Abstract

Objective: This retrospective, single-centre, non-interventional, registry-based study evaluated patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) treated with enzalutamide in daily clinical practice at Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden.

Materials and methods: Registry data were reviewed for patients treated with enzalutamide pre- or post-chemotherapy initiated between December 2013 and June 2017. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS) in post-chemotherapy patients. Secondary endpoints were enzalutamide treatment duration in the pre- and post-chemotherapy setting. This study was approved by the Lund regional Ethics Review Board (Dnr:2017/716) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03328364).

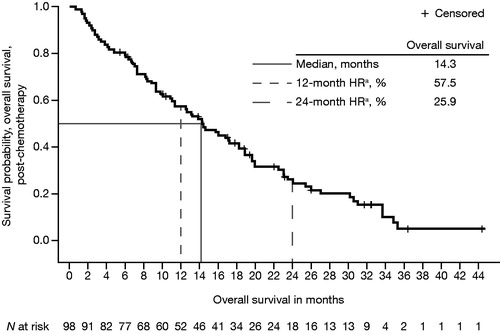

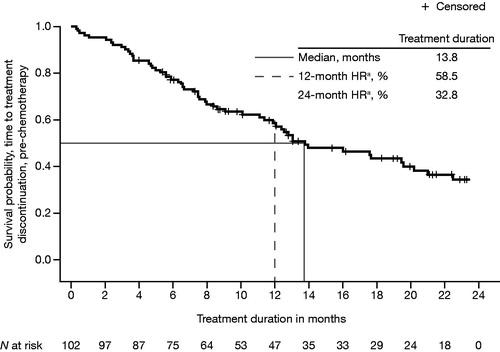

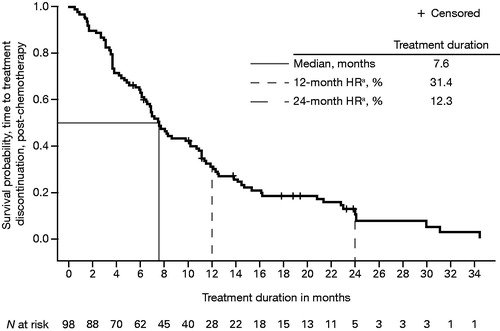

Results: A total of 102 pre-chemotherapy and 98 post-chemotherapy patients were included. Median age was higher in the pre- than in the post-chemotherapy group (77 vs 72 years, respectively). Median OS in post-chemotherapy patients from initiation of enzalutamide until death from any cause was 14.3 months [95% confidence interval (CI) = 11.00–18.20]. Median treatment duration was 13.8 months (95% CI = 11.4–20.2) and 7.6 months (95% CI = 6.3–10.2) for pre- and post-chemotherapy patients, respectively.

Conclusion: Enzalutamide can be used to effectively treat mCRPC patients in daily clinical settings, despite the patients being older and less healthy than those enrolled in the previous randomised, clinical registration studies.

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer among men in Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Iceland), with ∼24,000 diagnoses each year (equivalent to an age-standardised incidence of 92.7 per 100,000 men) and 5500 deaths attributable to the disease [Citation1]. Medical or surgical castration is a widely accepted treatment for advanced prostate cancer [Citation2]; however, a majority of patients who die from prostate cancer have made a transition to the castration-resistant prostate cancer stage [Citation3]. Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) is the most advanced form of prostate cancer, and most prostate cancer deaths come from this disease segment. For many years, chemotherapy with docetaxel was the only available treatment for patients with mCRPC. In 2013, the European Medicines Agency approved enzalutamide (Xtandi®; Astellas Pharma Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for the treatment of adult men with mCRPC whose disease has progressed on or after docetaxel therapy, as well as for adult men with mCRPC in whom chemotherapy is not clinically indicated. Enzalutamide is also indicated for the treatment of adult men with high-risk non-metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer [Citation4].

