ABSTRACT

Transformative agroecology challenges industrialized food and farming systems, proposing an alternative vision in which farms are designed around ecological symbioses and embedded within socially just food networks. However, at a policy level, alternative conceptualizations of agroecology have emerged that emphasize on-farm efficiency gains but lack broader objectives of agroecosystem and food system transformation. This phenomenological inquiry explores the agroecological narrative among Scottish farmers and considers its impacts on agroecosystem and food system change. Interviews were conducted across 15 farms in Scotland (20 participants) following the trans positional cognition approach (TPCA). Actualizations of agroecology were found to be value-driven approaches to developing individualized, lower-input farming systems. All farms were attempting to influence agroecosystem change through the application of ecological principles, and most (11/15) were contributing to food system change directly through involvement in alternative food networks. Smaller-scale farmers appear to deliver the most authentic actualizations of transformative agroecology but emphasized more strongly their financial challenges. A key recommendation for policymakers is to strengthen the support mechanisms available for small-scale ecological agriculture.

Introduction

The term “agroecological transition” now requires clarification, given the diverging conceptualizations of agroecology that have accompanied its increasing institutional acceptance (Giraldo and Rosset Citation2018). The extent of food and farming change that might be realized depends on whether agroecology more closely aligns with a “conforming” or “transformative” definition (Levidow, Pimbert, and Vanloqueren Citation2014). This dichotomy of interpretations – a top-down set of practices to be integrated into a system that closely resembles business-as-usual, and a food system transformation that fundamentally challenges capitalism – presents a dilemma. The former may provide a gateway to the latter, but it also risks etiolating agroecology to an approach devoid of a social justice objective (Dale Citation2020; Schiller et al. Citation2020).

Several recent studies have highlighted this tension in practice. In Nicaragua, the incorporation of food sovereignty policies had been a step forward for the agroecological movement, but the impact was diluted by the government’s overall hybrid approach that was also supportive of the industrialized food system (Schiller et al. Citation2020). Similarly, Murguia Gonzalez et al. (Citation2020) noted the challenges faced by El Salvador’s agroecological movement: engage with policymakers and exist within the industrial system, or risk the movement’s credibility by not engaging. Demeter, a certification scheme for produce grown on biodynamic farms in 65 different countries, represents one of the success stories of the agroecological movement. However, research in Denmark with Demeter-certified biodynamic farmers highlighted a need to develop agricultural policy that supports a diverse range of farming approaches so that viability is not contingent on agribusiness and other currently dominant food system actors (Aare et al. Citation2021). Agroecology may be increasingly recognized by both farmers and institutions, but there is a challenge in developing suitable policy frameworks that are supportive of the transformative narrative (López-García et al. Citation2020).

Given these diverging conceptualizations of agroecology, we sought to explore how this approach was being implemented at the farm level in Scotland. Farmers cannot take sole responsibility for driving agroecological transition – it requires the engagement of multiple stakeholders in participatory, transdisciplinary processes (Kapgen and Roudart Citation2020; Ollivier et al. Citation2018). Lasting sustainable agricultural interventions require participatory approaches that are recognizing of unique farming contexts (Pretty Citation1994). Nevertheless, farmers can directly influence the agroecosystem and food system change to which transformative agroecology aspires (Gliessman Citation2016) – the former through the implementation of ecological practices, and the latter by integration with alternative food networks. A review of farmers’ adoption of soil health practices highlighted that transformative change was linked to modification of farmers’ mental models, brought about by, for example, financial pressures or poor health, whereas incremental change involved the integration of new practices that fitted with existing conceptualizations of their farms (Carlisle Citation2016). It is not clear, however, whether a greater extent of transformation necessarily follows from such incremental change.

While, theoretically, transition takes place through five distinct levels (Gliessman Citation2016) – efficiency enhancement, substitution of practices, agroecological redesign, establishment of alternative food networks, and global food system redesign – transition in practice is not necessarily linear. Padel, Levidow, and Pearce (Citation2020) found that UK farms in agroecological transition did not progress sequentially through the efficiency, substitution, and redesign phases of transition (Hill and MacRae Citation1996). Instead, farmers had various entry points to transition and followed no common process of redesign. Other studies have highlighted the diverse mechanisms through which farm-level agroecological transitions can progress (Tessier et al. Citation2021; Toffolini et al. Citation2019). With no single starting point or transition pathway, the trajectory and eventual outcomes of transition are unclear without an understanding of farmers’ motivations and objectives.

The objective of the paper is to identify whether farmers in Scotland are aligned to a transformative vision of agroecology that culminates in food system redesign or are only interested in efficiencies offered by changes in their practices. We explore the experiences of farmers actualizing agroecology – individuals that identify with this label and who are putting the approach into practice on their farms. We consider the influence of their approaches on both agroecosystem and food system transformation. In doing so, the research aims to better understand the challenges for transformative agroecology consequent of the currently fragmented discourse (Schiller et al. Citation2020).

Methodology

This study is a phenomenological exploration of the lived experiences of agroecological farmers in Scotland. Phenomenology was chosen over other qualitative research approaches because the purpose of the study is to understand the way in which agroecology, an emerging approach in the chosen case study area, was actualized by a limited group of farmers. The study is therefore not attempting to build a theory of agroecological farming, rather, it explores the experiences of self-identified agroecological farmers, and considers the implications of their approaches for agricultural transformation (Creswell and Creswell Citation2013; Smith and Shinebourne Citation2012). Theoretically, agroecology is well-defined, but there is a need to better understand how conceptualizations of this approach are shaping agriculture in practice.

Phenomenological inquiries aim to distil phenomena of interest into their essences, or key characteristics. Descriptive phenomenology posits that essences can be described objectively (Giorgi and Giorgi Citation2003), whereas interpretivist phenomenology views essences and the subjectivity through which they arise as inseparable (Olekanma, Dörfler, and Shafti Citation2022; Shinebourne Citation2011). This study positions phenomenology within the interpretivist research paradigm (Dörfler and Stierand Citation2020) and favors the trans positional cognition approach (TPCA) (Olekanma, Dörfler, and Shafti Citation2022), which integrates the descriptive and interpretivist traditions of phenomenology by providing a methodological protocol for managing subjectivity. This is accomplished through bracketing, a process by which researchers attempt to suspend their judgments, but also make transparent the values and knowledge that may influence their interpretation of participants’ experiences (Dörfler and Stierand Citation2020).

