Abstract

Objectives

To determine the rate of incisional hernia after surgery for renal cell carcinoma, to compare the rate after open vs minimally invasive surgery and radical nephrectomy vs partial nephrectomy and to identify risk factors for incisional hernia.

Materials and methods

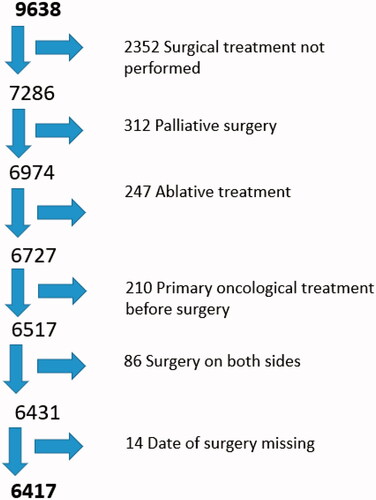

From the Renal Cell Cancer Database Sweden we identified all patients (n = 9,638) diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma in Sweden between January 2005 and November 2015. Of these, 6,417 were included in the analyses to determine comorbidity and subsequent diagnosis of or surgery for incisional hernia.

Results

In all, 6,417 patients underwent surgery for renal cell carcinoma between January 2005 and November 2015, of these 5,216 (81%) underwent open surgery and 1,201 (19%) underwent minimally invasive surgery. Altogether 140 patients were diagnosed with incisional hernia. The cumulative rate of incisional hernia after 5 years was 5.2% (95% confidence interval [CI] = 4.0–6.4%) after open surgery and 2.4% (95% CI = 1.0–3.4%) after minimally invasive surgery (p < 0.05). In Cox proportional hazard analysis, age and left-sided surgery were associated with incisional hernia in the open surgery group (both p < 0.05), whereas in the minimally invasive group, no statistically significant risk factors for incisional hernia were found.

Conclusions

Open surgery for renal cell carcinoma is associated with a significantly higher risk for developing incisional hernia. If open surgery is the only option, care should be taken when choosing the approach and closing the wound. More studies are needed to find strategies to reduce the risk of abdominal wall complications following open kidney surgery.

Introduction

Incisional hernia is a well-known complication after abdominal cavity surgery. Incisional hernia is not only a potentially life-threatening condition, but it is also a costly burden to society since most patients need surgical repair and the recurrence rate is high [Citation1].

Studies on the rate of incisional hernia after surgery on the intestine, liver, pancreas, etc. have found rates to be as high as 20% after open surgery [Citation2]. Less is known about the rate of incisional hernia after surgery for renal cell carcinoma. A small Swedish study [Citation3] reported the incisional hernia rate to be 5%, and a recently published review article [Citation4] suggested it to be as high as 15%.

Around 1,300 cases of renal cell carcinoma are diagnosed, and around 500 patients die of renal cell carcinoma in Sweden each year [Citation5]. About 65% of renal cell carcinoma cases are diagnosed in men. The incidence of renal cell carcinoma increased over several years in both men and women until a few years ago, when it formed a plateau of 1,300 new renal cell carcinoma cases per year [Citation5]. The increase in rate of renal cell carcinoma has partly been due to an aging population and partly due to the more widespread use of tomographic imaging where renal cell carcinomas are detected incidentally.

The tumor is localized in 85% of cases and treatment is aimed at removal of the tumor. Localized renal cell carcinomas are usually removed by radical nephrectomy or by nephron-sparing techniques such as partial nephrectomy or, in frail persons, thermal ablation. Surgery can be performed openly or by minimally invasive techniques such as laparoscopic, robot-assisted laparoscopic or hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery, as well as thermal ablation. Ablation of the tumor is carried out by heating or freezing the targeted area.