Enzalutamide has demonstrated superiority over placebo regarding overall survival (OS) and radiographic progression-free survival in two multinational, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 studies [Citation4–6]. In the AFFIRM pivotal trial, men with mCRPC (n = 1199) and an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status score ≤2 received enzalutamide or placebo following prior chemotherapy and were followed for a median of 14.4 months [Citation5]. Similarly, in the PREVAIL pivotal trial, men with mCRPC (n = 1717) and ECOG ≤1 who had not received prior chemotherapy received enzalutamide or placebo and were followed for a median of 22 months [Citation6].

Although randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have strong internal validity that minimises bias, they apply strict inclusion and exclusion criteria that can lead to a relatively homogenous patient population. As a result, RCT evidence may not be generalisable to daily clinical practice. To supplement the evidence framework for a drug’s external validity, it is also important to evaluate local treatment patterns and patient characteristics and outcomes. Registry-based analyses are recognised as important sources of real-world evidence because they provide prospective data on treatment received (i.e. medical visits, laboratory monitoring and criteria for drug stopping or adjustment) among patients with diverse characteristics, and reflect local and national clinical guidelines [Citation7,Citation8]. Recommendations for the timing of drug initiation are similar, regardless of whether the setting is clinical practice or clinical research [Citation9]; however, treatment duration might differ in the real world, as patients are likely to be older and/or less healthy than those eligible for RCT inclusion [Citation7,Citation10].

This registry-based analysis evaluated patients with mCRPC treated with enzalutamide at a university hospital in the southernmost province of Sweden.

Materials and methods

Setting

A retrospective, single-centre, non-interventional, registry-based study was conducted at Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden. Since 2012, this hospital has maintained a follow-up registry of all patients with mCRPC treated with newer agents, including enzalutamide. Skåne University Hospital was one of the first hospitals in Sweden to initiate treatment with enzalutamide and, at the time of study initiation, had the longest national follow-up of patients receiving enzalutamide. Prior to initiation, the study was approved by the regional Ethics Review Board in Lund (Dnr:2017/716) and the regional healthcare council. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03328364).

Patients

Patients at Skåne University Hospital with mCRPC were considered eligible for analysis if they met all of the following criteria: (i) ≥18 years of age; (ii) treated with enzalutamide and ongoing androgen deprivation therapy with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GNRH) analogue or orchiectomy (surgical or medical castration); and (iii) were initiated on treatment any time between 1 December 2013 and 30 June 2017. Patients were excluded based on previous exposure to the following: (i) radium-223; (ii) abiraterone acetate; and/or (iii) cabazitaxel for mCRPC. Additionally, patients previously exposed to chemotherapy or abiraterone acetate plus prednisolone in combination with a GNRH analogue for metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer were excluded.

The full analysis set included two patient groups: those treated with enzalutamide either after (post-chemotherapy) or before (pre-chemotherapy) chemotherapy treatment. Treatment of post-chemotherapy mCRPC patients with enzalutamide commenced in December 2013 [Citation4], and treatment of pre-chemotherapy patients started in July 2015 following reimbursement in Sweden for that indication [Citation11]. Patients were followed until 30 November 2017. A separate analysis of a third patient group treated with enzalutamide following prior treatment with KEES (Ketokonazole, Etoposide, Estramustine, Sendoxan) was conducted, but is not discussed in this manuscript, as KEES is not a standard treatment in Sweden (for baseline characteristic data, see Supplementary Table S1). KEES is an oral metronomic chemo-hormonal combination regimen developed to reduce the toxicity associated with composite chemotherapy regimens [Citation12].

Study design

The purpose of this study was to provide outcomes data from daily clinical practice in Sweden among patients with mCRPC using enzalutamide. The primary endpoint was OS, defined as the time from treatment initiation to death by any cause, in patients with mCRPC treated with enzalutamide who had previously undergone treatment with chemotherapy (post-chemotherapy patients). Secondary endpoints were duration of treatment with enzalutamide, defined as the time from treatment initiation to discontinuation for any cause, in both pre- and post-chemotherapy patients. We also compared results observed in daily clinical practice with those reported in the PREVAIL (pre-chemotherapy) and AFFIRM (post-chemotherapy) phase 3 RCTs of enzalutamide [Citation5,Citation6].

