Abstract

Objective: The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of self-assessed preoperative physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking with self-assessed quality of life, negative intrusive thoughts and depressed mood after radical prostatectomy.

Materials and methods: The Laparoscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open (LAPPRO) trial was a prospective, controlled, non-randomized longitudinal trial of patients (n = 4003) undergoing radical prostatectomy at 14 centers in Sweden. Validated patient questionnaires were collected at baseline, and 3, 12 and 24 months after surgery.

Results: Preoperative medium or high physical activity or low alcohol consumption or non-smoking was associated with a lower risk of depressed mood. High alcohol consumption was associated with increased risk of negative intrusive thoughts. Postoperatively, quality of life and negative intrusive thoughts improved gradually in all groups. Depressed mood appeared to be relatively unaffected.

Conclusions: Evaluation of preoperative physical activity, tobacco and alcohol consumption habits can be used to identify patients with a depressed mood in need of psychological support before and immediately after surgery. Quality of life and intrusive thoughts improved postoperatively.

Introduction

Localized prostate cancer that is not deemed suitable for active surveillance is treated with surgery or radiation, both of which are associated with complications and treatment-related morbidity [Citation1,Citation2]. The Laparoscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open (LAPPRO) trial, which included more than 4000 patients operated on by experienced surgeons, was recently reported on. It shows that 20% of patients self-reported urinary incontinence 12 months after radical prostatectomy and two-thirds of patients reported erectile dysfunction [Citation1]. In a substudy of LAPPRO, a significant proportion of the men reported having negative intrusive thoughts about the cancer before surgery, which was associated with impaired self-assessed quality of life postoperatively [Citation3].

There is growing interest in the influence of preoperative factors on postoperative recovery and quality of life. Abstaining from alcohol and smoking has been associated with reduced postoperative morbidity and complications [Citation4,Citation5]. Physical activity and prehabilitation have been found to enhance recovery in various aspects such as shorter hospital stay and reduced complication rates after certain types of surgery [Citation6,Citation7].

In two observational studies, one on breast and the other on colorectal cancer, a higher preoperative level of physical activity was associated with faster physical recovery as reported by the patients 3 weeks after surgery [Citation8,Citation9]. In a previously published study of patients in the LAPPRO trial, it was found that a high level of physical activity preoperatively was associated with reduced need for sick leave after radical prostatectomy compared to men with lower physical activity [Citation10]. Preoperative physical activity has also been associated with improved quality of life after radical prostatectomy [Citation11].

The aim of this study was to evaluate the association of self-assessed preoperative physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking with the postoperative progress of self-assessed quality of life, negative intrusive thoughts and depressed mood after radical prostatectomy.

Materials and methods

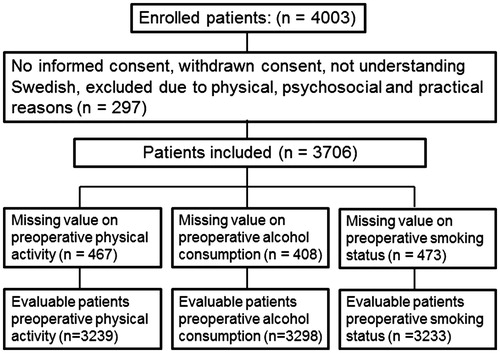

Laparoscopic Prostatectomy Robot Open (LAPPRO) is an open, controlled and non-randomized prospective longitudinal trial comparing open retropubic and robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer at 14 centers in Sweden, as previously described in detail [Citation12] (trial registration number: ISRCTN06393679). The primary endpoint was urinary incontinence 1 year after surgery, as previously reported [Citation1]. Self-assessed physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, quality of life, negative intrusive thoughts and depressed mood, as well as functional outcomes and symptoms, were explored in extensive questionnaires preoperatively and 3, 12 and 24 months after surgery. The questionnaires were based on concepts introduced in previous research projects [Citation13,Citation14]. The questionnaires were validated face-to-face with prostate cancer patients (an investigator accompanied them while completing the questionnaire and assessed their understanding of the items), content validated by experts in the field of urology and tested in a pilot study of 100 men with subsequent revisions, as described by Thorsteinsdottir et al. [Citation12]. In total, 4003 patients were included in LAPPRO from 1 September 2008 to 7 November 2011. Exclusion criteria were no or withdrawn informed consent or other reasons (n = 297), which resulted in 3706 evaluable patients ().