Guidelines from the European Association of Urology (EAU) as well as the American Urological Association (AUA) recommend partial nephrectomy for T1 and T2 tumors whenever possible [Citation6,Citation7], since the oncological outcome is the same. According to Swedish guidelines, at least 50% of all T2 tumors should undergo surgery with minimally invasive partial nephrectomy [Citation8]. The combination of these recommendations, development of techniques and the ambition to spare nephrons have led to an increase in the number of partial nephrectomies in Sweden over the last 10 years.

Surgery on the kidney may be performed via an extraperitoneal or a transabdominal approach with either open or minimally invasive techniques. Open extraperitoneal surgery on the kidney is usually approached via a flank incision between the 11th and 12th ribs or just below the 12th rib, effectively exposing the targeted organ. With the open transabdominal approach, an oblique subcostal incision is used to reach the kidney. A disadvantage of these incisions is the trauma inflicted on the sensory and motor nerves in the area, which can lead to pain, paresthesia and muscle weakness below the incision, resulting in bulging [Citation3,Citation9,Citation10]. Bulging after open renal surgery should not be mistaken for incisional hernia.

Muscle weakness makes repair of incisional hernia in the flank more complicated due to a less stable aponeurosis for anchoring the mesh and closer proximity to the bony structures. These factors make flank incisional hernia repair much more demanding than midline incisional hernia repair [Citation4,Citation11]. Consensus has yet to be reached regarding the optimal closure technique for flank incisions [Citation12], despite the morbidity associated with flank incisional hernia and the complexity of repair.

The aim of this study was to determine the rate of incisional hernia after surgery for renal cell carcinoma and to compare the rate after open vs minimally invasive surgery with radical or partial nephrectomy, respectively, and risk factors for developing incisional hernia.

Materials and methods

As a primary source of data, we used the Renal Cell Cancer Database Sweden (RCCBaSE) [Citation13], which in turn is based on the National Swedish Kidney Cancer Register (NSKCR), where all diagnosed renal cell carcinomas in Sweden are recorded as well as treatment and tumor characteristics. NSKCR is linked with several other nationwide epidemiological databases and registers. The National Patient Register (NPR), which includes statistics on surgical diseases and treatments, was used to find comorbidity diagnoses and the diagnosis/treatment of incisional hernia using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). These data are registered at the outpatient visit prior to surgery and at the time of discharge. Finally, the Swedish Cause-of-Death Register (CDR) was used to record death as a censoring event.

Cohort

The cohort included all patients in Sweden diagnosed with renal cell carcinoma between November 2005 and March 2015 (n = 9,638).

Cases excluded: no surgical treatment performed (n = 2,352); palliative surgery (n = 312); oncological treatment prior to surgery (n = 210); and bilateral surgery (n = 86). Ablative treatments such as thermal ablation (n = 247) and cases where date of renal surgery was missing (n = 14) were also excluded.

Outcome and predictors

The primary outcome was diagnosis and/or surgical treatment for incisional hernia registered in NPR after surgical treatment for renal cell carcinoma. A diagnosis of incisional hernia was defined as ICD codes K43.0–K43.2, K43.6–K43.7 or K43.9 recorded at discharge or subsequent outpatient visit. Surgery for incisional hernia was defined as intervention codes JAD10–JAD87.

Predictors of interest were open surgery or laparoscopic surgery. Radical or partial nephrectomy, tumor stage, affected side, gender, age, transperitoneal or extraperitoneal approach and year of surgery were covariates.

Statistical analysis

Time-to-event analysis was used to determine the impact of surgical approach on the risk for incisional hernia, using the date of surgery as the time of inclusion in the cohort. Death and loss to follow-up were treated as censored events. The cohort was followed until November 2015. The cumulative rate was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Diagnosis and/or surgery for incision was used as the endpoint. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard regression analyses were performed to analyze risk factors.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Review Board in Stockholm (ref 2017/1211-31/2).