In the registry, several baseline patient- and disease-specific variables, as well as disease severity measures, were captured for all patients, including: ECOG performance scores, Gleason score, and baseline data on plasma prostate-specific antigen (PSA). These variables were also measured in the enzalutamide RCTs [Citation5,Citation6].

Statistical analyses

This was a descriptive study and did not include an a priori hypothesis or any power calculations. Information was obtained from the registry database. To ensure quality, the sponsor assigned an external monitor from LINK Medical Research Sweden to compare the registry data to the patient’s medical chart for the primary and secondary objectives. Collected data were anonymised and included patient demographics and drug administration information. Descriptive statistics were used for continuous variables, including patient number, median, interquartile range, overall range, minimum and maximum. Frequencies and percentages were used for categorical data, and percentages were based on the total number of patients, with missing data included in calculations. Median OS, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), was estimated using Kaplan–Meier survival curves, as was median treatment duration. Treatment duration for missing enzalutamide stop dates was replaced with OS duration, and all treatments longer than 700 days were re-checked.

Results

The initial data set comprised 211 patients; two were excluded (one patient did not receive the study drug, and one had an identical treatment start/end date) and nine were treated with KEES. The final analysis set for the primary endpoint (OS) and secondary endpoints (treatment duration pre- and post-chemotherapy) included 200 study registry patients treated with enzalutamide: 102 patients were treated pre-chemotherapy and 98 were treated post-chemotherapy. Within the registry population, median patient age was higher in the pre-chemotherapy (77 years; range = 56–95) than in the post-chemotherapy patient group (72 years; range = 46–84) ().

Table 1. Key differences in patient characteristics at baseline in the registry study conducted at Skåne University Hospital and randomised clinical trials of enzalutamide in patients with mCRPC [Citation5,Citation6,Citation14,Citation15].

Gleason scores in registry patients were similar, and baseline ECOG performance status was generally comparable between the pre- and post-chemotherapy groups. The majority of patients had ECOG performance scores of 0 or 1; however, 15% and 13% of pre- and post-chemotherapy registry patients, respectively, had a baseline ECOG performance score ≥2. Plasma PSA levels upon initiation of enzalutamide varied substantially in both registry patient groups, with a median of 53 ng/mL (range = 2.4–4822) in the pre-chemotherapy group and a post-chemotherapy median of 91.5 ng/mL (range = 0.5–5000).

Compared with the phase 3 enzalutamide RCT patients, the registry patient population was generally older. Median age was 72 vs 69 years for enzalutamide patients in the post-chemotherapy registry vs clinical trial and 77 vs 72 years in the pre-chemotherapy registry vs clinical trial, respectively [Citation5,Citation6]. Additionally, compared with RCT patients, a higher proportion of registry patients had ECOG scores ≥2 [Citation5,Citation6].

Key efficacy outcomes are summarised in , along with comparative results from the phase 3 enzalutamide clinical trials. Median OS from enzalutamide initiation until death from any cause in post-chemotherapy registry patients was 14.3 months (95% CI = 11.00–18.20) (). This was shorter than the median OS observed in the enzalutamide clinical trial of post-chemotherapy patients [Citation5]. Median treatment duration was 13.8 months (95% CI = 11.4–20.2) in registry patients receiving enzalutamide pre-chemotherapy () and 7.6 months (95% CI = 6.3–10.2) in registry patients receiving enzalutamide post-chemotherapy (). Clinical trial patients also had a longer mean treatment duration (16.6 and 8.3 months, respectively, for pre-chemotherapy and post-chemotherapy patients) than registry patients [Citation5,Citation6].

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier plot of overall median survival from enzalutamide initiation to death from any cause in post-chemotherapy patients with mCRPC and prior docetaxel treatment. HR: hazard ratio; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. aHR from time-to-event analysis.

Figure 2. Kaplan–Meier plot of median treatment duration, from enzalutamide initiation to all-cause treatment discontinuation in pre-chemotherapy patients with mCRPC. HR: hazard ratio; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. aHR from time-to-event analysis.