In exploring actualizations of agroecology, Scottish farming was chosen as a case study. Agricultural land use in Scotland is dominated by rough grazing and grasslands. Of the 5.64 million hectares in agricultural production, 466 000 hectares are used for cereal and oilseed production, 28 300 hectares for potatoes, 21 000 for vegetables, and 2 200 for soft fruit (Scottish Government Citation2020). Scottish farming is at a pivotal moment, with exit from the European Union having triggered a redesign of agricultural policy. Details of the future policy framework are currently unknown, but the Scottish Government has announced an intention to become a leader in sustainable agriculture in response to the climate and biodiversity crises (Scottish Government Citation2022). To this end, two recent reports have considered agroecology in Scotland. Lozada and K (Citation2022) conducted a survey of Scottish farmers and found that 60% of the 192 respondents had integrated at least one agroecological practice into their farm management. However, it is not clear how, or if, integration of these practices translates into more significant transformation at either the agroecosystem or food system level. Further, Cole et al. (Citation2021) identified a need to understand the socioeconomic impacts of farm-level agroecology in Scotland. In considering the impacts of farmers’ actualizations of agroecology on agroecosystem and food system change, this research aims to address this knowledge gap.

Interviews with 20 agroecological farmers across 15 farms in Scotland were conducted (). Farms were of mixed type and size. The interviews were semi-structured and were conducted either in person or remotely over Zoom. Initially, research participants were purposively selected, and subsequent participants were acquired via a snowballing strategy. Participants were required to be farming in Scotland and associate their approach with agroecology. The type or number of practices or principles implemented by farmers did not influence selection – it was only important that they identified their farms as being in some way agroecological. In this way, the interviews could generate insights into the way in which different conceptualizations of agroecology manifest in practice. Interviews sought to understand farmers’ approaches and experiences by exploring their background, motivations, objectives, practices, knowledge, and challenges. In doing so, this research considers the implications of different actualizations of agroecology for agricultural transformation. Ten of the interviews were conducted one-to-one but in five cases, two participants were interviewed jointly. The study included farms of all scales: one mixed farm was over 1000 hectares, while two market gardens were producing on less than a hectare. It was deemed important to also include small-scale food producers in the study, given not only the link between agroecology and small-scale farming, but also its associations with market gardening and permaculture (Ferguson and Lovell Citation2014; Morel and Léger Citation2016).

Table 1. Participant details. All participants were based in Scotland and identified their approaches with agroecology.

Interviews were conducted between October 2021 and February 2022. This research received ethics approval from University of Strathclyde. Participants were provided with a study information sheet and consent form prior to taking part in interviews. Data was collected, analyzed, and interpreted following the 6 stage TPCA methodology outlined byOlekanma, Dörfler, and Shafti (Citation2022). These 6 stages are: 1) data collection, 2) data transcription, 3) text analysis, 4) creation of a data display structure, 5) data validation, and 6) idiographic explanation. Each interview lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours. During interviews, conscious effort was made to suspend judgments that may influence interpretation of participants’ experiences. Bracketing continued through the reviewing of transcripts and identification of participant themes (PTs). Once this had been completed for each participant, the individual themes were grouped across participants, removing repetitions. In this way, the PTs were generated. Consciously attempting to see things from the perspectives of the participants, the PTs were again grouped and interpreted, resulting in the researcher’s interpretation of participant themes (Ri-PTs). From the Ri-PTs, an overarching study essence was derived. The ability to step into the shoes of participants was deemed possible because of the lead author’s experience in farming – he had grown up on an arable farm in Fife, a region in the east of Scotland with some of the country’s most fertile agricultural land (Scottish Government Citation2020), and worked here each harvest throughout school and his undergraduate studies. PTs, Ri-PTs, and the study essence were developed into a thematic map (Braun and Clarke Citation2006), which was sent to participants for validation (10/15 responses).

Findings

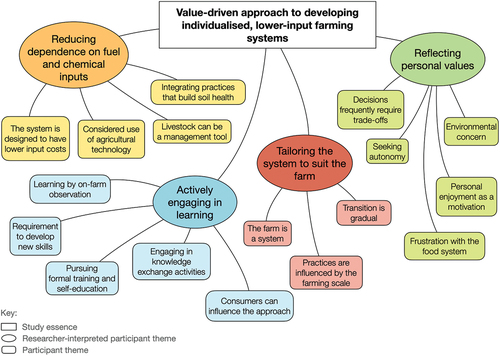

The groups of PTs were interpreted to give four Ri-PTs, illustrated in : reducing dependence on fuel and chemical inputs, actively engaging in learning, tailoring the system to suit the farm, and reflecting personal values. For the actively involved in learning Ri-PT, interpretation was a straightforward process. It was clear that several of the participant themes related to the need to develop new skills and knowledge, and the mechanisms by which farmers could do this. However, the three remaining Ri-PTs were less obvious. For this reason, a discussion between co-researchers to facilitate transpersonal reflexivity is an important step in the TPCA methodology. Initially five Ri-PTs had been identified, but after reflecting on and discussing the assumptions that underpinned the original interpretation of PTs and their groupings, a final group of four Ri-PTs were found to more accurately convey participants’ experiences. These Ri-PTs were interpreted at a higher level of abstraction to give the essence of the considered agroecological actualizations: a value-driven approach to developing individualized, lower-input farming systems. Herein, this section outlines each of the finalized Ri-PTs.

Figure 1. Thematic map developed from interview transcripts. The study ‘essence’ is contained within the rectangular box at the top of the map and is connected to the Ri-PTs in the ovals below, into which feed the PTs. The themes are universal among participants.

Reducing dependence on fuel and chemical inputs

Central to each of the study participants’ farming approaches was the aim of developing lower-input farming systems. Participants were critical of modern agriculture’s high use of fossil fuels and chemicals. This reliance was perceived to be expensive, damaging to the environment, and counter to farmer autonomy. Participants were therefore implementing practices that allowed for reductions in fuel and chemical use.

What I believe is that we can have the whole farm covered in herbal lays, graze the cows in a regenerative way, not plough, not use any chemicals, and try and work a bit more closely with nature.

Farmers need to stop agrochemicals and need to look at their fossil fuel use.