Preoperative habits

Participants were asked to estimate their level of physical activity by answering the question: ‘How often have you been physically active for 30 minutes or more with for example bicycling, walking, gymnastics, or similar, in the past month?‘, with the answering categories: 1 ‘Never’, 2 ‘Sometimes (1–2 times/week)‘, 3 ‘Often (3–4 times/week)‘, and 4 ‘Daily or almost daily (5–7 times/week)‘. The answering categories were classified as ‘no or low activity’ (categories 1 and 2) and ‘medium and high activity’ (categories 3 and 4), where the latter category corresponds to fulfilling the national and international criteria for recommended levels of regular physical activity, known to be associated with health benefits [Citation15].

Alcohol consumption was assessed with a modified version of the AUDIT-C scale [Citation16] developed by Steineck [Citation17] and Omerov [Citation18]: 1. ‘Have you been drinking alcohol in the past month?‘, with answering categories ranging from 1 ‘No’ to 5 ‘Yes, every day’; 2. ‘How many drinks have you had on average per week in the past month?‘, with answering categories ranging from 1 ‘Not applicable. I don’t drink alcohol’ to 6 ‘16 or more’; and 3. ‘Have you had six or more drinks on one occasion in the past month?‘, with answering categories ranging from 1 ‘No’ to 5 ‘Yes, every day’.

Consumption was classified as either low or high based on the sum of scores from the three items. High consumption was defined as a total score of at least four points, corresponding to daily drinking or at least 11 drinks per week or binge drinking.

Patients were classified as current smokers (including pipe smoking) or non-smokers (former smokers or never smokers) according to their answer to the question ‘Do you smoke or have you smoked?‘

Outcome measures

Self-assessed quality of life was measured by: ‘How would you describe your quality of life during the past month?’, with response according to a visual analogue scale (VAS) anchored by 0 meaning ‘No quality of life’ and 6 ‘Best possible quality of life’. The answering categories were dichotomized with a cut-off point between 4 (0–4: low/moderate) and 5 (5–6: good/very good), where the former indicates an impaired quality of life [Citation3].

Negative intrusive thoughts were addressed by ‘How often during the past month have you had negative thoughts about your prostate cancer, suddenly and unintentionally?’ The response categories were: 1 ‘Never’, 2 ‘More seldom than once a week’, 3 ‘At least once a week’, 4 ‘At least three times a week’, 5 ‘At least once a day’, 6 ‘At least three times a day’ and 7 ‘At least seven times a day’. Answers were dichotomized as less than once per week (categories 1 and 2) and at least once per week (categories 3–7), according to an earlier study [Citation3].

Self-assessed depressed mood was addressed by the question ‘Would you call yourself depressed?’, with answering categories 1 ‘Yes’ and 2 ‘No’. A similar item, ‘Are you depressed?’ has previously been shown to identify patients who are not depressed [Citation19].

Statistical analysis

A statistical analysis plan was detailed before the analysis. Group sizes in LAPPRO were set to evaluate urinary incontinence [Citation1,Citation12] and were judged to be sufficient to assess the current aim.

In the analyses of the association between preoperative habits and postoperative outcomes, the longitudinal structure was accounted for by a generalized linear repeated measures model with binomial distribution, identity link and robust variance pseudo-likelihood estimation [Citation20]. Interaction effects between the different habits were accounted for in the models.