Figure 3. Kaplan–Meier plot of median treatment duration, from enzalutamide initiation to all-cause treatment discontinuation in post-chemotherapy patients with mCRPC. HR: hazard ratio; mCRPC: metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. aHR from time-to-event analysis.

At the time of analysis, 20% of the registry study post-chemotherapy patients were still alive, and fewer post-chemotherapy patients remained on treatment with enzalutamide compared to those treated before chemotherapy (12% vs 45%).

Discussion

This retrospective, registry-based study evaluated nearly 4 years of clinical use and outcomes in patients with mCRPC treated with enzalutamide between December 2013 and November 2017. To our knowledge, this is the first analysis to report on OS and treatment duration with enzalutamide in a day-to-day clinical setting. To date, it is also the longest reported prospective follow-up of enzalutamide in patients with mCRPC.

The median OS for the 98 post-chemotherapy registry patients was 14.3 months; ∼4.1 months shorter than the OS observed in the AFFIRM pivotal study (18.4 months). Post-chemotherapy registry patients also had about a 1-month shorter treatment duration with enzalutamide than RCT patients (7.6 vs 8.3 months) [Citation5]. Additionally, the 102 pre-chemotherapy registry patients had a median treatment duration of 13.8 months, which is shorter than the median treatment duration observed in the PREVAIL pivotal study (16.6 months) [Citation6]. Despite these important distinctions in OS and treatment duration, the difference in median post-chemotherapy treatment duration for registry compared to RCT patients was only 0.7 months [Citation5].

These observed variations in treatment and outcomes between registry and RCT patients may be explained by comparing the respective populations. Specifically, baseline patient characteristics, inclusion criteria, and key aspects of study design (e.g. criteria for stopping treatment) differed substantially between the RCTs and daily clinical practice. The current analysis was limited to a single urban centre in a Nordic country, while the enzalutamide RCTs were multinational and enrolled geographically diverse populations. Compared to AFFIRM and PREVAIL, the registry patients were older in both the post-chemotherapy (72 vs 69 years in AFFIRM) and pre-chemotherapy (77 vs 72 years in PREVAIL) groups [Citation5,Citation6]. The younger age seen in the phase 3 data can be explained by selection bias in clinical trials, which typically enrol younger and healthier patients [Citation13]. Additionally, a recently published national study confirms that the older age seen in our patient registry is representative; 75% of Swedish patients with prostate cancer filling their first prescription for novel antiandrogens (enzalutamide and abiraterone acetate) are ≥70 years of age (median = 75 years) [Citation3].

At baseline, registry patients also reported poorer overall ECOG performance scores than participants in the phase 3 trials. A meaningful sub-set of registry patients (13–15%) had moderate-to-severely impaired ambulation and daily functioning (based on ECOG scoring ≥2). Patients with an ECOG performance status >2 were excluded from AFFIRM, and only 8.8% of AFFIRM enzalutamide patients had an ECOG performance score of 2 [Citation5]. The PREVAIL analysis excluded patients with ECOG performance scores >1 [Citation6]. Registry patients also had a high rate of prevalent cardiovascular disease, at 33% and 40% in the post- and pre-chemotherapy groups, whereas the RCTs excluded patients with clinically significant cardiovascular disease [Citation14,Citation15].

It is, therefore, reasonable to infer that the moderate discrepancies observed between the current registry cohort and clinical trial outcomes reflect the older age and/or compromised physical status of registry patients at baseline. It is also important to note that, in this analysis, the decision to stop treatment was reached at the physician’s discretion for reasons that could include non-response, severe adverse events, patient-reported quality-of-life or patient choice (see Supplementary Tables S2–S4). In contrast, in both phase 3 studies, criteria for stopping were pre-specified, with treatment continued until radiographic disease progression was confirmed or there was evidence of skeletal related events; study protocols also allowed treatment discontinuation for safety, non-compliance, or other reasons [Citation5,Citation6]. Therefore, in a real-world setting, where disease progression criteria are broader, patients are more likely to be seen as progressed, and treatment discontinuation may occur more rapidly.