Participants described healthy soils as being vital for the viability of lower-input systems. Several participants (B, C, F and H) stated that their soils were the foundation of their farming approach. Importantly, properly functioning soils were perceived to facilitate a transition away from external inputs.

I expect that the additives we will be using in the future will be more biological and less chemical … but I hope that at some point our soil is working well enough that we don’t have to use them.

In discussing soil health, participants described a farmer-soil relationship based on reciprocity. Participants believed that catering to the needs of their soils would, in turn, allow their soils to help them.

It basically comes down to the soil, looking after the soil, hoping and realising that it can help me grow crops.

Farmers indicated that this was a change from a more conventionally oriented perspective on farming in Scotland, which Participant A described as “extractive.” Participant C, having taken a soil-first approach on his farm for 20 years, spoke of widespread soil degradation on the east coast of Scotland, and noted that his farm had measured increases in soil organic matter during a time when he believed that other local farmers have seen decreases. Participants therefore viewed their approaches as distinct from more conventional farm management, and saw this as influenced by a recent and evolving understanding of the role of soils in healthy agroecosystems. Participants E and H believed that that soil biology deserves greater attention because of these advancements, in addition to the previous doctrine of managing soil chemistry.

Farmers discussed different practices through which they aim to build soil health and so reduce dependence on external inputs. Farmers with an arable enterprise (B, C, E, G and J) were particularly interested in direct or no-till drilling. By disturbing the soil less, these farmers aimed to improve the soil structure and ultimately the quality of their crops. These minimal cultivation practices have lower fuel requirements. Cover cropping was also highlighted as a route to building soil fertility through green manures, and so reducing fertilizer requirements. However, participants G and J described the challenges that Scotland’s temperate presents for the establishment of cover crops in addition to a cash crop in a single growing season. Participants discussed the role livestock could play in building soil health. Several participants (A, B, C and H) were practicing adaptive multi-paddock (AMP) grazing, an approach in which livestock are moved regularly, sometimes multiple times a day. This is a management practice that aims to avoid overgrazing, stimulate grassland productivity, promote biodiversity and build soil fertility. Further, soil health was important to the market gardeners, who discussed observed improvements in the soil after specific practices, namely, incorporating seaweed inputs or local manure, and introducing legumes into the rotation.

While all participants were aiming to integrate practices that reduced input requirements directly or indirectly by building soil health, there was variation in the flexibility with which these practices were implemented. For example, Participant F’s perception of the destructive impacts of plow on the soil meant he was highly critical of this practice. Other farmers were more relaxed about the extent of soil disturbance in their farming systems. For arable farmers, direct drilling systems delivered immediate economic benefits through savings on fuel and labor, but this was only the case if the system did not suffer from a yield reduction. Participant E therefore stated the importance of flexibility in the farming system – sometimes plowing may be the best option, other times it may not. Participant G had only transitioned to a predominantly direct drilling system because he had demonstrated in trials that yields were at least as good as the previous plow-based system. However, there was little motivation for him to further reduce soil disturbance by no-till drilling, perceived to result in a yield reduction, which could not be justified through cost savings or further improvements to soil health. Further, in arable systems, removing the plow presents an additional challenge of weed buildup. Therefore, integrating this practice can require a trade-off – savings on fuel may come with greater dependence on glyphosate for weed control. Participants expressed different views on such dependence on chemicals, with some believing they still had a role to play in farming systems, while others were entirely against their use (Participant O). Participant C, an arable farmer who had been direct drilling for more than 20 years, saw glyphosate-use as only a temporary problem that will eventually be addressed by advancements in knowledge and technology.

Agricultural technology played a role in supporting reduced input farming, but farmers approached this skeptically. Participant A believed that he was less trusting of technological innovations than conventional farmers. Since reducing inputs – including machinery use – was key to the farming system, any technology brought into their operation could not contradict this approach. There was a belief among participants that technologies could be both expensive and potentially damaging to the environment, and so care was required when considering the long-term interests of the farm. Nevertheless, several participants gave examples of ways in which technology was supporting transitions through lower-input systems, namely, sap testing to allow for the precision treatment of crops, and the development of lower carbon fertilizers (Participant J). Technology was therefore generally perceived to have an important role in participants’ farming approaches, but it was considered cautiously.

I’m not totally against technology … It’s about using technology to help you, rather than allowing you to do bad things.

Actively engaged in learning

All the study participants described the learning required for changing their businesses. Participants perceived other farmers as a particularly valuable learning resource. Several farmers (Participants B, C, D, I, and J) highlighted the value of visiting other farms to pick up ideas that might translate into their own farming systems. As well as serving a practical purpose, there was also a social element to these visits – farmers enjoyed catching up with their peers in these settings.

It’s a talking shop. When we get together it’s just … it’s brilliant (Participant C).

In learning from one another, farmers were interested in hearing about different experiences with lower input practices. Participant E emphasized the importance of openness in dialogue with other farmers, and the learning that can be achieved through discussion of failures as well as successes.

I was at a farm tour with them and they were like, “come into this field, it’s a total disaster don’t ever do this”, and that’s the kind of things you need to be able to move forward with an idea.

As well as discussing the integration of specific practices into the farming system, some participants also described how interaction with their peers could help inform the structure of their businesses. As an example, Participant I, market gardeners, were receiving mentoring from a community supported agriculture (CSA) co-operative. Further, Participant D described both receiving and sharing guidance on business diversification in his interactions with neighbors.

I’ve actually helped him go onto a milk vending machine business as well, so it’s worked both ways.

Farmers transitioning their businesses toward direct sales and closer connection with local customers discussed the required broadening of skills. Participants A, F and K spoke of the importance of learning to market their produce. Specifically, Participant K discussed the adverse impact of neglecting marketing on sales, having seen demand for their produce fall after the first COVID-19 lockdown.

I think it’s just relative to last year when people were falling over themselves for vegetables, like this year we haven’t been marketing and we’ve suffered as a consequence of that.