The three preoperative habits and follow-up time (3, 12 and 24 months) were simultaneously included as fixed effects. To account for interaction effects between time and between the different habits, first, second and third order interactions were added to the model. Among some common covariance structures for the repeated measures, compound symmetry was chosen as it minimized the Akaike information criteria. For depressed mood, the statistical model did not converge when all three variables was included simultaneously. Convergence was met when physical activity and alcohol consumption was included simultaneously in one model and smoking alone in another model.

Results were presented as estimated risks of low/moderate quality of life, intrusive thoughts at least once a week and depressed mood, respectively, and differences between habits in change from preoperatively to 3,12 and 24 months postoperatively with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). No imputation technique was used for handling missing data. The GLIMMIX procedure in SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute), and R version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used.

Results

For the 3706 eligible patients, the response rates for questions on physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking were 3239 (87%), 3298 (89%) and 3233 (87%), respectively (). Response rate for questions related to the outcomes ranged from 87% to 96%.

Patient characteristics and demography

Patient characteristics and demographics are reported in . The median age was 63 years. Sixty-four per cent had American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification category I and 75% were operated on by robot-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy. Among the patients responding to the preoperative questionnaire, 63% were physically active, 87% reported low alcohol consumption and 90% were non-smokers. The prevalence of high alcohol consumption was similar across the levels of physical activity. Smoking was more common among patients reporting no or low physical activity (14%) compared to among medium or highly physically active patients (7%). Thirty-eight per cent had a university education and 91% were married or had a partner.

Table 1. Patient characteristics and demographics.

Self-assessed quality of life

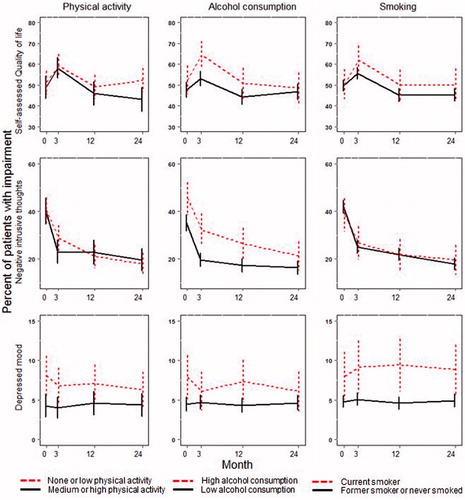

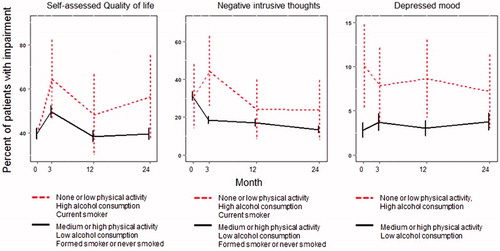

Patients had similar risk of impaired quality of life preoperatively regardless of preoperative habits. In all groups, increased impaired quality of life was found 3 months after the operation, which improved over time (). Patients being physically inactive, having high alcohol consumption and being smokers had a 23% increase in risk at 3 months. The corresponding increase for patients being physically active, having low alcohol consumption and not smoking was 10% (). The differences between habits regarding change from baseline were not statistically significant ().

Figure 2. Risk (%) of impairmenta with 95% confidence intervals preoperatively and 3, 12 and 24 months postoperatively. aLow/moderate quality of life, intrusive thoughts at least once a week and depressed mood, respectively.

Figure 3. Risk (%) of impairmenta with 95% confidence intervals preoperatively and 3, 12 and 24 months postoperatively. aLow/moderate quality of life, intrusive thoughts at least once a week and depressed mood, respectively.

Table 2. Change in risk (95% confidence interval) of impairmentTable Footnotea from preoperatively to 3, 12 and 24 months postoperatively.

Negative intrusive thoughts

Patients reporting low alcohol consumption had a lower risk of negative intrusive thoughts preoperatively compared with patients reporting high alcohol consumption. In all groups, the impairment improved over time. Patients who were physically active, had low alcohol consumption and were non-smokers had an 18% reduction in the risk of negative intrusive thoughts at 24 months compared to baseline (). The differences between habits regarding change from baseline were not statistically significant.

