to multiple resonances, we need to keep in mind that belonging is often linked to marginalizations and violent exclusions (Ahmed Citation2004; Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Moreover, political subjectivity does not correspond in a straightforward manner to claim-making, but it twists, bends and loops. It also stops, fails and falls apart. Therefore, we do not only consider acts of recognition but also instances of misrecognition and mismatch. It is in the tension between these poles that we locate the power of political subjectivity as an analytical concept.

The contributions

The eight papers that we have gathered in this special issue speak from different perspectives to the questions and issues raised above. As anthropologists, sociologists and political scientists our contributors share an interest in the dynamics of classification, belonging and exclusion, the legacies of past and present violence and the articulation of political claim-making in troubled times and spaces. South Africa continues to be a major frame of reference (for Matabeni, Wheeler and Maluleke), but the issues with which we are concerned can also be observed and discussed in other localities and transnational spaces. Thus, Mbaye’s paper is situated in Senegal and Krause’s in the UK and Ghana. The contributions by Manderson and Gutiérrez Rodríguez engage with entangled postcolonial histories on a wider scale. Their papers mark the overall trajectory of our special issue.

Lenore Manderson’s opening contribution Humans on show: Performance, race and presentation takes up the question of how to address the violence of race in the past without reproducing it in the present. Her piece discusses the performances Exhibit A and Exhibit B by South African theatre maker Brett Bailey, which were concerned with the exploitation and exclusion of (Southern) Africans in colonial situations, working among other things with tableaux staged by actors, resonating with the colonial tradition of exhibiting humans in zoos. The work, which has travelled worldwide, has created enormous controversy, with strong and sometimes violent protests, especially in Berlin, London, and Paris. Yet it is still on show. In analysing responses to it, Manderson questions differences between ‘seeing’ and display, and interrogates the capacity of irony to provide social critique in political theatre. She focuses on the problem of representation, taking into account contestations around authorship, social critique and the limits of form.

Gavaza Maluleke’s article Women and Negotiated Forms of Belonging in Post-apartheid South Africa addresses matters of violence, representation and political subjectivity from quite a different angle. Her paper is situated in the present of xenophobic violence against immigrants in South Africa. In mainstream discourse, these attacks are often presented as a conflict that mainly involves poor black men – to the effect that both the perpetrators and the victims of xenophobia are homogenized. Building on the works of feminist writers such as Chandra T. Mohanty, Maluleke argues that this uniform representation of xenophobia feeds from imaginaries of the nation which accept the bodies of women only in particular articulations as a valuable part of the nation building project. In analysing the experiences of women from other African countries, as well as that of local women married/partnered with African non-nationals, Maluleke questions what forms of belonging are negotiated and enacted in response to the different positionings of the women involved. She unmasks how the dominant discourse on xenophobia imagines the victim as an independent entity, who can be easily identified as ‘foreign’. She shows how being perceived as different is not fixed in status as a foreigner but becomes differently articulated via kinship, love choices, language and class, resonating with historical forms of inclusion and exclusion.

Questions of difference and the various processes of inclusion and exclusion in migration settings are also taken up in Kristine Krause’s contribution Speaking from the Blind Spot: Political Subjectivity and Articulations of Disability. In this case study, becoming recognized as disabled serves as a category of difference that allows for incorporation in multiple ways, which Krause theorizes as different articulations of political subjectivity, understanding political subjectivities not so much as acts of breaking scripts (Isin Citation2009), but as happening simultaneously along different scales ranging from everyday practices to institutionalized forms of support. These multiple enactments of subject positions can be seen as resonating in different forms of relating: in transnational activism and knowledge exchange, religious associations, in engaging with social workers and medical specialists or by tuning into colonial discourses of development.

The relational character of political subjectivity and the involvement of multiple scales of recognition also play a central role in Aminata Mbaye’s article Queer Political Subjectivities in Senegal: Claiming Rights within New Religious Landscapes of Belonging. Here, Mbaye sheds light on the different groups who give or withdraw recognition by relating to globally circulating discourses. More concretely, her paper examines how homosexuality has become a subject of political contestation in Senegal since the late 2000s, when new types of political demands and discourses relating to homosexuality emerged. Among these is the condemnation of same-sex intimacy by religious groups which is presented as an attempt to regenerate religious and cultural values. Moreover, the paper asks about the political claims and participatory politics of gay and lesbian Senegalese citizens in this hostile environment. Mbaye shows how current discourses on homosexuality in Senegal are embedded in a set of fractured representations of togetherness and belonging.