Farmer to farmer knowledge exchange was only one of several learning mechanisms that participants described. Knowledge exchange with universities, research centers, and farming based organizations was also viewed as important for learning. Further, farmers discussed their reading, formal training courses, and a host of free online resources – particularly videos of other farming systems in action. Online material was generally not of other local farming systems, but of farmers around the globe showcasing their systems. Participants A and B described the way in which the principles applied by these farmers, even if farming in very different climactic conditions, were translatable into their own contexts. Observation was also highlighted as a key mechanism for learning at the agroecosystem level, and was described as important for understanding and evaluating the impacts of changes to the farming system. Examples of the role of observation in farming ranged from the more practical and tangible – such as digging holes to evaluate soil health (Participant C), and seeing less flooding in minimally disturbed fields (Participant B) – to the philosophical – several farmers described following nature’s lead. In all cases, farmers used observation as a means of understanding the specific functioning of their own farming systems. Much could be learned from knowledge exchange activities but there remained a need to understand the unique functioning of each farm. Participants engaged in direct sales also described the value of learning from their customers. Participant M highlighted the important role that their customers played in informing the design of their dairy system. Their decision to run a calf at foot dairy was guided by feedback from the public on how they would like the animals to be treated.

Tailoring the system to suit the farm

Participants emphasized that their approaches were tailored to their farms. As opposed to developing their systems from a blueprint, they were designing an approach suited to their own land, climate, and scale. Participants E and J stated their belief that every farm is unique, and the consequent need for flexibility in selecting suitable farming practices. As an example, Participant E believed that because much of her farm was on lighter, sandier soils, AMP grazing would not suit her farming system.

I think every farmer and every farm is different and you’re never going to say, this is the way you should farm one hundred percent, because, you know, everyone’s different.

Further examples of farmers’ tailoring their systems to their environment were provided. Participant A explained that their farm previously had fields in cereal production. This was something they were actively challenging, basing their land use decision on what suits best their Highland environment, as opposed to what had been done previously. Of importance in designing a context-specific farming system was understanding the unique land capabilities of the farm. Participant H explicitly viewed their farm as a system to be kept “in balance” if it was to be sustainable.

Participants also discussed the tailoring of their approaches to their environment with consideration of the rate of farming change. Participants A and B referred to the concept of “maximal sustainable output” (MSO), which they were looking to achieve, albeit cautiously. This is the point at which they could maximize their farm output without having to increase their dependence on external inputs, and is therefore a metric that combines financial and environmental objectives. The participants acknowledged that farming in this way was a process that would take time as they brought about changes to their soils and the wider agroecosystem. Further, Participant E described the gradual process of selectively breeding a herd adapted to her desired grass-based system. The desired results take time, a factor which – if unrecognized – may put farmers off transitions to lower-input systems.

It took 10 years, and people that just say “oh, you know overnight I’ll just turn to grass”. There’ll be a lot of herds that will not fatten on grass, then they’ll suddenly think the system is rubbish.

While participants were tailoring their management to the farm, those farms that were transitioning from conventional systems were designing approaches aligned with their previous capabilities. Learning was key for change, but farmers were not radically overhauling their farm types – dairies remained dairies etc.

We’ve got to do what suits our system … ultimately, we’re growing cereals, so we need to get our wheat in the ground … Wheat’s our cash crop.

The size of the farm also influenced farmers’ practices. Most notably, market gardens operated on very small scales and so relied on manual labor. Several smaller livestock farms (Participants A, F, and H) also primarily relied on manual labor – the daily moves required of AMP grazing could be managed on foot with electric fencing. In contrast, larger scale farms were heavily dependent on mechanization.

Scale seemed to also influence involvement in alternative food networks. While most participants were engaged in direct sales (11/15), it appeared more important for the financial viability of smaller farms. However, this was also clearly influenced by what the farm was producing: arable enterprises producing commodity crops did not lend themselves to selling directly to consumers. Nevertheless, selling directly was clearly more than a factor of scale – it was also a reflection of participants’ personal values and objectives.

Reflecting personal values

Participants discussed concern for the environment, dissatisfaction with the current food system, and the desire to be autonomous. To varying degrees, their farming approaches were a translation of these values into practice. Many of the practices they were implementing were not only justified in terms of their financial benefit, but also in terms of the contributions to their wider value-driven objectives. For example, there appeared to be synergies – win-wins – between some environmental and economic objectives.

It was just to cut costs and to make every enterprise pay. It was only after we kind of started the journey that we were like, ah, there’s actually a million other benefits.

Direct drilling was perceived to have a lower carbon footprint when compared with plow-based systems due to fuel savings and potential benefit from the capacity of the soil to act as a carbon sink (Lal Citation2004), and saved farmers money on fuel and labor. Participant H spoke of the grassland productivity and biodiversity benefits of AMP grazing. Participant A, who was selling directly, discussed how their communication with customers about the way in which they were supporting local ecosystems translated into effective marketing of their produce. In such examples, it appeared that the practices perceived to result in environmental benefits were at least in part enabled by their positive financial outcomes.

Direct sales also facilitated synergies between objectives. Participants expressed frustration with the current food system, and this appeared to be influential in their decisions to sell directly to consumers. In doing so, they were able to retain a greater share of the profits – having cut out supply chain intermediaries – and also contribute to environmental and social goals by supplying their communities with local, sustainably produced food. Direct selling could therefore be an attractive business model, especially for smaller-scale producers, but it was also a means of translating farmers’ values into practice.

Win-wins were of course desirable for all farmers, and Participants A, D, and F discussed a holistic decision-support framework that they used to identify such options. The framework considered the social, environmental, and economic implications of farm management decisions. In general, though, farmers revealed that they were more frequently required to make trade-offs between their objectives than they were able to realize synergies. It appeared that win-wins could carry agroecological approaches so far by, for example, improving the efficiency of the farm. However, for those farms actualizing a more transformative approach, objectives were often in competition. In such cases, the holistic management framework is useful for considering the economic, environmental, and social trade-offs of any decisions.

Some farmers were willing to sacrifice profit for competing objectives, indicating that this approach to farming is not simply about maximizing income. Several examples were given of farmers’ balancing of economic outcomes with environmental goals. Participant A, livestock farmers, discussed limiting stock numbers to increase on-farm species diversity. Participant B, a mixed farmer, described having to trade-off different farm management practices: no-till drilling crops may maintain soil structure, which the farmer associated with positive environmental outcomes, but yields will likely suffer in comparison with a plow-based system. Participant C acknowledged that his sparing use of pesticides and minimal soil disturbance had likely come at the expense of some profit over his career – a trade-off he was happy to make due to his perception that he was building a more resilient farm.

Participants also described the adverse impacts that incorporating social objectives into their businesses could have on profitability. Participant E explained that she passed up an opportunity to increase profits through her farm shop during the COVID-19 lockdown because she was unwilling to sell beef that she perceived as inferior quality or that was produced to lower environmental standards.