Self-assessed depressed mood

Patients who reported medium or high physical activity or low alcohol consumption or not smoking had a lower risk of self-reported depressed mood preoperatively compared with patients who reported no or low physical activity or high alcohol consumption or current smoking. The differences in risk were not statistically significant. Depressed mood was relatively unaffected over time.

Discussion

Among patients undergoing prostatectomy, preoperative physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking were related to depressed mood. Postoperatively, quality of life and negative intrusive thoughts improved gradually in all groups. Depressed mood appeared to be relatively unaffected. Three months after the operation, a decline in quality of life was seen in all groups, followed by a later improvement. Patients who were physically active or had low alcohol consumption or were former or never smokers were associated with a lower risk of self-assessed depressed mood. Depressed mood was relatively unaffected over time. There appeared to be interaction effects between physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking, as patients reporting themselves as being physically active, having low alcohol consumption and being non-smokers experienced lower risks of impaired quality of life, negative intrusive thoughts about the prostate cancer and depressed mood compared with patients who were physically inactive, had high alcohol consumption and were current smokers.

In a previous report [Citation3], a statistically significant association between negative intrusive thoughts at least once a week and impaired quality of life, feeling depressed during the past month and waking up with worry or anxiety more than once per week were found. This psychological distress was reported both preoperatively and postoperatively in a subgroup of the trial [Citation3]. Furthermore, preoperative physical activity has been associated with improved quality of life after radical prostatectomy in other studies [Citation11].

Longitudinal change in health-related quality of life has been studied in randomized trials of patients with colorectal cancer, with the aim of evaluating laparoscopic and open surgical technique. These patients also have an initial postoperative decline and subsequent improvement of quality of life. Janson et al. found that Swedish patients with colon cancer were, in all aspects, worse off immediately after surgery, but at 12 weeks were doing better than they had been preoperatively [Citation21]. In another study of patients with rectal cancer, health-related quality of life was considerably impaired during the first 6 months after the operation, followed by improvement until 2 years [Citation22]. As surgeries may differ in regard to the extent of the procedure, patients also differ in the magnitude of the postoperative decline in quality of life and when the subsequent improvement occurs.

A study of prostate cancer in Sweden [Citation23] found an increased risk of suicide following a prostate cancer diagnosis. The risk was the highest during the first 6 months after diagnosis, followed by a gradual decline. The risk among men diagnosed with a locally advanced or metastatic prostate cancer was twice the rate in the general Swedish population [Citation24], and Fang et al. [Citation25] found an increased risk of suicide in men with prostate cancer during the first year. This indicates the importance of viewing the cancer diagnosis as a trauma, and the need to study factors that can be modified by interventions in order to decrease trauma-related symptoms and decrease the risk of suicide.

Strengths of this study include a large study cohort, the multicenter and prospective longitudinal design, and high compliance in answering the questionnaires. The questionnaires included questions used before [Citation17] and were content and face-to-face validated. This study analyzed all included patients, not only patients operated on by surgeons with experience of more than 100 procedures, as in the report on the primary endpoint of urinary incontinence [Citation1].

Limitations include the non-randomized design. Ten per cent reported being current smokers, which is similar to the average rate of 9% in Sweden [Citation26], and 13% reported high alcohol consumption, which is similar to the observed general Swedish male population [Citation27]. Another limitation is that the study design does not permit assessment of the causal pathway between physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking, and psychological distress.

In conclusion, the evaluation of preoperative physical activity, tobacco and alcohol consumption habits can be used to identify patients in need of psychological support before and immediately after surgery.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participants in the LAPPRO trial, the members of the steering committee, the investigators at the participating hospitals, and the personnel at the trial secretariat for their provision of study material and administrative support.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Haglind E, Carlsson S, Stranne J, et al. Urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction after robotic versus open radical prostatectomy: a prospective, controlled, nonrandomised trial. Eur Urol. 2015;68:216–225.