At the time of analysis, OS data for pre-chemotherapy patients treated with enzalutamide were not yet mature. This was also not an endpoint in the study protocol. Approximately 45% of registry patients were still receiving treatment at the time of the treatment duration analysis. OS for pre-chemotherapy patients will be investigated and presented in a future report.

There was no possibility to verify the reported reasons for stopping enzalutamide and/or cause of death; this was also not the purpose of the registry study. Since these data were anonymous and aggregated, it is difficult to draw further conclusions. See Supplementary Tables S2–S4 for information regarding reasons for patient discontinuation and Supplementary Table S5 for patient death.

Several strengths and limitations of the current study should be noted. Data were collected at a single site selected for its extensive, longstanding and comprehensive patient registry. Skåne University Hospital is an experienced and active clinical trial centre and was one of the first sites in Sweden to adopt enzalutamide treatment following its approval. It is the third-largest hospital in Sweden, with a catchment area of ∼1.7 million patients in Southern Sweden, including Lund and Malmö [Citation16]. Each year, ∼1200 individuals in the County Council of Skåne are diagnosed with prostate cancer [Citation17], representing a sizeable fraction (10–13%) of the roughly 10,000 annual diagnoses in Sweden [Citation1].

Since publicly financed healthcare systems, patient demographics and use of the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines are similar for all Nordic countries, the current results may be relevant for patients across the Nordic region. However, other regional factors, such as prescribing patterns and recommendations regarding the use of novel drugs in mCRPC, may vary and could limit study generalisability. These data are also likely not applicable beyond the Nordic region due to differences in patient populations, healthcare systems and treatment patterns. Also, as with any registry-based study, these results are fully dependent on the quality and completeness of the registration data [Citation7].

Lastly, results of this registry-based study were interpreted alongside those from two pivotal trials. Any cross-study comparisons between this registry-based study, which is reflective of daily clinical practice, and data obtained from the two pivotal studies of enzalutamide should be interpreted with caution due to differences in study design, populations and statistical analysis. Across all analyses, however Kaplan–Meier curves were used to estimate median OS, which facilitated the direct observation of results across studies [Citation5,Citation6].

It is important to note that, in 2013, enzalutamide was a new treatment option for patients with mCRPC. There were no specific recommendations regarding when to stop treatment other than those stipulated in the pivotal studies. Subsequently, EAU treatment guidelines and the Swedish national guidelines for treatment of prostate cancer have evolved to provide more specific stopping criteria for patients receiving enzalutamide and/or abiraterone acetate. Specifically, European treatment guidelines from 2016 [Citation2] and Swedish guidance from 2017 [Citation18] recommend that treatment be terminated if two of three disease criteria are fulfilled: (i) clinical progression; (ii) biochemical progression or (iii) radiological progression.

In conclusion, this study reported on the real-world use of, and treatment outcomes with, enzalutamide in pre- and post-chemotherapy patients with mCRPC. Data were obtained from a single-site registry in Sweden. This analysis demonstrates that enzalutamide can be used effectively to treat mCRPC patients in clinical settings. Patients in this study were more elderly and less healthy than patients enrolled in the enzalutamide randomised clinical trial program; despite this, enzalutamide has shown clinical benefit in terms of OS in our Swedish population-based cohort after prior chemotherapy, as anticipated, with a shorter drug exposure.

Alghazali_et_al_supplemental_appendix.docx

Download MS Word (42.1 KB)Acknowledgements

Medical writing support was provided by Cricket Darby, PhD, and Caitlin Rothermel, MPH, of BioScript, and editorial support was provided by Beatrice Vetter-Ceriotti and Lauren Smith from Complete HealthVizion, funded by the study sponsors.