I think, possibly if I threw all of my morals out of the window, we could have made quite a lot of money.

Several other farmers discussed the conflict between their social justice and economic objectives. Participant I, market gardeners, described that their priority objective was to pay themselves a fair wage, as their business could not yet support them both fulltime. Despite this, a competing objective of feeding their local communities led them to make decisions that were not profit-maximizing.

Yeah, like micro greens. I mean really, from an economic perspective, we should really do that. But I don’t want to.

Participants A and F were also adamant that their businesses should provide food locally, even if there were opportunities to sell more widely across the UK. As well as providing an income, their produce was a means of building resilience in local communities.

We keep the radius in which we sell beef to as small as possible really.

Market gardeners K, L, and I also emphasized the integral role that engaging with local communities played in motivating their approaches. Participant L stated that the small, intimate, and local nature of his business was a core reason for him enjoying his work so much, and so he had no desire to scale up production.

Therefore, in some instances, the principles and practices of agroecology could be applied by farmers to put the farm on a better financial footing, but in others, they were applied at a financial cost. A temporal dimension is relevant in such decision making, in that decisions that were not profitable in the short-term were perceived in some cases to be an investment in long-term income security – for example, investing in soil health. Nevertheless, it was clear that, for most participants, their actualizations of agroecology were not exclusively economically driven. Farming was a means of translating their personal values into practice, often at the expense of profitability. It was notable that such value-driven decisions were frequently made by smaller-scale producers, who appeared to face the greatest challenges in running profitable businesses. Participant F, farming on approximately 30 hectares, described how his business was not yet able to fully support a couple financially, but this was his aspiration. Participant L, a market gardener, spoke of both the financial hardship in establishing his business, and the additional training he was undergoing as a counselor to diversify his income. Participants A and I both worked part-time elsewhere. These producers were designing approaches that placed the environment and community on at least equal footing with their own profitability.

Discussion

This study has aimed to capture the essence of agroecological farming as actualized in Scotland. In doing so, agroecology was found to be a value-driven approach to developing individualized, lower-input farming systems. This discussion considers the intended impacts of this approach on both agroecosystem and food system transformation.

Participants emphasized the role of ecological principles in shaping the design of their farming systems, and the impacts of these on the agroecosystem varied. The application of ecological principles was contextualized by farmers with reference to soil health: well-managed soil may facilitate productive farming systems with enhanced functional biodiversity and reduced dependence on synthetic inputs (Hawes, Iannetta, and Squire Citation2021). This can improve farm profitability through cost savings. The actualization of such systems was therefore perceived to be predicated on the transformation of soils. However, several of the practices being implemented by farmers for the attainment of this goal also had implications for wider on-farm agroecosystem change. For example, Participants A, H and O, all of whom were livestock farmers, had designed grazing strategies based on grassland rest and recovery. The accompanying result of this was the repopulation of native grassland species and improved on-farm biodiversity. Additionally, cover crops, integrated or trialed by several participants (B, C, E, G, and J), built soil fertility while also providing food and habitat for wildlife. Aiming to realize the soil health benefits of mixed farming systems, Participant E had also integrated sheep into her farming operation. However, emphasis on such ecological practices could align with any agroecological narrative. Rivera-Ferre (Citation2018) found evidence of a more complex discourse than the “conforming” and “transformative” split outlined by Levidow, Pimbert, and Vanloqueren (Citation2014). Five distinct political narratives were identified from an analysis of documents published by organizations and governments around the globe advocating for agroecology: agricultural development; performance; natural resource; climate change and food security; ecosystem’s ecological management; and people’s and women solidarity. Participants were intentionally attempting to bring about agroecosystem change, but the extent of transformation requires consideration also of their wider farming objectives.

Other ecological practices appeared to be less contributory to agroecosystem change. Among arable farmers, direct drilling was widely implemented. For clarity, this is distinct from no-till drilling, which is cultivation-free. Two of the farmers interviewed no-till drilled part of their farm, but explained that this results in a yield reduction. Farmers utilizing direct drilling with a minimum cultivation drill, however, were achieving comparable yields with their previous plow-based systems and benefiting from the cost savings. This practice can benefit soils by maintaining soil structure and preventing erosion consequent of exposed soils. However, farmers direct drilling were still doing so in monoculture systems, the redesign of which could be considered a fundamental aspect of transformative agroecology (Altieri, Nicholls, and Montalba Citation2017). Further, interviews found little evidence to suggest that the monoculture model was being meaningfully challenged. Companion cropping was discussed by Participant J, but this was not at the time a widely integrated practice. Notably, such an objective lacks a clear economic incentive. This contrasts with the outlined soil health building practices, which may result in cost savings on fertilizers, pesticides, chemicals, and labor, and some of which are incentivized through agri-environmental government support schemes.

The extent of agroecosystem redesign therefore appeared to be practice dependent. However, understanding the longer-term impacts of these practices and their implications for agroecosystem change is challenging. It is necessary to understand how such systems are best evaluated, given their complexity (Hawes, Iannetta, and Squire Citation2021). Various approaches have been developed, including whole systems sustainability (Hawes et al. Citation2019), resilience and adaptability (Tittonell Citation2020), and participatory assessments (Dumont, Wartenberg, and Baret Citation2021).

Notably, farmers used terms in addition to agroecological to describe their approaches (). Some of the participants farmed organically and/or identified with the term regenerative agriculture. Two dairy farms labeled their systems specifically as “cow with calf,” as calves spent the first 6 months of their lives with their mothers, in contrast to conventional systems in which cows may be separated from their calves within hours. All three of the market gardeners interviewed also referred to the practices and principles of permaculture, and two were CSA models. One of the benefits of agroecology as a concept appears to be that it brings together other alternative agriculture approaches into a common group. The principles are now well-defined but sufficiently flexible to be implemented at least partially in a range of different farming systems, from larger farms to small scale market gardens.