- van Stam MA, Aaronson NK, Pos FJ, et al. The effect of salvage radiotherapy and its timing on the health-related quality of life of prostate cancer patients. Eur Urol. 2016;70:751–757.

- Thorsteinsdottir T, Hedelin M, Stranne J, et al. Intrusive thoughts and quality of life among men with prostate cancer before and three months after surgery. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:154.

- Eliasen M, Gronkjaer M, Skov-Ettrup LS, et al. Preoperative alcohol consumption and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;258:930–942.

- Thomsen T, Villebro N, Moller AM. Interventions for preoperative smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3:CD002294.

- Santa Mina D, Clarke H, Ritvo P, et al. Effect of total-body prehabilitation on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2014;100:196–207.

- Singh F, Newton RU, Galvao DA, et al. A systematic review of pre-surgical exercise intervention studies with cancer patients. Surg Oncol. 2013;22:92–104.

- Nilsson H, Angeras U, Bock D, et al. Is preoperative physical activity related to post-surgery recovery? A cohort study of patients with breast cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e007997.

- Onerup A, Bock D, Borjesson M, et al. Is preoperative physical activity related to post-surgery recovery?: a cohort study of colorectal cancer patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2016;31:1131–1140.

- Angenete E, Angeras U, Borjesson M, et al. Physical activity before radical prostatectomy reduces sick leave after surgery: results from a prospective, non-randomized controlled clinical trial (LAPPRO). BMC Urol. 2016;16:50.

- Santa Mina D, Guglietti CL, Alibhai SM, et al. The effect of meeting physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors on quality of life following radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:190–198.

- Thorsteinsdottir T, Stranne J, Carlsson S, et al. LAPPRO: a prospective multicentre comparative study of robot-assisted laparoscopic and retropubic radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2011;45:102–112.

- Johansson E, Steineck G, Holmberg L, SPCG-4 Investigators, et al. Long-term quality-of-life outcomes after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting: the Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group-4 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:891–899.

- Steineck G, Bergmark K, Henningsohn L, et al. Symptom documentation in cancer survivors as a basis for therapy modifications. Acta Oncol. 2002;41:244–252.

- Haskell WL, Blair SN, Hill JO. Physical activity: health outcomes and importance for public health policy. Prev Med. 2009;49:280–282.

- Bush K, Kivlahan D, McDonell M, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med. 1998;16:1789–1795.

- Steineck G, Helgesen F, Adolfsson J, Scandinavian Prostatic Cancer Group Study Number 4, et al. Quality of life after radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:790–796.

- Omerov P, Steineck G, Runeson B, et al. Preparatory studies to a population-based survey of suicide-bereaved parents in Sweden. Crisis. 2013;34:200–210.

- Skoogh J, Ylitalo N, Larsson Omerov P, Swedish-Norwegian Testicular Cancer Group, et al. ‘A no means no’–measuring depression using a single-item question versus Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-D). Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1905–1909.

- Agresti A. Foundations of linear and generalized linear models. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2015.

- Janson M, Lindholm E, Anderberg B, et al. Randomized trial of health-related quality of life after open and laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:747–753.

- Andersson J, Angenete E, Gellerstedt M, et al. Health-related quality of life after laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer in a randomized trial. Br J Surg. 2013;100:941–949.

- Carlsson S, Sandin F, Fall K, et al. Risk of suicide in men with low-risk prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1588–1599.

- Bill-Axelson A, Garmo H, Lambe M, et al. Suicide risk in men with prostate-specific antigen-detected early prostate cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study from PCBaSe Sweden. Eur Urol. 2010;57:390–395.

- Fang F, Keating NL, Mucci LA, et al. Immediate risk of suicide and cardiovascular death after a prostate cancer diagnosis: cohort study in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:307–314.

- OECD. Health at a glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

- Kallmen H, Wennberg P, Ramstedt M, et al. Changes in alcohol consumption between 2009 and 2014 assessed with the AUDIT. Scand J Public Health. 2015;43:381–384.