Fractured queer politics are at the centre of Zethu Matabeni’s paper Ihlazo: Pride and the Politics of Race and Space in South Africa’s cities. In her piece, she critically examines the contradictory ways in which pride has the potential of being a queer platform, in opposition to ‘regimes of the normal’, but is also performing a homogenizing and exclusionary identity politics in its dominant form. While pride has been closely associated with gay culture and liberation since the 1960s, it is not without contestation among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer people. Matabeni’s paper unpacks those contestations within pride in two cities in South Africa, highlighting in particular the ways class, race, space and gender disrupt LGBTQ identifications, organizing and terms of belonging. Using the frame of ihlazo, a notion that includes, inter alia, shame, embarrassment and disgrace, the paper exposes the racial and class collisions that compromise gay and lesbian groups in post-apartheid South Africa.

The segregated space of the city of Cape Town also forms the backdrop of Joanna Wheeler’s paper Troubling Transformation: Storytelling and political subjectivities in Cape Town, South Africa. Wheeler’s paper starts from the assumption that everyday experiences of marginalization and violence are difficult to access and articulate, and yet have significant weight in shaping relationships of power, access, and rights. How to understand this dimension of the lived realities of marginalization is an epistemological challenge. In response to that challenge, Wheeler’s paper analyses engaged story-based methods with people from informal settlements and townships in Cape Town. It traces the articulation of the stories and explores how people’s political subjectivities are constituted within this process. By considering the epistemological and heuristic dimensions of a storytelling approach, the article explores how deep gaps and brutal silences that characterize life on the margins in Cape Town can be made into voices that resonate and can be heard.

We round up this collection of articles with a contribution by Encarnación Gutiérrez Rodríguez which reflects on those subject positions that do not have gathered enough resonance to break silences, make noise and gain a voice. Political Subjectivity, Transversal Mourning and a Caring Common: Responding to Deaths in the Mediterranean focuses on the question of why mass deaths in the Mediterranean have not caused the kind of public outcry in Western Europe that the terror attacks did in Paris in 2015. This article thereby expands the regional scope of our special issue beyond Africa and the African diaspora to address important questions of legal and affective postcolonial entanglements in contemporary worlds. Following Judith Butler’s question on whose lives are not publicly mourned and Édouard Glissant’s critique on the ‘duality of self-perception’, Gutiérrez Rodríguez proposes transversal mourning as a point of departure from which to think of anti-racist political subjectivities which strive for a caring common and transformative justice. In a way, transversal mourning, like storytelling, becomes an act of witnessing which enables new forms of solidarity in the future.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a final note on the initial workshop setting and broader framework is in order. Current demands to decolonize the university do not only concern demographic, institutional or representational matters, but they also challenge modes of academic knowledge production in profound ways. Therefore, we are not only concerned with the question of how to address classificatory violence without reproducing it, but also with the means of expression, dissemination and attachment that shape our matters of concern. During our gathering in Stellenbosch we were wary not to produce an academic echo chamber, set in the serene enclosure of the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study, where we would only speak to ourselves. We therefore tried to disrupt the classical workshop format by allowing different forms of engagement and conversation, including the collaboration with Open Forum and a number of discussions with student and community activists. To us, the workshop marked a point of diffraction (Haraway Citation1988), from which new lines of thought and new creative forms could potentially emanate. This special issue is one of them. The performances that emerged through Open Forum and resulted in the travelling exhibition Phefumla! – Breathe! were another. We have included images of some of the art works at the end of this introduction as a way of continuing our conversation (). We also hope that the articles will resonate widely and thus be provocative in their own right.

Acknowledgements

The workshop, which was mainly held at StIAS (the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study) and supported by the Point Sud Programme of the German Research Foundation, was co-convened by Katharina Schramm and Lindsey Reynolds. Special thanks go to Marco Scholze of Point Sud for his support, in particular for making it possible to divert some of the funding to the Open Forum initiative. We thank the University of Amsterdam for enabling open access publication of this introduction. The ideas that are presented in this special issue form part of a longstanding conversation between Katharina Schramm and Kristine Krause about the matter of political subjectivity in our respective research fields and between Greer Valley and Katharina Schramm on forms of collaboration in activist and academic fields. We would like to thank Lindsey Reynolds as well as all the other participants of the workshop who are not represented here: Kwesi Aikins, Naluwembe Binaisa, Giorgio Brocco, Adam Haupt, Chris Lee, Zine Magubane, Amade M’charek, Nolwazi Mkhwanazi, Rob Pattman, Suren Pillay, Charles Piot and Noah Tamarkin. They all enriched our discussion tremendously. We would also like to thank the students and artists of Open Forum for sensitizing us to other modes of expression through poetry, performance and visual arts. Nadine Cloete as well as Ledelle Moe were great interlocutors and supporters. Bongani Mgijima, the director of the Stellenbosch Museum, offered us his space and a glimpse of his remarkably irrepressible spirit. We also thank Lucy Campbell of Transcending History Tours for teaching us on the resonances of slavery and indigenous presence in the city space of Cape Town. Iain Harris from Coffeebeans Routes walked us through Stellenbosch and Kayamandi. Mandy Sanger and the District Six Museum gave us insights into the more recent reverberations of apartheid segregation and forced removals. Thanks go also to the activists of the Delft Safety Group who shared their experiences with us. Our colleague Elaine Salo had enthusiastically accepted the invitation to join our discussions. However, she could no more deliver her paper ‘When my shit IS your shit – Race, rights, recognition and the poo wars in neoliberal Cape Town 2010–2014’. Elaine died just a few weeks before our workshop took place. We dedicate this special issue to her.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Katharina Schramm http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9275-6387