Agroecosystem redesign is only one objective of transformative agroecology; it also has an integral social dimension (Wezel et al. Citation2020). This is centered on the development of a socially just food system through the provision of healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food. Most of the participants were aiming to directly influence food system change of this kind, primarily by engaging in direct sales. Even those farms not engaged in alternative food networks had a significant social dimension inherent in their approach, through their involvement in knowledge exchange activities. However, an objective of contributing to food system change appeared necessary for more transformative actualizations of agroecology. Participants engaged in direct sales were motivated to feed their local communities, and viewed their produce as high quality and sustainable. Farmers have several sales mechanisms to choose from, including farm shops, online orders, CSA, vending machines, and food hubs. Each participant’s chosen approach was context dependent – there was no standard model by which farms were contributing to the development of alternative food networks. Direct sales facilitated close relationships between farmers and consumers, which was important both in informing the farming approach and in providing farmers with job satisfaction through positive feedback.

A recognized challenge of this approach to food system transformation was the affordability of agroecologically produced food. Participant H aspired to make her produce available to lower income households, but viewed this as a current challenge. Two market gardens had introduced a sliding scale payment mechanism intended to address issues of affordability: individuals who were able to pay above the set price of the vegetable box scheme could do so, with their additional payment subsidizing the price for another customer who otherwise could not afford to sign up to the scheme.

Further, direct selling puts significant demands on the farmer to develop the skills and systems to run their business in this way. Farmers were not only having to learn how to apply ecological principles on their farms, but also how to integrate their businesses within alternative food networks. Their role is no longer limited to food production, but also the marketing and distribution of their produce.

A limitation of this study is that we have explored only the experiences of agroecological farmers, and not a broader range of food system actors that hold influence over agroecological transition in Scotland, including policymakers, agribusiness, retailers, and consumers. While we have demonstrated that, at a farm level, agroecology appears to be conceptualized in a transformative sense in that farmers are aiming at both agroecosystem and wider food system change, this alone is not sufficient to bring about meaningful change. Schiller et al. (Citation2020) outline that in Nicaragua, where an agroecology movement has been developing since the 1980s, present-day food system change is hindered by a lack of government commitment to agroecology. A hybrid approach that aims to support all forms of agriculture undermines the agroecological movement. The Scottish Government, who are in a period of agricultural policy redesign following Brexit, ought to learn from this. Research into agroecological farming was highlighted in their First Steps toward Our National Policy following a 2021 consultation (Scottish Government Citation2021). This may either signal the beginning of institutional adoption or institutional co-optation of agroecology in Scotland, and further research is needed to explore this issue.

The extent of transformation at both an agroecosystem and food system level varied on each farm and was clearly tied to each participant’s need to run a profitable business. The profitability of agroecological systems compared with conventional systems appears to be a complex relationship to unpack and requires consideration of unique farming context. Participants D, E and M described economic pressures that had prompted a shift toward agroecology. Conversely, Participant C, who had been orienting his farm toward agroecology for over 20 years, believed that he had traded profit for farm resilience over the course of his career. Padel, Levidow, and Pearce (Citation2020) identified a number of such “trigger events” that had prompted UK farmers’ agroecological transitions, including financial struggles, farm succession, training events, and concerns over soil fertility.

It was evident that many of the smaller-scale farmers (Participants A, F, I, L, and N) did not generate sufficient income from their farm produce to support them full-time. These farmers had employment elsewhere or had established alternative income streams. For example, Participant A had a part-time research position, Participant N produced an income-generating vlog, and Participant L was training to be a counselor. Importantly, smaller-scale farms of this kind appear to be the most authentic actualizations of agroecology. Transformative agroecology does, after all, place emphasis on small-scale and peasant farming (Giraldo and Rosset Citation2018; Wezel et al. Citation2020). These farms have minimal dependence on fossil fuels, they are circular and diverse, and they support local, rural communities. In contrast, the larger-scale farms were limited in their agroecological actualizations in that they were dependent on the monoculture model, and some were not engaged in alternative food networks. These actualizations are clearly distinct from the transformative agroecological “ideal” described in literature (Dumont, Wartenberg, and Baret Citation2021), defined as the implementation of each of the ecological and socioeconomic principles of agroecology.

Most participants were clear in outlining both environmental and social justice objectives in their farming approach. The extent to which they were able to realize these objectives depended on their unique context or, alternatively stated, their stage of agroecological transition. This suggests that, in the main, farmers’ conceptualizations of agroecology matched a transformative narrative, even if they were unable to bring this vision fully into practice. As such, for the majority of participants, their approach extends beyond an efficiency-driven agroecological narrative by also incorporating objectives relating to food sovereignty through their engagement in short food supply chains (Rivera-Ferre Citation2018). However, two participants did explain that there was no motivation for them to engage in alternative food networks. They expressed values relating to the environment, long-term condition of the farm, and were primarily aiming for a shift to more efficient systems with lower dependence on external inputs.

There may be questions surrounding the capacity of small-scale producers to play a leading role in Scotland’s agricultural transition. However, this study did find an example of a more scalable approach to transformation. Participant D, a dairy farmer, established a co-operative with neighboring dairy farmers that produce their milk to the same environmental standards. Participant D processes the milk of each of the co-operative members at his dairy and, as well as selling directly to the public, has been awarded a contract to supply the local council and school with milk. Co-operatives may therefore be an important mechanism that enables the scaling up of agroecologically produced food (Nicholls and Altieri Citation2018; Rosset et al. Citation2011; Van Der Ploeg Citation2021).

Finally, as with agroecosystem impacts, suitable tools are required to measure and understand the impacts of agroecology on the food system. For example, most participants were contributing to the development of local food systems. Recent research has highlighted that dietary shifts to more plant-based foods in affluent countries to reduce food system greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions should be accompanied by a shift to local food consumption given the significant contribution of food-miles to overall emissions (Li et al. Citation2022). It is necessary to quantify the impacts of Scottish farmers’ agroecological transitions on food-miles and their associated emissions. Additionally, it is important to recognize that GHG emissions are only one facet of environmental sustainability. As well as the environmental impacts, it is important to understand the health and wellbeing impacts of transitions to agroecology. Agroecologically produced food tends to be unprocessed or minimally processed. The recent National Food Strategy report in the UK highlighted the link between ultra-processed foods and dietary induced diseases (Dimbleby Citation2021). By engaging in food networks where such food is either absent or far less abundant, consumers may be guided to healthier eating habits. Local food networks also provide the opportunity to develop positive relationships between farmers and consumers. Not only can this have wellbeing benefits for farmers, but close contact means that consumers are informed on where their food comes from, and farmers can build consumer feedback into their production systems.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that farmers’ actualizations of agroecology in Scotland are broadly aligned with a transformative agroecological narrative (Dumont, Wartenberg, and Baret Citation2021; Rivera-Ferre Citation2018; Wezel et al. Citation2020). There is a clear value-driven dimension of participants’ approaches that aligns with a transformative vision of Scotland’s farming and food systems. Efficiency gains and cost savings were important, but not the only objectives, and were being practically implemented through a range of agroecological practices, including cover cropping, reduced tillage, livestock integration, AMP grazing, and silvopasture. Moreover, most of the farms were engaged in alternative food networks, most notably the smaller scale producers. Nevertheless, there also appear to be conceptualizations of agroecology that are linked to sustainable intensification, but lack direct social justice objectives. Great care is required in communicating this issue in farming spheres, in order not to alienate those that hold “conforming” conceptualizations of agroecology (Levidow, Pimbert, and Vanloqueren Citation2014). Farmers alone cannot bear full responsibility for agroecological transition, and it is understandable many may not look past the farm-level.