Disclosure statement

Mohammed Alghazali has received personal fees from Astellas Pharma a/s during the conduct of the study. Annica Löfgren was a study coordinator in a study funded by Astellas Pharma a/s. Leif Jørgensen is an employee at IQVIA Solutions a/s and reports receiving grants from Astellas Pharma a/s during the conduct of this study. Maja Svensson is an employee at Astellas Pharma a/s. Karin Fagerlund is an employee at Astellas Pharma a/s and the medical adviser/study lead for this study. Anders Bjartell has received funding from Astellas Pharma a/s.

Data availability

Access to anonymised individual participant-level data will not be provided for this trial, as it meets one or more of the exceptions described on www.clinicalstudydatarequest.com under ‘Sponsor Specific Details for Astellas’. The ethical approval limits the access to data.

Additional information

Funding

References

- NORDCAN [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): Association of the Nordic Cancer Registries; c2009. Data from the online tool in the NORDCAN database containing prevalence data [updated 2018 June 28; cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: http://www-dep.iarc.fr/nordcan/english/frame.asp.

- Cornford P, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, et al. EAU-ESTRO-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II: treatment of relapsing, metastatic, and castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2017;71:630–642.

- Franck Lissbrant I, Ventimiglia E, Robinson D, et al. Nationwide population-based study on the use of novel antiandrogens in men with prostate cancer in Sweden. Scand J Urol. 2018;52:143–150.

- eMC [Internet]. Surrey (United Kingdom): Datapharm Ltd; c2019. Xtandi 40mg soft capsules; [updated 2018 Oct 30; cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3203/smpc.

- Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1187–1197.

- Beer TM, Armstrong AJ, Rathkopf DE, et al. Enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer before chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:424–433.

- Garrison LP Jr., Neumann PJ, Erickson P, et al. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: the ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health. 2007;10:326–335.

- Blommestein HM, Franken MG, Uyl-de Groot CA. A practical guide for using registry data to inform decisions about the cost effectiveness of new cancer drugs: lessons learned from the PHAROS registry. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33:551–560.

- Mottet N, Bellmunt J, Briers E, et al. EAU - ESTRO - ESUR - SIOG Guidelines on prostate cancer [Internet]. The Netherlands: European Association of Urology; [cited 2018 Jun]. Available from: http://uroweb.org/guideline/prostate-cancer/.

- Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, et al. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1763–1774.

- The Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency [Internet]. Stockholm (Sweden): Tandvårds- och läkemedelsförmånsverket; Xtandi ingår i högkostnadsskyddet [Xtandi is included in the high-cost protection]; [cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.tlv.se/beslut/beslut-lakemedel/generell-subvention/arkiv/2015-06-15-xtandi-ingar-i-hogkostnadsskyddet.html.

- Jellvert A, Lissbrant IF, Edgren M, et al. Effective oral combination metronomic chemotherapy with low toxicity for the management of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2011;2:579–584.

- Booth CM, Tannock IF. Randomised controlled trials and population-based observational research: partners in the evolution of medical evidence. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:551–555.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. A safety and efficacy study of oral MDV3100 in chemotherapy-naive patients with progressive metastatic prostate cancer (PREVAIL); [cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01212991.

- ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Safety and efficacy study of MDV3100 in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer who have been previously treated with docetaxel-based chemotherapy (AFFIRM); [cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01212991.

- Handbook for visiting students [Internet]. Lund (Sweden): Lund University; 2016. [cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://issuu.com/medfak-lu/docs/handbook_for_visiting_students_issu.

- Region Skåne [Internet]. Kristianstad (Sweden): Region Skåne; c2018. Positiv utveckling för prostatapatienter [Positive development for prostate patients]; [cited 2019 Jul 10]. Available from: https://www.skane.se/organisation-politik/Nyheter/Halsa-och-vard/2017/positiv-utveckling-for-prostatapatienter/.

- Uppsala: Regionala Cancercentrum I Samverkan; Nationellt vårdprogram för prostatacancer [Internet]. Prostatacancer: Nationellt vårdprogram [Prostate Cancer: National Care Program]: version 1.2. Available from: https://www.cancercentrum.se/samverkan/cancerdiagnoser/prostata/vardprogram/.