Results

Baseline data are presented in . The final cohort comprised 4,002 men and 2,415 women (62% vs 37%). There was no age difference between men (median 66.0 years ± 11.36) and women (68.0 years ± 11.32). Stage T1 was most common in both open and minimally invasive groups (49% vs 78%), whereas more advanced stages (T3 and T4) had open surgery to a greater extent (90%). The transabdominal approach was used in 85% of cases.

Table 1. Baseline data among patients treated with surgery for renal cell carcinoma either with open or minimally invasive surgical technique that have been diagnosed or treated for incisional hernia in Sweden, 2005–2015.

A total of 6,417 patients underwent surgery for renal cell carcinoma during the study period. Of those, 5,216 (81%) underwent open surgery and 1,201 (19%) minimally invasive surgery. By the end of the study, 140 patients had been diagnosed with incisional hernia. The majority (n = 124, 89%) occurred in the open surgery group.

The cumulative rate of incisional hernia at 5 years was for the total cohort 4.5% (95% CI = 3.6–5.4%) and after minimally invasive and open surgery 2.4% (95% CI = 1.0–3.4%) and 5.2% (95% CI = 4.0–6.4%), respectively.

Univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses are presented in . We adjusted for radical or partial nephrectomy, tumor stage, affected side, gender, age, surgical approach and surgical technique.

Table 2. Multivariable Cox proportional hazard analyses with diagnosis and/or surgery for incisional hernia as the endpoint among patients treated with surgery for renal cell carcinoma either with open or minimally invasive surgical technique in Sweden, 2005–2015.

There was a significant association between surgical approach (open vs minimally invasive) with a HR = 1.74 (95% CI = 1.02–2.98) and risk for developing incisional hernia, but not with any of the other covariates.

In the open surgery group univariate analyses showed an association of increased risk for incisional hernia for surgery performed on the left side, HR = 1.46 (95% CI = 1.02–2.09) and age above 55 years (p-value = 0.04).

In the minimally invasive group, no covariate was associated with incisional hernia.

Discussion

In this population-based study, the risk for developing incisional hernia after surgery for renal cell carcinoma was low (cumulative rate = 4.5% after 5 years). The risk after open surgery, however, was 1.74- (95% CI = 1.02–2.98) times greater than after minimally invasive surgery.

Flank incision is believed to decrease the risk for incisional hernia, but a recently published review article [Citation4] showed an event rate of 15% (including both incisional hernia and other defects such as bulging) after flank incision for open kidney surgery was reported.

Incisional hernias are usually a consequence of poor surgical technique and, though studies on how to prevent incisional hernia after a flank incision are scarce, the most important measure to prevent incisional hernia is believed to be meticulous closing technique. The same closure technique as recommended for midline incisions, i.e. small bites and close stitches [Citation14,Citation15], should be used for flank incisions [Citation4,Citation12]. Other recommendation on how to minimize the risk for incisional hernia after flank incision are: (1) close the flank in two layers, maintaining the anatomical layers and minimizing the risk for motor denervation; (2) limit the vertical position and posterolateral elongation of the incision to limit the number of dermatomes incised; and (3) keep the incision well below the 12th rib to avoid the intercostal nerve between the 11th and 12th ribs [Citation4,Citation12]. There is, however, no large randomized study on location and closure of flank incisions. Further research is needed, especially since the recommendation today is to avoid midline incisions if possible, in order to reduce the rate of incisional hernia [Citation12,Citation16].

Even though the incidence of incisional hernia in the minimally invasive group was even lower (CI after 5 years = 2.4%), the risk factors for incisional hernia development after laparoscopic treatment should be recognized. In a review article from 2010, the rate of trocar site hernia was reported to be 0.5%, ranging from 0–5% [Citation17]. As for surgical technique, the most important measure to prevent incisional hernia is the technique for entering the abdominal cavity and closure of the incision, and for trocar site hernia the size and location of the trocar. Trocar site hernia is more common with increasing port size, particularly if the port site is used for specimen extraction. In the case of renal cell carcinoma, this only applies to small T1 kidney masses. Previous studies have shown the importance of closing trocar site incisions over 10 mm to prevent trocar site hernia [Citation17], as stated in the European Hernia Society guidelines [Citation12]. A recent literature review, including trocar site incisions between 5 and 10 mm, concluded that there is no difference in trocar site hernia rates between sites left open or closed [Citation18].