Farmers’ experiences have also revealed a mind-set associated with the sustainable farming movement, having indicated both an attitude of working with nature, and a willingness to learn (Kretschmer et al. Citation2021; Padel, Levidow, and Pearce Citation2020; Rodriguez et al. Citation2009). Farmers described working with their soils, and nature more widely, in the development of their systems. This is already a recognized mind-set within market gardening as it is at the heart of permaculture design (Whitefield Citation2004). Agroecology, however, appears to be a vehicle for bringing these ideas to a larger audience. Future work could compare this mind-set with that of conventional farmers to understand the differences more fully.

This study has been specifically interested in exploring the contribution of farmers to agroecological transition in Scotland. Nevertheless, a limitation of this research is that only the experiences of farmers have been considered. While the farm-level narrative suggests Scotland’s agroecological farmers generally hold transformative aspirations, further research ought to explore the perspective of actors across the wider food system. Secondly, based on the approaches of the study participants, involvement in alternative food networks was considered as the primary contribution to food system change. Individuals and organizations involved in Scotland’s agroecological movement may also be striving for reform of the dominant industrial food system, and further work could consider these contributions.

Finally, individuals farming on smaller scales emphasized more greatly their economic challenges. Such farms appear to be actualizing agroecology in its most transformative form. Therefore, a recommendation for policymakers is to explore the mechanisms through which smaller-scale producers can be supported in their operations. Brexit, and the ensuing reevaluation of agricultural policy perhaps presents such an opportunity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Juliette Wilson for her feedback and comments on this paper, as well as each of the farmers who participated in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aare, A. K., J. Egmose, S. Lund, and H. Hauggaard-Nielsen. 2021. Opportunities and barriers in diversified farming and the use of agroecological principles in the global north–the experiences of Danish biodynamic farmers. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (3):390–416. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1822980.

- Altieri, M. A., C. I. Nicholls, and R. Montalba. 2017. Technological approaches to sustainable agriculture at a crossroads: An agroecological perspective. Sustainability 9 (3):349. doi:10.3390/su9030349.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2):77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Carlisle, L. 2016. Factors influencing farmer adoption of soil health practices in the United States: A narrative review. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 40 (6):583–613. doi:10.1080/21683565.2016.1156596.

- Cole, L. J. H., J. P, V. Eory, A. J. Karley, C. Hawes, R. L. Walker, and C. A. Watson (2021). The Potential for an Agroecological Approach in Scotland: Policy Brief. Retrieved from

- Creswell, J. W., and D. J. Creswell. 2013. Research design : Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, 4th ed. (International student edition. ed.) Los Angeles, Calif.: Los Angeles, Calif: SAGE.

- Dale, B. 2020. Alliances for agroecology: From climate change to food system change. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (5):629–52. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1697787.

- Dimbleby, H. (2021). National Food Strategy: The Plan. Retrieved from https://www.nationalfoodstrategy.org/

- Dörfler, V., and M. Stierand. 2020. Bracketing: A phenomenological theory applied through transpersonal reflexivity. Journal of Organizational Change Management 34 (4):778–93. doi:10.1108/JOCM-12-2019-0393.

- Dumont, A. M., A. C. Wartenberg, and P. V. Baret. 2021. Bridging the gap between the agroecological ideal and its implementation into practice. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 41 (3). doi:10.1007/s13593-021-00666-3.

- Ferguson, R. S., and S. T. Lovell. 2014. Permaculture for agroecology: Design, movement, practice, and worldview. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 34 (2):251–74. doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0181-6.

- Giorgi, A. P., and B. M. Giorgi. 2003. The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design, ed. P. M. Camic, J. E. Rhodes, and L. Yardley, 243–273. Washington: American Psychological Association

- Giraldo, O. F., and P. M. Rosset. 2018. Agroecology as a territory in dispute: Between institutionality and social movements. The Journal of Peasant Studies 45 (3):545–64. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1353496.

- Gliessman, S. 2016. Transforming food systems with agroecology. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 40 (3):187–89. doi:10.1080/21683565.2015.1130765.

- Hawes, C., P. Iannetta, and G. Squire. 2021. Agroecological practices for whole-system sustainability. CAB Reviews 16 (5):1–19. doi:10.1079/PAVSNNR202116005.

- Hawes, C., M. W. Young, G. Banks, S. Begg, A. Christie, P. P. M. Iannetta, and G. R. Squire. 2019. Whole-systems analysis of environmental and economic sustainability in arable cropping systems: A case study. Agronomy 9 (8):438. doi:10.3390/agronomy9080438.

- Hill, S. B., and R. J. MacRae. 1996. Conceptual framework for the transition from conventional to sustainable agriculture. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 7 (1):81–87. doi:10.1300/J064v07n01_07.

- Kapgen, D., and L. Roudart. 2020. Proposal of a principle cum scale analytical framework for analyzing agroecological development projects. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (7):876–901. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1724582.

- Kretschmer, S., B. Langfeldt, C. Herzig, and T. Krikser. 2021. The Organic mindset: Insights from a mixed methods grounded theory (MM-GT) study into Organic food systems. Sustainability 13 (9):4724. doi:10.3390/su13094724.

- Lal, R. 2004. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Science 304 (5677):1623–27. doi:10.1126/science.1097396.

- Levidow, L., M. Pimbert, and G. Vanloqueren. 2014. Agroecological research: Conforming—or transforming the dominant agro-food regime? Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 38 (10):1127–55. doi:10.1080/21683565.2014.951459.