Kristine Krause http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1339-0450

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It should be noted that the museum’s director, Bongani Mgijima, was very supportive of the Open Forum initiative. See the museum website for further detail, available on http://www0.sun.ac.za/museum/html/ (last downloaded 13 September 2018).

2 Apartheid prime ministers D.F. Malan and Hendrik Verwoerd were university alumni. The anthropologist and linguist Max Eiselen, who was the architect of the infamous Bantu Education Act, also worked and taught here.

3 For students’ accounts of discrimination at Stellenbosch, see the documentary film Luister/Listen, available on https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sF3rTBQTQk4 (last downloaded, 13 September 2018).

References

- Ahmed, Sara. 2004. “Affective Economies.” Social Text 22 (2): 117–139. doi: 10.1215/01642472-22-2_79-117

- Arendt, Hannah. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. Orlando: Harcourt.

- Booysen, Susan, and Gillian Godsell, eds. 2017. Fees Must Fall: Student Revolt, Decolonization and Governance in South Africa. Johannesburg: Wits University Press.

- Bowker, Geoffrey C., and Susan Leigh Star. 2000. Sorting Things Out: Classification and Its Consequences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Brown, Julian. 2015. South Africa’s Insurgent Citizens: On Dissent and the Possibility of Politics. Auckland Park: Jacana.

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, Thinking Gender. New York: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 2006. Precarious Life: The Power of Mourning and Violence. New York: Verso Books.

- Butler, Judith. 2015. Notes Toward a Performative Theory of Assembly. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Davison, Patricia. 1990. “Rethinking the Practice of Ethnography and Cultural History in South African Museums.” African Studies 49 (1): 149–167. doi: 10.1080/00020189008707721

- Dubow, Saul. 1995. Scientific Racism in Modern South Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frazer, Nancy. 2005. “Reframing Justice in a Globalizing World.” New Left Review 36: 69–88.

- Frazer, Nancy. 2010. “Injustice at Intersecting Scales: On ‘Social Exclusion’ and the ‘Global Poor’.” European Journal of Social Theory 13 (3): 363–371. doi: 10.1177/1368431010371758

- Hacking, Ian. 1986. “Making up People.” In Reconstructing Individualism: Autonomy, Individuality, and The Self in Western Thought, edited by Thomas C. Heller, and Christine Brooke-Rose, 222–236. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Hall, Stuart. 2000. “Who Needs Identity?” In Identity Reader, edited by P. du Gay, J. Evans, and P. Redman, 15–30. London: Sage.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi: 10.2307/3178066

- Isin, Engin F. 2009. “Citizenship in Flux: The Figure of the Activist Citizen.” Subjectivity 29: 367–388. doi: 10.1057/sub.2009.25

- Isin, Engin F. 2012. “Enacting Citizenship.” In Citizens Without Frontiers, 108–146. London: Bloomsbury.

- Isin, Engin F. and Greg Marc Nielsen. 2008. Acts of Citizenship. London: Zed Books.

- Krause, Kristine, and Katharina Schramm. 2011. “Thinking Through Political Subjectivity.” African Diaspora 4 (2): 115–134. doi: 10.1163/187254611X607741

- Kristeva, Julia. 1982. Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Merry, Sally Engle. 2006. “Transnational Human Rights and Local Activism: Mapping the Middle.” American Anthropologist 108 (1): 38–51. doi: 10.1525/aa.2006.108.1.38

- Rancière, Jacques. 2004. “Who is the Subject of the Rights of Man?” South Atlantic Quarterly 103 (2): 297–310. doi: 10.1215/00382876-103-2-3-297

- Robins, Steven. 2014. “The 2011 Toilet Wars in South Africa: Justice and Transition Between the Exceptional and the Everyday After Apartheid.” Development and Change 45 (3): 479–501. doi: 10.1111/dech.12091

- Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 2001. “The Anthropology of the State in the age of Globalization.” Current Anthropology 42 (1): 125–138.

- Von Schnitzler, Antina. 2016. Democracy’s Infrastructure: Techno-Politics and Citizenship After Apartheid. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi: 10.1080/00313220600769331