In the present study, information on the anatomical localization of the incisional hernia was not available. Therefore, it is not known whether the incisional hernia was at a port site (trocar site hernia) or the extraction site in the minimally invasive group. When extracting the specimen through the abdominal wall, it is important to make the incision large enough for the specimen to pass through without stretching the hole in the abdominal wall, which could lead to micro-tears in the aponeurosis. Such tears may not be visible to the eye and therefore not appropriately sutured when closing the wound. Since the rate of incisional hernia is lower with flank incisions than with midline incisions [Citation19,Citation20], it could be advantageous to use one of the lateral port sites for specimen extraction [Citation4] and even for elongation when extracting a larger specimen, even though closure is easier using a midline port. There may be more advantages using a Pfannenstiel incision for specimen extraction rather than elongating a port site incision [Citation16], not only lowering the risk for incisional hernia but also reducing hospital stay and the amount of postoperative analgesia.

The main risk factor for incisional hernia is surgical technique when closing the incision [Citation4,Citation12], as discussed above. However, patient-related factors also play a role. In this study, age was a significant risk factor in the open surgery group (p-value = 0.04). In elderly patients it may therefore be wise to choose a minimally invasive technique instead of an open. If partial nephrectomy is not feasible laparoscopically, then laparoscopic radical nephrectomy could be chosen instead of open surgery partial nephrectomy as long as the contralateral kidney and renal function are normal.

Also, in the open group, left-sided incisions were significantly more prone to incisional hernia (p-value = 0.04). This has previously been shown in studies on abdominal aortic surgery and colon surgery. Similar reports have been reported for bulging [Citation9] after surgery for renal cell carcinoma. This is believed to be the result of the kidney’s anatomy since it is situated more superiorly in the abdominal cavity. This leads to posterolateral elongation and a steeper vertical incision, resulting in more trauma to the nerves and muscles [Citation4].

If an extraperitoneal approach is used, a flank incision is preferred to save costal nerves, thereby lowering the risk for incisional hernia. In this study no such effect was seen, even though 15% in the open surgery group underwent extraperitoneal surgery.

There may have been a detection bias since the risk of being diagnosed with an incisional hernia could depend on the intensity of postoperative monitoring and imaging diagnostics. As follow-up routines depend on age and tumor stage, this could have resulted in an uneven detection rate.

There are some limitations to this study. One major drawback is that it is a retrospective register-based study with no information about surgical technique regarding whether hand assisted laparoscopic technique was used, incision site, extraction site, closure technique and site of incisional hernia. Furthermore, patients presenting with bulging and not an actual incisional hernia may have been wrongly diagnosed and registered as an incisional hernia. No information about the surgical volumes of the surgeons performing surgery was registered, and lesser experience is a known risk factor for incisional hernia development. There may also have been patients with an incisional hernia where the decision not to perform surgery was made and the ICD-code for incisional hernia never registered.

A strength of this study is the fact that data were obtained from a large population-based cohort with sample size sufficient to identify most important risk factors and that by using several linked registers a follow-up of up to 9 years was achieved.

Conclusion

The risk for incisional hernia after surgery for renal cell carcinoma is low when compared to other procedures in the abdominal cavity. A significant difference in incisional hernia rate between open and minimally invasive surgical techniques was seen, in favor of the latter. In the open surgery group, left-sided incision was found to be a risk factor for incisional hernia development, as was age above 55 years (p-value < 0.05). Avoidance of open surgery may reduce the risk.