- Li, M., N. Jia, M. Lenzen, A. Malik, L. Wei, Y. Jin, and D. Raubenheimer. 2022. Global food-miles account for nearly 20% of total food-systems emissions. Nature Food 3 (6):445–53. doi:10.1038/s43016-022-00531-w.

- López-García, D., V. García-García, Y. Sampedro-Ortega, A. Pomar-León, G. Tendero-Acin, A. Sastre-Morató, and A. Correro-Humanes. 2020. Exploring the contradictions of scaling: Action plans for agroecological transition in metropolitan environments. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (4):467–89. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1649783.

- Lozada, L. M., and A. K. (2022). The Adoption of Agroecological Principles in Scottish Farming and Their Contribution Towards Agricultural Sustainability and Resilience. Retrieved from

- Morel, K., and F. Léger. 2016. A conceptual framework for alternative farmers’ strategic choices: The case of French organic market gardening microfarms. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 40 (5):466–92. doi:10.1080/21683565.2016.1140695.

- Murguia Gonzalez, A., O. F. Giraldo, Y. Mier, M. Terán-Giménez Cacho, and L. Rodríguez Castillo. 2020. Policy pitfalls and the attempt to institutionalize agroecology in El Salvador 2008-2018. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (8):1033–51. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1725216.

- Nicholls, C. I., and M. A. Altieri. 2018. Pathways for the amplification of agroecology. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 42 (10):1170–93. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1499578.

- Olekanma, O., V. Dörfler, and F. Shafti. 2022. Stepping into the participants’ shoes: The trans-positional cognition approach. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21:16094069211072413. doi:10.1177/16094069211072413.

- Ollivier, G., D. Magda, A. Mazé, A. S. B. E. G. Plumecocq, and C. Lamine. 2018. Agroecological transitions: What can sustainability transition frameworks teach us? An ontological and empirical analysis. Ecology and Society 23 (2):18. doi:10.5751/ES-09952-230205.

- Padel, S., L. Levidow, and B. Pearce. 2020. UK farmers’ transition pathways towards agroecological farm redesign: Evaluating explanatory models. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (2):139–63. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1631936.

- Pretty, J. N. 1994. Alternative systems of inquiry for a sustainable agriculture. IDS bulletin 25 (2):37–49. doi:10.1111/j.1759-5436.1994.mp25002004.x.

- Rivera-Ferre, M. G. 2018. The resignification process of agroecology: Competing narratives from governments, civil society and intergovernmental organizations. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 42 (6):666–85. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1437498.

- Rodriguez, J. M., J. J. Molnar, R. A. Fazio, E. Sydnor, and M. J. Lowe. 2009. Barriers to adoption of sustainable agriculture practices: Change agent perspectives. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems 24 (1):60–71. doi:10.1017/S1742170508002421.

- Rosset, P. M., B. Machín Sosa, A. M. Roque Jaime, and D. R. Ávila Lozano. 2011. The campesino-to-campesino agroecology movement of ANAP in Cuba: Social process methodology in the construction of sustainable peasant agriculture and food sovereignty. The Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (1):161–91. doi:10.1080/03066150.2010.538584.

- Schiller, K., W. Godek, L. Klerkx, and P. M. Poortvliet. 2020. Nicaragua’s agroecological transition: Transformation or reconfiguration of the agri-food regime? Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 44 (5):611–28. doi:10.1080/21683565.2019.1667939.

- Scottish Government. 2020. June Agricultural Census 2020. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2020/12/scottish-agricultural-census-final-results-june-2020/documents/scottish-agricultural-census-final-results-june-2020/scottish-agricultural-census-final-results-june-2020/govscot%3Adocument/scottish-agricultural-census-final-results-june-2020.pdf

- Scottish Government. 2021. Agricultural transition in Scotland: First steps towards our national policy. Retrived from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/consultation-paper/2021/08/agricultural-transition-scotland-first-steps-towards-national-policy-consultation-paper/documents/agricultural-transition-scotland-first-steps-towards-national-policy/agricultural-transition-scotland-first-steps-towards-national-policy/govscot%3Adocument/agricultural-transition-scotland-first-steps-towards-national-policy.pdf

- Scottish Government. 2022. Sustainable and Regenerative Farming - Next Steps: Statement. Retrieved from https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/speech-statement/2022/03/next-step-delivering-vision-scotland-leader-sustainable-regenerative-farming/documents/next-step-delivering-vision-scotland-leader-sustainable-regenerative-farming/next-step-delivering-vision-scotland-leader-sustainable-regenerative-farming/govscot%3Adocument/next-step-delivering-vision-scotland-leader-sustainable-regenerative-farming.pdf

- Shinebourne, P. 2011. The theoretical underpinnings of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA). Existential Analysis: Journal of the Society for Existential Analysis 22 (1):16–31.

- Smith, J. A., and P. Shinebourne. 2012. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In APA handbook of research methods in psychology, ed. H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, 73–82. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Tessier, L., J. Bijttebier, F. Marchand, and P. V. Baret. 2021. Pathways of action followed by Flemish beef farmers–an integrative view on agroecology as a practice. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 45 (1):111–33. doi:10.1080/21683565.2020.1755764.

- Tittonell, P. 2020. Assessing resilience and adaptability in agroecological transitions. Agricultural Systems 184:102862. doi:10.1016/j.agsy.2020.102862.

- Toffolini, Q., A. Cardona, M. Casagrande, B. Dedieu, N. Girard, and E. Ollion. 2019. Agroecology as farmers’ situated ways of acting: A conceptual framework. Agroecology & Sustainable Food Systems 43 (5):514–45. doi:10.1080/21683565.2018.1514677.

- Van Der Ploeg, J. D. 2021. The political economy of agroecology. The Journal of Peasant Studies 48 (2):274–97. doi:10.1080/03066150.2020.1725489.

- Wezel, A., B. G. Herren, R. B. Kerr, E. Barrios, A. L. R. Gonçalves, and F. Sinclair. 2020. Agroecological principles and elements and their implications for transitioning to sustainable food systems. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 40 (6):1–13. doi:10.1007/s13593-020-00646-z.

- Whitefield, P. 2004. Earth care manual: A permaculture handbook for Britain & other temperate climates. Hampshire: Permanent Publications.