The trend towards minimally invasive renal cell carcinoma surgery will probably lead to a lower rate of incisional hernia in the future. However, open surgery will still be required, so knowledge of risk factors for incisional hernia after renal cell carcinoma surgery and how to prevent incisional hernia will continue to be of great importance in the future.

Ethic approval

This research was performed after approval of the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2017/1211-21/2).

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have a conflict of interest in this research.

References

- Poulose BK, Shelton J, Phillips S, et al. Epidemiology and cost of ventral hernia repair: making the case for hernia research. Hernia. 2012;16(2):179–183.

- Patel SV, Paskar DD, Nelson RL, et al. Closure methods for laparotomy incisions for preventing incisional hernias and other wound complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD005661.

- Inkiläinen A, Styrke J, Ljungberg B, et al. Occurrence of abdominal bulging and hernia after open partial nephrectomy: a retrospective cohort study. Scand J Urol. 2018;52(1):54–58.

- Zhou DJ, Carlson MA. Incidence, etiology, management, and outcomes of flank hernia: review of published data. Hernia. 2018;22(2):353–361.

- Socialstyrelsen [Internet]. Stockholm (Swe), Cancer statistics Sweden. [cited 2020 Oct 23]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik-och-data/statistik/statistikamnen/cancer/.

- Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol. 2015;67(5):913–924.

- Campbell S, Uzzo RG, Allaf ME, et al. Renal mass and localized renal cancer: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2017; 198(3):520–529.

- Sveriges Kommuner och Regioner [Internet]. Stockholm (Swe), National guidelines Renal Cell Carcinom Sweden. [cited 2020 Oct 2]. Available from: https://kunskapsbanken.cancercentrum.se/diagnoser/njurcancer/vardprogram/.

- Chatterjee S, Nam R, Fleshner N, et al. Permanent flank bulge is a consequence of flank incision for radical nephrectomy in one half of patients. Urol Oncol. 2004;22(1):36–39.

- Crouzet S, Chopra S, Tsai S, et al. Flank muscle volume changes after open and laparoscopic partial nephrectomy. J Endourol. 2014;28(10):1202–1207.

- Kapur SK, Butler CE. Lateral abdominal wall reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2018;32(3):141–146.

- Muysoms FE, Antoniou SA, Bury K, et al. European Hernia Society guidelines on the closure of abdominal wall incisions. Hernia. 2015;19(1):1–24.

- Landberg A, Lindblad P, Harmenberg U, et al. The renal cell cancer database Sweden (RCCBaSe) - a new register-based resource for renal cell carcinoma research. Scand J Urol. 2020;54(3):235–240.

- Deerenberg EB, Harlaar JJ, Steyerberg EW, et al. Small bites versus large bites for closure of abdominal midline incisions (STITCH): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1254–1260.

- Israelsson LA, Millbourn D. Prevention of incisional hernias: how to close a midline incision. Surg Clin N Am. 2013;93(5):1027–1040.

- Tisdale BE, Kapoor A, Hussain A, et al. Intact specimen extraction in laparoscopic nephrectomy procedures: Pfannenstiel versus expanded port site incisions. Urology. 2007;69(2):241–244.

- Helgstrand F, Rosenberg J, Bisgaard T. Trocar site hernia after laparoscopic surgery: a qualitative systematic review. Hernia. 2011;15(2):113–121.

- Gutierrez M, Stuparich M, Behbehani S, et al. Does closure of fascia, type, and location of trocar influence occurrence of port site hernias? A literature review. Surg Endosc. 2020;34(12):5250–5258.

- Lee L, Mata J, Droeser RA, et al. Incisional hernia after midline versus transverse specimen extraction incision: a randomized trial in patients undergoing laparoscopic colectomy. Ann Surg. 2018;268(1):41–47.

- Halm JA, Lip H, Schmitz PI, et al. Incisional hernia after upper abdominal surgery: a randomised controlled trial of midline versus transverse incision. Hernia. 2009;13(3):275–280.